Abstract

Purpose/Background

Bilateral squats are commonly used in lower body strength training programs, while unilateral squats are mainly used as additional or rehabilitative exercises. Little has been reported regarding the kinetics, kinematics and muscle activation in unilateral squats in comparison to bilateral squats. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare muscle activity, kinetics, and barbell kinematics between unilateral and bilateral squats with the same external load per leg in experienced resistance-trained participants.

Methods

Fourteen resistance-trained males (age 23 ± 4years, body mass 80.5 ± 8.5kg and height 1.81 ± 0.06m) participated. Barbell kinematics and surface electromyography (EMG) activity of eleven muscles were measured during the descending and ascending phase of each repetition of the squat exercises.

Results

Total lifting time was longer and average and peak velocity were lower for the bilateral squat (p<0.001). Furthermore, higher muscle activity was found in the three quadriceps muscles, biceps femoris (ascending phase) and the erector spinae (ascending phase) in the bilateral squat, while greater activation for the semitendinosis (descending phase) (p=0.003) was observed for the unilateral squat with foot forwards. In the ascending phase, the prime movers showed increased muscle activity with repetition from repetition 1 to 4 (p≤0.034).

Conclusions

Unilateral squats with the same external load per leg produced greater peak vertical ground reaction forces than bilateral squats, as well as higher barbell velocity, which is associated with strength development and rate of force development, respectively. The authors suggest using unilateral rather than bilateral squats for people with low back pain and those enrolled in rehabilitation programs after ACL ruptures, as unilateral squats are performed with small loads (28 vs. 135 kg) but achieve similar magnitude of muscle activity in the hamstring, calf, hip and abdominal muscles and create less load on the spine.

Level of Evidence

1b

Keywords: Ascending phase, descending phase, electromyography, kinematics, single limb squat, two-legged squat

INTRODUCTION

Bilateral exercises, such as snatches, deadlifts and two-legged back squats are frequently implemented as an important part of resistance training programs to improve strength, hypertrophy and power for the lower body.1-3 In recent years, the use of unilateral exercises such as lunges, step-ups and one-legged squats have become popular in strength and conditioning practice.4 However, these unilateral exercises, are regularly included within strength programs as additional exercises to the two-legged back squat to increase volume load or variation.4 Still, little is known regarding the effects of performing these unilateral exercises on muscle recruitment compared with unilateral exercises.

The ability to generate more force in sum performing two unilateral exercises (i.e. one-legged squat) than in a bilateral exercise (i.e. two-legged squat), is referred to as bilateral deficit.5-7 Consequently, including unilateral instead of bilateral exercises in training may be favorable to increase power and strength of the muscles, but the evidence is not conclusive.6,8,9 Furthermore, running, kicking, changing running direction, and jumping are all unilateral movement patterns that are performed in a unilateral weight-bearing phase. Therefore, to improve these performances most effectively, resistance training should closely resemble the mechanics and forces required to perform these necessary skills.10-12

Yet, few studies exist that have compared force output and muscle activity between bilateral and unilateral squats.12-16 In addition, these studies comparing bilateral with unilateral squats have used different protocols for both conditions (split legs and rear foot elevated) and different loads between bilateral and unilateral squats, and neither of these studies compared unilateral squats without any support on the rear leg with bilateral squats. During modified squats (i.e. rear foot on a box) force is produced by the front and rear leg, which is helped by the increase in the base of support.17,18 Thus, in fact they are not truly unilateral squats. Limited studies have performed analysis of single-leg squats, and these studies were focused on unilateral squats without extra load for rehabilitation purposes.19-22 To the authors’ knowledge, no studies have compared heavy weight (>80% of 1 repetition maximum) bilateral squats with unilateral, single-leg squats (with foot forwards or backwards) when the same external load per leg is used. Unilateral squats can be performed with the non-weight bearing foot positioned either forwards or backwards, which could influence weight distribution and thereby muscle activation and kinematics. These facets of single-leg squatting have not been studied before, to the authors knowledge. This information could help researchers, trainers and physiotherapists to gain insight into what happens when performing squatting exercises and thereby could help in designing rehabilitation or strength programs.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare muscle activity, kinetics, and barbell kinematics between unilateral and bilateral squats with the same external load per leg in experienced resistance-trained participants. A secondary purpose was to analyze muscle activity between unilateral squats with the lifted foot forwards vs. backwards. It was hypothesized that force output per leg would be the same between bilateral and unilateral back squats due to the same external load per leg being used. However, greater muscle activity of the leg muscles in the unilateral lifts was expected, which would be affected by an increase balance requirement during single-leg lifts.23 Furthermore, greater gluteus and erector spinae activation during the unilateral lifts with the foot backwards than with the foot forwards was hypothesized due to more flexion of the trunk.

MATERIALS & METHODS

A within-subjects, repeated measures design was used in which each subject performed all three squatting exercises: bilateral, unilateral with foot forwards and unilateral with foot backwards. A four-repetition maximum (4-RM) in bilateral squats was used because it is a typical training load used to increase maximal strength.24,25 The dependent variables were peak vertical force, velocity of the barbell, lifting time, and surface EMG activity of 11 muscles of the lower extremity and trunk during the descending and ascending phase of all four repetitions in each condition.

