Abstract

When working with isolated islet preparations, measuring the volume of tissue is not a trivial matter. Islets come in a large range of sizes and are often contaminated with exocrine tissue. Many factors complicate the procedure, and yet knowledge of the islet volume is essential for predicting the success of an islet transplant or comparing experimental groups in the laboratory. In 1990, Ricordi presented the islet equivalency (IEQ), defined as one IEQ equaling a single spherical islet of 150 μm in diameter. The method for estimating IEQ was developed by visualizing islets in a microscope, estimating their diameter in 50 μm categories and calculating a total volume for the preparation. Shortly after its introduction, the IEQ was adopted as the standard method for islet volume measurements. It has helped to advance research in the field by providing a useful tool improving the reproducibility of islet research and eventually the success of clinical islet transplants. However, the accuracy of the IEQ method has been questioned for years and many alternatives have been proposed, but none have been able to replace the widespread use of the IEQ. This article reviews the history of the IEQ, and discusses the benefits and failings of the measurement. A thorough evaluation of alternatives for estimating islet volume is provided along with the steps needed to uniformly move to an improved method of islet volume estimation. The lessons learned from islet researchers may serve as a guide for other fields of regenerative medicine as cell clusters become a more attractive therapeutic option.

Keywords: islet, islet equivalent, dithizone, ATP, oxygen consumption rate, kansas method

Islets and the Significance of Volume Measurements

Islets of Langerhans are small clusters of endocrine cells found in the pancreas, surrounded by exocrine tissue. They contain the only insulin-producing cells of the body (the β-cells), along with other hormone-releasing cells including glucagon-positive α-cells, somatostatin-positive δ-cells, ghrelin-positive ∊-cells and cells that produce pancreatic polypeptide. When islet function is sufficiently compromised, either by autoimmunity or other means, diabetes ensues. The first report in 1869 of cells within the pancreas that functioned beyond producing digestive enzymes came from the German medical student, Paul Langerhans. He found small round clusters of cells that stained differently than the rest of the pancreas, but whose function was unknown1. After 20 years, the physiologist, Oskar Minkowski and the physician Joseph von Mering showed that when the pancreas was removed from a dog, it became diabetic2.

Scientific advances rapidly expanded the understanding of the pancreatic endocrine function and its relationship to diabetes, ultimately leading to the purification of insulin from islets by Dr. Frederick Banting and medical student Charles Best along with biochemist James Collip2. Subsequently, the process of extracting bovine or porcine insulin became routine, producing large quantities, able to treat people with type 1 diabetes in North America. Yet, the isolation of intact islets remained a challenge. It was not until the 1960s and 70s that groups, including the laboratory of Dr. Paul Lacy, developed a procedure to isolate islets without massive cellular damage and transplant them into diabetic rats, reversing the diabetes3,4. At that point, the ability to measure and control the volume of islet tissue became essential.

Islets are naturally formed within the pancreas as spherical structures ranging in sizes from 30 μm to >400 μm in diameter5–8. This range of diameters appears relatively similar across species with the exception of rabbits, cats, and birds, which have smaller islets with maximum diameters of <200 μm. Table 1 summarizes findings from 24 studies reporting either the size range or the average diameter of islets from different species. To calculate the range of diameters from multiple sources, the maximum range across studies was recorded. When results from specific studies were dramatically different from a group, they were listed in Table 1 separately. Feline islets have been reported to be difficult to isolate and smaller in size, but publications of their average diameters are missing. Porcine islets were initially reported as small, but the results were likely due to suboptimal enzymatic isolation procedures and small samples sizes9, since publications using different techniques have obtained larger porcine islets in the range of 50–250 μm10–12. For human islets, research laboratories have reported islet diameters of <200 μm8,9. However, in one case the researchers used only one donor for their analysis9. Our own work surveying islets from 17 human donors (11 male and 8 female) found a range of islet diameters of 50–350 μm13, in agreement with later work comprised of over 200 human donor pancreata with average diameters close to 100 μm14,15. Other studies have identified even larger human islets, confirming sizes greater than 400 μm in diameter, but never providing an upper value for the range5,16. It is important to note that all of the values listed in Table 1 are from isolated islets, which may differ from islets within the pancreas. A thorough study of islet size in situ demonstrated only a slight decrease compared with diameters measured after isolation15. While it is typically assumed that the size range in situ is closer to the in vivo condition, the act of fixing and slicing tissues for in situ staining can also alter tissue morphology, so the exact in vivo islet size range is not certain.

Table 1.

Average islet diameters along with size ranges, when available, are listed according to species.

| Species | Diameter range (μm) | Average diameter (μm) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 30 to >400 | 108 ± 6 | 5,6,8,13,15,16,17–19 |

| 20–180 | 50 ± 29 | 9* | |

| Rat | 30–350 | 115 ± 5 | 20–22 |

| Mouse | 20–350 | 116 ± 80 | 9,23,24 |

| 154 ± 47 | 25 * | ||

| Monkey | 25–340 | 67 ± 38 | 9,26 |

| Adult pig | 50–250 | 156 ± 8 | 8,11,12,27,28 |

| 20–90 | 49 ± 15 | 9* | |

| Fetal pig | NR | 83 ± 1 | 10 |

| Rabbit | 25-160 | 64 ± 28 | 9 |

| Canine | 50–375 | 158 ± 2 | 29 |

| Goat | NR | 50 ± 250 | 30 |

| Bird | 10–50 | 24 ± 6 | 9 |

For the size range, the maximum range across studies was recorded.

NR: not reported.

* When results from specific studies were dramatically different from others in that species, that report was listed separately.

