Abstract

Fibrosis following injury leads to aberrant regeneration and incomplete functional recovery of skeletal muscle, but the lack of detailed knowledge about the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved hampers the design of effective treatments. Using state-of-the-art technologies, Murray et al. (2017) found that perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells generate fibrotic cells in the skeletal muscle. Strikingly, genetic deletion of αv integrins from perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells significantly inhibited skeletal muscle fibrosis without affecting muscle vascularization or regeneration. In addition, the authors showed that a small molecule inhibitor of αv integrins, CWHM 12, attenuates skeletal muscle fibrosis. From a drug-development perspective, this study identifies a new cellular and molecular target to treat skeletal muscle fibrosis.

Keywords: perivascular cells, skeletal muscle, fibrosis, integrins, PDGFRβ

Deposition of connective tissue is beneficial for repair in the short-term (Eming et al., 2014). However, over a prolonged period, fibrosis, characterized by excessive deposition of extracellular matrix constituents, becomes detrimental (O’Reilly, 2017). Associated with most chronic diseases and postnatal healing processes, it is an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, responsible for approximately 45 percent of mortality in the United States (Thannickal et al., 2014), (Gurtner et al., 2008). It may be triggered in response to various insults, including chronic inflammation, tissue injury, and autoimmune reactions. It occurs in a wide range of organs and may affect their architecture, becoming irreversible over time, and leading to organ failure (Affo et al., 2017; Birbrair et al., 2014a; Birbrair et al., 2013d; Martinez et al., 2017; Munoz-Felix et al., 2015; Nishiga et al., 2017; Rockey et al., 2015). Although reducing fibrosis would probably protect organs, treatment options are very limited.

The pathophysiological etiology of fibrosis in skeletal muscle is less understood than in other organs (Birbrair et al., 2014b). Fibrosis interferes with skeletal muscle regeneration (Huard et al., 2002); alters the skeletal muscle microenvironment to increase susceptibility to re-injury (Birbrair, 2017; Carlson, 1986; Huard et al., 2002; Mu et al., 2010); and impairs function (Lieber and Ward, 2013). It causes devastating clinical problems; for example, when retracted rotator cuff skeletal muscles separate from the bone (Zumstein et al., 2008) or contractures permanently fix joints in a position that requires surgical relief (Lieber and Friden, 2002). Fibrosis is characterized by mechanical stiffness of muscle fiber bundles and increased collagen accumulation. Understanding the origin and processes that drive fibrous tissue formation is a central question in skeletal muscle biology.

Myofibroblasts regulate tissue fibrosis by producing several extracellular matrix proteins (Wynn, 2008). Understanding which cells generate them may allow us to gain control of or even reverse fibrosis in pathologic conditions (Friedman et al., 2013), and recent studies in various organs have focused on them to accelerate the design of targeted anti-fibrotic treatments. So far, many cell populations have been implicated, including circulating progenitor cells (Scholten et al., 2011), endothelial cells (Zeisberg et al., 2007), resident fibroblasts (Barnes and Glass, 2011), epithelial cells (Kim, K.K. et al., 2006), and pericytes (Birbrair et al., 2015). The contribution of each cell type varies among organs (LeBleu et al., 2013). Other studies have elucidated the cellular complexity of the skeletal muscle microenvironment (Birbrair et al., 2014b). Nonetheless, the particular cells and underlying cellular and molecular processes directly responsible for skeletal muscle fibrosis remain unknown.

Studies in several organs have pointed to the plasticity of perivascular cells, which allows them to differentiate into other cell types (Birbrair et al., 2017b; Birbrair et al., 2017c), including extracellular matrix-forming cells (Birbrair et al., 2014a; Birbrair et al., 2013d, 2014b, 2015). Murray and colleagues’ recent article in Nature Communications identifies αv integrins on perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells as a therapeutic target for skeletal muscle fibrosis (Murray et al., 2017). They used state-of-the-art techniques, including in vivo lineage-tracing, confocal microscopy, sophisticated Cre/loxP technologies, and in vivo pharmacological blockade, to determine the role of these cells in skeletal muscle fibrosis formation. PDGFRβ-expressing cells are perivascular and located in close proximity to CD31+ muscular endothelial cells. Using PDGFRβ-Cre/mTmG mice, the authors labeled both quiescent PDGFRβ+ cells and activated myofibroblasts and found that the perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells originated fibrotic cells in the skeletal muscle (Murray et al., 2017). Strikingly, genetic deletion of αv integrins specifically from the perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells significantly inhibited skeletal muscle fibrosis without affecting muscle vascularization or regeneration. The authors also showed that a small molecule inhibitor of αv integrins, CWHM 12, attenuates skeletal muscle fibrosis even when administered after fibrosis is established. Moreover, αv integrins are expressed and targetable in PDGFRβ-expressing cells from human skeletal muscle (Murray et al., 2017). This study will inform direly needed new clinical therapies.

Below, we discuss this work’s findings in the context of recent advances in our understanding of the role of perivascular cells in the skeletal muscle microenvironment and fibrosis generation.

