Abstract

Background

The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of polyetheretherketone (PEEK) rod systems in patients receiving lumbar interbody fusion treatment. Meta-analyses of relevant clinical data were also conducted when possible.

Methods

Relevant studies were identified by searching the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases. Clinical studies evaluating the safety and/or effectiveness of the PEEK rod spinal stabilization system in patients receiving lumbar spinal fusion procedure were included. Studies regarding dynamic stabilization and hybrid stabilization (fixed and dynamic; eg, topping-off technique) were not included in this analysis. The analyses included patients who had a lumbar fusion procedure with PEEK rods or titanium rods as a control reference (only for controlled studies). Fusion success, functional and pain improvement, and safety data were evaluated, if reported.

Results

The search yielded 5 studies (1 prospective and 4 retrospectives) that included 177 participants (156 received PEEK rods, and 21 received titanium rods). Meta-analysis of interbody fusion success rate in PEEK rod patients yields the estimate of 95.6% (confidence interval: 91.6% to 98.4%). Functional outcomes in PEEK rod patients demonstrated clinically significant improvement when comparing postoperative to preoperative scores, with an average improvement of 67.4% ± 8.5%. Similarly, pain improvement was clinically significant with an average visual analog scores–back pain and visual analog scores–leg pain improvement percentages of 68.9% ± 8.6% and 76.6% ± 1.5%, respectively. Rod fracture was not reported in any of the studies. The rates of screw fracture and loosening were 3/114 (2.6%) and 1/50 (2.0%), respectively. In the controlled study, no statistically significant difference was reported in the fusion success rate, function improvement, pain improvement, or device-related events between subjects treated with PEEK rods and the subjects treated with titanium rods.

Conclusions

Experience with PEEK rod systems has shown satisfactory clinical outcomes. Therefore, these results support the use of PEEK rod systems as supplemental fixation during lumbar fusion procedures.

Keywords: PEEK rod, lumbar fusion, DDD, fusion success, titanium rod, ODI, VAS

INTRODUCTION

Instrumented spinal arthrodesis using rigid rods is currently the most widely used treatment for degenerative diseases of the lumbar spine, particularly if unresponsive to conservative care. However, the elastic modulus of titanium, the main metallic material used in lumbar fusion procedures, is much greater than that of bone, which may significantly change the physiological distribution of the load at the instrumented vertebral segments.1–3

Semirigid systems have been proposed to avoid rigid fixation to prevent adjacent segment degeneration. Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) rods have become available as an alternative to metal rods for use with pedicle screws to perform posterior lumbar fusion. PEEK has a modulus of elasticity between that of cortical and cancellous bones, thus mimicking the features of the physiological environment.3–5 Additionally, PEEK rods are associated with a substantial reduction in stress-shielding characteristics, which reduces the stress on the pedicle screws and may decrease the risk of failure, especially in osteoporotic bone.3,5 Furthermore, PEEK is translucent to X-rays, so these rods cause fewer artifacts on computed tomography scans making radiologic follow-up easier.6

Two reviews were previously published on the use of PEEK rod systems for spine disorders.7,8 However, the authors of both studies did not analyze the fusion and dynamic stabilization data separately. Since the differences in patient population, indications, and biomechanics in these 2 groups (fusion patients versus dynamic stabilization patients) may impact the quality and/or the value/usability of the data, this project was conducted to evaluate the clinical data in lumbar fusion patients only (ie, no dynamic stabilization data were included in our analyses). In this study, we analyzed fusion success rates, pain/function improvement data, and device-related data in patients who received PEEK rods for interbody fusion (IBF). Subgroup analyses included fusion rates per number of treated levels, and per graft type. These analyses were used to appraise the risk-benefit profile of PEEK rods in lumbar IBF indication.

METHODS

Search Strategy and Study Selection

A literature search of the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases was conducted independently by 2 authors (A.S. and S.M.) to identify relevant studies (controlled or not controlled) evaluating the use of PEEK rod spinal stabilization systems in lumbar spine fusion patients. The literature search was completed on July 20, 2017. The search was not restricted by language or date of publication. The following keywords or phrases in various combinations were utilized: PEEK rod or polyetheretherketone rod or semirigid rod or semi-rigid rod or semi rigid rod or CD Horizon. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 2 authors (A.S. and S.M.) identified potentially eligible studies, and full texts of identified articles were examined for eligibility. Exclusion criteria were as follows: dynamic stabilization, topping off/topping down, biomechanical, cadaver, in vitro, or animal studies. Any disagreement was resolved through consensus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of study selection.

