Abstract

There is a critical need for translating basic science discoveries into new therapeutics for patients suffering from difficult to treat neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative conditions. Previously, a target-agnostic in vivo screen in mice identified P7C3 aminopropyl carbazole as capable of enhancing the net magnitude of postnatal neurogenesis by protecting young neurons from death. Subsequently, neuroprotective efficacy of P7C3 compounds in a broad spectrum of preclinical rodent models has also been observed. An important next step in translating this work to patients is to determine whether P7C3 compounds exhibit similar efficacy in primates. Adult male rhesus monkeys received daily oral P7C3-A20 or vehicle for 38 weeks. During weeks 2–11, monkeys received weekly injection of 5′-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) to label newborn cells, the majority of which would normally die over the following 27 weeks. BrdU+ cells were quantified using unbiased stereology. Separately in mice, the proneurogenic efficacy of P7C3-A20 was compared to that of NSI-189, a proneurogenic drug currently in clinical trials for patients with major depression. Orally-administered P7C3-A20 provided sustained plasma exposure, was well-tolerated, and elevated the survival of hippocampal BrdU+ cells in nonhuman primates without adverse central or peripheral tissue effects. In mice, NSI-189 was shown to be pro-proliferative, and P7C3-A20 elevated the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis to a greater degree than NSI-189 through its distinct mechanism of promoting neuronal survival. This pilot study provides evidence that P7C3-A20 safely protects neurons in nonhuman primates, suggesting that the neuroprotective efficacy of P7C3 compounds is likely to translate to humans as well.

Introduction

Novel therapeutics are severely lacking for patients suffering from neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases1–4. One promising avenue for central nervous system (CNS) drug development is to address alterations in the magnitude of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis and hippocampal volume reported for many CNS disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, major depression, addiction and anxiety5,6. Although questions have recently been raised regarding the extent of adult human hippocampal neurogenesis7,8, converging evidence from human and animal studies suggests that the ability to augment the net magnitude of postnatal neurogenesis may present a potential therapeutic intervention for multiple RDoC domains inclusive of symptoms associated with depressive and bipolar disorders, as well as for general conditions of impaired cognition9–15. A rigorous preclinical research pipeline is needed to translate promising pharmacological interventions identified in animal model systems into new therapeutic interventions16.

Here we present a novel, cross-species approach to advancing preclinical evaluation of the aminopropyl carbazole compound P7C3-A20 from rodents to nonhuman primates. In rodents, the P7C3-series of compounds enhances neuronal survival under conditions that would normally lead to cell death3. The prototypical P7C3 molecule was first discovered through an unbiased in vivo screen for drug-like molecules capable of safely enhancing the net magnitude of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in mice17. The third compound (C3) of the seventh pool (P7), thereby named P7C3, was discovered to have this ability by virtue of protecting young hippocampal neurons from dying, without affecting their rate of proliferation in the postnatal hippocampus. Aged rats that underwent prolonged administration of P7C3 also performed better on cognitive tasks and exhibited decreased cell death in the hippocampus17. Subsequently, the neuroprotective effects of P7C3 and its derivative compounds have been further demonstrated in broad preclinical rodent models of CNS disease and injury, including environmental stress-related hippocampal cell death18–20, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis21, Parkinson’s disease22–25, traumatic brain injury26–28, peripheral nerve crush29, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy30, optic nerve injury31,32, Alzheimer’s disease33, stroke34–36, and recently expanded to acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity37. Mechanistically, P7C3 increases nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) flux in mammalian cells under conditions of otherwise overwhelming energy crisis that would normally lead to cell death38.

While preclinical rodent models have laid the foundation for our understanding of the neuroprotective efficacy of P7C3 compounds, there are limitations in relying solely on rodent models to develop novel therapeutics for complex CNS diseases in humans39. Moreover, completion of all stages of adult hippocampal neurogenesis (i.e., proliferation, differentiation, survival, and integration) takes several weeks in rodents40, but requires months longer in both human41 and nonhuman primates42. Therefore, preclinical evaluation of drugs targeting hippocampal neurogenesis may benefit from experiments in animals more closely related to humans, such as the rhesus macaque monkey (Macaca mulatta). Rhesus monkeys are genetically and physiologically similar to humans, and are the most widely used nonhuman primate in biomedical research43. Moreover, the complex neuroanatomy and behavioral repertoire of the rhesus monkey provides a powerful preclinical platform to evaluate promising CNS therapeutic agents44,45. As an initial step in establishing a robust nonhuman primate model, we first evaluated the neuroprotective efficacy of prolonged (38 week) oral administration of P7C3-A20, one of the most highly-potent compounds in the P7C3 series20,21,23,26,35, on hippocampal neurogenesis in adult, male rhesus monkeys. Monkeys from P7C3-A20 treatment and vehicle control groups received weekly injections of the thymidine analog cell-division marker, 5′-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) during weeks 2–11 of compound exposure, followed by an extended period of 27 weeks of either P7C3-A20 or vehicle administration. In parallel, we also executed a study in mice to directly compare the proneurogenic efficacy of P7C3-A20 to that of NSI-189, a proneurogenic drug currently in clinical trials for patients with major depression. Here we present our initial findings using this integrated in vivo mouse-to-monkey evaluation of P7C3 compounds.

Materials and methods

Methods for the nonhuman primate and rodent studies are summarized briefly below and described in detail in the supplemental material.

Nonhuman primate studies

Animal selection

Experimental procedures were developed in consultation with the veterinary staff at the California National Primate Research Center and performed in accordance with the University of California, Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Eight adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: (i) Treatment with P7C3-A20 or (ii) Vehicle controls (Table 1). While this is modest sample size for a pilot study, a target sample size of N = 4 per group is not uncommon in nonhuman primate research46,47. Moreover, previous P7C3A20 data in rodent models demonstrated sufficiently low variability to achieve statistical significance with groups of this size. Unfortunately, one of the vehicle control animals was flagged by veterinary staff for health related concerns and was removed from plans for BrdU quantification resulting in a final sample of N = 4 P7C3A20 treated and N = 3 vehicle control.

Table 1.

