Abstract

Objective

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) studies in systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients of European American (EA) ancestry have identified variants in the ATP8B4 gene and enrichment of variants in genes in the extracellular matrix (ECM)-related pathway increasing SSc susceptibility. Our goal was to evaluate the association of the ATP8B4 gene and the ECM-related pathway with SSc in a cohort of African Americans (AA).

Methods

SSc patients of AA ancestry were enrolled from 23 academic centers across the United States under the Genome Research in African American Scleroderma Patients (GRASP) consortium. Unrelated AA individuals without serological evidence of autoimmunity enrolled in the Howard University Family Study were used as unaffected controls. Functional variants in genes reported in the two WES studies in EA SSc were selected for gene association testing using the optimized sequence kernel association test (SKAT-O) and pathway analysis by Ingenuity pathway analysis in 379 patients and 411 controls.

Results

Principal components analysis demonstrated that the patients and controls had similar ancestral backgrounds with about equal proportions of mean European admixture. Using SKAT-O, we examined the association of individual genes that were previously reported in EAs, and none remained significant including ATP8B4 (PUnCorr=0.98). However, we confirm the previously reported association of the ECM-related pathway with enrichment of variants within the COL13A1, COL18A1, COL22A1, COL4A3, COL4A4, COL5A2, PROK1, and SERPINE1 genes (PCorr=1.95×10−4).

Conclusion

This is the largest genetic study in AAs with SSc to date, corroborating the role of functional variants aggregating in a fibrotic pathway and increasing SSc susceptibility.

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) or scleroderma is a chronic multisystem disease, which is characterized by fibrosis of the skin and internal organs, a systemic vasculopathy, and autoimmunity. Compared with European Americans (EA), African Americans (AA) have a higher incidence and prevalence of SSc in the United States (1). Compared to EAs, SSc in AAs occurs at an earlier age and is more likely to be manifested by diffuse skin involvement, and the presence of anti-topoisomerase I (ATA) or anti-fibrillarin (AFA) antibodies; features that associate with severe disease and a worse outcome (2). AAs are more likely to develop severe interstitial lung disease (ILD) or pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). This lung disease accounts for the major overall SSc-related deaths in all racial groups (3).

The etiology of SSc is unknown but several environmental agents and genetic variants have been implicated. A strong role for genetic etiological factors has been suggested in SSc by family studies showing an absolute risk of 1.6% in families as compared to 0.026% in the general population (4). Candidate gene, family-based, and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) looking at common variants, conducted mostly in EA SSc, have revealed autoimmune disease susceptibility loci that are not unique to SSc (5). These studies focused on common variants that have only been able to partially account for SSc heritability. Rare variants (minor allele frequency (MAF)<0.5%) and low frequency variants (MAF 0.5–5%) have recently been implicated in several diseases and could account for a portion of the missing SSc heritability.

Recent reports suggest an increased burden of rare coding variants in genes and pathways in complex diseases beyond the common variants identified by GWASs. Various techniques used to identify genes with aggregation of deleterious variants include candidate gene Sanger sequencing for a hypothesis-driven approach. Next generation sequencing platforms including whole-exome sequencing (WES) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) provide hypothesis-neutral approaches. Gao et al recently performed WES in 78 EA SSc patients and found an enrichment in functional ATP8B4 variants as compared to controls (P=2.77×10−7) (6). Furthermore, a single missense variant (rs55687265) was associated with SSc (P=9.35×10−10) and on removing this variant the ATP8B4 gene-based association was eliminated. Mak et al performed WES in 32 EA SSc, identifying 70 genes enriched with deleterious variants in the diffuse skin subset of SSc and reported significant enrichment of variants in the COL4A3, COL4A4, COL5A2, COL13A1, and COL22A1 genes in the extracellular matrix (ECM)-related pathway (P=0.002) (7). Given the potential importance of the findings of these prior smaller WES studies in EA SSc individuals, we investigated their significance in a larger cohort of AA patients with SSc by performing WES gene and pathway-based association testing.

