Abstract

River biofilms dominated by Phormidium (cyanobacteria) are receiving increased attention worldwide because of a recent expansion in their distribution and their ability to produce neurotoxins leading to animal mortalities. Limited data are available on the composition and structure of bacterial communities (BCs) associated with Phormidium biofilms despite the important role they potentially play in biofilm functioning. By using a high-throughput sequencing approach, we compared the BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms in several sampling sites of the Tarn River (France) and in eight New Zealand rivers. The structure of the BCs from both countries displayed spatial and temporal variations but were well conserved at the order level and 28% of the OTUs containing 90% of the reads were shared by these BCs. This suggests that micro-environmental conditions occurring within thick Phormidium biofilms strongly shape the associated BCs. A strong and significant distance-decay relationship (rp = 0.7; P = 0.001) was found in BCs from New Zealand rivers but the Bray-Curtis dissimilarities between French and New Zealand BCs are in the same order of magnitude of those found between New Zealand BCs. All these findings suggest that local environmental conditions seem to have more impact on BCs than dispersal capacities of bacteria.

Introduction

In order to better understand the causes of cyanobacterial blooms in freshwater ecosystems, numerous studies have investigated the potential relationships between heterotrophic bacteria and cyanobacteria. Based on field studies1 or cyanobacterial cultures2,3 it has been shown that bacterial communities (BCs) display dramatic changes in their structure during the development of cyanobacterial blooms. The BCs associated with the biofilm-forming benthic cyanobacteria Phormidium have also been shown to undergo successional changes during their development4. These data suggest that the development of cyanobacterial blooms may exerts strong direct and indirect influences on BCs through their modification of chemical parameters of the water (e.g., pH and oxygen concentrations) and on the availability of organic matter that is generated by their proliferation.

There is limited data available on the putative existence of spatial patterns in planktonic or benthic BCs. Studies that have investigated the paradigm “everything is everywhere, but, the environment selects” proposed by Baas-Becking and Beijerink5, have been performed on microbial communities with the goal of improving knowledge on the relative impact of species sorting (i.e., species are selected by environmental filtering6), and of dispersal limitation (i.e., micro-organisms can show dispersal limitation either if their movement to a new location is restricted or if establishment of individuals in a new location is hindered)7 on BC biodiversity8–10. These processes may lead to the differentiation of spatial patterns of biodiversity into communities. Among these processes the most studied to date is the distance-decay relationship in which similarity between biological communities decreases with increasing geographic distance11.

Several studies have already explored microbial communities living in stream biofilms revealing a lower diversity compared to suspended stream water communities12,13 and that stream biofilm communities were more influenced by environmental factors14 or catchment land use attributes13 than by dispersal limitation. Moreover, it was shown by Heino et al.15 that in microbial communities from boreal streams, local environmental conditions were the main drivers of variations; nevertheless, much of these variations remained unexplained. Recently, Peipoch et al.16 also found that BCs from epilithic biofilms in river-floodplain systems displayed spatial variations that were mainly explained by a concomitance of local and regional effects. Interestingly, a distance-decay relationship was also found between BC from epilithic biofilms, this relationship seeming to be linked to regional-scale differences in environmental conditions rather than to a real influence of the geographic distance associated to dispersal limitations.

All these studies provided interesting insights on the question of the processes driving the diversity and the spatial variations occurring in BCs living in association with photosynthetic microorganisms in biofilms but many questions still remain. Among them, the influence of the dominant photosynthetic microbial species into stream biofilms has not been taken into account. Biofilms dominated by diatoms, green algae and cyanobacteria display important differences in their characteristics (i.e., biomass, thickness) and consequently on the habitat provided to the associated BCs.

The aim of our study was to investigate, across various temporal and spatial scales, the variations occurring in the structure of BCs specifically associated with river biofilms dominated by Phormidium (cyanobacteria) (hereafter referred as Phormidium biofilms). Temporal analyses were performed by studying the BC’s changes occurring at intra seasonal to inter annual scales in the Tarn River (France). The spatial analyses were performed at scales, from the local (intra-river, Tarn River) up to the regional (inter-river in New Zealand) and global (inter-country, comparison France and New Zealand) levels. All the Phormidium biofilms were sampled during the summer season and the BCs were characterized using a 16S rRNA meta-barcoding approach.

Results

Environmental and biological parameters

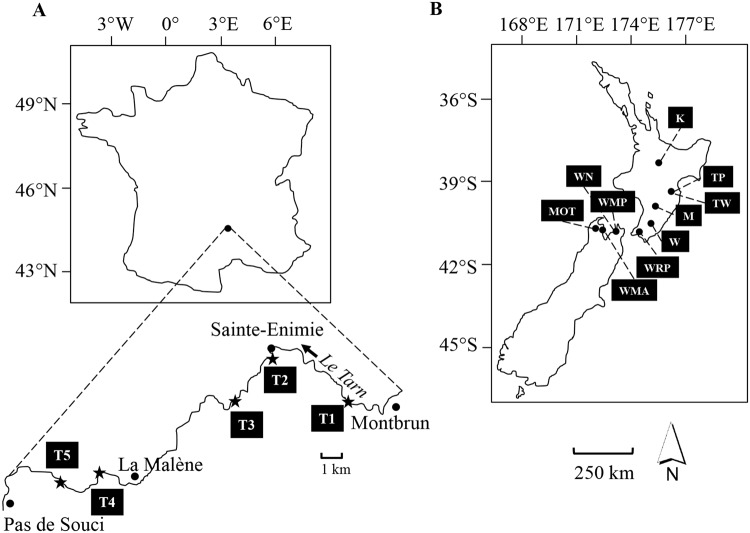

Flow velocities at which biofilms were collected in the sampling sites in the Tarn River (see Fig. 1A) ranged between 0.2 ± 0.2 to 0.6 ± 0.2 m s−1 (lowest and highest averages by site ± SD; Supplementary Table S1). New Zealand rivers (See Fig. 1B) were within the same range (Supplementary Table S2), except for site MOT (Motueka River) where higher flow velocities were registered (i.e. 1.1 ± 0.1 m s−1). Overall, Phormidium biofilms developed at shallow depths (36 and 18.4 cm on average in the Tarn and New Zealand rivers respectively), with river water pH values close to 8.0 and temperatures above 14 °C. Biofilm biomasses (expressed in terms of Chl-a concentration) were very similar among the rivers, however the highest biomasses were detected in August and September (up to 30.2 ± 10.1 μg cm−2) in the Tarn River and in site Waipoua River (40.7 ± 8.3 μg cm−2) in New Zealand. Average values of Phormidium coverage at the bottom of the rivers were very similar (22.5 and 20.5% on average in the Tarn and New Zealand rivers respectively).

Figure 1.