Owing to inherent variations in size within and across species, an accurate method to estimate the volume of isolated islets in a preparation is essential. One cannot compare one laboratory experiment with another, or examine the effects of an experimental procedure with respect to a control group, without knowledge of the islet volume used in each condition. In the clinical setting, knowledge of the total islet volume transplanted is essential, and often predicts the success of the transplant procedure31,32. In fact, in single-donor transplants, the insulin requirements of the recipient at the time of the transplant and the volume of islets transplanted were the two factors that correlated with successful transplantation and insulin independence33. Conversely, an excessive volume of islets transplanted can put the recipient at risk for elevated portal pressure and internal bleeding34, because currently islets are infused into the portal vein for most human islet transplants. Therefore, the correct dose (volume) of islets is essential for a successful transplant.

Not only is total islet volume important in the success of transplants, the size of those islets is vitally important. Our lab showed that small islets (<125 μm) resulted in more successful islet transplants compared with the same volume of large islets in rats22. That finding was subsequently corroborated in mice24,35, rats21, goats30, and humans36–38. The improved outcomes with smaller islets is presumed to be due to better diffusion characteristics, because core cell death can quickly be measured in isolated islets >150 mm in diameter39. Factors beyond core cell death may also play a role. We showed that small human islets contained statistically more insulin-containing β-cells than large islets40, and other labs have documented smaller islet cells in the human pancreas that could also alter β-cell density between different sizes of islets41. While small human islets contribute minimally to the total islet volume, when calculated by islet equivalency (IEQ), the same is not true for other species. For example, our own experience working with canine islets, determined that islets <50 μm in diameter make up 16% of the total islet preparation.

History of the IEQ

In the 1980s, a method for identifying islet cells, by staining with dithizone, provided an avenue for differentiating endocrine from exocrine tissue in a preparation42. While this technique helped determine the purity of an islet prep, there was little agreement on a standard method for quantifying islet mass. In 1990, Ricordi, along with a distinguished list of contributors, proposed the islet equivalent (IEQ) at the Second Congress of the International Pancreas and Islet Transplantation Association, as a means of normalizing islet volume43. This procedure standardized islet volume measurements and greatly enhanced islet research. It is based on the calculation that one IEQ corresponds to the tissue volume of a perfectly spherical islet with a diameter of 150 µm43. In 2010, an extensive study by Bonner-Weir’s lab estimated that one IEQ was comprised of 1560 individual cells44.

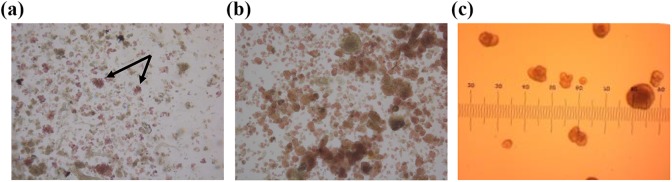

The procedure outlined by Ricordi is relatively easy to use and requires little in the way of instruments. First, a sample of the dithizone-stained islets are viewed under a brightfield microscope45, allowing the researcher to differentiate the islets (stained red) from the exocrine cells. Fig. 1(a) provides an example of a feline islet isolation prep with a mixture of islets (stained red) and exocrine tissue (brown). Feline islets tend to be small and do not contain a smooth spherical perimeter. Arrows point to a few of the larger feline islets. It is important to note that there is also variation in the intensity of the dithizone staining, with some islets appearing deep red, and others containing a pink hue. In general, canine islets (Fig. 1(b)) are larger, but also illustrate few truly spherical shapes. Individual islets are counted and their diameters estimated using the size grid in the microscope binocular. Fig. 1(c) shows human islets within the microscope’s binocular grid, which is the method used by technicians to place them in size categories. With a 4× objective, the divisions on the eyepiece are calibrated to 50 μm. Rather than recording exact diameters for each islet, the technician simply “bins” the islets into 50 μm increments from 50 to 350 μm diameters. The number of islets in each size bin is multiplied by a unique factor that converts the islet number and diameter into IEQs43,46. The result is a simple method that can be completed in a timely manner.

Fig. 1.

Examples of isolated islet preparations. (a) An example of a crude feline islet preparation stained with dithizone (red hue) to differentiate endocrine tissue (islets) from exocrine tissue. The significant variation in size and shape of the red-stained islets can be clearly seen in the image, along with variation in the intensity of the dithizone stain. (b) An example of a canine islet prep stained with dithizone. By comparison the islets are larger in size, but also non-uniformly shaped or stained. (c) Dithizone-stained human islets viewed through a microscope binocular with a grid used to categorize islet sizes into bins for IEQ calculations.

IEQ: islet equivalency.

After its introduction, the Ricordi method rapidly became the standard volume estimation procedure and remained that way through the present. Currently, the IEQ is used to estimate the yield of islets isolated from a donor, and the IEQ per kg of body weight is the unit used to report the graft amount transplanted into the patient4,31,47–52. In the research laboratory, IEQ is commonly applied to normalize the volume of islet tissue between preparations for functional assays such as insulin secretion9,22,37,53–56.

Issues with IEQ Counts

In 2010 a multicenter study designed to examine the IEQ procedure in detail was published57. The same micrographs of human islets were scored for IEQ by 36 different technicians at 8 clinical sites. Overestimation of the IEQ occurred approximately 50% of the time, and the intra-technician coefficients of variation from one repeat count ranged from 0 (technician placed the same islet into the same size category on multiple occasions) to a maximum of approximately 43%57. The wide variation is understandable, given the subjective nature of the binning process illustrated in Fig. 1(c). The results from the multicenter study illuminated the difficulty in determining islet volume using the method, and underscored the poor validity and reliability of IEQ measurements.

From its introduction to the present, the accuracy of the IEQ measurement has been challenged5,7,20,57–59. One of the most consistent criticisms of the IEQ has been its mathematical basis on the ideally spherical 150 μm diameter islet equaling one IEQ. In fact, most islets are not spherical, but are irregularly shaped, both in situ and in culture20,49,59–61. Fig. 1 illustrates that the spherical nature of islets can vary between species, and also between preparations.

