Abstract

Background:

Prioritisation of end-of-life care by policymakers has been the subject of extensive rhetoric, but little scrutiny. In England, responsibility for improving health and care lies with 152 regional Health and Wellbeing Boards.

Aim:

To understand the extent to which Health and Wellbeing Boards have identified and prioritised end-of-life care needs and their plans for improvement.

Design:

Qualitative documentary analysis of Health and Wellbeing Strategies. Summative content analysis to quantify key concepts and identify themes.

Data sources:

Strategies were identified from Local Authority web pages and systematically searched to identify relevant content.

Results:

In total, 150 strategies were identified. End-of-life care was mentioned in 78 (52.0%) and prioritised in 6 (4.0%). Four themes emerged: (1) clinical context – in 43/78 strategies end-of-life care was mentioned within a specific clinical context, most often ageing and dementia; (2) aims and aspirations – 31 strategies identified local needs and/or quantifiable aims, most related to the place of death; (3) narrative thread – the connection between need, aim and planned intervention was disjointed, just six strategies included all three components; and (4) focus of evidence – where cited, evidence related to evidence of need, not evidence for effective interventions.

Conclusion:

Half of Health and Wellbeing Strategies mention end-of-life care, few prioritise it and none cite evidence for effective interventions. The absence of connection between need, aim and intervention is concerning. Future research should explore whether and how strategies have impacted on local populations.

Keywords: Palliative care, terminal care, policy, evidence, evidence-based medicine, qualitative

What is already known about the topic?

End-of-life care has been highlighted as a priority for policymakers nationally and internationally, but the extent to which this has been acted upon has not been systematically examined.

Policymakers are expected to base decisions on academic evidence; how evidence is used in relation to end-of-life care is unknown.

What this paper adds?

This is the first study to systematically analyse content relating to end-of-life care within local health care strategies, providing a comprehensive national picture of priorities and plans.

Half of local strategies in England did not mention end-of-life care; just 4% included end-of-life care as a priority area.

There was sparse use of evidence in relation to end-of-life care, particularly with respect to the effectiveness of interventions.

There was a lack of connection between identification of local end-of-life care needs, relevant targets and interventions.

There was a reliance on the place of death for quantifying need.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Academic engagement with policymakers is needed to frame evidence relating to end-of-life care in such a way that it is timely, important, relevant and easy to use.

A more diverse array of metrics relating to end-of-life care, including for high-priority groups, should be provided at the local level.

Future research should investigate why some areas prioritised end-of-life care more than others, and whether and how strategies have impacted on local populations.

Introduction

The presence of a national government–led strategy for palliative and end-of-life care has been suggested as an important driver of the quality of care of the dying.1 In the United Kingdom, the first government-led End of Life Care Strategy was published in 2008.2 However, since then numerous high-profile reports including the Neuberger review into the Liverpool Care Pathway,3 the Ombudsman’s report Dying Without Dignity,4 the Health Select Committee report on end-of-life care5 and the Care Quality Commission review of inequalities near the end of life6 have highlighted the consequences of inadequate and highly variable end-of-life care services.

In 2012, the health care system in England underwent a process of radical reform through the Health and Social Care act, which devolved planning for and delivery of health and social care to the local level. This was achieved through the establishment of Health and Wellbeing Boards, statutory committees of each of the 152 upper-tier Local Authorities in England, designed to bring together the health and care system to improve the health and wellbeing of the local population. To do this, Health and Wellbeing Boards were required to produce a Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy, setting out how the local population’s needs should be met by commissioners, with a core aim of developing ‘local evidence-based priorities for commissioning’.7

There are compelling reasons for end-of-life care to be a priority for local policymakers. It is estimated that 75% of those who die would benefit from palliative care,8 and the need for palliative care is projected to increase 42% by 2040 due to population ageing.9 International evidence shows that access to services can improve outcomes near the end of life, for example, people who receive support from a specialist palliative care team are more likely to die at home and less likely to attend Emergency Departments close to death.10,11 In addition, there is a strong economic argument for investment in end-of-life care services, which are frequently cost neutral or cost saving.12 However, there are currently large variations in commissioning of specialist palliative care services: in England budgets for specialist palliative care services range from £51.83 to £2329.19 per patient per annum.13

Prioritisation of end-of-life care by policymakers has been the subject of extensive rhetoric.14–17 Whether and how this has been achieved at the local level has not been scrutinised. Devolution of responsibility for health and care to the local level provides an opportunity to examine how end-of-life care is prioritised and to identify opportunities for improvement. The aim was to understand the extent to which Health and Wellbeing Boards have identified end-of-life care needs in their local populations, and their priorities and plans for improvement.