PERSPECTIVES / FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The molecular functions of specific genes seem to depend on the cellular population that expresses them. Restricting gene manipulation to specific cells in the skeletal muscle has clarified the role of key proteins in physiological and pathological states and offers a very powerful tool. The main findings from the Murray study are based on data obtained using PDGFRβ-Cre/αv integrin-floxed mice (Murray et al., 2017). Although the authors show that these cells are perivascular in the skeletal muscle, their identity remains unknown. PDGFRβ is expressed in many cellular lineages throughout the embryo during development, so PDGFRβ-Cre transgenic mice are not the best model for lineage tracing; many cell populations are probably being labeled at the same time (Birbrair et al., 2017a; Guimaraes-Camboa et al., 2017). Since PDGFRβ expression is more restricted in adult animals, using PDGFRβ-CreERT2 mice would be more suitable (Gerl et al., 2015). This model would allow genetic elimination of the αv integrins even after the fibrotic disease is established and define the role of αv integrins on perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells during muscular fibrosis.

In addition, PDGFRβ expression, even in adult animals, is not restricted to a single perivascular cell type. Several stromal cells, such as pericytes (Birbrair et al., 2013c; Costa et al., 2018), vascular smooth muscle cells (Lindahl et al., 1997; Winkler et al., 2010), and fibroblasts (Ohlund et al., 2017) express this cell-surface tyrosine kinase receptor (Armulik et al., 2011). The contribution of these distinct cell populations to fibrous tissue deposition in the skeletal muscle remains unknown. The problem’s complexity is increased by the fact that subpopulations of these cell subsets with distinct functions are found in the skeletal muscle. We have identified two pericyte subpopulations based on nestin-GFP expression in muscle blood vessels: type 1 (nestin-GFP−/NG2-DsRed+) and type 2 (nestin-GFP+/NG2-DsRed+)] (Birbrair et al., 2011; Birbrair et al., 2014c). Although both express PDGFRβ, only type-1 pericytes have the fibrogenic capacity (Birbrair et al., 2013d). Future studies should specifically block αv integrins in type-1 pericytes.

Besides perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells, several other skeletal muscle cells have been proposed as the source of collagen production, including fibrocytes (Herzog and Bucala, 2010), resident fibroblasts (Lieber and Ward, 2013), satellite cells (Alexakis et al., 2007), endothelial cells (Zeisberg et al., 2007), nerve-associated cells (Hinz et al., 2012), muscle-derived stem cells (Li and Huard, 2002; Silva et al., 2018), and fibroadipogenic progenitors (Uezumi et al., 2011). Their exact physiological roles in skeletal muscle fibrosis remain unclear. Several of these studies were at least partially in vitro, and cell preparation and grafting may have modified properties that influence their fate in vivo.

An elegant fate-mapping study revealed that during development, perivascular ADAM12-expressing cells give rise to most of the cells that produce collagen in response to skeletal muscle injury (Dulauroy et al., 2012). Another recent study used genetic lineage tracing analysis to show that perivascular tissue-resident Gli1+ cells are key contributors to injury-induced organ fibrosis (Kramann et al., 2015; Sena et al., 2017a; Sena et al., 2017b). Future studies are needed to determine the overlap between PDGFRβ+ and PDGFRα-, ADAM12-, and Gli1-expressing cells and their relative contributions to fibrous tissue deposition in skeletal muscle.

Although collagen I is often cited as the primary extracellular matrix protein expressed by fibroblastic cells in skeletal muscle fibrosis (Gillies and Lieber, 2011), fibrotic cells produce myriad other extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen types III, IV, V, and VI (Zhang et al., 1994), as well as glycoproteins and proteoglycans, such as fibronectin, laminin, and tenascin (Berndt et al., 1994; Hinz, 2007; Magro et al., 1997; Mahida et al., 1997). Perivascular cells are not the only source of all these proteins since resident fibroblasts, inflammatory, and endothelial cells may produce these proteins as well (Azevedo et al., 2017a; Paiva et al., 2017). Production of these various proteins in the skeletal muscle may increase with the specific disease state. Future studies should determine the specific components of the extracellular matrix and their cellular source and clarify the relative contributions of PDGFRβ-, ADAM 12-, and Glil-expressing cells to fibrotic, type I collagen, and any other skeletal muscle cells that produce extracellular matrix components.

Up to now, all studies tracking fibrotic cell formation have analyzed it after skeletal muscle injury. The cellular source of fibrosis during aging and in chronic diseases, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, remains unknown, impeding the development of effective therapies to repair skeletal muscle. Detailed fate-mapping and lineage-tracing experiments in dystrophic and aged mouse models will advance the field significantly.

Murray and colleagues analyzed the role of αv integrins in PDGFRβ-expressing skeletal muscle cells (Murray et al., 2017). However, αv integrins are widely expressed in a variety of cell types in various tissues and are essential to blood vessel formation (Bader et al., 1998). As PDGFRβ-expressing cells are also widely distributed, in PDGFRβ-Cre mice, recombinase expression is not limited to skeletal muscle perivascular cells; PDGFRβ+ cells in other organs are marked as well. Thus, in PDGFRβ-Cre/αv integrin-floxed mice, αv integrin deletion is not restricted to skeletal muscle perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells. Future studies should evaluate the contribution of cells expressing PDGFRβ outside the skeletal muscle to fibrous tissue accumulation.

