Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to (a) confirm the barriers to and facilitators of physical activity (PA) among persons living with chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Ontario and (b) inform the design of a Kidney Foundation of Canada Active Living for Life programme for persons living with CKD. Method: Adults living with CKD in Ontario were invited to participate in a cross-sectional survey investigating opinions about and needs for PA programming. The 32-item survey contained four sections: programme delivery preferences, current PA behaviour, determinants of PA, and demographics. Data were summarized using descriptive statistics and thematic coding. Results: A total of 63 respondents participated. They had a mean age of 56 (SD 16) years, were 50% female, and were 54% Caucasian; 66% had some post-secondary education. The most commonly reported total weekly PA was 90 minutes (range 0–1,050 minutes). Most respondents (84%) did not regularly perform strength training, and 73% reported having an interest in participating in a PA programme. Conclusion: Individuals living with CKD require resources to support and maintain a physically active lifestyle. We identified a diversity of needs, and they require a flexible and individualized inter-professional strategy that is responsive to the episodic changes in health status common in this population.

Key Words: community surveys, exercise, kidney diseases, , , , ,

Abstract

Objectif : la présente étude visait à a) confirmer les obstacles et les incitatifs à l'activité physique (AP) chez les personnes atteintes d'une néphropathie chronique (NPC) en Ontario et b) étayer la conception du programme Une vie active pour la vie de la Fondation canadienne du rein pour les personnes atteintes d'une NPC. Méthodologie : des adultes de l'Ontario atteints d'une NPC ont été invités à participer à un sondage transversal sur leurs avis et leurs besoins liés aux programmes d'AP. Le sondage de 32 questions était divisé en quatre parties : préférences quant à la prestation du programme, comportements actuels en matière d'AP, déterminants de l'AP et démographie. Les chercheurs ont résumé les données à l'aide de statistiques descriptives et de codes thématiques. Résultats : au total, 63 répondants ont participé. Ils avaient un âge moyen de 56 ans (ÉT de 16 ans), 50 % étaient des femmes, 54 % étaient blancs et 66 % avaient une certaine éducation postsecondaire. L'AP physique hebdomadaire totale la plus déclarée était de 90 minutes (plage de 0 à 1 050 minutes). La plupart des répondants (84 %) ne faisaient pas d'entraînement musculaire régulier, et 73 % se sont dit intéressés à participer à un programme d'AP. Conclusion : les personnes atteintes d'une NPC ont besoin de ressources pour maintenir un mode de vie actif. Les chercheurs ont repéré une diversité de besoins et la nécessité d'une stratégie interprofessionnelle personnalisée qui tient compte des changements épisodiques de l'état de santé, courants dans cette population.

Mots clés : exercice, néphropathies, sondages communautaires

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) carries with it several multi-system consequences, which can lead to impairments of “physical function, cognitive function, emotional functioning and quality of life.”1(p.305) The presence of complex comorbidity in CKD, particularly as patients age, can contribute to a heavy self-management burden.2 Evidence supports the use of therapeutic exercise and physical activity (PA) to improve several these negative consequences.3–7

Studies examining the barriers to and facilitators of PA and exercise among persons living with CKD have primarily focused on those living with end-stage kidney disease. For example, Delgado and Johansen8 studied patient-perceived barriers to engaging in 30 minutes of moderate-intensity PA among a cohort of 100 hemodialysis patients from a single dialysis unit in the United States. They identified 25 barriers to PA, with degrees of endorsement ranging from 1% (amputation) to 67% (fatigue on dialysis days). They also determined that fatigue, lack of motivation, and shortness of breath were commonly reported by patients in this dialysis unit, although only lack of motivation and shortness of breath were associated with the measured levels of PA. However, that study did not comment on possible other factors that might facilitate or enable PA. Furthermore, because the perception of benefits, drawbacks, and facilitators is linked to the level of PA referenced, these barriers and facilitators may vary, depending on the nature of PA defined, geographical location, and disease status (before dialysis vs. dialysis).

