Abstract

Bone fracture in egg laying hens is a growing welfare and economic concern in the industry. Although environmental conditions and management (especially nutrition) can exacerbate it, the primary cause of bone weakness and the resulting fractures is believed to have a genetic basis. To test this hypothesis, we performed a genome-wide association study to identify the loci associated with bone strength in laying hens. Genotype and phenotype data were obtained from 752 laying hens belonging to the same pure line population. These hens were genotyped for 580,961 SNPs, with 232,021 SNPs remaining after quality control. Each of the SNPs were tested for association with tibial breaking strength using the family-based score test for association. A total of 52 SNPs across chromosomes 1, 3, 8, and 16 were significantly associated with tibial breaking strength with the genome-wide significance threshold set as a corrected P value of 10e−5. Based on the local linkage disequilibrium around the significant SNPs, 5 distinct and novel QTLs were identified on chromosomes 1 (2 QTLs), 3 (1 QTL), 8 (1 QTL) and 16 (1 QTL). The strongest association was detected within the QTL region on chromosome 8, with the most significant SNP having a corrected P value of 4e−7. A number of candidate genes were identified within the QTL regions, including the BRD2 gene that is required for normal bone physiology. Bone-related pathways involving some of the genes were also identified including chloride channel activity, which regulates bone reabsorption, and intermediate filament organization, which plays a role in the regulation of bone mass. Our result supports previous studies that suggest that bone strength is highly regulated by genetics. It is therefore possible to reduce bone fractures in laying hens through genetic selection and ultimately improve hen welfare.

Keywords: bone strength, genetic selection, genome-wide association, laying hens, welfare

INTRODUCTION

Bone weakness and the consequent fractures represent a considerable welfare and economic problem in the layer industry. It is a pathological condition caused by a progressive loss in the amount of mineralized structural bone during the laying period. It was estimated that 30% of commercial egg laying hens experience at least one incidence of bone fracture during their laying period, prior to depopulation and processing (Gregory and Wilkins, 1989). Bone fractures are considered a welfare problem because of the acute and chronic pains associated with broken bones and the skeletal deformities that often remain from improperly healed fractures (Nasr et al., 2012). Economically, bone fractures affect production and income of farmers through its effect on mortality and egg production (Weber et al., 2003). In the pure lines that contribute to the commercial hybrid layers, selection pressure has been on higher egg production with lower BW and feed intake. Bishop et al. (2000) reported that about 40% of the variation in the bone strength phenotype was explained by genetic differences between the hens. Two lines selected for low and high bone index clearly differed in bone strength characteristic after just 5 generation of divergent selection, with significant reduction in the incidence of bone fracture and keel bone deformities in the line selected for high bone index (Bishop et al., 2000; Fleming et al., 2004). A more recent study of these lines showed that there were fewer keel bone fractures and a higher bone mineral density in the line selected for high bone strength (Stratmann et al., 2016). A linkage study for bone strength in an F2 cross between the high and low bone index lines showed that quantitative trait loci (QTL) explaining variation in bone quality were segregating in the original breeding population (Dunn et al., 2007). The objective of the present study was to perform a genome-wide association study (GWAS) for bone strength in a grandparent population of laying hens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Care and Use Information

All animals in this study were part of the regular breeding program at Lohmann Tierzucht GmbH. The sampling for this experiment was performed after the routine culling of all the birds at the end of lay.

Genetic Stock and Housing

Birds used for the study were a pedigree population of Lohmann LSL white hens at the end of their life. The birds were hatched over 3 wk and assigned to 3 different houses according to hatch week. All birds were fed the same diet, formulated to meet the birds’ requirements and according to management protocols. The critical components were as follows: metabolizable energy 11.4 MJ/kg, crude protein 17.0%; crude fat 6.7%, crude fiber 3.9%, calcium 3.9%, and available phosphorus 0.35%. Individual egg records and BW at postmortem were available for each hen. After the routine slaughter of birds at the end of lay, tibial bones were dissected for breaking strength testing.

Methodology for Measuring Breaking Strength

The phenotype in the study was tibial breaking strength. The breaking strength was determined by a 3-point destructive bending test, using a JJ Lloyd LRX50 materials testing machine running the software package Nexygen 2.0 (http://www.chatillon.com) and fitted with a 2,500 N load cell. The bending jig consists of two 10-mm-diameter steel bar supports, 30 mm apart at center, and a 10-mm-diameter cross head, which approaches at 30 mm/min. Breaking strength was determined as the maximum load achieved before failure, and the failure point was set at a load which was 30% of the maximum. Stiffness was calculated from the load/displacement curve and was a measure of the bone’s resistance to bending. For more details about this procedure, see Jepsen et al. (2015).

Phenotypic Analysis

Two thousand birds were initially phenotyped for tibial breaking strength using the procedure described above. The tibial bone on the right leg of the birds was sampled after slaughter. Birds that had laid less than 200 eggs in the production cycle and those that had laid less than 9 eggs in the 3 wk prior to measurement were removed from the analysis, with approximately 1,600 birds left. The residuals for tibial strength were then calculated by fitting BW in a linear regression model, and birds that had high leverages (outliers) were removed. Subsequently, the remaining birds were sorted based on the residuals and the top and bottom 480 were selected for the study. It was verified that there was no significant difference in BW between the birds in the top 480 and the birds in the bottom 480 (P > 0.10). A summary of phenotypic information on the birds used in this study is presented in Table 1 classified by hatch week, which clearly shows that the birds differ in their tibial breaking strength, but not BW or egg production.

