Abstract

Introduction

Infective endocarditis is a serious disease condition. Depending on the causative microorganism and clinical symptoms, cardiac surgery and valve replacement may be needed, posing additional risks to patients who may simultaneously suffer from septic shock. The combination of surgery bacterial spreadout and artificial cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surfaces results in a release of key inflammatory mediators leading to an overshooting systemic hyperinflammatory state frequently associated with compromised hemodynamic and organ function. Hemoadsorption might represent a potential approach to control the hyperinflammatory systemic reaction associated with the procedure itself and subsequent clinical conditions by reducing a broad range of immuno-regulatory mediators.

Methods

We describe 39 cardiac surgery patients with proven acute infective endocarditis obtaining valve replacement during CPB surgery in combination with intraoperative CytoSorb hemoadsorption. In comparison, we evaluated a historical group of 28 patients with infective endocarditis undergoing CPB surgery without intraoperative hemoadsorption.

Results

CytoSorb treatment was associated with a mitigated postoperative response of key cytokines and clinical metabolic parameters. Moreover, patients showed hemodynamic stability during and after the operation while the need for vasopressors was less pronounced within hours after completion of the procedure, which possibly could be attributed to the additional CytoSorb treatment. Intraoperative hemoperfusion treatment was well tolerated and safe without the occurrence of any CytoSorb device-related adverse event.

Conclusions

Thus, this interventional approach may open up potentially promising therapeutic options for critically-ill patients with acute infective endocarditis during and after cardiac surgery, with cytokine reduction, improved hemodynamic stability and organ function as seen in our patients.

Keywords: Cardiopulmonary bypass, Cytokines, CytoSorb, Hemoadsorption, Infective endocarditis

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a serious heart disease caused by microorganisms that enter the bloodstream and settle on the endocardium, heart valves or intracardiac devices. The cardiac effects of IE may include severe valve dysfunction and myocardial abscesses, which may finally lead to severe congestive heart failure. Therefore, depending on the causative microbes (e.g., staphylococci, enterococci, streptococci) and the clinical symptoms, valve replacement may be indicated for these patients (1, 2). Beside the described intracardiac effects, IE patients are at high risk for developing systemic inflammatory response and septic shock as a result of the bacterial spreadout from valve vegetations. Therefore, a surgical procedure (most often replacement of the affected valve) together with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) in a patient with an underlying IE disease represents an intervention with increased risks. The combination of surgical trauma, bacterial spreadout and artificial CPB surfaces results in a release of key inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and IL-8. This may finally lead to an overshooting systemic hyperinflammatory state, frequently resulting in hemodynamic instability that in turn may induce organ dysfunction such as respiratory failure, acute kidney injury, intestinal ischemia and/or cognitive dysfunction (3). Of note, in case of prolonged CPB surgery, the risk of developing severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) postoperatively may increase even more. Postoperative therapeutic management of these patients includes an appropriate anti-infective therapy in combination with therapeutic approaches maintaining vital organ function.

Since inflammatory mediators are key triggers of inflammation and post-CPB SIRS, intra- or postoperative removal of such mediators from blood using blood purification with a cytokine adsorber has previously been described as an useful approach to control these hyperinflammatory processes, to restore immune homeostasis and potentially to prevent post-CPB SIRS and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (4, 5). Currently, the device most used as an adjunctive treatment to standard therapy in subjects suffering from SIRS, severe sepsis or septic shock to support the removal of cytokines as well as other inflammatory mediators via direct whole blood hemoadsorption is CytoSorb.

Cytosorb (CytoSorbents Corporation) is a polymer bead-based cytokine hemoadsorption cartridge approved in Europe since 2011 that can be used in combination with conventional hemodialysis machines or with CPB systems. In general, with more than 17,000 single treatments performed worldwide to date, CytoSorb application can be considered a safe and biocompatible therapeutic intervention. In this paper we describe the intraoperative application of CytoSorb hemoadsorption in 39 patients during CPB surgery due to IE.