Sample sites located in France at Tarn River (A) sites T1: 44°20′23.08″N/3°28′2.43″E, T2 (Sainte-Enimie): 44°21′47.47″N/3°24′43.58″E, T3: 44°20′26.39″N/3°23′12.66″E, T4: 44°18′17.60″N/3°17′53.03″E and T5: 44°17′53.44″N/3°16′48.21″E) and in New Zealand (B) on the North Island, sites K: 38°53′19.10″S/175°46′7.54″E at Kuratau River, TP: 39°54′38.24″S/176°43′45.61″E and TW: 39°59′24.23″S/176°33′33.08″E at Tukituki River, M: 40°24′50.60″S/175°52′14.59″E at Mangatainoka River, W: 40°56′34.10″S/175°39′49.60″E at Waipoua River, WRP: 41°16′20.42″S/174°57′50.08″E at Wainuiomata River, on the South Island WN: 41°12′58.68″S/173°23′44.35″E and WMP: 41°11′13.03″S/173°25′19.24″E at Wakapuaka River, MOT: 41°15′40.25″S/172°49′16.17″E at Motueka River, WMA: 41°18′42.37″S/173°7′41.69″E at Waimea River. Countries are to scale.

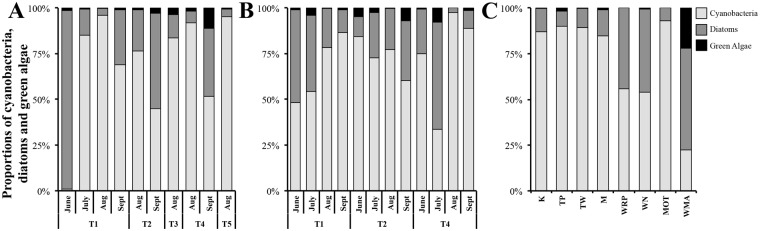

Spatio-temporal variations in the structure of biofilm photosynthetic communities

Microscopic analysis demonstrated that the biofilms were dominated by cyanobacteria (79.2% ± 19.2; predominantly Phormidium sp. Tarn 2013: 97.4% ± 13.0; Tarn 2014: 99.8% ± 0.7; New Zealand 2013: 94.6% ± 20.5), followed by diatoms (19.0% ± 18.1) and green algae (1.8% ± 3.6) (Fig. 2). This pattern was observed in all samples except; (i) June site T1 in 2013 and 2014 (see Fig. 1 for site names and locations), (ii) September site T2 in 2013, (iii) July site T4 in 2014, and (iv) WMA in New Zealand, where diatoms were dominant (63.7% ± 31.4).

Figure 2.

Proportions of the dominant photosynthetic microorganisms in river biofilms estimated by microscopic enumerations in Tarn River samples in 2013 (A) and 2014 (B) and in New Zealand river samples in 2013 (C). Stacked histograms represent average proportions of cyanobacteria = light grey, diatoms = grey, green algae = black. In (A) Sites T3 and T5 were only sampled in August 2013. Missing data points in (A) sampling months: June, July in T2 and T4 are due to (i) high flow velocities caused by high rain events, which did not allow us to make the sampling without risk for the operators or/and (ii) the lack of Phormidium biofilm at the site during the sampling campaign. In (C) sites W and WMP are not presented due to missing data (refer to Fig. 1 for site names and locations).

In the Tarn River, the proportion of cyanobacteria varied mostly according to the sampling date (Fig. 2A,B; Supplementary Table S3). The lowest cyanobacterial proportions were observed in June 2013 and July 2014 (Fig. 2A,B) shortly after two large flow events (Supplementary Fig. S1), and the highest were observed in August and September.

In New Zealand rivers, significant differences were observed in cyanobacterial proportions between site WMA and the rest of the sampling sites (ANOVA test, all P < 0.004; Fig. 2C and Supplementary Table S3).

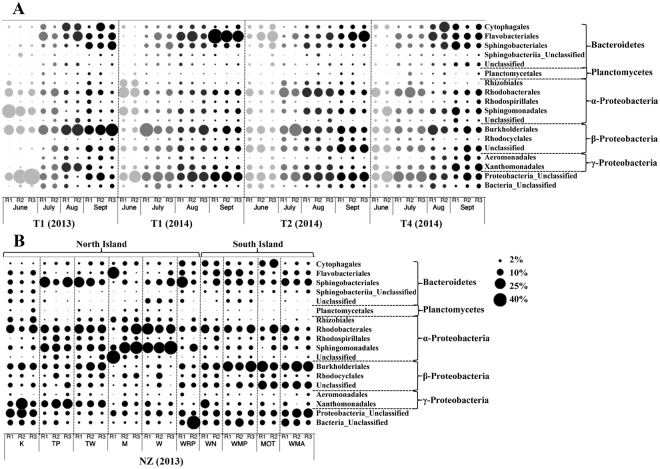

Spatio-temporal variations in bacterial community structure at high taxonomic ranks

Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequences showed that biofilms were dominated by cyanobacteria (mean 84.3% ± 3.5 of the total reads per sampling campaign), mainly belonging to Oscillatoriales order (Supplementary Fig. S2) and to Phormidium (mean 98.5% ± 0.9 of the cyanobacteria reads per sampling campaign). We found the same 16S rRNA dominant Phormidium OTU (with a 97% cut-off) in all rivers (France and New Zealand), which displayed a 100% sequence similarity (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, BLAST analysis on GenBankTM, KF770970) with Phormidium uncinatum. Excluding cyanobacteria and no-hit (CNH), the most abundant bacterial phyla were Proteobacteria (mean 69.4% ± 0.9) and Bacteroidetes (mean 23.6% ± 1.2) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Within Proteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria (mean 26.4% ± 4.4) and Betaproteobacteria (mean 21.3% ± 1.6) and to a lesser extent Gammaproteobacteria (mean 9.0% ± 0.8), were most prominent. Unclassified Proteobacteria also accounted for a high proportion (mean 12.0% ± 4.0) of the reads in this phylum. Within these three classes, most of the sequences were classified in the orders of Rhodobacterales/Sphingomonadales, Burkholderiales and Xanthomonadales, respectively. Bacteroidetes were mainly represented by Flavobacteriales (Tarn River) and Sphingobacteriales (New Zealand rivers; Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table S4). At these high taxonomic ranks, the bacterial structure in biofilms displayed a strong similarity during the two sampling years in Tarn River (Supplementary Fig. S2; Bray-Curtis dissimilarity = 0.18 in Supplementary Table S5) and when comparing Tarn River and New Zealand rivers BC (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity = 0.20 in Supplementary Table S5).