Data Extraction and Presentation

Data extraction was independently conducted by 2 assessors (A.S. and F.T.). Any disagreements were resolved through consensus. The following data were extracted: author; year; study type; publication type; mono- or multi-centric study type; surgery dates; number of patients; preoperative pathology/diagnosis; rates of fusion success, rod fracture, screw fracture, and screw loosening; functional outcomes (Japanese Orthopedic Association [JOA] or Oswestry Disability Index [ODI] scores); visual analog score (VAS); surgical procedure; bone graft used; cage used; and follow-up period. Fusion success rates, VAS, functional improvement, rod fracture, screw fracture, and screw loosening data were extracted according to the methods in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data extraction and presentation methods.

|

Item |

Data Presentation Formats in the Articles |

Data Presentation Formats in This Study |

Notes |

| Fusion success rate | Numerator/denominator format (ie, fusion success/total) | Data were presented in numerator/denominator format (ie, fusion success/total). | Fusion success data at the latest endpoint were used for further analysis. |

| Fusion success rates | |||

| Pseudoarthrosis (nonunion) rates | |||

| Functional outcomes (ODI or JOA) | Scores at preoperative and at various postoperative time points | Scores were used to calculate the improvement percentage at the latest time point: (difference between preop score and latest post-op score)/preop score × 100. | In one occasion, data were deduced from the representative graphs and this was indicated at the related table(s). |

| Percentage of improvement at various postoperative time points | |||

| VAS | Scores at preoperative and at various postoperative time points | Scores were used to calculate the improvement percent at the latest time point: (difference between preop score and latest postop score)/preop score × 100. | In some occasions, improvement rates were deduced from their representative graphs and this was indicated at the related table(s). |

| Percentage of improvement at various postoperative time points | |||

| Device-related events (rod fracture, screw fracture, and screw loosening) | Specific adverse events (if any) | In case of reported events, the numerator/denominator format was used | |

| No instrumentation failure | |||

| No device-related events |

Abbreviations: ODI, Oswestry Disability Index score; JOA, Japanese Orthopedic Association score; VAS, visual analog score.

Statistical Analysis

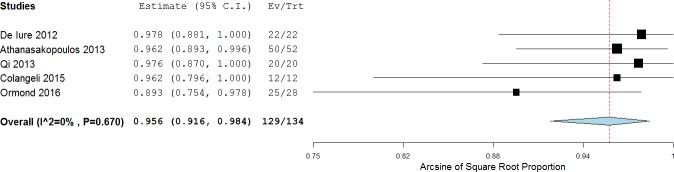

Meta-analysis is the statistical procedure for combining data from multiple studies when the result from a single study is not very reliable or not very convincing. OpenMeta Analyst software9 was employed as a tool for conducting the meta-analysis of the fusion success rates in the noncontrolled studies (Figure 2). Because of the importance of confounding variables such as graft type, and the number of treated levels, subgroup analyses were conducted by including these variables as explanatory variables.

Figure 2.

Forest plot with point estimate (95% confidence interval [CI]) of the fusion success rates established based on binary random effects model in patients treated with interbody fusion along with polyetheretherketone (PEEK) rod systems. The posterolateral fusion cases (8) in De Iure et al.16 were not included in this meta-analysis.

Descriptive statistics were used for assessment of the device-related events as well as ODI, JOA, and VAS data.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Analyzed Articles

As shown in Figure 1, potentially eligible studies were identified by electronic search. After excluding duplicates, 243 records were selected. 228 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria based on their titles and abstracts. It is important to mention that the dynamic stabilization studies10–12 or the hybrid stabilization studies13,14 were not included. After reviewing the full text, 5 studies were finally included for the quantitative analysis.

The analyses included 1 prospective and 4 retrospectives studies. One study included a titanium rod control group. The follow-up period varied from 12 months up to 36 months, with an average follow-up time of 24.1 ± 11.3 months. All studies reported patient-related outcomes with evidence levels of III and IV according to the North American Spine Society classification system.15 For additional details, please see Tables 2 to 4.

Table 2.

List of the analyzed studies.

|

Author |

Year |

Cohort |

PEEK Rod Patients |

Control Patients (Using Titanium Rods) |

Total |

Extracted Outcomesa |

| De Iure et al.16 | 2012 | Retrospective | 30 | NA | 30 | S, F |

| Athanasakopoulos et al.17 | 2013 | Retrospective | 52 | NA | 52 | S, F, V, FI |

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | Prospective | 20 | 21 (titanium) | 41 | S, F, V, FI |

| Colangeli et al.19 | 2015 | Retrospective | 12 | NAa | 12 | S, F, V, FI |

| Ormond et al.20 | 2016 | Retrospective | 42 | NA | 42 | S, F |

| Summary | 1 prospective, 4 retrospective | 156 | 21 | 177 |

Abbreviations: PEEK, polyetheretherketone; S, safety data; V, visual analog score data; F, fusion data; FI, functional improvement data (Oswestry Disability Index or Japanese Orthopedic Association scores).

12 patients who used Nflex rods were not included in any analysis because they are not comparable to PEEK or titanium rods.

Table 4.