Subjects

Fourteen resistance-trained males (age 23 ± 4 years, body mass 80.5 ± 8.5 kg, height 1.81 ± 0.06 m) recruited from sport science education of the university volunteered to participate in this study. Each participant had at least two years of resistance training experience. The participants did not perform any resistance training exercises targeting the lower extremities in the 72 hours before the testing session. Participants without any history of neurological or orthopaedic dysfunction, surgery or pain in the spine and lower extremities, were recruited. All participants signed written informed consent forms containing risk factors and their right to withdraw from the research at any time without stating a reason. The study was approved by the local committee for medical research ethics and complied following the current ethical standards in sports and exercise research.26

Procedures

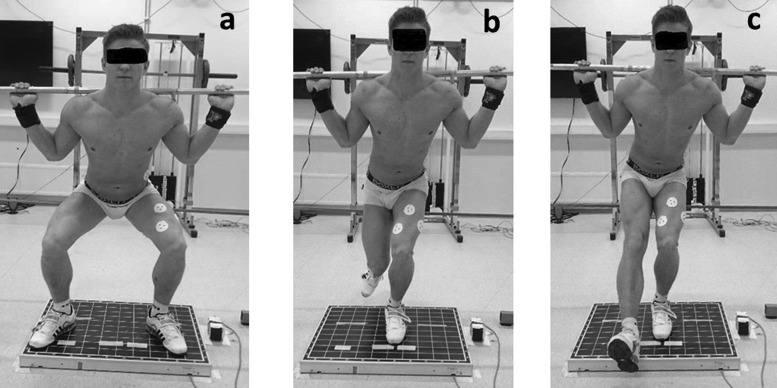

All participants performed three squats variations: a) bilateral back squat, b) unilateral squat with the non-weightbearing limb forwards, and c) unilateral squat with the non-weightbearing limb backwards (Figure 1). The 4-RM external load in the bilateral back squat was used to equalize the volume load between the squat variations. The equalized volume load that was used in the unilateral squats was calculated by:

Figure 1.

Squat positions. a) Bilateral, b) unilateral with foot backwards, and c) unilateral with foot forwards.

This is the load per leg in bilateral squats. The load in unilateral squats was then calculated by:

This is the external load that has to be lifted during unilateral squats.

Thus, when a participant of 80 kg lifting 4-RM of 160 kg in the bilateral squat, the participant had to lift a barbell of 40 kg ((240 kg / 2) – 80 kg) during the unilateral squats. The 4-RM for bilateral squat was 134.8 ± 25.7 kg and for the unilateral squat was 27.9 ± 11.4 kg. This resulted in a total lifted load of 215 ± 30.3 kg and 108 ± 15.1 kg in respectively the bilateral and unilateral squats.

Familiarization sessions

Before the test session, participants were given a two-week familiarization period (two to three training sessions) to establish and train with loads that approached their assumed 4-RM for bilateral squat (descent to 90 ° knee angle). Furthermore, participants practiced the unilateral squat techniques during these sessions, since they were less familiar with these two techniques with these loads. To reduce the technique and balance requirement while performing 4RM loads, a 90 ° knee angle during all lifts was used to ensure that the heel was in contact with the floor at all times. The squat variations were performed on the force plate and during the bilateral squat the participants placed their feet in their preferred position (to avoid extra stress upon the participant and increase the external validity towards training). The position of the feet was measured to maintain the foot position during the exercise (Figure 1a). From this position, the participant placed a barbell on the upper part of the shoulders (consistent with the position of a back squat) and flexed the knees down to a 90 ° knee angle. This position was found using a protractor. A horizontal rubber band was used to identify this lower position during the tests,27,28 which the participants had to touch with their proximal part of hamstring before starting the ascending movement. The participants were instructed to perform the ascending movement at maximal velocity during every repetition in each of the three squat conditions.

Warm up procedure

Prior to data collection, participants performed a five-minute jog as a general warm up followed by a specific warm-up protocol consisting of a) 10 repetitions of bilateral squats without extra load, b) 10 repetitions with the barbell (20kg) c) 10 repetitions with 50% of 1-RM d) 6 repetitions with 70% RM. The percentage of RM was estimated based on the self-reported 1-RM of the participants.

Data collection

After the warm up sets the assumed 4-RM (based on their previous experience) in bilateral squats was performed. Participants always started with the bilateral squat to ensure that they performed their actual 4-RM in bilateral squats. The load was increased or decreased by 2.5 kg or 5 kg until the actual 4-RM was obtained (1–3 attempts). Between each attempt and between each squat exercise, participants were given five minutes rest between each attempt to provide for an optimal performance.29 The order of the two unilateral squat variations was randomized and counter balanced to avoid an effect of fatigue. In the unilateral squats, participants started standing with the preferred foot on the force platform. The knee of the preferred foot was fully extended and the opposite knee bent approximately 90 degrees (foot backwards, Figure 1b) or fully extended but slightly elevated (foot forwards, Figure 1c) with a barbell on the shoulders on the back. From this position, the participant flexed the knee controlled and squatted down to a 90 ° knee angle. When the participants touched the rubber band with their proximal part of hamstring, they could start the ascending movement.