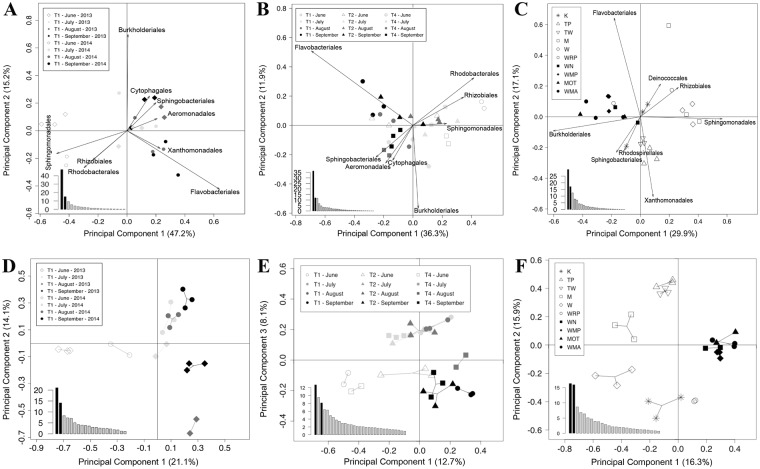

When comparing the occurrences and relative abundances of dominant bacterial orders (≥1%; excluding CNH) in Tarn and New Zealand rivers, it appeared that the global structure of all the BC was maintained among sampling sites (see Fig. 3). However, when performing Principal Component Analyses (PCA) on three different data sets (Tarn 2013 & 2014 Site T1, Tarn 2014 and New Zealand rivers), spatio-temporal variations were evident in the structure of the BCs. The PCA performed on the biofilms collected in T1 sampling station from the Tarn River (Fig. 4A), highlighted on the first axis (47.2% of the total inertia) of the projection, a highly significant distinction (PERMANOVA test, P = 0.001; Table 1) between the samples collected in June and those collected from July to September. These seasonal differences in the structure of the BCs were mainly due to the relative importance of Sphingomonadales, Rhizobiales and Rhodobacteriales orders (ANOVA test, all P < 0.001; Supplementary Table S6). On the second axis of this PCA (15.2% of the total inertia; Fig. 4A), a significant difference (PERMANOVA test, P = 0.002; Table 1) was found between samples collected in 2013 and 2014. In concordance with sampling month differentiation observed in site T1, when considering all sampling sites from Tarn 2014 (Fig. 4B), the same temporal pattern was obtained (first axis explaining 36.3% of the total inertia; PERMANOVA test, P = 0.001; Table 1). The PCA performed on the New Zealand rivers highlighted significant differences (Nested PERMANOVA test, P = 0.02; Table 1) between BCs from the North and the South Islands of New Zealand. These differences were mainly due to the relative abundances of bacteria belonging to Burkholderiales and Sphingomonadales orders (Fig. 4C). Finally, significant differences (Nested PERMANOVA test, P = 0.003; Table 1) were found also at the order level, between BCs from New Zealand rivers and the Tarn River (see PCA Supplementary Fig. S3A).

Figure 3.

Spatio-temporal variation of the most abundant (≥1%) bacterial orders (excluding cyanobacteria and no-hit) associated with Phormidium biofilms: (A) Tarn River at site T1 in 2013 and T1, T2 and T4 in 2014 from June (light grey) to September (black). In 2013 at the Tarn River, only samples from site T1 were selected and showed here as having complete temporal analysis; (B) New Zealand (NZ) rivers (refer to Fig. 1 for site names and locations). Circles represent proportion. R1, R2 and R3 correspond to replicates. Abbreviations: Aug refer to August and Sept to September.

Figure 4.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of bacterial orders (most abundant; ≥1%) (A–C) and operational taxonomic unit (OTU) (D–F). Relative abundances based on 16S rRNA gene fragment sequences (excluding cyanobacteria and no-hit sequences) of biofilm samples from: Site T1 from Tarn River in 2013–2014 (A,D), Tarn River in 2014 (B,E), and New Zealand rivers (C,F) (refer to Fig. 1 for site names and locations). Histograms on the bottom-left part of the graph represent the percentages of variation explained by each principal component. The two components selected for the two-dimensional representation are highlighted in black.

Table 1.

PERMANOVA results within and between sampling campaigns excluding cyanobacteria and no-hits (CNH) at the order and operational taxonomic unit (OTU) levels.

| Sampling campaigns | Source | df | Order level | OTU level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | Pseudo-F | P | MS | Pseudo-F | P | |||

| Site T1 2013–2014 | Month | 3 | 0.166 | 6.32 | 0.001 | 0.440 | 3.71 | 0.001 |

| Year | 1 | 0.111 | 4.24 | 0.002 | 0.506 | 4.27 | 0.001 | |

| Month*Year | 3 | 0.055 | 2.09 | 0.018 | 0.289 | 2.44 | 0.001 | |

| Residual | 13 | 0.026 | 0.119 | |||||

| Total | 20 | |||||||

| Tarn 2014 | Site | 2 | 0.054 | 2.26 | 0.005 | 0.261 | 2.28 | 0.001 |

| Month | 3 | 0.086 | 3.60 | 0.005 | 0.340 | 2.96 | 0.001 | |

| Site*Month | 6 | 0.056 | 2.37 | 0.001 | 0.207 | 1.80 | 0.001 | |

| Residual | 20 | 0.024 | 0.115 | |||||

| Total | 31 | |||||||

| Tarn 2013–2014 | Site | 4 | 0.057 | 2.16 | 0.004 | 0.232 | 1.95 | 0.001 |

| Month | 3 | 0.132 | 5.02 | 0.001 | 0.443 | 3.72 | 0.001 | |

| Year | 1 | 0.124 | 4.72 | 0.001 | 0.557 | 4.67 | 0.001 | |

| Site*Month | 6 | 0.064 | 2.45 | 0.001 | 0.234 | 1.97 | 0.001 | |

| Site*Year | 2 | 0.072 | 2.73 | 0.001 | 0.248 | 2.08 | 0.001 | |

| Month*Year | 3 | 0.059 | 2.23 | 0.002 | 0.297 | 2.49 | 0.001 | |

| Site*Date*Year | 2 | 0.035 | 1.32 | 0.153 | 0.174 | 1.46 | 0.024 | |

| Residual | 33 | 0.026 | 0.119 | |||||

| Total | 54 | |||||||

| New Zealand | Island | 1 | 0.229 | 2.68 | 0.021 | 0.721 | 2.01 | 0.042 |

| Site(Island) | 8 | 0.085 | 3.00 | 0.001 | 0.359 | 3.17 | 0.001 | |

| Residual | 17 | 0.028 | 0.03 | 0.113 | 0.11 | |||

| Total | 26 | |||||||

| Tarn & New Zealand | Country | 1 | 0.247 | 2.82 | 0.001 | 1.337 | 3.84 | 0.001 |

| Site(Country) | 13 | 0.088 | 2.22 | 0.001 | 0.348 | 2.14 | 0.001 | |

| Residual | 67 | 0.039 | 0.04 | 0.162 | 0.16 | |||

| Total | 81 | |||||||

A total of 999 permutations were performed. Site(Country) or Site(Island) means that the term on the left is nested inside the term in brackets. Asterisk denotes interaction between factors. df: degrees of freedom, MS: means of squares. Bold values: P < 0.05.

