Abstract

Affect and its object are separable, so that the same affective reaction can have different effects. Relevant principles from the affect-as-information approach include: (1) The impact of affect depends on implicit attributions -- what it appears to be about. (2) Affect is always taken to be about whatever is currently mentally accessible. Affective reactions can therefore serve as appraisals of objects of judgment or of initial thoughts and opinions about such objects, when they are more accessible. During problem solving, affect can serve as appraisals of thought style rather than thought content. Then, (3) positive and negative affect serve as go and stop signals for current inclinations. Affective influences on cognition are therefore not fixed, but malleable and context-dependent.

Introduction

Emotions are generally about something specific [1]. When frightened by a snake, the object is clear. The object may be less clear for diffuse affective states, such as anxiety, and still less clear for minimal or unconscious affective reactions. Regardless of whether tightly linked to an object or not, the impact of affect on thought and action depends on attributions about what it concerns. This attribution principle comes from the affect-as-information approach to understanding the affect-cognition connection [2, 3, 4, 5].

Other principles include: (2) The immediacy principle – that the object of affect is always whatever is in mind at the time -- and (3) the processing principle -- that positive and negative affect can act as go and stop signals for current and anticipated thought and action [2, 6].

The Attribution Principle

Affective reactions and their objects are separable, which allows scientists to observe how affect influences cognition [5, 7]. Freud [8] elaborated this idea in his early theory. His notion of repression, for example, was that affect could be separated from unacceptable ideas, rendering the ideas unconscious and eliminating the distress. But the affect could then attach itself to a substitute idea. Defense mechanisms (e.g., displacement) and symptoms (e.g., hysteria) were examples of attributions of affect to substitute objects. He analyzed symbols and dreams to trace this wandering affect, and the talking cure was intended to reunite it with its original idea. Contemporary emotion theory is very different than Freud’s, but he gauged correctly the importance of the separability of affect and its object for understanding affective influence.

Research

The continuous flash suppression technique [9] is one method of separating affect from its source. A recent study [10] involved showing a fear face to one eye while high-contrast, flashing Mondrian patterns were shown to the other eye. Since attention is attracted by colorful, moving patterns, participants remained unaware of seeing the static, fear image. Control participants were fully aware of the source of affect, because the fear face appeared in both eyes. Participants then saw novel, neutral faces, which they rated for likeability.

FMRI Imaging showed similar amygdala activation in the aware and unaware groups, but the neutral faces became more negative only for the unaware group. The inaccessibility of the source allowed negative affect to be misattributed to the neutral faces. The same phenomenon appeared in related studies [11, 12]. This research shows dramatically how implicit, automatic attributions guide affective influences on the brain [13] and on judgment. Consistent with the attribution principle, the impact of affect depended on its apparent object.

Application

The same principle can also illuminate events outside the lab. As applied to mental health, recent research shows that individuals capable of making precise attributions for their distress are less susceptible to anxiety and depression and also to maladaptive coping, such as binge drinking, aggression, or self-injury [14].

The 2016 U.S. presidential election provides a political application. Incomes and opportunities had continued to decline for working families and to rise for high earners. However, the anger among white working-class voters was not attributed to their economic exploitation but instead to the presence of immigrants and aliens [15]. According to the attribution principle, had they attributed their distress accurately, anti-immigrant messages would have been ineffective. But constant repetition of the immigrant theme ensured its cognitive accessibility, illustrating a second principle of affective influence -- the immediacy principle that affect is always experienced as being about whatever is mentally accessible at the time [2, 6].

The Immediacy Principle

If the impact of affect depends on what is in mind, then the timing of what comes to mind should be important. Research finds that evaluative conditioning is most reliable when neutral stimuli (e.g., faces) and evaluative stimuli (e.g., snakes) appear simultaneously [16]. They are then confusable, allowing affect to be misattributed from one source to another. Other studies too show conditioning mainly when misattribution is likely, including when: (a) the stimuli appear close together, (b) participants’ shift their gaze between them, and (3) neutral stimuli are especially salient [17].