Our understanding of genetic susceptibility in AA SSc is limited and restricted to human leukocyte antigens (HLA), due to the lack of extensive studies in the AA population (8). The Genome Research in African American Scleroderma Patients (GRASP) consortium was created to assemble a large cohort of AA patients with SSc to conduct systematic and comprehensive genetic studies. 400 AA patients with SSc and 482 controls have undergone WES and select genes from the WES analysis are being replicated in an independent series for confirmation. Herein we present the results for gene-level associations and pathway associations for genes that were previously reported in WES studies of 76 EA SSc by Gao et al and 32 EA SSc by Mak et al (6, 7). We replicated a collective enrichment of coding and deleterious variants in genes of the fibrotic pathway in AA patients with SSc.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study population

AA patients with SSc were enrolled under the GRASP consortium from 23 academic centers in the United States (Supplementary Table 1). Enrolled patients self-identified as African Americans. All patients met the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or 2013 ACR/EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) classification criteria for systemic sclerosis or had at least 3 of 5 features of the CREST syndrome (9–11). Control samples were obtained from the Howard University Family Study, a population-based study of AA families and unrelated individuals enrolled in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area (12). We included only unrelated individuals as controls in this study. Sera obtained from controls were tested for anti-nuclear antibody by indirect immunofluorescence and only those with a titer <1:80 were included in this study. DNA was extracted from whole blood samples or saliva samples.

Sequence analysis

WES was performed on 400 SSc and 482 control samples using the SeqCap EZ Exome+UTR (Roche) and libraries were sequenced on the HiSeq 2000 platform (Illumina) using 2 × 100 bp paired-end reads. Multiple variant and sample quality control filters were used prior to analyses (Supplementary Methods).

Identity by Descent Analysis, Admixture Analysis, and Principal Components Analysis

Identity by descent analysis was performed using common variants (MAF>5%) from the sequence data after linkage disequilibrium (LD) pruning (r2<0.5) for estimating kinship coefficients. To remove familial relatedness, only one sample with the highest call rate was included from individuals with pi-hat >0.085. We used the program ADMIXTURE and the 1000 genome populations as reference to estimate population admixture in our patients and controls (13). Principal components analysis (PCA) was used to estimate population stratification. A set of 35,280 markers (LD pruned (r2<0.5) and MAF>5%) were used to compute principal components (PC) and the top ten principal component eigenvalues were used to correct for population stratification using SNP & Variation Suite v8.7.1 from Golden Helix (SVS). Samples that clustered within the European cluster were removed from the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Gene-level testing was done using Optimized Sequence Kernel Association Testing (SKAT-O) with Madsen and Browning marker weighting and corrected for ancestry using the top ten PCs. Functional (missense, nonsense, and splice site) variants with a MAF<0.05 present on 20 candidate genes as reported in the Gao et al study and functional variants of all frequencies present on 87 genes from the diffuse skin disease and ILD subsets of SSc analysis from the Mak et al study were examined for association in the GRASP cohort (Supplementary Figure 1) (6, 7). To account for multiple gene testing, Bonferroni correction was applied for the total number of tests performed (20 for Gao et al and 87 for Mak et al) giving a p-value significance threshold of 0.0025 and 0.00057 respectively (6, 7). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software was used for identifying canonical pathways with all of the reported genes in the Gao et al and Mak et al studies (6, 7). Right tailed Fisher’s exact test p-values were generated for pathways and were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate correction.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

