Abstract

The Problem

Mental health issues such as depression and neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) (e.g. agitation, aggression, rejection of care, wandering) are prevalent among residents in Assisted Living Facilities (ALF). Historically, these issues have only been treated with medications that can have a high risk of adverse effects in this population. This paper presents a scoping review of nonpharmacological interventions tested in ALFs for two of the most prevalent mental health issues: depression and NPS.

Key Findings

Thirteen studies met inclusion criteria. Of those, eight (61.5%) found positive outcomes. Activity based and music therapy that utilize customization to interests and abilities showed the most promise.

Tips for Success

Based on findings we offer five recommendations: 1) adopt evidence-based or evidence-informed interventions; 2) use tailored activity as a therapeutic modality; 3) adopt new training approaches for staff; 4) use emerging technologies for training and intervention; and 5) participate in practice based research.

Keywords: Assisted Living Facility, mental health, dementia, depression

INTRODUCTION

With over 30,000 Assisted Living Facilities (ALF) in the United States caring for more than 730,000 residents, managing mental health issues has become increasingly challenging, particularly depression (Caffrey, Harris-Kojetin, & Sengupta, 2015; Zimmerman, Sloane, & Reed, 2014) and dementia-related neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) (Rosenblatt et al., 2004). Rates reported for depressive symptoms vary widely: some studies estimating 25% of assisted living residents with symptoms (Seitz, Purandare, & Conn, 2010; Watson et al., 2006) to as high as 75% for residents with cognitive impairment or dementia (Caffrey et al., 2015; Gruber-Baldini, Boustani, Sloane, & Zimmerman, 2004; Zimmerman et al., 2014; Zwijsen et al., 2014). Antidepressants are the primary treatment for depression but it has been found that as few as 43% of those with depression are receiving treatment (Watson et al., 2006).

Similarly, NPS or behaviors such as rejection of care, agitation, and aggression are highly prevalent among ALF residents. NPS are experienced by almost all persons with dementia at some point during the disease process (Lyketsos et al., 2012), and are associated with staff burnout, turnover and stress, heightened risk for resident abuse, and ongoing distress in families who often must help staff manage behaviors. NPS can also result in expulsion of residents (Brodaty, Draper, & Low, 2003; Choi, Flynn, & Aiken, 2012; Miyamoto, Tachimori, & Ito, 2010; Rosenblatt et al., 2004).

Although 58% of ALFs report having programs specifically for persons with dementia (Zwijsen et al., 2014), these facilities often do not use evidence-informed strategies or evidence-based programs that target NPS or other mental health issues. Typically, staff have some knowledge of dementia but have a poor understanding of how to actively prevent and manage behaviors or depressive symptoms (Park-Lee, Sengupta, & Harris-Kojetin, 2013). Traditionally, antipsychotic medications have been first-line treatment for NPS in ALF residents; however, they often place people with dementia at higher risk of adverse events and a poorer quality of life (Maust et al., 2015). While non-pharmacologic interventions are considered the first line of defense for NPS, few non-pharmacologic interventions have been evaluated in ALFs. For families, there are approximately 200 hundred non-pharmacologic informal caregiver support programs that have been tested in community or home based populations (Gitlin & Hodgson, 2015) but most have not been tested in the ALF setting.

The purpose of this paper is to examine nonpharmacological interventions tested in ALFs for two of the most prevalent mental health issues: depression and NPS of residents. We do this by way of a scoping review of the literature. We conclude with a discussion and a call to action for assisted living facilities and researchers to advance quality mental health care in this growing industry.

METHODS

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We searched PubMed, Embase, Medline, Psych Info, and CINAHL Plus for relevant peer reviewed publications available in English between January 1990 and February 2017. Search terms were: assisted living facilities, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive impairment, memory loss, mental illness, mental disorder, behavior, depression, resisting care, anxiety, agitation, aggression, paranoia, wandering, intervention, prevention, program, education, and training. References for review articles and meta-analyses as well as reference sections for articles identified through the search were also reviewed for any additional articles that met selection criteria.

Selection Criteria

Study inclusion criteria were: 1) study was conducted in an ALF or a similar setting as there are differences in terminology for ALF both within the United States and abroad (careful consideration was given to ensure that the settings represented in studies were similar in their approach to care); 2) study described a non-pharmacologic intervention; and 3) study reported outcomes for resident mental health, specifically depression and/or NPS. Studies did not need to be specific to residents with dementia. Studies were excluded if they were: 1) not solely based in an ALF; 2) intervention was directed toward improved memory or physical function (and not mental health); or 3) intervention was medication-based or had a medication component. We did not exclude studies based on design as our intention is to provide a comprehensive examination of the evidence base.