Calls to action have included exercise prescription to promote PA among persons living with CKD.9–12 However, high-quality evidence about how to best promote PA, either in the CKD population or in other populations, is lacking.13–15 This lack of evidence may account, in part, for the observed gap in PA promotion programmes targeted to persons living with CKD in Canada.16

The Kidney Foundation of Canada (KFOC) proposed to address this lack of programming by creating a physical literacy programme for persons living with CKD in Ontario.17 Called the Active Living for Life (KFOC-ALFL) programme, its intended goal was to help support people living with CKD to lead more active lives. To inform the development of the format (education, exercise) and content of the KFOC-ALFL, we conducted a patient needs assessment survey with the following objectives: (1) to confirm that previously reported barriers to and facilitators of PA participation among persons living with CKD were valid in the local context in which the KFOC-ALFL was to be piloted and (2) to inform the design of the content and delivery of, and evaluation strategies for, the KFOC-ALFL.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective, cross-sectional, voluntary survey of Ontario residents living with CKD.

Survey instrument

The principal investigator (TLP) developed a 32-item survey in consultation with the KFOC-ALFL Advisory Committee. This committee consisted of patient experience advisors, researchers, exercise professionals, and clinicians. The survey was based on a previous instrument developed by TLP and is grounded in the theory of planned behaviour.18 It was divided into four sections: (1) demographics (9 items), (2) current PA (9 items), (3) programme delivery preferences (10 items), and (4) psychosocial determinants of PA (4 items). Section 1 included open-text items to determine respondents' age, gender, ethnicity, preferred language, employment status, and highest education achieved.

Section 2 contained items to assess respondents' current level of weekly PA, including strength training. The “exercise vital sign” was used to capture the proportion of respondents who were not meeting PA guidelines (150–300 min/wk of moderate-intensity exercise).19 We asked respondents to identify the number of minutes per day (in 10 min intervals) they performed moderate-intensity exercise and the number of days per week they performed it. We also asked participants to report the degree to which they had access to exercise equipment, other programmes that supported their PA in their local communities, and any information or support they had already received from their nephrology team.

In section 3, we asked the participants to identify their information needs, both as open-text prompts and as closed checklists of 13 predefined topics related to PA and CKD (including balancing exercise and fatigue, developing a plan for PA, and balancing PA with a fear of falls). We asked participants to indicate the physical activities that they were interested in trying out or resuming. Additional items questioned their preferred travel distance (multiple choice, giving predefined distances), personal goals for PA participation (open text), and whether they would like to participate with a partner or spouse (multiple choice: yes, no, or unsure).

In section 4, we asked the respondents to answer four questions about a predefined level of at least 20 minutes of PA, performed three days a week at a moderate intensity.20 We chose this level of PA because it is the lowest level of PA recommended in the American College of Sports Medicine Guidelines for Exercise in Renal Disease21 and would represent a starting level of PA. In reference to this level of PA, we asked survey participants to identify the benefits, drawbacks, and facilitators of and barriers to performing the defined behaviour. The survey was pilot tested by three patient experience advisors serving on the KFOC-ALFL's Steering Committee. We incorporated their feedback into the final version of the survey.

Participants

We invited people living with CKD in Ontario to participate in the survey. To be included in the study, participants had to be aged older than 18 years, be community dwelling, have a current diagnosis of any stage of CKD, be fluent in English, and reside in Ontario. Recruitment for participation used two strategies: online and partnering with nephrology programmes in cities previously selected to pilot the KFOC-ALFL programme. The first recruitment strategy was to place an advertisement on the website of the Ontario branch of the KFOC; the ad included a link to the online version of the survey and the contact information of the KFOC-ALFL staff coordinator if an individual preferred to complete the survey in paper format. We also shared the online survey link through the Facebook page of KFOC's Ontario branch. The second strategy was to recruit participants through the nephrology programmes of sites identified to participate in the pilot programme. We gave these patients the option of completing the survey online, on paper, or over the telephone with a member of the investigative team.

All survey participants provided informed consent. The Queen's University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board and the ethics boards of the local institutions where paper surveys were distributed approved this study.

Analysis

We summarized responses using descriptive statistics for non-continuous and continuous data or thematic codes for open-text responses.