Experimental groups

| Treatment | Age (years) | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| P7C3-A20 (N = 4) | 5.71 | 11.56 |

| Vehicle (N = 4)a | 5.98 | 11.91 |

aOne vehicle treated control was removed from BrdU quantification for unrelated medical issues, but data was included for pharmacokinetic analyses and tissue toxicity studies

P7C3-A20 formulation and treatment

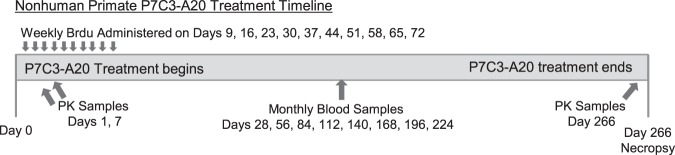

P7C3-A20 was synthesized under GLP conditions by Southwest Research Institute as further described in supplemental material. Daily oral administration of compound (10 mg/kg, 0.5 ml/kg) or vehicle control (0.5 ml/kg) was implemented at 9 am (+/−30 min) for 266 consecutive days (38 weeks) by experienced animal care technicians (Fig. 1). General health and appetite were monitored daily by trained technicians and/or veterinary staff.

Fig. 1.

Experimental timeline

BrdU injections

Each monkey received weekly injections of the thymidine analog cell-division marker, 5′-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Boehringer Mannheim, 150 mg/kg i.v.) on treatment Day 9, 16, 23, 30, 37, 44, 51, 58, 65, and 72 between 1 and 3 pm in the afternoon. The dose of BrdU was selected in order to maximize the amount of labeling, while minimizing the possible toxic side-effects of the marker48. The final BrdU injection on Day 72 occurred 194 days (27 weeks) prior to euthanasia. Previous groups have utilized an interval of 2.5 months between BrdU injection and euthanasia to allow sufficient time for nonhuman primate cells to mature49. However, more recent evidence indicates that granule cell maturation in the nonhuman primate is protracted over a minimum 6 month time period42. For this reason, we extended the time between the final BrdU injection (day 72) and euthanasia (day 266) to 6.5 months50,51.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Collection of baseline (pre-treatment) and monthly blood samples are described in supplemental materials and Fig. 1. Blood samples were processed for plasma (PK samples) or both plasma and serum (Monthly samples). CBC/CHEM panels were run on Day 0 (pre-treatment), Day 7 and at each monthly blood sample. Detection of P7C3-A20 in plasma of monkeys was conducted by Abbvie Pharmaceuticals (North Chicago, IL, USA) following a protocol previously developed for evaluation of P7C3-A20 in rodent samples)27. Compound extraction of plasma samples is further detailed in supplemental materials.

Histology and stereological analyses

Brain collection and processing from monkey followed previously established protocols52,53 and is described in further detail in supplemental material. Following perfusion, brains were extracted, placed in refrigerated paraformaldehyde, cryoprotected, and frozen in isopentane. Additional tissues, as described in supplemental materials, were collected and processed for toxicology assessment. The brain was cut into coronal sections with a freezing microtome into six 30μm series and one series at 60 μm (Microm HM 450). Every fourth section of one of the 30μm series (~15 sections evenly-spaced every 960 μm throughout the entire rostrocaudal extent of the hippocampus) was processed with BrdU immunohistochemistry. Additional sections adjacent to the BrdU immunostained sections were stained with a thionin-based Nissl protocol for anatomical reference as previously described52. An investigator blind to the treatment status of each specimen performed all analyses, as described below.

The granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in both right and left hemispheres was delineated according to previously published cytoarchitectonic descriptions54–56. Contours were drawn on each 30 μm BrdU immunostained section (evenly spaced every 960 μm throughout the entire rostrocaudal extent of the hippocampus) and verified with the nissl-stained section contours to provide a consistent boundary for counting the number of BrdU+ cells within the granule cell layer. All measurements were made using Stereoinvestigator software (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT) on a Zeiss Axio Imager.Z2 Vario microscope with automated stage controller (Ludl Mac6000) and Heidenhan length gage for z-axis (section thickness) measurement. Volume measurements were measured according to the Cavalieri principle57. The stereological method optical fractionator (counting frame: 1 µm, guard zone: 2 µm) was used to estimate the number of BrdU+ cells. BrduU+ cells were not counted if they came into focus outside of the counting frame (i.e., in the guard zone). The stereological method applied in this study adhered to the sampling scheme specifically described in West58, as follows: Given the low number of BrdU+ cells present within the counting frame, the entire area of the section for the disector was used to count all BrdU+ cells that fell within the counting frame (area sampling fraction [asf] = 1) and multiplied by the inverse of the section sampling fraction to obtain estimates of the total number of BrdU+ cells in the granule cell layer58.

Statistics

We compared mean cell counts between monkeys treated with P7C3-A20 using a two-sample t-statistic assuming unequal variances. One animal had a large cell count resulting in a skewed distribution. We therefore used a complete permutation null distribution to determine the significance level, because it does not require assuming the data were drawn from a normally-distributed population. In small samples such as represented in this study, the sample mean can be strongly impacted by very high or low values. Because of the relatively large cell counts for one animal in the intervention group, we also conducted a Wilcoxon rank sum test to compare distributions between the two groups. An exact p-value was calculated for this test. All tests were two-sided.

Rodent studies

All rodent animal procedures were performed in accordance with the University of Iowa animal care committee’s regulations. Animals were housed in temperature-controlled conditions, provided food and water ad libitum, and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (7:00 am–7:00 pm). Male C57BL/6 J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Experiments designed to compare P7C3-A20 to NSI-189 for ability to increase the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis using a standard 5 day in vivo assay were followed by targeted assays of proliferation and survival and newborn hippocampal neurons in the mouse dentate gyrus (described in supplemental material). General health and appearance of all animals was monitored daily by trained technician and veterinary staff, and no abnormalities were noted during this brief treatment period. After 5 days of daily BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) administration at 9:00 am, mouse brains were collected and prepared as described in supplemental materials. The number of BrdU+ cells in the entire dentate gyrus subgranular zone (SGZ) was quantified per our established procedures17,19,20,23,24,59. Briefly, BrdU+ cells are manually counted under 20× magnification within the SGZ and dentate gyrus in every fifth section throughout the entire hippocampus. Then a picture of the dentate gyrus field is obtained at 4X magnification, and the volume of the dentate gyrus granular cell layer is determined by using NIH Image J software tailored to the microscope to trace the area, and then multiplying by the thickness of the section. All data were normally distributed; therefore, in instances of multiple mean comparisons, analysis of variance was used, followed by post hoc comparison using Tukey’s method. In instances of direct comparison, two-tailed Student’s t-test was performed. Alpha levels were set to .05, and analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). The presence our outliers was tested using ROUT method in Prism and defined as having Q = 0.1%. In this study, no outliers were detected. Significance is denoted as *p = .05, **p = .01, ***p = .001, ****p = .0001, and not significant. A blinded examiner conducted all analyses, and code was not broken until analyses were completed.