RESULTS

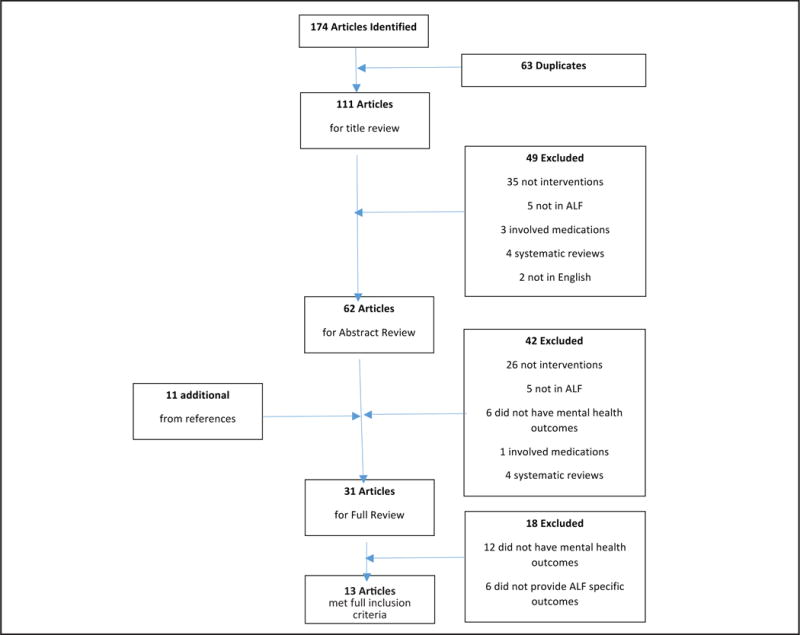

Initial results of the search yielded 111 articles after duplicates were excluded (Figure 1). A review of titles excluded 49 studies applying the above criteria, leaving 62 studies for an abstract review. Based on abstract review, 20 articles and an additional 11 articles from the review of references were retained for full article review. Three coders (KM, DS, ND) read the articles independently to determine their relevance for inclusion in the final review and then met to discuss coding differences. Thirteen articles were identified and agreed upon for inclusion in the final review (Table 1). There were two additional studies that may have met inclusion criteria but were excluded because it was unclear if the dementia unit was in an assisted living or a skilled nursing facility (Detweiler, Murphy, Myers, & Kim, 2008; Ford Murphy, Miyazaki, Detweiler, & Kim, 2010).

Figure 1.

Results of search for non-pharmacologic interventions in assisted living settings for mental health

Table 1.

Intervention Studies for Mental Health in Assisted Living Facilities

| Study | Intervention | Number of sites/Country | Number of Participants | Target population (staff/residents/environment) | Study Design | Mental health outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| (Altus & Engelman, 2002) | Activity Record with immediate feedback from facility director | 1 locked dementia unit USA | 6 residents with dementia 2 CNAs | Staff | Observation pre and post intervention | Inappropriate engagement (aggression, screaming, wandering) decreased |

| (Bauer et al., 2015) | Snoezelen® room with activity therapist | 2 Residential Adult Care Facilities Australia | 16 residents with dementia | Residents | Descriptive observational | Both Snoezelen® and common best practices both significantly reduced wandering and restlessness |

| (Brooker et al., 2011) | Enriched Opportunities Programme (EOP) | 10 Extra Care Housing schemes (5 intervention/5 control) UK | 293 residents with possible dementia | Staff | RCT | EOP residents reported significantly lower depression scores. |

| (Dozeman et al., 2012) | Stepped-care program to decrease depression and anxiety. | 14 residential homes Netherlands | 185 residents without cognitive impairment | Residents | Pragmatic RCT | Incidence of depression was significantly lower in the intervention group but there was no difference in anxiety between groups. |

| (Friedmann et al., 2014) | Animal-assisted therapy title pet-assisted living (PAL) | 7 facilities (4 intervention/3 control) USA | 40 residents with cognitive impairment | Residents | RCT | The rate of depression in the PAL intervention decreased significantly more than the control group. Apathy scores improved for the PAL group and worsened for the control group though neither change was statistically significant. |

| (Haight et al., 2006) | Structured life review with a trained interviewer | 6 facilities Northern Ireland | 30 residents with dementia | Residents | Pre-post with control group Randomization is unclear | Depression scores decreased for intervention residents and were significantly lower than controls at follow-up. |

| (Haslam et al., 2010) | Group reminiscence activities or individual reminiscence activities | 2 facilities UK | 73 residents in either assisted care or dementia care | Residents | 3-group RCT Group 1: Group Reminiscence Group 2: Individual Reminiscence Group 3: Group Activity |