The focus on perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells has increased with the advent of modem technologies, such as transgenic mouse models and confocal microscopy, and we have greater insight into their varying, sometimes unexpected, physiological and pathological functions. In addition to physical stabilization of the vasculature, these cells participate in the vascular development, maturation, and remodeling. They also regulate vascular permeability and blood flow (Almeida et al., 2017; Enge et al., 2002; Hellstrom et al., 2001; Leveen et al., 1994; Lindahl et al., 1997; Pallone and Silldorff, 2001; Pallone et al., 1998; Pallone et al., 2003; Soriano, 1994) and may affect blood coagulation (Bouchard et al., 1997; Fisher, 2009; Kim, J.A. et al., 2006). In the central nervous system, they collaborate with astrocytes to regulate the functional integrity of the blood–brain barrier (Al Ahmad et al., 2011; Armulik et al., 2010; Bell et al., 2010; Cuevas et al., 1984; Daneman et al., 2010; Dohgu et al., 2005; Kamouchi et al., 2011; Krueger and Bechmann, 2010; Nakagawa et al., 2007; Nakamura et al., 2008; Santos et al., 2017; Shimizu et al., 2008; Thanabalasundaram et al., 2011). Recent studies showed they can function as stem cells (Almeida et al., 2017; Andreotti et al., 2018b; Birbrair and Delbono, 2015; Birbrair et al., 2013a, b; Dias Moura Prazeres et al., 2017; Prazeres et al., 2017), generating other cell types (Coatti et al., 2017), and regulate the function of other stem cells (Andreotti et al., 2017; Asada et al., 2017; Azevedo et al., 2017b; Birbrair and Frenette, 2016; Borges et al., 2017; Guerra et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2016; Lousado et al., 2017). Note that they have some immune functions, regulating lymphocyte activation (Andreotti et al., 2018a; Balabanov et al., 1999; Fabry et al., 1993; Tu et al., 2011; Verbeek et al., 1995), contributing to the clearance of toxic cellular byproducts, attracting innate leukocytes that exit through the sprouting vessels (Stark et al., 2013), and immunosuppressive mechanisms (Sena et al., 2018). What role αv integrins play in the many functions of perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells is unknown. Future studies should explore whether blocking them in these cells affects functions other than tissue fibrosis.

Integrins are transmembrane surface proteins that link the extracellular matrix with the cytoskeleton (Hynes, 2004). Considerable research indicates their pivotal roles and wide involvement in physiological and pathological processes (Ley et al., 2016). Integrins function as heterodimers, with α and β subunits (Lowell and Mayadas, 2012). Future studies should investigate which β integrins known to be associated with αv integrins are essential for skeletal muscle fibrosis. Although fibrous tissue formation and deposition are distinct for each organ physiopathogensis seems to be similar. In 2013, using the same mouse model, Henderson and colleagues showed that depleting αv integrins inhibits fibrosis in the liver, lung, and kidney (Henderson et al., 2013). Future studies should distinguish αv integrins’ role in skeletal muscle fibrosis.

CWHM 12, a small molecule inhibitor of αv integrins, decreases fibrosis development in the liver and lung (Henderson et al., 2013). Murray and colleagues propose its potential use as a therapy for skeletal muscle fibrosis. Before pursuing this avenue, possible side effects should be considered, as mice deficient in αv integrins evidence dramatic vascular disarray (Bader et al., 1998). For instance, several cell types that express αv integrins have been targeted for tumor growth prevention strategies using peptide inhibitors to block neovascularization (Desgrosellier and Cheresh, 2010; Paiva et al., 2018). Integrins also play important roles in normal wound healing and scarring processes (Koivisto et al., 2014; Silva et al., 2018). Unsuccessful attempts to use integrin blockers include the use of the humanized, a4 integrin, monoclonal blocking antibody, natalizumab, for Crohn’s disease treatment, which increased risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (Kleinschmidt-DeMasters and Tyler, 2005; Langer-Gould et al., 2005; Van Assche et al., 2005). Long-term toxicity studies will be needed before CWHM 12 can be used in humans, and its efficacy in models other than mice should be determined. A phase I study designed to examine the safety of a single dose of the integrin αv antagonist GSK3008348 in healthy volunteers began recently and, if successful, will be tested in patients with pulmonary fibrosis (NCT02612051). CWHM 12 was tested only in chemical- or injury-induced fibrosis models; will it be effective in treating the fibrosis associated with aging and chronic diseases?

In conclusion, the study by Murray and colleagues reveals a novel and important role for perivascular cell αv integrins in skeletal muscle fibrosis. However, our understanding of perivascular cell biology in fibrosis is still limited, and future work must elucidate the complexity and interactions of various cellular components and molecules in the skeletal muscle microenvironment during disease progression.

