Abstract

Background:

Recent trials suggest fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) with repeated enemas and high diversity FMT donors is a promising treatment to induce remission in ulcerative colitis (UC).

Methods:

We designed a prospective, open-label pilot study to assess the safety, clinical efficacy, and microbial engraftment of single FMT delivery by colonoscopy for active UC using a two donor fecal microbiota preparation (FMP). Safety and clinical endpoints of response, remission, and mucosal healing at week 4 were assessed. Fecal DNA and rectal biopsies were used to characterize the microbiome and mucosal CD4+ T cells, respectively, before and after FMT.

Results:

Seven patients (35%) achieved a clinical response by week 4. Three patients (15%) were in remission at week 4 and two of these patients (10%) achieved mucosal healing. Three patients (15%) required escalation of care. No serious adverse events were observed. Microbiome analysis revealed that restricted diversity of recipients pre-FMT was significantly increased by high diversity two donor FMP. The microbiome of recipients post-transplant was more similar to the donor FMP than the pre-transplant recipient sample in both responders and non-responders. Notably, donor composition correlated with clinical response. Mucosal CD4+ T cell analysis revealed a reduction in both Th1 and regulatory T cells post-FMT.

Conclusions:

High-diversity, two donor FMP delivery by colonoscopy is safe and effective in increasing fecal microbial diversity in patients with active UC. Donor composition correlated with clinical response and further characterization of immunological parameters may provide insight into factors influencing clinical outcome.

Keywords: Microbiome, Fecal Microbiota Transplantation, Ulcerative Colitis

Introduction

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has emerged as an effective therapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), and increased microbial diversity is a characteristic feature of a successful responder (1); however, the efficacy of FMT for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) remains unclear. Although the etiopathogenesis of IBD is thought to be multifactorial, alterations in the intestinal microbiome are characteristic of both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC)(2). Given that extensive characterization in animal models supports a role for the microbiome in driving aberrant inflammatory disease in a genetically susceptible host, several studies have recently sought to evaluate the role for FMT in the treatment of IBD.

Two randomized controlled trials of FMT for treatment of active UC were recently reported with mixed clinical efficacy (3, 4). The TURN trial (N=50) which delivered FMT via nasoduodenal tube at week 0 and week 3 showed no significant change in clinical remission between subjects who received donor or autologous stool (3). In contrast, a 6-weekly fecal enema based FMT study (N=75) showed significant improvement in clinical remission (4). Despite differences in primary clinical endpoints, both studies showed effective engraftment of a donor microbiota with increased diversity. Although differences between responders and non-responders did not meet significance for UC, analysis of donor characteristics revealed a “superdonor” that was responsible for treatment success suggesting the importance of donor composition (4). Differences in patient population, dosing regimen, and delivery modalities may also account for discordant results between these studies. Repeated delivery of fecal enema may provide more effective delivery than nasoduodenal delivery or single colonoscopic delivery, which was not clinically effective in smaller studies (5). The rational utilization of engraftment metrics, donor composition, and delivery modality remain critical outstanding questions in FMT design.

To help address these questions, we performed a single-center, prospective, open-label pilot study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of two donor fecal microbiota preparation (FMP) delivery by colonoscopy. By combining donors for the FMP, this strategy allowed us to evaluate both increased diversity of the FMP and donor characteristics in relation to clinical response. Immune cell profiling was performed on mucosal biopsies before and after FMT to assess the impact on mucosal T cell immunity.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02516384). Eligible patients required biopsy-proven UC with active disease as defined by Mayo score ≥ 3 and an endoscopic subscore ≥1. Potential FMT patients underwent interview and physical examination to determine eligibility. Criteria for inclusion were age ≥18 year old at the time of enrollment and willingness to undergo screening for blood-borne and stool-borne pathogens as recommended by the FDA. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: biopsy-proven Crohn’s disease or indeterminate colitis, acute abdomen or other clinical emergencies requiring emergent management, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), pregnancy, concurrent CDI or other infection, prior history of FMT, antibiotic use within the prior 3 months, other causes of diarrhea, including but not limited to tube feeds and medications (i.e., kayaxelate, metformin, lactulose, laxatives, magnesium), major congenital defects, recent malignancy in the last 5 years excluding non-melanoma skin cancers, anaphylactic reaction to food, or any other condition that in the investigators’ opinion would jeopardize the safety or rights of the participant, would make it unlikely for the participant to complete the study, or would confound the study results.