Table 1.

Phenotypic values for BW, tibial breaking strength, and total egg number

| Week of hatch | Top or tail | BW (g) | SD | Tibial breaking strength (N) | SD | Total egg number | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Tail | 1,525.0 | 153.1 | 167.3 | 25.2 | 235.4 | 10.5 |

| Top | 1,564.0 | 135.8 | 254.2 | 26.1 | 234.7 | 9.7 | |

| 25 | Tail | 1,624.0 | 155.9 | 155.8 | 23.3 | 232.9 | 11.4 |

| Top | 1,607.0 | 137.4 | 238.7 | 28.4 | 231.1 | 9.3 | |

| 26 | Tail | 1,725.0 | 162.1 | 173.5 | 25.1 | 236.8 | 10.9 |

| Top | 1,717.0 | 149.1 | 260.6 | 31.5 | 236.1 | 12.0 | |

| P value | Top/tail | 0.601 | <0.001 | 0.120 | |||

| P value | Hatch week | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

SD is the corresponding standard deviations for the 480 top and 480 tail hens used for this study. The top and tail were defined using the residual produced after fitting BW in a linear regression. Significance values for an analysis of variance on the 2 variables of top/tail and hatch week are presented to indicate that BW and egg production do not differ between the 2 extremes of the distribution, but there is a difference in tibial breaking strength. The variable hatch week had an effect on all traits.

Genotyping and Quality Control

The assay used for genotyping was the 600 k Affymetrix Axiom HD genotyping array (Kranis et al., 2013) using the GeneTitan system, which had 580,961 SNPs across chromosomes 1 through 28 and was applied to 960 individuals. Thirty-four thousand eight hundred and forty-one SNPs were removed due to unknown chromosome. The genotype data were then subjected to a series of quality control checks using the procedure implemented in the GenABEL R package (Aulchenko et al., 2007): SNPs with low minor allele frequency (MAF; <1%), SNPs with low call rates (<90%), SNPs with extreme deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P value = 1e−12), birds with low call rates (<95%), and birds with too high autosomal heterozygosity (≥0.4) were removed. In total, 232,021 markers and 752 birds passed all criteria and were used for the subsequent GWAS. For the GWAS analysis, the genotypes were coded as 0, 1, or 2. In this case, birds that were homozygous for the reference allele of an SNP were coded as 0, the heterozygous birds were coded as 1, and birds that were homozygote for the nonreference allele of an SNP were coded as 2.

Statistical Analyses

An initial analysis was carried out using a multiple regression to determine the possible factors that could be confounded with SNP effects on tibial breaking strength. Body weight (P value = 2e−16), total egg production (P value = 0.00228), and week of hatch (P value = 8.44e−06) had effects that significantly differed from zero on tibial breaking strength. These factors were taken into account in all subsequent analyses.

Because the individuals in this study were from the same pure line population with a high degree of genetic relatedness, there will be a confounding effect of the, unknown, pedigree, which can inflate the test statistics if a standard score test for association is used. Instead, the so-called mixed polygenic model approach was adopted. Specifically, the family-based score test for association (FASTA) as put forward by Chen and Abecasis (2007) and implemented in the GenABEL R package (Aulchenko et al., 2007) was used. The FASTA approach consists of 2 steps: First, a mixed polygenic model is run, which takes into account the genetic relationship between individuals in the study (in this case, the genomic kinship matrix):

| (1) |

where µ is the intercept (mean trait value), G is the contribution of polygenes to the trait value, and e the residuals. This model yields the maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs) for the variance explained by polygenes () the error variance () fitted mean value and the heritability (h2). The model can also be modified to include possible covariates such as BW, egg production, and so on, and the model then becomes:

| (2) |

where Ci is a vector with the ith covariate, and βi is the coefficient of regression of the trait onto the covariate. SNP effects were also estimated at this stage by fitting each SNP at a time as a covariate in the model. However, to determine whether or not a particular SNP has a significant effect on the trait, the MLEs for the variance components (not SNP effects) from Eq. 2 were combined in a FASTA test statistics (Chen and Abecasis, 2007) as follows:

| (3) |

where g is a vector containing individual genotype for a particular SNP (in this case the SNP being tested, E[g] is a vector containing identical elements that equals 2F where F is the frequency of the A allele at the locus/SNP being tested and ϕ is the genomic kinship matrix. Y is a vector with phenotypic records, and µ is the overall population mean. From the FASTA equation, it is not immediately clear where the SNP effects are accommodated. This is because, unlike other tests such as the Wald or likelihood ratio test, the FASTA test (being a score test) does not require actual estimates of the information under the alternative hypothesis, which in this case are the solutions of SNP effects from the mixed polygenic model. In other words, with a score test, the model estimated does not include the parameters of interest. So instead of using likelihood estimates of SNP effects from the polygenic model, the FASTA approach tests for improvement of model fit if SNPs, which are currently omitted, are added to the model. The score test is also very suitable for GWAS because the test is very powerful when the actual value of a parameter is close to the value under the null hypothesis, which is the case for many of the SNPs.