Association

When do affective associations influence evaluations? (For a review, see [18]. Analyses of 1000 television commercials found that associations of products with the emotional tone of ads has a substantial impact on product evaluations [19]. That research raises a number of questions. For example, would Batman’s constant association with crime lower evaluations of him? Does it matter that he is only associated because he fights crime? Such qualifications do help, but only when presented during the affective association. Later qualifications are ineffective [20]. Hence, repeated affective associations in advertising [19] and politics [21] may affect us despite subsequent reasoning [22].

Goals

If the impact of affect depends on its object, does the same process apply to goals? Research shows that attributions hold the key [23]. Associating positive affect with goals can increase goal commitment and performance. But when affect is attributed to progress toward the goal, rather than the goal itself, the effect reverses. Then, positive affect implies good progress, which reduces effort, and negative affect, implies poor progress, which increases effort.

Action

Positive affect that is associated with a particular action should confer positive value on the action and increase engagement with it. Relevant research [24] involved the action of pressing the space bar followed by seeing words referring to objects (e.g., “flute”), which had been associated with hearing positive (or neutral) words (e.g., “nice”). When the now positive objects appeared after (but not before) the action, they effectively motivated further effortful action. The results show the importance of what is in mind at the time of an affective reaction, because such accessibility governs what becomes the object of affect.

Persuasion

Attributions also govern affective influences on persuasion [25]. When affect comes before persuasive messages, it is experienced as a reaction to the message. Thus, negative affect leads to rejection of weak messages, whereas positive affect makes them seem acceptable. But that reverses when affect comes after persuasive arguments, because affect then seems like a reaction to thoughts about the arguments. Weak arguments elicit negative thoughts and positive affect says “Go” to them, leading to message rejection. But negative affect, devalues those negative thoughts, leading weak arguments to seem acceptable. Again, implicit attributions are key, which reflect whether the messages or thoughts about them was more accessible when affect was induced.

Judgment

The immediacy principle allows strong predictions about judgment, including reversal of the usual mood-congruent judgment pattern. In one experiment, participants rated their liking for a product associated with famed cyclist Lance Armstrong just after he admitted using performance-enhancing drugs [26]. Participants read about Armstrong and then described a happy or sad life experience of their own. Their initial negative thoughts about Armstrong were thus accessible to become the object of affect. As a result, happy mood led, not to mood-congruent leniency, but to strong rejection of the product, while sad mood led to less harsh rejection. Rather than leading to rejection of Armstrong, negative affect led to rejection of initial negative opinions about Armstrong, producing mood-incongruent rather than mood-congruent judgment. A year later, a similar drug scandal centered on star baseball player Alex Rodriguez (A-Rod). The experiment was repeated, and again, happy moods yielded more negative ratings than sad moods.