Results

Respondents

A total of 63 respondents (42 paper and 21 online) met the inclusion criteria for the study. They had, on average, a mean age of 56 (SD 16) years, and 50% were female (see Table 1). Respondents reported currently receiving a variety of renal replacement therapies; however, the majority (61%) were receiving in-centre hemodialysis. Although the largest proportion of respondents identified as Caucasian (54%), the balance consisted of respondents who identified as Arab/West Asian (2%), Japanese (2%), Filipino (2%), Chinese (4%), South Asian (5%), Black (7%), and other (18%). Approximately 66% of the survey respondents had received at least some post-secondary education. Employment status varied: 36% were retired, 24% were currently employed at some level, 5% were students, and 19% were receiving disability benefits. It is important to note that although we provided a “prefer not to answer” option for questions related to educational background, employment status, ethnicity, and household income, some data were missing (13%–16%) for these variables.

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Survey Participants (n=63)

| Characteristic | No. (%) of participants responding* |

| Mean age (SD), y† | 56 (16)* |

| Gender‡ | |

| Male | 30 (50) |

| Female | 30 (50) |

| Ethnicity§ | |

| Caucasian | 31 (54.4) |

| Other | 10 (17.5) |

| Black | 4 (7.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (7.0) |

| South Asian | 3 (5.3) |

| Chinese | 2 (3.5) |

| Arab/West Asian | 1 (1.8) |

| Japanese | 1 (1.8) |

| Filipino | 1 (1.8) |

| Language preference¶ | |

| English | 59 (95.2) |

| French | 1 (1.6) |

| Other | 2 (3.2) |

| Current treatment of kidney disease** | |

| In-centre hemodialysis | 35 (61.4) |

| Kidney transplant | 11 (19.3) |

| Home hemodialysis | 4 (7.0) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 4 (7.0) |

| Predialysis | 3 (5.3) |

| Highest education received†† | |

| Completed undergraduate degree | 16 (27.1) |

| Completed high school or equivalent | 12 (20.3) |

| Completed college diploma programme | 9 (15.3) |

| Completed graduate degree | 8 (13.6) |

| Some college or university credits (did not graduate) | 6 (10.2) |

| Some high school credits (did not graduate) | 4 (6.8) |

| Elementary school | 3 (5.1) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (1.7) |

| Current employment status‡‡§§ | |

| Retired | 21 (36.2) |

| Ontario Disability Support Program | 11 (19.0) |

| Not employed, but looking for work | 8 (13.8) |

| Not employed, not looking for work | 7 (12.1) |

| Employed full time | 6 (10.3) |

| Self-employed | 6 (10.3) |

| Student | 3 (5.2) |

| Employed part time | 2 (3.4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (3.4) |

| Homemaker | 1 (1.7) |

Note: Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

?*Unless otherwise indicated.

†n=61; ‡n=60; §n=57; ¶n=62; **n=57; ††n=59; ‡‡n=58; §§Participants could select more than one response.

Current level of physical activity

Of the respondents, 52 reported performing moderate-intensity PA, with a mean of 131 minutes per week. However, these results were not normally distributed (range 0–1,050 min/wk; median 90 min/wk; interquartile range 120 min/wk). Furthermore, 84% of the 61 respondents who answered this item indicated that they did not include strength training as part of their PA programme.

Only 48 participants responded to the question asking what information about PA they had received to date from their renal team; the majority reported either very little information (9%) or no information (48%). Among those who acknowledged receiving PA education from their renal team (9%), the most commonly reported message was to “walk and keep active.” Only 3% of the respondents reported receiving a specific prescription for exercise from their renal team. However, another 15% identified having received this information from a different resource, such as a cardiac rehabilitation centre, the local Community Care Access Program, or another community-based programme.

With respect to existing resources for PA, 48% of the respondents reported having access to exercise equipment, and 34% reported having access to existing programmes to help them become more physically active in their community. However, 26% reported being unsure of what resources existed in their local community.

A full 73% of the survey respondents indicated that they would be willing to participate in a programme designed to help them become more physically active if one were available to them. Roughly 37% indicated a willingness and ability to travel up to 20 minutes to attend a PA programme; another 38% were willing to travel up to 30 minutes, 10% up to 40 minutes, and 7% more than 40 minutes (see Table 2). Approximately 8% of the respondents were not able to travel at all to attend a programme.

Table 2.

