Abstract

Preterm Birth (PTB) accounts for approximately 11% of all births worldwide each year and is a profound physiological stressor in early life. The burden of neuropsychiatric and developmental impairment is high, with severity and prevalence correlated with gestational age at delivery. PTB is a major risk factor for the development of cerebral palsy, lower educational attainment and deficits in cognitive functioning, and individuals born preterm have higher rates of schizophrenia, autistic spectrum disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Factors such as gestational age at birth, systemic inflammation, respiratory morbidity, sub-optimal nutrition, and genetic vulnerability are associated with poor outcome after preterm birth, but the mechanisms linking these factors to adverse long term outcome are poorly understood. One potential mechanism linking PTB with neurodevelopmental effects is changes in the epigenome. Epigenetic processes can be defined as those leading to altered gene expression in the absence of a change in the underlying DNA sequence and include DNA methylation/hydroxymethylation and histone modifications. Such epigenetic modifications may be susceptible to environmental stimuli, and changes may persist long after the stimulus has ceased, providing a mechanism to explain the long-term consequences of acute exposures in early life. Many factors such as inflammation, fluctuating oxygenation and excitotoxicity which are known factors in PTB related brain injury, have also been implicated in epigenetic dysfunction. In this review, we will discuss the potential role of epigenetic dysregulation in mediating the effects of PTB on neurodevelopmental outcome, with specific emphasis on DNA methylation and the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase family of enzymes.

Keywords: Preterm birth, Neurodevelopmental disorders, Epigenetic, DNA methylation, Epigenetic dysregulation, α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase

1. INTRODUCTION

Preterm Birth (PTB) is clinically defined as birth prior to 37 weeks of gestation [1]. In 2010, PTB accounted for 11.1% of all live births reported worldwide, with complications directly resulting from PTB accounting for approximately 1 million deaths per year [2]. Seventy five percent of all deaths in the perinatal period occur among those born preterm [3] and in 2013 infant mortality in England and Wales was 1.4 and 21.1 per 1000 live births for term and preterm births respectively [4] and a similar relationship is thought to exist in the U.S [5].

In recent decades, the mortality associated with PTB has decreased with improved neonatal care, and although this was initially accompanied by an increase in the prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders within the surviving PTB population [6, 7], neurodevelopmental outcomes for those born preterm have improved since the 1990’s, possibly as a consequence of the decreased use of post-natal glucocorticoids [8]. Nevertheless, PTB remains the single largest risk factor for poor long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in childhood [9] and is associated with an increased prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders including Cerebral Palsy [10], Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) [11] and Schizophrenia [12]. PTB is also predictive of cognitive score at school age, with younger gestational ages typically receiving lower scores [13]. In this review, we outline the neurodevelopmental consequences of PTB and the mechanisms that have been identified which might account for them. We focus on the potential role of epigenetic dysregulation in mediating short and long term consequences of PTB on the developing brain, concentrating on DNA methylation and the role of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase family.

2. NEURODEVELOPMENTAL CONSEQUENCES OF PTB

2.1. Cerebral Palsy (CP)

CP describes “a group of disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation, that are attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain. The motor disorders of cerebral palsy are often accompanied by disturbances of sensation, cognition, communication, perception, and/or behaviour, and/or by a seizure disorder” [14]. The disturbances to brain structure and function that underlie CP are highly varied, but PVL (Periventricular Leukomalacia) and diffuse white matter injury are frequent features [15]. PVL consists of focal necrotic regions deep in the white matter consisting of both glia and neurons [16]. It is estimated that 2-3.5/1000 neonates will go on to develop CP [17] and PTB is a major risk factor. In the EPICure study of those born extremely preterm (less than 26 weeks) in the UK and Ireland, the incidence of CP was inversely proportional to gestational age [18]. The mechanism underlying CP and white matter injury are varied and this is reflected in the range of associated comorbidities such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia [19], intrauterine growth restriction [20], necrotising enterocolitis [21] and chorioamnionitis [22, 23].

2.2. ADHD and Attention Difficulties

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder with a worldwide incidence of 5.3% and is the most common childhood psychiatric disease [24]. ADHD is thought to arise as a consequence of altered connectivity and neuronal network specific dysfunction [25] and risk factors include prenatal exposure to recreational drugs [26], as well as being born small for gestational age, low birth weight, small head circumference and PTB [27]. In a large Swedish cohort, individuals born preterm had an increased incidence of ADHD, with the prevalence increasing among those born earlier [28] and these results have subsequently been replicated in smaller cohorts from Italy [29] and Taiwan [30]. The symptoms of ADHD associated with PTB are more heavily weighted towards attention abnormalities than in ADHD not associated with PTB [31].

2.3. Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD)

ASD diagnoses have increased in the last 50 years [32], likely as a consequence of broadening diagnostic criteria and increased symptomatic recognition. Although ASDs can be broadly defined as consistent difficulties in both verbal and non-verbal social interactions [33], they are highly heterogeneous in their etiology, phenotype and severity and this is reflected in the DSM V criteria for ASD diagnosis, with three levels of severity and several syndromic and non-syndromic forms described [33]. There is a higher prevalence of ASD in males [34], with a prevalence amongst 8-year old boys and girls in the UK of 3.8 and 0.8 per 1000 respectively [35].

Although genetic risk factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of many syndromic and non-syndromic forms of ASD [36], which occur for example in association with Rett syndrome, Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) and with mutations in the Jumonji Domain Containing Histone Demethylase (JMJD1C) (a member of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase family) [37], epidemiological studies have shown that environmental factors such as PTB and its associated insults are also significant risk factors for the development of ASD [38]. Additionally, perinatal infection has been linked to ASD, for example in the large CHARGE (Childhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment) study, maternal influenza was specifically associated with an increased ASD incidence in offspring [39]. An increase in inflammatory markers in utero are also associated with an increased risk of ASD [40] and a non-age matched study of post-mortem tissue showed increased microglial activation within the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex of males diagnosed with ASD [41]. The male bias in ASD may indicate an underlying mechanistic causation for androgens in ASD pathogenesis, indeed testosterone exposure during critical periods in utero has been shown to be crucial to brain development and has been linked with ASD development [42].

2.4. Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia has a prevalence in the general population of around 5 per 1000 [43] and is thought to have developmental origins. There is an increased prevalence of schizophrenia amongst individuals born preterm [12]. Although the etiology of schizophrenia remains elusive, many factors implicated in the pathophysiology of PTB are also implicated in schizophrenia. Notably, infection and inflammation may play a role: maternal infection, in particular influenza [44] and increased levels of maternal circulating cytokines have been associated with an increased risk of schizophrenia development in offspring [45]. Although the mechanisms linking maternal infection and/or inflammation with the development of schizophrenia remain unclear, studies suggest a reallocation of resources available to the fetus in response to maternal infection may be important [46].

The results of an analysis of publicly available Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) for schizophrenia by Goudriaan et al. suggests dysregulation of cell specific genes in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes may at least partially mediate the schizophrenia phenotype [47]. In the perinatal period following PTB, oligodendrocytes are thought to be particularly vulnerable to injury and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of hypoxic brain injury associated with PTB [48] and astrocytes may at least partially mitigate the excitotoxic insults associated with PTB [49]. In a review of the available schizophrenia GWAS, Schmidt-Kastner et al. demonstrated that 55% of genes associated with schizophrenia onset have also been linked to fetal hypoxia response mechanisms [50], a mechanism implicated in PTB related brain injury which will be discussed in more detail later.