Measurements

To assess vertical ground reaction forces (1000 Hz) (kinetics) during each squat, a force plate (Ergotest Technology AS, Porsgrunn, Norway) was used. Average vertical ground reaction force per leg were calculated from the ascending phase together and peak vertical ground reaction force per leg for the descending and ascending phase. A linear encoder (ET-Enc-02, Ergotest Technology AS, Porsgrunn, Norway) connected to the barbell measured the vertical position and velocity (barbell kinematics) during all the squat exercises with a 0.075-mm resolution and counted the pulses with 10 millisecond intervals.30 Velocity of the barbell was calculated by using a 5-point differential filter with software Musclelab V10.4 (Ergotest technology AS, Porsgrunn, Norway).

Musclelab (Musclelab 6000 system, Ergotest AS Porsgrunn, Norway) was used to measure electromyographic (EMG) activity from eleven muscles: a) vastus medialis, b) vastus lateralis, c) rectus femoris, d) lateral side of gastrocnemius, e) gluteus maximus, f) gluteus medius, g) external abdominal oblique, h) erector spinae at L4-L5, i) semitendinosis, j) the long head of the biceps femoris, k) soleus, according to the recommendations of SENIAM,31 as in other studies.28,32 Before positioning the electrodes over each muscle, the skin was prepared by shaving, abrading, and cleaning with isopropyl alcohol to reduce skin impendence. To strengthen the signal, conductive gel was applied to self-adhesive electrodes (Dri-Stick Silver circular sEMG Electrodes AE-131, NeuroDyne Medical, Cambridge, MA, USA). The electrodes (11 mm contact diameter, 20 mm center-to-center distance) were placed on the participant´s stance side used in the unilateral squats. To minimize noise induced from external sources, the EMG raw signal was amplified and filtered using a preamplifier located as near to the pickup point as possible. The common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR) was 106 dB and the input impedance between each electrode pair was > 1012 Ω. The EMG signals were sampled at a rate of 1000 Hz. Signals were band pass (fourth-order Butterworth filter) filtered with a cut off frequency of 20 Hz and 500 Hz, rectified, integrated and converted to root-mean-square (RMS) signals using a hardware circuit network (frequency response 450 kHz, averaging constant 12 ms, total error ± 0.5%)25. To locate possible differences in muscle activity during the squat exercises, the average RMS was calculated for the descending and ascending phases for each four repetitions. The phases were identified with the linear encoder, which was synchronized with the EMG recordings using a Musclelab 6000 system and analyzed using software V10.4 (Ergotest Technology AS).

Statistical analyses

To assess the differences in kinetics, barbell kinematics and muscle activity between the three squat exercises, a repeated 2 (phase: descending, ascending) x 3 (exercise: bilateral squat, unilateral squat with foot forwards, unilateral squat with foot backwards) x 4 (repetition) analysis of variance (three-way ANOVA) design was used with Holm-Bonferroni post-hoc tests to identify the differences in barbell kinematics and EMG activity of the 11 muscles. If the sphericity assumption was violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser adjustments of the p-values were reported. All results are presented as mean ± SEM. The level for significance was set at p < 0.05. Effect size was evaluated with η2 (Eta partial squared) where 0.01<η2<0.06 constitutes a small effect, a medium effect when 0.06<η2<0.14 and a large effect when η2>0.14.33 Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago IL, USA).

RESULTS

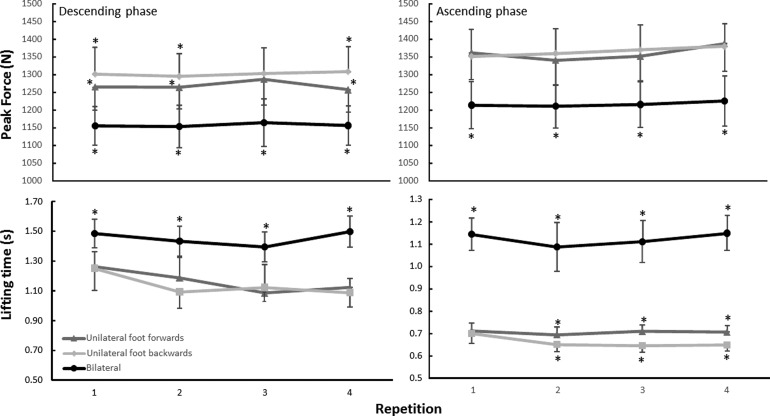

There was no significant difference in average force per leg (p=0.14) between the bi- and unilateral lifts. However, the peak vertical ground reaction forces per leg, and peak vertical ground reaction force was significantly greater in both unilateral squats compared with the bilateral squat and the peak vertical ground reaction force during the descending phase of the unilateral squat with the foot backwards was significantly greater than with the foot forwards (F=47.6, p<0.001, η2=0.86). Furthermore, a significantly greater peak vertical ground reaction force per leg during the ascending phase was observed compared with the descending phase in all lifts (F=15.63, p=0.004, η2=0.66, Figure 2). No significant effect of the peak vertical ground reaction force between repetitions was found among squats (F=1.4, p=0.257, η2=0.11, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean (SEM) peak vertical ground reaction force and lifting time for each repetition in the descending and ascending phases of the three squats.

* indicates a significant difference with the other exercises in this repetition on a p<0.05 level.

† indicates a significant difference between the descending and ascending phase on a p<0.05 level.