Spatio-temporal variations in bacterial community structure at the OTU level

Rarefaction curves constructed from the dataset including all the sequences (at least 8,918 sequences per sample) were close being asymptotic for most of them (see Supplementary Fig. S4A–C). After removing CNH sequences (remaining sequence number of at least 402 sequences per sample), the rarefaction curves were not asymptotic. Consequently, further analyses were performed only on the dominant OTUs from the BCs (see Supplementary Fig. S4 D–F).

When all the sequences were taken into account, 534 OTU (24.3%) of the 2,198 OTU were shared by samples collected in Tarn River in 2013 and 2014 and in New Zealand rivers in 2013 (Supplementary Fig. S5A). Similar results were obtained when excluding CNH sequences (283 shared OTU, representing 28.2% of total OTU; Supplementary Fig. S5B). Shared OTUs (=core OTUs) contained a very high number of reads compared to those only present in biofilms from Tarn or New Zealand rivers (Supplementary Fig. S5) and there was a clear relationship between the mean number of reads per OTU and the number of samples in which each OTU was found (see Supplementary Fig. S6). At the genus level, the OTUs belonging to the core species (≥1% of total reads) were represented mainly by Rhodobacter, Pedobacter, Silanimonas, Flavobacterium, Hydrogenophaga, Runella, Tolumonas and Sphingobacterium (50 most abundant OTUs are presented in Supplementary Table S7).

In agreement with the analysis on BCs at the order level, PCA performed at the OTU level reveal the same spatio-temporal variations in BCs structure (Fig. 4D–F). Significant temporal differences (PERMANOVA test, all P = 0.001; Table 1) in BCs were found when comparing samples collected in the Tarn River at site T1 between June and the other months (Fig. 4D; first axis explaining 21.1% of the total inertia) and between the two sampling years (second axis explaining 14.1% of the total inertia). The PCA performed on the BC sampled in 2014 in the Tarn River (Fig. 4E) confirmed the existence of temporal variations with a distinction among samples from June, July-August and September and showed also spatial variations among the different sites (PERMANOVA test, all P = 0.001; Table 1). The structures of BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms from New Zealand rivers located in the North Island display significant differences with those of rivers located in the South Island (Fig. 4F; Nested PERMANOVA test, P = 0.04; Table 1). In addition, BCs from South Island biofilms were tightly grouped (Fig. 4F; Bray-Curtis dissimilarity = 0.45 in Supplementary Table S5), whereas those from the North Island were much more dispersed (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity = 0.61 in Supplementary Table S5). Moreover, biofilms from the North Island followed a gradient of ordination from north to south on the second axis of the analysis (Fig. 4F), except for site K. Finally, significant differences (Nested PERMANOVA test, P = 0.001; Table 1) were found at the OTU level, between BC from New Zealand rivers and those from the Tarn River (see PCA Supplementary Fig. S3B).

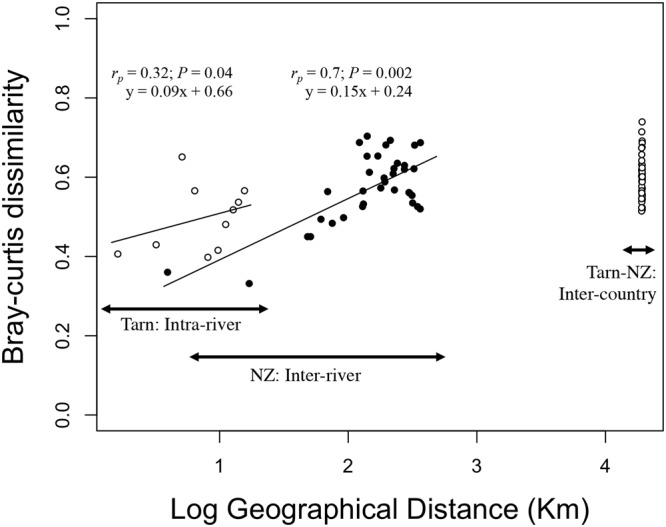

There was a weak significant relationship (Mantel test, rp = 0.32; P = 0.04; Fig. 5) between Bray-Curtis dissimilarities and geographical distances among the BCs collected in five sampling sites of the Tarn River in August 2013 (Fig. 5). Conversely, this relationship was highly significant among BCs sampled in New Zealand rivers (Mantel test, rp = 0.73; P = 0.001; Fig. 5). Finally, while the geographical distance between France and New Zealand is much greater that the geographical distances between New Zealand rivers, the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity values estimated between BCs from Tarn and New Zealand rivers are in the same order of magnitude than those found between the most distant rivers in New Zealand (Fig. 5; Average Bray-Curtis dissimilarity values presented in Supplementary Table S5). A similar curve was found after transforming abundance data to presence/absence data using Jaccard index of dissimilarity (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Figure 5.

Geographic distance and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity relationship in the Tarn and New Zealand rivers. Bray-Curtis dissimilarities were performed on operational taxonomic units (OTUs) based on 16S rRNA relative abundances of pooled replicates excluding cyanobacteria and no-hit. Comparisons were conducted among Tarn River biofilms harvested in August 2013 (open circles on the left), biofilms from New Zealand (NZ) rivers (black circles in the middle) and between Tarn and New Zealand river biofilms (open circles at the right). Mantel statistics are based on Pearson’s product-moment correlation.

Discussion

Numerous studies in the twenty past years have highlighted the major role microbial biofilm communities play in stream ecosystem functioning (see the review of Battin et al.)17. In particular, stream biofilms contain an assemblage of phototrophic and heterotrophic microbial communities, which contribute to primary production and numerous biogeochemical cycles. The relationships between phototrophic and heterotrophic taxa can be positive and negative, and these interactions may also be important in shaping biofilm communities17,18. In addition, it is well known that environmental factors can have direct and indirect influences on the microbial communities of stream biofilms19–21.

In this study, we investigated stream biofilms whose phototrophic component was dominated by cyanobacteria belonging to the Phormidium genus for three reasons. These cyanobacteria are potentially toxic and their proliferations seems to be increasing worldwide22,23. Secondly, biofilms dominated by Phormidium are found in similar environmental conditions in streams (i.e., depth, flow velocity, substrate)24–26. This reduces the number of potential environmental factors that might impact BCs associated with Phormidium and enabled a comparative approach to be performed on these communities between France and New Zealand rivers. Finally, biofilms dominated by Phormidium are characterized by a large thickness (up to several millimetres), which results in specific micro-environmental conditions and cyanobacteria probably constitutes the main source of organic compounds for the BC. Consequently, we anticipated that: (i) BCs associated with Phormidium would display a conserved structure at various spatiotemporal scales, and (ii) that the BCs differ from those living in biofilms dominated by other phototrophic microorganisms, for example diatoms, in the same kind of environments.