Eligible patients underwent serological testing for HIV type 1 and 2 antibody (Ab), Hepatitis A total Ab, Hepatitis B surface antigen (Ag), Hepatitis B surface Ab, Hepatitis B core Ab (IgM and IgG), Hepatitis C Ab, CMV IgM and RPR. They also underwent stool testing with bacterial culture for enteric pathogens (E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter), ova and parasites; Clostridium difficile toxin by PCR; fecal Giardia, Cryptosporidium and H. pylori antigen; and Norovirus and Rotavirus via EIA. Females of childbearing potential had a urine pregnancy test on the day of the FMT procedure to ensure eligibility, as well as serum beta-HCG testing at each follow-up visit.

Donor Fecal Microbiota Preparation

Two donor fecal microbiota preparations (FMP) were provided from rigorously screened healthy donors from a universal stool bank (OpenBiome) (6). 60 ml of material from each of two donors was thawed, pooled, and homogenized immediately prior to colonoscopic delivery to the ileum and right colon. Donor combinations were selected using a four choose two factorial design with all pairwise combinations of four donors evaluated at least three times.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

All patients meeting entry criteria underwent standard polyethylene glycol-based colonoscopy bowel preparation and magnesium citrate on the day prior to colonoscopy. No antibiotic pre-treatment was administered before FMT. Colonoscopy was performed to the terminal ileum. FMP was delivered in the terminal ileum and right colon in equal proportions. Prior to administration, two mucosal biopsies were obtained from the rectum for cellular analysis. Following colonoscopy, patients were administered 4mg of loperamide to assist with FMT retention.

Outcome measures

Patients were followed post-FMT by medical interview and physical exam at 2, 4 and 12 weeks. At each visit, patients underwent medical interview and physical examination to assess for UC activity via partial Mayo score as well as adverse reactions. Additionally, patients received follow-up phone calls post-FMT at 24 hours, 1 week, and 6 weeks. Patients were instructed to notify the treating physician at any time post-FMT if they were to develop any infectious symptoms or new medical conditions. At week 2 and 4 post-FMT, stool samples for stool studies were collected. At week 4 post-FMT, flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed along with mucosal biopsies of rectal mucosa for cellular analysis. The primary endpoint outcome of safety was evaluated by adverse events assessment within 24 hours of FMT and then weekly until week 6. Adverse event severity and relatedness was graded using NIH criteria. Secondary outcomes included clinical response (ΔMayo score ≥ 3 and a bleeding subscore ≤1), clinical remission (Mayo score ≤2 and no subscore >1), and progression of disease (measured by initiation of anti-TNFα, escalation of dosage, or colectomy).

Lamina Propria Cell Isolation and Flow cytometry.

Lamina propria mononuclear cells were isolated from colonic tissue as previously described (7). LIVE/DEAD fixable aqua dead cell stain kit (Molecular Probes) was used to exclude dead cells. For cytokine detection, cells were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin with BD GolgiPlug for 4 hours. Following surface-marker staining with anti-CD3-APCCy7 (eBiosciences UCHT1) and anti-CD4-BUV650 (BioLegend OKT4), cells were prepared as per manufacturer’s instruction with Cytoperm/Cytofix (BD Biosciences) for intracellular cytokine evaluation of IL-17A (eBiosciences eBio64DEC17), IL-4 (eBiosciences 8D4-8), IL-22 (eBiosciences 22URTI) and IFNγ (eBiosciences 4S.B3). For transcription factor analysis, cells were fixed and permeabilized as per manufacturer’s instructions (eBiosciences) and stained intracellularly with anti-Foxp3-E450 (eBiosciences 236A/E7) and anti-RORγt-PE (eBiosciences AFKJS-9). Data acquisition was computed with BD LSRFortessa flow cytometers and analysis performed with FlowJo software.

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Analyses.