The FASTA procedure results in unbiased estimates of SNP effects and correct P values (Chen and Abecasis, 2007). A genome-wide significance threshold was set as a corrected P value of 10e−5. FASTA test statistic follows a chi-square distribution with 1 df if the pedigree is complete and 100% correct. Because this is usually not the case, genomic control (Yang et al., 2011) was further applied to correct for possible inflations of the residuals, hence the choice of corrected P values as against the standard P values.

Defining QTL Regions

Quantitative trait loci were defined surrounding each of the significant SNPs identified based on the local linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure. For each significant SNP, a pairwise LD determined by r2 was calculated between itself and all other SNPs within 5-Mb upstream of its position and 5-Mb downstream of its position using CGmisc (Kierczak et al., 2015), an R package that enables advanced analysis and visualization of GWAS data/results. With CGmisc (Kierczak et al., 2015), it was possible to graphically illustrate the LD between an index SNP and the SNPs in its vicinity. A cutoff for r2 was set at 0.6, and any SNP whose LD with the significant SNP equals or exceeds the threshold and which was furthest upstream of the significant SNP was set as the start of the QTL and the SNP furthest downstream was set as the end of the QTL. The LD threshold of 0.6 was set taking into account the high average LD observed in white layer populations (Abasht et al., 2009). QTLs whose positions in the genome overlapped even partially were combined into a single QTL region with the maximum and the minimum positions set as boundaries. Subsequently, these QTL regions were examined to identify the genes within their boundaries.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

The genes identified within QTL regions were subjected to a gene set enrichment analysis using DAVID version 6.8 (accessed 22 February 2017 at https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp). The genes were also analyzed individually for possible functions related to bone strength. To avoid the omission of genes that may play important roles in bone strength but are located outside the QTL regions, for example, genes affected by medium- to long-range enhancers, the genome-wide significance threshold was lowered to an arbitrary value of 0.0004. The original FASTA result was then rechecked to identify the SNPs that became significant given the new threshold. Using CGmisc (Kierczak et al., 2015) and the UCSC Genome Browser, the position of the significant SNPs was checked to see if they are located within any gene. Furthermore, a 2-Mb region was defined around each of the significant SNPs, 1-Mb upstream and 1-Mb downstream of the significant SNPs. Genes that were identified within these regions were included in the list for further gene set enrichment analysis. Special emphasis was placed on identifying the common pathways for the genes.

RESULTS

Phenotype

The tibial breaking strength phenotype (in newton) had minimum and maximum values of 108.6 and 367.6, respectively, and a mean value of 209.5. The SD was 50.5 with a coefficient of variation of 0.24. Two covariates were identified that had significant effect (α = 0.05) on tibia breaking strength. These were BW (P value = 2e−16, β = 0.11), which was positively correlated with bone strength, and total egg production (P value = 0.00228, β = −0.47), which indicates that birds with unusually low egg production had stronger bones. Week of hatch as a fixed factor also showed a significant effect on tibia breaking strength (P value = 8.44e−06), indicating that bone strength deteriorates as the laying period progresses.

Genome-Wide Associations

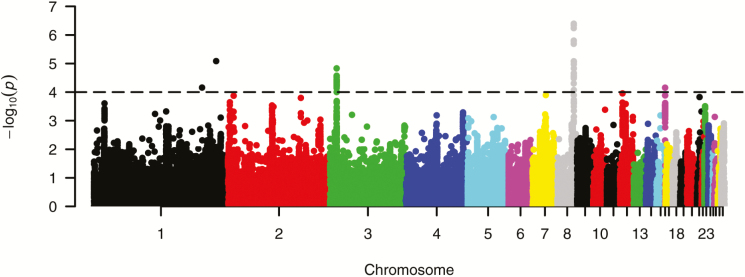

After quality control, a total of 232,021 SNPs and 752 individuals were retained and were used to estimate genome-wide associations. A breakdown of the number of SNPs per chromosome after quality control is presented in Table 2. In the first step of the FASTA analysis, MLEs were obtained for heritability and genetic variance. The trait (tibial breaking strength) showed a very high heritability of 0.55 and a genetic SD of 46.6 N. In the second step, SNP effects with their SE, 1 df chi-square test for association, standard P values and corrected P values (after genomic control) were estimated. From the result, a total of 52 SNPs reached the genome-wide threshold of 10e−5. These SNPs were spread across chromosome 1 (2 SNPs), chromosome 3 (29 SNPs), chromosome 8 (20 SNPs), and chromosome 16 (1 SNP) (Fig. 1). The top SNP identified in the study was subsequently fitted as a covariate in a polygenic model, and the heritability of the trait was re-estimated. The value obtained for heritability after this procedure was 0.53, which means that about 2% of the variation in tibial breaking strength phenotype is explained by allelic variation at this locus alone, although this might be inflated given the fact that we selected top and tails from the initial population of hens.

Table 2.

