Abstract

Sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) is a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD +)-dependent class III histone deacetylase. We have reported that HBx (hepatitis B virus X protein)-elevated SIRT2 promotes HBV replication and hepatocarcinogenesis. However, the potential anti-HBV effect of AGK2, a selective inhibitor of SIRT2, has not been reported. Here, the role of AGK2 on HBV replication was examined in the HepAD38 and HepG2-NTCP cell lines. The HBV genome was stably integrated in HepAD38 cell line which expresses HBV under the control of tetracycline. The HepG2-NTCP cells expressing the sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) receptor are susceptible to HBV infection. We found that AGK2 exhibited a robust anti-HBV activity with minimal hepatotoxicity. AGK2 inhibited the expression of HBV total and 3.5kb RNAs, DNA replicative intermediates and HBV core protein (HBc). Moreover, AGK2 treatment suppressed the secretion of the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Importantly, AGK2 treatment inhibited serum HBV DNA, HBeAg and HBsAg levels as well as hepatic HBV DNA, RNA and HBc in the HBV transgenic mice. The results indicated that AGK2, as a SIRT2 inhibitor, might be a new therapeutic option for controlling HBV infection.

Keywords: AGK2, HBV, SIRT2

1. Introduction

Human hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a hepatotropic DNA virus that causes acute and chronic hepatitis, leading to HBV-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma 1. Despite the use of effective preventive vaccines for more than three decades, chronic hepatitis B virus infection remains a serious health problem worldwide with 240 million people chronically infected 2, 3. HBV has a 3.2 Kbp partially double-stranded relaxed circular (rc) DNA genome 4. After entry into the cytoplasm of hepatic cells, rcDNA in the nucleocapsid is delivered into the nucleus where it convertes into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), which then serves as a template to transcribe pre-genomic RNA (pgRNA) and other subgenomic viral RNAs. So far there are two principal therapy strategies: interferon alpha and nucleotide analogue therapy 5, 6. But interferon alpha is expensive and can be used for only a limited duration 7, and, nucleotide analogue is susceptible to viral resistance when used for long-term treatment 8. More effective therapies are urgently needed for the treatment of HBV.

SIRT2, an NAD+-dependent class III histone deacetylase 9, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cancer 10, genomic instability 11 and bacterial infection 12. We previously reported that SIRT2 was upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma where it facilitated HCC cells proliferation and epithelial to mesenchymal transition 13. Moreover, we found that viral protein HBx could upregulate SIRT2 by targeting its promoter. Consequently, SIRT2 facilitated HBV transcription and replication and promoted HBV-mediated HCC 14. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that inhibiting SIRT2 may be a potential strategy for HBV therapy. AGK2 is a selective SIRT2 inhibitor, and previous studies have shown that administration of AGK2 could rescue the α-Synuclein-mediated toxicity of dorsomedial dopamine neurons 15. Treatment of AGK2 could lead to C6 glioma cells apoptosis through the caspase-3-dependent pathway 16. And inhibition of SIRT2 by AGK2 could decrease merlin-mutant mouse Schwann cells (MSC) viability without significant influence on the wild-type MSC 17. However, the effect of AGK2 on HBV infection is not well known.

In this study, we found that the AGK2 treatment decreased HBV RNAs, replicative intermediates, HBc, as well as the secretion of HBeAg and HBsAg. Importantly, we further confirmed the effect of AGK2 on HBV replication in vivo. These data suggested that AGK2 may be a new strategy for controlling HBV infection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Cell culture

The HepAD38 and HepG2-NTCP cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, New York, USA), and 400 μg/ml of G418 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). All cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.

2.2 Animals and experimental design

HBV transgenic mice (C57BL/6) were gifts from professor Xia Ningshao (Xia Men University, China). The HBV from the transgenic mice belongs to ayw serotype. These mice were housed and maintained under specific pathogen-free condition. In the experiment, the transgenic mice were established in male that weighed 20-25 g, intraperitoneal injections of AGK2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, 82 mg/kg, calculated based on findings of previous studies) in 60% PEG400 + 40% saline or 60% PEG400 + 40% saline alone 18. The serum was collected through tail vein at indicated time points, and the mice were sacrificed at day seven after injection. Then the liver samples were isolated for further examination.