Participants' Ability to Travel to Attend a Physical Activity Programme (n=60)

| Ability | % of participants |

| I am not able to travel | 8.3 |

| I am able to travel ≤20 min | 36.7 |

| I am able to travel 21–30 min | 38.3 |

| I am able to travel 31–40 min | 10.0 |

| I am able to travel >40 min | 6.7 |

Of the 13 educational topics, those with the highest proportion of respondent interest were “balancing PA and fatigue” (67%), “build a plan to be more physically active” (57%), “keeping motivated for PA” (57%), “nutrition and PA” (56%), “where do I start? Learn to measure what you are doing already and how to progress” (49%), and “how to find community resources to support you in being physically active” (46%). Approximately 10% of respondents reported that none of these topics was of interest. Respondents identified additional topics under “other”: how to get results when your body will not give you energy to go forward and exercise and arthritis.

Goals for physical activity participation

This item drew open-text responses from 47 participants. The most commonly identified goals for participation in PA programming were improving muscle strength (13%), increasing cardiorespiratory endurance or function (10%), losing weight (9%), increasing energy–decreasing fatigue (9%), and specific functional goals related to walking (9%). However, there was diversity in the personal goals identified by the survey respondents: We identified 21 individual thematic goals.

Finally, 59 participants responded to the item regarding the inclusion of a partner, spouse, friend, or caregiver in the KFOC-ALFL programme. Approximately 42% indicated that they would like to participate with a partner, 48% indicated that they would like to go on their own, and the remaining 10% were unsure.

Physical activity participation: benefits, drawbacks, facilitators, and barriers

Benefits

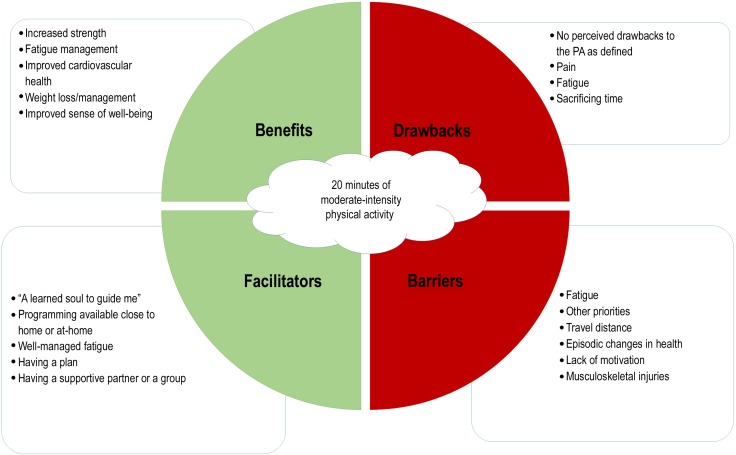

Fifty-four participants provided open-text responses to this item. The five most commonly identified perceived benefits of PA were increased strength (14%), management of fatigue (12%), improved cardiovascular health (11%), weight loss/management (11%), and improved overall sense of well-being (10%). There was significant heterogeneity in the responses. Other potential benefits were improved self-management of health (for, e.g., diabetes), better sleep, improved appetite, improved performance of activities of daily living, improved mental health, and improved resilience. Figure 1 summarizes the key themes that emerged.

Figure 1.

Key themes identified by the participants in relation to 20 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity: perceived benefits, drawbacks, facilitators, and barriers.

PA=physical activity.

Drawbacks

Fifty-one participants provided open-text responses to this item. Twenty-seven percent of respondents perceived no drawback to the PA as defined. Perceived drawbacks included pain (20%), fatigue (14%), sacrificing time (9%), increased falls risk (2%), and increased risk of cardiovascular events (4%). Roughly 12% of the respondents identified items that were barriers (e.g., lack of motivation) rather than drawbacks (e.g., exercise-induced pain or injury), suggesting that some respondents may not have understood this question clearly. It is also interesting to note that although a larger proportion of respondents perceived no risk or drawback to PA at the level defined in the survey,

Facilitators

Forty-eight participants provided open-text responses to this item. The most common perceived facilitators of performing the PA behaviour were “a learned soul to guide me” (8%), programming available close to home or at home (8%), well-managed fatigue (8%), having a plan (8%), and having a supportive partner or group (7%). A full 11% of the respondents reported that there were no facilitators of PA behaviour. We drew the code “a learned soul to guide me” from the response of one participant because it eloquently captured the complex facilitator identified by many participants. We defined the “learned soul to guide me” as an individual who was knowledgeable about exercise, knew the participant as a person and the person's health status, and could help them navigate the nuances of a complex and episodic health condition.