Big Data

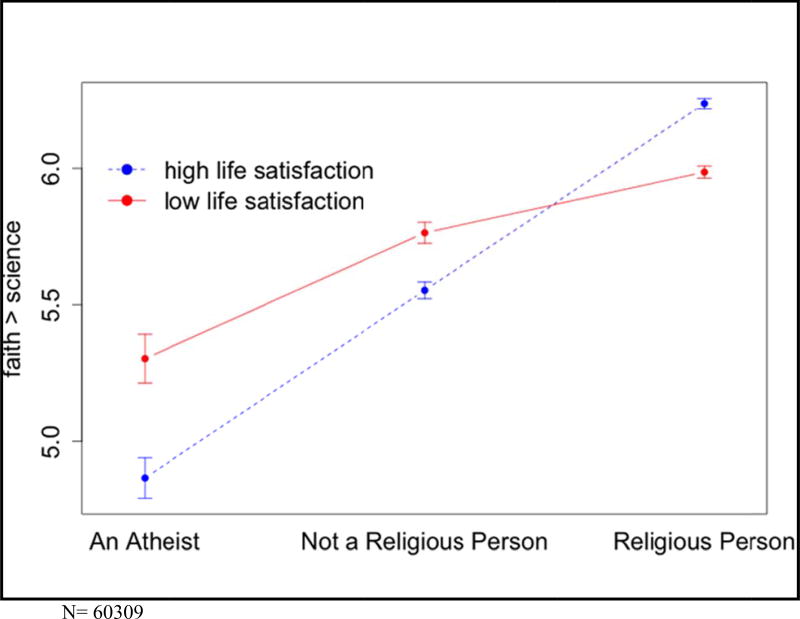

Since people often have initial thoughts and opinions about what they evaluate, few evaluative judgments are made from scratch. Does the discovery that such thoughts can become objects of affect apply outside the lab? One study (Alexander J. Schiller, PhD thesis, University of Virginia, 2017) analyzed 60,000 responses to the statement: “We depend too much on science and not enough on faith.” Ratings of life satisfaction served as a measure of general affect. “Religious” people generally agreed with the statement, whereas “Nonreligious” people and “Atheists” disagreed. Consistent with our initial experiments, this pattern was exaggerated among happy individuals and weaker among unhappy individuals, so that nonreligious people disagreed more when happy than sad. The same pattern emerged in a second sample of 77,000, both indicating that respondents’ thoughts about religion had been the object of affect.

The same pattern also appeared among 1563 “Liberal,” “Moderate,” and “Conservative” respondents to questions about gun control in the American National Election Survey (Alexander J. Schiller, PhD thesis, University of Virginia, 2017). Consistent with the hypothesis, positive affect led conservatives to oppose and liberals to favor gun control with greater confidence than did negative affect. These results involved chronic levels of affect rather than temporary moods. They suggest that adaptation, if it occurs, does not dilute the informativeness of affect. Indeed, we know that experiences of depression and anxiety continue to fuel pessimism despite their chronicity.

The conclusion from experimental and survey data is that affect is sometimes experienced as an evaluation of one’s thoughts and initial opinion rather than of the target of judgment itself. This discovery reflects the attribution principle (the impact of affect depends on its object) and the immediacy principle (the object of affect is whatever is mentally accessible at the time) [2, 6, 26]. As in dog training, rewards influence only the currently most accessible response. Since few judgments are made from scratch, affect sometimes signals confidence or doubt about one’s own thoughts and inclinations.

The Affective Processing Principle

Affect regulates cognitive processing as well as judgment. Studies indicate that happy mood promotes and sad mood inhibits many standard cognitive phenomena, including semantic priming, flanker effects, false memories, schema-based memory phenomena, category-level thinking, heuristic reasoning, and stereotyping [26]. More generally, positive affect broadens attention both perceptually and cognitively [27, 28, 29, 30]1

Global Focus

Most explanations assume a fixed connection between happy mood and global focus. But recent discoveries support the processing principle (positive and negative affect serve as go and stop signals for currently accessible cognitions and inclinations) [2, 6]. In this view, affective impact should depend on what is most accessible [32]. As a test, research primed either a global or local focus to vary their accessibility [33].

The results showed that rather than always eliciting a global focus, positive mood enhanced whatever was accessible -- global responses after global priming and local responses after local priming. The pattern was then replicated using different methods. Neither study found evidence of a fixed affect-processing connection. Because a moderately global focus is naturally dominant for most people [34, 35], positive affect apparently broadens attention simply by empowering that default orientation.

Impression Formation

Positive affect promotes and negative affect inhibits responses that are naturally dominant also when forming impressions of others. Examples include the fundamental attribution error [36] and biases from first impressions [37] or a person’s visual prominence [38]. People also tend to see out-group members as more homogeneous than they are, and this too is more pronounced in happy than sad moods. But that occurs only when a global focus is most accessible [39]. When a local focus was made more accessible, the reverse occurred, and happy moods led outgroup members to be viewed as individuals rather than as all alike. The impact of affect is thus malleable, depending on what is made accessible.