In agreement with our hypothesis that the specific micro-environmental conditions provided by thick Phormidium biofilms shape the BCs structure, we showed that all the BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms in the Tarn River and New Zealand rivers display similar patterns in their structure. At higher taxonomic ranks (phylum, class or order), these BCs were dominated by species belonging to Proteobacteria (Alpha- and Betaproteobacteria) and Bacteroidetes phyla, the three most abundant genera being Rhodobacter (Alphaproteobacteria), Flavobacterium (Flavobacteria) and Pedobacter (Sphingobacteria). The dominance of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes is a common feature of BCs in biofilms of streams12,21,27 and lakes28. However, when analysing the few studies available using NGS approaches on BCs from river biofilms, it appears that these BCs are dominated by various genera, including Acidovorax (Betaproteobacteria), Flavobacterium and Polynucleobacter (Betaproteobacteria) in the study of Besemer et al.12; Arenimonas (Gammaproteobacteria), Rhodobacter and Betaproteobacteria-undefined genus in the study of Bricheux et al.29 and Rhodobacter, Exiguobacterium (Firmicutes) and Zymomonas (Alpha) in the study of Peipoch et al.16.

Furthermore, our data indicates that habitat type (benthic versus pelagic life) is a key factor acting on BCs associated with cyanobacteria. The importance of habitat on BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms in rivers is further supported by the fact that these communities display marked differences with those associated with planktonic bloom-forming cyanobacteria in lakes, which are commonly dominated by Betaproteobacteria1,30 (i.e., Comamonadaceae members)30 or Bacteroidetes31,32 (i.e., Flavobacterium, Sediminibacterium31), and in a lesser extent by Alpha- (i.e., Pelagibacter)31 and Gammaproteobacteria1,31 (i.e., Pseudomonas)31.

When comparing BC in biofilms dominated by diatoms and by cyanobacteria in Tarn River, marked differences were found between them at all taxonomic levels. The BCs associated with diatoms in biofilms were largely dominated by Alphaproteobacteria as previously observed in marine environments33, in epilithic lake biofilms34, and in river biofilms18. These findings suggest that BC are at least to some extent dependent on the key phototroph microorganisms in the biofilms, and the resulting micro-environmental conditions. Among the processes that could be involved in the selection of bacterial species inside the biofilms, Becker et al.35 showed that the dissolved organic matter (DOM) produced by diatoms and cyanobacteria is very different, which potentially has a substantial influence on heterotrophic communities utilising it for their growth. Wagner et al.36 also found that the quality of the DOM impacted the functional and structural diversity of BCs in hyporheic biofilms. Phormidium biofilms can be several millimetres thick and form very cohesive biofilms23,37. A recent study has shown that this creates conditions within the biofilm (e.g., pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrient and metal concentrations) that are very different from those of the overlying water37. It is likely that these micro-environmental conditions have a substantial impact on the BC structure, which could partly explain the dominance of particular OTUs into the BCs, regardless of their geographical origin (France or New Zealand). As Phormidium biofilms grow, these within-biofilm conditions probably become more intense and this may explain why marked shifts in BCs were observed during different successional phases4.

We identified a positive relationship between the abundance of reads per OTU and the number of samples in which they were retrieved. This indicates that the most abundant OTUs are widely distributed and constitute the core species of the BC associated with Phormidium biofilms in rivers. A similar positive relationship has been previously described by Humbert et al.38 for pelagic BCs from lakes and by Dougal et al.39 for BCs in the large intestine of horses. As members of the core species, it is probable that these OTUs play a major role in the basic functioning of biofilm BCs while satellite species distributed in a restricted number of samples, are probably involved in the adaptation to local environmental conditions. Many of the dominant OTUs in the biofilms examined in this study are well known for their ability to degrade complex compounds such as recalcitrant humic substances or organic contaminants (e.g., Sphingomonas40 and Hydrogenophaga41) or large organic polymeric proteins and polysaccharides (e.g., Flavobacterium42 and Runella43). Others have been shown to be involved in the nitrogen cycle, including nitrogen fixation and denitrification (e.g., OTUs from Rhodobacter44, Sphingomonas40, Azonexus45, and Hydrogenophaga41). During the early stages of development of the Phormidium biofilms (June and July in Tarn River), numerous reads belonging to Rhodobacter genus were identified. This genus is metabolically diverse, with members that perform anaerobic phototrophy and photoautotrophy to aerobic chemoheterotrophy44. The high abundance of these purple bacteria including OTUs belonging to Burkholderiales, Rhizobiales, Rhodocyclales, Rhodospirillales and Rhodobacterales raises questions regarding their potential contribution to primary production in river biofilms18.

Distance-decay similarities allow variations in beta-diversity across different spatial scales (e.g. Soininen et al.46; Tan et al.47) to be explored. Beta-diversity depends on the sampling scale and should increase with increasing spatial extent of the study area47. In our study, three different scales were taken into account, from local (intra-river), to regional (inter-river) and global (inter-country) levels. Different processes drive beta-diversity at these different spatial scales. For example, topology, altitude, discontinuous habitat, latitudinal gradients in productivity, and climate act as regional scales, while habitat structure and composition act as local filters48.

As expected, the distance-decay relationship estimated between BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms collected in the five sampling stations of the Tarn River (intra-river comparison) was much lower than that found among BCs collected in various rivers in New Zealand (inter-river comparison). However, it was unexpected to find that the genetic dissimilarities between BCs from France and New Zealand were of the same order of magnitude as those found between the most distant rivers in New Zealand. We had anticipated that the larger distance between France and New Zealand would limit the dispersion of bacteria, and that other processes such as climate factors and continental isolation which act as large-scale filters48, would result in much greater differences among these communities. This result is largely due to the presence of several core OTUs, which are highly abundant in Phormidium biofilms from both France and New Zealand.

Collectively these results indicate that in addition to micro-environmental conditions that shape the BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms, the main processes acting on these BCs seems to be mainly related to local environmental conditions rather than to geographic distance per se. This is supported by the study of Lear et al.13 performed across New Zealand where they found that stream biofilm BCs were more influenced by catchment land use attributes than by dispersal limitation and also by Peipoch et et al.16 in USA.

Our data are also interesting to consider in the context of the meta-analysis on stream microbial communities provided by Zeglin20 and on the meta-community concept, which can be defined as a set of local communities linked by dispersal of multiple interacting species49. According to Zeglin20, BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms seem to be largely structured by local heterogeneity and by temporal variations, while longitudinal (from upstream to downstream) differences were less significant. The meta-community paradigms as described by Leibold et al.49 (i.e., patch-dynamic, species-sorting, mass-effect and neutral perspectives) allow us to consider our results in a theoretical framework. The development of thick Phormidium biofilms creates well-defined local environmental conditions (e.g., habitat, chemical gradients, organic matter availability) that may delimit ecological niches leading, by a species-sorting process, to the selection of BCs displaying a similar structure. Inside these biofilms, the local dynamics of species due to stochastic and/or deterministic processes (including seasonal succession) seems to have a marked effect on the BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms as emphasized by the importance of intra-site variations.