Participants in the Group activity reported significantly better wellbeing (depression, life improvement, quality of life) than the group or independent reminiscence. |

| (Hsu et al., 2015) | Music therapy program | 2 care homes UK | 17 residents with dementia 10 staff | Residents and staff | Cluster RCT Feasibility | NPS and disruption scores in the music therapy group decreased and control group symptoms and disruption increased. |

| (Hutson et al., 2014) | Sonas, group intervention involving multisensory stimulation, reminiscence | 4 care homes UK | 39 residents with dementia | Residents | RCT Pilot | No statistically significant findings on neuropsychiatric scores |

| (Janata, 2012) | Customized music program | 1 facility USA | 38 residents with dementia | Residents/Environment | RCT | Decrease in NPS was seen in both groups. |

| (Lin et al., 2007) | Aroma therapy of Lavender | Care and Attention Homes (total number not reported) Hong Kong | 70 residents with dementia | Residents | Cross-over randomized | NPS decreased significantly after aroma therapy with Lavender. No significant change with sunflower. |

| (Teri et al., 2005) | STAR (Staff Training in Assisted living Residences) | Feasibility Study: 15 facilities USA Randomized Trial: 4 facilities USA |

Feasibility Study: 120 residents with dementia 114 staff Randomized Trial: 31 residents with dementia 25 staff |

Staff | Residents in the STARs group had improved scores for all behavior measures where as those in the control group either stayed the same or worsened. | |

| (Wenborn et al., 2013) | Environmental assessment Education Program One-on-one coaching sessions. |

16 care homes UK | 210 residents 52 staff | Staff | Cluster randomized control | All measures of behaviors were not statistically significant. |

The studies included were represented by six countries (United Kingdom, United States, Australia, Netherlands, Ireland, and China). Sample sizes ranged from six to 293 residents. Only four (30.8%) studies had a sample of more than 100 residents (Brooker, Argyle, Scally, & Clancy, 2011; Dozeman et al., 2012; Teri, Huda, Gibbons, Young, & van Leynseele, 2005; Wenborn et al., 2013), one of which was a feasibility study which did not report outcomes, however, the pilot portion of the study did report resident outcomes on 31 residents (Teri et al., 2005). All but two studies focused on residents with dementia; Dozeman et al. (2012) involved participants without cognitive impairment, and Wenbourn et al. (2013) included those with and without cognitive impairment.

The interventions evaluated were varied, including activity engagement (n = 3), life review or reminiscence (n = 2), music therapy (n = 2), animal-assisted therapy (n = 1), Snoezelene® (n = 1), aroma therapy (n = 1), staff training (n = 1), and some had multiple components (n = 2). Outcomes of the studies were mixed; 61.5% (n = 8) reported positive outcomes for depression or NPS whereas 38.5% (n = 5) reported null findings.

Activity Engagement

Three studies examined activity engagement (Altus & Engelman, 2002; Bauer et al., 2015; Brooker et al., 2011; Wenborn et al., 2013). Altus and Engelman (2002) studied use of an activity record—list of activities used and quality of resident engagement—completed by two staff members with immediate positive feedback from a supervisor at one facility in the United States. The primary outcome studied was inappropriate engagement (e.g. aggression, screaming, wandering) in persons with dementia. Six residents and two staff participated in the study. Staff were instructed to complete an activity record and resident level of engagement during one-hour observation periods. The facility Activity Director immediately read the records and provided positive feedback to staff. This approach resulted in a decrease in inappropriate engagement and the mean number of activities increased for each resident. Of note, results were only available at follow-up for one staff as the other was no longer with the facility.

Brooker and colleagues (2015) compared use of the Enriched Opportunities Program (EOP) to an attention control group over 18 months in 10 facilities in England. The EOP program involved a trained specialist staff (EOP Locksmith) at each site as an additional staff person. The control sites had an additional staff person to assist in care and to help improve activities. The EOP Locksmith worked with residents to identify meaningful activities for each individual. The Locksmith made sure that activities were available and were tailored to the capabilities of the resident. The EOP Locksmith also provided a one-day training in person-centered care and was available to other staff to help identify and solve problems in the management of resident behaviors. While control sites did have an extra staff person for the duration of the study, their approach was not person-centered nor did it involve tailored activities. Results showed that EOP residents reported significantly lower depression scores than control group residents.