Methods

Design

Qualitative documentary analysis.

Data acquisition

Health and Wellbeing Strategies were identified from searches of Local Authority web pages. We were interested in the first strategies, published from 2012 onwards, to facilitate comparison across different areas. If the first strategy could not be identified, an email was sent to the Health and Wellbeing Board. Non-response was followed up by a further email. Searches and correspondence occurred between May 2017 and October 2017.

Data extraction

Strategies were systematically searched electronically for key terms to identify content relating to end-of-life care (palliat*, end of*, terminal, bereave*, death, die, dying). Content where key terms were mentioned in a context that did not relate specifically to end-of-life care (e.g. ‘winter deaths’), or those that mentioned these terms only in the context of the life course (e.g. ‘from birth to end of life’) without further focus on end-of-life care, was not included.

Where strategies did not include any reference to end-of-life care, this was confirmed by two authors (K.E.S. and J.L.-M.). Where end-of-life care was included, the relevant sections were printed to produce a resource folder from which familiarisation of the data occurred. Qualitative software was not used as we wanted to preserve the original format, enabling distinction between the appearance of key terms in the main text and in figures. The relevant section of each strategy was read in detail by K.E.S. and J.L.-M.

Following familiarisation and a pilot study focussing on one area (London), a data extraction form was devised. Information extracted included timescale of the strategy, total number of pages in the strategy, inclusion in the strategy of any mention of key terms relating to end-of-life care, number of pages that included a mention of end-of-life care, prioritisation of end-of-life care (named as a priority area or strategic objective, or focus area), identification of a specific clinical context within which end-of-life care was mentioned, identification of evidence of need for improved end-of-life care, identification of a target for improvement and identification of a specific intervention for improving end-of-life care or link to an existing local end-of-life care strategy.

Data analysis

Summative content analysis was used to quantify key concepts and identify themes. In summative content analysis, data analysis begins with systematic searches to quantify the occurrence of specific words or phrases, forming the basis for exploration of the data.18 This then allows for examination of the contextual use of these words and phrases, and further interpretation of the data. Summative content analysis is particularly useful when the aim is to summarise the content of qualitative data, such as documents and texts, for example, previous studies have used this approach to examine death and bereavement in nursing textbooks.19

An iterative process of analysis and discussion of each strategy informed the development of themes. Following a deductive analysis to identify ‘cases’ (strategies that did include reference to end-of-life care), more inductive and exploratory analyses were undertaken to consider the context and detail of each case. Following analysis of all strategies, themes and subthemes were refined in line with the study aims. Initial coding was undertaken by K.E.S. and J.L.-M., and any discrepancies were resolved in discussion between the analysis team (K.E.S., J.L.-M. and K.B.).

Results

In total, 150 Health and Wellbeing Strategies were identified, covering all 152 Health and Wellbeing Boards (Appendix 1). There were two strategies that each included two Health and Wellbeing Board areas. The 150 strategies comprised a total of 4229 pages (mean 28.2, range 1–92). Most started in 2012 (35) or 2013 (92). Seven commenced in 2014 and one in 2015. In 15 there was no start date.

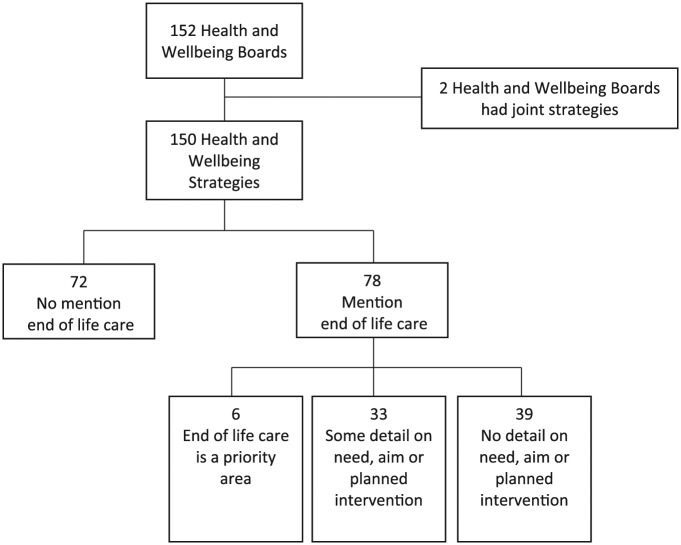

Of the 150 strategies identified, 72 (48.0%) contained no mention of any end-of-life care key terms (Figure 1). For the 78 strategies that did mention end-of-life care, the most common term identified was ‘end of*’ (either ‘end of life’ or ‘end of their lives’) a total of 245 uses in 70 strategies. There were 180 uses of terms ‘death’, ‘dying’ or ‘die’ in 48 strategies. The term ‘palliat*’ was used 16 times in 11 strategies, ‘bereave*’ was used 10 times in six strategies and ‘terminal’ five times in five strategies.