Anger

Although anger is negative regarding outcomes [40], it is positive about one’s own perspective. This positivity should therefore empower accessible thoughts and inclinations, just as positive affect does. A recent study examined the broad-abstract vs. narrow-concrete nature of people’s self-descriptions when angry, sad, or fearful [41]. Anger led to self-descriptions that were more abstract or less concrete than sadness and fear. The results are thus consistent with the idea that, like happiness, anger says “Go” to the naturally accessible global focus, thereby generating abstract rather than concrete concepts. It should be noted that other features of affective states can also empower accessible thoughts and inclinations, including arousal [42], certainty [43], feeling entitled [44], and approach motivation [45].

Creativity

Past studies have often found that happy mood spurs creativity [46]. But there too, the effect appears malleable [47]. Specifically, happy moods lead to creative responses after global priming, but to less creativity after local priming. Again, affect either empowered or inhibited whatever orientation was most accessible. Do such results threaten the generalization that happy moods lead to creativity? No, but the effect is indirect. Creativity flowed from a naturally-accessible global mindset, which happy mood enhanced and sad mood inhibited.

Conclusions

This review has emphasized research bearing on three principles of affective influence [6], which indicate that: (1) understanding affective influence requires knowing how individuals attribute their affect, (2) attributions for affect are governed by currently accessible cognitions, so that sometimes one’s own thoughts become the object, and (3) consistent with current constructivist accounts of emotion [48], the consequences of affect are also constructed; that is, malleable and context specific. Future research might ask under what conditions internal thoughts become more accessible than objects in the environment.

Fig 1.

Respondents to the World Values Survey (N=60309) indicate agreement that, “We depend too much on science and not enough on faith.” Significant interaction shows more extreme agreement and disagreements for happy than less happy respondents (Alexander J. Schiller, PhD thesis, University of Virginia, 2017).

Fig 2.

From the American National Election Survey (2013), 1563 Liberal, Moderate, and Conservative respondents indicate their level of pro-gun attitudes, Significant interaction shows more extreme agreement and disagreements for happy than less happy respondents, F(1, 1437) = 43.10 p < .001, Error bars = 95% confidence interval. (Alexander J. schiller, PhD thesis, University of Virginia, 2017).

Highlights.

The impact of positive and negative affect depends on what they seem to be about

Affect is automatically attributed to what is most mentally accessible at the time

Objects of judgment can be less mentally accessible than opinions about them

Positive affect says go and negative affect says stop to current modes of thought

Affective influences on thought are not fixed, but vary with what is most accessible

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [MH 50074] and the National Science Foundation [(BCS-1252079s].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Failures to find mood effects on attention can occur when investigators insert mood manipulation checks before the cognitive task, making the mood induction salient and discouraging the attribution of affect as a reaction to the task (e.g., [31]).

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

- 1.Clore GL. What is an emotion? In: Davidson R, Shackman A, Fox A, Lapate R, editors. The Nature of Emotion: a volume of short essays addressing fundamental questions in emotion. Oxford University Press; 2017a. [Google Scholar]