Patients and methods

This case series was conducted in the 12-bed adult cardiothoracic surgery Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at the University Hospital Ulm, Germany. Informed consent for retrospective data evaluation was obtained from all patients or their relatives. From September 2013 until August 2016 we treated and monitored 39 consecutive patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB due to acute infective endocarditis. Patient characteristics, diagnoses and individual surgical procedure details are outlined in Table I. Briefly, all patients underwent urgent or emergency cardiac surgery procedures with CPB application (Tab. I). A CytoSorb adsorber cartridge was integrated in a parallel circuit in post-hemofilter position within the extracorporeal CPB circuit. Anticoagulation was achieved using heparin as standard anticoagulant according to routine procedure. Blood flow rates through the adsorber were kept between 200 and 400 mL/min and patients consistently received only CytoSorb treatment during surgery for the entire CPB time and without exchange of the adsorber. Treatment durations are depicted in Table I. Hemodynamic management with catecholamines (i.e., epinephrine, norepinephrine) and volume therapy was performed according to the standard of care protocol. To assess the therapeutic impact of the hemoadsorption treatment we measured laboratory parameters of inflammation (i.e., IL-6 and IL-8) hemodynamics (vasopressor dose, MAP), metabolic variables (lactate, base excess) as well as the extent of postoperative organ support (mechanical ventilation, ECMO, CRRT). Furthermore, we evaluated severity of illness in all patients preoperatively using the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE II) (6) and additionally assessed the postoperative and 24-hour postoperative Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II score). ICU length of stay as well as ICU and hospital survival were obtained as outcome parameters.

Table I.

Patient Characteristics, Surgery Details, Treatment Modalities and Patient Outcome (Hemoadsorption Group)

| Case | Age | Gender | BMI | Diagnosis | Microbiological findings | Operation procedure | Emergency | Euro SCORE II | CPB time (min) | X clamp time (min) | CytoSorb treatment time (min) | APACHE II postop | APACHE II 24h postop | Mechanical ventilation (days) | ECMO (days) | CRRT (days) | Hydrocortisone | ICU LOS (d) | ICU survival | Hospital survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | M | 20.7 | AV Endocarditis | Staph. aureus | Re-Re ARR, Mechanoconduit | No | 18.96 | 253 | 151 | 253 | 1 | 2 | No | 12 | Yes | Yes | |||

| 2 | 73 | F | 24.8 | AV Endocarditis | Streptococcus mitis/cristatis | Re-AVR | No | 31.14 | 114 | 69 | 115 | 33 | 28 | 1 | No | 7 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 3 | 75 | F | 20.8 | AV Endocarditis | Bio-Conduit ARR, CABG | Yes | 96.73 | 445 | 250 | 445 | 46 | 1 | 1 | No | 1 | No | No | |||

| 4 | 67 | M | 21.3 | AV Endocarditis | Abiotropha defectiva | AVR, abscess removal, CABG-RCA | Yes | 12.75 | 138 | 100 | 138 | 26 | 14 | 1 | No | 7 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 5 | 75 | M | 28.7 | AV Endocarditis | Staph.aureus | AVR | Yes | 4.96 | 71 | 49 | 72 | 1 | No | 9 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 6 | 37 | M | 36.0 | AV Endocarditis | Staph. aureus, Stertococcus pyogenes | AVR | Yes | 16.68 | 112 | 78 | 112 | 24 | 24 | 12 | Yes | 19 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 7 | 52 | M | 26.5 | MV + AV Endocarditis | Streptococcus mitis | MVR, AVR, ARRec, SCAE | No | 9.01 | 200 | 145 | 200 | 1 | Yes | 11 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 8 | 69 | F | 49.5 | MV Endocarditis | Staph. aureus | MVR | Yes | 64.18 | 115 | 70 | 115 | 32 | 26 | No | 32 | No | No | |||

| 9 | 62 | M | 32.3 | MV Endocarditis | Streptococcus viridans | MVR | Yes | 48.24 | 171 | 107 | 142 | 31 | 21 | 2 | 3 | Yes | 6 | Yes | Yes | |

| 10 | 75 | M | 25.1 | MV + AV Endocarditis | Streptococcus mitis | AVR, MVR | Yes | 5.22 | 138 | 104 | 138 | 24 | 12 | 1 | No | 3 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 11 | 75 | F | 22.8 | AV Endocarditis | AVR | Yes | 9.62 | 88 | 60 | 88 | 30 | 15 | 1 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | |||