3. THE POTENTIAL ROLE OF GLUCOCORTICOID EXPOSURE

Synthetic glucocorticoids are routinely administered to pregnant women at risk of delivering prematurely [51] because they reduce death, respiratory distress syndrome and intraventricular haemorrhage in preterm infants [52], and are safe for mothers [52, 53]. They readily diffuse across the placenta [54] and act to accelerate fetal organ maturation, particularly the lungs. When administered antenatally, the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone has been shown to decrease brain infarct size in a dose-dependent manner [55], however other studies have reported a decrease in hippocampal neuronal density in post mortem human tissue (mean age 27 weeks) following glucocorticoid exposure [56]. Despite this, antenatal glucocorticoid administration was found to have no correlation with later IQ [57]. Glucocorticoids have the ability to block glucose uptake into neurons and glia [58], and within the context of neonatal brain injury, this may be neuroprotective, for example in studies in piglets, increased blood glucose levels potentiate the effects of Hypoxia/Ischemia (HI) through increased lactate production [59]. Several animal studies also suggest that glucocorticoids may have deleterious effects. The use of betamethasone (another synthetic glucocorticoid) in a PTB sheep model leads to decreased cerebral blood flow, an increased glycolytic response and a decrease in the mature oligodendrocyte population [60], and dexamethasone exposure reduced expression of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (a glutamate receptor) in sheep [61]. In rodent models, glucocorticoids have a well-established correlation with reduced birth weight [62] but this was not seen in a non-human primate model [63]. In mice, where within the cerebellum there is selective expression of the glucocorticoid receptor in the external granule layer, glucocorticoid exposure resulted in an increased level of caspase 3 activation [64]. In this study, caspase 3 staining localized with Ki-67, implying progenitors are susceptible to apoptosis in the cerebellum after glucocorticoid administration [64]. This may be an underlying cause for the decreased cerebellar volume reported on MRI examination of individuals born preterm who had been exposed to postnatal glucocorticoids [65].

The use of early postnatal glucocorticoids in high dose has been cautioned against [66] because of the association with increased incidence of cerebral palsy and other neurodevelopmental disorders as reviewed by Barrington [67]. However, there remain uncertainties about use of postnatal glucocorticoids for ventilator-dependent preterm infants, who may stand to benefit from earlier extubation without apparent long term morbidity [68, 69]. In animal models, behavioral abnormalities have been seen following post-natal glucocorticoid administration, with an increase in a depression-like phenotype reported in rats [70] as well as decreased levels of activity and an altered stress response in adolescent rats (P33) [71]. Although postnatal glucocorticoid administration has been associated with clear adverse consequences [67], improved outcomes have been reported with low dose post-natal administration in cases of extreme PTB [69]. There seems to be an undefined time before which glucocorticoid treatment is beneficial and after which glucocorticoid treatment is detrimental.

4. SEXUAL DIMORPHISM IN PTB-ASSOCIATED DISEASE RISK

There are differences in outcome between males and females born preterm, with males having a higher incidence of most neurodevelopmental disorders following PTB [72]. Cortical growth and scaling has also been shown to be disrupted by PTB in a sexually dimorphic manner [73]. There is some evidence to suggest that these differences may be mediated through sex-specific inflammatory responses to PTB. Using dissociated astrocyte cultures from neonatal mice, Santos-Galindo et al. demonstrated significantly different cytokine expression between male, androgenized female and female astrocytes in response to a Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulus [74]. Potential protective factors in females include early cell proliferation in the hippocampus following neonatal hypoxia-ischaemia which, exceeds that in males [75], and female mice have 25-40% more microglia than their male counterparts early in life [76], which demonstrates an early imbalance in resource allocation which may be involved in altered inflammatory responses in neonatal brain injury. In male rats, there is specific disruption of early Purkinje cell development in response to inflammation [77] and following hypoxia-ischemia, male rats show increased ubiquitination of mitochondria and mitophagy in the cortex, in association with impaired expression of electron transport proteins [78, 79]. Since mitochondria play an integral role in the cellular response to hypoxia, these male specific deficiencies could be important in the sex-specific responses to hypoxia [80]. Using circulating blood samples from pregnant human females, Mitchell et al. recently reported an increased maternal cytokine release upon LPS stimulus of immune cells, when pregnant with a female rather than a male fetus. These results imply a mechanism whereby the sex of the fetus may sensitize the maternal immune system to an increased inflammatory response [81]. In clinical trials the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug Indomethacin was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of intraventricular hemorrhage when administered to boys born preterm but had no such effect in girls [82, 83]. Some of these sex differences may be propagated through epigenetic mechanisms since it has long been known that sex hormones have the potential to alter the epigenome [84, 85] and male/female methylomes differ significantly at many loci throughout development [86, 87].

5. EPIGENETIC MODIFICATIONS

Many different definitions of the term “epigenetics” exist, and Adrian Bird’s definition of “the structural adaptation of chromosomal regions so as to register, signal or perpetuate altered activity states” [88] is one of the more commonly used modern definitions. For this review, we will primarily focus on the role of DNA cytosine modifications, as well as the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase family of enzymes.

5.1. DNA Methylation

DNA methylation typically occurs at the 5’ carbon of cytosine residues, usually when accompanied by a guanine residue in the sequence Cytosine-phosphate-Guanine (CpG) [89], to produce 5-methylcytosine (5mC). Genome wide, roughly 10% of CpG sites are present in clusters called CpG Islands (CGI), which are often located in the promoter regions of key developmentally regulated genes [89]. Although CGIs are generally unmethylated, the presence of 5mC in these areas is typically associated with repression of gene transcription [90]. DNA methylation is highly conserved from plants to mammals and is widely viewed as a key mechanism in the fine spatial and temporal control of gene expression during development [89]. Low levels of 5mC are generally associated with pluripotency, where less than 30% of CpGs may be methylated as opposed to terminally differentiated cells where up to 85% of CpGs may be methylated [91]. The DNA methyltransferase enzymes DNMT3A and 3B are responsible for de novo DNA methylation [92], while DNMT1 is responsible for maintaining the methylation of the complimentary strand during DNA replication [93].

The Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) enzymes were first proposed to generate 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) from 5mC by Tahiliani et al. [94]. The three TET proteins (TET1-3) are part of a large group of α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase enzymes which also comprises other epigenetic modifiers such as the JMJD1C histone demethylases and the proline hydroxylase (PHD) proteins, (which are involved in the cellular response to hypoxia [95]). This group of enzymes are dependent on the TCA cycle metabolite α-ketoglutarate and oxygen as essential substrates and Fe2+ as an essential co-factor [96]. TET1 and TET2 have overlapping functions [97], a level of redundancy that reflects their biological importance, whilst TET3 is thought to be important during reprogramming within the oocyte [98] although it has recently been shown to be important at later developmental stages within the retina [99]. The TET enzymes can be regulated at multiple levels, including through DNA methylation at the TET1 and TET2 promoters [100, 101], through the action of transcription factors such as HIF1β [102], and through regulation at the mRNA and protein level [103-107]. The TET enzymes are therefore highly responsive to environmental stimuli, which perhaps plays a role in their dynamic developmental role.

The dynamics of 5mC and 5hmC vary throughout development in rodents and humans [86]. A gradual increase in 5hmC is seen at developmentally primed genes in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) as well as in mice at postnatal day (P)7 [108]. 5hmC levels increase in tandem with cerebellar growth and development, with specific enrichment at genes controlled by FMRP (Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein) [109]. In mouse ESCs, 5hmC is found intragenically at genes which are actively transcribed and at extended promoters of polycomb repressed genes, distinct functions which are due to TET1 interactions with the histone mark H3K4me3 (which is associated with transcriptional activation) or H3K6me3 (associated with transcriptional repression) [110]. In the adult brain, 5hmC is present throughout gene bodies at much higher levels than in ESCs and for the most part is absent at Transcription Start Sites (TSS), where 5hmC is typically enriched in ESCs [108]. The view of 5hmC as a stable epigenetic modification would imply that there should be mechanisms in place by which the cell can recognize and respond to the presence of 5hmC. These so called ‘5hmC readers’ have been elusive, with only a handful being characterized to date. Spruijt et al. [111] identified the SRA group of the UHRF2 complex as being able to bind 5hmC and recruit other complexes, while Mellen et al. demonstrated that MeCP2 can bind to 5hmC with high affinity [112]. There is also evidence to suggest that 5fC and 5caC act as distinct epigenetic marks and have effects on gene transcription [113], although research has been somewhat limited because of their relative sparsity in the genome compared to 5mC/5hmC. Thus, since the TET enzymes control transitions between these epigenetic states, alterations of these states through altered TET function could have severe consequences during neonatal brain injury.

5.2. Histone Modifications

Histones control the accessibility to DNA of transcription factors and epigenetic readers [114]. They are subject to a plethora of post-translational modifications including, but not limited to, acetylation, methylation and phosphorylation [115] and these modifications are integral for transcriptional regulation [116]. A group of histone demethylases, including the JMJD1C histone demethylases are part of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase family [117]. Factors that are implicated in TET dysfunction therefore also have the potential to influence gene expression through histone modifications.