Results

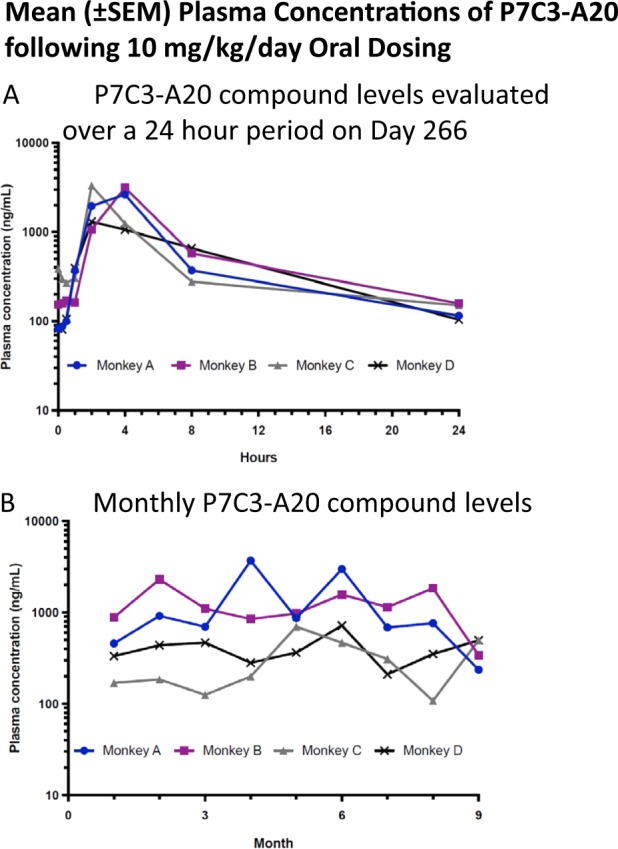

38 Weeks of daily oral dosing (10 mg/kg) of P7C3-A20 provides sustained plasma exposure in nonhuman primates

Orally-administered P7C3-A20 provided sustained plasma exposure in rhesus monkeys (Fig. 2). To ensure good compliance for compound administration, a formulation of corn oil and flavored syrup was utilized for oral dosing in the monkeys. Prior to initiation of the primate study, this formulation was evaluated in male Fisher 344 rats to ensure comparable exposures with the rodent DMSO/cremophor formulation previously utilized21,23. Exposures were found to be comparable for a 10 mg/kg dose administered by oral gavage (DMSO/Cremophor: AUC 12958 h*ng/ml, Cmax: 928 ng/ml; Oil/Syrup: AUC 15174 h*ng/ml, Cmax 1155 ng/ml). Drug levels were evaluated over a 24 h period on Day 1, 7, and 266. Overall exposure, defined as area under the curve (AUC), differed by no more than two-fold. Compound levels varied from an average Cmax of 963–2320 ng/ml at around 4 h, to a trough of 73–132 ng/ml at 24 h just prior to the next dose, as presented at day 266 (Fig. 2a). P7C3-A20 levels were also measured once a month, 6 h after dosing, a timepoint close to the estimated maximal concentration point. Here again, levels were fairly consistent and showed no trend towards increase or decrease, supporting the favorable chemical property of lack of induction or inhibition of any clearance mechanisms, such as cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism (Fig. 2b). Finally, although this represents a small cohort of animals, there was little variability between animals, indicating that consistent and fairly equivalent exposures were achieved in each non-human primate.

Fig. 2. a P7C3-A20 compound levels were evaluated over a 24 h period on Days 1, 7, and 266, and the overall exposure measured (area under the curve: AUC) differed by no more than two-fold.

Compound levels varied from an average Cmax of 963 to 2320 ng/ml at around 4 h to a trough of 73–132 ng/ml at 24 h immediately prior to the next dose. Individual animal data from day 266 are presented in a. b P7C3-A20 levels were also measured once a month, 6 h after dosing, a time point close to the estimated maximal concentration point

Chronic P7C3-A20 ingestion is not associated with toxicity in nonhuman primates

After 38 weeks of daily oral exposure at 10 mg/kg dose of P7C3-A20, tissues were comprehensively collected at necropsy and evaluated by a pathologist blind to experimental condition. No microscopic evidence of toxicology was detected in any of the tissues examined, including eyes, lung, heart, aorta, tongue, spleen, liver, kidney, adrenal, thyroid, parathyroid, pancreas, stomach, testes, small intestine, large intestine, skeletal muscle, vesicular gland, spinal cord, peripheral nerve, prostate, salivary glands, gall bladder, bone marrow, epididymis, optic nerve, lymph nodes, mammary gland, larynx, skin, trachea, ureter, bone, joint, and pituitary gland. This complete lack of toxicity after daily oral administration of P7C3-A20 for 38 weeks to non-human primates is a favorable indication for the translational potential of the P7C3-series into a safe treatment for patients.

