Abstract

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) algorithm for detecting presence of serum antibodies against Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV) in subjects with potential infections with the virus has included screening by indirect ELISA against recombinant nucleocapsid (N) protein and confirmation by immunofluorescent staining of infected monolayers and/or microneutralization titration. Other international groups include indirect ELISA assays using the spike (S) protein, as part of their serological determinations. In the current study, we describe development and validation of an indirect MERS‐CoV S ELISA to be used as part of our serological determination for evidence of previous exposure to the virus.

Keywords: antibodies, coronaviruses, immunity, MERS‐CoV, serology, surveillance

1. INTRODUCTION

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV) is a newly emerged virus that causes severe respiratory disease. As of August 2017, there have been 2066 laboratory confirmed cases with 720 fatalities (CFR 34.8%) reported to the World Health Organization.1 MERS cases have been identified from 27 countries in the Middle East, North Africa, Europe, the US, and Asia. New MERS cases continue to be detected. The CDC is continuing surveillance for MERS cases and outbreaks in the United States. Our current diagnostic algorithm for identification of MERS‐CoV‐specific serum antibodies in patients with a suspected history of MERS‐CoV infection includes initial screenings by indirect ELISA using MERS‐CoV nucleocapsid (N) protein, and then confirmation with immunofluorescent staining of MERS‐infected cells, and microneutralization titration (MNt) assays.2 Other international groups are primarily using a combination of indirect ELISA against the spike (S) protein with confirmatory neutralization assays.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 S1 ELISAS have been found to correlate well with neutralizing antibodies.9 As the spike (S) protein is the target of neutralizing antibodies, we are now including it in our diagnostic algorithm. In the current study, we report validation of an S indirect ELISA to be used in combination with N ELISA and MNt in identification of MERS‐CoV specific serum antibodies in patients with a history of MERS‐CoV infection.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Specimen collections

A collection of MERS‐CoV negative normal human sera (n = 400) were obtained throh a contract between the CDC and Emory University Transfusion Services. Ethics approval for the sample collection and use was approved by the CDC (Protocol Number: 1652) and Emory University (Protocol Number: 00045947) Institutional Review Boards. The donor identity was held only by Emory University Transfusion Services and was not released to the CDC in accordance with both institutions approved IRB protocols. The samples used in these studies were de‐identified and analyzed anonymously. Serum from a confirmed MERS‐CoV patient was used as a positive control for all of our assays. The positive control serum was collected from the first imported case of MERS‐CoV into the United States during the case investigation, with a neutralizing reciprocal endpoint titer of 320.10The panel of nine serum from patients with MERS‐CoV neutralizing antibodies were collected during a 2015 outbreak investigation and during a follow‐up investigation from a 2012 MERS‐CoV outbreak in Jordan.11 Specimens were prepared by the Jordan Central Public Health Laboratory (Amman, Jordan) and shipped to the CDC for testing. Personal identifiers are not held by the CDC and the CDC's IRB have deemed use of the sera as non‐human subjects research (research determination 2015 6446). Human serum with high titers to human coronaviruses 229E, HKU1, OC43, NL63 were collected during coronavirus investigations and were to examine assay cross reactivities. Personal identifiers are not head with these samples, and therefore CDC's IRB have deemed use of the sera as non‐human subjects research (research determination 2017_DVD_Thornburg_328). Laboratory confirmed SARS‐CoV patient serum was also included as negative control.