| 12 | 64 | M | 26.9 | MV Endocarditis | Streptococcus agalactiae | MVR | Yes | 2.21 | 117 | 90 | 116 | 28 | 20 | 2 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 13 | 33 | M | 25.7 | TK Endocarditis | Staph. aureus, fungi | MICTKR | No | 4.43 | 101 | 61 | 102 | 31 | 17 | 1 | No | 5 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 14 | 38 | M | 19.8 | MV Endocarditis | Streptococcus agalactiae | MIC MVR | Yes | 6.2 | 109 | 75 | 91 | 33 | 20 | 1 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 15 | 77 | F | 30.1 | MV Endocarditis | Streptococcus bovis | MVR | Yes | 53.17 | 122 | 89 | 122 | 37 | 33 | 4 | 3 | Yes | 4 | No | No | |

| 16 | 60 | M | 30.0 | AV Endocarditis | AVR, MKR, TKR, RFA | Yes | 12.83 | 204 | 145 | 205 | 32 | 31 | 2 | 4 | Yes | 6 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 17 | 58 | M | 28.4 | MV Endocarditis | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | MVR, 2x CABG | Yes | 12.03 | 132 | 90 | 133 | 30 | 12 | 1 | No | 6 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 18 | 79 | F | 26.8 | MV Endocarditis | Streptococcus mitis | MVR | No | 3.99 | 66 | 45 | 64 | 28 | 18 | 3 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 19 | 62 | F | 27.7 | MV Endocarditis | Staph. aureus | MVR | Yes | 31.46 | 141 | 83 | 141 | 33 | 28 | 7 | 6 | Yes | 13 | Yes | Yes | |

| 20 | 73 | M | 23.5 | AV Endocarditis | Propionibacterium | AVR | No | 4.15 | 101 | 67 | 102 | 32 | 11 | 1 | No | 4 | Yes | No | ||

| 21 | 30 | M | 26.2 | AV Endocarditis | Staph. aureus | Re-AVR, TKE, VA ECMO | Yes | 31.69 | 280 | 129 | 282 | 30 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 1 | Yes | 2 | No | No |

| 22 | 76 | F | 29.3 | MV Endocarditis | Enterococcus faecalis | MVR | No | 74.69 | 159 | 69 | 160 | 33 | 30 | 8 | 4 | 1 | Yes | 8 | No | No |

| 23 | 57 | M | 27.1 | MV Endocarditis | Streptococcus agalactiae | MVR | Yes | 33.1 | 128 | 95 | 128 | 27 | 2 | 3 | Yes | 11 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 24 | 51 | F | 23.4 | AV Endocarditis | Streptococcus mitis | AVR, SCAE | Yes | 4.49 | 224 | 161 | 224 | 25 | 14 | 1 | No | 3 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 25 | 56 | M | 27.0 | AV Endocarditis | Staphylococcus aureus | bio Bentall, CABG, SCAE | No | 9.62 | 340 | 257 | 340 | 22 | 10 | 8 | No | 8 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 26 | 37 | M | 25.0 | AV Endocarditis | Streptokokken | Bentall OP, SCAE, abscess removal | No | 9.01 | 180 | 132 | 180 | 2 | No | 5 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 27 | 59 | M | 24.6 | AV Endocarditis | Staph aureus | Re-AVR, RFA, LAA closure | No | 60.49 | 128 | 74 | 128 | 30 | 23 | 3 | 2 | Yes | 3 | Yes | No | |

| 28 | 48 | M | 23.4 | AV Endocarditis | Enterococcus faecalis | mAVR, mMVR, SCAE | Yes | 11 | 148 | 126 | 148 | 30 | 16 | 1 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 29 | 67 | F | 34.5 | MV + AV Endocarditis | RE AVR, MVR, ARR | No | 50.07 | 302 | 210 | 302 | 36 | 33 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Yes | 2 | No | No | |

| 30 | 60 | F | 44.5 | AV Endocarditis | Staph. aureus | Re-AVR | No | 22.23 | 125 | 84 | 125 | 32 | 13 | 3 | No | 6 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 31 | 77 | M | 23.7 | AV Endocarditis | Enterococcus faecalis | AVR, TKR, RFA, VA ECMO | Yes | 78.23 | 208 | 114 | 208 | 39 | 36 | 7 | 2 | 7 | Yes | 7 | No | No |

| 32 | 51 | M | 30.5 | AV Endocarditis | Streptococcus sanguinis | AVR, SCAE | Yes | 16.17 | 117 | 94 | 116 | 32 | 29 | 1 | No | 5 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 33 | 46 | M | 29.3 | AV Endocarditis | Staph. aureus | AVR | No | 62.96 | 157 | 87 | 157 | 5 | 5 | 5 | No | 5 | No | No | ||