In conclusion, our findings obtained on the BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms collected in France and New Zealand have shown that various processes functioning at different temporal and spatial scales, shape these BCs. Among these processes, we found a distance-decay relationship between BCs collected in rivers from NewZealand. Future research should focus on a large scale sampling including other countries. Moreover, this sampling should also take into account the influence of temporal variations in the structure of BCs associated with Phormidium biofilms by targeting them at different phases of their development. Finally, a significant challenge for the future will be also to establish to what extent the recent increase in benthic Phormidium proliferations in river worldwide is due to perturbations of heterotrophic BCs in biofilms, or whether it is a result of changes in environmental factors and processes promoting the development of Phormidium, with subsequent consequences on the BCs.

Methods

Sites description

Samples were collected from nine wadeable rivers in France and New Zealand. Previous studies had identified the presence of potentially toxic benthic cyanobacteria in these rivers50–52. In France, samples were collected at five sites (T1 to T5; see Fig. 1A) in the Tarn River between June and September 2013 and 2014, which is the most favourable period for the growth of Phormidium biofilms. Sites T3 and T5 were only sampled in August 2013 as part of an expanded monitoring campaign. In New Zealand, ten sites located in eight rivers were sampled in February 2013 (see Fig. 1B). The bed substrates at all sites in France and New Zealand were dominated by cobble and boulder (6 to 26 cm length), except at the Kuratau River in New Zealand (site K; Fig. 1B), where sand was the most abundant substrate. Nitrate (NO3-N) and total phosphorus (TP) concentrations were higher at the Tarn River (mean 1.4 ± 0.6 mg L−1 and 0.02 ± 0.01 mg L−1 respectively; data extracted from the French database SIE Adour-Garonne53); compared to values from New Zealand rivers (mean 0.4 ± 0.4 mg L−1 and 0.01 ± 0.01 mg L−1 respectively; mean values collected at each sampling site according to previously described4). At each sampling point, water temperature, pH, flow velocity and depth were measured. In The Tarn River, variations in flow rates during the sampling period at two survey stations (Bedoues located 28 km upstream, and Mostuéjouls located 38 km downstream from Sainte-Enimie) were obtained from hydro France database54. Sites TP and TW were both located in the Tukituki River (North Island) and sites WN and WMP in the Wakapuaka River (South Island; Fig. 1B). Rivers are very dynamic systems and thus biofilms developing in these ecosystems are subjected to changes occurring in water flow/velocities. Missing data points in Fig. 1 are a consequence of (i) high flow velocities caused by high rain events, which did not allow us to make the sampling without risk for the operators or/and (ii) the lack of Phormidium biofilm in the site during the sampling campaign.

Sample collection

For all sampling sites and dates, except for site T1 in June 2013, a grid (10 m × 10 m) was set up in riffle habitat (shallow region of river with fast flow, mainly over 0.3 m s−1). Sampling was performed on ten points selected randomly inside the grid using a random number table. At each sampling point delimited by a single field of view of an underwater viewer (707 cm2), the percentage of coverage of the river substrate colonized by Phormidium biofilms was visually estimated (independently by two operators). Phormidium cover (%) for a single site was consecutively calculated by averaging the estimated values from the 10 sampling points. A single cobble with a Phormidium biofilm was sampled. Biofilms were removed using sterile tweezers. Subsamples were taken for DNA and chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) extraction, and a known area (1 cm2) for later microscopic identification and enumeration (preserved immediately with Lugol’s iodine solution). Samples were stored chilled in the dark, and subsequently frozen (−20 °C), except for the samples for microscope analysis which were stored at 4 °C.

For site T1 in June 2013, where Phormidium development was low (percentage coverage < 5% of the river substrate) and biofilms were thinner, sampling was undertaken at three points along a transect parallel to the water’s edge and positioned at two meters from the shoreline. At each point, all cobbles (5 to 20 cm length) visible in a single field of view of the underwater viewer were collected. The cobbles were scrubbed and the biomass collected in 150 mL of river water. Aliquots (5 mL) were filtered for Chl-a (GF/C Whatman) and DNA extraction (Polycarbonate 0.2 μm GTTP Millipore). Samples were stored chilled in the dark, and subsequently frozen (−20 °C) for later analysis in the laboratory. Subsamples (1 mL) were fixed with Lugol’s iodine solution and stored at 4 °C for later microscopic identification and enumeration.

Enumeration and biomass estimation of the photosynthetic community

Lugol’s iodine preserved samples were homogenized briefly (Ultra-Turrax T25 IKA, Germany, 3 × 2 s, 9.5 min−1) to break up filaments, but avoid cell damage. The samples were diluted in Milli-Q water and identification and enumeration performed using a light microscope (200× magnification, Nikon Optiphot-2, Japan), and a Malassez chamber (Marienfeld, Germany). All cells contained in 25 squares of the Malassez chamber were counted and analysis of triplicate aliquots undertaken. Cell identification and biovolumes were calculated as outlined previously52.

Chl-a concentrations were used as a proxy of biofilm biomass (µg of Chl-a per cm2). Biofilm samples and glass fiber filters with concentrated biomass (for site T1 in June 2013) were placed in Falcon tubes (15 mL) covered with aluminium foil, frozen until analysis, and Chl-a was extracted with methanol. Chl-a concentrations were estimated according to the protocol described previously by Echenique-Subiabre et al.52.

Molecular analysis of biofilm communities

Triplicates subsamples from each site were lyophilized (FreeZone2.5, Labconco, USA) and DNA extracted from ca. 50 mg using a Power Biofilm® DNA Isolation Kit (MOBIO, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Nucleic acid concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry (Nanodrop 1000, Thermo Fischer Inc, USA) and samples stored at −20 °C. A region of the 16S rRNA gene (~394 base pair (bp)) including the variable region V4-V5 was amplified and sequenced using the 515 F and 909 R universal primers55 in a commercial facility (Research and Testing Laboratories, Lubbock, TX, USA) using Illumina MiSeq sequencing technology.

Bioinformatics analysis

The Illumina MiSeq sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene produced 2,085,469 raw sequences. All sequences were processed by the Research and Testing Laboratories (Lubbock, TX, USA), according to their pipeline56. Briefly, after denoising (i.e., removing of short sequences and singletons) and chimera checking, the remaining sequences were clustered using UPARSE pipeline57 at 97% similarity threshold. The centroid sequences of each cluster were run against a database of high quality sequences derived from the NCBI database using the USEARCH global alignment algorithm58. The number of read per sample ranged from 604 to 57,391. Of the 95 biofilm samples sequenced, three were removed from our analyses because an insufficient number of reads was obtained. Rarefying (randomly down-sampling using software R version 3.1.059) resulted in a total of 820,456 16S rRNA sequences (8,918 sequences per sample), which clustered in 2,198 operational taxonomic units (OTUs). In order to study the BCs associated to Phormidium biofilms, a second analysis was performed after removing cyanobacteria and no-hit (CNH) sequences. The number of reads ranged between 32 to 30,560 per sample and a total of 402 sequences per sample were selected for further analysis. Thus, only 82 samples were retained (at least two replicates per sampling site). Rarefying resulted in 32,964 16S rRNA sequences, which clustered in 1,004 OTUs.