Our own work confirmed the irregularity of human islets using video capture as they were rolled through a custom-made chamber13. A measurement of the three largest dimensions in mutually perpendicular directions of the isolated islets was calculated. In a perfect sphere, the three major dimensions a, b, and c would be equal (a = b = c). However, the measured ratios were an average of b/a = 0.82 and c/a = 0.7, suggesting that islets, especially large islets, are predominantly ellipsoidal in shape13. The findings support independent research published in dissertation form, showing diameter ratio values of an average of 0.660.

Islet circularity is another method of estimating the overall spherical shape of islets. Circularity varies depending on the overall size of the islet with large islets having less circularity18,20. Our own unpublished calculations of circularity, based on two-dimensional microscopic images, indicated that small islets had a circularity value of 0.801 ± 0.006, while large islets isolated from the same rats had an average circularity of 0.740 ± 0.029. There have been reports that the location within the pancreas and the presence or absence of disease can also affect islet circularity18.

An additional problem with the IEQ measurements is the process of binning the islets into 50 μm size categories, rather than using the actual diameter measurement. In fact, the procedure of binning islets into 50 μm size ranges may alone lead to an overestimation of IEQ5,59, meaning that the technicians estimate the diameters to be larger than they are, and place them in larger diameter categories during binning. To test this hypothesis, we measured the diameter of individual islets, and then grouped them following the Ricordi size categories. The islets were subsequently dispersed into single cells and individual cell numbers were counted using an automated cell counter. The cell number was divided by the original islet diameter or by the Ricordi diameter category assigned by the technician. When the cells/islet diameter were calculated, the average was 3.5 ± 0.3 cells/μm. However, when the same data were normalized to the Ricordi islet diameter category the value was 2.8 ± 0.2 cells/μm (n = 4 rats). Although not statistically different, the results demonstrate that normalizing the data by 50 μm islets size groupings, rather than the actual diameter, caused a 20% under-estimation of cell density in our laboratory. Further evaluation of our own internal process determined that the staff were overestimating the actual diameter during the binning process, thus skewing the data.

In addition, the original Ricordi binning procedure excluded islets below 50 μm in diameter. This limitation was understandable, because in humans and rodents the small islets represent a minimal percentage of the total volume. In rodents more than 50% of the total β-cell area comes from the largest 2% of islets62. Yet, that relationship is not true for all species. As shown in Table 1, the average islet diameter in certain animals such as birds, rabbits, monkeys, and pigs is lower, shifting the size distribution towards smaller islets. Further, small islets appear to be the most plastic, able to respond to conditions such as pregnancy and aging, and are spared in type 2 diabetes63, but affected during disease states such as type 1 diabetes64. Thus, excluding them from the volume calculation might underestimate the importance of those islets.

In 2009, Ricordi’s laboratory recognized that ignoring a large percentage of islets could affect the IEQ conversion. Adjustments were made to the original IEQ calculations, along with the addition of a conversion factor for islets under 50 μm, resulting in a downward adjustment of the IEQ values5. However, when theoretical cell numbers were plotted for islets of varying diameters using the original method and the revised calculations, the actual Buchwald correction was small and significant differences could only be detected for large islets (over 250 μm in diameter)13,20. A year later another mathematical adjustment to the conversion equation was proposed by Kin65. Again, the changes resulted in minor adjustments to the overall IEQ counts.

Attempts at Improving Islet Volume Measurements

To avoid the subjective nature of diameter determination and size binning that is inherent in the IEQ procedure, several digital image analysis methods have been proposed to replace the manual procedure23,49,57,61,66–68. These procedures aim to improve the reliability of the islet count and reduce the time required to estimate islet volume for transplantation. Islet volumes calculated from images using MetaMorph and ImageJ software have been shown to be reliable, yet the final step in the described process still bins the islets into size categories and converts them to IEQ values. In an important paper comparing manual size estimation with computer-assisted digital image analysis, the variability of standard manual counting methods was clear. The digital process was superior for determining purity and viability in a good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compliant manner69.

While the need for automation, along with digital imaging was identified as early as 199570, a fully automated instrument for islet volume assessment was not developed until 201614. The Islet Cell Counter is an integrated imaging device with software created specifically to analyze the dithizone-stained islets, providing both IEQ and purity values for each sample14. The instrument is GMP compliant and has been shown to be superior to manual counting for islets between 50 and 400 μm in diameter. However, the software bins the islet diameters into the same 50 μm groups and calculates an IEQ as the final output. Other groups with unique digital analysis procedures also incorporate a final step in volume estimation with a conversion to IEQ14,23,68,69,71. As stated earlier the process of binning islets into categories based on their diameter may introduce its own errors. Analysis of islet images based on individual islet diameters or islet area illustrated that when using area instead of diameter, the total IEQ changed14. One group from Prague used digital imaging with conversion based on an assumed ellipsoidal shape, rather than the elusive spherical islet61. More recently another lab has confirmed that they are working on new algorithms to better account for the non-spherical shape of islets71.

Non-IEQ Methods

Methods for determination of islet volume that avoid the IEQ altogether have been developed, but none have been widely adapted. In 1992, a measurement of total zinc content was proposed as a way to eliminate the visual estimation of islet diameters72. A fluorescent zinc tag can be used to quickly stain for intracellular zinc levels. One concern was that, while zinc is in higher concentrations in islet cells, it is present in all cells, including exocrine tissue. However, experiments purposefully contaminating samples with up to 50% exocrine tissue, did not appreciably alter the results. The procedure was relatively simple, required only a common plate reader, and worked well in rat and human islet isolations72. Yet it was never widely accepted as a popular method for volume normalization or purity assessment.

Counting nuclei with stains like Hoechst or 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) or using automation to count liberated nuclei have all been proposed as methods for determining islet cell numbers7,73. Alternatively, DNA content can be measured as another indicator of total cells in the sample. The validation of the nuclei counts obtained through flow cytometry has been compared with DNA concentration measurements and found to be linear. The advantage with both DNA content measurements and nuclei counting is that they are less subjective or prone to error73,74. However, neither differentiate between islet and non-islet cells. Thus, additional tests for sample purity must be completed44. When nuclei counting was added to microscopic evaluation of islet purity, the precision was high and when compared with manual IEQ calculations, the results once again showed that IEQ measurements over-estimate the islet volume by up to 90%44.