16S rRNA gene sequencing methods were adapted from the methods developed for the NIH-Human Microbiome Project (8). Briefly, bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using MO BIO PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories). The 16S rDNA V4 region was amplified by PCR and sequenced in the MiSeq platform (Illumina) using the 2×250 bp paired-end protocol (9). The 16S rRNA gene pipeline incorporates phylogenetic and alignment-based approaches to maximize data resolution (10). The read pairs were demultiplexed based on the unique molecular barcodes, and reads were merged using USEARCH v7.0.1090 (11), allowing zero mismatches and a minimum overlap of 50 bases. Merged reads were trimmed at the first base with Q5. In addition, a quality filter was applied to the resulting merged reads and reads with > 0.05 expected errors were discarded. 16S rRNA gene sequences were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at a similarity cutoff value of 97% using the UPARSE algorithm. OTUs were mapped to an optimized version of the SILVA Database (12, 13) containing only the 16S V4 region to determine taxonomies. Abundances were recovered by mapping the demultiplexed reads to the UPARSE OTUs. A rarefied OTU table (>8000 reads / sample) from the output files generated in the previous two steps was used for downstream analyses of α-diversity, β-diversity (14), and phylogenetic trends.

Results

Two donor FMP is safe and effective in active UC

To increase the microbial diversity of the donor material, we prepared two donor FMP. Simulation models of single donor sequence data (validated on sequence data from large 48-donor pools) reliably show that multiple donor FMP has higher diversity than single donor FMP (Fig. S1). Increasing pool size, however, simultaneously decreases donor heterogeneity (Fig. S2). Therefore, to maintain FMP heterogeneity and the possibility to detect differential donor effects, two donor FMP was used in this study.

Baseline clinical characteristics for all 20 subjects are presented in Table 1. All 20 enrolled patients successfully completed the trial through week 4. Although no serious adverse events were observed, minor grade 1 adverse events were recorded, all of which were deemed to be “possibly related” to FMT (Table S1). One patient had a transient febrile response, which improved with conservative care within 5 days. Three patients required escalation of care following week 4 post-FMT. Two of these three patients had an increase in their week 4 Mayo score and were treated with either anti-TNFα blockade therapy or colectomy. The third patient had a clinical response per study definition, but opted for anti-TNFα blockade therapy with a post-FMT Mayo score of 7. Consistent with previous studies using single donor FMP, two donor FMP was well tolerated in the setting of active UC.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of recipients prior to FMT.

| Baseline Characteristics | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean, SD) | 38.4 (12.6) | 23 - 71 |

| Sex (N, %) | ||

| Male | 12 (60.0%) | |

| Female | 8 (40.0%) | |

| Extent of disease (N, %) | ||

| Proctitis | 1 (5.0%) | |

| Proctosigmoiditis | 3 (15.0%) | |

| Left sided colitis | 7 (35.0%) | |

| Pancolitis | 9 (45.0%) | |

| UC Medications | ||

| Corticosteroids | 6 (30.0%) | |

| Mesalamine | 11 (55.5%) | |

| Anti-TNFα | 1 (5.0%) | |

| Vedolizumab | 3 (15.0%) | |

| None | 4 (20.0%) | |

| Labs (Mean, SD) | ||

| WBC (× 103 / mL) | 7.4 (1.9) | 4.4 - 10.4 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.1 (1.3) | 10.3 - 15.2 |

| ESR | 22.6 (19.8) | 4.0 - 72.0 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.9 (1.5) | 0.0 - 6.8 |