Number of SNPs per chromosome retained after quality control

| Chromosome | Number of SNPs | Chromosome | Number of SNPs | Chromosome | Number of SNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43,024 | 11 | 6,399 | 21 | 3,979 |

| 2 | 26,599 | 12 | 5,201 | 22 | 1,761 |

| 3 | 22,625 | 13 | 3,455 | 23 | 3,095 |

| 4 | 20,621 | 14 | 6,089 | 24 | 3,356 |

| 5 | 13,883 | 15 | 2,859 | 25 | 514 |

| 6 | 11,025 | 16 | 171 | 26 | 2,033 |

| 7 | 10,787 | 17 | 3,198 | 27 | 2,336 |

| 8 | 8,468 | 18 | 3,637 | 28 | 2,098 |

| 9 | 8,888 | 19 | 3,885 | ||

| 10 | 8,496 | 20 | 3,539 |

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of genome-wide associations for tibia breaking strength in laying hens. The −log10 of corrected P values is shown for each SNP (y-axis). The genome-wide threshold is indicated by a horizontal dashed line.

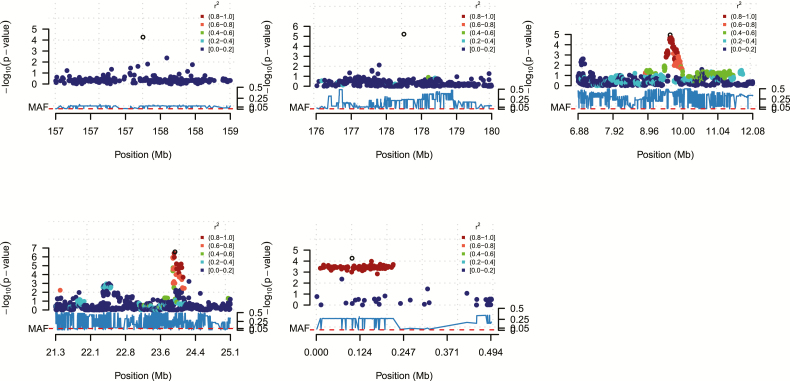

An LD analysis was carried out in the regions containing the significant SNPs, which was done to establish if the significant SNPs were in LD with each other and with other SNPs in the regions. On chromosome 1, the 2 significant SNPs were not in LD with each other, suggesting that there are 2 separate regions of interest on the chromosome. It is expected that they will not be in LD given that they are spaced far apart (>20-Mb distance). On a closer examination, it was found that not only were these SNPs far apart and not in LD with each other, they were also not in LD with any other SNP in their vicinity (Fig. 2A and B). Because they are singular SNPs and not in LD with other SNPs, their MAF were checked and it was found that they both had very low MAFs, which barely passed the cutoff criteria for MAF of 0.01 as implemented during quality control. Their MAFs were 0.02582 and 0.01962, respectively. This suggests these 2 SNP effects on chromosome 1 should be considered preliminary and further validation is required.

Figure 2.

LD plots showing the local LD structure around the most significant SNPs in the QTL regions on chromosome 1 (A: top-left and B: top-center), chromosome 3 (C: top-right), chromosome 8 (D: bottom left), and chromosome 16 (E: bottom-center). Each diamond represents an SNP marker. The y-axis indicates the significance of the SNP [−10log(P)], while the color coding indicates the level of LD with the top SNP (open diamond). The minor allele frequencies in the chromosome region are depicted under the x-axis.

Chromosome 3 had the highest number of significant SNPs with a total of 29 that passed the genome-wide significance threshold. The result showed that these SNPs were very close to each other and were all within a 1-Mb region. LD analysis also showed they were in high LD with each other and with other nonsignificant SNPs in the region (Fig. 2C).

The strongest association signal was observed within the significant region on chromosome 8. This region had a total of 20 SNPs that reached the genome-wide significance threshold, all of which were close to each other and were within a 1-Mb region (Fig. 2D). The most significant SNP in the region had a corrected P value of 4e−7. Chromosome 16 had the fewest number of markers compared with the other chromosomes (Table 2). This chromosome had only a single SNP that reached the genome-wide significance threshold, but the SNP was in high LD with other SNPs in its vicinity (Fig. 2E).

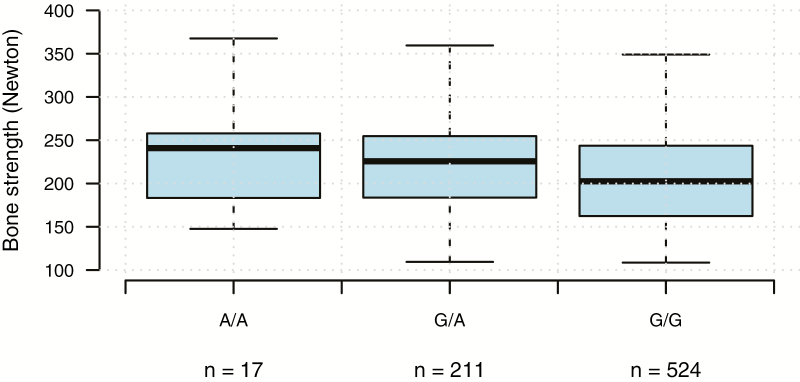

The effect of the most significant SNP (rs16644190, chromosome 8) on the phenotype was investigated to see if different allele combinations for this SNP results in observed differences in the phenotype (Fig. 3). The result clearly indicates that individuals with A/A at this locus have higher average bone strength than individuals with A/G or G/G at the same locus. The difference in average bone strength between A/A individuals and G/G individuals is approximately 40 N, although this difference could be inflated because we selected top and tails from the original 2,000 hens.