Wenborn and colleagues (2013) studied the effects of a program designed to increase activity engagement on quality of life and NPS in persons with dementia at 16 facilities in the United Kingdom. In this cluster, a randomized study of 210 residents and 52 staff participated. Eight facilities were assigned to the intervention group and eight to the control group. The intervention consisted of an environmental assessment with recommendations for adaptations to enhance activity engagement, an education program that included five two-hour education sessions with staff, work-based learning tasks to identify meaningful activities for residents, and one-on-one coaching sessions. Results found no statistically significant improvements in any of the outcome measures.

Life Review/Reminiscence

Two studies examined life review or reminiscence as an intervention (Haight et al., 2006; Haslam et al., 2010). Haight and colleagues (2006) studied the effects of a structured life review course on depression scores in six facilities in Northern Ireland. Thirty residents participated in either an intervention (n = 15), where they created a life book through a structured life review with a trained staff member of the ALF facility over a six-week period, or a usual care control group (n = 15). Depression scores decreased for intervention residents and were significantly lower than controls at follow-up.

Haslam and colleagues (2010) studied the effects of group reminiscence or individual reminiscence at two care homes in the United Kingdom. Seventy-three residents were randomly assigned to either group reminiscence (n = 29), individual reminiscence (n = 24), or an attention control group that met to play a game (n = 20). Results show that participants in the control group reported significantly better well-being (depression, life improvement, quality of life) than either group reminiscence or independent reminiscence.

Music Therapy

Like reminiscence, the two interventions that studied music therapy had mixed outcomes (Hsu, Flowerdew, Parker, Fachner, & Odell-Miller, 2015; Janata, 2012). Hsu and colleagues (2015) studied the effect of weekly individual music therapy sessions on NPS of persons with dementia in two facilities in the United Kingdom. For this study, 17 residents and 10 staff were randomly assigned to either music therapy (n = 9) or a usual care control (n = 8). The residents in the intervention group received 1:1 music therapy for 30 minutes once a week from qualified music therapists. Four constructs utilizing auditory and visual cues were utilized during sessions; these included well-known songs, free music-making, talking, and facial or bodily expressions. After each session, video clips were shown to the staff involved in the study. The video presentations were used to show how NPS can be minimized, possible causes of symptoms, and how the therapist uses preserved capabilities to enhance participation. Results found that NPS and disruption scores in the music therapy group decreased over five months and control group symptoms and disruption increased. Care staff reported positive benefits of music therapy on their daily work, including enhanced communication and increased insight into the residents. Staff also expressed interest in learning more about music therapy to increase their self-confidence in completing the intervention with the participant.

Janata (2012) studied the effects of a customized music program for persons with dementia on agitation and depression at one facility in the United States. Residents were randomly assigned to either the music group (n = 19) or a usual care control group (n = 19). Participants in the music group had a music program designed for them by a music therapist. Music was then piped into their rooms at specific times of the day for 12 weeks. Results found a decrease in NPS for both groups. One explanation for this result is that control group participants were exposed to the music program if they were in the room of a participant in the music group.

Animal-assisted Therapy

One study evaluated animal-assisted therapy (Friedmann et al., 2014). Friedman and colleagues (2014) studied the effects of animal-assisted therapy to improve physical activity and decrease depression, apathy, and agitation in seven assisted living facilities in the United States. Pet-assisted living (PAL) involves 60–90 minute sessions of structured activities with a dog, such as feeding, brushing, throwing a ball, petting, and talking to the dog, over a 12-week period. There were 22 residents in the PAL intervention group that were compared to 18 residents in an attention-control group that participated in a reminiscence activity. The rate of depression in the PAL intervention decreased significantly more than the control group. Apathy scores improved for the PAL group and worsened for the control group, though neither change was statistically significant.

Aroma Therapy

One study examined the effects of aroma therapy on agitation in persons with dementia at facilities in Hong Kong (Lin, Chan, Ng, & Lam, 2007). In this cross-over randomized study, 70 residents were randomly assigned to either the first treatment group (n = 35) or the second treatment group (n = 35). For three weeks, the first treatment group had the essential oil lavandula angustifolia (lavender) placed in diffusers next to their bed for at least one hour each night. The control group had sunflower oil placed in diffusers next to the bed for the same time period. After three weeks, the groups switched. The study found that agitation severity decreased significantly after aroma therapy with lavender. Dysphoria, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, and nighttime behaviors also saw significant reductions. No significant change was found with the sunflower oil.