High-level summary of the analyzed studies.

|

Item |

Summary |

Notes |

| Total no. of studies | 5 | |

| Total no. of PEEK rod patients | 156 | Total no. including control patients is 177 |

| Monocentric studies | 5/5 | |

| Prospective studies | 1/5 | |

| Retrospective studies | 4/5 | |

| Studies with titanium control group | 1/5 |

Abbreviation: PEEK, polyetheretherketone.

Table 3.

Literature appraisal.

|

Author |

Year |

Device- Related Data |

Patient- Related Data |

Evidence Level15 |

| De Iure et al.16 | 2012 | + | + | IV |

| Athanasakopoulos et al.17 | 2013 | + | + | IV |

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | + | + | III |

| Colangeli et al.19 | 2015 | + | + | III |

| Ormond et al.20 | 2016 | + | + | IV |

Study Patients

The studies included 156 PEEK rod patients with an average age of 52.8 ± 6.5 years. The average percentage of females was 44.5% ± 5.8%. Average follow-up period was 24.1 ± 11.3 months. The preoperative diagnoses/pathologies included stenosis, segmental instability, recurrent disc herniation, spondylolisthesis, axial back pain with lower extremity weakness, vertebral fracture, and tumor (Table 5).

Table 5.

Baseline data of the PEEK rod-treated patients.

|

Author |

Year |

Patient Population (Diagnoses/Preoperative Pathology) |

Age Mean (y) |

Female (m/n, %) |

Follow-Up Period Mean (mo) |

| De Iure et al.16 | 2012 | Multilevel spinal stenosis with claudication, segmental spinal stenosis, symptomatic low-grade spondylolisthesis, painful DDD, and recurrent disc herniation | 61 | 17/30, 56.7 | 12 |

| Athanasakopoulos et al.17 | 2013 | DDD (25), lateral recess stenosis (10), combined lateral recess stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis (4), degenerative spondylolisthesis (6), lumbar spine vertebral fracture (6), and an L5 giant cell tumor (1) | 55.4 | 29/52, 55.8 | 36 |

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | Lumbar disc herniation with segmental instability, lumbar spondylotic stenosis with segmental instability, or low-grade degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. | 50.4 for PEEK, 48.9 for control | 9/20, 45.0% for PEEK, and 10/21, 47.6% for control | 12 |

| Colangeli et al.19 | 2015 | All patients presented lumbar DDD with spondylolisthesis, disc herniation, or stenosis. | 43.3 | 3/12, 25.0 | 29.1 |

| Ormond et al.20 | 2016 | Axial back pain with or without radiculopathy and lower extremity weakness | 53.7 | 17/42, 40.5 | 31.4 |

| Summary | 52.8 ± 6.5a | 44.6% ± 13.0a | 24.1 ± 11.3 |

Abbreviations: PEEK, polyetheretherketone; DDD, degenerative disc disease.

Based on the PEEK subjects, not including the control subjects.

Surgical Techniques and Procedures

Lumbar IBF was used in most of the studies (Table 6). The open surgical technique was used in all studies. The studies included the use of various graft types and the treatment of single as well as multiple levels. The following bone grafts were used: autograft alone and autograft mixed with demineralized bone matrix (DBM). Fusion success rate analyses were conducted for IBF only. For additional details, see Tables 6 and 7.

Table 6.

Overall summary of the fusion data in PEEK rod–treated patients.

|

Author |

Year |

PEEK Rod Patients (n) |

Raw Data |

No. of Successful Fusions/Total No. (%) |

Graft Type |

Fusion Procedure |

No. of Treated Levels |

| De Iure et al.16 | 2012 | 30 | In the group of 22 patients in whom anterior interbody cages were implanted, a clear fusion was visible in 18 patients at 6 months and in all the patients at 12 months. | IBF: 22/22 (100.0%), PLF: 7/8 (87.5%) | AG | IBF (22); PLF (8) | 2.9 (average), range: 2–5 |

| In the 8 patients who received posterolateral autogenous grafting only, 4 patients were fused at 6 months and 7 patients at 1 year. | |||||||

| Athanasakopoulos et al.17 | 2013 | 52 | Imaging evidence of new bone formation was observed in 50 (96%) patients by 1-year follow-up; 2 patients developed no imaging signs of union during follow-up. | 50/52 (96.2%) | AG + DBM | IBF | 1 (10), 2 (29), 3 (13) |

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | 20 | The overall fusion rate was 100.0 % at the 1-year follow-up for both groups. | 20/20 (100.0%) | AG | IBF | 1(20) |

| Colangeli et al.19 | 2015 | 12 | All the patients presented bony fusion at 6-month follow-up. | 12/12 (100.0%) | NR | IBF | 1 (9), 2 (3) |

| Ormond et al.20 | 2016 | 42 | Fusion data were available for 28 patients only, 25 of whom demonstrated fusion (89.3%). All patients radiographically fused were confirmed by CT scan. | 25/28 (89.3%) | AG + DBM | IBF | 1(42) |

| Summary | 156 | Fusion data are available for 142 patients: | NS: 7.7% (12/156), AG: 32.1% (50/156), AG + DBM: 60.3% (94/156) | IBF: 94.9% (148/156), PLF: 5.1% (8/156) | |||

| IBF rate based on pooled data: 96.3% (129/134) | |||||||

| PLF rate: 87.5% (7/8) |

Abbreviations: PEEK, polyetheretherketone; IBF, interbody fusion; PLF, posterolateral fusion; AG, autograft; DBM, demineralized bone matrix; NS, not specified; CT, computed tomography; NR, not reported.