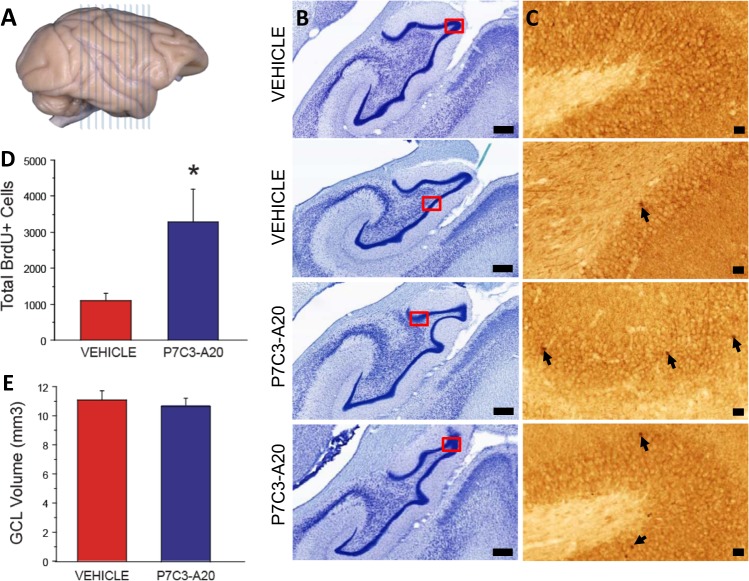

Orally-administered P7C3-A20 elevates survival of newborn hippocampal neurons in nonhuman primates: Survival of young hippocampal neurons was examined 27 weeks after the final injection of the cell-division marker BrdU (Fig. 3a–c; Table 2). The mean number of BrdU+ cells differed significantly (t = −2.30, df = 3.31, p = 0.029 based on permutation null distribution) between monkeys treated with P7C3-A20 (mean = 3275, SD = 1847) and those that received the vehicle control (mean = 1095, SD = 368) (Fig. 3d). Although the Wilcoxon test comparing the two distributions fell just short of statistical significance based on a 0.05 threshold (W = 0, p = 0.057), all treated animals had higher numbers of BrdU+ cells than animals in the control group, as shown in (Supplemental Fig. 1). Animals were randomly assigned to treatment group in order to best control for the possibility of inter-animal variation in baseline postnatal neurogenesis, and did not differ in bilateral GCL volume (p = 0.857) as a function of P7C3-A20 exposure (Fig. 3e). Although BrdU can also label DNA repair events, this is unlikely to be a factor in our study that showed a difference between P7C3-A20 and vehicle groups, as P7C3 compounds have an extensive record of safety in published preclinical models and we also saw no evidence of toxicity anywhere in the body associated with P7C3-A20 administration.

Fig. 3. a Approximately 15 sections per animal evenly spaced 960 μm apart covering the rostral to caudal extent of the hippocampus were used to estimate the number of BrdU-labeled cells.

b Contours were outlined on Nissl-stained sections for anatomical reference. c Contours were drawn on BrdU immunohistochemically stained sections to measure volume and count the number of BrdU-labeled cells within the granule cell layer. d The total number of BrdU positive cells (left and right hemispheres) differed significantly (p = 0.029) between monkeys treated with P7C3A20 (mean = 3275, SD = 1847) and those that received the vehicle control (mean = 1095, SD = 368). However, median values fell just shy of the set significance value at 0.05 level (p = 0.056). e As predicted, the groups did not differ in bilateral GCL volume (p = 0.857) as a function of P7C3-A20 exposure

Table 2.

Summary of average number BrdU positive cell counts and GCL volumes [Mean (±SEM)]

| BrdU positive cells | GCL volume (mm³) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left hemisphere | Right hemisphere | Left hemisphere | Right hemisphere | |

| Vehicle | 597 (±115) | 498 (±116) | 10.7 (±0.2) | 11.4 (±1.3) |

| P7C3-A20 treated | 1495 (±514) | 1781 (±409) | 10.1 (±0.8) | 11.3 (±0.5) |

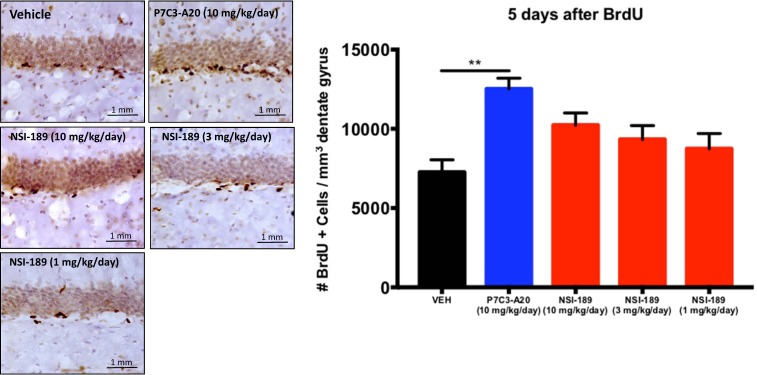

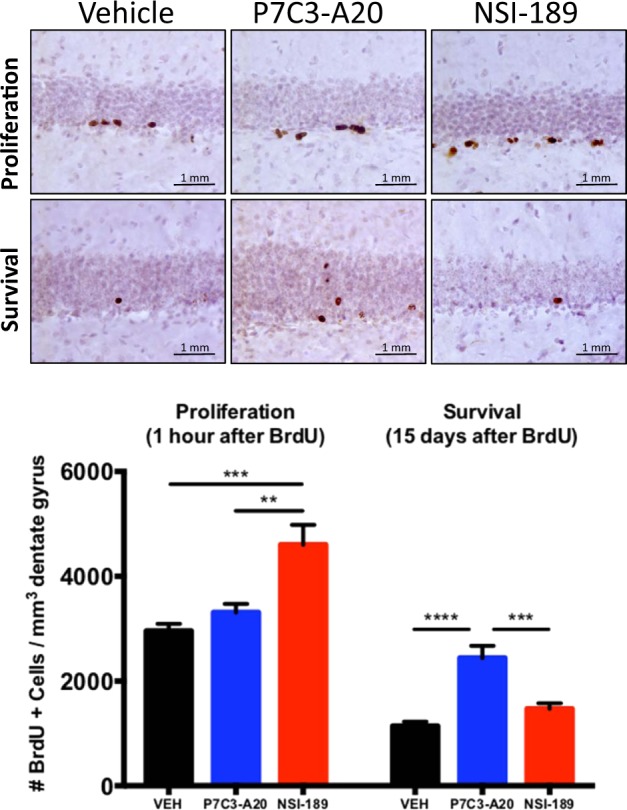

P7C3-A20 is more efficacious and mechanistically distinct in mice from the proneurogenic drug NSI-189

We next compared in mice the efficacy of P7C3-A20 to that of NSI-189, an experimental proneurogenic drug that acts by unknown mechanisms to enhance hippocampal neurogenesis. To date, NSI-189 has shown protective efficacy in a rat model of stroke60, as well as a promising effect in a phase1B randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled multiple dose-escalation study in adult patients with major depressive disorder61. We first compared P7C3-A20 to NSI-189 for the ability to increase the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis in a standard 5 day in vivo assay of BrdU-labeled cells in the dentate gyrus17. Here, mice were socially isolated without any environmental enrichment for 2 weeks, per our standard protocol, and then subjected to daily administration of both the test proneurogenic compound and a daily dose of BrdU (50 mg/kg ip). In this experiment, NSI-189 showed a nonsignificant dose-dependent increase in the number of BrdU + cells, whereas P7C3-A20 showed a statistically significant (p < .01) increase in the number of BrdU+ cells compared to vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Compounds were administered intraperitoneally at the daily dose indicated for 5 days, during which time mice were also dosed intraperitoneally daily with BrdU (50 mg kg-1day-1) to label newborn hippocampal neurons.