| Scores (Mean, SD) | ||

| Pre-FMT total Mayo score | 8.1 (2.4) | 3.0-11.0 |

| Pre-FMT endoscopic Mayo score | 2.4 (0.8) | 1.0-3.0 |

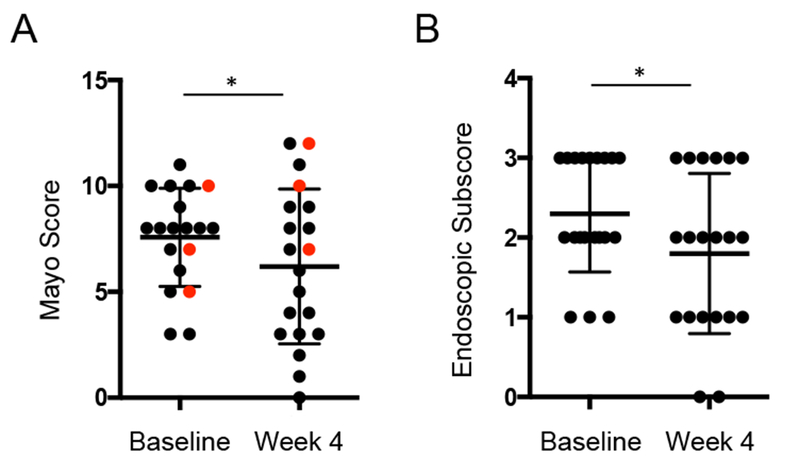

Seven patients (35%) achieved a clinical response (ΔMayo score ≥ 3 and a bleeding subscore ≤1) by week 4. Three patients (15%) were in clinical remission at week 4 (Mayo score ≤2 and no subscore >1), and two of these patients (10%) achieved mucosal healing (endoscopy subscore of 0). Paired analysis showed a significant improvement in endoscopic subscore (Median decrease of 1.0, p = 0.01) (Fig. 1A) for all patients and Mayo score (Median decrease of 1.5, p = 0.02) (Fig. 1B) for the patients not requiring escalation of care. No significant differences in ESR or CRP were seen post-FMT.

Figure 1. Two donor FMP improved Mayo score and endoscopic subscore at week 4 post-FMT.

A. Complete Mayo score at baseline and 4 weeks post-FMT. Red dots indicate subjects requiring escalation of care. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test of subjects not requiring escalation of care is indicated by asterisk. B. Endoscopic subscore score at baseline and 4 weeks post-FMT. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, p-value < 0.05 is indicated.

Two donor FMP effectively engrafts in both responders and non-responders

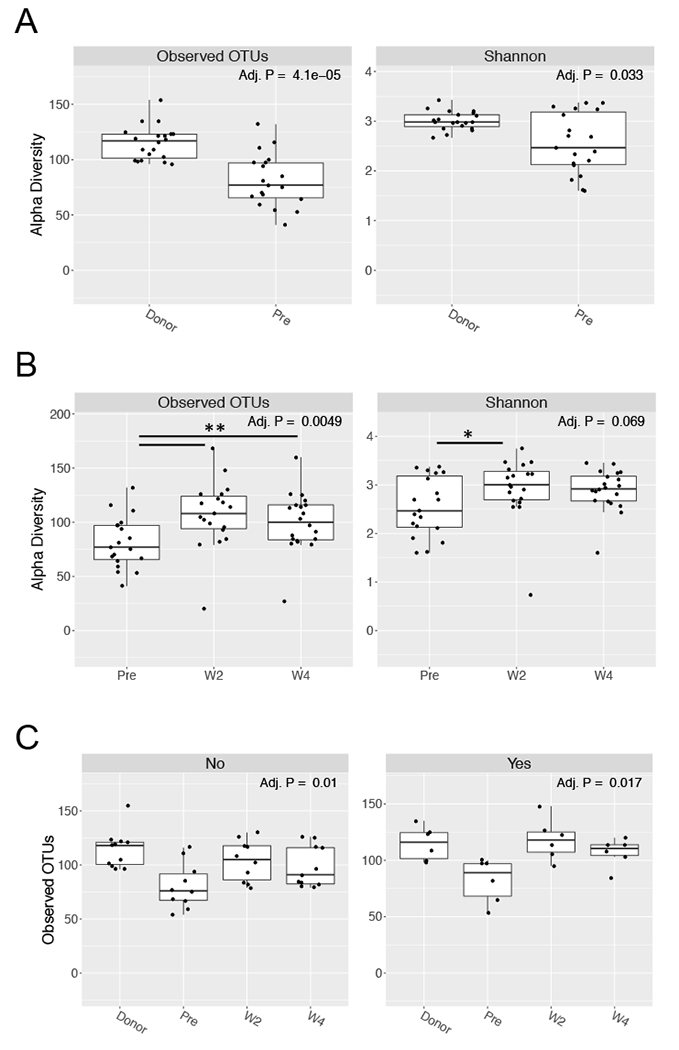

To evaluate the impact of two donor FMP on microbial diversity, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed on recipient fecal DNA samples pre- and 2 and 4 weeks post- transplant. Analysis of species-level alpha diversity in pre-transplant recipients revealed significantly fewer observed OTUs (p=4.1 × 10−5) and a lower Shannon diversity index (p=0.03) compared to the two donor FMP (Fig. 2A). Compared to recipient sample pre-transplant, two donor FMP significantly enhanced OTU diversity at both 2 and 4 weeks post-FMT and Shannon diversity at 2 weeks post-FMT (Fig. 2B). This effect of two donor FMP was seen in both clinical responders and non-responders (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Two donor FMP increases recipient diversity.