Table 7.

Details on the number of treated levels and graft types in patients received interbody fusion using PEEK rods.

|

Author |

Year |

PEEK Rod Patients (n) |

1 Level (n) |

2 Levels (n) |

3 Levels (n) |

Not Specified Multiple Levels (n) |

Graft Type |

| DeIure et al.16 | 2012 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | AG |

| Athanasakopoulos et al.17 | 2013 | 52 | 10 | 29 | 13 | 0 | AG + DBM |

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | AG |

| Colangeli et al.19 | 2015 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | NR |

| Ormond et al.20 | 2016 | 28 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | AG + DBM |

| Total | 134 | 67 | 32 | 13 | 22 |

Abbreviations: PEEK, polyetheretherketone; AG, autograft; DBM, demineralized bone matrix; NR, not reported.

Safety Results

Device-related events (rod fracture and screw loosening/fracture) were extracted and analyzed for PEEK rod–treated subjects. Rod fracture was not reported in any of the studies. The rates of screw fracture and loosening were 3/114 (2.6%) and 1/50 (2.0%), respectively. The rates of screw fracture ranged from 0.0% to 3.8% and the rates of screw loosening ranged from 0.0% to 3.3% (Table 8). Data from the controlled studies demonstrated no statistically significant difference in the rates of device-related events in the PEEK treatment group as compared to that in the titanium control group (Table 9).

Table 8.

Summary of device-related events in PEEK rod patients.

|

Author |

Year |

Total No. of PEEK Patients |

Raw Data |

Extracted Data |

||

|

Patients With Rod Fractures (n) |

Patients With Screw Fracture (n) |

Patients With Screw Loosening (n) |

||||

| De Iure et al.16 | 2012 | 30 | Only one case required surgical revision for a mechanical complication; one patient exhibited screw mobilization at 8-month follow-up. | NS | NS | 1/30 (3.3%) |

| Athanasakopoulos et al.17 | 2013 | 52 | Two patients sustained screw breakage. | NS | 2/52 (3.8%) | NS |

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | 20 | No complications from instrumentation were noted. Neither screw displacement nor screw failure was detected in any of the patients at the follow up. | NS | 0/20 (0.0%) | 0/20 (0.0%) |

| Colangeli et al.19 | 2015 | 12 | No patient had any complications. | NS | NS | NS |

| Ormond et al.20 | 2016 | 42 | Reasons for reoperation included instrumentation failure from a fractured screw (1). | NS | 1/42 (2.4%) | NS |

| Total | 156 | 3/114 (2.6%)a | 1/50 (2.0%)a | |||

Abbreviations: PEEK, polyetheretherketone; NS: not specified. NS implies that results did not indicate the occurrence of this event. However, authors did not give enough specific details sufficient to extract numerical data.

Denominators vary according to the data availability for each category.

Table 9.

Summary of device-related events in the controlled studies (PEEK versus titanium rods).

|

Study |

Year |

Raw Data |

Extracted Data |

||||||||

|

Titanium |

PEEK |

Titanium-PEEK Rate of Difference |

|||||||||

|

SL |

SF |

RF |

SL |

SF |

RF |

SL |

SF |

RF |

|||

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | Neither screw displacement nor screw failure was detected for any of the patients at the follow-up. No titanium alloy rod failure was found in the titanium group. | 0/21 (0.0%) | 0/21 (0.0%) | 0/21 (0.0%) | 0/20 (0.0%) | 0/20 (0.0%) | NS | 0.0% | 0.0% | NA |

Abbreviations: PEEK, polyetheretherketone; SL, screw loosening; SF, screw fracture; RF, rod fracture; NS, not specified; NA, not applicable.

Effectiveness Results

Fusion Success Rate

Fusion success rates were reported for 142 PEEK rod patients in 5 studies. Most of these patients received IBF (134/142; 94.4%). The remaining patients (8/142; 5.6%) received posterolateral fusion (PLF). In this review, fusion success rate analyses were conducted for IBF only.