Figure 1.

Prioritisation of end-of-life care within Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies. A total of 150 Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies were identified, covering all 152 Health and Wellbeing Boards in England. Of these, 72 (48.0%) contained no mention of any end-of-life care key terms. Of the 78 strategies that mentioned end-of-life care, 39 (50.0%) included no information on local needs, aims or planned interventions. Six strategies (4.0% total) included end-of-life care as a priority area.

The extent to which end-of-life care was prioritised within the 78 strategies was highly variable. The number of pages that mentioned end-of-life care ranged from 1 to 8 (mean 2.4 pages). Six strategies (4.0% total) included end-of-life care as one of their main priorities. In contrast, 39 of 78 strategies that mentioned end-of-life care included no contextual information on local need, an aim or target, or any specific plans for improvement. For example, in one strategy ‘End of Life Care’ was written in a figure, without any further detail in the text (strategy 89). Another strategy mentioned ‘Supporting a good death for everyone’ but without any further information on how this might be achieved (strategy 65).

Four themes emerged from the data, regarding the context of end-of-life care, documentation of the aims and/or aspirations, narrative thread between needs and outcomes, and inclusion of evidence.

Context

This theme related to the clinical context within which end-of-life care was mentioned.

In 43 of 78 strategies, end-of-life care was mentioned within a specific clinical context, and in 29 of these the clinical context was exclusive: end-of-life care was not mentioned outside this context. The clinical context was most often related to ageing and older people (27 strategies) and dementia (15 strategies). In these strategies, end-of-life care was usually mentioned as one part of an overall priority for this clinical group. For example, in one strategy with a priority on dementia: ‘An integrated care pathway for dementia is being developed … from raising awareness and early intervention, right through to end of life support’ (strategy 110).

Two strategies mentioned end-of-life care within the context of support for carers, one in the context of children’s palliative care and one strategy mentioned end-of-life care in the context of cancer. Three strategies had more than one clinical context.

Aims and aspirations

This theme contained two subthemes: identification of need and identification of targets for improvement.

Strategies frequently included general aspirations to improve end-of-life care, using abstract concepts such as ‘dignity’, ‘support’, ‘respect’ and ‘choice’ (e.g. ‘make sure people are supported and treated with dignity and respect at the end of their lives’, strategy 108). No strategy quantified the level of need or identified a target with respect to these aspirations.

Identification of need

Quantifiable outcomes were both less common and less variable. A total of 21 strategies quantified local end-of-life care need, in all cases this was related to the place of death: 14 strategies cited the local home death rate, 8 the percentage of hospital deaths and 3 other aspects of place of death; 10 of these 21 strategies included a geographical comparison for context, for example, comparing the local proportion of home deaths with another region (either local or national), and 5 included the temporal context, for example, indicating that home deaths are rising in the local area.

Identification of targets for improvement

A total of 19 strategies included one or more quantifiable aims relating to end-of-life care. Again, these most commonly related to the place of death (in 18 strategies). Seven strategies identified increasing home and care home deaths as a target, four identified reducing hospital deaths and nine identified other aspects of the place of death. Strategies commonly used words such as ‘increase’ and ‘decrease’ with respect to these aims; however, few strategies identified specific numerical targets.

Four of these 19 strategies included aims that were not related to the place of death: in two the number of people with end-of-life or advance care plans, in one the number of people on an Electronic Palliative Care Coordination System and in one plans to measure bereaved carers’ views of quality of end-of-life care and the number of patients on ‘appropriate recognised care pathways’.

Strategies that mentioned end-of-life care within a specific clinical context (such as ageing or dementia) were less likely to include evidence of need or targets than those that mentioned end-of-life care in general contexts. Of the 29 strategies with an exclusive clinical context, four identified a need and just three included a target.

Narrative thread

Overall, the connection between need, aim and intervention was disjointed.