2.3 HBV particles production and HepG2- NTCP cells infection

HBV particles were produced from HepAD38 cells. Briefly, The HepAD38 culture medium was collected and combined with 5% PEG 8000 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by gentle inversion. The mixture was incubated at 4°C overnight and centrifuged at 4000g for 30 mins at 4°C, then a white pellet would be visible. The supernatant was discard and the pellet was resuspended using PBS in 1/100 of the original sample volume. 10ul of the sample was used for real-time PCR to calculate the genome equivalents (mge) of HBV, The rest was stored at -80°C in single-use aliquots. HepG2-NTCP cells infection was performed as previously described, with minor modifications 19. Briefly, cells seeded in collagen-coated 6-well plates with density of 8×105 cells/well, then cultured in PMM medium for 24 h. The cells were then infected with a multiplicity of 500 mge of HBV particles in the presence of 5% PEG8000. After incubation for 20-24 h, the supernatant was discarded and the cells were maintained in PMM medium.

2.4 Cell viability assays

MTS assay was applied to detect the toxic effects of AGK2 on hepatocytes in vitro. Briefly, 1.5×104 cells was seed in each bottle of 96-well plate, then treated with various concentrations of AGK2 (5, 10, 20, 40, 80 and 160 μM) for seven days. Medium containing AGK2 was changed every three days. Viable cells were detected by MTS Reagent (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.5 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for HBV viral antigens

The expression levels of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in cell supernatants and mice serum were evaluated by using an ELISA kit (Wantai, Beijing, China).

2.6 Real-time PCR

HBV replicative intermediates in cultured cells, HBV DNA in mice serum and livers were detected by using Fast Start Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Serial dilutions of HBV DNA plasmids were used to standardize the results. Relative quantification of HBV total RNAs and 3.5kbRNA were conducted by using Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, California, USA), and β-actin mRNA was used as an internal standard for quantification. The 2-ΔΔCt method was used to analyse the fold change of target genes. The primer sequences used in real-time PCR reaction: HBV replicative intermediates: forward primer: 5'-CCTAGTAGTCAGTTATGTCAAC-3', reverse primer: 5'-TCTATAAGCTGGAGGAGTGCGA-3'. Mouse serum and hepatic HBV DNA: forward primer: 5'-CCTCTTCATCCTGCTGCT-3', reverse primer: 5'-AACTGAAAGCCAAACAGTG-3'. HBV total RNAs: forward primer: 5'-ACCGACCTTGAGGCATACTT-3', reverse primer: 5'-GCCTACAGCCTCCTAGTACA-3'. HBV 3.5kb mRNA: forward primer: 5'-GCCTTAGAGTCTCCTGAGCA-3', reverse primer: 5'- GAGGGAGTTCTTCTTCTAGG-3'. β-actin: forward primer: 5'-CTCTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCCT-3', reverse primer: 5'-AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG-3'.

2.7 Northern blot

HBV RNAs were analyzed according to DIG Northern Starter Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the extracted RNA was separated by 1.4% formaldehyde-agarose gel and was stained with ethidium bromide to evaluate the quality of the target RNA under UV light. Then the RNA was transferred on a nylon membrane. After pre-hybridization, the membrane was hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe overnight at 68℃. Next day the membrane was incubated in blocking solution and antibody solution at 37°C for 30 minutes, respectively. Finally, the signal was detected by ChampChemi 610 (Sagecreation, Beijing, China).

2.8 Southern blot

In order to detect the HBV DNA replicative intermediates, the samples were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and denatured by alkali solution. Then the DNA was transferred to the nylon membrane by capillary syphon and fixed by UV cross-linking. Then the membranes were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled full-length HBV riboprobe. After incubated with the anti-digoxin secondary antibody, The membranes were exposed to Carestream X-OMAT BT Film (Carestream, Shanghai, China).

2.9 Western blot

Tissues or cells were lysed by using an appropriate volume of RIPA lysis buffer. After determining the protein concentration, 30 μg protein was denatured through heating, subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 12% gel, then transferred to PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). The membrane was blocked and incubated with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The next day after washed with TBS-T, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The blots were then visualized by ECL (Millipore, Massachusetts, USA).

2.10 Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean±SD. Statistics performed with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (* p<0.05). All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 software.