The meta-analysis estimate for fusion success rate in patients having IBF is 95.6% (confidence interval: 91.6% to 98.4%) (Table 6; Figure 2). It is important to mention that the lowest fusion success rate was reported in Ormond et al. (89.3%).20 However, this particular study had a high percentage of smokers (42.8%), and we observed that 2 out of the 3 nonfusion cases were smokers,20 which could be the reason for a relative lower fusion success rate than the other studies.

Because of the importance of confounding variables such as graft type and the number of treated levels, we further conducted subgroup analyses for these 2 variables. Slightly higher fusion success rate was observed in studies having IBF with autograft only compared to autograft and DBM (97.7% versus 93.9%, respectively) (Figure 3). Regarding the number of treated levels, since no patient-level fusion data were available, a conservative approach was used by classifying the studies into 2 subgroups: studies that included only single-level–treated patients (SL) versus studies that included single as well as multiple-level–treated patients (ML). Similar fusion success rates were observed in SL and ML studies; point estimates of 93.8% and 95.6%, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Forest plot with point estimate (95% confidence interval [CI]) of the fusion success rates established based on binary random effects model in patients treated with interbody fusion along with polyetheretherketone (PEEK) rod systems per graft type. Abbreviations: AG, autograft only; AGD, autograft + demineralized bone matrix.

Figure 4.

Forest plot with point estimate (95% confidence interval [CI]) of the fusion success rates established based on binary random effects model in patients treated with interbody fusion along with polyetheretherketone (PEEK) rod systems per the number of treated levels. Abbreviations: SL, the study included only single-level–treated patients; ML, the study included single as well as multiple-level–treated patients.

Fusion Data in the Controlled Studies

Qi et al.18 reported 100% fusion rates in both treatment groups. Meta-analysis assessment was not feasible because of lack of enough study number. For additional information, please see Table 10.

Table 10.

Fusion data in the controlled studies (PEEK versus titanium rods).

|

Study |

Control (n), Fusion Rate (%) |

PEEK (n), Fusion Rate (%) |

Notes |

| Qi et al.18 | 21/21 (100.0%) | 20/20 (100.0%) | The overall fusion success rate was 100.0% at the 1-year follow-up for both groups. |

Abbreviation: PEEK, polyetheretherketone.

Functional Improvement Outcomes in PEEK Rod Patients

Functional improvement data were reported in 3 out of the 5 studies (Table 11). Functional improvement data were presented as scores (pre- and postoperative scores at various time points) or as percentage of improvement of ODI (2 studies) or JOA (1 study) scores. To have comparable data, we calculated the percentage of improvements as the difference between pre- and postoperative scores/(preoperative score × 100). In these 3 studies, PEEK rod patients (84) had clinically significant improvement when comparing postoperative to preoperative scores, with an average improvement of 67.4% ± 8.5% (Table 11). Meta-analysis was not feasible due to the lack of essential numerical data (SD or SE).

Table 11.

Overall summary of the functional improvement data in PEEK rod patients.

|

Author |

Year |

Functional Test |

PEEK Rod Patients (n) |

Raw Data at the Last Available Follow-Up |

Extracted Data: Functional Improvement at the Last Available Follow-Up (%) |

| Athanasakopoulos et al.17 | 2013 | ODI | 52 | Preop: 76.0; 12 months: 30.0 | 60.5 |

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | JOA | 20 | Data were reported as percentage at 12 months | 76.9 |

| Colangeli et al.19 | 2015 | ODI | 12 | Preop: 68.0; 12 months: 24.0 | 64.7 |

| Total | 84 | Mean = 67.4 ± 8.5 | |||

| Median = 64.7 | |||||

| Min = 60.5; Max = 76.9 |

Abbreviations: PEEK, polyetheretherketone; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index score; JOA, Japanese Orthopedic Association score.

Functional Improvement in the Controlled Studies

Qi et al.18 reported that clinically meaningful improvement was observed in both groups when comparing the preoperative to the postoperative data (Table 12). Additionally, the authors reported that there was no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups (Table 12). Meta-analysis was not feasible due to the lack of sufficient number of studies.

Table 12.

Functional improvement data in the controlled studies (PEEK versus titanium rods).

|

Author |

Year |

No. of Patients |

Average Improvement (%) |

Functional Test |

Notes |

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | 20 PEEK, 21 titanium | At 1 year: 76.9% PEEK versus 77.6% titanium | JOA | At 1 year, no statistically significant difference was observed (P > .05) |

Abbreviation: PEEK, polyetheretherketone; JOA, Japanese Orthopedic Association.

Pain Improvement Outcomes in PEEK Rod Patients

Pain improvement data of PEEK rod patients were reported in 3 out of 5 studies (Table 13). Pain improvement data were presented as scores (pre- and postoperative scores at various timepoints) or as percentage of improvement. To have comparable data, we calculated the percentages of improvement as the difference between pre- and postoperative scores/(pre-operative score × 100). In all studies, PEEK patients had clinically meaningful improvement when comparing postoperative to preoperative data (Table 13). Two17,18 out of those 3 studies reported detailed pain data: visual analog scores–back pain (VAS-BP) and visual analog scores–leg pain (VAS-LP) data. Average VAS-BP and VAS-LP improvement percentages of 68.9% ± 8.6% and 76.6% ± 1.5%, respectively, were observed (Table 13). In the third study,19 overall pain improvement of 57.9% was reported. Meta-analysis was not feasible due to the lack of sufficient number of studies.