Barriers

Fifty-two participants provided open-text responses to this item. The most commonly perceived barriers to performing the PA behaviour at the defined level were fatigue (14%), other priorities or distractions (11%), travel distance to the programme (7%), episodic changes in health status or acute illness (5%), lack of motivation (5%), and the presence of musculoskeletal injuries (5%). Eleven percent of the respondents reported that they perceived no barriers to performing the PA behaviour.

Discussion

This cross-sectional survey reveals important gaps in PA promotion and programming for individuals living with CKD and highlights the diversity of their needs for PA programming. These gaps are the limited PA promotion and services available through renal programmes, the absence of routine strength training by participants despite achieving recommended levels of aerobic activity, and limited access to or knowledge of existing PA programmes in local communities (delivered through either formal rehabilitation or community wellness programmes). This patient-reported lack of PA and services from renal programmes is consistent with the literature on the availability of programmes and exercise counselling activities of renal teams from Canada,16 the United States,22 and the United Kingdom.23 It is interesting to note that some respondents are receiving their information from elsewhere—that is, from other community and rehabilitation programmes; this speaks, in part, to the complexity of living with the medical condition that is CKD. In other words, because of coexisting impairments in their cardiorespiratory, neurological, or musculoskeletal systems, these patients may have been referred to other programmes and services for information and support (e.g., cardiac rehabilitation, outpatient physiotherapy).

On the basis of the educational topics of interest that were identified through the survey, there is a need for health care teams to offer better management strategies of the symptoms of people living with CKD (especially fatigue), comorbid conditions (e.g., arthritis), and information on PA planning and initiation. Respondents identified a wide diversity of goals and PA interests. Although this was expected, these results emphasize the need for a programme that is flexible enough to align patients' goals with the intervention to achieve results that will encourage and motivate them in the long term. Certainly, no single recipe for exercise prescription can adequately address this diversity.

The respondents identified several benefits, including improved strength, lower fatigue, and better cardiovascular health, associated with an initial level of PA, whereas the drawbacks related primarily to pain, fatigue, and lost time. Facilitators included a “learned soul to guide me,” a programme that was either close to or at home, having a plan, and having a supportive partner or group. Symptoms related to respondents' health status (arthritis, shortness of breath, pain, fatigue) were the most commonly identified barriers. Rehabilitation interventions, including but not limited to therapeutic exercise prescription, may help address some of these issues.24–31 Other barriers included the episodic nature of respondents' health, travel distance, lack of motivation, and time.

Other authors have investigated the barriers to and facilitators of PA in CKD in populations outside Canada. Delgado and Johansen8 identified fatigue, lack of motivation, and shortness of breath as common patient-reported barriers to PA; however, only lack of motivation and shortness of breath were associated with the measured PA. Fatigue and lack of motivation were also commonly reported by the sample of respondents in the current study; this is interesting because respondents were asked to reflect on the barriers to a relatively lower amount of weekly exercise. Zelle and colleagues32 identified low physical self-efficacy and fear of movement as barriers to PA among persons after kidney transplantation. Among patients undergoing routine hemodialysis, previously reported barriers to leisure time PA have included lower levels of PA as an adult before the start of the treatment, having diabetes or hypertension as the cause of kidney failure, and the presence of cardiovascular disease.33 Our findings are consistent with these in that our respondents identified unmanaged comorbid conditions as potential barriers, but they expanded the list of barriers to include pain and other musculoskeletal conditions.

Finally, a qualitative study from the United Kingdom reported that motivators for exercise included family support, goal setting, and the accessibility of local facilities; barriers to exercise included “poor health, fear of injury or aggravating their condition, a lack of guidance from healthcare professionals and a lack of facilities.”34(p.1885) Although respondents in the current study echoed some of these elements, only a minority of respondents identified fear of injury. Respondents identified fatigue and travel distance as more common barriers.