6. THE ROLE OF THE EPIGENOME IN NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

Several neurodevelopmental disorders are associated with alterations in the epigenome, particularly DNA methylation. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations of the DNA methylation reader MECP2 [118]; ICF (Immunodeficiency, Centromeric region instability, Facial anomalies) syndrome is associated with a mutation in the de novo DNA methyltransferase DNMT3b [119]; and FXS is associated with an expanded CGG repeat in the promoter of the FMRP gene, which results in its hypermethylation and subsequent silencing [120]. The imprinting disorders Angelman syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome are caused in most cases by abnormalities within imprinted gene regions, as reviewed by Rangasamy et al. 2013 [121]. While these syndromic forms of neurodevelopmental disorders can be classified by their known etiology and characteristic symptoms, the etiology of non-syndromic neurodevelopmental disorders is often unknown and there is a large symptomatic overlap between disorders, with central diagnostic criteria such as low IQ and social difficulties listed for many disorders [122] leading to levels of diagnostic imprecision so that patients may have multiple different diagnoses [123].

6.1. Schizophrenia

There is growing evidence that epigenetic dysregulation plays a central role in schizophrenia. Using a genome wide approach to analyse epigenetic alterations in post-mortem prefrontal cortical tissue from patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, Mill et al. showed DNA methylation alterations within glutamatergic and GABAergic signaling pathways, and at genes associated with brain development (N=35 and mean age of 41-45 for all categories) [124]. A genome wide study of DNA methylation on post mortem tissue from schizophrenia patients showed differential methylation at various key epigenetic regulators such as DNMT1, and a high level of clustering within schizophrenia patients and controls implying widespread and distinct alterations in the methylome in schizophrenia [125]. DNMT1 has been shown to be overexpressed in the prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, specifically in layer I GABAergic interneurons [126]. This overexpression was correlated with a decreased presence of GAD67 (glutamic acid decarboxylase) and reelin, also within layer I of the prefrontal cortex, as a consequence of hypermethylation of their promoters [126]. Decreased levels of GAD65 and GAD67 have also been reported in the hippocampus [127] of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

There is mounting evidence for dysregulation of histone modifying enzymes and histone modifications in schizophrenia. In a GWAS focusing on Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with schizophrenia, Shi et al. identified a key chromosomal area, 6p22.1, in which SNPs associated with histone modifiers were associated with schizophrenia [128]. Upregulation of the histone deacetylase (HDAC1) has been reported in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients and upregulation of HDAC2 occurs in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [129]. Tang et al. also showed age dependent alterations in the acetylated histone mark ac-H3K14, with controls showing a declining histone acetylation trajectory through life whilst patients with schizophrenia showed consistently low levels across all ages [130]. There is also some evidence for altered histone methylation in a subset of patients with schizophrenia [131].

6.2. ADHD

As noted by Franke et al. [132], GWAS of ADHD have identified genes which account for individual components of the condition, which may imply a genetic predisposition followed by further reinforcement by environmental factors and/or changes in the epigenome. As with other neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia, there is evidence of abnormalities in executive functioning in ADHD that are typically associated with prefrontal cortex dysfunction [133]. Several studies have identified alterations in DNA methylation in individuals with ADHD. Using DNA from cord blood together with behavioural profiles performed at 6 years of age, van Mil et al. reported a correlation between DNA methylation at candidate genes (primarily involved in dopamine and serotonin signalling) and an increased incidence of ADHD [134]. A similar study using a subset of the ALSPAC cohort for which epigenomic data from cord blood was available also showed altered DNA methylation at several genes associated with neurodevelopment in association with an increased risk of ADHD, but further added that these changes had disappeared in DNA from peripheral blood samples collected at the age of 7 years [135]. However, neither study accounted for gestational age at birth, although van Mil et al. did account for neonates born small for gestational age. In a sub-population of Chinese Han children, when PTB and other confounding factors were accounted for, DNA methylation of genes associated with dopamine signalling and histone modifications were associated with ADHD [136]. In this study the methylation state of p300, MYST4 (both histone acetyltransferases) and HDAC1 successfully predicted the development of ADHD with a relatively high degree of confidence.

6.3. ASD

Whilst there are studies on epigenetic alterations in brain tissue amongst ASD patients, the small sample size, age variation and heterogeneity of ASD are limitations of these studies and, importantly, causation is difficult to establish [137]. Both Ladd-Acosta et al. [138] and Nardone et al. [139] show many differentially methylated CpGs in the prefrontal cortex, cingulate gyrus, temporal cortex and cerebellum in post-mortem tissue from individuals with ASD. Key inflammatory mediators, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF) have been shown to be differentially methylated and expressed in post-mortem prefrontal cortex from individuals with ASD [139]. Using peripheral blood samples from monozygotic twins with and without ASD, differential methylation across several genes was observed [140].

There is increasing evidence for a role for histone acetylation in the pathogenesis of ASD. A recent study of H3K27ac showed widespread changes in post-mortem tissue in the prefrontal cortex, temporal cortex and cerebellum from ASD patients, including at genes involved in synaptic functionality and ion channels which have previously been implicated in ASD [141]. In a large cohort of Danish children, prenatal exposure to the HDAC inhibitor sodium valproate was associated with an increased incidence of ASD [142]. Finally, mutations in the histone acetyltransferase CREBBP (CREBP binding protein) have been shown to produce ASD like behaviours in a mouse model [143].

6.4. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)

FASD, caused by prenatal exposure to excess alcohol, is a leading cause of intellectual disability [144]. Excess alcohol intake is also a risk factor for PTB, as reviewed by Bailey and Sokol [145]. Many of the major pathologies associated with FASD are thought to involve epigenetic mechanisms. For example, acetaldehyde, an alcohol metabolite, is an inhibitor of DNMT1 [146] and FASD is also associated with altered availability of substrates for DNA methylation such as SAM [147] and with decreased folate uptake [148]. Since the pathogenesis of FASD is inevitably confounded by alcohol exposure, we have limited this review to discussing conditions which are a direct consequence of PTB.

7. IS THERE EVIDENCE FOR ALTERATIONS IN THE EPIGENOME IN PTB?

While much of the research on epigenetic causes of neurodevelopmental disorders has focused on specific disorders such as Rett syndrome, the environment associated with PTB has the potential to alter epigenetic control at multiple levels. A small longitudinal study examining DNA methylation in blood spots obtained from extremely preterm infants (less than 31 weeks of gestation) at birth and at 18 years’ old identified several differences in DNA methylation between individuals born at term or preterm at birth [149]. Interestingly this study noted that the differentially methylated regions identified at birth seemed to be controlled by specific transcription factors, perhaps indicating deregulation of transcription factors as a consequence of PTB. In addition, several studies using DNA from umbilical cord blood have shown altered DNA methylation in PTB [150-152]. These changes may, however, not be permanent; we and others have shown no persistent differences in DNA methylation at candidate genes at one year of age [153] and genome-wide at 18 years [149].

DNA methylation is dynamic during development, so that studies comparing the methylome at different gestational ages could show differences irrespective of any insults associated with PTB. To address this, a recent study used DNA from buccal cells from PTB neonates collected at term equivalent age, chosen to reflect the allostatic load of preterm birth and neonatal intensive care, in comparison to term born control neonates (n=36/group). DNA methylation was altered in several genes known to be central for neural development [154]. One of the genes identified as being differentially methylated in PTB, SLC7A5, is a transporter of branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) at the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [154], mutations of which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ASD [155]. In a mouse model, knockout of SLC7A5 is associated with a behavioural phenotype, which can be partially rescued by intraventricular injection of BCAAs [155]. Genes implicated in other diseases such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (SLC1A2 and APOL1) and altered social processing (NPBWR1) [154] were also found to be differentially methylated.

In addition to physiological stresses associated with PTB described above, psychological factors may also alter DNA methylation. For example, maternal separation is viewed as a severe early life stressor and increased methylation of the 1-F promoter region of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) has been demonstrated in preterm infants following at least 4 days’ maternal separation [156], which is typical following extreme PTB. Extreme maternal stress has also been associated with increased methylation at NR3C1 [157], with a dose dependent increase in DNA methylation with increasing perceived stress, although gestational age at birth was not accounted for in this study. When examining DNA obtained from a buccal swab of 15 year old adolescents, an increase in global DNA methylation was seen in those who were deemed to have had a more difficult childhood as ascertained through parental questionnaires, although again gestational age at birth was not controlled for [158].