Snoezelene®

One study evaluated a dedicated Snoezelene® room in two facilities in Australia to examine the impact on wandering and restless behaviors in persons with dementia (Bauer et al., 2015). Participants in the Snoezelene® room group (n = 9) were compared to a control group (n = 7) of what the authors term as “common best practices” for managing NPS. These best practices included speaking with the resident, diversion, and distraction using activities, rest, and pain assessment. This was an observation-based study, where research nurses observed and recorded the behavior of both groups twice a week for 12 weeks. Both groups showed a statistically significant improvement in wandering and restlessness, but there was no statistically significant difference between the groups indicating that a Snoezelen® room had an advantage over the “common best practices” for managing behaviors.

Staff Training

One study focused on the feasibility and outcomes of a staff training program to reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia (Teri et al., 2005). Feasibility testing was conducted at 15 facilities in the United States with 120 residents and 114 staff, however, it reported no outcome on behavior measures. The randomized trial was conducted with 31 residents and 25 staff at four facilities in the United States (two sites were experimental and two were control). The Staff Training in Assisted Living Residences (STAR) program consists of two four-hour workshops for direct care staff, four on-site consultations, and three leadership sessions over two months in the assisted living facility. During the workshops, staff learn the basics of dementia, communication techniques, how to assess behaviors, and how to act on behaviors. Results of the randomized trial found overall NPS decreased and, specifically, depression and anxiety decreased.

Multi-component

Two studies examined multi-component interventions (Dozeman et al., 2012; Hutson, Orrell, Dugmore, & Spector, 2014). Dozeman and colleagues (2012) studied the effects of a stepped program on depression and anxiety in residents of 14 facilities in the Netherlands. The four-step program included: (1) Watchful Waiting; (2) Activity-scheduling; (3) Life Review and consultation with general practitioner; and (4) Visit to general practitioner for additional treatment. Residents with a CES-D score of eight or greater were invited to participate. After three months, they were re-evaluated and if the CES-D score had not changed meaningfully (decrease of at least five points), then they were invited to the next level for the next three months. A total of 185 residents participated; 93 were randomly assigned to the step intervention and 92 to usual care. Results found that the incidence of depression was significantly lower in the intervention group but there was no difference in anxiety between groups.

Hutson and colleagues (2014) studied the effects of Sonas, an intervention that involved multisensory stimulation, reminiscence, and gentle physical activity, in four facilities in the United Kingdom on quality of life and NPS in persons with dementia. Thirty-nine residents of the homes were randomly assigned to either the Sonas intervention group (n = 21) or usual care (n = 18). The Sonas group received 14 sessions over a seven to eight week period, with each session lasting approximately 45 minutes. Results found no statistically significant findings on neuropsychiatric scores between the two groups. Of note in this study is that 80.6% of participants were in the severe dementia stage.

DISCUSSION

This paper examines non-pharmacologic interventions for mental health issues that have been tested in the ALF setting. Our review of the research literature yielded 13 published peer-reviewed studies that examined non-pharmacologic interventions for mental health in this setting. Most of the research on mental health care has been community-based or in nursing homes. Some studies have included ALFs, however they combine ALF and nursing home residents in analyses despite contextual differences in settings. We argue that this is a mistake as ALFs and ALF residents have different characteristics than residents in nursing homes. The basic philosophic design of ALF communities also differs from nursing homes, with ALFs embracing a social model whereas nursing homes are built upon a medical model (Zimmerman et al., 2003). As such, ALF residents are often higher functioning and require less care, resulting in a higher staff to resident ratio in this setting (Teri et al., 2005).

The studies included in our review showed mixed results concerning 13 distinct interventions to address mental health issues that were evaluated with assisted living residents. However, all of the 13 studies reviewed had significant methodological limitations, first of which is sample size. Only three studies reporting resident outcomes had a sample of more than 100 residents. Some studies had as few as six resident participants and most studies involved a single site, making generalizability questionable. A second limitation is that only two studies included residents that were not cognitively impaired. While the evidence for the interventions with persons with dementia is limited by scope and design, the evidence for those without cognitive impairment is even more so. A third limitation is the lack of replication of interventions. Aroma therapy and pet-assisted therapy both had significant outcomes but only one study of each was conducted in the assisted living setting. Teri et al. (2009) completed the STAR training with staff from additional facilities, however, they have not published additional resident outcome data. Fourth, most of the interventions are not person-centered. The philosophy of person-centered care is one of the things that sets ALF apart from other forms of seniors housing. The music therapy (Hsu et al., 2015; Janata, 2012) and activity engagement (Brooker et al., 2011; Wenborn et al., 2013) interventions had some individualization. The one music program (Janata, 2012) found that both the experiment and control group improved, however it may have been due to the fact that control residents were exposed to the intervention. Finally, there is a lack of long-term evidence of beneficial outcomes for any of the interventions. Altus and Engelman (2002) noted that one reason might be that trainings and interventions may not continue after the study has concluded.