Table 13.

Summary of the pain improvement data in PEEK rod patients.

|

Author |

Year |

PEEK Rod Patients (n) |

Pain Improvement Raw Data |

Extracted Data: VAS Improvement at the Last Follow-Up (%) |

| Athanasakopoulos et al.17 | 2013 | 52 | VAS-BP: Preop = 8; at 36 months = 2 | VAS-BP: 75.0% |

| VAS-LP: Preop = 9; at 36 months = 2 | VAS-LP: 77.7 % | |||

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | 20 | VAS-BP: Preop = 7.0; at 12 months = 2.6 VAS-LP: Preop = 7.4; at 12 months = 1.8 The analysis of variance revealed that clinical VAS-BP, and VAS-LP scores improved significantly at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively compared with the preoperative scores (P < .001) Note: Preoperative data were taken from Qi et al.18, table 1 and postoperative data were deduced from graphs in Qi et al.18 figures 1 and 2. |

VAS-BP: 62.8% VAS-LP: 75.6% |

| Colangeli et al.19 | 2015 | 12 | VAS: Preop = 9.5; at 12 months = 4.0 | 57.9% |

| Summary | Total = 84 | VAS-BP: Mean = 68.9 % ± 8.6%, Median = 68.9%, Min = 62.8%, Max = 75.0% | ||

| VAS-LP: Mean = 76.6% ± 1.5%, Median = 76.6%, Min = 75.6%, Max = 77.7% |

Abbreviations: PEEK, polyetheretherketone; VAS-BP, visual analog scores–back pain; VAS-LP, visual analog scores–leg pain.

Pain Improvement in the Controlled Studies

Qi et al.18 reported VAS-BP and VAS-LP scores separately. VAS-LP scores improved significantly at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively compared with the preoperative scores (P < .001) in both groups. No significant differences were seen between the treatment groups at the same time points (P > .05) (Table 14).

Table 14.

VAS improvement data in the controlled studies (PEEK versus titanium rods).

|

Author |

Year |

Total No. of Patients |

VAS Improvement Mean (%) |

Notes |

| Qi et al.18 | 2013 | 20 PEEK, 21 titanium | PEEK VAS-BP: Preop = 7.0; at 12 months = 2.6 | VAS-LP scores improved significantly at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively compared with the preoperative scores (p < 0.001) in both groups. In the PEEK group, patients showed a similar extent of improvement respectively in VAS-BP and VAS-LP scores at the same time points postoperatively as compared to patients in the TI group (p > 0.05). |

| Titanium VAS-BP: Preop = 6.5; at 12 months = 2.8 | ||||

| PEEK VAS-LP: Preop = 7.4; at 12 months = 1.8 | ||||

| Titanium VAS-LP: Preop = 7.2; at 12 months = 1.6a | ||||

| VAS-BP improvement at 12 months: ∼63.4% for the titanium group and ∼66.2% for the PEEK. | ||||

| VAS-LP improvement: ∼72.0% for the titanium group and 73.2% for the PEEK.b |

Other Findings

Disc Height (DH)

Qi et al.18 examined DH preoperatively and postoperatively. DH increased significantly at 1 week and 1 year postoperatively compared with the preoperative data (P < .01) in both groups (PEEK and titanium). Patients in the PEEK group showed no significant differences in disc space height at 1 week and 1 year postoperatively as compared with patients in the titanium group (P > .05). Moreover, the increase rate of disc space height at 1 week postoperatively (defined as [1-week postoperative DH − preoperative DH]/preoperative DH × 100%) and the loss rate of DH at 1 year postoperatively (defined as [1-week postoperative DH − 1-year postoperative DH]/1-week postoperative DH × 100%) were calculated. The postoperative increase of DH and loss of DH during the follow-up showed a similar extent of change between both groups (P > .05). Authors concluded that the loss of DH could be found during the follow-up in PEEK group, but the extent of loss was similar to titanium group and therefore PEEK rods could meet the requirement in keeping lumbar lordosis and DH.18

Quality of Life (QoL)

Colangeli et al.19 reported a highly significant improvement in the life quality in PEEK rod–treated patients. In 12 cases treated by PEEK rods and IBF the average preoperative QoL value was 24 (range 0 to 60); the average postoperative QoL value was 74 (range 60 to 90, P = .0002).19 These data are in alignment with the functional improvement outcomes.