| 34 | 56 | M | 22.6 | AV Endocarditis | Streptococcus agalactiae | AVR | No | 2.15 | 90 | 61 | 90 | 26 | 10 | 1 | No | 3 | Yes | Yes | ||

| 35 | 61 | M | 26.6 | AV prothesis Endocarditis | Re-AVR | No | 5.2 | 134 | 96 | 134 | 19 | 5 | 1 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | |||

| 36 | 68 | M | 39.2 | AV Endocarditis | AVR | Yes | 5.67 | 82 | 54 | 82 | 3 | 3 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 37 | 70 | M | 33.8 | AV Endocarditis | Streptococcus mitis | AVR | Yes | 28.3 | 110 | 73 | 110 | 1 | 3 | No | 10 | Yes | Yes | |||

| 38 | 61 | M | 16.9 | MV Endocarditis | No microbiologiacal finding | MVR, ACVB | Yes | 4.99 | 104 | 66 | 105 | 2 | No | 2 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 39 | 75 | F | 39.7 | MV Endocarditis | Staphylococcus aureus | MVR | No | 55.76 | 131 | 87 | 132 | 31 | 19 | 3 | 3 | No | 11 | Yes | Yes |

ARR = aortic root replacement; AVR = aortic valve replacement; MVR = mitral valve replacement; ARRec = aortic root reconstruction; TKR = tricuspid valve replacement.

In addition we retrieved clinical parameters and outcome data from a historical control group (from the years 2013 and 2014) of patients with infective endocarditis who had surgery with CPB but without CytoSorb hemoadsorption intraoperatively. However, in this group perioperative cytokine levels were not routinely measured and are therefore not available. The data of this comparative historical group are given in Table II.

Table II.

Patient characteristics, surgery details, treatment modalities and patient outcome (comparative historical group)

| Case | Age | Gender | BMI | Diagnosis | Microbiological findings | Operation procedure | Emergency | EuroSCORE II | CPB time (min) | X clamp time (min) | Mechanical ventilation (days) | ECMO (days) | CRRT (days) | Hydrocortisone | ICU LOS (d) | ICU survival | Hospital survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con01 | 57 | M | 31 | MV endocarditis | Staph. Aureus | MVR | Yes | 3.3 | 100 | 59 | 3 | No | 21 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con02 | 72 | M | 26 | AV endocarditis | Granulicatella adiacens | aortic root conduit repair | Yes | 26.0 | 202 | 134 | 26 | 7 | 30 | Yes | 96 | No | No |

| Con03 | 79 | M | 27 | AV endocarditis | Enterococcus faecalis | AVR | No | 23.0 | 190 | 86 | 3 | 10 | No | 9 | Yes | Yes | |

| Con04 | 65 | F | 24 | MV endocarditis | Streptococcus pneumoniae | MVR | Yes | 3.4 | 232 | 75 | 7 | No | 6 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con05 | 75 | M | 23 | MV endocarditis | Streptococcus mitis | MVR, TV repair | No | 14.9 | 127 | 84 | 7 | Yes | 9 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con06 | 64 | M | 30 | AV prothesis endocarditis | none | AVR | Yes | 25.9 | 138 | 96 | 1 | 4 | No | 10 | Yes | Yes | |

| Con07 | 62 | M | 28 | AV endocarditis | Streptococcus gallolyticus | AVR | No | 5.3 | 92 | 63 | 1 | No | 6 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con08 | 59 | M | 23 | MV endocarditis | Staphylococcus aureus | MV repair | Yes | 2.4 | 110 | 67 | 1 | No | 5 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con09 | 56 | M | 26 | AV and MV endocarditis | Streptococcus mitis | AV and MVR | No | 2.2 | 142 | 105 | 1 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con10 | 76 | M | 31 | AV prothesis endocarditis | Enterococcus faecalis | AVR | No | 8.6 | 115 | 86 | 6 | 2 | No | 14 | Yes | Yes | |

| Con11 | 72 | F | 33 | MV prothesis endocarditis, AV endocarditis | Corynebacterium species | MVR, AVR | Yes | 33.9 | 231 | 167 | 8 | 8 | 8 | Yes | 8 | No | No |

| Con12 | 85 | F | 35 | AV prothesis endocarditis | Aerococcus urinae | AVR | No | 16.1 | 143 | 103 | 1 | 4 | No | 7 | Yes | Yes | |