Considering the relationship between the epigenome and environmental stimuli throughout life, the central issue with examination of post-mortem tissue is the inability to establish cause/consequence. The same caveats hold for the use of peripheral tissue samples which can be collected through a patient’s life such as blood, and in addition these samples may have limited predictive value for changes within the brain, given the tissue specificity of epigenetic marks. Recently it has become clear that use of buccal swabs for epigenetic studies is preferable to that of blood [159, 160] and a study using circulating blood and saliva samples from an African American population showed that methylation from salivary samples is more comparable to publicly available data sets of methylation in various brain regions [161]. Research into basic mechanisms that might delineate cause and consequence and in the tissue of interest has been somewhat slow in progression, partly due to the lack of a reliable and translatable animal model of PTB. Research in non-human primates is heavily constrained with ethical and legal issues and the translatability of commonly used rodent models can be unclear.

8. PTB ASSOCIATED FACTORS AS POTENTIAL EPIGENETIC REGULATORS?

8.1. Hypoxia

Hypoxia may modify the epigenome through several mechanisms. The TET enzymes and other α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases are particularly susceptible to environmental stimuli. The induction of the hypoxia response machinery through HIF1α, which is central to the cellular response to hypoxia [162] can have long lasting and wide-ranging effects which are known to include epigenetic alterations. Under normoxic conditions, the PHD proteins (part of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase family) are activated, then cleave and inactivate HIF-1α [162]. Under hypoxic conditions this process is attenuated and HIF-1α forms a heterodimer with HIF-1β, which can then bind DNA and induce hypoxia response genes [162]. Hypoxia can lead to long-term aberrant DNA methylation and shortened dendritic processes in mouse hippocampal cultures, which normalize upon return of normoxia [163]. Pre-treatment with 5-Azacytidine (a cytosine analogue that replaces methylated cytosine, thereby depleting 5mC levels) before induction of hypoxia potentiates brain injury in mice, an effect which can be attenuated with HIF-1α inhibition [164]. Hypoxia is associated with significant 5hmC enrichment at genomic HIF-1α binding sites and the TET enzymes are necessary for this induction [102]. A TET2-mediated increase in global 5hmC was seen in adult mice upon occlusion of the middle cerebral artery as a model of HI induction [165], although this finding is yet to be replicated in neonatal animals. During neonatal brain injury there is a coordinated inflammatory response, which can last weeks after the initial insult, leading to increased levels of TNFα [166]. TNFα upregulates NFκB which binds the promoter of HIF-1α and increases its transcription under normoxic conditions [167]. This provides a plausible link between inflammation and activation of the hypoxia response system, which could be important in the context of PTB where fluctuating oxygen levels can co-occur with inflammation (Fig. 1).

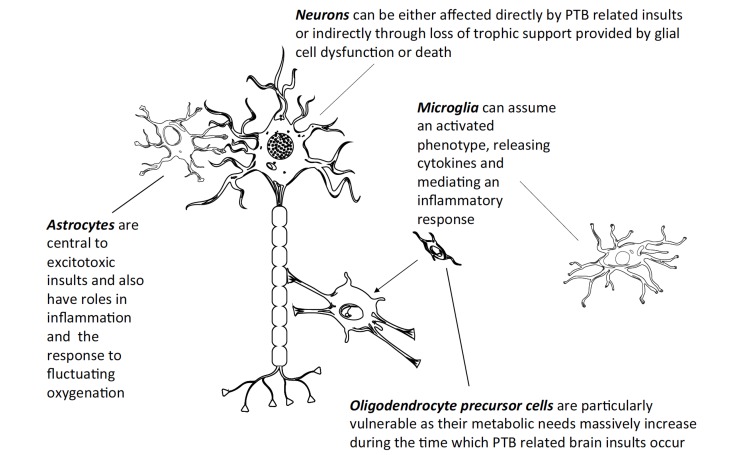

Fig. (1).

During PTB related insults, glia within the CNS are particularly vulnerable to stressors and mediate many of the pathogenic outcomes associated with PTB. Astrocytes are central to the excitotoxic response, which involves glutamate recycling and its de novo synthesis. Oligodendrocytes and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPC) are vulnerable to oxidative stress and other factors associated with hypoxia, inflammation and excitotoxicity as periods critical for their correct maturation and development overlap with the time during which PTB related insults may occur [48, 168] (surface area of an individual OPC’s membrane can increase up to 6,500 fold during these times [169]). The death of OPCs is of particular importance during development as this leads to a shortage of mature oligodendrocytes which may result in aberrant myelination in deep white matter tracts of the brain, leading to impaired signalling and neuronal death, which can be seen pathologically as periventricular leukomalacia, an anatomical feature of cerebral palsy. Microglia can become activated in response to infection in utero or postnatally, this population transition is central to the inflammatory response within the CNS and increased levels of microglial activation can also be seen in post-mortem ASD tissue in the prefrontal cortex of male patients [41].

8.2. TCA Cycle Dysregulation

In addition to the requirement of α-ketoglutarate for activity of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases, other components of the TCA cycle can impact on their activity: for example both succinate and fumarate can act as inhibitors of TET function [170]. The reactions of the TCA cycle are summarised in Fig. (2). Hypoxia may disrupt TCA cycle metabolism, for example during hypoxia α-ketoglutarate can be metabolized by lactate dehydrogenase and to a lesser extent by malate dehydrogenase to L-hydroxyglutarate [171], which can inhibit the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases. Further, several TCA cycle reactions may undergo shifts in their direction of action resulting in increased succinate production [172]. Indeed, succinate increases during hypoxia outside the nervous system [173], although it is unclear whether this also occurs in the brain, since several studies have found no evidence for succinate accumulation in astrocytes dissociated and cultured from 3 week old mice [174]. This may be due to the sequestration of α-ketoglutarate into glutamate production due to the massive extracellular release of glutamate which occurs during hypoxia-ischemia, resulting in the depletion of intracellular glutamate [175]. In mice, pre-treatment with α-ketoglutarate or oxaloacetate is protective against subsequent administration of the excitotoxic agent Kainic acid [176]. Further, administration of succinyl-phosphonate, which inhibits OGDH (oxoglutarate dehydrogenase) leading to increased cellular α-ketoglutarate, protects cultured cerebellar neurons against glutamate induced excitotoxicity [177]. This link between the glutamatergic system and the TCA cycle will be discussed in the next section.

Fig. (2).

During normoxia the TCA cycle has many reversible reactions with 2 “stop/go” points of irreversible reactions, at the conversion of oxaloacetate to citrate and likewise the conversion of α-ketoglutarate to succinyl CoA. During hypoxia, as the cell needs ATP and NAD+, the TCA metabolite flow predominately proceeds towards succinate production from α-ketoglutarate to account for ATP lost from electron transport failure and oxaloacetate is preferentially converted to malate to increase mitochondrial NAD. This leads to a build-up of fumarate and succinate which are known to inhibit the function of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases. It has also been shown that under hypoxic conditions α-ketoglutarate can be converted, primarily by lactate dehydrogenase, to L-hydroxyglutarate, which also can inhibit members of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase family. The metabolites which have been shown to either directly promote (α-ketoglutarate) or inhibit (succinate, fumarate and L-hydroxyglutarate) activity of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases are highlighted in bold.

8.3. Excitoxicity

Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase 1 (OGDH1) is a subunit of the OGDH enzyme complex which catalyses the conversion of α-ketoglutarate to succinyl-CoA as part of the TCA cycle and is alternatively spliced, so that a Ca2+ sensitive motif is present in OGDH within astrocytes but not neurons [178]. Inhibition of the OGDH complex has been shown to protect against excitotoxic mediated cell death in cerebellar granule cells [177]. The pathogenesis of the excitotoxic insult after hypoxia-ischaemia is partly mediated by the AMPA GluR2 receptor, expression of which has been directly associated with degree of hypoxic ischemic damage in both rats [179] and human post-mortem tissue [180]. Total glutamate has been shown to increase 150% in the 6 hours after a hypoxic ischemic insult in rats [80], indicating a massive need for de novo glutamate synthesis immediately after hypoxia-ischemia. The first step in this process is the formation of oxaloacetate from pyruvate, as mediated by pyruvate carboxylase, from where α-ketoglutarate can be formed and transaminated to glutamate [181]. However pyruvate carboxylase is not present in great quantities in mice until postnatal day (P)10 [182] (roughly equivalent to a term human infant [183]), so that the massive glutamate increase may not be occurring through de novo synthesis. Instead, glutamate may be preferentially recycled to reform more glutamate rather than entering the TCA cycle and α-ketoglutarate already in the TCA cycle may be diverted to glutamate formation at the expense of the TCA cycle and the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases.