3. Results

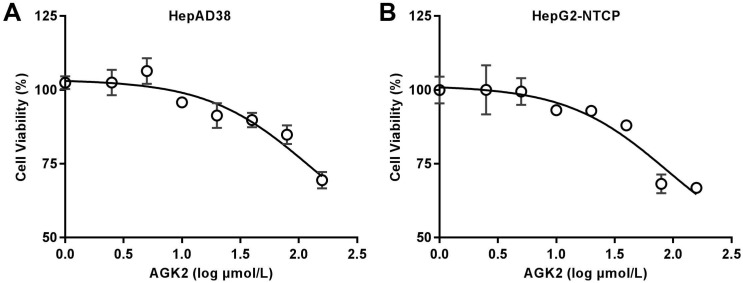

3.1 Minimal cytotoxicity of AGK2 on hepatoma cells

Before the exploration of AGK2 in HBV infection, we first detected whether AGK2 has an inhibition of cell viability by MTS assay. HepAD38 cells, which has stable integration of the HBV genome with HBV replication under the control of tetracycline, were first incubated in medium with different concentrations of AGK2 for seven days. The result showed that AGK2 only has minimal cytotoxicity even at the high concentrations (Fig. 1A). Then, the similar assay also conducted in HepG2-NTCP cells which is the HBV infection model. As expected, AGK2 had little effect on cell viability in HepG2-NTCP cells (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

Cytotoxic effects of AGK2 in the HepAD38 and HepG2-NTCP cell lines. (A-B) 1.5×104 cells were plated in each well of 96-well plate, then cultured in medium with the indicated concentration of AGK2, Medium containing AGK2 was changed every three days. Cell viability was assessed by MTS assays at the seventh day.