| Con13 | 80 | M | 23 | MV endocarditis | Citrobacter koseri | MVR, AVR | No | 7.5 | 145 | 106 | 4 | Yes | 14 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con14 | 79 | F | 28 | MV endocarditis | Staphylococcus aureus | MVR | No | 24.6 | 164 | 106 | 2 | 7 | Yes | 8 | Yes | Yes | |

| Con15 | 72 | F | 28 | AV endocarditis | Escherichia coli | AVR | No | 4.0 | 39 | 27 | 1 | No | 9 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con16 | 77 | M | 23 | AV endocarditis | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | AVR | No | 10.9 | 116 | 81 | 1 | No | 3 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con17 | 88 | M | 27 | AV endocarditis | Citrobacter koseri | AVR | No | 12.0 | 105 | 66 | 1 | No | 5 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con18 | 82 | F | 21 | MV endocarditis | Escherichia coli | MVR | No | 15.6 | 125 | 90 | 2 | 5 | Yes | 12 | Yes | Yes | |

| Con19 | 75 | F | 21 | MV endocarditis | Steptococcus mutans | MVR | No | 11.8 | 120 | 80 | 1 | 3 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | |

| Con20 | 51 | M | 29 | MV endocarditis | Staphylococcus lugdunensis, Enterococcus faecalis | MVR | No | 3.3 | 108 | 72 | 2 | No | 6 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con21 | 37 | M | 26 | TV endocarditis | Staphylococcus aureus | TVR | No | 1.3 | 78 | 54 | 5 | No | 10 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con22 | 63 | M | 30 | MV and Av endocarditis | Enterococcus faecalis | MV and AVR | No | 9.5 | 138 | 108 | 2 | Yes | 2 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con23 | 41 | M | 20 | MV endocarditis | Streptococcus mitis | MVR | No | 1.7 | 179 | 146 | 1 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con24 | 76 | F | 32 | MV endocarditis | Streptococcus agalctiae | MVR | No | 14.2 | 93 | 66 | 1 | No | 7 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con25 | 82 | M | 21 | AV prothesis endocarditis | Enterococcus faecalis | AVR | No | 13.2 | 182 | 82 | 2 | No | 10 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con26 | 38 | M | 26 | AV endocarditis | none | AVR | No | 2.2 | 73 | 51 | 1 | No | 3 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con27 | 61 | M | 25 | AV prothesis endocarditis | Corynebacterium species | AVR | No | 6.9 | 96 | 53 | 3 | No | 4 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Con28 | 36 | M | 28 | TV endocarditis | Staphylococcus aureus | TVR | Yes | 19.2 | 122 | 58 | 41 | 46 | Yes | 57 | Yes | Yes |

ARR = aortic root replacement; AVR = aortic valve replacement; MVR = mitral valve replacement; ARRec = aortic root reconstruction; TKR = tricuspid valve replacement.

Of note, all sets of data were statistically analyzed and graphically presented by means of the GraphPad Prism 7.01 software showing the median and interquartile range.