- *2.Clore GL. The impact of affect depends on its object. In: Davidson R, Shackman A, Fox A, Lapate R, editors. The Nature of Emotion: a volume of short essays addressing fundamental questions in emotion. Oxford University Press; 2017b. Provides a brief, accessible discussion of a new view of how affect can influence judgment and thought and also learning and performance. In this view, the influence of affect is malleable rather than fixed, and it serves as feedforward information about the likely relevance and value of currently accessible thoughts and inclinations. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaked A, Clore GL. Breaking the world to make it whole again: Attribution in the construction of emotion. Emotion Review. 2016;9:27–35. doi: 10.1177/1754073916658250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarz N, Clore GL. Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45:513–523. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarz N, Clore GL. In: Social Psychology. A Handbook of Basic Principles. 2. Higgins ET, Kruglanski A, editors. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 385–407. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clore GL, Gasper K, Garvin E. Affect as information. In: Forgas JP, editor. Handbook of Affect and Social Cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forgas JP. Mood and judgment: The Affect Infusion Model (AIM) Psychological Bulletin. 1995;116:39–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freud S. The defence neuro-psychoses. In: Jones E, editor. Sigmund Freud: Collected papers. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1894/1959. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuchiya N, Koch C. Continuous flash suppression reduces negative afterimages. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1096–1101. doi: 10.1038/nn1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *10.Lapate RC, Rokers B, Tromp DPM, Orfali NS, Oler JA, Doram ST, Adluru N, Alexander AL, Davidson RJ. Awareness of emotional stimuli determines the behavioral consequences of amygdala activation and amygdala-prefrontal connectivity. Scientific Reports. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep25826. Article number: 25826. doi: 10.1038/srep25826 Imaging finds equal levels of amygdala response whether fear faces are consciously or unconsciously presented. But such responses influence perceptions of neutral faces only when participants lacked awareness of the source of the affect, which then allows the affect to be misattributed to new faces. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lapate RC, Rokers B, Li T, Davidson RJ. Non-conscious emotional activation colors first impressions: A regulatory role for conscious awareness. Psychological Science. 2014;2:349–357. doi: 10.1177/0956797613503175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson E, Siegel E, White D, Barrett LF. Out of sight but not out of mind: Unseen affective faces influence evaluations and social impressions. Emotion. 2012;12:1210–1221. doi: 10.1037/a0027514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapate RC. Regulatory benefits of conscious awareness: insights from the emotion misattribution paradigm and a role for lateral prefrontal cortex. In: Fox AS, Lapate RC, Shackman AJ, Davidson RJ, editors. The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashdan TB, Barrett LF, McKnight PE. Unpacking emotion differentiation: Transforming unpleasant experience by perceiving distinctions in negativity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2015;24:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pew Research Center. 2017 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/09/behind-trumps-victory.

- 16.Hütter M, Sweldens S. Implicit misattribution of evaluative responses: Contingency-unaware evaluative conditioning requires simultaneous stimulus presentations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2013;142:638–643. doi: 10.1037/a0029989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones CR, Fazio RH, Olson MA. Implicit misattribution as a mechanism underlying evaluative conditioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:933–948. doi: 10.1037/a0014747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clore GL, Schnall S. The influence of affect on attitude. In: Albarracín D, Johnson BT, Zanna MP, editors. Handbook of attitudes. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pham MT, Geuens M, De Pelsmacker P. The influence of ad-evoked feelings on brand evaluations: Empirical generalizations from consumer responses to more than 1,000 TV commercials. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 2013;30:383–394. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu X, Gawronski B, Balas R. Propositional versus dual-process accounts of evaluative conditioning: The effects of co-occurrence and relational information on implicit and explicit evaluations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2017;43:17–32. doi: 10.1177/0146167216673351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowling CM, Wichowsky A. Attacks without consequence? Candidates, parties, groups, and the changing face of negative advertising. American Journal of Political Science, 2015. 2015;59:19–36. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gawronski B, Mitchell DGV, Balas R. Is evaluative conditioning really uncontrollable? A comparative test of three emotion-focused strategies to prevent the acquisition of conditioned preferences. Emotion. 2015;15:556–568. doi: 10.1037/emo0000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fishbach A, Eyal T, Finkelstein SR. How positive and negative feedback motivate goal pursuit. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2010;4:517–530. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marien H, Aarts H, Custers R. The interactive role of action-outcome learning and positive affective information in motivating human goal-directed behavior. Motivation Science. 2015;1:165–183. [Google Scholar]