Representative micrographs are shown on the left, with quantified data on the right represented as mean +/- standard error of the mean (SEM). NSI-189-treated mice showed a nonsignificant increase in the number of BrdU+ cells that was statistically not different from vehicle. P7C3-A20-treated mice showed a statistically significant (p < .01) increase in the number of BrdU+ cells compared to vehicle-treated animals

The standard 5 day assay captures agents that increase the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis, without distinguishing whether they act by enhancing proliferation or promoting survival. For example, this assay was originally used to discover the prototypical P7C3 molecule17, which was subsequently shown to elevate hippocampal neurogenesis by selectively blocking neuronal death with affecting proliferation of neural precursor cells. Thus, we compared P7C3-A20 to NSI-189 in standard assays of proliferation (1 h after BrdU administration) and survival (15 days after BrdU administration) (Fig. 5). Proliferation was assayed by measuring the number of BrdU+ cells/mm3 dentate gyrus 1 h after a pulse of BrdU (150 mg/kg ip) in animals that had already received 3 days of daily P7C3-A20 (10 mg/kg/day ip) or NSI-189 (10 mg/kg/day ip). Here, P7C3-A20 elicited no increase in cellular proliferation, compatible with our previous observations, while treatment with NSI-189 elevated proliferation of neural precursor cells by approximately 70%. Next, to assay the neuroprotective efficacy for young hippocampal neurons, we measured the number of BrdU+ cells/mm3 dentate gyrus 15 days after a pulse of BrdU (150 mg/kg ip) in animals that received daily treatment with either P7C3-A20 (10 mg/kg/day ip) or NSI-189 (10 mg/kg/day ip) starting at the time of delivery of the BrdU pulse. Here, animals treated with P7C3-A20 showed a survival rate approximately three times greater than vehicle-treated animals, with migration of some cells out of the subgranular zone and into the dentate gyrus (Fig. 5). Animals treated with NSI-189, however, showed only a minor and non-significant trend towards increased survival, indicating that the proneurogenic efficacy of NSI-189 is likely confined to its pro-proliferative cellular effect. These experiments show that P7C3 compounds increase the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis to a greater extent than NSI-189 by virtue of the ability of P7C3 compounds to protect neurons from cell death.

Fig. 5. Efficacy on enhancing proliferation of hippocampal neural precursor cells and survival of young hippocampal neurons was compared between NSI-189 and P7C3-A20 at a dose of 10 mg kg−1day−1 administered intraperitoneally.

Representative micrographs of BrdU+ cells in the dentate gyrus are shown above, with quantified data displayed below as mean +/- standard error of the mean (SEM). Proliferation was assayed in animals that had received 3 days of daily P7C3-A20 or NSI-189, followed by a 1 h pulse of of BrdU (150 mg/kg ip) P7C3-A20 elicited no increase in cellular proliferation compared to the level seen in vehicle-treated animals. NSI-189 elevated proliferation of neural precursor cells by approximately 70% relative to vehicle (p < .001) and P7C3-A20-treated mice (p < 0.01). Neuroprotective efficacy for young hippocampal neurons was assayed in animals that received the same pulse of BrdU at the same time as initiation of 15 days of daily treatment with P7C3-A20 or NSI-189. P7C3-A20-treated animals showed a survival rate approximately three times greater than vehicle-treated (p < .0001) and NSI-189-treated (p < .001) animals, with migration of some cells out of the subgranular zone and into the dentate gyrus. Animals treated with NSI-189 showed a minor and non-significant trend towards increased survival, indicating that the proneurogenic efficacy of NSI-189 is likely confined to its pro-proliferative effect on cells. P7C3 compounds increase the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis to a greater extent than NSI-189 by virtue of the unique ability of P7C3 compounds to protect neurons from cell death

Discussion

P7C3 compounds were first identified through an unbiased screen of hippocampal neurogenesis in rodents17, and subsequently shown to have neuroprotective properties for a number of CNS relevant rodent models18–35. Here we establish the next step in advancing P7C3 along the translational pipeline into a species more closely related to humans—the rhesus macaque. This study provides two major, novel findings. First, we demonstrate that orally-administered P7C3-A20 provides sustained plasma exposure, is well-tolerated, and protects young hippocampal neurons in the adult male rhesus macaque. A higher number of BrdU+ cells in the dentate gyrus were detected in monkeys treated daily with P7C3-A20 compared to vehicle (Fig. 3). Second, in a direct comparison in mice treated with P7C3-A20 compared to the drug NSI-189 that is currently in clinical trials for patients with major depression, the survival-promoting effect of P7C3-A20 appears to augment the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis more effectively than the pro-proliferative effect of NSI-189 (Figs. 4, 5). The present studies add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that P7C3 compounds offer a promising therapeutic intervention for a number of CNS disorders. Mechanistically, we have shown in rodent models an cellular systems that P7C3 increases neuronal NAD flux under conditions that would normally lead to cell death38, and efficacy of P7C3 compounds in the nonhuman primate suggests that this general mechanisms of neuronal protection is likely to be operational in humans as well.

Our initial efforts in the nonhuman primate model focus on the neuroprotective properties of P7C3 compounds related to adult neurogenesis in the primate hippocampus. As first described in rodents62, neurons born in the subgranular zone (SGZ) migrate and integrate into the granule cell layer50,51,63, a process that takes months longer in nonhuman primates42 and humans41 than in rodents. Hippocampal neurogenesis peaks at 3 months of age for macaques and remains at an intermediate level between 3 months and at least 1 year of age (roughly equivalent to early childhood)49. Adult macaques and humans demonstrate persistent levels of neurogenesis in adulthood49,64, though the number of surviving newborn neurons decreases substantially with age65. Studies from rodent models indicate that adult-born neurons demonstrate a transient period of excitability and plasticity thought to recapitulate the early stages of fetal and postnatal brain development66,67. These properties suggest that adult-born cells may be uniquely positioned to impact hippocampal activity, in spite of their relatively low abundance40. Thus, adult-born neurons are thought to enhance function of hippocampal networks68,69, though there is no consensus on exact functional contributions. Although new neurons are generated in the adult human dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus8,63, the extent to which human hippocampal neurogenesis persists in aging has been debated7. While additional research in this fascinating field is clearly warranted, we also stress that P7C3 compounds are proneurogenic by virtue of the fact that their neuroprotective efficacy encompasses both mature and newborn neurons. A compound that protects against neuronal loss is potentially more attractive for clinical development than one that exclusively targets proliferation of newborn neurons in the brain, as a broad and critical role of neuronal loss has been firmly established in a wide variety of neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions.