2.2. ELISA and Western blot analysis

Recombinant MERS‐CoV spike protein was purchased from (Sino Biological, Beijing, China) (catalog number 40069‐V08B). The manufacturer describes the protein as the ectodomain including amino acids 1‐1297 from the EMC/2012 strain produced by baculovirus. Immulon 2HB microtiter plates (Thermo Scientific, Rochester, NY) were coated with 100 μL 0.2 μg/mL S overnight at 4°C, washed three times with PBS‐T, and blocked with StabilCoat® (Surmodics, Eden Prairie, MN) at 37°C for 1 h. After blocking, plates were incubated with serum dilutions prepared in PBS‐T + 5% milk for 1 h at 37°C, washed three times with PBS‐T, incubated with HRP‐conjugated goat anti‐human IgG (H + L, KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) for X, washed again, and incubated with ABTS® peroxidase substrate (2, 2‐azino‐di‐(3‐ethylbenzthiazoline‐6‐sulfonate)) (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) at 37°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by adding ABTS® peroxidase stop solution (5% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate). The absorbance was measured at 405/490 nm using TECAN Infinity microplate reader (Mannedof, Switzerland). The absorbance (Optical Density) values of the negative control wells (n) coated with PBS were subtracted and divided from the OD values of antigen‐coated wells (p) and the average OD values of the antigen‐coated wells were calculated as (p‐n) and ratio (p/n). Recombinant MERS‐N was produced in BL21 cells as described previously.2 MERS‐N ELISAs were also performed as previously described.2

For Western blot analysis, 1 μg purified N, pET control lysate, or 0.5 μg purified S was run on an SDS page and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Sera, without MER‐CoV reactivity (NHS) and against SARS, 229E, OC43, HKU1, and MERS‐CoV, diluted at 1:400 were used to probe the blots with HRP goat anti human IgA, IgG, IgM (H and L). The blot was developed with DAB.

2.3. ROC analysis

Receiver‐operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to determine diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, and optimal test cut‐off OD values, of the assay using Excel and IBM SPSS Statistics 21 softwares.12, 13 Briefly, diagnostic sensitivity (%Se) and specificity (%Sp) of ELISA test results were calculated using microneutralization results as reference gold standard test for MERS‐CoV positive and negative samples. Optimal test cut‐off OD values were ascertained by plotting %sensitivity (%Se) and %specificity (%Sp) against ELISA cut‐off OD values as Two Graph—ROC plots and the intersection of the two curves was determined to be cut‐off OD for ELISA.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

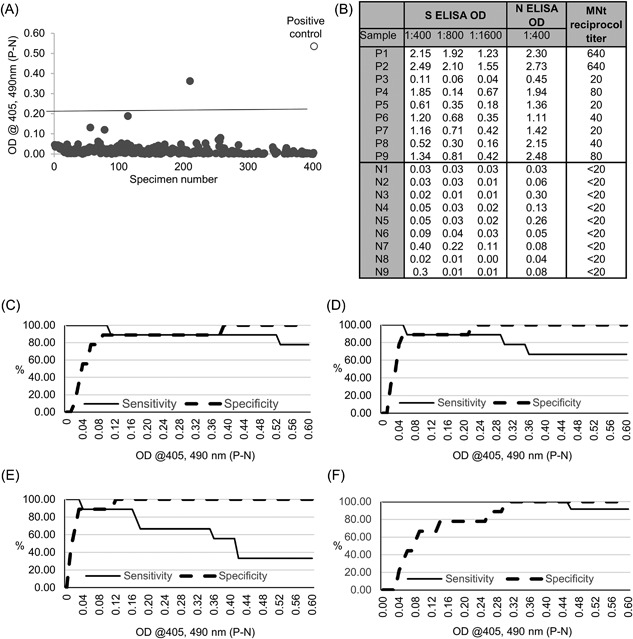

Using commercially prepared purified ectodomain MERS‐CoV S, we optimized coating and blocking conditions for an indirect ELISA using known MERS‐CoV negative and positive human sera (data not shown). After optimization, we tested sera from 400 normal human donors and one serum from an RT‐PCR confirmed MERS‐CoV patient for cross reactivities and MERS‐specific reactivity in an indirect ELISA at a dilution of 1:400. Of the 400 normal human sera, 396 had OD values less than 0.1 (Figure 1A). The remaining three normal sera had OD values of 0.12, 0.16, 0.19, and 0.36. The positive control serum had an OD value of 0.55 (Figure 1A). Using an OD cutoff of 0.2, one of the 400 normal human sera (0.25%) was above cutoff.