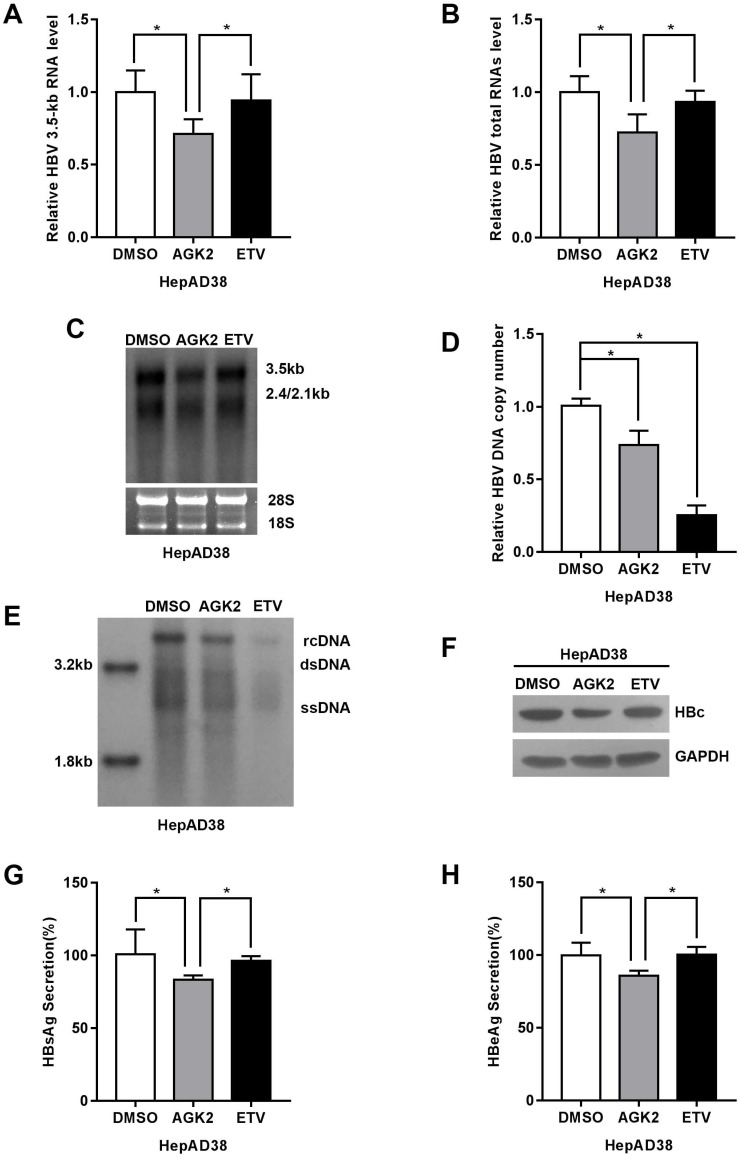

3.2 AGK2 inhibited HBV replication in HBV stably expressing cells

To elucidate the effect of AGK2 on hepatitis B virus replication in vitro, the HepAD38 cells were treated with AGK2 at the concentration of 10μM, and Entecavir (25nM) was used as positive control. After treatment for seven days, total RNAs and 3.5kb RNA was extracted and subjected to real-time PCR. The HBV RNAs include 0.7kb X mRNA, 2.4kb and 2.1kb surface protein mRNAs, 3.5kb precore (pc) RNA and pregenomic (pg) RNA. Interestingly, AGK2 decreased HBV 3.5kb and total RNAs in HepAD38 cells (Fig. 2A-2B). Consistently, Northern blot confirmed that AGK2 inhibited HBV 3.5kb and 2.4/2.1kb RNAs. (Fig. 2C). Real-time PCR and Southern blot also showed that HBV DNA replicative intermediates in cells were reduced (Fig. 2D-2E). Furthermore, HBV core protein (HBc) was detected by Western blot, and the expression levels of HBsAg and HBeAg in cell supernatants were determined by ELISA. Consistently, AGK2 also inhibited the HBc expression, as well as HBsAg and HBeAg secretions. (Fig. 2F-2H).

Fig 2.

AGK2 inhibited HBV replication in HepAD38 cell line. (A-B) HepAD38 cells were cultured with AGK2 (10μM) for seven days, and Entecavir (25nM) was used as positive control. The cells total RNA was extracted and the HBV 3.5kb RNA, total RNAs were analyzed via real-time PCR. The mRNA level of β-actin was used as an internal standard for quantification. *p <0.05. (C) Northern blot was applied to determine the HBV mRNA level. The rRNA level of 28s/18s was used as an internal standard. (D-E) HBV DNA replicative intermediates were extracted and subjected to absolute quantification PCR and Southern blot analysis, *p<0.05. (F) Western blot analyzed the HBc expression after seven days treatment, GAPDH was used as an internal standard. (G-H) HBsAg and HBeAg ELISA was used to screen culture supernatants, *p<0.05.

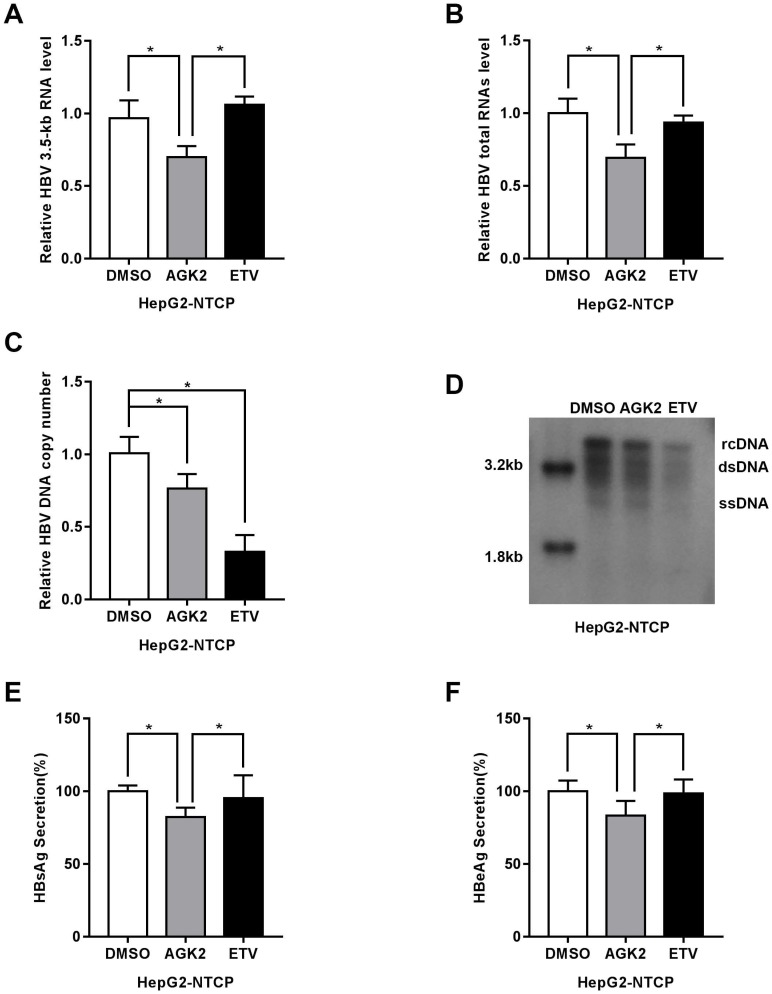

3.3 AGK2 inhibited HBV replication in HBV infection model cells

Recently, sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) was identified as a functional receptor for HBV, and HepG2-NTCP cells which stably express sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide are susceptible to HBV infection. We further test the effect of AGK2 on HBV in this infection cell model. After infected with HBV particles, the HepG2-NTCP cells were treated with AGK2 for seven days. In line with the previous results, HBV 3.5kb, total RNAs and HBV DNA replicative intermediates were decreased in AGK2-treated HepG2-NTCP cells (Fig. 3A-3D). Furthermore, the expression levels of HBsAg and HBeAg also downregulated after the treatment of AGK2 (Fig. 3E-3F). Together, these data as described above indicated that AGK2 could inhibit HBV replication in vitro.