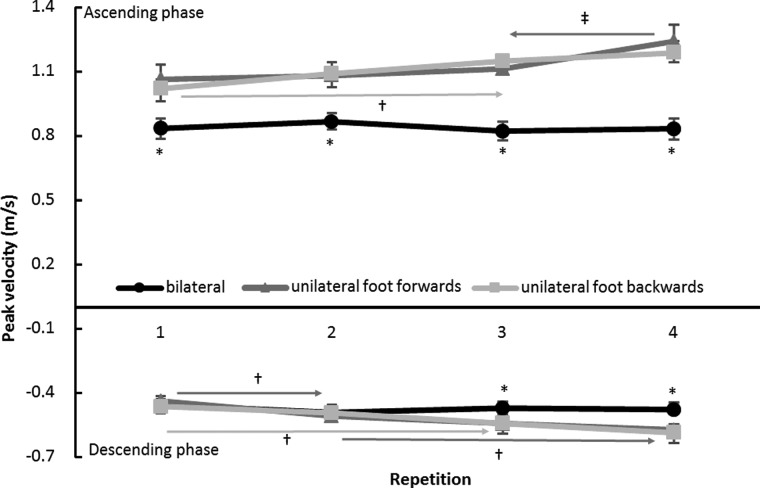

The lifting time differed significantly among the three exercises in both the descending (F=23.2, p<0.001, η2=0.74) and ascending phase (F=95.6, p<0.001, η2=0.89) with no significant effect for repetition (F≤1.6, P≥0.207, η2≥0.17). Furthermore, the peak velocity was significantly different among the three exercises during both the descending (F=3.8, p=0.045, η2=0.32) and ascending phases (F=20.5, p<0.001, η2=0.63) as well as for the factor repetition (F≥8.8, p<0.001, η2≥0.42, Figure 3). Furthermore, a significant interaction was found in the ascending phase (F=3.8, p=0.003, η2=0.24). Post hoc comparisons revealed that in both phases, the lifting times were longer during the bilateral lifts compared with the unilateral lifts (17% in descending and 39% in ascending phase) and that in the ascending phase, the lifting phase during repetition two to four the lifting time was significantly shorter (8%) during the unilateral lifts with the foot backwards compare to the lifts with the foot forwards (p=0.002, Figures 2 and 3). Peak velocity was 31% higher in the unilateral squats in the ascending phase (p<0.001) and 17% lower in the last two repetitions in the descending phase (p≤0.014) than the bilateral squats (Figure 3). Furthermore, peak velocity increased (faster down and upwards) in the unilateral squats from repetition one to two and repetition two to four with the foot backwards and from repetition one to three and repetition one to four with the foot forwards. In the ascending phase the peak velocity increased from repetition one to three (p≤0.018) for the unilateral squats with the foot backwards and peak velocity in repetition four was significantly higher than all other repetitions for the unilateral squats with the foot forwards (p≤0.012, Figure 3). No significant differences in peak velocity per repetition was found in the bilateral squats (p≥0.49).

Figure 3.

Mean (SEM) velocity of barbell for each repetition in the descending and ascending phases of the three squats.

* indicates a significant difference with the other exercises on a P<0.05 level.

† indicates a significant difference between this repetition and all right from the sign on a p<0.05 level.

‡ indicates a significant difference between this repetition and all left from the sign on a p<0.05 level.

Mean RMS EMG activity between the three exercises was significantly different for all three quadriceps muscles, biceps femoris and the erector spinae (F≥6.7, p≤0.026, η2≥0.46), but not for both gluteal muscles, soleus, gastrocnemius, and semitendinosis muscles (F≤0.98, p≥0.398, η2≤0.11). A comparison of the ascending phase to the descending phase revealed significantly greater EMG activity in all muscles except for the gastrocnemius and oblique external muscles (F≥6.5, p≤0.034, η2≥0.47, Table 1). An effect of repetition was found for the three quadriceps muscles, both gluteus muscles, semitendinosis, biceps femoris and erector spinae (F≥3.6, p≤0.028, η2≥0.31, Table 1). In addition, an interaction between lifting phase-repetition for all quadriceps muscles and erector spinae (F≥3.7, p≤0.039, η2≥0.32), an interaction between exercise-phase for the rectus femoris, erector spinae and semitendinosis (F≥3.7, p≤0.047, η2≥0.32) and an interaction between exercise-phase-repetition for the semitendinosis (F=2.35, p=0.045, η2=0.23) were found. Post hoc comparison revealed that muscle activation during the bilateral squats was significantly greater for the rectus femoris (22%, p≤0.003), erector spinae (47%, p≤0.018) in the descending phase, medial vastus in all the repetitions in the descending phase (18%, p≤0.011) and the lateral vastus in the descending phase and the ascending phase in the first three repetitions (17%, p=0.017) compared with the unilateral squats. Furthermore, significantly greater EMG activity of the semitendinosis with unilateral squats with the foot forwards in the descending phase (30%, p<0.01) was found compared with the other two exercises, while during the descending phase of the unilateral squat with the foot backwards EMG activity of the biceps femoris was significantly lower (26%, p≤0.011) than the other two exercises (Table 1). Post hoc comparison also revealed that EMG activity increased in the ascending phase from repetition one with mostly repetition three and four for most exercises for all quadriceps muscles, gluteus medius, and the biceps femoris (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean RMS (SEM) EMG activity of the eleven muscles for each repetition in the descending and ascending phase of the three squats. All results are presented in μV as means + /- SD.