Fecal DNA samples were sequenced by 16S rRNA sequencing. A. Alpha diversity metrics of observed OTUs (left panel) and Shannon index (right panel) are compared for donor and recipient pre-transplant (pre). B. Alpha diversity metrics of observed OTUs (left panel) and Shannon index (right panel) are compared for recipient pre-transplant (pre) and at week 2 (W2) and 4 (W4) following FMT. C. Alpha diversity of samples faceted by the primary endpoint of clinical response (No, left panel; Yes, right panel). For all panels P-values are shown, Kruskal-Wallis.

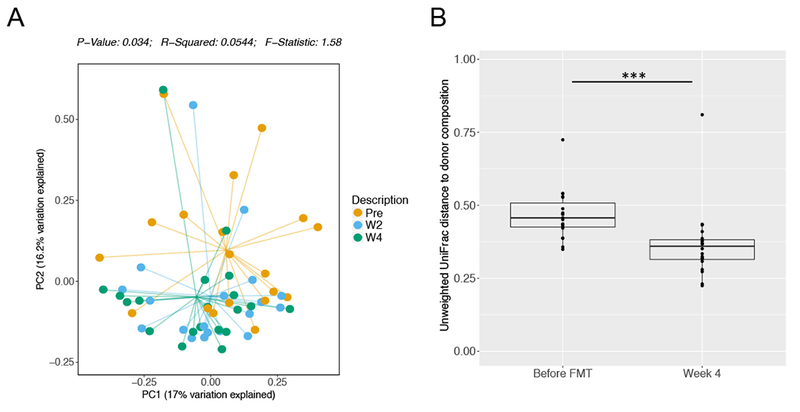

To evaluate engraftment as a function of microbial composition, we analyzed recipient beta diversity pre- and post-transplant. Principal coordinate analysis of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix revealed significant differences in the recipient pre-transplant compared with 2 and 4 weeks post-transplant (p<0.034) (Fig. 3A, S3A). Similarly, week 4 recipient samples were more similar to donor FMP than pre-transplant recipient samples by unweighted UniFrac (Fig. 3B) and Jensen-Shannon (Fig. S3B) distance. These data suggest that a single colonoscopic delivery of two donor FMP is safe and effective in increasing microbial diversity in patients with active UC.

Figure 3. Two donor FMP engrafts effectively in active UC recipient.

A. Principal coordinate analysis plot is shown using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix and stratified by recipient pre-transplant (pre, orange) and at week 2 (W2, blue) and 4 (W4, green) following FMT. P-values are shown, Monte-Carlo, PERMANOVA. B. Unweighted UniFrac distance to donor is shown for the recipient before FMT and at 4 weeks post-FMT. P-values are indicated, Wilcoxon signed rank.