In a systematic review of non-pharmacologic interventions to reduce agitation and aggression in persons with dementia, Jutkowitz et al. (2016) found insufficient evidence to show that the interventions were better than usual care in assisted living and nursing homes. This review examined 19 studies, only one of which was completed solely in an assisted living facility. The other 18 studies were in nursing homes or in a combination of the two types of facilities. This review (Jutkowitz et al., 2016) had very strict inclusion criteria. For example, all studies included were randomized controlled trials. Our findings are similar although we used less stringent criteria for this review in order to include any studies conducted exclusively in ALFs.

The dearth of studies in ALFs for non-pharmacologic interventions for mental health also does not show overwhelming evidence of significant benefit. It does, however, provide some evidence that certain approaches are more promising than others, which should be encouraging to facility administrators and researchers to continue to investigate in these areas. Activity engagement was found in two of three studies to have positive outcomes on NPS (Altus & Engelman, 2002; Brooker et al., 2011), and a third study that investigated reminiscence found the activity group to have more positive outcomes (Haslam et al., 2010). The one activity-based study (Hutson et al., 2014) that did not have positive outcomes was hampered by issues of fidelity and lack of staff training. Staff skipped trainings and those that were trained found it difficult to implement with any consistency. Another area that may be promising is music therapy. Hsu and colleagues (2015) found not only did resident behaviors decrease with music therapy, the therapy sessions served as training for staff in important concepts such as communication and visual cues.

Based on our review of the literature, we offer several recommendations and actions for ALFs concerning non-pharmacologic interventions for mental health (Table 2). First, while there has been very little research specifically in the ALF setting, we recommend that ALFs adopt evidence-based or evidence-informed non-pharmacologic interventions for managing NPS. This review found some evidence to point toward the use of activity or music-based interventions, especially those that are person-centered, to reduce NPS. Second, we recommend the use of activity as a therapeutic modality (Gitlin et al., 2016). Activity engagement, including music, can be utilized by staff to interact effectively with residents. This is particularly true if the activity meets the resident at his/her current capabilities and draws on their prior roles and interests (Gitlin et al., 2016). Third is to adopt new training approaches. A concern in current training is the lack of evidence-based trainings and evidence-based approaches to mental health care in assisted living facilities. Teri and colleagues (2009) have the only published evidence-based training for ALF staff and showed positive outcomes. Implementation of the training into additional facilities has been difficult. As Teri and colleagues (2009) found in scaling up their training, time and job pressures are barriers to training staff. Wenborn and colleagues (2013) also had issues with staff attending trainings in their study and it may have affected the outcomes. Trainings need to be adapted to better suit adult learners and at the same time not take much time away from facilities. One way this can be done is through hands-on-training approaches that use peer leaders as trainers. A fourth recommendation is to utilize emerging technologies for trainings and interventions. Trainings can be partially on-line, allowing staff to work at their own pace through trainings. On-line and application interventions are becoming more mainstream and may assist ALF in providing care in the moment. Fifth, considering the current lack of research on evidence-based interventions for residents and trainings for staff, we need to continue to work toward development and testing of new interventions. One way to do this is for ALFs to participate in and publish more practice-based research. There are many interventions that have been tested in the community or nursing homes that could be adapted to the ALF setting. However, when introducing the intervention, careful consideration of the interventions key components should be investigated by the ALF. Additionally, ALFs should note any alterations made for this setting. Additionally, have measurable outcomes for any new intervention. These outcomes will help the facility and also in the field. A second way to advance interventions is for ALFs to partner with researchers and form collaborative relationships. It is important that representatives of all key stakeholders be included when interventions are being developed. Interventions take place within a facility and things such as daily work load, staffing patterns, and environment need to be taken into consideration during development (Gitlin & Czaja, 2016). The more input from facilities at the development stage, the more likely a successful intervention will be continued beyond the study duration. ALFs, in turn, can rely on the expertise of researchers to assist in the development and especially the evaluation of interventions and trainings.

Table 2.