During severe ischemia, the main mechanism increasing glutamate within the synapse is reversed uptake of astrocytic transporters due to altered ionic gradients [184]. This is important as it outlines an excitotoxic cycle whereby ATP cannot be produced in sufficient quantities due to hypoxia and therefore glutamate uptake, which is an energy intensive process, cannot occur. This leads to further receptor activation and an increased flux of Na+ out of the cell, further driving ionic gradients towards reverse uptake of glutamate and depletion of intracellular glutamate stores, which could lead to altered availability of α-ketoglutarate. This could be important, since the TET enzymes are particularly susceptible to α-ketoglutarate fluctuations due to a relatively low Km (the concentration of α-ketoglutarate which is necessary to produce half of the maximum velocity of TET meditated hydroxymethylation) [170], although a key question is whether alterations in sub-cellular localizations of α-ketoglutarate during PTB related excitotoxicity and/or α-ketoglutarate sequestration to glutamate production can alter α-ketoglutarate levels sufficiently in the nucleus to affect activity of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases.

8.4. Inflammation

It has been postulated that the epigenetic alterations that occur in association with ASD may have inflammatory origins, as reviewed by Nardone and Elliot [185]. Maternal immune activation has been linked with ASD-like behaviour in offspring of animal models [186]. IL6 has specifically been implicated, with increased maternal levels producing an ASD like phenotype [186]. IL6 has also been shown to promote DNMT1 activity through increased nuclear translocation [187]. The inflammatory stimulant Poly I:C, when given to female mice at embryonic day (E)9, produces global hypoacetylation of H3K9, H3K14 and H4K8 in cortical regions at P24, and associated behavioural abnormalities [188]. Using a similar paradigm it has also been shown that maternal inflammation can produce hypomethylation of key epigenetic factors, MECP2 and LINE1 in the hypothalamus [189]. The TET proteins have also been shown to have roles in inflammatory regulation. TET2 can control IL1β production from macrophages via NLRP3 [190] and TET3 has been shown to inhibit IFN type I [191].

9. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

There are many caveats that must be considered when performing studies to determine the potential role of epigenetic dysregulation in mediating the adverse consequences of PTB. Many studies that implicate altered DNA methylation in neurodevelopmental disorders use techniques to analyse DNA methylation that do not differentiate between 5mC and 5hmC, which have different functions and dynamics [192]. Additionally, the tissue specificity of DNA methylation patterns means that DNA methylation in one tissue may not be a good proxy for methylation elsewhere, potentially limiting the biological meaning of the findings. It is however becoming clear that methylation from buccal swabs is a reasonably informative substitute for methylation within the brain [161]. A further complication is that differences in cell-subtype populations are a major confounder in many studies i.e. differences in DNA methylation may simply reflect changes in cell/tissue composition. Further, much inter-individual variation in DNA methylation is attributable to DNA sequence polymorphisms, which modulate risk of white matter disease in preterm infants [193, 194], and transcriptomic variability means that DNA methylation changes may be the consequence rather than the cause of inter-individual differences in transcription. Finally, it is important to remember that the disease itself may lead to changes in DNA methylation rather than vice versa [195].

We suggest that epigenetic dysregulation could be one mechanism accounting for the associations between preterm birth and conditions such as ASD, cerebral palsy, and both syndromic and non-syndromic intellectual disabilities. Although the potential contributions of epigenetic dysregulation in mediating the neurodevelopmental consequences of PTB are poorly understood, many factors that are associated with the pathogenesis of PTB-induced brain injury may also affect the epigenome. Understanding these mechanisms could lead to the development of strategies for the early identification of children at risk and/or novel therapeutics and management strategies aimed at limiting the adverse neurodevelopmental consequences of preterm birth.

CONCLUSION

The rate of PTB has not declined over the past 20 years [196] and as discussed earlier, there is a marked increase of neurodevelopmental disorders amongst those born preterm. Considering the substantial socio-economic burden that comes with this, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms underlying this association. Understanding these, as well as a more thorough knowledge of any epigenetic dysregulation associated with PTB, including any potential dysfunction of the α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase family, which may be particularly vulnerable to environmental alterations, is necessary to fully understand and to more comprehensively treat PTB related brain injury and to improve neurodevelopmental outcome.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

EF is funded by a PhD studentship from Medical Research Scotland (PhD-878-2015), in collaboration with Aquila BioMedical, Edinburgh, UK.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the writing of the article and approved the final draft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ananth C.V., Vintzileos A.M. Epidemiology of preterm birth and its clinical subtypes. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19(12):773–782. doi: 10.1080/14767050600965882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blencowe H., Cousens S., Chou D., Oestergaard M., Say L., Moller A-B., Kinney M., Lawn J. Born too soon preterm birth action group. Born too soon: The global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod. Health. 2013;10(Suppl. 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2. https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/ articles/10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slattery M.M., Morrison J.J. Preterm delivery. Lancet. 2002;360(9344):1489–1497. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11476-0. http://www.thelancet.com/ series/preterm-birth [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office for National Statistics Pregnancy and ethnic factors influencing births and infant mortality. 2013 https:// www.ons.gov.uk/ releases/pregnancyandethnicfactorsinfluencingbirthsandinfantmorta