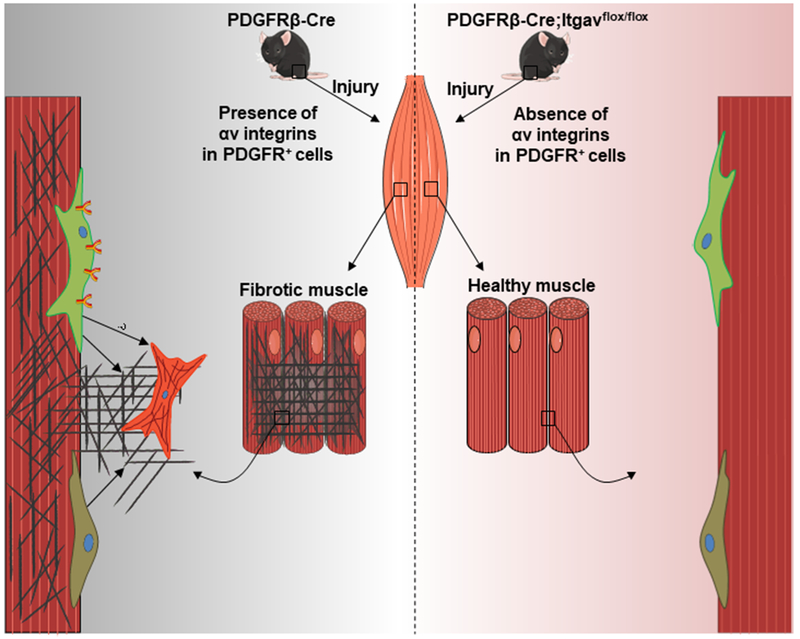

Figure 1. αv integrins on PDGFRβ+ cells in the skeletal muscle support injury-induced fibrosis.