Fig 3.

AGK2 inhibited HBV replication in HepG2-NTCP cell line. (A-B) After infected with HBV, HepG2-NTCP cells were treated with AGK2 (10μM) for seven days, and Entecavir (25nM) was used as positive control. Real-time PCR analysis of HBV mRNA expression, *p<0.05. (C-D) The absolute quantification PCR and Southern blot were performed to determine the copies of HBV replicative intermediates, *p<0.05. (E-F) ELISA were used to assess the expression levels of HBsAg and HBeAg, *p<0.05.

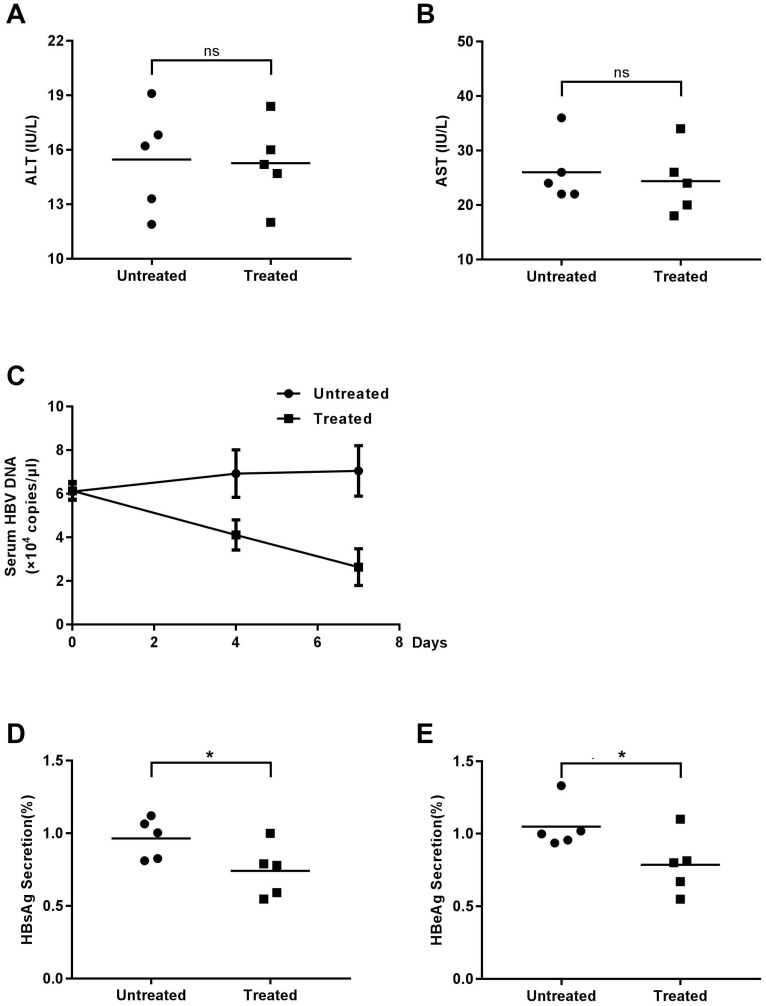

3.4 AGK2 inhibited HBV replication in transgenic mice

Although AKG2, demonstrated the inhibitory effect on HBV replication in HBV stably expressing cells as well as HBV infection model cells, its functional implications in vivo are still unknown. Thus, we used HBV-transgenic mice to study the effect of AGK2 on HBV replication in vivo. The mice were classified into two groups (experimental group and control group) randomly and injected with AKG2 or 60% PEG400 + 40% saline alone via abdomen, respectively. Mouse-serum samples were collected at day zero, four and seven after injection. All of the mice were sacrificed at seventh days, and the liver was isolated for further experiments. To determine the possible toxic effects of AGK2 to the liver, the mice serum alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) were measured. The results showed that the levels of ALT and AST were no differed significantly between the two groups (Fig. 4A-4B), indicating AGK2 had no distinct effect on liver damage.

Fig 4.