Figure 1.

A, MERS‐CoV S ELISA Optical densities (OD) of 400 normal human sera from participants without a history of MERS‐CoV infection, and one positive control serum from a patient with a history of MERS‐CoV infection. Sera were all diluted at 1:400. Each dot is one serum. The line is OD 0.2, the cutoff of the assay. B, Optical density (OD) at 1:400, 800, and 1600 used for MERS‐S ELISA, at 1:400 for the MERS‐N ELISA, and the reciprocal endpoint titer for the micorneutralization test (MNt) of each true positive (P1‐9) and true negative (N1‐9) sample. C‐E MERS‐S Two‐Graph ROC analysis of nine true positive and nine true negative sera at 1:400 C, 1:800 D, and 1:1600 E, to determine MERS‐CoV S ELISA cut‐off OD values and their association with diagnostic sensitivity (%Se) and specificity (%Sp). The sensitivity (%Se), or true positive, and specificity (%Sp), or true negatives are plotted as percentage (y axis) vs. cut‐off OD values (x axis). F, ERS‐N ELISA two‐graph ROC analysis of true positive and true negative at 1:400

In order to precisely test the specificity and sensitivity of the S ELISA, nine true negative sera with reciprocal endpoint microneutralization titers less than 20 and nine true positive sera with reciprocal endpoint microneutralization titers ranging from 20 to 640, were tested at dilutions of 200, 400, 800, and 1600 (Figure 1B). ROC analysis was performed to calculate the diagnostic sensitivity (true positive) and specificity (true negative) of the assay. At a standard screening dilution of 1:400, the sensitivity of the S ELISA remained at 89% or greater at ODs <0.51 (Figure 1C). Specificity increased to 89% at an OD of 0.09 and 100% at 0.39 (Figure 1C). At serum dilutions of 1:800 and 1:1600, the S ELISA remains highly specific, but loses sensitivity at higher ODs as can be expected (Figures 1D and 1E). For the sake of comparison, ROC analysis of MERS‐CoV N ELISA is shown for true positive and true negative sera at the screening dilution of 1:400 (Figure 1F). While sensitivity of the N ELISA is high across a wide range of ODs, the specificity only increases above 80% at an OD of 0.26.

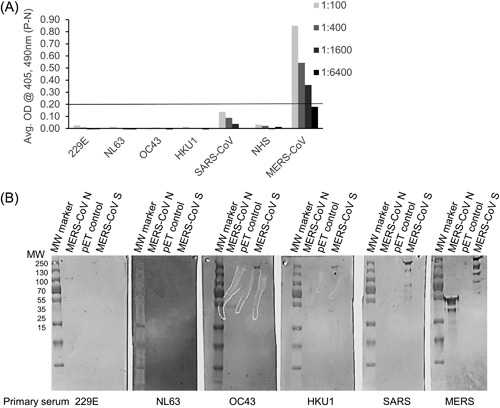

Cross reactivity of sera from patients with known histories of other human coronavirus infections were tested in the S ELISA and by Western blot analysis (Figure 2). Plates were coated with recombinant MERS‐CoV S, the human sera were diluted at 1:100, 1:400, 1:1600, and 1:6400, and used in an ELISA. Little to no cross reactivities against MERS‐CoV S were detected in pooled sera from patients with histories of 229E, NL63, OC43, or HKU1 human coronavirus infections, or pooled normal human serum (NHS) even at dilutions of 1:100 (Figure 2A). We observed some cross reactivity with human anti‐SARS‐CoV serum at dilutions of 1:100 and 1:400, though the ODs were below our cutoff value of 0.2 (Figure 2A). A serum from a MERS‐positive control serum had a final reciprocal endpoint titer of 1:1600 consistent with high neutralizing antibody titers detected by microneutralization assay (Figure 2A). All sera from humans with a history of other coronavirus infections and normal human sera had reciprocal endpoint titers of less than 100, with 400 and above considered positive.