OTUs were classified as abundant when they comprised ≥1% of the total sequences, intermediate when between <1% and >0.01%, and rare when ≤0.01% as previously defined by Mangot et al.60.

Statistical analysis

The R software (version 3.1.059) was used for statistical analyses of the data. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. The effect of sampling site and date on cyanobacteria biovolume proportions and abundance of microbial taxa were analysed using two-way ANOVA, followed by multiple comparisons using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc test.

Rarefaction curves were calculated using package ‘vegan’61. Hellinger transformations were undertaken on Illumina sequencing data. Beta-diversity was calculated to measure the variation in BC among sites and dates using Bray-Curtis dissimilarities performed at order and OTU levels (package ‘vegan’). Principal component analyses (PCA) were performed on rarefied and transformed data (Hellinger transformation) using the ‘Ade4TkGUI’ package62 in order to visualise samples distribution based on their order and OTU structures. Permutational Multivariate ANOVA (PERMANOVA)63,64 was performed on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities to test for differences in BC among sites and among sampling times (countries, sites and dates) including factorial and nested designs using package ‘vegan’ and ‘BiodiversityR’65 respectively. Finally, the relationship between geographical distance and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity was performed using the package ‘fossil’66, longitude and latitude coordinates were transformed to kilometres as measured in a straight line. In order to remove temporal variability (month and year), to analyse exclusively Phormidium biofilm samples, and to capture the totality of the sampling sites, only samples from August 2013 were considered for the Tarn River. Therefore, this analysis was performed on biofilms collected at the five sampling sites for the Tarn River, and nine sampling sites from New Zealand rivers (samples from site WMA were excluded because biofilms were dominated by diatoms). Mantel statistic based on Pearson’s product-moment correlation (package ‘vegan’) was performed between dissimilarity matrix and permutation (999) used to evaluate statistical significance.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to K. Tambosco, M.A. Barny and F. van Gijsegem (iEES Paris) and all people who have contributed to the fieldwork. The study received financial support from the French National Agency for Water and Aquatic Environments (ONEMA) and from Adour-Garonne and Rhône-Méditerrannée-Corse Water Agencies. Authors thank the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) for the fellowship, the Partenariats Hubert Curien (PHC) and New Zealand Royal Society Dumont d’Urville exchange program for project funding. S.A.W. and M.W.H. thank the New Zealand Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment Cumulative Effects program (CO1X0803) for funding.

Author Contributions

All authors performed fieldwork and data acquisition; I.E.S. analysed the samples and data; A.Z. provided analytical support; I.E.S., A.Z., S.A.W., C.Q. and J.-F.H. interpreted the results of experiments; I.E.S. prepared the figures; I.E.S. and J.-F.H. drafted the manuscript; All authors edited and revised the manuscript, approved final version of the manuscript and participated in the conception and design of the research.

Availability of Materials and Data

The raw sequencing data supporting the results of this article can be found in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under the study accession number PRJEB23673.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32772-w.

References

- 1.Parveen B, et al. Bacterial communities associated with Microcystis colonies differ from free-living communities living in the same ecosystem. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013;5:716–24. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagatini Inessa Lacativa, Eiler Alexander, Bertilsson Stefan, Klaveness Dag, Tessarolli Letícia Piton, Vieira Armando Augusto Henriques. Host-Specificity and Dynamics in Bacterial Communities Associated with Bloom-Forming Freshwater Phytoplankton. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e85950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu L, et al. Bacterial communities associated with four cyanobacterial genera display structural and functional differences: evidence from an experimental approach. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brasell KA, Heath MW, Ryan KG, Wood SA. Successional change in microbial communities of benthic Phormidium-dominated biofilms. Microb. Ecol. 2015;69:254–266. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0538-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Wit R, Bouvier T. ‘Everything is everywhere, but, the environment selects’; what did Baas Becking and Beijerinck really say? Environ. Microbiol. 2006;8:755–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heino J, et al. Metacommunity organisation, spatial extent and dispersal in aquatic systems: patterns, processes and prospects. Freshw. Biol. 2015;60:845–869. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanson China A., Fuhrman Jed A., Horner-Devine M. Claire, Martiny Jennifer B. H. Beyond biogeographic patterns: processes shaping the microbial landscape. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2012;10(7):497–506. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langenheder S, Székely AJ. Species sorting and neutral processes are both important during the initial assembly of bacterial communities. ISME J. 2011;5:1086–1094. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindström ES, Langenheder S. Local and regional factors influencing bacterial community assembly. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2012;4:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JE, Buckley HL, Etienne RS, Lear G. Both species sorting and neutral processes drive assembly of bacterial communities in aquatic microcosms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013;86:288–302. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nekola JC, White PS. The distance decay of similarity in biogeography and ecology. J. Biogeogr. 1999;26:867–878. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.1999.00305.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Besemer K, et al. Unraveling assembly of stream biofilm communities. ISME J. 2012;6:1459–1468. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lear G, et al. The biogeography of stream bacteria. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013;22:544–554. doi: 10.1111/geb.12046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Astorga A, et al. Distance decay of similarity in freshwater communities: do macro- and microorganisms follow the same rules? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012;21:365–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00681.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heino J, Tolkkinen M, Pirttilä AM, Aisala H, Mykrä H. Microbial diversity and community-environment relationships in boreal streams. J. Biogeogr. 2014;41:2234–2244. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peipoch M, Jones R, Valett HM. Spatial patterns in biofilm diversity across hierarchical levels of river-floodplain landscapes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Battin TJ, Besemer K, Bengtsson MM, Romani AM, Packmann AI. The ecology and biogeochemistry of stream biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:251–263. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zancarini A, et al. Deciphering biodiversity and interactions between bacteria and microeukaryotes within epilithic biofilms from the Loue River, France. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4344. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04016-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fierer N, Morse JL, Berthrong ST, Bernhardt ES, Jackson RB. Environmental controls on the landscape-scale biogeography of stream bacterial communities. Ecology. 2007;88:2162–2173. doi: 10.1890/06-1746.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeglin LH. Stream microbial diversity in response to environmental changes: review and synthesis of existing research. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Besemer K. Biodiversity, community structure and function of biofilms in stream ecosystems. Res. Microbiol. 2015;166:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quiblier C, et al. A review of current knowledge on toxic benthic freshwater cyanobacteria - ecology, toxin production and risk management. Water Res. 2013;47:5464–79. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAllister TG, Wood SA, Hawes I. The rise of toxic benthic Phormidium proliferations: a review of their taxonomy, distribution, toxin content and factors regulating prevalence and increased severity. Harmful Algae. 2016;55:282–294. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heath MW, Wood SA, Ryan KG. Spatial and temporal variability in Phormidium mats and associated anatoxin-a and homoanatoxin-a in two New Zealand rivers. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2011;64:69–79. doi: 10.3354/ame01516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heath MW, Wood SA, Brasell KA, Young RG, Ryan KG. Development of habitat suitability criteria and in-stream habitat assessment for the benthic cyanobacteria. Phormidium. River Res. Appl. 2015;31:98–108. doi: 10.1002/rra.2722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Echenique-Subiabre, I. Mieux comprendre les conditions de développement et la biodiversité microbienne des biofilms en rivières pour mieux les surveiller - Cas particulier des biofilms à Cyanobactéries. Université Pierre et Marie Curie (UPMC) – PhD Thesis (2016).