The effect of AGK2 on serologic indicators. The mice were randomly assigned to two groups of 5 individuals per group and subjected to intraperitoneal injections of AGK2 diluted in 60% PEG400 + 40% saline or 60% PEG400 + 40% saline alone. (A-B) Serum samples at seven days were collected to detect ALT and AST by microplate modified Reit's method. (C) At zero, four, seven days after injection, the serum samples were collected, and serum HBV DNA was measured by absolute quantification PCR. (D-E) The expression levels of serum HBsAg and HBeAg were detected by ELISA.

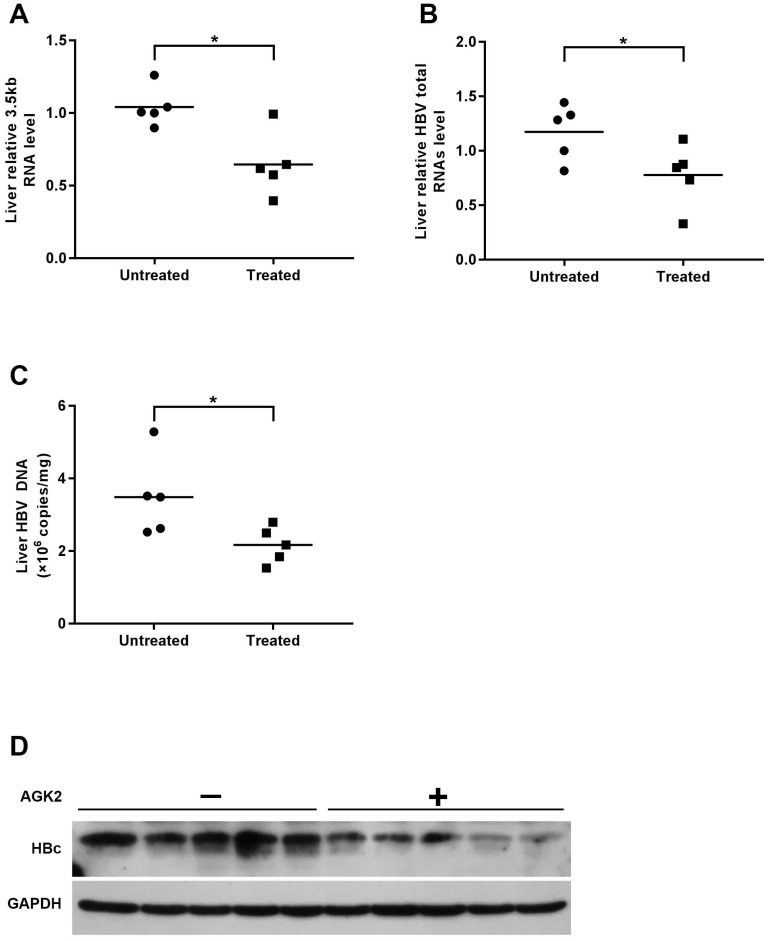

Then, we determined the HBV DNA level in mice serum by using real-time PCR. Compared with the control group, the level of HBV DNA in AGK2-treated group was decreased in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4C). In line with the HBV DNA level, serums HBsAg/HBeAg levels also decreased when treated with AGK2 (Fig. 4D-4E). In addition, HBV 3.5kb RNA and total RNAs were extracted from mouse liver tissues, and the results revealed that AKG2 treatment decreased the level of HBV 3.5kb RNA and total RNAs relative to the control mice (Fig. 5A-5B). Then hepatic HBV DNA level was further analyzed, consistently, AGK2 treatment resulted in decreased HBV DNA in mouse liver tissues (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the result of Western blot also showed that HBc in AGK2 treated-group was lower than that in 60% PEG400 + 40% saline alone group (Fig. 5D). Collectively, these data indicated that AGK2 had an inhibition effect on HBV replication in vivo.

Fig 5.

AGK2 inhibited intrahepatic HBV virus in the transgenic mice. The mice were sacrificed at day seven after injection, and livers were isolated for extraction of HBV DNA, RNA and protein. (A-B) Relative real-time PCR was subjected to detect the HBV 3.5kb RNA and total RNAs levels, the mRNA level of β-actin was used as an internal control, *p <0.05. (C) Hepatic HBV DNA was analyzed by absolute quantification PCR, *p <0.05. (D) The expression of HBc was estimated by western blot.

4. Discussion

As known that IFN treatment is expensive and has severe side effects for the patient, which promotes the application of NAs. However, the long-term treatment of NAs is susceptible to viral resistance, leading to treatment failure. Considering the above issue that both IFN and NAs have its limitation in HBV therapy, the new target for HBV treatment in clinical is urgent.