Perivascular PDGFRβ-expressing cells are associated with skeletal muscle blood vessels. Murray and colleagues discovered that they produce fibrous tissue after skeletal muscle injury (Murray et al., 2017). Further, specific genetic ablation of αv integrins from these cells inhibits skeletal muscle fibrosis. With state-of-the-art technologies, future studies will reveal in detail the cellular and molecular components of the skeletal muscle fibrotic microenvironment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Alexander Birbrair is supported by grants from Serrapilheira Institute (G-1708-15285), Próreitoria de Pesquisa/Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (PRPq/UFMG) (Edital 05/2016), FAPEMIG [Rede Mineira de Engenharia de Tecidos e Terapia Celular (REMETTEC, RED-00570-16)], and FAPEMIG [Rede De Pesquisa Em Doenças Infecciosas Humanas E Animais Do Estado De Minas Gerais (RED-00313-16)]. Akiva Mintz is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1R01CA179072-01A1) and an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar grant (124443-MRSG-13-121-01-CDD). Osvaldo Delbono was supported by the NIH (R01AG013934 and R01AG057013).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Affo S, Yu LX, Schwabe RF, 2017. The Role of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Fibrosis in Liver Cancer. Annual review of pathology 12, 153–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Ahmad A, Taboada CB, Gassmann M, Ogunshola OO, 2011. Astrocytes and pericytes differentially modulate blood-brain barrier characteristics during development and hypoxic insult. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 31(2), 693–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexakis C, Partridge T, Bou-Gharios G, 2007. Implication of the satellite cell in dystrophic muscle fibrosis: a self-perpetuating mechanism of collagen overproduction. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 293(2), C661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida VM, Paiva AE, Sena IFG, Mintz A, Magno LAV, Birbrair A, 2017. Pericytes Make Spinal Cord Breathless after Injury. Neuroscientist. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti JP, Lousado L, Magno LAV, Birbrair A, 2017. Hypothalamic Neurons Take Center Stage in the Neural Stem Cell Niche. Cell stem cell 21(3), 293–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti JP, Paiva AE, Prazeres P, Guerra DAP, Silva WN, Vaz RS, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2018a. The role of natural killer cells in the uterine microenvironment during pregnancy. Cellular & molecular immunology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti JP, Prazeres PHDM, Magno LAV, Romano-Silva MA, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2018b. Neurogenesis in the postnatal cerebellum after injury. Int J Dev Neurosci [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Genove G, Betsholtz C, 2011. Pericytes: Developmental, Physiological, and Pathological Perspectives, Problems, and Promises. Developmental Cell 21(2), 193–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Genove G, Mae M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, Johansson BR, Betsholtz C, 2010. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature 468(7323), 557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada N, Kunisaki Y, Pierce H, Wang Z, Fernandez NF, Birbrair A, Ma’ayan A, Frenette PS, 2017. Differential cytokine contributions of perivascular haematopoietic stem cell niches. Nat Cell Biol 19(3), 214–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo PO, Lousado L, Paiva AE, Andreotti JP, Santos GSP, Sena IFG, Prazeres P, Filev R, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2017a. Endothelial cells maintain neural stem cells quiescent in their niche. Neuroscience 363, 62–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo PO, Sena IFG, Andreotti JP, Carvalho-Tavares J, Alves-Filho JC, Cunha TM, Cunha FQ, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2017b. Pericytes modulate myelination in the central nervous system. Journal of cellular physiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader BL, Rayburn H, Crowley D, Hynes RO, 1998. Extensive vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and organogenesis precede lethality in mice lacking all alpha v integrins. Cell 95(4), 507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanov R, Beaumont T, Dore-Duffy P, 1999. Role of central nervous system microvascular pericytes in activation of antigen-primed splenic T-lymphocytes. Journal of neuroscience research 55(5), 578–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JL, Glass WF 2nd, 2011. Renal interstitial fibrosis: a critical evaluation of the origin of myofibroblasts. Contrib Nephrol 169, 73–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, Singh I, LaRue B, Deane R, Zlokovic BV, 2010. Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 68(3), 409–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt A, Kosmehl H, Katenkamp D, Tauchmann V, 1994. Appearance of the myofibroblastic phenotype in Dupuytren’s disease is associated with a fibronectin, laminin, collagen type IV and tenascin extracellular matrix. Pathobiology : journal of immunopathology, molecular and cellular biology 62(2), 55–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, 2017. Stem Cell Microenvironments and Beyond. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 1041, 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Borges IDT, Gilson Sena IF, Almeida GG, da Silva Meirelles L, Goncalves R, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2017a. How Plastic Are Pericytes? Stem cells and development 26(14), 1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Borges IDT, Gilson Sena IF, Almeida GG, da Silva Meirelles L, Goncalves R, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2017b. How plastic are pericytes? Stem cells and development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Delbono O, 2015. Pericytes are Essential for Skeletal Muscle Formation. Stem cell reviews 11(4), 547–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Frenette PS, 2016. Niche heterogeneity in the bone marrow. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1370(1), 82–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Sattiraju A, Zhu D, Zulato G, Batista F, Nguyen VT, Messi ML, Solingapuram Sai KK, Marini FC, Delbono O, Mintz A, 2017c. Novel Peripherally Derived Neural-Like Stem Cells as Therapeutic Carriers for Treating Glioblastomas. Stem cells translational medicine 6(2), 471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Delbono O, 2011. Nestin-GFP transgene reveals neural precursor cells in adult skeletal muscle. PloS one 6(2), el6816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Zhang T, Files DC, Mannava S, Smith T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2014a. Type-1 pericytes accumulate after tissue injury and produce collagen in an organ-dependent manner. Stem cell research & therapy 5(6), 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2013a. Role of pericytes in skeletal muscle regeneration and fat accumulation. Stem cells and development 22(16), 2298–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2013b. Skeletal muscle neural progenitor cells exhibit properties of NG2-glia. Exp Cell Res 319(1), 45–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2013c. Skeletal muscle pericyte subtypes differ in their differentiation potential. Stem Cell Res 10(1), 67–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2013d. Type-1 pericytes participate in fibrous tissue deposition in aged skeletal muscle. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 305(11), C1098–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2014b. Pericytes: multitasking cells in the regeneration of injured, diseased, and aged skeletal muscle. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 6, 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2015. Pericytes at the intersection between tissue regeneration and pathology. Clinical science 128(2), 81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Olson JD, Mintz A, Delbono O, 2014c. Type-2 pericytes participate in normal and tumoral angiogenesis. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 307(1), C25–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges I, Sena I, Azevedo P, Andreotti J, Almeida V, Paiva A, Santos G, Guerra D, Prazeres P, Mesquita LL, Silva LSB, Leonel C, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2017. Lung as a Niche for Hematopoietic Progenitors. Stem cell reviews 13(5), 567–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard BA, Shatos MA, Tracy PB, 1997. Human brain pericytes differentially regulate expression of procoagulant enzyme complexes comprising the extrinsic pathway of blood coagulation. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 17(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BM, 1986. Regeneration of entire skeletal muscles. Federation proceedings 45(5), 1456–1460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatti GC, Frangini M, Valadares MC, Gomes JP, Lima NO, Cavacana N, Assoni AF, Pelatti MV, Birbrair A, de Lima ACP, Singer JM, Rocha FMM, Da Silva GL, Mantovani MS, Macedo-Souza LI, Ferrari MFR, Zatz M, 2017. Pericytes Extend Survival of ALS SOD1 Mice and Induce the Expression of Antioxidant Enzymes in the Murine Model and in IPSCs Derived Neuronal Cells from an ALS Patient. Stem cell reviews. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa MA, Paiva AE, Andreotti JP, Cardoso MV, Cardoso CD, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2018. Pericytes constrict blood vessels after myocardial ischemia. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas P, Gutierrez-Diaz JA, Reimers D, Dujovny M, Diaz FG, Ausman JI, 1984. Pericyte endothelial gap junctions in human cerebral capillaries. Anatomy and embryology 170(2), 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R, Zhou L, Kebede AA, Barres BA, 2010. Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature 468(7323), 562–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA, 2010. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nature reviews. Cancer 10(1), 9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias Moura Prazeres PH, Sena IFG, Borges IDT, de Azevedo PO, Andreotti JP, de Paiva AE, de Almeida VM, de Paula Guerra DA, Pinheiro Dos Santos GS, Mintz A, Delbono O, Birbrair A, 2017. Pericytes are heterogeneous in their origin within the same tissue. Developmental biology 427(1), 6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohgu S, Takata F, Yamauchi A, Nakagawa S, Egawa T, Naito M, Tsuruo T, Sawada Y, Niwa M, Kataoka Y, 2005. Brain pericytes contribute to the induction and up-regulation of blood-brain barrier functions through transforming growth factor-beta production. Brain research 1038(2), 208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulauroy S, Di Carlo SE, Langa F, Eberl G, Peduto L, 2012. Lineage tracing and genetic ablation of ADAM12(+) perivascular cells identify a major source of profibrotic cells during acute tissue injury. Nature medicine 18(8), 1262–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eming SA, Martin P, Tomic-Canic M, 2014. Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Science translational medicine 6(265), 265sr266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enge M, Bjarnegard M, Gerhardt H, Gustafsson E, Kalen M, Asker N, Hammes HP, Shani M, Fassler R, Betsholtz C, 2002. Endothelium-specific platelet-derived growth factor-B ablation mimics diabetic retinopathy. The EMBO journal 21(16), 4307–4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabry Z, Fitzsimmons KM, Herlein JA, Moninger TO, Dobbs MB, Hart MN, 1993. Production of the cytokines interleukin 1 and 6 by murine brain microvessel endothelium and smooth muscle pericytes. Journal of neuroimmunology 47(1), 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, 2009. Pericyte signaling in the neurovascular unit. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation 40(3 Suppl), S13–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL, Sheppard D, Duffield JS, Violette S, 2013. Therapy for fibrotic diseases: nearing the starting line. Science translational medicine 5(167), 167sr161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerl K, Miquerol L, Todorov VT, Hugo CP, Adams RH, Kurtz A, Kurt B, 2015. Inducible glomerular erythropoietin production in the adult kidney. Kidney international 88(6), 1345–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies AR, Lieber RL, 2011. Structure and function of the skeletal muscle extracellular matrix. Muscle & nerve 44(3), 318–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra DAP, Paiva AE, Sena IFG, Azevedo PO, Batista ML Jr., Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2017. Adipocytes role in the bone marrow niche. Cytometry. Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes-Camboa N, Cattaneo P, Sun Y, Moore-Morris T, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Rockenstein E, Masliah E, Peterson KL, Stallcup WB, Chen J, Evans SM, 2017. Pericytes of Multiple Organs Do Not Behave as Mesenchymal Stem Cells In Vivo. Cell stem cell 20(3), 345–359 e345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT, 2008. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 453(7193), 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom M, Gerhardt H, Kalen M, Li X, Eriksson U, Wolburg H, Betsholtz C, 2001. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. The Journal of cell biology 153(3), 543–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson NC, Arnold TD, Katamura Y, Giacomini MM, Rodriguez JD, McCarty JH, Pellicoro A, Raschperger E, Betsholtz C, Ruminski PG, Griggs DW, Prinsen MJ, Maher JJ, Iredale JP, Lacy-Hulbert A, Adams RH, Sheppard D, 2013. Targeting of alphav integrin identifies a core molecular pathway that regulates fibrosis in several organs. Nature medicine 19(12), 1617–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog EL, Bucala R, 2010. Fibrocytes in health and disease. Experimental hematology 38(7), 548–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B, 2007. Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. The Journal of investigative dermatology 127(3), 526–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Prunotto M, Desmouliere A, Varga J, De Wever O, Mareel M, Gabbiani G, 2012. Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling. The American journal of pathology 180(4), 1340–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard J, Li Y, Fu FH, 2002. Muscle injuries and repair: current trends in research. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 84-A(5), 822–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO, 2004. The emergence of integrins: a personal and historical perspective. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology 23(6), 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamouchi M, Ago T, Kitazono T, 2011. Brain pericytes: emerging concepts and functional roles in brain homeostasis. Cellular and molecular neurobiology 31(2), 175–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan JA, Mendelson A, Kunisaki Y, Birbrair A, Kou Y, Arnal-Estape A, Pinho S, Ciero P, Nakahara F, Ma’ayan A, Bergman A, Merad M, Frenette PS, 2016. Fetal liver hematopoietic stem cell niches associate with portal vessels. Science 351(6269), 176–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Tran ND, Li Z, Yang F, Zhou W, Fisher MJ, 2006. Brain endothelial hemostasis regulation by pericytes. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 26(2), 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KK, Kugler MC, Wolters PJ, Robillard L, Galvez MG, Brumwell AN, Sheppard D, Chapman HA, 2006. Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103(35), 13180–13185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL, 2005. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. The New England journal of medicine 353(4), 369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto L, Heino J, Hakkinen L, Larjava H, 2014. Integrins in Wound Healing. Advances in wound care 3(12), 762–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramann R, Schneider RK, DiRocco DP, Machado F, Fleig S, Bondzie PA, Henderson JM, Ebert BL, Humphreys BD, 2015. Perivascular Gli1+ progenitors are key contributors to injury-induced organ fibrosis. Cell stem cell 16(1), 51–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger M, Bechmann I, 2010. CNS pericytes: concepts, misconceptions, and a way out. Glia 58(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, Bollen AW, Pelletier D, 2005. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. The New England journal of medicine 353(4), 375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBleu VS, Taduri G, O’Connell J, Teng Y, Cooke VG, Woda C, Sugimoto H, Kalluri R, 2013. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Nature medicine 19(8), 1047–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leveen P, Pekny M, Gebre-Medhin S, Swolin B, Larsson E, Betsholtz C, 1994. Mice deficient for PDGF B show renal, cardiovascular, and hematological abnormalities. Genes & development 8(16), 1875–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K, Rivera-Nieves J, Sandborn WJ, Shattil S, 2016. Integrin-based therapeutics: biological basis, clinical use and new drugs. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 15(3), 173–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Huard J, 2002. Differentiation of muscle-derived cells into myofibroblasts in injured skeletal muscle. The American journal of pathology 161(3), 895–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber RL, Friden J, 2002. Spasticity causes a fundamental rearrangement of muscle-joint interaction. Muscle & nerve 25(2), 265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber RL, Ward SR, 2013. Cellular mechanisms of tissue fibrosis. 4. Structural and functional consequences of skeletal muscle fibrosis. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 305(3), C241–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Leveen P, Betsholtz C, 1997. Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science 277(5323), 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lousado L, Prazeres P, Andreotti JP, Paiva AE, Azevedo PO, Santos GSP, Filev R, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2017. Schwann cell precursors as a source for adrenal gland chromaffin cells. Cell death & disease 8(10), e3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell CA, Mayadas TN, 2012. Overview: studying integrins in vivo. Methods in molecular biology 757, 369–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magro G, Fraggetta F, Colombatti A, Lanzafame S, 1997. Myofibroblasts and extracellular matrix glycoproteins in palmar fibromatosis. General & diagnostic pathology 142(3–4), 185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahida YR, Beltinger J, Makh S, Goke M, Gray T, Podolsky DK, Hawkey CJ, 1997. Adult human colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts express extracellular matrix proteins and cyclooxygenase-1 and -2. The American journal of physiology 273(6 Pt 1), G1341–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FJ, Chisholm A, Collard HR, Flaherty KR, Myers J, Raghu G, Walsh SL, White ES, Richeldi L, 2017. The diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current and future approaches. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 5(1), 61–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X, Bellayr I, Walters T, Li Y, 2010. Mediators leading to fibrosis - how to measure and control them in tissue engineering. Operative techniques in orthopaedics 20(2), 110–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Felix JM, Gonzalez-Nunez M, Martinez-Salgado C, Lopez-Novoa JM, 2015. TGF-beta/BMP proteins as therapeutic targets in renal fibrosis. Where have we arrived after 25 years of trials and tribulations? Pharmacology & therapeutics 156, 44–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray IR, Gonzalez ZN, Baily J, Dobie R, Wallace RJ, Mackinnon AC, Smith JR, Greenhalgh SN, Thompson AI, Conroy KP, Griggs DW, Ruminski PG, Gray GA, Singh M, Campbell MA, Kendall TJ, Dai J, Li Y, Iredale JP, Simpson H, Huard J, Peault B, Henderson NC, 2017. alphav integrins on mesenchymal cells regulate skeletal and cardiac muscle fibrosis. Nature communications 8(1), 1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Deli MA, Nakao S, Honda M, Hayashi K, Nakaoke R, Kataoka Y, Niwa M, 2007. Pericytes from brain microvessels strengthen the barrier integrity in primary cultures of rat brain endothelial cells. Cellular and molecular neurobiology 27(6), 687–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kamouchi M, Kitazono T, Kuroda J, Matsuo R, Hagiwara N, Ishikawa E, Ooboshi H, Ibayashi S, Iida M, 2008. Role of NHE1 in calcium signaling and cell proliferation in human CNS pericytes. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 294(4), H1700–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiga M, Horie T, Kuwabara Y, Nagao K, Baba O, Nakao T, Nishino T, Hakuno D, Nakashima Y, Nishi H, Nakazeki F, Ide Y, Koyama S, Kimura M, Hanada R, Nakamura T, Inada T, Hasegawa K, Conway SJ, Kita T, Kimura T, Ono K, 2017. MicroRNA-33 Controls Adaptive Fibrotic Response in the Remodeling Heart by Preserving Lipid Raft Cholesterol. Circulation research 120(5), 835–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly S, 2017. Epigenetics in fibrosis. Molecular aspects of medicine 54, 89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlund D, Handly-Santana A, Biffi G, Elyada E, Almeida AS, Ponz-Sarvise M, Corbo V, Oni TE, Hearn SA, Lee EJ, Chio II, Hwang CI, Tiriac H, Baker LA, Engle DD, Feig C, Kultti A, Egeblad M, Fearon DT, Crawford JM, Clevers H, Park Y, Tuveson DA, 2017. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. The Journal of experimental medicine 214(3), 579–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva AE, Lousado L, Almeida VM, Andreotti JP, Santos GSP, Azevedo PO, Sena IFG, Prazeres PHDM, Borges IT, Azevedo V, Birbrair A, 2017. Endothelial cells as precursors for osteoblasts in the metastatic prostate cancer bone. Neoplasia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva AE, Lousado L, Guerra DAP, Azevedo PO, Sena IFG, Andreotti JP, Santos GSP, Goncalves R, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2018. Pericytes in the premetastatic niche. Cancer research In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallone TL, Silldorff EP, 2001. Pericyte regulation of renal medullary blood flow. Experimental nephrology 9(3), 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallone TL, Silldorff EP, Turner MR, 1998. Intrarenal blood flow: microvascular anatomy and the regulation of medullary perfusion. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology 25(6), 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallone TL, Zhang Z, Rhinehart K, 2003. Physiology of the renal medullary microcirculation. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 284(2), F253–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prazeres P, Almeida VM, Lousado L, Andreotti JP, Paiva AE, Santos GSP, Azevedo PO, Souto L, Almeida GG, Filev R, Mintz A, Goncalves R, Birbrair A, 2017. Macrophages Generate Pericytes in the Developing Brain. Cellular and molecular neurobiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockey DC, Bell PD, Hill JA, 2015. Fibrosis--A Common Pathway to Organ Injury and Failure. The New England journal of medicine 373(1), 96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos GSP, Prazeres P, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2017. Role of pericytes in the retina. Eye. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholten D, Reichart D, Paik YH, Lindert J, Bhattacharya J, Glass CK, Brenner DA, Kisseleva T, 2011. Migration of fibrocytes in fibrogenic liver injury. The American journal of pathology 179(1), 189–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena IFG, Borges IT, Lousado L, Azevedo PO, Andreotti JP, Almeida VM, Paiva AE, Santos GSP, Guerra DAP, Prazeres P, Souto L, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2017a. LepR+ cells dispute hegemony with Gli1+ cells in bone marrow fibrosis. Cell cycle, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena IFG, Paiva AE, Prazeres P, Azevedo PO, Lousado L, Bhutia SK, Salmina AB, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2018. Glioblastoma-activated pericytes support tumor growth via immunosuppression. Cancer Med [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena IFG, Prazeres P, Santos GSP, Borges IT, Azevedo PO, Andreotti JP, Almeida VM, Paiva AE, Guerra DAP, Lousado L, Souto L, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2017b. Identity of Gli1+ cells in the bone marrow. Experimental hematology 54, 12–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu F, Sano Y, Maeda T, Abe MA, Nakayama H, Takahashi R, Ueda M, Ohtsuki S, Terasaki T, Obinata M, Kanda T, 2008. Peripheral nerve pericytes originating from the blood-nerve barrier expresses tight junctional molecules and transporters as barrier-forming cells. Journal of cellular physiology 217(2), 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva WN, Prazeres P, Paiva AE, Lousado L, Turquetti AOM, Barreto RSN, de Alvarenga EC, Miglino MA, Goncalves R, Mintz A, Birbrair A, 2018. Macrophage-derived GPNMB accelerates skin healing. Experimental dermatology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P, 1994. Abnormal kidney development and hematological disorders in PDGF beta-receptor mutant mice. Genes & development 8(16), 1888–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark K, Eckart A, Haidari S, Tirniceriu A, Lorenz M, von Bruhl ML, Gartner F, Khandoga AG, Legate KR, Pless R, Hepper I, Lauber K, Walzog B, Massberg S, 2013. Capillary and arteriolar pericytes attract innate leukocytes exiting through venules and ‘instruct’ them with pattern-recognition and motility programs. Nature immunology 14(1), 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanabalasundaram G, Schneidewind J, Pieper C, Galla HJ, 2011. The impact of pericytes on the blood-brain barrier integrity depends critically on the pericyte differentiation stage. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 43(9), 1284–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal VJ, Zhou Y, Gaggar A, Duncan SR, 2014. Fibrosis: ultimate and proximate causes. The Journal of clinical investigation 124(11), 4673–4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Li Y, Smith DS, Sheibani N, Huang S, Kern T, Lin F, 2011. Retinal pericytes inhibit activated T cell proliferation. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 52(12), 9005–9010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uezumi A, Ito T, Morikawa D, Shimizu N, Yoneda T, Segawa M, Yamaguchi M, Ogawa R, Matev MM, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S, Tsujikawa K, Tsuchida K, Yamamoto H, Fukada S, 2011. Fibrosis and adipogenesis originate from a common mesenchymal progenitor in skeletal muscle. Journal of cell science 124(Pt 21), 3654–3664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, Dubois B, Vermeire S, Noman M, Verbeeck J, Geboes K, Robberecht W, Rutgeerts P, 2005. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn’s disease. The New England journal of medicine 353(4), 362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek MM, Westphal JR, Ruiter DJ, de Waal RM, 1995. T lymphocyte adhesion to human brain pericytes is mediated via very late antigen-4/vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 interactions. Journal of immunology 154(11), 5876–5884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler EA, Bell RD, Zlokovic BV, 2010. Pericyte-specific expression of PDGF beta receptor in mouse models with normal and deficient PDGF beta receptor signaling. Mol Neurodegener 5, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn TA, 2008. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. The Journal of pathology 214(2), 199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, Yuan X, Pu WT, Roberts AB, Neilson EG, Sayegh MH, Izumo S, Kalluri R, 2007. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nature medicine 13(8), 952–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Rekhter MD, Gordon D, Phan SH, 1994. Myofibroblasts and their role in lung collagen gene expression during pulmonary fibrosis. A combined immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization study. The American journal of pathology 145(1), 114–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumstein MA, Jost B, Hempel J, Hodler J, Gerber C, 2008. The clinical and structural long-term results of open repair of massive tears of the rotator cuff. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 90(11), 2423–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]