Recommendations for Use of Evidence-based Non-pharmacologic Interventions to Address Mental Health Issues of Residents Living in ALFs

| Recommendation | Action Items |

|---|---|

| 1. Adopt evidence-based or evidence-informed interventions |

|

| 2. Use tailored activity as a therapeutic modality |

|

| 3. Adopt new training approaches |

|

| 4. Use emerging technologies for training and intervention |

|

| 5. Participate in practice-based research |

|

There are several limitations to this study. Every attempt was made to include all studies that have been conducted and reported results on ALF. However, multiple terms were found that referred to ALFs, including “residential care home,” “care and support homes,” “chronic care facilities,” “aged care facility,” “sheltered housing,” and “housing with care.” There may be others that were not identified and therefore were not included. Additionally, the regulations and environments of ALFs vary from state to state in the United States. This makes it difficult, but not impossible, to study and implement interventions and trainings across multiple states. Careful consideration needs take place at the development phase of interventions to overcome this limitation.

CONCLUSION

Mental health issues are highly prevalent among ALF residents, especially depression and NPS. Mental health issues are a concern to all stakeholders, residents’ families, staff and administrators, and have pernicious consequences including burnout and turnover.

Research on programs to help formal and informal caregivers care for people with dementia have primarily been based either in the community or nursing home. There are few interventions that have been developed for and tested in ALFs, and prior literature reviews typically group ALFs with nursing homes in the assessment of the overall effect of programs. There are differences that exist between ALFs and nursing homes, such as staffing ratios and resident level of dependence, and philosophical foundations that suggest the need for research dedicated to the ALF setting. The studies that have been conducted show some promising results with activity engagement and music therapy. ALFs have an opportunity to address mental health issues by incorporating evidence-based interventions into their facilities and by working with researchers to develop new interventions tailored for delivery in this type of facility.

Acknowledgments

Grant number P30 AG048773

Contributor Information

Katherine A. Marx, Research Associate, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing.

Naomi Duffort, Research Assistant, Center for Innovative Care in Aging, Johns Hopkins School for Nursing, 525 North Wolfe Street, Suite 472-I, Baltimore, MD 21205.

Daniel L. Scerpella, Research Assistant, Center for Innovative Care in Aging, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, 525 N. Wolfe Street, Suite 472-K, Baltimore, MD 21205

Quincy Miles Samus, Associate Professor Director of the Translational Aging, Services Core Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Core Faculty/Johns, Hopkins Center for Innovations in Aging, 5300 Alpha Commons Drive, 4th Floor, Baltimore, MD 21224.

Laura N. Gitlin, Director & Professor, Center for Innovative Care in Aging, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, Department of Community-Public Health, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry (Joint Appointment), 525 N. Wolfe Street, Suite 316, Baltimore, MD 21205.

References

- Altus DE, Engelman KK. Finding a practical method to increase engagement of residents on a dementia care unit. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2002;17(4):245–248. doi: 10.1177/153331750201700402. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed8&NEWS=N&AN=34857821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, Rayner JA, Tang J, Koch S, While C, O’Keefe F. An evaluation of Snoezelen® compared to “common best practice” for allaying the symptoms of wandering and restlessness among residents with dementia in aged care facilities. Geriatric Nursing. 2015;36(6):462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Draper B, Low LF. Nursing home staff attitudes towards residents with dementia: Strain and satisfaction with work. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;44(6):583–590. doi: 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker D, Argyle E, Scally AJ, Clancy D. The Enriched Opportunities Programme for People With Dementia: a Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial in 10 Extra Care Housing Schemes. Aging and Mental Health. 2011;15:37–41. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.583628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey C, Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M. Variation in Operating Characteristics of Residenital Care Communities, by Size of Community: United States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief, (222) 2015 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db222.pdf. [PubMed]