Figure 3.

Boxplot showing the effect of the most significant SNP (rs16644190, chromosome 8) on tibia breaking strength phenotype in newton.

QTL Regions

After defining the local LD range for each significant SNP on chromosome 3, all the LD ranges nicely overlapped into a single QTL region. The same was observed for the significant SNPs on chromosome 8, which also formed a single QTL region. The LD range around the significant SNP on chromosome 16 also represented a QTL region. Taking into account the 2 separate SNPs on chromosome 1, there were in total 5 distinct QTLs for bone strength that were identified in the study (Table 3).

Table 3.

QTLs found in the chicken genome associated with tibia breaking strength

| Chromosome | QTL start (bp) | QTL end (bp) | QTL length (bp) | Number of significant SNPs in QTL | Number of genes | Top SNP | Effect (SE) of top SNP (in newton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 178,054,319 | 178,054,319 | 1 | 1 | 0 | rs15522139 | 33.91 (7.49) |

| 1 | 157,504,202 | 157,504,202 | 1 | 1 | 0 | rs315807703 | 32.69 (8.10) |

| 3 | 8,878,928 | 9,976,543 | 1,097,616 | 29 | 23 | rs315928688 | 12.85 (2.92) |

| 8 | 21,420,506 | 24,110,421 | 2,689,916 | 20 | 51 | rs16644190 | 19.05 (3.70) |

| 16 | 11,466 | 217,707 | 206,242 | 1 | 28 | rs315192660 | −11.89 (2.95) |

Genes Within the QTL Regions

The positions of the 2 significant SNPs on chromosome 1 were checked in the UCSC Genome Browser (Karolchik et al., 2003) to see if they are located within any gene. The result showed that none of them are located within any gene. The QTL region on chromosome 3 was also examined for the presence of genes. The search turned up a number of known genes and some Ensembl predicted genes (Supplementary Table S1). Some of the genes located within this region code for proteins that are yet to be characterized, whereas some of the genes code for proteins that are involved in processes unrelated to bone strength. Some of the genes however have functions that are related to skeletal development. A number of known genes and Ensembl predicted genes were also annotated within the QTL region on chromosome 8 and also within the QTL region on chromosome 16 (Supplementary Table S1).

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

After the genome-wide significance threshold was lowered to 0.0004, a total of 121 SNPs across 9 chromosomes were identified as suggestive. A 2-Mb region was defined around each of these significant SNPs, and genes within these regions were identified. The genes are presented in Supplementary Table S2. Despite the high number of genes identified, only a few of the identified genes were seen to be involved together in the same process. DAVID reported 17 significant processes (GO terms) that involve some of the genes in Supplementary Table S2 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Gene set enrichment test involving the genes within 2 Mb of the SNP with P < 0.0004

| Process (GO term) | Number of genes in process | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-protein transferase activity | 11 | 0.002 |

| Intercalated disc | 4 | 0.011 |

| MHC class II protein complex | 3 | 0.013 |

| Negative regulation of axon extension involved in axon guidance | 4 | 0.019 |

| Mitophagy in response to mitochondrial depolarization | 7 | 0.019 |

| Palate development | 6 | 0.022 |

| Regulation of membrane potential | 5 | 0.023 |

| Chloride channel activity | 4 | 0.024 |

| Oxalate transmembrane transporter activity | 3 | 0.035 |

| Secondary active sulfate transmembrane transporter activity | 3 | 0.035 |

| Sulfate transmembrane transporter activity | 3 | 0.035 |

| Connexon complex | 3 | 0.035 |

| Intermediate filament organization | 3 | 0.042 |

| Keratinocyte differentiation | 4 | 0.043 |

| Endoplasmic reticulum membrane | 11 | 0.049 |

| Bicarbonate transmembrane transporter activity | 3 | 0.049 |

| Complement activation | 3 | 0.049 |

DISCUSSION

A number of factors have been put forward which are thought to affect the strength of bones in laying hens, one of which is mineral depletion in the bones. Because of its high demand for eggshell formation for example, calcium is often mobilized from structural bone especially when dietary supply is inadequate, thereby leaving the hens with weak bones characterized by osteoporosis (Riddell, 1992). The confinement of birds in limited spaces such as the battery cage housing system limits the ability of the hens to exercise. This limitation results in osteoporosis due to disuse and hence the consequent high incidences of fractures under such conditions. It has been shown that birds with ability to exercise in an aviary environment have stronger bones and lower cases of bone fracture than those confined in cages (Fleming et al., 2006). The way and manner in which hens are handled especially during depopulation and processing also affects the incidences of bone fractures. A study showed that about 16%–25% of hens suffer broken bones during the process in which they are removed from cages and about 30% of hens experience new fractures during loading and transportation to processing facilities (Gregory and Wilkins, 1989; Gregory et al., 1990, 1994). Although all the factors mentioned above can exacerbate bone weakness and fractures in laying flocks and there is no doubt the hen’s environment and its nutrition should be optimized, the factor that is thought to have the greatest contribution to the variation in the trait is believed to be genetics (Bishop et al., 2000; Fleming et al., 2006).