Figure 2.

A, Sera from patients with known histories of human coronavirus infections 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, and SARS‐CoV, negative control normal human sera (NHS), and MERS‐CoV sera were diluted at 1:100, 1:400, 1:1600, and 1:6400 and used in S ELISA. The line represents the assay OD cutoff of 0.2. B, Western blot analysis of sera from patients with known histories of coronavirus infections (indicated at the bottom of the blots) against purified recombinant MERS‐CoV N, pET lysate negative control, and recombinant MERS‐CoV S

The same set of sera was also tested in Western blot analysis. Purified recombinant MERS‐CoV N protein (50 kDa), negative control lysate (pET control), and purified ectodomain of MERS‐CoV S protein (157 kDa) were run on SDS‐PAGE gels and transferred to membranes. Sera from patients with OC43 and HKU1 faintly detected MERS‐CoV N protein (Figure 2B). Sera from patients with 229E, OC43, and HKU1 also faintly detected MERS‐CoV S protein. More cross reactivity was seen between SARS serum and MERS‐CoV S protein (Figure 2B). Serum from the MERS‐CoV patient strongly detected both MERS‐CoV N and S as expected. These results suggest that while there is some weak cross reactivities between both MERS‐CoV N and S proteins and sera from patients who had a history of other coronavirus infections, the S cross reactivities are not strong enough to result in a positive signal by ELISA. While there have been studies suggesting there may be some cross reactivity between SARS patients sera and MERS‐CoV, our study is limited by the availability of only one patient serum.14

In this study, we have validated an S ELISA using recombinant baculovirus‐produced MERS‐CoV S ectodomain. We are opting to retain both N and S ELISAs during our MERS‐CoV serological screening process. We believe that MERS‐CoV N and S ELISAS are complementary for several reasons. First, as demonstrated by ROC analysis of S and N, at lower ODs, the S ELISA is more specific, while the N ELISA retains higher sensitivity across a large range of ODs. These data are not consistent with one publication examining serial blood draws from a single MERS‐CoV patient has suggested their S ELISA is more sensitive than an N ELISA.15 We have observed significant patient‐to‐patient differences in the quality and quantity of polyclonal antibody responses, and these conflicting data may be simply explained by human variation in immune response.

Recent work examining a panel of MERS‐CoV patient serum has suggested that S ELISA sensitivity can be increased by lowering the breakpoint in MERS‐CoV S ELISAs.16 While doing this would capture a larger percentage of patients who seroconvert, we have seen several patients who never develop detectable MERS‐CoV S antibodies, but do develop N antibodies (data not shown).

A second reason to retain both N and S ELISAS is there is evidence that antibodies against other coronavirus N proteins are detected earlier during infection than S proteins. Specifically, SARS‐CoV infection studies have indicated that antibodies against the N protein appear before antibodies against the S protein.17, 18 We frequently receive serum from patients who are acutely ill with suspected MERS‐CoV infections as part of surveillance in the United States and need to detect MERS‐CoV as early as possible during infection.

Third, while N ELISA may be more sensitive, examination of N and S cross reactivities suggest that antibodies directed against N, but not S, may cross react with within‐group coronaviruses,19 therefore using both N and S ELISAS may capture both sensitivity and specificity information.

As part of our screening process, we aim to capture as many potential positive serum as possible, and then perform confirmatory assays. In summary, during our new testing algorithm, both N and S ELISAS will be used as screening assays with sera diluted to 1:400. For all sera with ODs above assay cutoff, they will be diluted serially, fourfold from 1:100‐1:6400 and used for endpoint titer determinations. Sera that are positive for either N or S or both N and S (titers at 1:400, 1:1600, or 1:6400), will be tested via microneutralization with live MERS‐CoV along with 10% of negative sera. We will define positive MERS‐CoV serology as positive in two of three assays tested, N ELISA, S ELISA, and microneutralization or positive by microneutralization alone with microneutralization activity as confirmed positive.