Results

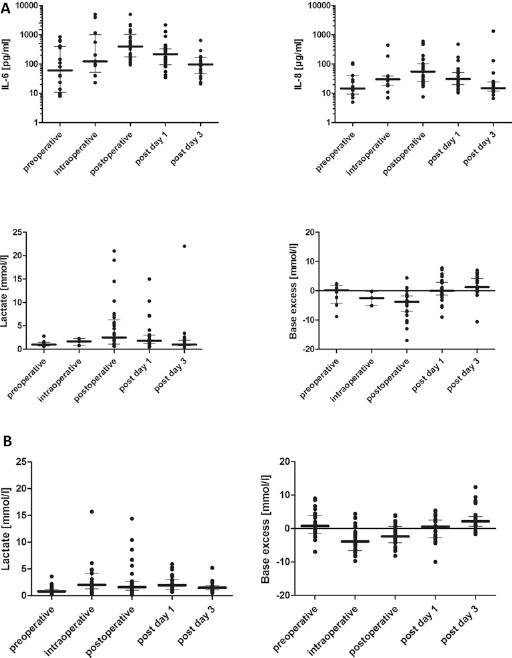

Preoperative EuroSCORE II values in the CytoSorb group were rather heterogeneous, ranging between 2.2 and 96.7 (median 11). In the CytoSorb group, the median EuroSCORE II values for ICU survivors (n = 31) and ICU non-survivors (n = 8) were 11 and 64, respectively. In the comparative historical control group, the median EuroSCORE II values for ICU survivors (n = 26) and ICU non-survivors (n = 2) were 9 and 30, respectively. CPB times and X clamp times are depicted in Table I. All patients in the CytoSorb group obtained CytoSorb treatments that ranged from 64 up to 445 minutes duration (median 132 minutes). All patients showed a marked intraoperative increase of inflammatory mediators IL-6 and IL-8 followed by peak levels measured directly after completion of the surgical procedure. This was followed by a clear decrease in levels of IL-6 and IL-8 on postoperative day 1 and a return to preoperative baseline levels on postoperative day 3 (Fig. 1). Metabolic variables (i.e., lactate and base excess) showed a comparable pattern with a most pronounced change postoperatively and a return to baseline levels on postoperative day 3 (Fig. 1). Corresponding courses of the same metabolic parameters of the comparative historical control group are depicted in Figure 1A. Moreover, we observed a stabilization of hemodynamic parameters, as demonstrated by a consistent and maintained increase in MAP postoperatively with a concomitant reduction of catecholamine need at the same time (epinephrine and norepinephrine) (Fig. 2). On postoperative day 3, 72% and 82% of the patients were free from norepinephrine and epinephrine support, respectively. On postoperative day 5, these percentages increased to 82% and 95% for norepinephrine and epinephrine, respectively (data not shown). Interestingly, 15 out of the 39 IE patients initially requiring vasopressor support in their postoperative phase did not require any further vasopressor support 18 hours post surgery (3 patients with high EuroSCORE II between 31–97; 2 patients with mid EuroSCORE II between 16–31; 10 patients with low EuroSCORE II between 0–16).

Fig. 1.

(A) CytoSorb group: Levels of IL-6 and IL-8 as well as metabolic parameters (lactate and base excess [median with IQR]), throughout the observation period. Values were assessed prior to treatment (baseline), during surgery, immediately after as well as on days 1 and 3 post treatment during CPB. (B) Historical control group: Metabolic parameters (lactate and base excess [median with IQR]), throughout the observation period. Values were assessed prior to treatment (baseline), during surgery, immediately after as well as on day 1 and 3 post CPB.

Fig. 2.

(A) CytoSorb group: Mean arterial pressure (MAP), catecholamine doses (norepinephrine and epinephrine) throughout the observation period (median with IQR). Values were assessed prior to treatment (baseline), at end of surgery, at 6, 12, 18 and 36 hours as well as on day 1, 2 and 3 postoperatively. Please note that data sets were not completed for every patient. (B) Historical control group: Mean arterial pressure (MAP), catecholamine doses (norepinephrine and epinephrine) throughout the observation period (median with IQR). Values were assessed prior to treatment (baseline), at end of surgery, at 6, 12, 18 and 36 hours as well as on day 1, 2 and 3 postoperatively.

The severity of illness in the short-term postoperative period using the APACHE II also showed a trend to improvement from a median of 31 directly post operation to a median of 20 on day 1 post-surgery (Tab. I). A total of 18 patients were able to be weaned from mechanical ventilation within 24 hours after surgery, whereas 21 patients had a prolonged ventilation ranging from 1 to 12 days. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was mandatory in 5 patients for up to 5 days. High grade AKI necessitating CRRT was applied in 16 patients for up to 4 days (Tab. I).

In the comparative historical control group, 12 patients were able to be weaned from mechanical ventilation within 24 hours after surgery, whereas 16 patients had a prolonged ventilation ranging from 2 to 41 days. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was mandatory in 2 patients for up to 8 days. High grade AKI necessitating CRRT was applied in 10 patients for up to 46 days (Tab. II).

Length of ICU stay in the CytoSorb group ranged between 1 and 32 days (median 5). Of the 39 patient treatments summarized in this case series, 8 patients died during their ICU stay (7 between ICU days 1 and 8, 1 patient on ICU day 32) and 2 patients later died during their hospitalization period (Tab. I). Of note, the death of these patients could not be attributed to any specific treatment. One patient died from mesenteric ischemia with no option for surgical treatment, 1 patient had therapy withdrawn in accordance with the patient's advance directive, 5 patients died of refractory multiple organ failure, and 1 patient with refractory cardiac failure.