Donor composition correlates with clinical response

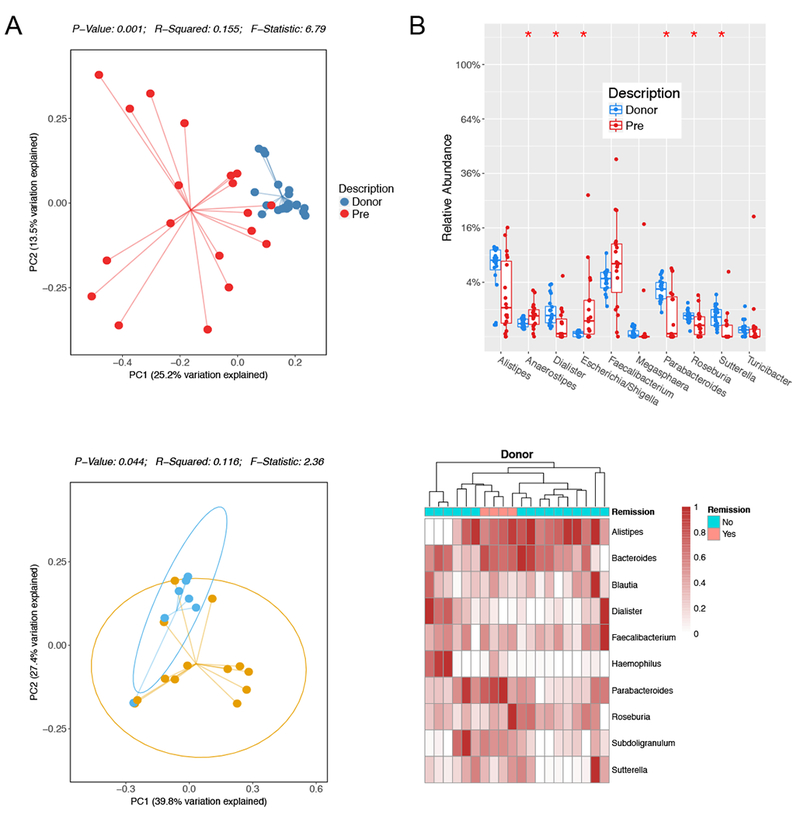

In addition to the significantly enhanced diversity of two donor FMP, principal coordinate analysis of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix revealed significant differences between two donor FMP and pre-transplant recipients (Fig. 4A). At the genus level, two donor FMP had higher levels of Dialister, Parabacteroides, Roseburia, and Sutterella while recipients had higher levels of Anaerostipes and Escherichia/Shigella (Fig. 4B). Given these taxonomic differences between donor and recipient, we next evaluated donor microbial composition according to clinical response at week 4. Principal coordinate analysis of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix revealed significant separation between donor samples achieving clinical response and those not (Fig. 4C). Although specific genus-level differences alone did not significantly differentiate these donor samples, donors achieving clinical remission clustered together on taxonomic alignment (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these data show that, despite characteristic differences in donor FMP with active UC, donor heterogeneity correlates with clinical outcome.

Figure 4. Donor composition correlates with clinical response.

A. Principal coordinate analysis plot is shown using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix and stratified by donor (blue) and recipient pre-transplant (pre, red). P-values are shown, Monte-Carlo, PERMANOVA. B. Boxplot displays the top 10 differential abundant bacteria by genus between donor and recipient pre-transplant (Pre). P-values indicated by *<0.05, Mann-Whitney, FDR-adjusted. C. Principal coordinate analysis of donor composition by Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix stratified by clinical response. P-values indicated, Monte Carlo, PERMANOVA. D. Hierarchical clustering of a heatmap representation of donor composition by genus colored by clinical remission as indicated. Scale represents the normalized relative abundance.