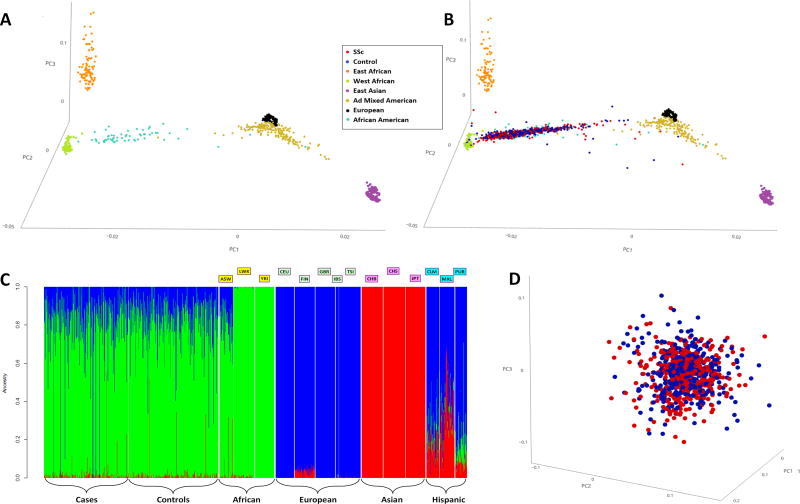

2.17% of the controls were ANA positive at ≥ 1:80 titer and were excluded. The number of females was higher in the SSc patients as compared to the controls, as expected (Table 1). The details of the sociodemographic, clinical, and serological characteristics of the GRASP cohort have been published by Morgan et al and only some of the pertinent clinical and serological data are being presented here (11). To address population stratification, we performed PCA and PC plots showed that the patients and controls in the GRASP cohort were well matched and that there was no major stratification at a global genomic level (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figures 2 and 3).

Table 1. Clinical and serologic characteristics of African American patients with systemic sclerosis and healthy controls.

| Systemic Sclerosis N (%) |

Controls N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 64 (16.9%) | 217 (52.8%) |

| Female | 315 (83.1%) | 194 (47.2%) |

| Skin involvement | ||

| Limited SSc | 166 (43.8%) | |

| Diffuse SSc | 188 (49.6%) | |

| Autoantibodies | ||

| Anti-centromere | 44 (11.6%) | |

| Anti-topoisomerase I | 107 (28.2%) | |

| Pulmonary Arterial Hypertensiona | 73 (19.3%) | |

| Interstitial Lung Diseaseb | 114 (30.1%) |

Pulmonary arterial hypertension on right heart catheterization

Pulmonary fibrosis on computed tomography of chest

Figure 1. 1A, 3D Principal Component Analysis plotting the 1000 genomes populations; 1B, 3D Principal Component Analysis plotting the 1000 genomes populations along with the SSc cases and controls; 1C, Admixture plot of the SSc cases and controls along with the 1000 genomes populations; and 1D, 3D principal component analysis plotting the SSc cases and controls.

1A, 1B: Each dot represents an individual. Red- SSc cases; Blue- Controls; Gold- Ad Mixed American:CLM, MXL, PUR; Light Blue- African American; Orange- East African: LWK; Purple- East Asian:CBB, CHS, JPT; Black- European:CEU,FIN,GBR,IBS,TSI; Light Green- West African:YRI. Principal component analysis shown with the top 3 principal components.

1C: Each individual is represented as a vertical bar. The Y-axis depicts contributions from the African (Green), European (Blue), and Asian (Red) ancestries. The cases and controls look very similar to each other and similar to the ASW from the 1000 genomes project.

1000 genomes populations: ASW-Americans of African Ancestry in SW USA, LWK-Luhya in Webuye, Kenya, YRI-Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria, CEU-Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry, FIN-Finnish in Finland, GBR-British in England and Scotland, IBS-Iberian Population in Spain, TSI-Toscani in Italia, CHB-Han Chinese in Beijing, China, CHS-Southern Han Chinese, JPT-Japanese in Tokyo, Japan, CLM-Colombians from Medellin, Colombia, MXL-Mexican Ancestry from Los Angeles USA, PUR-Puerto Ricans from Puerto Rico.

1D: Red- SSc cases; Blue- Controls. Each dot represents an individual. Principal component analysis shown with the top 3 principal components.

Sequence Analysis

A total of 400 SSc and 482 control exomes were sequenced using the same platform and analyzed simultaneously. After quality control filtering, 379 SSc cases and 411 controls remained and were used for further analysis (Supplementary Methods). An average of 90% of targeted bases produced high-confidence calls and mean depth of coverage was 47× in the targeted region. The Ti/Tv ratio for the coding region was 3.29 and the ratio for heterozygous to non-reference homozygous variants was 2.6.