Unfortunately, DNA measurements have their own challenges. Colton et al. conducted a thorough comparison of DNA measurements using different fluorescent probes and found significant differences between assays and the sources of the islets, which might be due to the DNA degradation in shipped islets73. We have used total DNA measurements to evaluate the accuracy of the Ricordi IEQ method. Our results show wide variations in the DNA/IEQ, depending on the size of the islets and the quality of the preparation20, but that variation was resolved when the same DNA data were normalized to cell number.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is essential in insulin secretion, is an alternative indicator of islet volume, and can be measured directly with bioluminescent assays. ATP and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) measurements have been shown to closely correlate with insulin secretion, but not the release of glucagon75. Results from several labs have suggested that the ATP/ADP ratio is a strong predictor for the success of islet transplants and should be central to the islet quality control prior to transplantation76–80. Others have suggested that the ratio of ATP/DNA is more predictive of transplant outcomes than ATP/ADP81. Like DNA and zinc, one might assume that measurements of ATP and ADP are not specific to endocrine tissue. However, islet ATP and ADP are somewhat different, because within the islet the ATP/ADP ratio is responsive to stimuli, which differentiates it from other cells76. Thus, a high ATP/ADP ratio typically indicates healthy islet cells and can be associated with better insulin secretion75. In most settings, ATP and ADP would be used as an estimate of islet health and function, not volume. However, we should not eliminate it as a measure of islet volume, if an accurate calibration can be made between these values and current islet volume measurements.

Another metabolic measure is the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) first applied to islets in the late 1990s82,83. A special OCR chamber, equipped with fiber-optic sensors that measure oxygen partial pressure over time, is required for the procedure. When tested prior to transplants into diabetic mice, the OCR output divided by DNA content was 89% sensitive and 77% specific in predicting the reversal of diabetes after the islet transplant82. The sample of islets needed to reliably use OCR as a predictive tool is relatively large (500–2000 IEQ). While this may be only a small fraction of islets used in a clinical islet transplant, it would be a large percentage of islets used in a rodent study, for example. Thus, its utility is likely applicable only to the clinical setting, and again may be best suited to analyze the functional islet mass. In fact, both ATP measurements and OCR may be better measures of the volume of functional islets. Studies have shown that in vivo β-cell function and mass can change independently. In type 1 diabetes, function is lost first, while islet volume loss occurs later in the disease progression (reviewed by Chen et al.84). Thus, functional islet volume may be a more important parameter to measure when trying to predict transplant success.

Large particle flow cytometry offers another option of islet volume measurements. These instruments are based on flow cytometry principles, but can analyze and sort particles ranging from 0.4 to 1.5 mm in diameter. They can count and sort islets based on size or fluorescent markers, and they are available from several manufacturers. We utilized the technology to separate large and small islets based on a 100 μm diameter cut-off point39. Sorting the islets through the large particle cytometer did not alter function or viability when compared with manual separation of the same samples. The instrument provides data on the Time of Flight (a measure of islet diameter), extinction (indicating individual islet density) and can also quantify fluorescence tags39. Fernandez et al. 85 utilized large particle flow cytometry to make islet volume measurements. Unfortunately, rather than converting Time of Flight directly into islet diameters and then into volume, the authors converted the Time of Flight values back to IEQs.

As explained previously, categorizing islet diameter in 50 μm groups offers an inferior method to estimate islet volume. We developed a new volume estimation procedure based on cell numbers that avoided the IEQ calculations13,20. Using rat islets, we placed nearly 350 individual islets, ranging in size from 50 to 350 μm in diameter, into wells with a single islet per well. After measuring two to four diameters for each islet, we dissociated them into single cells and counted the cells per well using an automated imaging system20. All of this was done within the same well and without washes to avoid loss of cells. A calibration curve was then created, based not on theoretical islet shapes, but on measured cell numbers. The equation allows cell numbers to be calculated from islet diameters of any specific size, rather than requiring the binning step. The user measures the islet diameter and plugs it into a conversion equation that calculates the number of cells in that islet. We call this method of volume estimation the Kansas method.

The procedure requires no special equipment and can be used with any digital imaging system or manual measurements. Furthermore, it no longer requires binning of islet diameters into 50 μm categories, but can convert an islet of any size directly into an estimated cell number. We determined that separate cell number conversion equations were necessary for human13 and rat islets20. The Kansas method has been integrated into spreadsheets that automatically calculate cell numbers from any measured islet diameter between 20 and 350 μm and has been placed on our website for free download at http://www.ptrs.kumc.edu/kansasmethod/. Different spreadsheets are available for human and rat conversions. To reduce errors further, the approach can blend with automated imaging for exact diameter measurements fed into the Kansas method spreadsheet.

In previous publications, we illustrated the overestimation of the volume of large islets with IEQ and demonstrated that using the Kansas method corrected the error. More recently, we have found that the Kansas method predicted successful islet xenotransplants in a diabetic mouse model, while converting the islet dose based on IEQ failed. Table 2 summarizes a series of transplants of canine islets into diabetic NOD-SCID mice in which the transplanted volume was calculated as cells/mouse or IEQ/mouse. When calculated as IEQ, mice from each group receiving a low dose (2500 IEQ), a moderate dose (3500 IEQ) and a high dose (4000 IEQ) were reversed of diabetes. Thus dose, when calculated by IEQ did not correlate to transplant outcome. However, when the same transplants were calculated based on cell numbers, the values provided a data-driven cut-off point for successful transplants. No transplants under 5.13 M fully reversed diabetes, while transplants with over 6 million cells were successful 100% of the time. We are expanding this study with more transplants in the 5.5–6.25 M cell range to refine the correlation between cell number and transplant success in the rodent model. One explanation for the difference between the results with normalization by IEQ or cell number is that the islet preps containing a higher percentage of small islets were more likely to be successful36. In fact transplant Group 1 contained 57% of the islets under 100 μm in diameter, while Group 3 contained 73% small islets.