| Descending phase | Significant between repetitions | Ascending phase | Significant between repetitions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle (μV) | Repetition | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Rectus Femoris | Bilateral | 212 ± 29* | 210 ± 34* | 216 ± 28* | 216 ± 29* | 208 ± 28* | 223 ± 34* | 227 ± 32 | 247 ± 39* | ||||

| Unilat. F.F. | 128 ± 18 | 138 ± 24 | 149 ± 26 | 142 ± 24* | † | 161 ± 21 | 174 ± 24 | 204 ± 35 | 206 ± 29 | 1 with 4 | |||

| Unilat. F.B. | 157 ± 24 | 152 ± 24 | 154 ± 25 | 162 ± 26* | 166 ± 26 | 179 ± 25 | 202 ± 33 | 208 ± 31 | 1 with 3, 4 | ||||

| Vastus medialis | Bilateral | 207 ± 36* | 224 ± 35* | 232 ± 34* | 210 ± 33* | † | 268 ± 35# | 294 ± 36 | 309 ± 40 | 310 ± 39 | 1 with 2, 3 | ||

| Unilat. F.F. | 169 ± 32 | 172 ± 29 | 191 ± 34 | 173 ± 28 | † | 244 ± 36 | 282 ± 49 | 292 ± 44 | 299 ± 47 | 1 with 3, 4 | |||

| Unilat. F.B. | 162 ± 30 | 166 ± 33 | 161 ± 30 | 178 ± 36 | 4 with 1-3 | † | 231 ± 35# | 254 ± 41 | 257 ± 47 | 279 ± 44 | 1 with 4 | ||

| Vastus Lateralis | Bilateral | 247 ± 20* | 273 ± 27* | 285 ± 37# | 284 ± 34# | † | 292 ± 29* | 332 ± 37* | 336 ± 35* | 332 ± 32 | 1 with 2-4 | ||

| Unilat. F.F. | 226 ± 25 | 227 ± 24 | 243 ± 31 | 236 ± 24 | † | 258 ± 25 | 273 ± 29 | 300 ± 32 | 317 ± 36 | 2 with 3, 4 | |||

| Unilat. F.B. | 217 ± 25 | 220 ± 22 | 217 ± 21# | 230 ± 28# | † | 253 ± 26 | 274 ± 27 | 274 ± 28 | 305 ± 33 | 1 with 4 | |||

| Gluteus Medius | Bilateral | 72 ± 6 | 84 ± 6 | 82 ± 6 | 88 ± 8 | † | 133 ± 13 | 143 ± 14 | 143 ± 13 | 153 ± 17 | 1 with 4 | ||

| Unilat. F.F. | 80 ± 8 | 90 ± 11 | 89 ± 10 | 88 ± 9 | † | 155 ± 17 | 157 ± 19 | 160 ± 20 | 171 ± 18 | 1 with 4 | |||

| Unilat. F.B. | 70 ± 9 | 75 ± 7 | 76 ± 7 | 75 ± 6 | † | 141 ± 13 | 166 ± 20 | 163 ± 16 | 164 ± 16 | 1 with 3, 4 | |||

| Gluteus Maximus | Bilateral | 55 ± 7 | 79 ± 12 | 79 ± 12 | 85 ± 15 | † | 143 ± 24 | 157 ± 32 | 151 ± 27 | 176 ± 35 | |||

| Unilat. F.F. | 75 ± 10 | 77 ± 11 | 90 ± 15 | 91 ± 15 | † | 164 ± 22 | 151 ± 25 | 166 ± 29 | 166 ± 27 | ||||

| Unilat. F.B. | 55 ± 6 | 66 ± 8 | 66 ± 9 | 71 ± 11 | † | 135 ± 21 | 152 ± 25 | 167 ± 25 | 168 ± 27 | ||||

| Erector Spinae | Bilateral | 127 ± 23* | 122 ± 22* | 126 ± 23* | 131 ± 24* | 131 ± 26 | 138 ± 27 | 133 ± 27 | 144 ± 28 | ||||

| Unilat. F.F. | 54 ± 10 | 54 ± 10 | 46 ± 7* | 57 ± 12 | † | 96 ± 20 | 91 ± 16 | 97 ± 21 | 113 ± 24 | 3 with 4 | |||

| Unilat. F.B. | 68 ± 7 | 82 ± 13 | 77 ± 13* | 82 ± 12 | † | 93 ± 19 | 107 ± 19 | 104 ± 23 | 117 ± 20 | ||||

| Oblique External | Bilateral | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | ||||

| Unilat. F.F. | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | |||||

| Unilat. F.B. | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 1 with 2-4 | ||||

| Semitendinosis | Bilateral | 45 ± 7 | 53 ± 9 | 50 ± 8 | 53 ± 9 | † | 85 ± 14 | 84 ± 15 | 98 ± 15 | 88 ± 13 | |||

| Unilat. F.F. | 61 ± 8* | 66 ± 8* | 73 ± 9* | 72 ± 10* | 1 with 3, 4 | † | 73 ± 10 | 85 ± 13 | 83 ± 12 | 90 ± 14 | |||