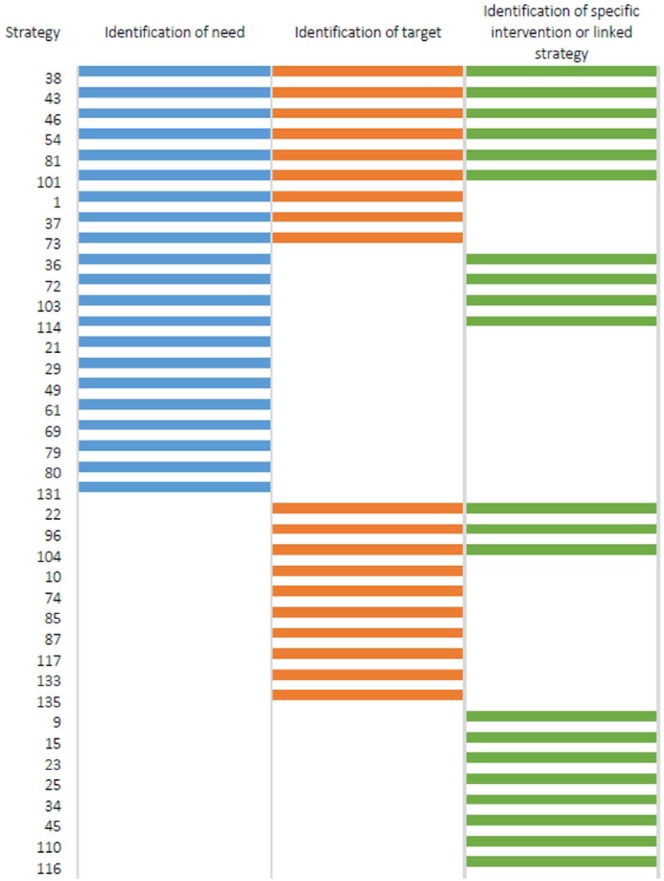

Of the 78 strategies, 39 identified one or more of the following: evidence of need (21 strategies), a target (19 strategies) and a specific intervention or linked strategy for improvement (21 strategies). Only six included all three elements (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Theme 3 – disjointed narrative thread. Of the 150 Health and Wellbeing Strategies, 39 cited one or more of the following: evidence of need (21 strategies), an aim or target (19 strategies) and a specific intervention or linked strategy for improvement (21 strategies). Six Health and Wellbeing Strategies included all three elements.

Of the 21 strategies that cited evidence of need, 9 strategies identified a related aim or target and 10 identified specific interventions or linked strategies. Specific interventions included the Gold Standards Framework, named Electronic Palliative Care Coordination Systems, and regionally developed End of Life Models and Charters. The rationale for these specific interventions was not usually given, and no strategy highlighted the likely expected improvement in outcomes from implementing these specific interventions.

A further 8 of these 21 strategies mentioned non-specific aspirational plans to improve end-of-life care. These included ‘Empower and enable people to make positive choices’, ‘Ensure that community based services are in place’, ‘Encourage and provide a system for families and carers to feedback their experiences’ and ‘Ensure that palliative care services are integrated’ (strategies 73, 37, 79 and 131). There was no indication of how these aspirations might be achieved.

Narrow focus of evidence

Where evidence was cited, this related to evidence of need and not evidence for effective interventions.

Of the 21 strategies that cited evidence of need, few provided a source or reference for the information. Two strategies cited National End of Life Care Profiles, available from NHS England. One strategy cited academic evidence in relation to end-of-life care ‘The Cicely Saunders Institute 2012 study found that 66% of study participants … would prefer to die at home’ (strategy 114), but did not provide a full reference.

No strategy cited evidence in the context of planned interventions.

Discussion

Improving end-of-life care requires not only prioritisation by policymakers, but also strategies that focus on evidence-based interventions and plans for measuring progress. In this qualitative documentary analysis, almost half of Health and Wellbeing Strategies in England included no mention of end-of-life care, and very few included end-of-life care as a priority area. There was a lack of connection between identification of need, relevant targets and interventions for improvement. Even among the six strategies that prioritised end-of-life care, just three identified a need, a target and an intervention. There was sparse use of evidence, particularly in the context of interventions.

Given that the core aim of Health and Wellbeing Strategies is to develop local ‘evidence-based priorities’,7 the sparse use of evidence in them is a concern. Where evidence was used, it was in the context of need, rather than evidence for effective interventions. This may reflect the relative scarcity of interventional compared to observational research, an issue which is not exclusive to end-of-life care.20,21

There was a reliance on the place of death as a measure of need and a target for improvement. This reflects a strong policy focus on the place of death over the past decade.2 This policy focus has been accompanied by a research focus, and there is a growing body of evidence for interventions that reduce death in hospital.10,22 Better dissemination of this evidence to policymakers may be key to improve the narrative thread from the need to intervention. There was less emphasis on the place of death in strategies that focused exclusively on a particular clinical context (e.g. ageing or dementia), which may reflect a paucity of available data for these subgroups.