Table 2.

Results from studies transplanting canine islets into diabetic NOD-SCID mice.

| Transplant group | Outcome | Cells/mouse | IEQ/mouse |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100% partial response | 5.00 M | 2500 |

| 2 | 33% failure | 5.13 M | 3500 |

| 33% partial response | |||

| 33% normal glycemia | |||

| 3 | 100% normal glycemia | 6.17 M | 2500 |

| 4 | 100% normal glycemia | 7.25 M | 4000 |

Transplants on the left side of the table show the volume of islets transplanted into the mice based on IEQ. When calculated as IEQ, some of the mice in each group responded fully to the transplant with normal glycemia. However, when the same transplants were calculated based on cell numbers (right side of table), the results suggest that transplants with 6.17 million cells or more were successful 100% of the time. N = 10 mice.

IEQ: islet equivalency.

Calculating islet volumes based on cell numbers rather than IEQ results in several shifts in thinking about islet preps. For example, IEQ values for human islet preparations have consistently shown that small islets make up a very minimal percentage of the total islet volume. This thought is so pervasive, that it is rarely questioned. When we analyzed human islet preps using IEQ, we found that those islets under 50 μm in diameter made up only 6.6% of the total volume. However, when the same preparations are first converted to cell number, the contribution of small islets (≤50 μm) was 17% of the total. Thus, utilizing the cell number conversions in the Kansas method may help to clarify some of the contradictory data found in the literature.

Sampling Error

To suggest that abandoning the IEQ volume measurement for one of the newer alternatives will correct all errors inherent in the volume estimation process would be wrong. While the non-IEQ methods of volume estimation can overcome some of the flaws of the IEQ method, all attempts to determine islet volume face the issue of sampling error. Because the islets are heavy and quickly settle in liquid, the time, location, and even speed of pipetting will alter the number of islets in the aliquot and thus introduce errors in volume estimations. Current studies designed to measure inter-rater reliability between technicians conducting islet testing, typically use images of islet preps to test the technicians, completely missing the additional error introduced by different pipetting techniques. While we, and others, have tried to minimize the error with strict standard operating procedures and multiple samples per prep, there appears to be no way to avoid sampling error currently. Further, large dilution factors used in the clinical setting only exaggerate the issue.