One limitation of this small and voluntary survey was that its results were subject to selection bias; thus, they may not reflect the overall population with CKD in Canada because non–English speakers, certain ethnic groups, and those who are not literate were absent or under-represented. Nonetheless, our results provide some direction for the design, implementation, and evaluation of pilot PA programmes for CKD; these can be modified for subpopulations as future evaluations deem necessary.

There is an ongoing need to provide evidence-based resources to support the maintenance of a physically active lifestyle among persons living with CKD in Ontario. The diversity of identified needs requires an integrated and flexible strategy, founded on the participants' goals and preferences, that takes into account the episodic nature of acute illness and fluctuating health status as well as the social factors that disproportionately affect this population. Given the physical barriers to PA (including pain, fatigue, shortness of breath, and musculoskeletal injuries), a programme that facilitates movement system diagnosis and the identification of individuals in need of formal rehabilitation (e.g., cardiac, geriatric, musculoskeletal, and pulmonary) is recommended to ensure that the right care is provided at the right time.

Furthermore, of chief importance to the respondents was that they had “a learned soul to guide them,” an individual who was knowledgeable about exercise, who knew the participant as a person and his or her health status, and who could help the person navigate the nuances of a complex and episodic health condition. Given the diversity of educational needs and goals identified by the respondents, PA programmes are also recommended to use a model of inter-professional practice and education—including nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, kinesiology, pharmacology, social work, psychology, and medicine—that collaborates with or is part of the renal care team. Finally, we advise that programmes enable patients to pursue their preferred PA either close to home or at home, be flexible enough to include a family member or partner through partnerships with existing community wellness resources, and develop other solutions with these goals in mind.

Conclusion

The results of this needs assessment survey demonstrate that, even at the lowest level of recommended PA in the current guidelines for CKD, the respondents commonly identify physical symptoms (including fatigue and pain) as a barrier to participation. When designing a physical literacy programme, these key elements should be considered: It should include access to a knowledgeable facilitator, incorporate strength training, be individualized to a patient's health status and goals, and be provided close to home. Further work should confirm these findings in groups underrepresented in the current study sample.

Key Messages

What is already known about this topic

Physical inactivity is prevalent among persons living with chronic kidney disease (CKD), and it contributes to their lower health status and quality of life. Adhering to lifestyle interventions is also low.

What this study adds

A description of the scope of need for physical activity (PA) programmes for persons living with CKD in Ontario was completed. Information from this survey about patients' preferences, attitudes, perceptions, and summary recommendations will help to inform the design, delivery, and evaluation of PA programmes for persons living with CKD. Incorporating patients' perspectives and preferences into the design, implementation, and evaluation of future PA programmes is imperative.