Dysregulated hippocampal neurogenesis has been linked to a number of neuropsychiatric diseases, including major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and anxiety70–76. The ability to regulate adult hippocampal neurogenesis may thus provide a route to develop novel treatments for human neuropsychiatric disease77, as evidenced by the links between behavioral effects of antidepressants and stimulation of hippocampal neurogenesis in preclinical78,79 and clinical studies80–82. The current findings support further investigation of the neuroprotective effects of P7C3 compounds in nonhuman primate models of impaired cognition83–85 or stress-related behaviors86,87. P7C3 compounds have also demonstrated neuroprotective properties in rodent models of nervous system disease and injury that involve neurodegeneration outside of the hippocampus (i.e., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, stroke, and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy). Given that nonhuman primate models exist for these disorders, we are now positioned to explore the therapeutic potential of the P7C3 class of molecules in sophisticated nonhuman primate disease models. In future studies with larger number of animals we will also incorporate analysis of brain levels of P7C3 compounds as well, in addition to blood. This integrated in vivo mouse-to-monkey evaluation of neuroprotective compounds may provide important benchmarks for utilizing cross-species animal models and accelerate drug discovery efforts.

In order to assess the survival-promoting effect of P7C3-A20 relative to the drug NSI-189 currently in clinical trials for major depression, we also carried out a direct comparison in mice and found that P7C3-A20 augmented the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis more effectively than NSI-189. That NSI-189 promoted proliferation but failed to show a sustained increase in net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis 15 days later suggests that a brief increase in proliferation does not elicit sustained improvement in hippocampal function. However, it is unknown whether prolonged chronic administration of NSI-189 might eventually achieve this objective through chronic elevation of the rate of proliferation of hippocampal neural precursor cells. We have previously shown that P7C3-A20 exerts potent antidepressant efficacy in a rodent model of chronic social defeat stress20 in a manner specifically linked to its ability to increase the net magnitude of hippocampal neurogenesis by virtue of its survival-promoting mode of action, and NSI-189 has shown promising results in a phase1B randomized double-blinded placebo controlled multiple dose-escalation study in adults with major depressive disorder61. Inasmuch as augmenting hippocampal neurogenesis can be assumed to represent a novel route to treating patients with depression76,88, our results of greater potency and efficacy of P7C3 compounds suggest that a drug to emerge from the P7C3 class of neuroprotective molecules might have superior efficacy to NSI-189. In addition, concurrent administration of P7C3 compounds and pro-proliferative compounds like NSI-189 might have a synergistic effect in enhancing hippocampal neurogenesis and treating depression or hippocampal-related cognitive dysfunction in patients suffering from a spectrum of neurodegenerative conditions related to injury, disease, or normal aging.

Collectively, these studies suggest that the neuroprotective property of P7C3 compounds may have broad applicability for a number of human CNS disorders. The primary limitation of the current study is the small sample size of adult nonhuman primates. However, small sample sizes are not uncommon for initial pilot studies in nonhuman primates46,47. Given that early translational studies tend to have quite high per-subject costs, initial nonhuman primate studies must balance the potential information gained versus ethical and financial factors89. Moreover, the current nonhuman primate study included only male subjects. In rodent preclinical models of disease in which P7C3 compounds have been previously applied, efficacy has correlated with incorporation of surviving and mature neurons into appropriate circuitry of the brain related to behavioral outcome in both males and females. Despite these limitations, this initial nonhuman primate study has generated preliminary data that support further evaluation of P7C3-A20 compounds as a promising treatment for human CNS diseases. In future studies, we will seek to replicate the nonhuman primate findings in a larger sample and also determine whether P7C3 compounds have efficacy in female nonhuman primates. We will also explore hippocampal asymmetry, given that right and left hippocampal volumes differ in the healthy human brain90,91 and in CNS diseases92,93. In addition, we will pursue more sophisticated physiologic analysis of neuronal survival and incorporation into brain circuitry related to behavioral outcome measures, such as cognitive and mood-like behaviors, and explore the therapeutic potential of the P7C3 class of molecules in sophisticated nonhuman primate disease models. The ultimate goal is to translate basic science into new therapeutic approaches for patients suffering from neuropsychiatric or neurodegenerative conditions for which there are currently sub-optimal or no treatment options.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIMH R21 NS081487 to M.D.B. and A.A.P, the CNPRC base grant OD011107, funds from The Hartwell Foundation to A.A.P., funds from an anonymous donor to the Mary Alice Smith Fund for Neuropsychiatry Research to A.A.P, and funds from the Brockman Medical Research Foundation. Pathological analysis of tissue conducted by Abbvie Pharmaceuticals (North Chicago, Illinois, USA) was funded by Calico LLC (California Life Company). Special acknowledgements are due to Research Services and Primate Medicine staff at the California National Primate Research Center for care of the animals and in particular to T. Traill for her assistance with compound administration and to Dr. David Amaral for consultation on experimental design and use of microscopy equipment. Data analysis was supported by the NIH-funded MIND Institute Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (U54 HD079125). We would like to thank Katherine Ku for her assistance in GCL volumetric data collection, Alicja Omanska for assistance with tissue processing and Casey Hogrefe for assistance with manuscript preparation. Finally, we thank Dr. Karl Murray for insightful comments on an early draft of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

AAP is a founder of a privately-held company involved in development of the subject matter. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Melissa D. Bauman, Phone: +(916) 703-0377, Email: mdbauman@ucdavis.edu

Andrew A. Pieper, Phone: +(216) 368-4273, Email: Andrew.Pieper@HarringtonDiscovery.org

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-018-0244-1).