- *25.Petty RE, Briñol P. Emotion and persuasion: Cognitive and metacognitive processes impact attitudes. Cognition and Emotion. 2015;29:1–26. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.967183. Reviews evidence for five processes that influence attitudes and persuasion at different stages of the cognitive elaboration of information. Of particular interest are findings that the more one thinks about a message, the more likely are thoughts (rather than the targets of judgment) to become objects of affect. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clore GL, Schiller AJ. New light on the affect-cognition connection. In: Barrett LF, Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, editors. The Handbook of Emotions. 4. New York: Guilford Press; 2016. pp. 532–546. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Easterbrook JA. The effect of emotion on cue utilization and the organization of behavior. Psychological Review. 1959;66:183–201. doi: 10.1037/h0047707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fredrickson BL, Branigan C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion. 2005;19:313–332. doi: 10.1080/02699930441000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gasper K, Clore GL. Attending to the big picture: Mood and global vs. local Mood and global vs. local processing of visual information. Psychological Science. 2002;13:34–40. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowe G, Hirsh JB, Anderson AK. Positive affect increases the breadth of attentional selection. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:383–388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605198104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bendall RCA, Thompson C. Emotion has no impact on attention in a change detection flicker task. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015 2015 Oct 20; doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Huntsinger JR, Isbell LM, Clore GL. The affective control of thought: Malleable, not fixed. Psychological Review. 2014;121:600–618. doi: 10.1037/a0037669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huntsinger JR, Clore GL, Bar-Anan Y. Mood and global-local focus: Priming a local focus reverses the link between mood and global-local processing. Emotion. 2010;10:722–726. doi: 10.1037/a0019356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navon D. The forest before trees: The precedence of global features in visual perception. Cognitive Psychology. 1977;9:353–383. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vallacher RR, Wegner DM. What do people think they’re doing? Action identification and human behavior. Psychological Review. 1987;94:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forgas JP. On being happy but mistaken: Mood effects on the fundamental attribution error. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:318–331. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forgas JP. Can negative affect eliminate the power of first impressions? Affective influences on primacy and recency effects in impression formation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2011;47:425–429. doi.org/101016/jjesp201011005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forgas JP. Why do highly visible people appear more important? Affect mediates visual fluency effects in impression formation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2015;58:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *39.Isbell LM, Lair EC, Rovenpor D. The impact of affect on out-group judgments depends on dominant information processing styles: Evidence from incidental and integral affect paradigms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2016;42:485–497. doi: 10.1177/0146167216634061. Reports studies finding that people in happy moods tend to see members of out-groups as homogeneous only when a global rather than a local processing style is dominant. When a local style is made momentarily dominant, happy mood promotes individuation in perception of out-group members. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harmon-Jones E, Harmon-Jones C. Anger. In: Barrett LF, Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, editors. Handbook of Emotions. 4. New York: Guilford Publications; 2016. pp. 774–791. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isbell LM, Rovenpor DR, Lair EC. The impact of negative emotions on self-concept abstraction depends on accessible information processing styles. Emotion. 2016;16:1040–1049. doi: 10.1037/emo0000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storbeck J, Clore GL. Affective arousal as information: How affective arousal influences judgments, learning, and memory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:1824–1843. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faraji-Rad A, Pham MT. Uncertainty increases the reliance on affect in decisions. Journal of Consumer Research. 2017;44:1–21. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucw073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zitek EM, Vincent LC. Deserve and diverge: Feeling entitled makes people more creative. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2015;56:242–248. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gable PA, Browning L, Harmon-Jones E. Affect, motivation, and cognitive scope. In: Braver TA, editor. Motivation and Cognitive Control. London: Routledge; 2015. pp. 164–187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis MA. Understanding the relationship between mood and creativity: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2009;108:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *47.Huntsinger JR, Ray C. A flexible influence of affective feelings on creative and analytic performance. Emotion. 2016;16:826–837. doi: 10.1037/emo0000188. Presents research discovering that the impact of positive affect on creativity and heuristic processing is not direct, as often assumed, but can be can be reversed by making a local cognitive focus temporarily more accessible than the usual global focus. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrett LF. How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2017. [Google Scholar]