| Unilat. F.B. | 43 ± 8 | 45 ± 7 | 43 ± 6 | 45 ± 6 | † | 72 ± 12 | 88 ± 14 | 89 ± 14 | 91 ± 17 | ||||

| Biceps Femoris | Bilateral | 57 ± 8 | 61 ± 8 | 66 ± 9 | 65 ± 9# | † | 111 ± 15* | 105 ± 17 | 121 ± 23 | 120 ± 20 | |||

| Unilat. F.F. | 56 ± 9 | 65 ± 12 | 66 ± 10 | 72 ± 14 | 1 with 2-4 | † | 86 ± 14 | 93 ± 16 | 107 ± 21 | 113 ± 19 | 1 with 3, 4 | ||

| Unilat. F.B. | 43 ± 7* | 52 ± 7* | 53 ± 8* | 54 ± 8# | 1 with 2-4 | † | 87 ± 15 | 97 ± 15 | 104 ± 16 | 112 ± 20 | 1 with 3, 4 | ||

| Soleus | Bilateral | 60 ± 6 | 69 ± 8 | 68 ± 8 | 68 ± 8 | † | 103 ± 15 | 104 ± 12 | 101 ± 14 | 108 ± 14 | |||

| Unilat. F.F. | 72 ± 12 | 77 ± 14 | 74 ± 11 | 67 ± 9 | † | 105 ± 20 | 99 ± 18 | 90 ± 15 | 95 ± 15 | ||||

| Unilat. F.B. | 74 ± 13 | 72 ± 13 | 73 ± 11 | 72 ± 8 | † | 113 ± 24 | 103 ± 18 | 109 ± 19 | 106 ± 24 | ||||

| Gastrocnemius | Bilateral | 57 ± 18 | 57 ± 11 | 50 ± 8 | 56 ± 12 | 71 ± 12 | 63 ± 10 | 70 ± 11 | 67 ± 11 | ||||

| Unilat. F.F. | 61 ± 18 | 60 ± 14 | 62 ± 13 | 58 ± 10 | 77 ± 18 | 66 ± 11 | 60 ± 8 | 67 ± 9 | |||||

| Unilat. F.B. | 54 ± 18 | 53 ± 12 | 51 ± 11 | 53 ± 9 | 69 ± 13 | 62 ± 11 | 74 ± 15 | 66 ± 11 | |||||

F.F = non-weightbearing foot held forward, F. B = non-weightbearing foot held backward

indicates a significant difference with the other exercises for this repetition on a p<0.05 level.

indicates a significant difference between the descending and ascending phase on a p<0.05 level.

indicates a significant difference between these two exercises on this repetition on a p<0.05 level.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to compare muscle activity, kinetics and barbell kinematics between unilateral with the lifted foot forwards vs. backwards and bilateral squats with the same external load per leg in experienced, resistance-trained participants. The main findings were a lower peak barbell velocity and a longer lifting time for the bilateral squat compared to the unilateral squats. Greater activation of the rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, biceps femoris and erector spinae occurred during the bilateral squat compared to the unilateral squats. In addition, for the unilateral squat with foot forward, a greater muscle activation was found for the semitendinosis and vastus medialis and a lower activation of the erector spinae in comparison to the unilateral squat foot backwards.

In the bilateral and unilateral squats, the same external load per leg was used, determined by equations (see methods). In the unilateral squats, the participants could produce greater peak vertical ground reaction forces than during the bilateral squats (Figure 2). This resulted in a higher peak velocity and shorter lifting time in the descending and ascending phase during these lifts (Figures 2 and 3). These differences in velocity are likely due to the fact that the unilateral squats were performed at a lower percentage of 1-RM than the 4-RM load in the bilateral squats.34 Furthermore, it was shown that the peak velocities during the unilateral squats increased in both phases during the set of repetitions (Figure 3), while no difference in peak velocity was found during the set of repetitions of the bilateral squats. Probably due to the small base of support, the participants were more cautious about their movement velocity to avoid an imbalance especially while performing the first repetition in unilateral squats. After the first repetition, which is more about familiarization, they increased their movement velocity. Similar development has been reported in previous studies on squatting in which after the first repetition, the peak velocity increases.28,32

It was expected that muscle activity of the leg muscles would be greater in the unilateral lifts than in the bilateral back squats.23 Yet, the EMG activity of the rectus femoris, vastus medialis and vastus lateralis was greater in the bilateral squat compared to the unilateral squats except for vastus medialis in the unilateral squat foot forwards (ascending phase, Table 1). The reason for these unexpected findings (not supporting the initial hypothesis) was probably body positioning over the feet during the lifts. During bilateral squats, feet can be positioned wider than during unilateral squats. Even when the depth was the same with the same knee angle, hip and ankle joint angles could be different to maintain balance. Thereby, more force can be delivered by the quadriceps during bilateral squats. This is also visible in lesser EMG activity of the vastus medialis during the ascending phase in the unilateral squats with the foot backwards. The speculation is supported by previous studies15,35 examining the effects of greater stability requirement (i.e. reduced base of support or unstable surfaces). Performing unilateral instead of bilateral squats represent a greater stability requirement to maintain equilibrium and position and could explain the findings. In comparison, McCurdy, et al.16 also found greater quadriceps activity in bilateral squats compared with modified single-leg squats. They also reported greater hamstring and gluteus activity during the modified single-leg squats, which contrasts with the findings presented here.