Silent information regulator 2, or sirtuins are a class of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) dependent protein deacetylases including SIRT1-7 which have been shown to influence a number of cell functions, including gene expression, DNA repair, cell cycle, apoptosis, inflammation, stress response and metabolism 9, 20. Recent researches have shown that sirtuins are associate with HBV replication. It has reported that SIRT1 could up-regulate transcription factor AP-1 and then enhance HBV core promoter activity, ultimately augment HBV replication 21. SIRT3 could protect cells which express HBx from oxidative damage, and possibly influence HBV replication through reducing cellular ROS level 22. The above researches suggest that sirtuins may be molecular targets for controlling HBV replication.

Nicotinamide, a sirtuins inhibitor, has been reported to have a robust anti-HBV activity by inhibiting the function of four HBV promoters 23. However, it is a non-selective sirtuins inhibitor, which leads to hardly to pinpoint which sirtuin is a suitable target for treating HBV. Thus, studying the sirtuin selective inhibitors would make for estimating the anti-HBV therapeutic potential of targeting sirtuins. Based on our recent find that SIRT2 could facilitate HBV transcription and replication 14, we hypothesized that suppression of SIRT2 would have potential antiviral activity. Up to now, several SIRT2 inhibitors have been discovered. Including Thiomyristoyl, AK-1, AK-7, Cambinol, Tenovin-6 and AGK2. Among the inhibitors of SIRT2, AGK2 has an excellent selectivity. It inhibits SIRT2 with IC50 of 3.5 μM, but inhibits SIRT1 and SIRT3 with IC50 of 30 and 91 μM, respectively 24. Moreover, previous studies have shown that SIRT2 inhibition by administration of AGK2 could rescue α-synuclein toxicity and alter inclusion morphology in Parkinson's disease cell model 15. Treatment with AGK2 to inhibit SIRT2 also made intracellular ATP level decrease dramatically which induced by H2O2, leading to PC12 cells necrosis without influencing autophagy, and induced the caspase-3-dependent apoptosis in C6 glioma cells 16, 25. These studies demonstrate the applicability of AGK2. In our study, we found that under the administration of AGK2, the HBV mRNA and HBV DNA replicative intermediates decreased significantly. AGK2 treatment also reduced the amount of HBc protein and the secretion of HBeAg and HBsAg both in HBV stable expressing cells and HBV infection model cells. Moreover, the anti-HBV effect of AGK2 in vivo was further validated in the HBV transgenic mice.

Different from NAs, the representative HBV reverse Polymerase inhibitors, AGK2 might be a novel therapeutic strategy for HBV infection as well as its associated diseases. Meanwhile, further research is needed to clarify the mechanism of anti-HBV of AGK2. In our study, we found AGK2 inhibit HBV mRNA most prominently. Thus, we hypothesize that AGK2 may inhibit HBV replication at the level of transcription. Intriguingly, Yanze et al. reported that SIRT2 inhibition causes p38 MAPK activation, followed by down-regulation of p300 through phosphorylation-mediated degradation pathway 26. Another study of Belloni et al. showed that p300 recruited onto HBV minichromosome and led it bound histones acetylated. When p300 recruitment impaired, HBV minichromosome transcribed significantly less HBV mRNA 27. Thus, whether AGK2 anti-HBV effect depends on p38 MAPK - p300 pathway needs to be determined in future studies.

In conclusion, we identified here a selective SIRT2 inhibitor, AGK2, which inhibited HBV replication in vitro and in vivo. This research shows that AGK2 may be a potential drug in the treatment of chronic HBV infection.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81672012, JC), Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (cstc2016jcyjA0183, JC), The scientific research project of graduate students of Chongqing (CYS17156). The scientific research project of graduate students of Chongqing Medical University (BJRC201725).