Conclusion

Over the past 25 years, the IEQ measurement to estimate islet volume has been a useful tool that has moved the fields of islet research and clinical islet transplants forward. Yet today there are likely better options, including computer programs for automated area or diameter, or fluorescence/luminescence measurements that remove the human error intrinsic in the IEQ procedure. Islet transplants, and all of the supporting research, have been at the forefront of the cell therapy field. As other cell therapies find their way to clinical reality, it is likely that several of them will also be based on cell clusters. Thus, accurate methods to estimate transplant volumes of islets could have implications for various regenerative medicine therapies. Unfortunately, improved procedures will never be widely adopted until leaders in the islet transplant field advocate advanced methods and pick one of the many scientifically sound options as the new gold standard. Until then, we are all left with a less optimal procedure that we cannot avoid if we want to disseminate our laboratory studies or conduct clinical trials.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Sakula A. Paul Langerhans (1847–1888): a centenary tribute. J R Soc Med. 1988;81(7):414–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ceranowicz P, Cieszkowski J, Warzecha Z, Kusnierz-Cabala B, Dmbinski A. The beginnings of pancreatology as a field of experimental and clinical medicine. Biomed Res Int. 2015;20145:128095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ballinger W, Lacy P. Transplantation of intact pancreatic islets in rats. Surgery. 1972;72(2):175–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ris F, Niclauss N, Morel P, Demuylder-Mischler S, Muller Y, Meier R, Genevay M, Bosco D, Berney T. Islet autotransplantation after extended pancreatectomy for focal benign disease of the pancreas. Transplantation. 2011;91(8):895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buchwald P, Wang X, Khan A, Bernal A, Fraker C, Inverardi L, Ricordi C. Quantitative assessment of islet cell products: estimating the accuracy of the existing protocol and accounting for islet size distribution. Cell Transplantation. 2009;18(10):1223–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Linetsky E, Bottino R, Lehmann R, Alejandro R, Inverardi L, Ricordi C. Improved human islet isolation using a new enzyme blend, Liberase. Diabetes. 1997;46(7):1120–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pisania A, Papas K, Powers D, Rappel M, Omer A, Bonner-Weir S, GC W, Colton C. Enumeration of islets by nuclei counting and light microscopic analysis. Lab Invest. 2010;90(11):1676–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takei S, Teruya M, Grunewald A, Garcia R, Chan E, Charles M. Isolation and function of human and pig islets. Pancreas. 1994;9(2):150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim A, Miller K, Jo J, Kilimnik G, Wojcik P, Hara M. Islet architecture: a comparative study. Islets. 2009;1(2):129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Georges P, Muirhead R, Williams L, Holman S, Tabliln M, Dean S, Tuch B. Comparison of size, viability, and function of fetal pig islet-like cell clusters after digestion using collagenase or liberase. Cell Transplantation. 2002;11(6):539–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shimoda M, Noguchi H, Fujita Y, Takita M, Ikemoto T, Chujo D, Naziruddin B, Levy M, Kobayaski N, Grayburn PA, Matsumoto S. Islet purification method using large bottles effectively achieves high islet yield from pig pancreas. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(2–3):501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taylor M, Baicu S, Greene E, Vazquez A, Brassil J. Islet isolation from juvenile porcine pancreas after 24-h hypothermic machine perfusion preservation. Cell Transplant. 2010;19(5):613–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramachandran K, Huang H, Stehno-Bittel L. A simple method to replace islet equivalents for volume quantification of human islets. Cell Transplantation. 2015;24(7):1183–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buchwald P, Bernal A, Echeverri F, Tamayo-Garcia A, Linetsky E, Ricordi C. Fully automated islet cell counter (ICC) for the assessment of islet mass, purity, and size distribution by digital image analysis. Cell Transplantation. 2016;25(10):1747–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ionescu-Tirgoviste C, Gagniuc P, Gubceac E, Mardare L, Popescu I, Dima S, Militaru M. A 3D map of the islet routes throughout the healthy human pancreas. Scientific Rep. 2015;5:14634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suszynski T, Avgoustiniatos E, Papas K. Intraportal islet oxygenation. J. Diab Sci Tech. 2014;8(3):575–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaihoh T, Masuda T, Sasano N, Takahashi T. The size and number of Langerhans islets correlated with their endocrine function: a morphometry on immunostained serial sections of adult human pancreases. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 1986;149(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kilimnik G, Jo J, Periwal V, Zielinski M, Hara M. Quantification of islet size and architecture. Islets. 2012;4(2):167–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y, Danielson K, Ropski A, Harvat T, Barbaro B, Paushter D, Qi M, Oberholzer J. Systemic analysis of donor and isolation factor’s impact on human islet yield and size distribution. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(12):2323–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang H, Ramachandran K, Stehno-Bittel L. A replacement for islet equivalents with improved reliability and validity. Acta Diabetol. 2013;50(5):687–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li W, Zhao R, Liu J, Tian M, Lu Y, He T, Cheng M, Liang K, Li X, Wang X, Sun Y, Chen L. Small islet transplantation superiority to large ones: implications from islet microcirculation and revascularization. J Diabetes Res. 2014;2015:192093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. MacGregor R, Williams S, Tong P, Kover K, Moore W, Stehno-Bittel L. Small rat islets are superior to large islets in in vitro function and in transplantation outcomes. Am. J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E771–E779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nam K-H, Yong W, Harvat T, Adewola A, Wang S, Oberholzer J, Eddington D. Size-based separation and collection of mouse pancreatic islets for functional analysis. Biomed Microdevices. 2010;12(5):865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Su Z, Xia J, Shao W, Cui Y, Tai S, Ekberg H, Corbascio M, Chen J, Qi Z. Small islets are essential for successful intraportal transplantation in a diabetes mouse model. J Immunol. 2010;72:504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pathak S, Regmi S, Gupta B, Pham T, Yong C, Kim J, Yook S, Kim J, Park M, Bae YK, Jeong JH. Engineered islet cell clusters transplanted into subcutaneous space are superior to pancreatic islets in diabetes. FASEB. 2017;31(11):5111–5121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou Z-G, Gao X-H. Morphology of pancreatic microcirculation in the monkey: light and scanning electron microscopic study. Clin Anat. 1995;8(3):190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dufrane D, Goebbels R, Fdilat I, Guiot Y, Gianello P. Impact of porcine islet size on cellular structure and engraftment after transplantation. Pancreas. 2005;30(2):138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lembert N, Wesche J, Petersen P, Doser M, Becker HD, Ammon HP. Areal density measurement is a convenient method for the determination of porcine islet equivalents without counting and sizing individual islets. Cell Transplant. 2003;12(1):33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Woolcott O, Bergman R, Richey J, Kirkman E, Harrison L, Ionut V, Lottati M, Zheng D, Hsu I, Stefanovski D, Kabir M, Kim SP, Catalano KJ, Chiu JD, Chow RH. Simplified method to isolate highly pure canine pancreatic islets. Pancreas. 