Retrieval Analysis of PEEK Rods

As part of a prospective study organized to analyze explanted spinal devices and associated periprosthetic tissues collected at revision surgery, Kurtz and colleagues21 evaluated explanted PEEK rod spinal systems in the context of their clinical indications. Damage to the implant and histological changes in explanted periprosthetic tissues were evaluated. Retrieved components were assessed for surface damage mechanisms, including plastic deformation, scratching, burnishing, and fracture. Patient history and indications for PEEK rod implantation were obtained from analysis of the medical records.21

Twelve patients with PEEK rods underwent revision surgery, and their posterior instrumentation was retrieved. Patient age ranged from 35 to 64 years (mean ± SD: 52 ± 10 years); 8 patients (66.7%, 8/12) were female, and the implantation time of the PEEK rods ranged from 0.5 to 2.8 years (mean ± SD: 1.7 ± 0.8 years).21

All the patients in this study were revised for intractable pain, although the mechanism varied and was confirmed by intraoperative findings. The most frequently reported reasons (58.0%, 7/12) for revision among the PEEK rod patients who underwent spinal fusion included adjacent segment disease in 3 patients, device-related muscular paravertebral pain in 2 patients, and pseudoarthrosis in 2 patients. The revision procedures were performed via a posterior approach.21

Eleven of the 12 PEEK rod systems were employed for fusion at one level and motion preservation at the adjacent level. There were no cases of PEEK rod fracture or pedicle screw fracture. Retrieved PEEK rods exhibited scratching, as well as impressions from the set screws and pedicle screw saddles. PEEK debris was observed in 2 patient tissues, which were located adjacent to PEEK rods with evidence of scratching and burnishing. Kurtz and colleagues21 did not attribute any complications to this PEEK debris.

Kurtz and colleagues21 concluded that PEEK rods were associated with similar clinical risks to those posed by traditional metal rod systems used for posterior lumbar fusion, and that the reasons for PEEK rod system revisions, including pseudoarthrosis, device-related pain, disease progression, and unrecognized adjacent-level disease, were well documented in the literature for metallic posterior fusion systems. Because their study was limited to a relatively small number of cases requiring surgical intervention and instrumentation removal, Kurtz and colleagues21 also concluded that their study could not be used to establish the overall revision or complication risk for the clinical use of PEEK rods. Moreover, many of their cases were salvage procedures with a history of previous spinal surgeries, which were more difficult than primary fusions. Kurtz and colleagues21 stated, nevertheless, that the findings from this relatively small series of revision cases were a positive complement to the data obtained in prospective clinical studies.21

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the use of PEEK rods in the IBF procedures. The systematic review included 5 studies and analyzed the following data: the rates of rod fracture, screw fracture, and screw loosening; fusion success rates; and the percentages of pain and function improvement (Tables 2 to 4).

No rod fractures were reported in any study, and the average rates of screw fractures and screw loosening were 2.6% and 2.0%, respectively (Table 8). In the controlled study, no significant difference between these rates was reported (Table 9).

The estimate of IBF success rate was 95.6% (Table 6; Figure 2). In the controlled study,18 the fusion success rate was 100.0% in both treatment groups (Table 10). The possible confounding effect of the graft type and the number of the treated levels on the fusion success rates was examined, and no significant difference was observed (Table 7, Figures 3 and 4).

When comparing preoperative to postoperative function scores, PEEK rod patients demonstrated clinically meaningful improvement with an average improvement of 67.4% (Table 11). Additionally, the functional improvement magnitudes in the controlled study18 were similar in the PEEK and titanium groups (Table 12).

PEEK rod patients had significant VAS improvements when comparing pre- to postoperative scores at an average change of 68.9% and 76.6% for VAS-BP and VAS-LP, respectively (Table 13). Moreover, the controlled study VAS data showed no significant difference between titanium and PEEK rod–treated patients (Table 14).

Our inferences are in agreement with the findings of other individual studies and reviews.7,8 Mavrogenis et al.7 evaluated the use of PEEK rod systems for spine stabilization. Their review discussed the effect of this device in fusion and nonfusion spine stabilization procedures. The authors concluded that early practice with PEEK rod systems has shown biomechanical compliance with physiological spinal movement, increased fusion success rates, minimum complications, and reduced adjacent segment degeneration. The authors noted that these results reserve a significant place for the use of PEEK in spinal surgery.7

Li et al.8 conducted a systematic review to evaluate the use of PEEK rod systems in fusion and nonfusion spine stabilization procedures. No single PEEK rod break was reported and the IBF rate varied from 89.3% to 100%. Li concluded that PEEK rod systems can be used for semirigid fusion for the treatment of degenerative disc disease and mild lumbar spondylolisthesis.8

It is important to note that this study has some shortcomings, including the small number of studies (5), and their low evidence levels (III and IV). However, this report may lay the foundation for higher-level studies in the future.