References

- 1. Kittiskulnam P, Sheshadri A, Johansen KL.. Consequences of CKD on functioning. Semin Nephrol. 2016;36(4):305–18. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.05.007. Medline:27475661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fraser SD, Taal MW.. Multimorbidity in people with chronic kidney disease: implications for outcomes and treatment. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2016;25(6):465–72. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000270. Medline:27490909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heiwe S, Jacobson SH.. Exercise training for adults with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(10):CD003236 10.1002/14651858.CD003236.pub2. Medline:21975737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parsons TL, King-Vanvlack CE.. Exercise and end-stage kidney disease: functional exercise capacity and cardiovascular outcomes. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009;16(6):459–81. 10.1053/j.ackd.2009.08.009. Medline:19801136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koufaki P, Greenwood SA, Macdougall IC, et al. Exercise therapy in individuals with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and synthesis of the research evidence. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2013;31(1):235–75. 10.1891/0739-6686.31.235. Medline:24894142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sawant A, House AA, Overend TJ.. Anabolic effect of exercise training in people with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Physiother Can. 2014;66(1):44–53. 10.3138/ptc.2012-59. Medline:24719508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barcellos FC, Santos IS, Umpierre D, et al. Effects of exercise in the whole spectrum of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(6):753–65. 10.1093/ckj/sfv099. Medline:26613036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delgado C, Johansen KL.. Barriers to exercise participation among dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(3):1152–7. 10.1093/ndt/gfr404. Medline:21795245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Howden EJ, Coombes JS, Strand H, et al. Exercise training in CKD: efficacy, adherence, and safety. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(4):583–91. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.017. Medline:25458662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koufaki P, Greenwood S, Painter P, et al. The BASES expert statement on exercise therapy for people with chronic kidney disease. J Sports Sci. 2015;33(18):1902–7. 10.1080/02640414.2015.1017733. Medline:25805155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Howden EJ, Coombes JS, Isbel NM.. The role of exercise training in the management of chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24(6):480–7. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000165. Medline:26447795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilkinson TJ, Shur NF, Smith AC.. “Exercise as medicine” in chronic kidney disease. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(8):985–8. 10.1111/sms.12714. Medline:27334146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freak-Poli RL, Cumpston M, Peeters A, et al. Workplace pedometer interventions for increasing physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(4):CD009209 10.1002/14651858.CD009209.pub2. Medline:23633368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baker PR, Francis DP, Soares J, et al. Community wide interventions for increasing physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD008366 10.1002/14651858.CD008366.pub3. Medline:25556970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richards J, Thorogood M, Hillsdon M, et al. Face-to-face versus remote and web 2.0 interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD010393 10.1002/14651858.CD010393.pub2. Medline:24085593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ma S, Lui J, Brooks D, et al. The availability of exercise rehabilitation programs in hemodialysis centres in Ontario. CANNT J. 2012;22(4):26–32. Medline:23413536 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kidney Foundation of Canada. Active living for life program [Internet]. Mississauga (ON): The Foundation; [cited 2016 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.kidney.ca/on/activeliving [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eng JJ, Martin Ginis KA.. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict leisure time physical activity among people with chronic kidney disease. Rehabil Psychol. 2007;52(4):435–42. 10.1037/0090-5550.52.4.435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, et al. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(11):2071–6. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182630ec1. Medline:22688832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johansen KL, Painter P.. Exercise in individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(1):126–34. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.008. Medline:22113127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 9th ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2013. p. 307–9 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johansen KL, Sakkas GK, Doyle J, et al. Exercise counseling practices among nephrologists caring for patients on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(1):171–8. 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50001. Medline:12500234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greenwood SA, Koufaki P, Rush R, et al. Exercise counselling practices for patients with chronic kidney disease in the UK: a renal multidisciplinary team perspective. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;128(1–2):67–72. 10.1159/000363453. Medline:25358965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, et al. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD004376. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004376.pub3. Medline:25569281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang WD, Chen S, Lee CL, et al. The effects of tai chi chuan on improving mind-body health for knee osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:1813979 10.1155/2016/1813979. Medline:27635148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson LJ, Taylor RS.. Cardiac rehabilitation for people with heart disease: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(2):348–61. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.011. Medline:25456575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Desveaux L, Lee A, Goldstein R, et al. Yoga in the management of chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Care. 2015;53(7):653–61. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000372. Medline:26035042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Vilsteren MC, de Greef MH, Huisman RM.. The effects of a low-to-moderate intensity pre-conditioning exercise programme linked with exercise counselling for sedentary haemodialysis patients in the Netherlands: results of a randomized clinical trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(1):141–6. 10.1093/ndt/gfh560. Medline:15522901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yurtkuran M, Alp A, Yurtkuran M, et al. A modified yoga-based exercise program in hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled study. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15(3):164–71. 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.06.008. Medline:17709061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang Y, Cheng SY, Lin M, et al. The effectiveness of intradialytic leg ergometry exercise for improving sedentary life style and fatigue among patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(11):1383–8. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.05.002. Medline:20537645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pianta TF. The role of physical therapy in improving physical functioning of renal patients. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1999;6(2):149–58. 10.1016/S1073-4449(99)70033-6. Medline:10230882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zelle DM, Corpeleijn E, Klaassen G, et al. Fear of movement and low self-efficacy are important barriers in physical activity after renal transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0147609 10.1371/journal.pone.0147609. Medline:26844883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosa CS, Bueno DR, Souza GD, et al. Factors associated with leisure-time physical activity among patients undergoing hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(1):192 10.1186/s12882-015-0183-5. Medline:26613791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clarke AL, Young HM, Hull KL, et al. Motivations and barriers to exercise in chronic kidney disease: a qualitative study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(11):1885–92. 10.1093/ndt/gfv208. Medline:26056174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]