The length of ICU stay in the comparative historical control group ranged between 2 and 96 days (median 7.5 days). Of the 28 patient evaluated as a historical control group, 2 patients died during ICU stay (days 8 and 96) (Tab. II)

Intraoperative hemoadsorption treatment appeared to be well-tolerated, without device-related adverse events during or after treatment. No technical problems with the implementation of CytoSorb as part of the CPB circuit were observed.

Discussion

This retrospective case series reports on the application of the hemoadsorption cartridge CytoSorb during the intraoperative treatment of 39 patients with IE undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB. The clinical and laboratory parameters measured along this case series revealed (i) a consistent balanced control of the inflammatory response postoperatively, shown by a marked reduction of IL-6 and IL-8 plasma levels, (ii) the rapid adjustment of metabolic processes indicated by a normalization of lactate and base excess back to preoperative baseline levels within 3 days and (iii) hemodynamic stability before, during, and after the operation accompanied by a rapid decrease in need for vasopressors.

As circulating proinflammatory mediators like IL-6 and IL-8 play a central role in the development of SIRS and sepsis, the application of hemoadsorption devices represents a potential interesting interventional tool to avoid detrimental cross-talk between mediators, DAMPS and PAMPS with the immune system. CytoSorb has been shown to effectively remove hydrophobic molecules from 5 kDa up to approximately 55 kDa such as cytokines, chemokines, myoglobin and various other substances (7, 8). Moreover, cytokine reduction by means of CytoSorb application was reported for critically ill and cardiac surgery patients, as supported by a number of published preclinical and clinical data (4, 9, 10). After an initial intraoperative increase of cytokine levels, the application of CytoSorb hemoadsorption in this set of patients was associated with a decrease in the postoperative course. Of note, we are aware of the fact that the standard treatment regimen of these critically ill patients including hydrocortisone and CRRT could also have resulted in an additional decrease of these inflammatory parameters. Despite the exclusively intraoperative use of the cytokine adsorber, a reduction of cytokine levels was observable on postoperative day 1, returning back to preoperative levels on day 3, an effect that could possibly have been supported by the CytoSorb treatment. This long-term effect of even 1 CytoSorb treatment might be explained by the fact that hemoadsorption using CytoSorb might function at the level of the circulating immune effector cells, resulting in decreased activation of NfκB (in neutrophils and Kupffer cells) by a diminished cytokine load in the circulation and a subsequent decrease in cytokine production (11).

In addition, removal of substances is concentration-dependent. While low cytokine plasma concentrations are not affected, high cytokine plasma levels are reduced effectively. Supporting this line of argumentation, a recent blinded, randomized controlled trial in cardiosurgical patients with CPB compared (i) the CytoSorb application during CPB with (ii) a control group without hemoadsorption during CPB (12). Therefore, for instance, the IL-6 level monitored in the plasma of CPB patients did not exceed 254 pg/mL throughout the measurement duration. It is important to note that these were patients (and procedures) with only moderately increased risk who did not suffer from IE at the time of CPB surgery. In contrast, IE patients in our study undergoing CPB had a much more pronounced IL-6 cytokine release level of up to 5,000 pg/mL post treatment. This relevant difference shows that cytokine adsorption might preferably be effective in patients who are in a state of hyperinflammation (e.g., in infective endocarditis). This notion should be even more underlined as Bernardi et al stated that the authors did not find any differences for IL-6 in patients with or without CytoSorb treatment during CPB (12).

The decrease in cytokine levels in our case series was paralleled by a stabilization of hemodynamic parameters, during, and after the operation, as demonstrated by reduced catecholamine support (epinephrine and norepinephrine) and an increase in MAP. This effect has been observed in pre-clinical studies as well as in case report and series (4, 5, 9, 13).

Of note, it should be considered that the historical control group in our study showed a markedly lower risk profile as compared to the CytoSorb group as evidenced by the EuroSCORE II. This important limitation of historical case control analyses needs to be taken into account when comparing outcome data of both groups.

An important point to justify such a preventive treatment approach is the proof of potential outcome benefits despite the additional costs associated with Cytosorb treatment. From our perspective, such treatment might result in a mitigated inflammatory response postoperatively and hence preserve organ function and result in faster recovery during the postoperative course. While systematic data on these cost/benefit questions are still lacking, there is preliminary evidence available on improved organ function after CytoSorb use. Next to descriptions of unexpectedly fast hemodynamic stabilization (5, 14, 15), there is also a recent report indicating (16) a protected vascular barrier function after CytoSorb treatment, which might play an important role in earlier recovery of organ function in systemic hyperinflammation.