As indicated before, even with the same external load per leg, unilateral squats were probably performed at a lower percentage of 1-RM than the 4-RM load in the bilateral squats as shown by greater vertical ground reaction forces and velocities during unilateral as compared to bilateral squats. Using a lower percentage of 1-RM this would result in a lower activation of the quadriceps, thereby explaining the difference in muscle activation between bilateral and unilateral squats.

Performing the unilateral squat with the foot forwards resulted in greater muscle activation of the semitendinosis in the descending phase compared to the two other squat variations. However, performing the unilateral squat with foot backwards resulted in lower biceps femoris activation. Placing the foot forwards, the center of mass would shift forward. The participant probably had to reposition the weight by less hip external rotation and more knee abduction at the deepest knee angle than in the other two lifts.20 The speculation was supported by Khuu, et al.20 who showed that unloaded unilateral squats caused a greater internal knee adductor moment during the lifts with the foot forwards than unilateral squats with the foot backwards. To control these knee adductor moment and joint angles during the descending movement, the semitendinosis and vastus medialis in the unilateral squat with the foot forwards have to be more active. Hence, this type of unilateral squats could target the semitendinosis and vastus medialis more than the other lifts which is of importance for avoiding ACL injuries.36,37

The lower muscle activity of the biceps femoris during the unilateral squat with the foot backwards was surprising. With the foot backwards, the trunk would likely compensate by leaning forwards20 which would cause an increase in hamstrings activity as Kulas et al.22 found. Furthermore, DeForest et al.14 found increased biceps femoris activity during unilateral squats with the rear leg elevated compared with bilateral squats. However, this discrepancy can be explained by the difference in loads used in the present study and in DeForest et al.14 The external weight DeForest et al.14 used in the unilateral squats in was half of the weight of the bilateral squats. However, they did not account for the body weight that had to be lifted which resulted in a heavier load lifted during the unilateral squats compared to the bilateral squats. Nevertheless, a lower biceps femoris activity during lifts is not necessarily negative. If a person targets the biceps femoris and quadriceps (lateral vastus) muscles too much, this could increase the chance for ACL ruptures.36,37

Similar activity in the gluteus maximus and medius among the three lifts was surprising. It was expected that the unilateral squats would result in an increased internal hip abduction moment which would cause a greater gluteus activity as McCurdy et al.16 found. Still, McCurdy et al.16 used a heavier intensity (3-RM) than the present study in both bilateral and unilateral squats which would cause a greater demand on these gluteal muscles in the unilateral squats. However, in the present study the total average load per leg was controlled between the bilateral and the unilateral squats and therefore this could have resulted in the same gluteal activity. Furthermore, McCurdy et al.16 used a modified unilateral squat with an elevated box to rest the other foot. That procedure likely increased the base of support and decreased the stability requirement which may have resulted in a greater force generating condition and thereby possible activation of the gluteus. Previous studies have demonstrated decreased prime mover activations if the muscle or muscle groups have both to stabilize and maximize force production compared to more stable exercises.15,35 Finally, McCurdy et al.16 used females in contrast to present study.

The erector spinae activity during the descending phase was significantly greater in the bilateral squats compared with the unilateral squats. The results were not surprising since the external weight on the spine was much greater during these lifts compared with the unilateral squats (134.8 ± 25.7 vs. 27.9 ± 11.4). These results have clinical importance, as participants with lower back pain can train by performing unilateral squats that induce similar levels of muscle activity in the hamstring, calf, hip, and abdominal muscles, with reduced load on the spine. Furthermore, with these relatively smaller loads, greater activation of semitendinosis and lower activation of quadriceps muscles was found which is an advantage against possible chances of ACL strains.36,37 In addition, since the weight used in the unilateral squats was probably lower than the 4-RM load for the unilateral squats it would be easy to increase the weights to the intensity (3-RM) used in the studies of McCurdy and colleagues13,16,38 to enhance gluteal muscle activation.