Given that bone strength was not accounted for in past selection programs, it is hypothesized that over several generations of genetic selection for traits such as high egg production, bone strength has been negatively affected resulting in birds with genetically weaker bones. If indeed this is the case, it is then possible to reverse the condition with genetic selection for bone strength. Even if the hypothesis that selection for increased egg production increased osteoporosis is not correct, and indeed, there is good evidence that similar problems of poor mineralization existed 80 yr ago (Warren, 1937) and that there was no difference in bone quality between layer lines with different selection histories (Hocking et al., 2009), the evidence that it could be improved by genetics is as valid as it was in 1937. In their selection experiment, Mandour et al. (1989) showed that after 3 generations of selection for humeral strength in broilers, the selected line had higher humeral strength than the control line.

In this study, we have shown that bone strength is indeed highly influenced by genetics in addition to environmental factors. The phenotype tibial breaking strength as a representation of bone strength was highly variable in the population we studied. Although the observations were censored, in that only the top and bottom individuals in terms of bone strength were selected, the difference between the observed minimum and maximum value is a clear indication of the amount of variation that exist for this trait. In the study of Bishop et al. (2000), they reported a heritability for tibial strength to be 0.45, lower than the heritability we found for tibial breaking strength in our study (0.55). The reason for this higher heritability may be because we used high-density markers and genomic kinship matrix in our estimation, which is able to capture more genetic variation than when using a classical best linear unbiased prediction with pedigree-based kinship matrix (Meuwissen, 2007). It may also be that the heritability is higher because the population on which we performed our estimation is a preselected population. Individuals were included in the study based on their phenotypic value and therefore the heritability of the trait in this case may not be a true representation of the heritability in an unselected population. In any case, it is clear that the heritability is higher than for most studied traits, which means that the trait can be improved upon through genetic selection in a relatively short period of time either using markers or traditional selection if the phenotype could be captured in a routine manner.

This study, unlike previous studies, utilized a substantially larger number of SNPs, which resulted in higher resolution and increased power/accuracy of detecting QTLs linked to bone strength. The genome-wide significance threshold of 10e−5 was comparable to other livestock GWAS studies, but not based on Bonferroni correction. We based our arbitrary genome-wide significance by looking at the commonly used P values for GWAS applied to livestock which is usually between 10e−4 and 10e−6. For an overview of different threshold levels for GWAS, see Hayes (2013).

The study identified a total of 52 SNPs that reached or exceeded the genome-wide threshold of 10e−5. These SNPs were spread across 5 QTL regions on chromosome 8 (20 SNPs), chromosome 3 (29 SNPs), chromosome 1 (2 SNPs), and chromosome 16 (1 SNP). Because the 2 significant SNPs on chromosome 1 were not in LD with each other and >20-Mb apart, they were considered to be separate QTLs. Dunn et al. (2007) found a significant QTL for osteoporosis on chromosome 1 using an F2 design with divergently selected hens from the same line used in this study. We did not find a significant QTL at this locus. The position of the QTL found in that study was 370cM on chromosome 1. This position corresponds to 108,473,589 bp, 65-Mb upstream of one of the QTL found in our study on chromosome 1 and 49-Mb upstream of the second (Table 2). It should be noted however that their annotation was based on the galGal3 chicken assembly, whereas our annotation was based on the galGal4 assembly. There was a relatively large QTL detected on chromosome 3 with a range from 8,878,928 to 9,976,543 bp. This QTL had a number of genes annotated within its boundaries (see Supplementary Table S2). A study by Melissa et al. (2005) also found some suggestive QTLs linked to bone traits on chromosome 3. The suggestive QTLs they found were however not significant after they adjusted for the variation in BW and egg production. In our study, the genes identified within the QTL on chromosome 3 perform several functions, but the ones that are related to bone strength are as follows:

Transmembrane Protein 17 (TMEM17)-Chr3: (9119138–9123843): This gene is required for ciliogenesis and sonic hedgehog/SHH signaling, with both processes playing critical roles in skeletal development in vertebrates (Goetz and Anderson, 2010; Nosavanh et al., 2015).

Actin-Related Protein 2 (ACTR2)-Chr3: (10012981–10031445): A very important biological process involving this gene is cilium assembly or ciliogenesis. Cilia as pointed out above play important roles in skeletal development (Goetz and Anderson, 2010).

Solute Carrier Family 1 (Glutamate/Neutral Amino Acid Transporter), Member 4 (SLC1A4)-Chr3: (9933016–9965656): This gene has been shown to have some implications for the proper functioning of skeletal muscles (Kanai and Hediger, 2003), and it is known that activity has a positive effect on bone strength.

WD Repeat Containing Planar Cell Polarity Effector (WDPCP)-Chr3: (9380005–9522526): This gene also plays a role in ciliogenesis (Viguet-Carrin et al., 2006).