Since the question of whether there is a reproducible positive benefit/cost ratio to generally justify preventive CytoSorb treatment in patients with infective endocarditis undergoing cardiac surgery cannot definitely be answered from our case series, it will have to be established in future prospective studies.

Conclusions

With these clinical data and outcomes from 39 patients suffering from IE and undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB in combination with a CytoSorb adsorption device we were able to confirm and extend the results published earlier (5). Treatment with the CytoSorb device was safe and well-tolerated with no device- related adverse events during or after the treatment sessions. Even though clinical experience from this case series looks interesting, it is hard to draw any definite conclusions from this uncontrolled, retrospective, observational trial as to whether the effects seen in these patients were a primary therapy effect of CytoSorb or the consequence of a combination of all conducted treatments. With the insight of this recent case series, randomized controlled trials are warranted to further stress the potential benefits of this new treatment option for IE patients receiving cardiac surgery with CPB.

Disclosures

Conflict of interest: KT and GF received honoraria for lectures from Cytosorbents. KT has an advisory contract with Cytosorbents. The other authors have no conflicts of interest associated with this report.

References

- 1.Carrel T., Englberger L., Takala J.. Whats new in surgical treatment of infective endocarditis? Intensive Care Med. 2016; 42(12): 2052–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2015; 36(44): 3036–3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cremer J., Martin M., Redl H. et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996; 61(6): 1714–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Born F., Pichlmaier M., Peterß S. et al. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome in in Heart Surgery: New possibilities for treatment through the use of a cytokine adsorber during ECC? Kardiotechnik. 2014; 2: 1–10 http://armaghansalamat.com/media/brands/Cytosorbents/Literature/2014_Born%20F%20et%20al.,%20Systemic%20lnflammatory%20Response%20Syndrome%20in%20der%20Herzchirurgie_Kardiotechnik%2002-2014%20-%20English%20Translation.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Träger K., Fritzler D., Fischer G. et al. Treatment of post-cardiopulmonary bypass SIRS by hemoadsorption: a case series. Int J Artif Organs. 2016; 39(3): 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nashef S.A., Roques F., Sharpies L.D. et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012; 41(4): 734–744, discussion 744–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellum J.A., Song M., Venkataraman R.. Hemoadsorption removes tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10, reduces nuclear factor-kappaB DNA binding, and improves short-term survival in lethal endotoxemia. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32(3): 801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuntsevich V.I., Feinfeld D.A., Audia P.F. et al. In-vitro myoglobin clearance by a novel sorbent system. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2009; 37(1): 45–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hetz H., Berger R., Recknagel P., Steltzer H.. Septic shock secondary to β-hemolytic streptococcus-induced necrotizing fasciitis treated with a novel cytokine adsorption therapy. Int J Artif Organs. 2014; 37(5): 422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schädler D., Porzelius C., Jörres A. et al. A multicenter randomized controlled study of an extracorporeal cytokine hemoadsorption device in septic patients. Crit Care. 2013; 17(Suppl 2): 62. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng Z.Y., Wang H.Z., Carter M.J. et al. Acute removal of common sepsis mediators does not explain the effects of extracorporeal blood purification in experimental sepsis. Kidney Int. 2012; 81(4): 363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardi M.H., Rinoesl H., Dragosits K. et al. Effect of hemoadsorption during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery - a blinded, randomized, controlled pilot study using a novel adsorbent. Crit Care. 2016; 20: 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng Z.Y., Carter M.J., Kellum J.A.. Effects of hemoadsorption on cytokine removal and short-term survival in septic rats. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36(5): 1573–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kogelmann K., Druener M., Jarczak D.. Observations in early vs. late use of CytoSorb® haemadsorption therapy in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2016; 20(Suppl 2): 195.27334713 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lees N.J., Rosenberg A., Hurtado-Doce Al et al. Combination of ECMO and cytokine adsorption therapy for severe sepsis with cardiogenic shock and ARDS due to Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia and H1N1. J Artif Organs. 2016; 19(4): 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David S., Thamm K., Schmidt B.M., Falk C.S., Kielstein J.T.. Effect of extracorporeal cytokine removal on vascular barrier function in a septic shock patient. J Intensive Care. 2017; 5: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]