2012;41(1):31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vakhshiteh F, Allaudin Z, Mohd Lila M, Hani H. Size-related assessment on viability and insulin secretion of caprine islets in vitro. Xentotransplantation. 2013;20(2):82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Papas K, Colton C, Qipo A, Wu H, Nelson R, Hering B, GC W, Koulmanda M. Prediction of marginal mass required for successful islet transplantation. J. Invest Surgery. 2010;23(1):28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang L, Cochet O, Wang X, Krzystyniak A, Misawa R, Golab K, Tibudan M, Grose R, Savari O, Millis JM, Witkowski P. Donor height in combination with islet donor score improves pancreas donor selection for pancreatic islet isolation and transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2014;46(6):1972–1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Al-Adra D, Gill R, Imes S, O’Gorman D, Kin T, Axford S, Shi X, Senior P, Shapiro A. Single-donor islet transplantation and long-term insulin independence in select patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Transplantation. 2014;98(9):1007–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang X, Moore D, RJ K, Nunemaker C, Kovatchev B, McCall A, Brayman K. Resolving the conundrum of islet transplantation by linking metabolic dysregulation, inflammation, and immune regulation. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(5):603–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zorzi D, Phan T, Sequi M, Lin Y, Freeman D, Cicalese L, Rastellini C. Impact of size on pancreatic islet transplanation and potential interventions to improve outcome. Cell Transplantation. 2015;24(1):11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lehmann R, Zuellig R, Kugelmeier P, Baenninger P, Moritz W, A P, Clavien P, Weber M, Spinas G. Superiority of small islets in human islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2007;56(3):594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fujita Y, Takita M, Shimoda M, Itoh T, Sugimoto K, Noguchi H, Naziruddin B, Levy MF, Matsumoto S. Large human islets secrete less insulin per islet equivalent than smaller islets in vitro. Islets. 2011;3(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Suszynski T, Wilhelm J, Radosevich D, Balamurugan A, Sutherland D, Beilman G, TB D, Chinnakotla S, Pruett T, Vickers SM, Hering BJ, Papas KK, Bellin MD. Islet size index as a predictor of outcomes in clinical islet autotransplantation. Transplantation. 2014;97(12):1286–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Williams S, Huang H, Kover K, Moore W, Berkland C, Singh M, Smirnova I, MacGregor R, Stehno-Bittel L. Reduction of diffusion barriers in isolated rat islets improves survival, but not insulin secretion or transplantation outcome. Organogenesis. 2010;6(2):115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Farhat B, Almelkar A, Ramachandran K, Williams S, Huang H, Zamierowski D, Novikova L, Stehno-Bittel L. Small human islets comprised of more b-cells with higher insulin content than large. Islets. 2013;5(2):87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Petropavlovskaia M, Resenberg L. Identification and characterization of small cells in the adult pancreas: potential progenitor cells? Cell & Tissue Res. 2002;310(1):51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hansen W, Christie M, Kahn R, Norgaard A, Abel I, Petersen A, Jorgensen D, Baekkeskov S, Nielsen J, Lemmark A. Supravital dithizone staining in the isolation of human and rat pancreatic islets. Diabetes Res. 1989;10(2):53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ricordi C, Gray D, Hering B, Kaufman D, Warnock G, Kneteman N, Lake S, London N, Socci C, Alejandro R, Zeng Y, Scharp DW, Viviani G, Falqui L, Tzakis A, Bretzel RG, Federlin K, Pozza G, James RFL, Rajotte RV, Di Carlo V, Morris PJ, Sutherland DER, Startl TE, Mintz DH, Lacy PE. Islet isolation assessment in man and large animals. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1990;27(3):185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pisania A, Weir GC, O’Neil JJ, Omer A, Tchipashvili V, Lei J, Colton CK, Bonner-Weir S. Quantitative analysis of cell composition and purity of human pancreatic islet preparations. Lab Invest. 2010;90(11):1661–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ansite J, Balamurugan A, Barbaro B, Battle J, Brandhorst D, Cano J, Chen X, Deng S, Feddersen D, Friberg A, Gilmore T, Goldstein JS, Holbrook E, Khan A, Kin T, Lei J, Linetsky E, Liu C, Luo X, McElvaney K, Min Z, Moreno J, et al. Purified human pancreatic islet: qualitative and quantitive assessment of islets using dithizone (DTZ)-Standard operating procedure of the NIH Clinical Islet Transplantation Consortium. CellR4. 2015;3(1):e1369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ricordi C. Quantitative and qualitative standards for islet isolation assessment in humans and large mammals. Pancreas. 1991;6(2):242–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. D’Aleo V, Del Guerra S, Gualtierotti G, Filipponi F, Boggi U, De Simone P, Vistoli F, Del Prato S, Marchetti P, Lupi R. Functional and survival analysis of isolated human islets. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(6):2250–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fensom B, Harris C, Thompson S, Al Mehthel M, Thompson D. Islet cell transplantation improves nerve conduction velocity in type 1 diabetes compared to intensive medical therapy over six years. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;122:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lablanche S, Borot S, Wojtusciszyn A, Bayle F, Tétaz R, Badet L, Thivolet C, Morelon E, Frimat L, Penfornis A, Kessler L, Brault C, Colin C, Tauveron I, Bosco D, Berney T, Benhamou PY; GRAGIL Network. Five-year metabolic, functional, and safety results of patients with type 1 diabetes transplanted with allogenic islets within the Swiss-French GRAGIL network. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(9):1714–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lehmann R, Fernandez LA, Bottino R, Szabo S, Ricordi C, Alejandro R, Kenyon NS. Evaluation of islet isolation by a new automated method (Coulter Multisizer Ile) and manual counting. Transplant Proc. 1998;30(2):373–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Niclauss N, Bosco D, Morel P, Demuylder-Mischler S, Brault C, Milliat-Guittard L, Colin C, Parnaud G, Muller YD, Giovannoni L, Meier R, Toso C, Badet L, Benhamou PY, Berney T. Influence of donor age on islet isolation and transplantation outcome. Transplantation. 2011;91(3):360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ricordi C, Goldstein J, Balamurugan A, Szot G, Kin T, Liu C, Czarniecki C, Barbaro B, Bridges N, Cano J, Clarke WR, Eggerman TL, Hunsicker LG, Kaufman DB, Khan A, Lafontant DE, Linetsky E, Luo X, Markmann JF, Naji A, Korsgren O, Oberholzer J, et al. National Instittues of Health - sponsored clinical islet transplantation consortium phase 3 trial: manufacture of a complex cellular product in eight processing facilities. Diabetes. 2016;65(1):3418–3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. O’Gorman D, Kin T, Imes S, Pawlick R, Senior P, Shapiro AM. Comparison of human islet isolation outcomes using a new mammalian tissue-free enzyme versus collagenase NB-1. Transplantation. 2010;90(3):255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rawal S, Harrington S, Williams S, Ramachandran K, Stehno-Bittel L. Long-term cryopreservation of reaggregated pancreatic islets resulting in succesful transplantation in rats. Cryobiology. 2017;76:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rheinheimer J, Ziegelmann P, Carlessi R, Reck L, Bauer A, Leitão C, Crispim D. Different digestion enzymes used for human pancreatic islet isolation: a mixed treatment comparison (MTC) meta-analysis. Islets. 