- Choi J, Flynn L, Aiken LH. Nursing practice environment and registered nurses’ job satisfaction in nursing homes. The Gerontologist. 2012;52(4):484–92. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detweiler MB, Murphy PF, Myers LC, Kim KY. Does a Wander Garden Influence Inappropriate Behaviors in Dementia Residents? American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias. 2008;23(1):32–45. doi: 10.1177/1533317507309799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozeman E, van Marwijk HW, van Schaik DJ, Smit F, Stek ML, van der Horst HE, Beekman AT. Contradictory effects for prevention of depression and anxiety in residents in homes for the elderly: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. International Psychogeriatrics. 2012;24(8):1242–1251. doi: 10.1017/s1041610212000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford Murphy P, Miyazaki Y, Detweiler MB, Kim KY. Longitudinal analysis of differential effects on agitation of a therapeutic wander garden for dementia patients based on ambulation ability. Dementia. 2010;9:355–373. doi: 10.1177/1471301210375336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann E, Galik E, Thomas SA, Hall PS, Chung SY, McCune S. Evaluation of a pet-assisted living intervention for improving functional status in assisted living residents with mild to moderate cognitive impairment: A pilot study. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2014;30(3):1–13. doi: 10.1177/1533317514545477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Czaja SJ. Behavioral intervention research: Designing, evaluating and implementing. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Hodgson N. Caregivers as therapeutic agents in dementia care: The evidence-base for interventions supporting their role. In: Gaugler J, Kane R, editors. Family Caregiving in the New Normal. Boston, MA: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 305–353. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Piersol CV, Hodgson N, Marx K, Roth DL, Johnston D, Lyketsos CG. Reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia and associated burden in family caregivers using tailored activities: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2016;49:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber-Baldini AL, Boustani M, Sloane PD, Zimmerman S. Behavioral symptoms in residential care/assisted living facilities: Prevalence, risk factors, and medication management. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(10):1610–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight BK, Gibson F, Michel Y. The Northern Ireland life review/life storybook project for people with dementia. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2006;2(1):56–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C, Haslam SA, Jetten J, Bevins A, Ravenscroft S, Tonks J. The social treatment: The benefits of group interventions in residential care setting. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25(1):157–167. doi: 10.1037/a0018256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu MH, Flowerdew R, Parker M, Fachner J, Odell-Miller H. Individual music therapy for managing neuropsychiatric symptoms for people with dementia and their carers: a cluster randomised controlled feasibility study. BMC Geriatrics. 2015;15(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0082-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson C, Orrell M, Dugmore O, Spector A. Sonas: a pilot study investigating the effectiveness of an intervention for people with moderate to severe dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias. 2014;29(8):696–703. doi: 10.1177/1533317514534756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janata P. Effects of Widespread and Frequent Personalized Music Programming on Agitation and Depression in Assisted Living Facility Residents with Alzheimer-Type Dementia. Music and Medicine. 2012;4(1):8–15. doi: 10.1177/19438621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jutkowitz E, Brasure M, Fuchs E, Shippee T, Kane RA, Fink HA, Kane RL. Care-Delivery Interventions to Manage Agitation and Aggression in Dementia Nursing Home and Assisted Living Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016;64(3):477–488. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PW, Chan W, Ng BF, Lam LC. Efficacy of aromatherapy (Lavandula angustifolia) as an intervention for agitated behavious in Chinese older persons with dementia: a cross-over randomized trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:405–410. doi: 10.1002/gps.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Carrillo MC, Ryan JM, Khachaturian AS, Trzepacz P, Amatniek J, Miller DS. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2012;7(5):532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maust DT, Kim HM, Seyfried LS, Chiang C, Kavanagh J, Schneider LS, Kales HC. Antipsychotics, other psychotropics, and the risk of death in patients with dementia: number needed to harm. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;48109(5):1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, Tachimori H, Ito H. Formal Caregiver Burden in Dementia: Impact of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia and Activities of Daily Living. Geriatric Nursing. 2010;31(4):246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park-Lee E, Sengupta M, Harris-Kojetin LD. Dementia special care units in residential care communities: United States, 2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(134):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt A, Samus QM, Steele CD, Baker AS, Harper MG, Brandt J, Lyketsos CG. The Maryland Assisted Living Study: Prevalence, Recognition, and Treatment of Dementia and Other Psychiatric Disorders in the Assisted Living Population of Central Maryland. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(10):1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz D, Purandare N, Conn D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2010;22(7):1025–1039. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Huda P, Gibbons L, Young H, van Leynseele J. STAR: A dementia-specific training program for staff in assisted living residences. The Gerontologist. 2005;45(5):686–693. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LC, Lehmann S, Mayer L, Samus Q, Baker A, Brandt J, Lyketsos C. Depression in assisted living is common and related to physical burden. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(10):876–883. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000218698.80152.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenborn J, Challis D, Head J, Miranda-Castillo C, Popham C, Thakur R, Orrell M. Providing activity for people with dementia in care homes: A cluster randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;28(12):1296–1304. doi: 10.1002/gps.3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Gruber-Baldini AL, Sloane PD, Eckert JK, Hebel JR, Morgan LA, Konrad TR. Assisted living and nursing homes: apples and oranges? Gerontologist, 43 Spec No(Ii) 2003:107–117. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Reed D. Dementia prevalence and care in assisted living. Health Affairs. 2014;33(4):658–666. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwijsen SA, Kabboord A, Eefsting JA, Hertogh CMPM, Pot AM, Gerritsen DL, Smalbrugge M. Nurses in distress? An explorative study into the relation between distress and individual neuropsychiatric symptoms of people with dementia in nursing homes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;29(4):384–391. doi: 10.1002/gps.4014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]