References

- 1.Kesselheim AS, Hwang TJ, Franklin JM. Two decades of new drug development for central nervous system disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:815–816. doi: 10.1038/nrd4793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gribkoff VK, Kaczmarek LK. The need for new approaches in CNS drug discovery: why drugs have failed, and what can be done to improve outcomes. Neuropharmacology. 2017;120:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pieper AA, McKnight SL, Ready JM. P7C3 and an unbiased approach to drug discovery for neurodegenerative diseases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:6716–6726. doi: 10.1039/C3CS60448A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pieper AA, Baraban JM. Moving beyond serendipity to mechanism-driven psychiatric therapeutics. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:533–536. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0547-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoenfeld TJ, Cameron HA. Adult neurogenesis and mental illness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:113–128. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenfeld TJ, et al. Stress and loss of adult neurogenesis differentially reduce hippocampal volume. Biol. Psychiatry. 2017;82:914–923. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorrells SF, et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature. 2018;555:377–381. doi: 10.1038/nature25975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boldrini M, et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis persists throughout aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22:589–599 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAvoy KM, Sahay A. Targeting adult neurogenesis to optimize hippocampal circuits in aging. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:630–645. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0539-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serafini G, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis, neurotrophic factors and depression: possible therapeutic targets? CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2014;13:1708–1721. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666141130223723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahay A, Hen R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/nn1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McIntyre RS, et al. The neurogenic compound, NSI-189 phosphate: a novel multi-domain treatment capable of pro-cognitive and antidepressant effects. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2017;26:767–770. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1324847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder JS, et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis buffers stress responses and depressive behaviour. Nature. 2011;476:458–461. doi: 10.1038/nature10287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glover LR, et al. Ongoing neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus mediates behavioral responses to ambiguous threat cues. PLoS Biol. 2017;15:e2001154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameron HA, Glover LR. Adult neurogenesis: beyond learning and memory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015;66:53–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goetghebeur PJ, Swartz JE. True alignment of preclinical and clinical research to enhance success in CNS drug development: a review of the current evidence. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:586–594. doi: 10.1177/0269881116645269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pieper AA, et al. Discovery of a proneurogenic, neuroprotective chemical. Cell. 2010;142:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Jesus-Cortes H, Rajadhyaksha AM, Pieper AA. Neurogenesis. 2016. Cacna1c: protecting young hippocampal neurons in the adult brain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee AS, De Jesús-Cortés H, Kabir ZD, Knobbe W, Orr M, Burgdorf C, Huntington P, McDaniel L, Britt JK, Hoffmann F, Brat DJ, Rajadhyaksha AM, Pieper AA. The Neuropsychiatric Disease-Associated Gene cacna1c Mediates Survival of Young Hippocampal Neuron. eNeuro. 2016;3:27066530. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0006-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker AK, et al. The P7C3 class of neuroprotective compounds exerts antidepressant efficacy in mice by increasing hippocampal neurogenesis. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015;20:500–508. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tesla R, et al. Neuroprotective efficacy of aminopropyl carbazoles in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17016–17021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213960109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Jesus-Cortes H, et al. Protective efficacy of P7C3-S243 in the 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 2015;1:15010. doi: 10.1038/npjparkd.2015.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Jesus-Cortes H, et al. Neuroprotective efficacy of aminopropyl carbazoles in a mouse model of Parkinson disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17010–17015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213956109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naidoo J, et al. Discovery of a neuroprotective chemical, (S)-N-(3-(3,6-dibromo-9H-carbazol-9-yl)-2-fluoropropyl)-6-methoxypyridin-2-amine [(-)-P7C3-S243], with improved druglike properties. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:3746–3754. doi: 10.1021/jm401919s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu C, et al. P7C3 inhibits GSK3beta activation to protect dopaminergic neurons against neurotoxin-induced cell death in vitro and in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2858. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blaya MO, et al. Neuroprotective efficacy of a proneurogenic compound after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2014;31:476–486. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin TC, et al. P7C3 neuroprotective chemicals block axonal degeneration and preserve function after traumatic brain injury. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1731–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dutca LM, et al. Early detection of subclinical visual damage after blast-mediated TBI enables prevention of chronic visual deficit by treatment with P7C3-S243. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014;55:8330–8341. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kemp SW, et al. Pharmacologic rescue of motor and sensory function by the neuroprotective compound P7C3 following neonatal nerve injury. Neuroscience. 2015;284:202–216. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LoCoco PM, et al. Pharmacological augmentation of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) protects against paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. eLife. 2017;6:e29626. doi: 10.7554/eLife.29626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oku H, et al. P7C3 suppresses neuroinflammation and protects retinal ganglion cells of rats from optic nerve crush. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017;58:4877–4888. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-22179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oku H, et al. Protective effect of P7C3 on retinal ganglion cells from optic nerve injury. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 2017;61:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s10384-016-0493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voorhees Jaymie R., Remy Matthew T., Cintrón-Pérez Coral J., El Rassi Eli, Khan Michael Z., Dutca Laura M., Yin Terry C., McDaniel Latisha N., Williams Noelle S., Brat Daniel J., Pieper Andrew A. (−)-P7C3-S243 Protects a Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease From Neuropsychiatric Deficits and Neurodegeneration Without Altering Amyloid Deposition or Reactive Glia. Biological Psychiatry. 2018;84(7):488–498. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang SN, et al. Neuroprotective efficacy of an aminopropyl carbazole derivative P7C3-A20 in ischemic stroke. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2016;22:782–788. doi: 10.1111/cns.12576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loris ZB, Pieper AA, Dalton Dietrich W. The neuroprotective compound P7C3-A20 promotes neurogenesis and improves cognitive function after ischemic stroke. Exp. Neurol. 2017;290:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loris ZB, et al. Beneficial effects of delayed P7C3-A20 treatment after transient MCAO in rats. Transl. Stroke Res. 2017;9:146–156. doi: 10.1007/s12975-017-0565-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang LQ, et al. Novel protective role of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase in acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2018;188:1640–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang G, et al. P7C3 neuroprotective chemicals function by activating the rate-limiting enzyme in NAD salvage. Cell. 2014;158:1324–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/nn.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goncalves JT, Schafer ST, Gage FH. Adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus: from stem cells to behavior. Cell. 2016;167:897–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bergmann O, Spalding KL, Frisen J. Adult neurogenesis in humans. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015;7:a018994. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohler SJ, et al. Maturation time of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus of adult macaque monkeys exceeds six months. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:10326–10331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017099108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhesus Macaque Genome S, et al. Evolutionary and biomedical insights from the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316:222–234. doi: 10.1126/science.1139247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips KA, et al. Why primate models matter. Am. J. Primatol. 2014;76:801–827. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson KK, Platt ML. Of mice and monkeys: using non-human primate models to bridge mouse- and human-based investigations of autism spectrum disorders. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2012;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenzweig ES, et al. Extensive spontaneous plasticity of corticospinal projections after primate spinal cord injury. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:1505–1510. doi: 10.1038/nn.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenzweig ES, et al. Restorative effects of human neural stem cell grafts on the primate spinal cord. Nat. Med. 2018;24:484–490. doi: 10.1038/nm.4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cameron HA, McKay RD. Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;435:406–417. doi: 10.1002/cne.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jabes A, et al. Quantitative analysis of postnatal neurogenesis and neuron number in the macaque monkey dentate gyrus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;31:273–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gould E, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis in adult Old World primates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5263–5267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kornack DR, Rakic P. Continuation of neurogenesis in the hippocampus of the adult macaque monkey. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5768–5773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lavenex P, et al. Postmortem changes in the neuroanatomical characteristics of the primate brain: hippocampal formation. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009;512:27–51. doi: 10.1002/cne.21906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bauman MD, Amaral DG. The distribution of serotonergic fibers in the macaque monkey amygdala: an immunohistochemical study using antisera to 5-hydroxytryptamine. Neuroscience. 2005;136:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amaral DG, Scharfman HE, Lavenex P. The dentate gyrus: fundamental neuroanatomical organization (dentate gyrus for dummies) Prog. Brain Res. 2007;163:3–22. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jabes A, et al. Postnatal development of the hippocampal formation: a stereological study in macaque monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol. 2011;519:1051–1070. doi: 10.1002/cne.22549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lavenex P, Amaral DG. Hippocampal-neocortical interaction: a hierarchy of associativity. Hippocampus. 2000;10:420–430. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<420::AID-HIPO8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.West MJ, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the number of neurons in the human hippocampus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990;296:1–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.West MJ. Basic Stereology for Biologists and Neuroscientists. , New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacMillan KS, et al. Development of proneurogenic, neuroprotective small molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1428–1437. doi: 10.1021/ja108211m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tajiri N, et al. NSI-189, a small molecule with neurogenic properties, exerts behavioral, and neurostructural benefits in stroke rats. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017;232:2731–2740. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fava M, et al. A Phase 1B, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, multiple-dose escalation study of NSI-189 phosphate, a neurogenic compound, in depressed patients. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:1483–1484. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Altman J, Das GD. Post-natal origin of microneurones in the rat brain. Nature. 1965;207:953–956. doi: 10.1038/207953a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eriksson PS, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spalding KL, et al. Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell. 2013;153:1219–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galvan V, Jin K. Neurogenesis in the aging brain. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2007;2:605–610. doi: 10.2147/cia.s1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Laplagne DA, et al. Functional convergence of neurons generated in the developing and adult hippocampus. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Esposito MS, et al. Neuronal differentiation in the adult hippocampus recapitulates embryonic development. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:10074–10086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3114-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schinder AF, Gage FH. A hypothesis about the role of adult neurogenesis in hippocampal function. Physiology. 2004;19:253–261. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00012.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Piatti VC, Ewell LA, Leutgeb JK. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus: carrying the message or dictating the tone. Front. Neurosci. 2013;7:50. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reif A, et al. Neural stem cell proliferation is decreased in schizophrenia, but not in depression. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:514–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lucassen PJ, et al. Decreased numbers of progenitor cells but no response to antidepressant drugs in the hippocampus of elderly depressed patients. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:940–949. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Allen KM, Fung SJ, Weickert CS. Cell proliferation is reduced in the hippocampus in schizophrenia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2016;50:473–480. doi: 10.1177/0004867415589793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walton NM, et al. Detection of an immature dentate gyrus feature in human schizophrenia/bipolar patients. Transl. Psychiatry. 2012;2:e135. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sahay A, et al. Increasing adult hippocampal neurogenesis is sufficient to improve pattern separation. Nature. 2011;472:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature09817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Terrillion CE, et al. DISC1 in astrocytes influences adult neurogenesis and hippocampus-dependent behaviors in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:2242–2251. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hill AS, Sahay A, Hen R. Increasing adult hippocampal neurogenesis is sufficient to reduce anxiety and depression-like behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:2368–2378. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yun S, et al. Re-evaluating the link between neuropsychiatric disorders and dysregulated adult neurogenesis. Nat. Med. 2016;22:1239–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm.4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Santarelli L, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301:805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Perera TD, et al. Necessity of hippocampal neurogenesis for the therapeutic action of antidepressants in adult nonhuman primates. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boldrini M, et al. Hippocampal angiogenesis and progenitor cell proliferation are increased with antidepressant use in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;72:562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Boldrini M, et al. Hippocampal granule neuron number and dentate gyrus volume in antidepressant-treated and untreated major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1068–1077. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boldrini M, et al. Antidepressants increase neural progenitor cells in the human hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2376–2389. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burke SN, Ryan L, Barnes CA. Characterizing cognitive aging of recognition memory and related processes in animal models and in humans. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2012;4:15. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2012.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Engle JR, Barnes CA. Characterizing cognitive aging of associative memory in animal models. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2012;4:10. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2012.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gray DT, Barnes CA. Distinguishing adaptive plasticity from vulnerability in the aging hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2015;309:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Coe CL, et al. Prenatal stress diminishes neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of juvenile rhesus monkeys. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;54:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00698-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gould E, et al. Proliferation of granule cell precursors in the dentate gyrus of adult monkeys is diminished by stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:3168–3171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yun S, et al. Stimulation of entorhinal cortex-dentate gyrus circuitry is antidepressive. Nat. Med. 2018;24:658–666. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bacchetti P, Deeks SG, McCune JM. Breaking free of sample size dogma to perform innovative translational research. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:87ps24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pedraza O, Bowers D, Gilmore R. Asymmetry of the hippocampus and amygdala in MRI volumetric measurements of normal adults. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2004;10:664–678. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704105080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Woolard AA, Heckers S. Anatomical and functional correlates of human hippocampal volume asymmetry. Psychiatry Res. 2012;201:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kronmuller KT, et al. Hippocampal volume in first episode and recurrent depression. Psychiatry Res. 2009;174:62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Walter A, et al. Hippocampal volume in subjects at clinical high-risk for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016;71:680–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.