- 27.Anderson-Glenna MJ, Bakkestuen V, Clipson NJW. Spatial and temporal variability in epilithic biofilm bacterial communities along an upland river gradient. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008;64:407–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parfenova VV, Gladkikh AS, Belykh OI. Comparative analysis of biodiversity in the planktonic and biofilm bacterial communities in Lake Baikal. Microbiology. 2013;82:91–101. doi: 10.1134/S0026261713010128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bricheux G, et al. Pyrosequencing assessment of prokaryotic and eukaryotic diversity in biofilm communities from a French river. Microbiol. Open. 2013;2:402–414. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louati I, et al. Structural diversity of bacterial communities associated with bloom-forming freshwater cyanobacteria differs according to the cyanobacterial genus. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai H, Jiang H, Krumholz LR, Yang Z. Bacterial community composition of size-fractioned aggregates within the phycosphere of cyanobacterial blooms in a eutrophic freshwater lake. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eiler A, Bertilsson S. Composition of freshwater bacterial communities associated with cyanobacterial blooms in four Swedish lakes. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;6:1228–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amin SA, Parker MS, Armbrust EV. Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012;76:667–84. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruckner CG, Bahulikar R, Rahalkar M, Schink B, Kroth PG. Bacteria associated with benthic diatoms from Lake Constance: phylogeny and influences on diatom growth and secretion of extracellular polymeric substances. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:7740–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01399-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker JW, et al. Closely related phytoplankton species produce similar suites of dissolved organic matter. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner K, et al. Functional and structural responses of hyporheic biofilms to varying sources of dissolved organic matter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:6004–6012. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01128-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood SA, Depree C, Brown L, McAllister T, Hawes I. Entrapped sediments as a source of phosphorus in epilithic cyanobacterial proliferations in low nutrient rivers. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Humbert J-F, et al. Comparison of the structure and composition of bacterial communities from temperate and tropical freshwater ecosystems. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;11:2339–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dougal K, et al. Identification of a core bacterial community within the large intestine of the horse. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glaeser, S. P. & Kämpfer, P. In The prokaryotes, Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria(eds Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E. F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E. & Thompson, F.) 641–707, 10.1007/978-3-642-30197-1 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

- 41.Willems, A. In The prokaryotes, Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria(eds Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E. F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E. & Thompson, F.) 777–851, 10.1007/978-3-642-30197-1 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

- 42.McBride, M. J. In The prokaryotes, Other Major Lineages of Bacteria and the Archaea (eds Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E. F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E. & Thompson, F.) 643–676, 10.1007/978-3-642-38954-2 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

- 43.McBride, M. J., Liu, W., Lu, X., Zhu, Y. & Zhang, W. In The prokaryotes, Other Major Lineages of Bacteria and the Archaea (eds Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E. F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E. & Thompson, F.) 577–593, 10.1007/978-3-642-38954-2 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

- 44.Pujalte, M. J., Lucena, T., Ruvira, M. A., Arahal, D. R. & Macian, M. C. In The prokaryotes, Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria (eds Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E. F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E. & Thompson, F.) 439–512, 10.1007/978-3-642-30197-1 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

- 45.Oren, A. In The prokaryotes, Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria(eds Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E. F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E. & Thompson, F.) 975–998, 10.1007/978-3-642-30197-1 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

- 46.Soininen J, McDonald R, Hillebrand H. The distance decay of similarity in ecological communities. Ecography. 2007;30:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2007.04817.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan L, Fan C, Zhang C, von Gadow K, Fan X. How beta diversity and the underlying causes vary with sampling scales in the Changbai mountain forests. Ecol. Evol. 2017;7:10116–10123. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barton PS, et al. The spatial scaling of beta diversity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013;22:639–647. doi: 10.1111/geb.12031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leibold MA, et al. The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecol. Lett. 2004;7:601–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cadel-Six S, et al. Different genotypes of anatoxin-producing cyanobacteria coexist in the Tarn River, France. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:7605–14. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01225-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wood SA, et al. First report of homoanatoxin-a and associated dog neurotoxicosis in New Zealand. Toxicon. 2007;50:292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Echenique-Subiabre I, et al. Application of a spectrofluorimetric tool (bbe BenthoTorch) for monitoring potentially toxic benthic cyanobacteria in rivers. Water Res. 2016;101:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Système d’Information sur l′Eau Adour-Garonne. Agence de l’Eau Adour-Garonne Available at: http://adour-garonne.eaufrance.fr/accesData/ (Accessed: 16th August 2016).

- 54.Banque Hydro Eau France. Ministère de l’Ecologie, du Développement Durable et de l’Energie Available at: http://hydro.eaufrance.fr (Accessed: 1st December 2014).

- 55.Wang Y, Qian P-Y. Conservative fragments in bacterial 16S rRNA genes and primer design for 16S ribosomal DNA amplicons in metagenomic studies. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Data Analysis Methodology. Research and Testing Laboratories Available at: http://rtlgenomics.com (Accessed: 11th July 2014).

- 57.Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org/ 2014.

- 60.Mangot J-F, et al. Short-term dynamics of diversity patterns: evidence of continual reassembly within lacustrine small eukaryotes. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;15:1745–58. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.3-3, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/ (2016).

- 62.Thioulouse, J. & Dray, S. Interactive multivariate data analysis in R with the ade4 and ade4TkGUI packages. J. Stat. Softw. 22, 1–14 (2007).

- 63.Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 64.McArdle BH, Anderson MJ. Fitting multivariate models to community data: a comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology. 2001;82:290–297. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0290:FMMTCD]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kindt RBR. Package for Community Ecology and Suitability. Analysis. R Package Version. 2017;2:8–3. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vavrek, M. J. fossil: Palaeoecological and palaeogeographical analysis tools. R Package Version 0.3.7, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/fossil/ (2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data supporting the results of this article can be found in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under the study accession number PRJEB23673.