That only one strategy mentioned end-of-life care in the context of cancer is surprising given the historical association of UK palliative care services with cancer.23 In contrast, end-of-life care was frequently mentioned in the context of ageing and dementia, which is encouraging in light of the projected increase in population palliative care needs in these groups.9

While Health and Wellbeing Strategies have existed since 2012, they have been subject to little academic scrutiny. A previous study of 50 Health and Wellbeing Strategies found that they varied widely in timescale, length and structure, and had inadequate focus on evidence.24 Other studies have examined Health and Wellbeing Board activity from the perspective of a specific clinical area. An exploration of mental health coverage in Health and Wellbeing Strategies found that 91% included at least one area of mental health and 46% set mental health as a standalone priority.25

Strengths and limitations

We believe our study is the first to systematically analyse prioritisation of end-of-life care within local health care strategies, providing a comprehensive national picture of priorities and plans. All 150 Health and Wellbeing Strategies were analysed. However, this method cannot inform us about the context in which strategies were developed, about why variation occurs or about how these strategies are being used.24 At the time of analysis, some Health and Wellbeing Boards had published follow-on strategies, which were not examined. It would be interesting to compare the first with subsequent strategies. Some Health and Wellbeing Strategies indicated the presence of a separate end-of-life care strategy. It was beyond the scope of this study to examine these in detail, and therefore we adopted an inclusive approach such that these were included with ‘specific interventions’ to improve care.

Conclusion

Despite high-profile calls for prioritisation of end-of-life care, our study shows that only half of Health and Wellbeing Strategies mention end-of-life care and few indicate what should be improved or how this will happen. Engagement with policymakers around the importance of the narrative thread from need to intervention would be valuable. Further research is needed to explore why some areas prioritised end-of-life care more than others and to examine whether and how local strategies have influenced outcomes at the end of life.

Although the core aim of Health and Wellbeing Strategies is to develop evidence-based priorities for commissioning, there is scant use of evidence with respect to end-of-life care. Academic engagement with policymakers is needed to frame appropriate evidence in such a way that it is timely, important, relevant and easy to use. Building relationships with policymakers, and understanding policymakers’ priorities, is key.26,27

The identification of targets for improvement is constrained by available data, which in England has focused on the place of death. Providing local policymakers with a more diverse array of metrics would enable a broader focus for improvement. For example, in England additional metrics have been proposed to include Emergency Department attendance and time spent in hospital in the last months of life.28 These data should be available for high-priority groups such as older people and those with dementia, to enable policymakers to identify their specific needs and plan services accordingly.

Documentary analysis of health care strategies can be a valuable tool to highlight areas of inequality and drive change.29,30 For example, such analyses have been used to examine palliative care content in national dementia strategies.31 These methods have the potential to be adopted more widely to explore the prioritisation of end-of-life care by policymakers, both within and between different health care settings. We recommend that future analyses include assessment of the following elements: (1) identification of local end-of-life care needs, including temporal and geographical trends; (2) identification of numerical targets for improvement with indicative time frames and (3) identification of appropriate interventions, including evidence of effectiveness with respect to the identified target, and the anticipated improvement.

Acknowledgments

K.E.S. and I.J.H. conceived the idea of the study. K.E.S., J.L and K.B. designed the study with input from I.J.H. Data collection and analysis were carried out by K.E.S. and J.L. All authors helped interpret the data. K.E.S. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to subsequent drafts and approved the final paper. Data may be made available on an individual basis following discussion with the corresponding author.

Appendix 1

Table 1.

Structure and content relating to end-of-life care of 150 Health and Wellbeing Board Strategies.

| Strategy number | Region | Start year | End year | Mentions EoL | Total pages in strategy | Total pages mentioning EoL | EoL is a priority | EoL mentioned within a clinical context | The clinical context is exclusive | Identification of need | Need is place of death | Identification of target | Target is place of death | Identification of specific intervention or linked strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EE | 2012 | 2016 | yes | 23 | 4 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| 2 | EE | 2012 | 2016 | no | 18 | |||||||||

| 3 | EE | 2012 | 2017 | no | 30 | |||||||||

| 4 | EE | 2012 | 2015 | no | 9 | |||||||||

| 5 | EE | 2013 | 2015 | yes | 22 | 3 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 6 | EE | 2013 | 2016 | no | 32 | |||||||||

| 7 | EE | 2012 | 2017 | yes | 24 | 4 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 8 | EE | 2013 | 2018 | yes | 24 | 4 | no | yes | no | no | na | no | na | no |

| 9 | EE | 2014 | 2017 | yes | 13 | 3 | no | yes | no | no | na | no | na | yes |

| 10 | EE | 2012 | 2022 | yes | 28 | 2 | no | yes | no | no | na | yes | yes | no |

| 11 | EE | 2013 | 2017 | no | 44 | |||||||||

| 12 | EM | 2012 | 2014 | no | 22 | |||||||||

| 13 | EM | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 40 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 14 | EM | 2013 | 2016 | no | 21 | |||||||||