The strongest association was detected within the QTL region on chromosome 8. It was surprising however that most of the genes identified within this region were participating in other functions unrelated to bone strength, mostly immunity functions that may reflect expression of genes from bone marrow as a source of cells that subsequently differentiate into macrophages and osteoclasts. Genes whose function are related to bone strength are as follows:

Podocan (PODN)-Chr8: (24625586–24658081): The human ortholog of this gene has been shown to be involved in collagen binding and development. Collagen plays an important role in bone strength (Viguet-Carrin et al., 2006) and was shown to differ in the laying hen selection lines (Sparke et al., 2002).

Single-Stranded DNA Binding Protein 3 (SSBP3)-Chr8: (25250764–25301485): This gene may be involved in transcription regulation of the alpha 2(I) collagen gene, thereby playing an indirect role in bone strength. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify a QTL on chromosome 8 related to bone traits in laying hens.

Another QTL was found on chromosome 16. There was only one gene within this region however whose function is related to bone strength. This was the Osteoclast inhibitory lectin (BRD2)-Chr16: (100331–109182), which is required for normal bone physiology (Kartsogiannis et al., 2008). In a human study, this gene was associated with a reduction of bone mineral density in women (Pineda et al., 2008). This is also a novel QTL, given that no other study has reported a QTL on chromosome 16 linked to bone traits in laying hens.

To identify the pathways in which potential candidate genes are involved, we lowered the genome-wide significance threshold to 0.0004. Given this new threshold, several other genes were identified (Supplementary Table S2) and the processes in which these genes are involved (Table 3). We conducted a literature search for these processes to identify those that have any function related to bone strength. Two of the processes in Table 3 that have bone-related functions are as follows:

Intermediate filament organization: a recent study showed that a deficiency of the intermediate filament results in a reduction of bone mass in vivo (Moorer et al., 2016). Chloride channel activity: inhibition of the chloride channel inhibits bone resorption. Bone resorption is the resorption of bone tissue, that is, the process by which bone tissues are broken down by osteoclasts, resulting in the release of minerals such as calcium from bone tissues into the blood (Teitelbaum, 2000). The release of calcium from bone tissue into the blood due to dietary deficiency, for example, is one of the causes of osteoporosis in laying hens (Riddell, 1992). Osteoclast numbers were shown to alter after divergent selection for bone strength in the laying hen line used in this study (Fleming et al., 2006).

Bone fracture in laying hens is a growing welfare and economic concern. Although this problem can partly be addressed through proper nutrition and housing management, genetic selection provides an alternative that can result in a gradual but more permanent solution. To genetically improve bone strength, however, it is important to get an insight into the genetic architecture underlying the trait. In this study, we identified loci linked to tibial breaking strength in laying hens. Fifty-two significant SNPs located in 5 distinct and novel QTL regions were found across chromosomes 1, 3, 8, and 16. These QTL regions had a number of promising candidate genes, some of which have been shown to participate in processes influencing bone strength in laying hens. Gene enrichment analysis revealed important processes, such as the chloride channel activity and intermediate filament organization, which are linked to bone strength and in which some of the identified genes play critical roles. The identified QTLs and the genes they encompass provide important information for genetic selection to improve bone strength and ultimately the welfare of layers.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Journal of Animal Science online.

Footnotes

The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council Formas and The Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, UK, through an ERANET grant “Better Bones” BB/M028291/1; the Roslin Institute was funded with a BBSRC Institute Strategic Programme Grant BB/J004316/1.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abasht B., Sandford E., Arango J., Settar P., Fulton J. W., O’Sullivan N. P., Hassen A., Habier D., Fernando R. L., Dekkers J. C., et al. 2009. Extent and consistency of linkage disequilibrium and identification of DNA markers for production and egg quality traits in commercial layer chicken populations. BMC Genomics 10(E. Suppl 2):S2. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-S2-S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulchenko Y. S., Ripke S., Isaacs A., and Van Duijn C. M.. 2007. GenABEL: An R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 23:1294–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S., Fleming R., McCormack H., Flock D., and Whitehead C.. 2000. Inheritance of bone characteristics affecting osteoporosis in laying hens. Br. Poult. Sci. 41:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.-M., and Abecasis G. R.. 2007. Family-based association tests for genomewide association scans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81:913–926. doi:10.1086/521580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn I., Fleming R., McCormack H., Morrice D., Burt D., Preisinger R., and Whitehead C.. 2007. A QTL for osteoporosis detected in an F2 population derived from White Leghorn chicken lines divergently selected for bone index. Anim. Genet. 38:45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R., McCormack H., McTeir L., and Whitehead C.. 2004. Incidence, pathology and prevention of keel bone deformities in the laying hen. Br. Poult. Sci., 45:320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R., McCormack H., McTeir L., and Whitehead C.. 2006. Relationships between genetic, environmental and nutritional factors influencing osteoporosis in laying hens. Br. Poult. Sci. 47:742–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz S. C., and Anderson K. V.. 2010. The primary cilium: A signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11:331–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory N., and Wilkins L.. 1989. Broken bones in domestic fowl: Handling and processing damage in end-of-lay battery hens. Br. Poult. Sci. 30:555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory N., Wilkins L., Eleperuma S., Ballantyne A., and Overfield N.. 1990. Broken bones in domestic fowls: Effect of husbandry system and stunning method in end-of-lay hens. Br. Poult. Sci. 31:59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory N., Wilkins L., Knowles T., Sørensen P., and Niekerk T. V.. 1994. Incidence of bone fractures in European layers. Proceedings of 9th European Poultry Conference; 1994. European Poultry Conference; p. 126–128.