PCA was performed for fine characterization of genetic ancestry. A 3D PCA plot depicted the AAs to be spread between the West African and European clusters based on their degree of European admixture (Figures 1A, 1B and Supplementary Figures 2, 3). The GRASP samples were closer to the West African cluster and distinct from the East African cluster, confirming West Africa as the main ancestral home of AAs. The admixture proportions in GRASP samples were similar to those of AAs in the 1000 Genomes Project (ASW-Americans of African Ancestry in SW USA) with major contributions from West African and European ancestries and a minor contribution from the Asian ancestry, likely representing Native American admixture (Figures 1B, 1C and Supplementary Figures 2, 3). The amount of average individual European admixture with mean (SD) in the SSc samples was 16.98% (12.4%) and the mean (SD) in controls was 16.52% (11.7%) and was not statistically different (t-test p-value=0.59) (Supplementary Figure 4). The admixture plot also confirmed that the patients and controls are ancestrally very similar to each other (Figure 1D).

Gene-level analysis

All variants in the 20 genes, as described in the Gao et al manuscript, were included for gene-level testing using SKAT-O with the top 10 PCs as covariates (6). The ATP8B4 gene-level association reported in EAs did not reach statistical significance in the GRASP cohort (P=0.98) (Supplementary Table 2 and 3). A missense variant (rs55687265) found by Gao et al to be the primary signal for association in the ATP8B4 gene had similar frequency in the SSc patients and controls and was not statistically significant in the GRASP cohort (PUnCorr=0.84; Supplementary Table 4) (6).

We used SKAT-O to examine the 87 unique genes reported in the Mak et al study in the GRASP cohort. The COL4A4 gene had a PUnCorr=0.038 and after correcting for multiple testing was not significant (Supplementary Table 5) (7). On examining the diffuse skin disease subset of SSc patients we found the MSR1 gene that had a PUncorr=0.01 and upon examining the ILD positive subset of SSc patients the ZNF492 gene with a PUncorr=0.01, the FOLR3 gene with a PUncorr=0.03 and the STAB1 gene with a PUncorr=0.04 were identified. After correcting for multiple testing these associations were found to be statistically not significant (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). The Growth Differentiation Factor 2 (GDF2) gene was reported to have a potential enrichment of variants in GDF2 gene in the Mak et al study by burden ratio and an uncorrected P=0.00029 in the Gao et al study but was found to be statistically not significant after multiple testing correction in the GRASP cohort (PUncorr=0.04, Supplementary Table 2) (6, 7).

Pathway-based analysis

We used IPA to predict pathways enriched with gene-variants. Gene-level association results from the SKAT-O analysis in all SSc patients of the 20 genes from the Gao et al study and 87 genes from the Mak et al study were used for pathway prediction (6, 7). None of the pathways predicted based on the gene list from the Gao et al study were statistically significant after multiple testing correction (6). The Hepatic fibrosis/Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation pathway identified by IPA based on the gene list in the Mak et al study comprised not only the COL13A1, COL22A1, COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL5A2 genes identified by Mak et al, but additionally included the COL18A1, PROK1, and SERPINE1 genes belonging to the same pathway (Supplementary Table 8) (7). This was the only pathway that was statistically significant in the GRASP cohort after multiple testing correction (PCorr=1.95×10−4, Table 2). The Hepatic fibrosis/Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation pathway was the only significant pathway after multiple testing correction in the diffuse subset of SSc patients (Table 2).

Table 2. Pathway Analysis of the candidate genes in the GRASP cohort.

Ingenuity Pathway analysis depicting the top five pathways on exploring the 87 genes reported in Mak et al (7) study using the SKAT-O method in all SSc and diffuse subset of SSc patients. The Ingenuity Pathway Analysis program was used for predicting pathways. P-values were calculated using a right-tailed Fisher’s exact test. P-values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

| Ingenuity Pathway | PUnCorr | PCorr |

|---|---|---|

| All SSc patients as compared to controls | ||

| Hepatic Fibrosis / Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation | 2.09 × 10−6 | 1.95 × 10−4 |

| Melatonin Degradation III | 0.005 | 0.22 |

| Coagulation System | 0.01 | 0.29 |

| Complement System | 0.01 | 0.29 |

| Atherosclerosis Signaling | 0.02 | 0.34 |

| Diffuse subset of SSc patients as compared to controls | ||

| Hepatic Fibrosis / Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation | 2.27 × 10−6 | 2.14 × 10−4 |

| Melatonin Degradation III | 0.005 | 0.22 |

| Coagulation System | 0.01 | 0.29 |

| Complement System | 0.01 | 0.29 |

| Atherosclerosis Signaling | 0.02 | 0.36 |

PUnCorr Right-tailed Fisher’s exact p-value

PCorr Multiple test-corrected P-values using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction

Discussion

In this large cohort of AA patients with SSc, we examined the 20 candidate genes reported by Gao et al and the 87 candidate genes reported by Mak et al in their recent WES studies conducted in EA SSc (6, 7). We failed to replicate the ATP8B4 gene association or the rs55687265 variant in the ATP8B4 gene despite having a much larger sample size than the original studies. We were able to replicate the association with the ECM-related pathway, but found no additional associations. A major accomplishment of this investigation is the establishment of the GRASP cohort comprising a large sample of AA patients with SSc and controls with similar ancestral backgrounds. The GRASP cohort will serve as a valuable resource for future transethnic genomic studies in SSc.

Pathway analysis in the GRASP cohort based on the genes reported by Mak et al highlighted a fibrotic pathway that had enrichment of genes with functional variants involved in ECM biology (7). The gene list included several genes in the collagen family and genes involved in fibrinolysis and angiogenesis. The clustering of these genes into a fibrosis network corresponds to the excessive synthesis and deposition of ECM proteins observed in SSc and thus could be a potential candidate for targeted therapy. The GDF2 (also known as Bone Morphogenetic Protein 9, BMP9) gene that was studied in our current paper and identified in the Gao et al and Mak et al studies did not reach statistical significance after multiple testing correction, but remains an interesting candidate gene involved in modulation of the ECM (6, 7).

In the GRASP cohort, AA patients as well as the controls primarily derived their ancestry from West Africa and on average had similar proportions of African, European and Asian (likely Native American) ancestries. The patients and controls were recruited from different geographic locations in the US, and using PCA and the ADMIXTURE program we were able to demonstrate that there was no major population stratification between the patients and controls.

Ancestry-specific associations have previously been identified in complex diseases. Similar to the PADI4 gene association in Asians and the PTPN22 gene association in Europeans with rheumatoid arthritis, it may be the case that there are differences in SSc susceptibility loci in different ancestral populations (14). The AA population is a recently admixed population and as we have demonstrated contain varying amounts of European and Asian ancestries. This difference in genetic architecture could explain the lack of association of the ATP8B4 gene and the rs55687265 variant in AA patients with SSc. In the original report of rs55687265 variant association with EA scleroderma by Gao et al, the discovery set contained 78 patients with a P=9.35×10−10; OR 6.11 and the replication set had 415 patients with a P=0.01; OR 1.86 (6). Nevertheless, a recent study using 7,426 SSc patients and 13,087 controls of European ancestry also was unable to replicate the rs55687265 variant (15). This underscores the importance of replication in genetics studies in large well established cohorts to demonstrate reproducibility, provide a better estimate of effect size and confirm that the original association is not due to unidentified biases present in a single study. We expect that upon completion of the GRASP targeted resequencing and final analysis of approximately 400 genes, that at least a few of these genes will be statistically significant and increase our understanding of molecular pathways involved in SSc pathogenesis.

This study corroborates the association of the ECM-related pathway in AA patients with SSc and demonstrates enrichment of shared genes in the European and African ancestral populations that increase susceptibility to SSc.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kalpana Manthiram for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding: The GRASP consortium was supported by research funding from the Scleroderma Research Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Intramural Research Programs, including the Intramural Research Programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

This study used the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster (https://hpc.nih.gov/).