References

- 1.Ganem D, Prince AM. Hepatitis B virus infection-natural history and clinical consequences. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;350:1118–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30:2212–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:1546–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Summers J, Mason WS. Replication of the genome of a hepatitis B-like virus by reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate. Cell. 1982;29:403–15. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon H, Lok AS. Hepatitis B therapy. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2011;8:275–84. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papatheodoridis GV, Manolakopoulos S, Dusheiko G, Archimandritis AJ. Therapeutic strategies in the management of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2008;8:167–78. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Micco L, Peppa D, Loggi E, Schurich A, Jefferson L, Cursaro C. et al. Differential boosting of innate and adaptive antiviral responses during pegylated-interferon-alpha therapy of chronic hepatitis B. Journal of hepatology. 2013;58:225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoulim F, Locarnini S. Hepatitis B virus resistance to nucleos(t)ide analogues. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1593–608. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.063. e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michan S, Sinclair D. Sirtuins in mammals: insights into their biological function. The Biochemical journal. 2007;404:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HS, Vassilopoulos A, Wang RH, Lahusen T, Xiao Z, Xu X. et al. SIRT2 maintains genome integrity and suppresses tumorigenesis through regulating APC/C activity. Cancer cell. 2011;20:487–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serrano L, Martinez-Redondo P, Marazuela-Duque A, Vazquez BN, Dooley SJ, Voigt P. et al. The tumor suppressor SirT2 regulates cell cycle progression and genome stability by modulating the mitotic deposition of H4K20 methylation. Genes & development. 2013;27:639–53. doi: 10.1101/gad.211342.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eskandarian HA, Impens F, Nahori MA, Soubigou G, Coppee JY, Cossart P. et al. A role for SIRT2-dependent histone H3K18 deacetylation in bacterial infection. Science. 2013;341:1238858. doi: 10.1126/science.1238858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Chan AW, To KF, Chen W, Zhang Z, Ren J. et al. SIRT2 overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transition by protein kinase B/glycogen synthase kinase-3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Hepatology. 2013;57:2287–98. doi: 10.1002/hep.26278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng ST, Ren JH, Cai XF, Jiang H, Chen J. HBx-elevated SIRT2 promotes HBV replication and hepatocarcinogenesis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications; 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Outeiro TF, Kontopoulos E, Altmann SM, Kufareva I, Strathearn KE, Amore AM. et al. Sirtuin 2 inhibitors rescue alpha-synuclein-mediated toxicity in models of Parkinson's disease. Science. 2007;317:516–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1143780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He X, Nie H, Hong Y, Sheng C, Xia W, Ying W. SIRT2 activity is required for the survival of C6 glioma cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;417:468–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrilli A, Bott M, Fernandez-Valle C. Inhibition of SIRT2 in merlin/NF2-mutant Schwann cells triggers necrosis. Oncotarget. 2013;4:2354–65. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao T, Alam HB, Liu B, Bronson RT, Nikolian VC, Wu E. et al. Selective Inhibition of SIRT2 Improves Outcomes in a Lethal Septic Model. Current molecular medicine. 2015;15:634–41. doi: 10.2174/156652401507150903185852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan R, Zhang Y, Cai D, Liu Y, Cuconati A, Guo H. Spinoculation Enhances HBV Infection in NTCP-Reconstituted Hepatocytes. PloS one. 2015;10:e0129889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi JE, Mostoslavsky R. Sirtuins, metabolism, and DNA repair. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2014;26:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren JH, Tao Y, Zhang ZZ, Chen WX, Cai XF, Chen K. et al. Sirtuin 1 regulates hepatitis B virus transcription and replication by targeting transcription factor AP-1. Journal of virology. 2014;88:2442–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02861-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren JH, Chen X, Zhou L, Tao NN, Zhou HZ, Liu B. et al. Protective Role of Sirtuin3 (SIRT3) in Oxidative Stress Mediated by Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Expression. PloS one. 2016;11:e0150961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li WY, Ren JH, Tao NN, Ran LK, Chen X, Zhou HZ. et al. The SIRT1 inhibitor, nicotinamide, inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vitro and in vivo. Archives of virology. 2016;161:621–30. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2712-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatum PR, Sawada H, Ota Y, Itoh Y, Zhan P, Ieda N. et al. Identification of novel SIRT2-selective inhibitors using a click chemistry approach. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2014;24:1871–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nie H, Chen H, Han J, Hong Y, Ma Y, Xia W. et al. Silencing of SIRT2 induces cell death and a decrease in the intracellular ATP level of PC12 cells. International journal of physiology, pathophysiology and pharmacology. 2011;3:65–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Matsumori H, Nakayama Y, Osaki M, Kojima H, Kurimasa A. et al. SIRT2 down-regulation in HeLa can induce p53 accumulation via p38 MAPK activation-dependent p300 decrease, eventually leading to apoptosis. Genes to cells: devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 2011;16:34–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belloni L, Pollicino T, De Nicola F, Guerrieri F, Raffa G, Fanciulli M. et al. Nuclear HBx binds the HBV minichromosome and modifies the epigenetic regulation of cccDNA function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:19975–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908365106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]