| 15 | EM | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 13 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | yes |

| 16 | EM | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 33 | 3 | no | yes | no | no | na | no | na | no |

| 17 | EM | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 39 | 4 | no | yes | no | no | na | no | na | no |

| 18 | EM | 2013 | 2018 | no | 26 | |||||||||

| 19 | EM | 2013 | 2016 | no | 16 | |||||||||

| 20 | EM | 2014 | 2017 | no | 12 | |||||||||

| 21 | GL | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 32 | 2 | no | yes | no | yes | yes | no | na | no |

| 22 | GL | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 28 | 3 | no | yes | yes | no | na | yes | yes | yes |

| 23 | GL | yes | 23 | 3 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | yes | ||

| 24 | GL | 2012 | 2015 | no | 15 | |||||||||

| 25 | GL | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 49 | 4 | no | yes | no | no | na | no | na | yes |

| 26 | GL | 2012 | 2013 | no | 16 | |||||||||

| 27 | GL | no | 30 | |||||||||||

| 28 | GL | 2012 | 2015 | no | 34 | |||||||||

| 29 | GL | 2013 | 2018 | yes | 41 | 3 | no | no | na | yes | yes | no | na | no |

| 30 | GL | 2012 | 2016 | no | 30 | |||||||||

| 31 | GL | 2014 | 2019 | no | 44 | |||||||||

| 32 | GL | 2015 | 2018 | no | 24 | |||||||||

| 33 | GL | 2013 | 2014 | no | 16 | |||||||||

| 34 | GL | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 51 | 4 | no | yes | no | no | na | no | na | yes |

| 35 | GL | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 22 | 2 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 36 | GL | 2012 | 2014 | yes | 49 | 6 | no | yes | no | yes | yes | no | na | yes |

| 37 | GL | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 33 | 3 | no | no | na | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| 38 | GL | 2013 | 2017 | yes | 41 | 5 | no | no | na | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 39 | GL | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 19 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 40 | GL | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 60 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 41 | GL | no | 23 | |||||||||||

| 42 | GL | 2013 | 2023 | no | 42 | |||||||||

| 43 | GL | 2013 | 2014 | yes | 65 | 6 | no | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 44 | GL | no | 16 | |||||||||||

| 45 | GL | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 37 | 2 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | yes |

| 46 | GL | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 28 | 6 | no | no | na | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 47 | GL | 2013 | 2014 | yes | 11 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 48 | GL | 2012 | 2013 | no | 28 | |||||||||

| 49 | GL | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 58 | 2 | no | no | na | yes | yes | no | na | no |

| 50 | GL | 2013 | 2015 | yes | 9 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 51 | GL | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 37 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 52 | GL | 2013 | 2015 | no | 21 | |||||||||

| 53 | GL | 2013 | 2023 | no | 24 | |||||||||

| 54 | NE | 2013 | 2017 | yes | 32 | 4 | yes | no | na | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 55 | NE | 2013 | 2016 | no | 29 | |||||||||

| 56 | NE | 2013 | 2018 | yes | 18 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 57 | NE | 2013 | 2023 | no | 21 | |||||||||

| 58 | NE | 2014 | no | 26 | ||||||||||

| 59 | NE | 2013 | 2018 | no | 15 | |||||||||

| 60 | NE | 2012 | 2018 | yes | 32 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 61 | NE | 2013/14 | 2015/16 | yes | 43 | 2 | no | yes | no | yes | yes | no | na | no |

| 62 | NE | 2013 | 2016 | no | 58 | |||||||||

| 63 | NE | 2013 | 2023 | no | 37 | |||||||||

| 64 | NE | 2013 | 2016 | no | 21 | |||||||||

| 65 | NE | yes | 6 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no | ||

| 66 | NW | 2012 | 2015 | no | 92 | |||||||||

| 67 | NW | 2013 | 2015 | no | 27 | |||||||||

| 68 | NW | 2013 | 2014 | yes | 5 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 69 | NW | 2012 | yes | 18 | 1 | no | no | na | yes | yes | no | na | no | |

| 70 | NW | 2013 | 2016 | no | 32 | |||||||||

| 71 | NW | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 32 | 4 | no | yes | no | no | na | no | na | no |

| 72 | NW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 20 | 3 | yes | no | na | yes | yes | no | no | yes |

| 73 | NW | 2013 | 2018 | yes | 35 | 3 | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| 74 | NW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 19 | 3 | no | no | na | no | na | yes | yes | no |

| 75 | NW | 2014 | 2019 | no | 32 | |||||||||

| 76 | NW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 12 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 77 | NW | 2012 | 2015 | no | 17 | |||||||||