2014;6(4):e977118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Scharp D, Kemp C, Knight M, Ballinger W, Lacy P. The use of ficoll in the preparation of viable islets of langerhans from the rat pancreas. Transplantation. 1973;16(6):686–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kissler H, Niland J, Olack B, Ricordi C, Hering B, Naji A, Kandeel F, Oberholzer J, Fernandez L, Contreras J, Stiller T, Sowinski J, Kaufman DB. Validation of methodologies for quantifying isolated human islets: an islet cell resources study. Clin Transplant. 2009;24(2):236–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fetterhoff T, Wile K, Coffing D, Cavanagh T, Wright M. Quantitation of isolated pancreatic islets using imaging technology. Transplant Proc. 1994;26(6):3351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Niclauss N, Sgroi A, Morel P, Baertschiger R, Armanet M, Wojtusciszyn A, Parnaud G, Muller Y, Berney T, Bosco D. Computer-assisted digital image analysis to quantify the mass and purity of isolated human islets before transplantation. Transplantation. 2008;86(11):1603–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Avgoustiniatos E. Oxygen diffusion limitations in pancreatic islet culture and immunoisolation. Cambridge, UK: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Girman P, Berkova Z, Dobolilova E, Saudek F. How to use image analysis for islet counting. Rev Diabet Stud. 2008;5(1):38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jo J, Kilimnik G, Kim A, Guo C, Periwal V, Hara M. Formation of pancreatic islets involves coordinated expansion of small islets and fission of large interconnected islet-like structures. Biophys J. 2011;101(3):565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang X, Misawa R, Zielinski M, Cowen P, Jo J, Periwal V, Ricordi C, Khan A, Szust J, Shen J, Millis JM, Witkowski P, Hara M. Regional differences in islet distribution in the human pancreas-preferential beta-cell loss in the head region in patients with type 2 diabbetes. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Alanentalo T, Hornblad A, Mayans S, Karin Nilsson A, Sharpe J, Larefalk A, Ahlgren U, Holmberg D. Quantification and three-dimensional imaging of the insulitis-induced destruction of beta-cells in murine type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2010;59(7):1756–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kin T. Islet isolation for clinical transplantation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;654:683–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Girman P, Kriz J, Friedmansky J, Saudek F. Digital imaging as a possible approach in evaluation of islet yield. Cell Transplant. 2003;12(2):129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Stegemann JP, O’Neil JJ, Nicholson DT, Mullon CJ, Solomon BA. Automated counting and sizing of isolated porcine islets using digital image analysis. Transplant Proc. 1997;29(4):2272–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang L-J, Kissler H, Wang X, Cochet O, Krzystyniak A, Misawa R, Golab K, Tibudan M, Grzanka J, Savari O, Kaufman DB, Millis M, Witkowski P. Application of digital image analysis to determine pancreatic islet mass and purity in clinical islet isolation and transplantation. Cell Transplantation. 2015;24(7):1195–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wang L-J, Kaufman D. Digital image analysis to assess quantity and morphological quality of isolated pancreatic islets. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(7):1219–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Argibay P, Dalurzo M, Dorn V, Barbich M, Mongini C. Fully integrated optical microscope system and computer workstation system for standardized islet cell measurements and analysis. Transplant Proc. 1995;27(6):3347–3348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Habart D, Svihlik J, Schier J, Cahova M, Girman P, Zacharovova K, Berkova Z, Kruz J, Fabrryova E, Kosinova L, Papáčková Z, Kybic J, Saudek F. Automated analysis of microscopic images of isolated pancreatic. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(2):2145–2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jindal R, Taylor R, Gray D, Esmeraldo R, Morris P. A new method for quantification of islets by measurement of zinc content. Diabetes. 1992;41(9):1056–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Colton C, Paps K, Pisania A, Rappel M, DE P, O’Neil J, Omer A, Weir G, Bonner-Weir S. Characterization of islet preparation In: Halberstadt C, Emerich D, editors. Cellular transplantation: from laboratory to clinic. Volume 1 Burlington, MA: Elsevier; 2007. p. 85–134. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Beckmann J, Lenzen S, Holze S, Panten U. Quantification of cells in islets of Langerhans using DNA determination Acta Diabetol Lat. 1981;18(1):51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Detimary P, Dejonghe S, Ling Z, Pipeleers D, Schuit F, Henquin J-C. The changes in adenine nucleotides measured in glucose-stimulated rodent islets occur in β cells but not in α cells and are also observed in human islets. J Biol. Chem. 1998;273(51):33905–33908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Affourtit C, Brand M. Stronger control of ATP/ADP by proton leak in pancreatic b-cells than skeletal muscle mitochondria. Biochem J. 2006;393(1):151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Goto M, Holgersson J, BKumagai-Braesch M, Korsgren O. The ADP/ATP ratio: a novel predictive assay for quality assessment of isolated pancreatic islets. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(10):2483–2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ishii S, Sato Y, Terashima M, Saito T, Suzuki S, Murakami S, Gotoh M. A novel method for determination of ATP, ADP, and AMP contents of a single pancreatic islet before transplantation. Transpl Proc. 2004;36(4):1191–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Masini M, Anello M, Bugliani M, Marselli L, Fillipponi F, Boggi U, Purrelio F, Occhipinti M, Martino L, Marchetti P, De Tata V. Prevention by metformin of alterations induced by chronic exposure to high gluocse in human islet beta cells is associated with preserved ATP/ADP ratio. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;104(1):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nilsson T, Schultz V, Berggren P, Corkey B, Tornheim K. Temporal patterns of changes in ATP/ADP ratio, glucose- 6-phosphate and cytoplasmic free Ca2+ in glucose-stimulated pancreatic beta cells. Biochem J. 1996;314:91–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Suszynski T, Wildey G, Falde E, Cline G, Stewart Maynard K, Ko N, Sotiris J, Naji A, Hering B, Papas K. The ATP/DNA ratio is a better indicator of islet cell viability than the ADP/ATP ratio. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(2):346–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Papas K, Colton C, Nelson R, Rozak P, Avgoustiniatos E, Scott W, Wildey G, Pisania A, Weir G, Hering B. Human Islet Oxygen Consumption Rate and DNA Measurements Predict Diabetes Reversal in Nude Mice. Am. J Transplant. 2007;7(3):707–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Steurer W, Stadlmann S, Roberts K, Fischer M, Margreiter R, Gnaiger E. Quality assessment of isolated pancreatic rat islets by high-resolution respirometry. Transplant Proc. 1993;31(1-2):650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Chen C, Cohrs C, Stertmann J, Bozsak R, Speier S. Human beta cell mass and function in diabetes: recent advances in knowledge and technologies to understand disease pathogenesis. Mol Metab. 2017;6(9):943–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Fernandez LA, Hatch EW, Armann B, Odorico JS, Hullett DA, Sollinger HW, Hanson MS. Validation of large particle flow cytometry for the analysis and sorting of intact pancreatic islets. Transplantation. 2005;80(6):729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]