4. DISCLAIMER

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

Trivedi S, Miao C, Al‐Abdallat MM, et al. Inclusion of MERS‐spike protein ELISA in algorithm to determine serologic evidence of MERS‐CoV infection. J Med Virol. 2018;90: 367–371. 10.1002/jmv.24948

REFERENCES

- 1.Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV). 2017, 2017.

- 2. Al‐Abdallat MM, Payne DC, Alqasrawi S, et al. Hospital‐associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin Infect Dis. 2014; 59:1225–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan JF, Sridhar S, Yip CC, Lau SK, Woo PC. The role of laboratory diagnostics in emerging viral infections: the example of the Middle East respiratory syndrome epidemic. J Microbiol. 2017; 55:172–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hemida MG, Perera RA, Al Jassim RA, et al. Seroepidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus in Saudi Arabia (1993) and Australia (2014) and characterisation of assay specificity. Euro Surveill. 2014; 19:pii 20828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meyer B, Drosten C, Muller MA. Serological assays for emerging coronaviruses: challenges and pitfalls. Virus Res. 2014; 194:175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muth D, Corman VM, Meyer B, et al. Infectious middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus excretion and serotype variability based on live virus isolates from patients in Saudi Arabia. J Clin Microbiol. 2015; 53:2951–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park WB, Perera RA, Choe PG, et al. Kinetics of serologic responses to MERS Coronavirus infection in humans, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015; 21:2186–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muller MA, Meyer B, Corman VM, et al. Presence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus antibodies in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide, cross‐sectional, serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015; 15:629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Park SW, Perera RA, Choe PG, et al. Comparison of serological assays in human Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)‐coronavirus infection. Euro Surveill. 2015; 20:pii 30042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kapoor M, Pringle K, Kumar A, et al. Clinical and laboratory findings of the first imported case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus to the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2014; 59:1511–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Payne DC, Iblan I, Rha B, et al. Persistence of antibodies against middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016; 22:1824–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greiner M. Two‐graph receiver operating characteristic (TG‐ROC): a Microsoft‐EXCEL template for the selection of cut‐off values in diagnostic tests. J Immunol Methods. 1995; 185:145–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Greiner M, Sohr D, Gobel P. A modified ROC analysis for the selection of cut‐off values and the definition of intermediate results of serodiagnostic tests. J Immunol Methods. 1995; 185:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan KH, Chan JF, Tse H, et al. Cross‐reactive antibodies in convalescent SARS patients' sera against the emerging novel human coronavirus EMC (2012) by both immunofluorescent and neutralizing antibody tests. J Infect. 2013; 67:130–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang W, Wang H, Deng Y, et al. Characterization of anti‐MERS‐CoV antibodies against various recombinant structural antigens of MERS‐CoV in an imported case in China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016; 5:e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ko JH, Muller MA, Seok H, et al. Suggested new breakpoints of anti‐MERS‐CoV antibody ELISA titers: performance analysis of serologic tests. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tan YJ, Goh PY, Fielding BC, et al. Profiles of antibody responses against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus recombinant proteins and their potential use as diagnostic markers. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004; 11:362–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Woo PC, Lau SK, Wong BH, et al. Differential sensitivities of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus spike polypeptide enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein ELISA for serodiagnosis of SARS coronavirus pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 2005; 43:3054–3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agnihothram S, Gopal R, Yount BL, Jr. , et al. Evaluation of serologic and antigenic relationships between middle eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus and other coronaviruses to develop vaccine platforms for the rapid response to emerging coronaviruses. J Infect Dis. 2014; 209:995–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]