| 78 | NW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 39 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 79 | NW | 2013 | 2018 | yes | 47 | 3 | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | na | no |

| 80 | NW | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 51 | 7 | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | na | no |

| 81 | NW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 27 | 5 | yes | no | na | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 82 | NW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 69 | 2 | no | yes | no | no | na | no | na | no |

| 83 | NW | 2013 | 2016 | no | 1 | |||||||||

| 84 | NW | 2013 | 2014 | no | 24 | |||||||||

| 85 | NW | 2013 | yes | 26 | 2 | no | no | na | no | na | yes | yes | no | |

| 86 | NW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 40 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 87 | NW | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 19 | 3 | no | yes | yes | no | na | yes | yes | no |

| 88 | NW | 2016 | no | 9 | ||||||||||

| 89 | SE | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 53 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 90 | SE | yes | 51 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no | ||

| 91 | SE | 2013 | 2016 | no | 25 | |||||||||

| 92 | SE | 2012 | 2017 | no | 40 | |||||||||

| 93 | SE | 2012 | 2015 | yes | 12 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 94 | SE | 2014 | 2017 | no | 22 | |||||||||

| 95 | SE | 2013 | 2016 | no | 23 | |||||||||

| 96 | SE | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 25 | 2 | no | no | na | no | na | yes | no | yes |

| 97 | SE | yes | 20 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no | ||

| 98 | SE | 2013 | 2016 | no | 17 | |||||||||

| 99 | SE | 2013 | 2016 | no | 26 | |||||||||

| 100 | SE | 2013 | 2014 | no | 11 | |||||||||

| 101 | SE | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 20 | 8 | yes | no | na | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 102 | SE | 2013 | 2018 | no | 18 | |||||||||

| 103 | SE | yes | 24 | 3 | no | no | na | yes | yes | no | na | yes | ||

| 104 | SE | 2012 | 2016 | yes | 27 | 3 | no | no | na | no | na | yes | yes | yes |

| 105 | SE | no | 20 | |||||||||||

| 106 | SE | 2013 | 2015 | no | 10 | |||||||||

| 107 | SE | 2013 | 2016 | no | 11 | |||||||||

| 108 | SW | yes | 16 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no | ||

| 109 | SW | 2013 | 2016 | no | 18 | |||||||||

| 110 | SW | 2013 | yes | 16 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | yes | |

| 111 | SW | 2013 | 2015 | no | 32 | |||||||||

| 112 | SW | 2013 | no | 40 | ||||||||||

| 113 | SW | no | 16 | |||||||||||

| 114 | SW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 24 | 3 | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | na | yes |

| 115 | SW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 13 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 116 | SW | 2012/13 | 2014/15 | yes | 26 | 2 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | yes |

| 117 | SW | 2013 | yes | 19 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | yes | yes | no | |

| 118 | SW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 32 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 119 | SW | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 34 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 120 | SW | 2012 | 2032 | no | 23 | |||||||||

| 121 | SW | 2013 | 2018 | no | 13 | |||||||||

| 122 | WM | 2012 | 2013 | no | 54 | |||||||||

| 123 | WM | 2013 | 2014 | no | 29 | |||||||||

| 124 | WM | 2013 | 2016 | no | 9 | |||||||||

| 125 | WM | 2013/14 | 2015/16 | yes | 18 | 2 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 126 | WM | no | 1 | |||||||||||

| 127 | WM | no | 37 | |||||||||||

| 128 | WM | 2013 | 2016 | no | 12 | |||||||||

| 129 | WM | 2012 | 2013 | no | 41 | |||||||||

| 130 | WM | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 35 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 131 | WM | 2013 | 2014 | yes | 53 | 2 | no | no | na | yes | yes | no | na | no |

| 132 | WM | 2013 | 2018 | yes | 63 | 2 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 133 | WM | 2013 | 2018 | yes | 28 | 2 | yes | no | na | no | na | yes | yes | no |

| 134 | WM | yes | 29 | 2 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no | ||

| 135 | WM | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 20 | 2 | no | no | na | no | na | yes | yes | no |

| 136 | Y | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 66 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 137 | Y | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 31 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 138 | Y | 2013 | 2016 | no | 58 | |||||||||

| 139 | Y | 2013 | 2018 | no | 27 | |||||||||

| 140 | Y | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 42 | 2 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 141 | Y | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 22 | 1 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 142 | Y | 2013 | 2017 | yes | 48 | 2 | no | yes | yes | no | na | no | na | no |