- Hayes B. 2013. Overview of statistical methods for genome-wide association studies (GWAS). In: Gondro C., van der Werf J., and Hayes B., editors, Genome-wide association studies and genomic prediction. Methods in molecular biology (methods and protocols). Vol. 1019 Humana Press, Totowa, NJ; p. 149–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking P., Sandercock D., Wilson S., and Fleming R.. 2009. Quantifying genetic (co) variation and effects of genetic selection on tibial bone morphology and quality in 37 lines of broiler, layer and traditional chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 50:443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen K. J., Silva M. J., Vashishth D., Guo X. E., and van der Muelen M. C. H.. 2015. Establishing biomechanical mechanisms in mouse models: Practical guidelines for systematically evaluating phenotypic changes in the diaphyses of long bones. J. Bone Miner. Res. 30:951–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y., and Hediger M. A.. 2003. The glutamate and neutral amino acid transporter family: Physiological and pharmacological implications. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 479:237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karolchik D., Baertsch R., Diekhans M., Furey T. S., Hinrichs A., Lu Y., Roskin K. M., Schwartz M., Sugnet C. W., and Thomas D. J.. 2003. The UCSC Genome Browser Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:51–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartsogiannis V., Sims N. A., Quinn J. M., Ly C., Cipetić M., Poulton I. J., Walker E. C., Saleh H., McGregor N. E., and Wallace M. E.. 2008. Osteoclast inhibitory lectin, an immune cell product that is required for normal bone physiology in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 283:30850–30860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierczak M., Jabłońska J., Forsberg S. K., Bianchi M., Tengvall K., Pettersson M., Scholz V., Meadows J. R., Jern P., and Carlborg Ö.. 2015. Cgmisc: Enhanced genome-wide association analyses and visualisation. Bioinformatics 31:3830–3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranis A., Gheyas A. A., Boschiero C., Turner F., Yu L., Smith S., Talbot R., Pirani A., Brew F., Kaiser P., et al. 2013. Development of a high density 600 K SNP genotyping array for chicken. BMC Genomics 14:59. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandour M., Nestor K., Sacco R., Polley C., and Havenstein G.. 1989. Selection for increased humerus strength of cage-reared broilers. Poult. Sci. 68:1168–1173. [Google Scholar]

- Melissa A., Patricia Y., and Diane E.. 2005. Identification of quantitative trait loci associated with bone traits and body weight in an F2 resource population of chickens. Genet. Sel. Evol. 37:677–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen T. 2007. Genomic selection: Marker assisted selection on a genome wide scale. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 124:321–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorer M. C., Buo A. M., Garcia-Pelagio K. P., Stains J. P., and Bloch R. J.. 2016. Deficiency of the intermediate filament synemin reduces bone mass in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 311:C839–C845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr M. A., Nicol C. J., and Murrell J. C.. 2012. Do laying hens with keel bone fractures experience pain?PLoS ONE 7:e42420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosavanh L., Yu D.-H., Jaehnig E. J., Tong Q., Shen L., and Chen M.-H.. 2015. Cell-autonomous activation of Hedgehog signaling inhibits brown adipose tissue development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112:5069–5074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda B., Laporta P., Cano A., and García-Pérez M. A.. 2008. The Asn19Lys substitution in the osteoclast inhibitory lectin (OCIL) gene is associated with a reduction of bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 82:348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddell C. 1992. Non-infectious skeletal disorders of poultry: An overview. In: C. C. Whitehead, editor. Bone Biology and Skeletal Disorders in Poultry. Abingdon, UK: Carfax Publishing Co; p. 119–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sparke A., Sims T., Avery N., Bailey A., Fleming R., and Whitehead C.. 2002. Differences in composition of avian bone collagen following genetic selection for resistance to osteoporosis. Br. Poult. Sci. 43:127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratmann A., Fröhlich E., Gebhardt-Henrich S., Harlander-Matauschek A., Würbel H., and Toscano M. J.. 2016. Genetic selection to increase bone strength affects prevalence of keel bone damage and egg parameters in commercially housed laying hens. Poult. Sci. 95:975–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum S. L. 2000. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 289:1504–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viguet-Carrin S., Garnero P., and Delmas P.. 2006. The role of collagen in bone strength. Osteoporos. Int. 17:319–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren D. C. 1937. Physiologic and genetic studies of crooked keels in chickens. Technical Bulletin 44. Manhattan, Kansas: Kansas State College press; p. 32.

- Weber R., Nogossek M., Sander I., Wandt B., Neumann U., and Glunder G.. 2003. Investigations of laying hen health in enriched cages as compared to conventional cages and a floor pen system. Wien. Tierarztl. Monatsschr. 90:257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Weedon M. N., Purcell S., Lettre G., Estrada K., Willer C. J., Smith A. V., Ingelsson E., O’connell J. R., and Mangino M.. 2011. Genomic inflation factors under polygenic inheritance. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19:807–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.