- 5.Callaghan W.M., MacDorman M.F., Shapiro-Mendoza C.K., Barfield W.D. Explaining the recent decrease in US infant mortality rate, 2007-2013. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;216(1):73.e1–73.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.097. http://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378 (16)30818-3/fulltext [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson-Costello D., Friedman H., Minich N., Siner B., Taylor G., Schluchter M., Hack M. Improved neurodevelopmental outcomes for extremely low birth weight infants in 2000-2002. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):37–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson-Costello D., Friedman H., Minich N., Fanaroff A.A., Hack M. Improved survival rates with increased neurodevelopmental disability for extremely low birth weight infants in the 1990s. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):997–1003. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore T., Hennessy E.M., Myles J., Johnson S.J., Draper E.S., Costeloe K.L., Marlow N. Neurological and developmental outcome in extremely preterm children born in England in 1995 and 2006: The EPICure studies. BMJ. 2012;345:e7961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7961. https://www.bmj.com/content/345/bmj.e7961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen K.A., Brandon D.H. Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: Pathophysiology and experimental treatments. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2011;11(3):125–133. doi: 10.1053/j.nainr.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trønnes H., Wilcox A.J., Lie R.T., Markestad T., Moster D. Risk of cerebral palsy in relation to pregnancy disorders and preterm birth: A national cohort study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014;56(8):779–785. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolevzon A., Gross R., Reichenberg A. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007;161(4):326–333. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalman C., Allebeck P., Cullberg J., Grunewald C., Köster M. Obstetric complications and the risk of schizophrenia: A longitudinal study of a national birth cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):234–240. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhutta A.T., Cleves M.A., Casey P.H., Cradock M.M., Anand K.J.S. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288(6):728–737. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bax M., Goldstein M., Rosenbaum P., Leviton A., Paneth N., Dan B., Jacobsson B., Damiano D., Executive Committee for the Definition of Cerebral Palsy Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005;47(8):571–576. doi: 10.1017/s001216220500112x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Back S.A., Miller S.P. Brain injury in premature neonates: A primary cerebral dysmaturation disorder? Ann. Neurol. 2014;75(4):469–486. doi: 10.1002/ana.24132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volpe J.J. Neurobiology of periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant. Pediatr. Res. 2001;50(5):553–562. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeargin-Allsopp M., Van Naarden Braun K., Doernberg N.S., Benedict R.E., Kirby R.S., Durkin M.S. Prevalence of cerebral palsy in 8-year-old children in three areas of the United States in 2002: A multisite collaboration. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):547–554. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marlow N., Wolke D., Bracewell M.A., Samara M. Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352(1):9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Short E.J., Klein N.K., Lewis B.A., Fulton S., Eisengart S., Kercsmar C., Baley J., Singer L.T. Cognitive and academic consequences of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and very low birth weight: 8-year-old outcomes. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):e359. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.e359. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/ 112/5 /e359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller S.L., Huppi P.S., Mallard C. The consequences of fetal growth restriction on brain structure and neurodevelopmental outcome. J. Physiol. 2016;594(4):807–823. doi: 10.1113/JP271402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah D.K., Doyle L.W., Anderson P.J., Bear M., Daley A.J., Hunt R.W., Inder T.E. Adverse neurodevelopment in preterm infants with postnatal sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis is mediated by white matter abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging at term. J. Pediatr. 2008;153(2):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anblagan D., Pataky R., Evans M.J., Telford E.J., Serag A., Sparrow S., Piyasena C., Semple S.I., Wilkinson A.G., Bastin M.E., Boardman J.P. Association between preterm brain injury and exposure to chorioamnionitis during fetal life. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep37932. https://www.nature.com/articles/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Wu Y.W., Escobar G.J., Grether J.K., Croen L.A., Greene J.D., Newman T.B. Chorioamnionitis and cerebral palsy in term and near-term infants. JAMA. 2003;290(20):2730–2732. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.20.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polanczyk G., de Lima M.S., Horta B.L., Biederman J., Rohde L.A. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–948. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weyandt L., Swentosky A., Gudmundsdottir B.G. Neuroimaging and ADHD: fMRI, PET, DTI findings, and methodological limitations. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2013;38(4):211–225. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2013.783833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mill J., Petronis A. Pre- and Peri-natal environmental risks for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): The potential role of epigenetic processes in mediating susceptibility. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2008;49(10):1020–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray E., Pearson R., Fernandes M., Santos I.S., Barros F.C., Victora C.G., Stein A., Matijasevich A. Are fetal growth impairment and preterm birth causally related to child attention problems and ADHD? Evidence from a comparison between high-income and middle-income cohorts. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2016;70(7):704–709. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindstrom K., Lindblad F., Hjern A. Preterm birth and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in schoolchildren. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):858–865. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perricone G., Morales M.R., Anzalone G. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of moderately preterm birth: Precursors of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder at preschool age. Springerplus. 2013;2(1):221. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-221. https://springerplus.springeropen.com/ articles/10.1186/2193-1801-2-221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu S-M., Tsai M-H., Hwang F-M., Hsu J-F., Huang H.R., Huang Y-S. The relationship between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and premature infants in Taiwanese: A case control study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-85. https:// bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-244X-12-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson S., Marlow N. Early and long-term outcome of infants born extremely preterm. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017;102(1):97–102. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baird G., Simonoff E., Pickles A., Chandler S., Loucas T., Meldrum D., Charman T. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: The special needs and autism project (SNAP). Lancet. 2006;368(9531):210–215. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Werling D.M., Geschwind D.H. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2013;26(2):146–153. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32835ee548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor B., Jick H., Maclaughlin D. Prevalence and incidence rates of autism in the UK: Time trend from 2004-2010 in children aged 8 years. BMJ Open. 2013;3(10):e003219. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003219. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/10/e003219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miles J.H. Autism spectrum disorders-A genetics review. Genet. Med. 2011;13(4):278–294. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ff67ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sáez M.A., Fernández-Rodríguez J., Moutinho C., Sanchez-Mut J.V., Gomez A., Vidal E., Petazzi P., Szczesna K., Lopez-Serra P., Lucariello M., Lorden P., Delgado-Morales R., de la Caridad O.J., Huertas D., Gelpí J.L., Orozco M., López-Doriga A., Milà M., Perez-Jurado L.A., Pineda M., Armstrong J., Lázaro C., Esteller M. Mutations in JMJD1C are involved in rett syndrome and intellectual disability. Genet. Med. 2016;18(4):378–385. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hultman C.M., Sparén P., Cnattingius S. Perinatal risk factors for infantile autism. Epidemiology. 2002;13(4):417–423. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zerbo O., Iosif A-M., Walker C., Ozonoff S., Hansen R.L., Hertz-Picciotto I. Is maternal influenza or fever during pregnancy associated with autism or developmental delays? Results from the CHARGE (CHildhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment) study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013;43(1):25–33. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1540-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abdallah M.W., Larsen N., Grove J., Nørgaard-Pedersen B., Thorsen P., Mortensen E.L., Hougaard D.M. Amniotic fluid inflammatory cytokines: Potential markers of immunologic dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;14(7):528–538. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.639803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takano T. Role of microglia in autism: Recent advances. Dev. Neurosci. 2015;37(3):195–202. doi: 10.1159/000398791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Auyeung B., Lombardo M.V., Baron-Cohen S. Prenatal and postnatal hormone effects on the human brain and cognition. Pflugers Arch. 2013;465(5):557–571. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Messias E.L., Chen C-Y., Eaton W.W. Epidemiology of schizophrenia: Review of findings and myths. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2007;30(3):323–338. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown A.S., Vinogradov S., Kremen W.S., Poole J.H., Deicken R.F., Penner J.D., McKeague I.W., Kochetkova A., Kern D., Schaefer C.A. Prenatal exposure to maternal infection and executive dysfunction in adult schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009;166(6):683–690. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buka S.L., Tsuang M.T., Torrey E.F., Klebanoff M.A., Wagner R.L., Yolken R.H. Maternal cytokine levels during pregnancy and adult psychosis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2001;15(4):411–420. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Urakubo A., Jarskog L.F., Lieberman J.A., Gilmore J.H. Prenatal exposure to maternal infection alters cytokine expression in the placenta, amniotic fluid, and fetal brain. Schizophr. Res. 2001;47(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goudriaan A., de Leeuw C., Ripke S., Hultman C.M., Sklar P., Sullivan P.F., Smit A.B., Posthuma D., Verheijen M.H.G. Specific glial functions contribute to schizophrenia susceptibility. Schizophr. Bull. 2014;40(4):925–935. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Back S.A., Luo N.L., Borenstein N.S., Levine J.M., Volpe J.J., Kinney H.C. Late oligodendrocyte progenitors coincide with the developmental window of vulnerability for human perinatal white matter injury. J. Neurosci. 2001;21(4):1302–1312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01302.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaindl A.M., Favrais G., Gressens P. Molecular mechanisms involved in injury to the preterm brain. J. Child Neurol. 2009;24(9):1112–1118. doi: 10.1177/0883073809337920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt-Kastner R., van Os J., Esquivel G., Steinbusch H.W.M., Rutten B.P.F. An environmental analysis of genes associated with schizophrenia: Hypoxia and vascular factors as interacting elements in the neurodevelopmental model. Mol. Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1194–1205. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liggins G.C. Premature delivery of foetal lambs infused with glucocorticoids. J. Endocrinol. 1969;45(4):515–523. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0450515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonanno C., Wapner R.J. Antenatal corticosteroids in the management of preterm birth: Are we back where we started? Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2012;39(1):47–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu G., Segrè J., Gülmezoglu A., Mathai M., Smith J.M., Hermida J., Simen-Kapeu A., Barker P., Jere M., Moses E., Moxon S.G., Dickson K.E., Lawn J.E., Althabe F. Working Group for UN Commission of Life Saving Commodities Antenatal Corticosteroids. Antenatal corticosteroids for management of preterm birth: A multi-country analysis of health system bottlenecks and potential solutions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(Suppl. 2):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-15-S2-S3. https:// bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/ articles/10.1186/1471-2393-15-S2-S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siebe H., Baude G., Lichtenstein I., Wang D., Bühler H., Hoyer G.A., Hierholzer K. Metabolism of dexamethasone: Sites and activity in mammalian tissues. Ren. Physiol. Biochem. 1993;16(1-2):79–88. doi: 10.1159/000173753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez-Rodriguez P.J., Xiong F., Li Y., Zhou J., Zhang L. Fetal hypoxia increases vulnerability of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats: Role of glucocorticoid receptors. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014;65:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tijsseling D., Wijnberger L.D.E., Derks J.B., van Velthoven C.T.J., de Vries W.B., van Bel F., Nikkels P.G.J., Visser G.H.A., Roberts D., Dalziel S., Meijer O., de Kloet E., Liggins G., Huang W., Beazley L., Quinlivan J., Evans S., Newnham J., Jobe A., Wada N., Berry L., Ikegami M., Ervin M., Kanagawa T., Tomimatsu T., Hayashi S., Shioji M., Fukuda H., French N., Hagan R., Evans S., Godfrey M., Newnham J., Abbasi S., Hirsch D., Davis J., Tolosa J., Stouffer N., Dirnberger D., Yoder B., Gordon M., Murphy K., Hannah M., Willan A., Hewson S., Ohlsson A., Crowther C., Haslam R., Hiller J., Doyle L., Robinson J., Wapner R., Sorokin Y., Thom E., Johnson F., Dudley D., Guinn D., Atkinson M., Sullivan L., Lee M., MacGregor S., Kloet E.D., Rosenfeld P., Eekelen J.V., Sutanto W., Levine S., Olton D., Walker J., Gage F., Eichenbaum H., Otto T., Cohen N., Epstein M., Farrell P., Sparks J., Pepe G., Driscoll S., Uno H., Lohmiller L., Thieme C., Kemnitz J., Engle M., Noorlander C., Noorlander C., Graan P.D., Visser G., Noorlander C., Visser G., Ramakers G., Nikkels P., Graan P.D., Visser G., Eilers P., Elferink-Stinkens P., Merkus H., Wit J., Korteweg F., Gordijn S., Timmer A., Erwich J., Bergman K., Bouman K., Ravise J., Heringa M., Holm J., Groenendaal F., Lammers H., Smit D., Nikkels P., Scholzen T., Gerdes J., Sumi S. 3rd, W.T.; Kessler, D.; Scheepens, A.; Van de Waarenburg, M.; Van den Hove, D.; Blanco, C.; Adamo, M.; Werner, H.; Farnsworth, W.; Raizada, M.; Schaaf, M.; Hoetelmans, R.; de Kloet, E.; Vreugdenhil, E.; Molteni, R.; Fumagalli, F.; Magnaghi, V.; Roceri, M.; Gennarelli, M.; Wagner, J.; Black, I.; DiCicco-Bloom, E.; Aberg, M.; Aberg, N.; Hedbacker, H.; Oscarsson, J.; Eriksson, P.; Murphy, D.; MacArthur, B.; Howie, R.; Dezoete, J.; Elkins, J.; Schmand, B.; Neuvel, J.; Haas, H.S.; Hoeks, J.; Treffers, P.; Dessens, A.; Haas, H.; Koppe, J.; Dalziel, S.; Rea, H.; Walker, N.; Parag, V.; Mantell, C.; Dalziel, S.; Lim, V.; Lambert, A.; McCarthy, D.; Parag, V.; French, N.; Hagan, R.; Evans, S.; Mullan, A.; Newnham, J.; Barrington, K. Effects of antenatal glucocorticoid therapy on hippocampal histology of preterm infants. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033369. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/ article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0033369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alexander N., Rosenlöcher F., Dettenborn L., Stalder T., Linke J., Distler W., Morgner J., Miller R., Kliegel M., Kirschbaum C. Impact of antenatal glucocorticoid therapy and risk of preterm delivery on intelligence in term-born children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;101(2):581–589. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horner H.C., Packan D.R., Sapolsky R.M. Glucocorticoids inhibit glucose transport in cultured hippocampal neurons and glia. Neuroendocrinology. 1990;52(1):57–64. doi: 10.1159/000125539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.LeBlanc M.H., Huang M., Vig V., Patel D., Smith E.E. Glucose affects the severity of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in newborn pigs. Stroke. 1993;24(7):1055–1062. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.7.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Antonow-Schlorke I., Helgert A., Gey C., Coksaygan T., Schubert H., Nathanielsz P.W., Witte O.W., Schwab M. Adverse effects of antenatal glucocorticoids on cerebral myelination in sheep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;113(1):142–151. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181924d3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGowan J.E., Sysyn G., Petersson K.H., Sadowska G.B., Mishra O.P., Delivoria-Papadopoulos M., Stonestreet B.S. Effect of dexamethasone treatment on maturational changes in the NMDA receptor in sheep brain. J. Neurosci. 2000;20(19):7424–7429. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07424.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levitt N.S., Lindsay R.S., Holmes M.C., Seckl J.R. Dexamethasone in the last week of pregnancy attenuates hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor gene expression and elevates blood pressure in the adult offspring in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;64(6):412–418. doi: 10.1159/000127146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Vries A., Holmes M.C., Heijnis A., Seier J.V., Heerden J., Louw J., Wolfe-Coote S., Meaney M.J., Levitt N.S., Seckl J.R. Prenatal dexamethasone exposure induces changes in nonhuman primate offspring cardiometabolic and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117(4):1058–1067. doi: 10.1172/JCI30982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Noguchi K.K., Walls K.C., Wozniak D.F., Olney J.W., Roth K.A., Farber N.B. Acute neonatal glucocorticoid exposure produces selective and rapid cerebellar neural progenitor cell apoptotic death. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(10):1582–1592. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tam E.W.Y., Chau V., Ferriero D.M., Barkovich A.J., Poskitt K.J., Studholme C., Fok E.D-Y., Grunau R.E., Glidden D.V., Miller S.P. Preterm cerebellar growth impairment after postnatal exposure to glucocorticoids. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3(105):105ra105. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002884. http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/ 3/105/105ra105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Committee on Fetus and Newborn Postnatal corticosteroids to treat or prevent chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2002;109(2):330–338. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barrington K.J. The adverse neuro-developmental effects of postnatal steroids in the preterm infant: A systematic review of RCTs. BMC Pediatr. 2001;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-1-1. https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral. com/articles/10.1186/1471-2431-1-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Doyle L.W., Davis P.G., Morley C.J., McPhee A., Carlin J.B., DART Study Investigators Outcome at 2 years of age of infants from the DART study: A multicenter, international, randomized, controlled trial of low-dose dexamethasonef. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):716–721. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Doyle L.W., Davis P.G., Morley C.J., McPhee A., Carlin J.B., DART Study Investigators Low-dose dexamethasone facilitates extubation among chronically ventilator-dependent infants: A multicenter, international, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):75–83. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ko M-C., Hung Y-H., Ho P-Y., Yang Y-L., Lu K-T. Neonatal glucocorticoid treatment increased depression-like behaviour in adult rats. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(12):1995–2004. doi: 10.1017/S1461145714000868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Flagel S.B., Vázquez D.M., Watson S.J., Neal C.R. Effects of tapering neonatal dexamethasone on rat growth, neurodevelopment, and stress response. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002;282(1):R55–R63. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2002.282.1.R55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Halladay A.K., Bishop S., Constantino J.N., Daniels A.M., Koenig K., Palmer K., Messinger D., Pelphrey K., Sanders S.J., Singer A.T., Taylor J.L., Szatmari P. Sex and gender differences in autism spectrum disorder: summarizing evidence gaps and identifying emerging areas of priority. Mol. Autism. 2015;6:36. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0019-y. https://molecularautism.biomedcentral.com/articles/ 10.1186/s13229-015-0019-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kapellou O., Counsell S.J., Kennea N., Dyet L., Saeed N., Stark J., Maalouf E., Duggan P., Ajayi-Obe M., Hajnal J., Allsop J.M., Boardman J., Rutherford M.A., Cowan F., Edwards A.D. Abnormal cortical development after premature birth shown by altered allometric scaling of brain growth. PLoS Med. 2006;3(8):e265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030265. http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/ article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0030265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Santos-Galindo M., Acaz-Fonseca E., Bellini M.J., Garcia-Segura L.M., Magistretti P., Attwell D., Buchan A., Charpak S., Lauritzen M., Macvicar B., Newman E., Gundersen V., Volterra A., Araque A., Navarrete M., Cerciat M., Unkila M., Garcia-Segura L., Arevalo M., Bellini M., Hereñú C., Goya R., Garcia-Segura L., Dong Y., Benveniste E., Blanco A., Valles S., Pascual M., Guerri C., Krasowska-Zoladek A., Banaszewska M., Kraszpulski M., Konat G., Konat G., Krasowska-Zoladek A., Kraszpulski M., Liao C., Wang S., Chen Y., Wang H., Wu J., Gorina R., Font-Nieves M., Márquez-Kisinousky L., Santalucia T., Planas A., Amateau S., McCarthy M., Suárez I., Bodega G., Rubio M., Fernandez B., Garcia-Segura L., Dueñas M., Busiguina S., Naftolin F., Chowen J., Collado P., Beyer C., Hutchison J., Holman S., Mong J., McCarthy M., Kuo J., Hamid N., Bondar G., Dewing P., Clarkson J., Micevych P., Suárez I., Bodega G., Rubio M., Fernández B., Garcia-Segura L., Suarez I., Segovia S., Tranque P., Calés J., Aguilera P., Olmos G., Guillamón A., Rasia-Filho A., Xavier L., dos Santos P., Gehlen G., Achaval M., Johnson R., Breedlove S., Jordan C., Conejo N., González-Pardo H., Cimadevilla J., Argüelles J., Díaz F., Vallejo-Seco G., Arias J., Arias C., Zepeda A., Hernández-Ortega K., Leal-Galicia P., Lojero C., Camacho-Arroyo I., Garcia-Segura L., Chowen J., Párducz A., Naftolin F., Garcia-Segura L., Azad N., Al Bugami M., Loy-English I., Figueira M., Ouakinin S., Jobin C., Larochelle C., Parpal H., Coyle P., Duquette P., Melcangi R., Garcia-Segura L., Voskuhl R., Liu M., Hurn P., Roselli C., Alkayed N., Garcia-Segura L., Veiga S., Sierra A., Melcangi R., Azcoitia I., Saldanha C., Duncan K., Walters B., Garcia-Segura L., Melcangi R., Sinchak K., Mills R., Tao L., LaPolt P., Lu J., Micevych P., Veiga S., Garcia-Segura L., Azcoitia I., Ciriza I., Azcoitia I., Garcia-Segura L., De Nicola A., Labombarda F., Deniselle M., Gonzalez S., Garay L., Meyer M., Gargiulo G., Guennoun R., Schumacher M., Stein D., Wright D., Moralí G., Montes P., Hernández-Morales L., Monfil T., Espinosa-García C., Cervantes M., Dang J., Mitkari B., Kipp M., Beyer C., Itzhak Y., Roig-Cantisano A., Norenberg M., Sierra A., Lavaque E., Sierra A., Azcoitia I., Garcia-Segura L., Papadopoulos V., Baraldi M., Guilarte T., Knudsen T., Lacapère J., Lindemann P., Norenberg M., Nutt D., Weizman A., Zhang M., Gavish M., Arnold A., Gorski R., Pistritto G., Franzese O., Pozzoli G., Mancuso C., Tringali G., Preziosi P., Navarra P., Caruso D., D’Intino G., Giatti S., Maschi O., Pesaresi M., Calabrese D., Garcia-Segura L., Calza L., Melcangi R., Pesaresi M., Maschi O., Giatti S., Garcia-Segura L., Caruso D., Melcangi R., Rone M., Fan J., Papadopoulos V., Garcia-Estrada J., Del Rio J., Luquin S., Soriano E., Garcia-Segura L., García-Estrada J., Luquín S., Fernández A., Garcia-Segura L., Grossman K., Goss C., Stein D., Barreto G., Veiga S., Azcoitia I., Garcia-Segura L., Garcia-Ovejero D., Gehlert D., Stephenson D., Schober D., Rash K., Clemens J., Rojas S., Martín A., Arranz M., Pareto D., Purroy J., Verdaguer E., Llop J., Gómez V., Gispert J., Millán O., Chamorro A., Planas A., Chen M., Guilarte T., Veiga S., Azcoitia I., Garcia-Segura L., Veiga S., Carrero P., Pernia O., Azcoitia I., Garcia-Segura L., Veenman L., Papadopoulos V., Gavish M., Veenman L., Shandalov Y., Gavish M., Sierra A., Lavaque E., Perez-Martin M., Azcoitia I., Hales D., Garcia-Segura L., Lavaque E., Mayen A., Azcoitia I., Tena-Sempere M., Garcia-Segura L., Arnold A., Mong J., Glaser E., McCarthy M., Liu M., Oyarzabal E., Yang R., Murphy S., Hurn P., Farber J., Dufour J., Dziejman M., Liu M., Leung J., Lane T., Luster A., Rothwell N., Mason J., Suzuki K., Chaplin D., Matsushima G., Campbell I., Abraham C., Masliah E., Kemper P., Inglis J., Oldstone M., Mucke L., Swartz K., Liu F., Sewell D., Schochet T., Campbell I., Sandor M., Fabry Z., Penkowa M., Giralt M., Lago N., Camats J., Carrasco J., Hernandez J., Molinero A., Campbell I., Hidalgo J., Quintana A., Molinero A., Borup R., Nielsen F., Campbell I., Penkowa M., Hidalgo J., Syed M., Phulwani N., Kielian T., Worrall N., Chang K., LeJeune W., Misko T., Sullivan P., Ferguson T., Williamson J., Kim S., Steelman A., Koito H., Li J., Su Z., Yuan Y., Chen J., Zhu Y., Qiu Y., Zhu F., Huang A., He C. Sex differences in the inflammatory response of primary astrocytes to lipopolysaccharide. Biol. Sex Differ. 2011;2(1):7. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-2-7. https://bsd.biomedcentral.com/articles/ 10.1186/2042-6410-2-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Waddell J., Hanscom M., Edwards N.S., McKenna M.C., McCarthy M.M. Sex differences in cell genesis, hippocampal volume and behavioral outcomes in a rat model of neonatal HI. Exp. Neurol. 2016;275(2):285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mouton P.R., Long J.M., Lei D-L., Howard V., Jucker M., Calhoun M.E., Ingram D.K. Age and gender effects on microglia and astrocyte numbers in brains of mice. Brain Res. 2002;956(1):30–35. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03475-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hoffman J.F., Wright C.L., McCarthy M.M. A critical period in purkinje cell development is mediated by local estradiol synthesis, disrupted by inflammation, and has enduring consequences only for males. J. Neurosci. 2016;36(39):10039–10049. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1262-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Demarest T.G., Schuh R.A., Waite E.L., Waddell J., McKenna M.C., Fiskum G. Sex dependent alterations in mitochondrial electron transport chain proteins following neonatal rat cerebral hypoxic-ischemia. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2016;48(6):591–598. doi: 10.1007/s10863-016-9678-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Demarest T.G., Waite E.L., Kristian T., Puche A.C., Waddell J., McKenna M.C., Fiskum G. Sex-dependent mitophagy and neuronal death following rat neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Neuroscience. 2016;335:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morken T.S., Brekke E., Håberg A., Widerøe M., Brubakk A-M., Sonnewald U. Altered astrocyte-neuronal interactions after hypoxia-ischemia in the neonatal brain in female and male rats. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2777–2785. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mitchell A.M., Palettas M., Christian L.M. Fetal sex is associated with maternal stimulated cytokine production, but not serum cytokine levels, in human pregnancy. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017;60:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ohlsson A., Roberts R., Schmidt B., Davis P., Moddeman D., Saigal S., Solimano A., Vincer M., Wright L. The trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms (TIPP) Investigators. Male/female differences in indomethacin effects in preterm infants. J. Pediatr. 2005;147(6):860–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ment L.R., Vohr B.R., Makuch R.W., Westerveld M., Katz K.H., Schneider K.C., Duncan C.C., Ehrenkranz R., Oh W., Philip A.G.S., Scott D.T., Allan W.C. Prevention of intraventricular hemorrhage by indomethacin in male preterm infants. J. Pediatr. 2004;145(6):832–834. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saluz H.P., Jiricny J., Jost J.P. Genomic sequencing reveals a positive correlation between the kinetics of strand-specific DNA demethylation of the overlapping estradiol/glucocorticoid-receptor binding sites and the rate of avian vitellogenin mRNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83(19):7167–7171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.19.7167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yokomori N., Moore R., Negishi M. Sexually dimorphic DNA demethylation in the promoter of the Slp (Sex-limited protein) gene in mouse liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92(5):1302–1306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spiers H., Hannon E., Schalkwyk L.C., Smith R., Wong C.C.Y., O’Donovan M.C., Bray N.J., Mill J. Methylomic trajectories across human fetal brain development. Genome Res. 2015;25(3):338–352. doi: 10.1101/gr.180273.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Simpkin A.J., Suderman M., Gaunt T.R., Lyttleton O., McArdle W.L., Ring S.M., Tilling K., Davey Smith G., Relton C.L. Longitudinal analysis of DNA methylation associated with birth weight and gestational age. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24(13):3752–3763. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bird A. Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature. 2007;447(7143):396–398. doi: 10.1038/nature05913. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature05913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith Z.D., Meissner A. DNA methylation: Roles in mammalian development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14(3):204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]