| 143 | Y | 2012 | 2022 | no | 30 | |||||||||

| 144 | Y | 2014 | 2020 | no | 16 | |||||||||

| 145 | Y | 2013 | 2015 | no | 8 | |||||||||

| 146 | Y | 2012 | 2015 | no | 9 | |||||||||

| 147 | Y | 2013 | 2018 | no | 38 | |||||||||

| 148 | Y | 2013 | 2016 | no | 16 | |||||||||

| 149 | Y | 2013 | 2016 | yes | 14 | 1 | no | no | na | no | na | no | na | no |

| 150 | Y | 2013 | 2018 | no | 22 |

GL: Greater London; WM: West Midlands; SE: South East; NW: North West; Y: Yorkshire; NE: North East; EE: East England; EM: East Midlands; NE: North East; SW: South West; EoL: end of life; na: not applicable.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was not required as the research method was a documentary analysis of publicly available material.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This report is independent research arising from a Clinician Scientist Fellowship to K.E.S. (CS-2015-15-005) supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

ORCID iDs: Katherine E Sleeman  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9777-4373

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9777-4373

Irene J Higginson  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1426-4923

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1426-4923

Katherine Bristowe  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1809-217X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1809-217X

References

- 1. Economist Intelligence Unit. The 2015 quality of death index: ranking palliative care across the world. London: Economist Intelligence Unit, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health. End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for adults at the end of their life. London: Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health. More care less pathway: a review of the Liverpool Care Pathway. London: Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman. Dying without dignity: investigations by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman into complaints about end of life care. 2015, https://www.basw.co.uk/resources/dying-without-dignity-investigations-parliamentary-and-health-service-ombudsman-complaints

- 5. End of life care: House of Commons Health Committee, 2015. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201415/cmselect/cmhealth/805/805.pdf

- 6. Care Quality Commission. A different ending: addressing inequalities in end of life care. London: Care Quality Commission, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Department of Health. Statutory guidance on joint strategic needs assessments and joint health and wellbeing strategies. London: Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murtagh FE, Bausewein C, Verne J, et al. How many people need palliative care? A study developing and comparing methods for population-based estimates. Palliat Med 2014; 28(1): 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med 2017; 15(1): 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6: CD007760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Henson LA, Gao W, Higginson IJ, et al. Emergency department attendance by patients with cancer in their last month of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(4): 370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith S, Brick A, O’Hara S, et al. Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med 2014; 28(2): 130–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lancaster H, Finlay I, Downman M, et al. Commissioning of specialist palliative care services in England. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017; 8: 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Department of Health. Our commitment to you for end of life care. The government response to the review of choice in end of life care. London: Department of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Care for Palliative Care. Time for action: why end of life care needs to improve and what we need to do next. London: National Care for Palliative Care, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. Sixty-seventh World Health Assembly, 2014, http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21454en/s21454en.pdf

- 17. Prioritising palliative care. Lancet 2014; 383(9930): 1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15(9): 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrell B, Virani R, Grant M, et al. Analysis of content regarding death and bereavement in nursing texts. Psychooncology 1999; 8(6): 500–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Macintyre S. Evidence based policy making. BMJ 2003; 326(7379): 5–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Macintyre S, Chalmers I, Horton R, et al. Using evidence to inform health policy: case study. BMJ 2001; 322(7280): 222–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sleeman KE, Ho YK, Verne J, et al. Reversal of English trend towards hospital death in dementia: a population-based study of place of death and associated individual and regional factors, 2001-2010. BMC Neurol 2014; 14: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sleeman KE, Davies JM, Verne J, et al. The changing demographics of inpatient hospice death: population-based cross-sectional study in England, 1993-2012. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beenstock J, Sowden S, Hunter DJ, et al. Are health and well-being strategies in England fit for purpose? A thematic content analysis. J Public Health 2015; 37(3): 461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scrutton J. A place for parity. Health and wellbeing boards and mental health. London: Centre for Mental Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wye L, Brangan E, Cameron A, et al. Evidence based policy making and the ‘art’ of commissioning – how English healthcare commissioners access and use information and academic research in ‘real life’ decision-making: an empirical qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015; 15: 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, et al. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paper L. National End of Life Care programme board, 2016, http://endoflifecareambitions.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Paper-L-Metrics-for-End-of-Life-Care.pdf

- 29. O’Connor M, Payne S. Discourse analysis: examining the potential for research in palliative care. Palliat Med 2006; 20(8): 829–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Katikireddi SV, Higgins M, Bond L, et al. How evidence based is English public health policy? BMJ 2011; 343: d7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nakanishi M, Nakashima T, Shindo Y, et al. An evaluation of palliative care contents in national dementia strategies in reference to the European Association for Palliative Care white paper. Int Psychogeriatr 2015; 27(9): 1551–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]