In summary, the data demonstrated satisfactory fusion success rates and clinically meaningful percentages of functional and pain improvements as well as low rates of device-related events. These outcomes suggest that there are sufficient foundations to support the use of PEEK rods as an adjunct to IBF.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kurtz SM, Devine JN. PEEK biomaterials in trauma, orthopedic, and spinal implants. Biomaterials. 2007;28(32):4845–4869. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narayan P, Haid RW, Subach BR, Comey CH, Rodts GE. Effect of spinal disease on successful arthrodesis in lumbar pedicle screw fixation. J. Neurosurg. 2002;97(3 Suppl):277–280. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.97.3.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponnappan RK, Serhan H, Zarda B, Patel R, Albert T, Vaccaro AR. Biomechanical evaluation and comparison of polyetheretherketone rod system to traditional titanium rod fixation. Spine J. 2009;9(3):263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Highsmith JM, Tumialan LM, Rodts GE., Jr Flexible rods and the case for dynamic stabilization. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(1):E11. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.22.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavagna R, Tournier C, Aunoble S, Bouler JM, Antonietti P, Ronai M, et al. Lumbar decompression and fusion in elderly osteoporotic patients: a prospective study using less rigid titanium rod fixation. J. Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(2):86–91. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3180590c23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarbello JF, Lipman AJ, Hong J, et al. Patient perception of outcomes following failed spinal instrumentation with polyetheretherketone rods and titanium rods. Spine. 2010 Aug 1;35(17):E843–E848. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d95316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mavrogenis AF, Vottis C, Triantafyllopoulos G, Papagelopoulos PJ, Pneumaticos SG. PEEK rod systems for the spine. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol: Orthopedie Traumatologie. 2014;24(Suppl 1):S111–S116. doi: 10.1007/s00590-014-1421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li C, Liu L, Shi JY, Yan KZ, Shen WZ, Yang ZR. Clinical and biomechanical researches of polyetheretherketone (PEEK) rods for semi-rigid lumbar fusion: a systematic review. Neurosurg Rev. 2018;41(2):375–389. doi: 10.1007/s10143-016-0763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace BC, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA, Lau J, Trow P, Schmid CH. Closing the gap between methodologists and end-users: R as a computational back-end. J Stat Software. 2012;49(5):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang W, Chang Z, Song R, Zhou K, Yu X. Non-fusion procedure using PEEK rod systems for lumbar degenerative diseases: clinical experience with a 2-year follow-up. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2016;17(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-0913-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enercan MGB, Kahraman S, Cobanoglu M, et al. Clinical results of dynamic stabilization adjacent to fusion level: a new lumbar hybrid instrumentation. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(6, Suppl. 1):S764. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bono CM, Kadaba M, Vaccaro AR. Posterior pedicle fixation-based dynamic stabilization devices for the treatment of degenerative diseases of the lumbar spine. J. Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(5):376–383. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31817c6489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pape H, Ringel F, Behr M, Meyer B, Stoffel M. Feasibility, safety and efficacy using peek rods with interbody graft support for a topping-off technique in a hybrid-system for dorsal stabilization of lumbar instabilities—preliminary results of a prospective single-center observation. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(11):P159. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pape HRF, Obermüller T, Wostrack M, Kuhlen D, Meyer B. Hybrid stabilization with rigid levels and ‘topping-off' for multi-level degenerative lumbar instabilities-preliminary results of a series of 173 consecutive patients. 64th Annual Meeting of the German Society of Neurosurgery (DGNC) 2013.

- 15.North American Spine Society. Levels of Evidence For Primary Research Question as Adopted by the North American Spine Society. 2005 https://www.spine.org/Documents/ResearchClinicalCare/LevelsOfEvidence.pdf.

- 16.De Iure F, Bosco G, Cappuccio M, Paderni S, Amendola L. Posterior lumbar fusion by peek rods in degenerative spine: preliminary report on 30 cases. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(Suppl):S50–S54. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2219-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Athanasakopoulos M, Mavrogenis AF, Triantafyllopoulos G, Koufos S, Pneumaticos SG. Posterior spinal fusion using pedicle screws. Orthopedics. 2013;36(7):e951–e957. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130624-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi L, Li M, Zhang S, Xue J, Si H. Comparative effectiveness of PEEK rods versus titanium alloy rods in lumbar fusion: a preliminary report. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2013;155(7):1187–1193. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1772-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colangeli S, Barbanti Brodano G, et al. Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) rods: short-term results in lumbar spine degenerative disease. J Neurosurg Sci. 2015;59(2):91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ormond DR, Albert L, Jr, Das K. Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) rods in lumbar spine degenerative disease: a case series. Clin Spine Surg. 2016;29(7):E371–E375. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318277cb9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtz SM, Lanman TH, Higgs G, et al. Retrieval analysis of PEEK rods for posterior fusion and motion preservation. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(12):2752–2759. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2920-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]