Two donor FMP alters mucosal T cell responses

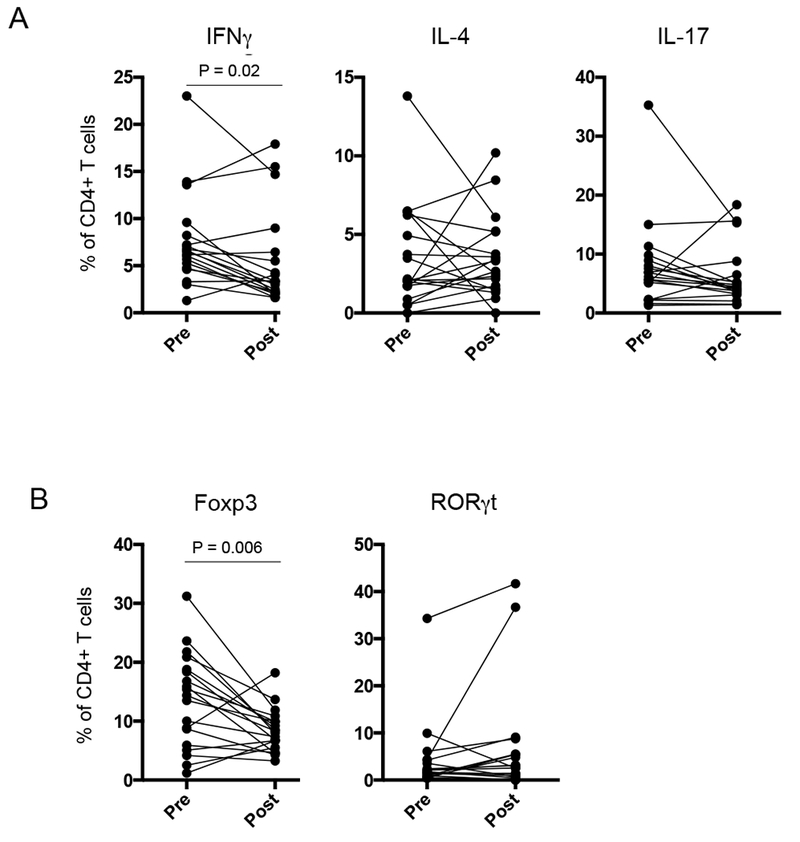

Alterations in the composition of the intestinal microbiome have been shown to impact mucosal T cell effector function in mouse models (15, 16). To evaluate the impact of two donor FMP on mucosal immunity in active UC, we profiled mucosal CD4+ T cell function in rectal biopsies performed at the time of FMT and 4 weeks post-FMT (Fig. S4). Analysis of CD4+ T cell cytokine production revealed a significant reduction in IFNγ production at 4 weeks post- FMT (p=0.02) (Fig. 4A). No difference in IL-4, IL-17, or IL-22 was seen. Intranuclear staining of transcription factors Foxp3 or RORγt was performed to identify regulatory T cells (Treg) or T helper cells that produce IL-17 (Th17). Our results revealed a significant reduction in Tregs at week 4 compared to time of transplant (p=0.006), but no difference in mucosal Th17 cells was seen (Fig. 4B). These data reveal the ability of two donor FMP to impact mucosal CD4+ T cell effector function.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the clinical, microbiological, and immunological impact of two donor FMP in FMT for active UC. Although this study was not placebo-controlled, clinical response (35%) and remission rates (20%) were similar to a recently reported placebo-controlled trial (39% response and 24% remission at week 7) (4). Furthermore, FMT with two donor FMP was well tolerated, and the frequency of grade 1 adverse events was consistent with the expected incidence in both the treatment and controls reported previously (3, 4). These data, coupled with the significant decrease in week 4 Mayo score and endoscopic subscore, suggest that the two donor FMP is safe and effective. Similar to repeat enema delivery, these data support the short-term efficacy of single colonic delivery in UC, but longer follow up will be needed to assess the durability of engraftment.

Given the restricted microbial diversity of a UC recipient with active disease, diversity and donor engraftment have been used as a metrics of clinical efficacy. Increase in microbial diversity correlates with response in recurrent C. difficile-associated diarrhea (1), while pilot studies in Crohn’s disease (17) showed an increase in both diversity and donor engraftment, which correlated with clinical response. Although both duodenal and colonic delivery FMT studies have shown efficacy in both of these parameters post-FMT, the correlation of diversity and engraftment with clinical response was modest (3, 4). In contrast to these studies (3), the use of two donor FMP provided us with a donor material with significantly higher microbial diversity than pre-FMT recipients. Our results reveal a robust increase in both diversity and engraftment in all patients that did not require escalation of care and these metrics reflect an overall improvement in clinical Mayo score.

Alternatively, donor microbial characteristics, rather than metrics of diversity and engraftment, may be critical in understanding clinical efficacy. Most notably, the positive clinical results shown by Moayyedi et al are primarily driven by the success of FMT with “superdonor B”. Consistent with these results, our two donor composition strategy afforded us significant heterogeneity to reveal similarity in donors that achieved clinical response. Although no specific OTU was identified, donor microbiota inducing clinical remission showed strong signatures of Parabacteroides, which has been shown to attenuate colitis in mice (18).

The ability of FMT to impact the mucosal immune response remains a critical question. Although Crohn’s disease was initially characterized as a Th1- and UC as a Th2-driven inflammatory disease, additional T cell subsets have been identified to play a role in IBD mucosal barrier immunity including regulatory T cells and IL-23 responsive Th17 cells (15). In mouse models, human microbiota have been shown to play a critical role in regulating Th1 (19), regulatory T cells (20), and Th17 (16, 21). Immune cell analyses in FMT studies have been limited, but a recent analysis in Crohn’s disease revealed a borderline increase in CD25+ CD127lo CD4+ T cells at 12 weeks post-FMT (17). The reduction of Th1 and concomitant decrease in regulatory T cells that we report may reflect an acute reduction in inflammation consistent with the overall reduction in endoscopic subscore. Longer follow up is needed to evaluate long-lasting effects such as regulatory T cell expansion.

FMT has exciting potential as therapy for UC. Our study supports the safety and efficacy of single colonoscopic delivery of a high diversity, two donor FMP. Larger, placebo-controlled trials are needed to evaluate this strategy. This study provides proof-of-principle that two donor combinations can help to identify donor microbiota that drive clinical efficacy. Coupled with immune cell profiling, these approaches may help identify critical, transferable, immune-reactive probiotics that may serve as the backbone for FMT in UC.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Adverse events reported post-FMT

Figure S1. Larger donor pools increase within-FMP diversity

Figure S2. Smaller pools preserve FMP heterogeneity

Figure S3. Recipient microbiota 4 weeks post-FMT is more similar to donor

Figure S4. Gating strategy for mucosal CD4+ T cells

Figure 5. Two donor FMP alters mucosal T cell responses.

Lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) were isolated from rectal endoscopic biopsies taken before (Pre) and 4 weeks after FMT (Post). A. LPMCs were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 4 hours and intracellular cytokine staining was performed. The percentage of total CD4+ T cells producing the designated cytokine is indicated. P-values reflect paired T-test. B. LPMCs were stained for Foxp3 and RORγt expression. The percentage of total CD4+ T cells expressing the designated transcription factor is indicated. P-values reflect paired T-test.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes at week 4 post-FMT.

| Outcome | Week 4 Post-FMT |

|---|---|

| Clinical Response | 7 (35.0%) |

| Clinical Remission | 3 (15.0%) |

| Mucosal Healing | 2 (10.0%) |

| Escalation of Therapy | 3 (15.0%) |

| Colectomy | 1 (5.0%) |

| Medical | 2 (10.0%) |

Acknowledgements:

We would like recognize the patients for their participation in this study and the clinical research team of the Jill Roberts Center. We thank Dr. Linnie Golytely for her input and supervision. VJ, CC, and RSL thank the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in IBD and the Center for Advanced Digestive Care for their generous support. ZK and MS thank the Neil & Anna Rasmussen Foundation and Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation for support of OpenBiome, a non-profit universal stool bank.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from Center for Advanced Digestive Care / Roberts Institute for Research in IBD (V.J., C.C, R.S.L).

References:

- 1.van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:577–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, et al. Findings From a Randomized Controlled Trial of Fecal Transplantation for Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:110–118 e114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moayyedi P, Surette MG, Kim PT, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Induces Remission in Patients With Active Ulcerative Colitis in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:102–109 e106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kump PK, Grochenig HP, Lackner S, et al. Alteration of intestinal dysbiosis by fecal microbiota transplantation does not induce remission in patients with chronic active ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2155–2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ling B Kelly, Koelsch Emily, RN BSN, Dubois Nancy, MSN MBA, O’brien Kelsey, MPH, Stoltzner Zachery, BS, Panchal Pratik, MD, MPH, Amaratunga Kanchana, MD MPH, Kassam Zain, MD MPH and Osman Majdi, MD MPH Prospective Laboratory Evaluation of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Donors: Results from an International Public Stool Bank. ID Week. New Orleans, LA; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diehl GE, Longman RS, Zhang JX, et al. Microbiota restricts trafficking of bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes by CX(3)CR1(hi) cells. Nature. 2013;494:116–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Human Microbiome Project C. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. Isme J. 2012;6:1621–1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buffington SA, Di Prisco GV, Auchtung TA, et al. Microbial Reconstitution Reverses Maternal Diet-Induced Social and Synaptic Deficits in Offspring. Cell. 2016;165:1762–1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10:996–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8228–8235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longman RS, Yang Y, Diehl GE, et al. Microbiota: host interactions in mucosal homeostasis and systemic autoimmunity. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2013;78:193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viladomiu M, Kivolowitz C, Abdulhamid A, Dogan B, Victorio D, Castellanos JG, Woo V, Teng F, Tran NL, Sczesnak A, Chai C, Diehl GE, Ajami N, Petrosino J, Zhou XK, Schwartzman S, Mandl L, Abramowitz M, Jacob V, Bosworth B, Steinlauf A, Scherl EJ, Wu HJ, Simpson KW, Longman RS IgA-coated E. coli enriched in Crohn’s Disease Spondyloarthritis Promote Th17-dependent Inflammation. Sci Transl Med. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaughn BP, Vatanen T, Allegretti JR, et al. Increased Intestinal Microbial Diversity Following Fecal Microbiota Transplant for Active Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2182–2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kverka M, Zakostelska Z, Klimesova K, et al. Oral administration of Parabacteroides distasonis antigens attenuates experimental murine colitis through modulation of immunity and microbiota composition. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;163:250–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, et al. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. 2005;122:107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500:232–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan TG, Sefik E, Geva-Zatorsky N, et al. Identifying species of symbiont bacteria from the human gut that, alone, can induce intestinal Th17 cells in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Adverse events reported post-FMT

Figure S1. Larger donor pools increase within-FMP diversity

Figure S2. Smaller pools preserve FMP heterogeneity

Figure S3. Recipient microbiota 4 weeks post-FMT is more similar to donor

Figure S4. Gating strategy for mucosal CD4+ T cells