Dr Pravitt Gourh has received the Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award. Dr Nadia Morgan was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number T32AR048522 and the Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award. Dr Ami Shah was supported by NIAMS of the NIH under Award Number K23AR061439. Dr Maureen Mayes was supported by grants from NIAMS of the NIH Centers of Research Translation P50-AR054144, NIH grant N01-AR-02251 and R01-AR-055258; and the Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program W81XWH-07–1–011 and WX81XWH-13–1-0452. Dr Paula Ramos was supported by grants from the NIH K01 AR067280, R03 AR065801, P60 AR062755, and the South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute, with an academic home at the Medical University of South Carolina, through NIH Grants numbers UL1 RR029882 and UL1 TR000062. Dr Richard Silver was supported by grants from the NIH P60 AR062755 and the South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute, with an academic home at the Medical University of South Carolina, through NIH Grants numbers UL1 RR029882 and UL1 TR000062. Dr Dinesh Khanna was supported by grants from NIAMS of the NIH K24 AR063120, has received investigator-initiated grants and acts as a consultant to Actelion, BMS, Bayer, Corbus, Cytori, ChemoMab, Eicos, GSK, Genentech/Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB. Dr Victoria Shanmugam was supported by grant from NIH under award number R01NR013888 from the National Institute of Nursing Research, research funding from AbbVie Pharmaceuticals, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and Scleroderma Research Foundation. Dr Chris Derk was supported by research funding from Gilead, Actelion and Cytori. Dr Francesco Boin was supported by research funding from Nina Ireland Program for Lung Health.

The sequence data shown in this study is accessible from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number SRP140756.

References

- 1.Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Jr, Beebe-Dimmer J, Gillespie BW, Cooper B, Laing TJ, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in a large US population. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2003;48(8):2246–55. doi: 10.1002/art.11073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ioannidis JP, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Haidich AB, Medsger TA, Jr, Lucas M, Michet CJ, et al. Mortality in systemic sclerosis: an international meta-analysis of individual patient data. The American journal of medicine. 2005;118(1):2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poudel DR, Jayakumar D, Danve A, Sehra ST, Derk CT. Determinants of mortality in systemic sclerosis: a focused review. Rheumatology international. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3826-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnett FC, Cho M, Chatterjee S, Aguilar MB, Reveille JD, Mayes MD. Familial occurrence frequencies and relative risks for systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) in three United States cohorts. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2001;44(6):1359–62. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1359::AID-ART228>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radstake TR, Gorlova O, Rueda B, Martin JE, Alizadeh BZ, Palomino-Morales R, et al. Genome-wide association study of systemic sclerosis identifies CD247 as a new susceptibility locus. Nat Genet. 2010;42(5):426–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao L, Emond MJ, Louie T, Cheadle C, Berger AE, Rafaels N, et al. Identification of Rare Variants in ATP8B4 as a Risk Factor for Systemic Sclerosis by Whole-Exome Sequencing. Arthritis & rheumatology. 2016;68(1):191–200. doi: 10.1002/art.39449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mak AC, Tang PL, Cleveland C, Smith MH, Kari Connolly M, Katsumoto TR, et al. Brief Report: Whole-Exome Sequencing for Identification of Potential Causal Variants for Diffuse Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis & rheumatology. 2016;68(9):2257–62. doi: 10.1002/art.39721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnett FC, Gourh P, Shete S, Ahn CW, Honey RE, Agarwal SK, et al. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II alleles, haplotypes and epitopes which confer susceptibility or protection in systemic sclerosis: analyses in 1300 Caucasian, African-American and Hispanic cases and 1000 controls. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2010;69(5):822–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.111906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1980;23(5):581–90. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(11):1747–55. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan ND, Shah AA, Mayes MD, Domsic RT, Medsger TA, Jr, Steen VD, et al. Clinical and serological features of systemic sclerosis in a multicenter African American cohort: Analysis of the genome research in African American scleroderma patients clinical database. Medicine. 2017;96(51):e8980. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adeyemo A, Gerry N, Chen G, Herbert A, Doumatey A, Huang H, et al. A genome-wide association study of hypertension and blood pressure in African Americans. PLoS genetics. 2009;5(7):e1000564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome research. 2009;19(9):1655–64. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kochi Y, Suzuki A, Yamada R, Yamamoto K. Ethnogenetic heterogeneity of rheumatoid arthritis-implications for pathogenesis. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2010;6(5):290–5. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Isac E, Bossini-Castillo L, Palma AB, Assassi S, Mayes MD, Simeon CP, et al. Analysis of ATP8B4 F436L Missense Variant in a Large Systemic Sclerosis Cohort. Arthritis & rheumatology. 2017;69(6):1337–8. doi: 10.1002/art.40058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.