There are some limitations in the study. Firstly, no 2D or 3D kinematic analysis of the lower extremities or trunk was performed due the limitations of the equipment that could examine these outcomes. An analysis of the angles during various lifts would give more accurate answers for the difference in the muscle activation and kinematic parameters. Secondly, the adaptation period of learning the unilateral squats with weights could be longer to avoid a possible learning effect during testing as indicated by the increasing peak velocity during the sets. A longer adaptation period would probably result in a higher peak velocity at the first repetition during the unilateral squats. Thirdly, the participants were resistance trained and 90 ° knee flexion depth was used. The results may therefore not be generalized to other populations and squat depths.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the current study indicate that unilateral squats with the same external load per leg produces significantly greater peak vertical ground reaction forces than bilateral squats as well as significantly higher barbell velocity. However, there is significantly greater activation of the rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, biceps femoris and erector spinae during a bilateral squat in comparison to a unilateral squat. Furthermore, performing unilateral squats with the foot forward results in significantly greater activation of the semitendinosis and reduced activation of the other quadriceps muscles. The authors suggest using unilateral rather than bilateral squats for people with low back pain and those enrolled in rehabilitation programs after ACL ruptures may be beneficial, as unilateral squats are performed with small loads (28 vs. 135 kg) but achieve similar levels of muscle activity in the hamstring, calf, hip and abdominal muscles and create less load on the spine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stone MH Potteiger JA Pierce KC, et al. Comparison of the effects of three different weight-training programs on the one repetition maximum squat. J Strength Cond Res. 2000;14(3):332-337. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Usui S Maeo S Tayashiki K, et al. Low-load slow movement squat training increases muscle size and strength but not power. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37(4):305-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen K Cronin J. Training loads for the development of lower body muscular power during squatting movements. Strength Cond J. 2009;31(3):17-33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speirs DE Bennett MA Finn CV, et al. Unilateral vs. bilateral squat training for strength, sprints, and agility in academy rugby players. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(2):386-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nijem RM Galpin AJ. Unilateral versus bilateral exercise and the role of the bilateral force deficit. Strength Cond J. 2014;36(5):113-118. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rejc E Lazzer S Antonutto G, et al. Bilateral deficit and EMG activity during explosive lower limb contractions against different overloads. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(1):157-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oda S Moritani T. Maximal isometric force and neural activity during bilateral and unilateral elbow flexion in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1994;69(3):240-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebben WP Feldmann CR Dayne A, et al. Muscle activation during lower body resistance training. Int J Sports Med. 2009;30(1):1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behm DG Power KE Drinkwater EJ. Muscle activation is enhanced with multi- and uni-articular bilateral versus unilateral contractions. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 2003;28(1):38-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young WB. Transfer of strength and power training to sports performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perf. 2006;1(2):74-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sale D MacDougall D. Specificity in strength training: a review for the coach and athlete. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1981;6(2):87-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones MT Ambegaonkar JP Nindl BC, et al. Effects of unilateral and bilateral lower-body heavy resistance exercise on muscle activity and testosterone responses. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(4):1094-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCurdy K Kutz M O'Kelley E, et al. External oblique activity during the unilateral and bilateral free weight squat. Clin Kinesiol. 2010:16-21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeForest BA Cantrell GS Schilling B. Muscle activity in single- vs. double-leg squats. Int J Exerc Sci. 2014;7(4):302-310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen V Fimland MS Brennset Ø, et al. Muscle activation and strength in squat and bulgarian squat on stable and unstable surface. Int J Sports Med. 2014;35(14):1196-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCurdy K O'Kelley E Kutz M, et al. Comparison of lower extremity EMG between the 2-Leg squat and modified single-Leg squat in female athletes. J Sport Rehabil. 2010;19(1):57-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saeterbakken A Andersen V Brudeseth A, et al. The effect of performing bi- and unilateral row exercises on core muscle activation. Int J Sports Med. 2015;36(11):900-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saeterbakken AH Fimland MS. Muscle force output and electromyographic activity in squats with various unstable surfaces. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(1):130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escamilla RF Zheng N MacCleod TD, et al. Patellofemoral joint force and stress during the wall squat and one-leg squat. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(4):879-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khuu A Foch E Lewis CL. Not all single leg squats are equal: a biomechanical comparison of three variations. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11(2):201-211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards J Thewlis D Selfe J, et al. A biomechanical investigation of a single-limb squat: implications for lower extremity rehabilitation exercise. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):477-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulas AS Hortobágyi T DeVita P. Trunk position modulates anterior cruciate ligament forces and strains during a single-leg squat. Clin Biomech. 2012;27(1):16-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cresswell AG Ovendal AH. Muscle activation and torque development during maximal unilateral and bilateral isokinetic knee extensions. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2002;42(1):19-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ACSM. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Tillaar R Saeterbakken A. Effect of fatigue upon performance and electromyographic activity in 6-RM bench press. J Hum Kin. 2014;40:57-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harriss DJ Atkinson G. Ethical standards in sport and exercise science research: 2016 update. Int J Sports Med. 2015;36(14):1121-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saeterbakken AH Andersen V van den Tillaar R. Comparison of kinematics and muscle activation in free-weight back squat with and without elastic bands. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(4):945-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van den Tillaar R Andersen V Saeterbakken AH. The existence of a sticking region in free weight squats. J Hum Kin. 2014;42:63-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahimi R. Effect of different rest intervals on the exercise volume completed during squat bouts. J Sports Sci Med. 2005;4(4):361-366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnason A Sigurdsson SB Gudmundsson A, et al. Risk factors for injuries in football. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(1):6-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermens HJ Freriks B Disselhorst-Klug C, et al. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J Electrom Kinesiol. 2000;10(5):361-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Tillaar R. Kinematics and muscle activation around the sticking region in free weight barbell back squat. . Kinesiol Slov. 2015;21(1):15-25. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez-Medina L Gonzalez-Badillo JJ. Movement velocity as a measure of loading intensity in resistance training. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31:347-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saeterbakken AH Fimland MS. Electromyographic activity and 6RM strength in bench press on stable and unstable surfaces. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(4):1101-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zebis MK Andersen LL Bencke J, et al. Identification of athletes at future risk of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures by neuromuscular screening. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):1967-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zebis MK Skotte J Andersen CH, et al. Kettlebell swing targets semitendinosus and supine leg curl targets biceps femoris: an EMG study with rehabilitation implications. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(18):1192-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCurdy K Langford GA Cline AL, et al. The reliability of 1- and 3 RM tests of unilateral strength in trained and untrained men and women. J Sports Sci Med. 2004;3(3):190-196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]