Abstract

Over the past two decades, two-dimensional infrared (2D IR) spectroscopy has evolved from the theoretical underpinnings of nonlinear spectroscopy as a means of investigating detailed molecular structure on an ultrafast timescale. The combined time and spectral resolution over which spectra can be collected on complex molecular systems has led to the precise structural resolution of dynamic species that have previously been impossible to directly observe through traditional methods. The adoption of 2D IR spectroscopy for the study of protein folding and peptide interactions has provided key details of how small changes in conformations can exert major influences on the activities of these complex molecular systems. Traditional 2D IR experiments are limited to molecules under equilibrium conditions, where small motions and fluctuations of these larger molecules often still lead to functionality. Utilizing techniques that allow the rapid initiation of chemical or structural changes in conjunction with 2D IR spectroscopy, i.e. transient 2D IR, a vast dynamic range becomes available to the spectroscopist uncovering structural content far from equilibrium. Furthermore, this allows the observation of reaction pathways of these macromolecules under quasi- and non-equilibrium conditions.

Graphical Abstract

I. Introduction

Traditionally, infrared spectroscopy has focused mainly on the identification of specific functional groups within a variety of molecular scaffolds. However, the advent of the twenty-first century has seen the reemergence of infrared spectroscopy as a tool of choice for analysis in nanotechnology, medicine, and biotechnology.1–3 Advances in materials science and theory have overcome several challenges to achieve the modern, structurally sensitive, time-dependent methods that have led to this resurgence in IR spectroscopy. New multidimensional nonlinear coherent spectroscopic techniques can resolve ambiguity in spectral features resulting from overlapping vibrational bands and convoluted line-broadening processes.4 Whereas one-dimensional methods project the molecular response of systems with many degrees of freedom onto a single frequency axis which makes detailed analysis difficult due to overlapping signals, multidimensional spectroscopies can disentangle the underlying molecular interactions using multiple light interactions. The molecular response, in the form of a vibrational echo, allows the system to be observed with significantly improved time and spatial resolution. Advances in optical technology progressively led to more precise time resolution allowing for even more spectral resolution.5 Although multidimensional methods, such as two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance (2D NMR) have been used for some time, infrared spectroscopy provides a means to apply similar approaches with faster time resolution to study molecules in anisotropic media,6,7 thus enabling a variety of applications in chemistry and biophysics.

Prior to the development of two-dimensional infrared (2D IR) methods, X-ray crystallography and NMR measurements provided atomically resolved structures of a wide variety of biomolecules. While these techniques resolved static structures to give important insights into biomolecular function, biomolecules undergo conformational changes and transient molecular interactions to perform various tasks and are therefore dynamic entities.8 Time-resolved X-ray crystallography remains technically challenging to apply on a broad scale,9,10 while 2D NMR captured many of these time-dependent structures, but is typically hampered by the limitations of NMR methods in that they can only follow such structural changes on millisecond timescales.11 2D IR spectroscopy can resolve equilibrium processes on picosecond or faster timescales through either dynamics of conformational distributions or mapping vibrational coupling between molecular groups to obtain relative positions and orientations.12,13

For example, the initial movements that occur as an unfolded peptide chain transforms into a helix or sheet occur on an extremely fast time-scale (under a nanosecond), yet are instrumental in determining how the motif behaves relative to the larger structure.14 The complexity of the factors involved allows for numerous variations upon basic motifs, with small yet significant structural changes occurring on a variety of timescales ranging from the ultrafast to the ultraslow.15 This variety of possible motions causes extreme difficulties for accurate modeling on an atomic level, as these small fast motions may by instrumental in determining the subsequent folding pathway. Knowledge of these motions associated with the folding pathway provide insights into the possible misfolds that can occur leading to disease. Oftentimes, it is these initial movements that are altered leading to macroscopic changes in proteins resulting in some malfunction of the system. Thus, the insights provided about the folding pathway can lead to therapeutic treatments. Furthermore, knowing how secondary structures are affected by their environment from both intramolecular and solvent effects would allow the generation of algorithms with greater predictive power. The development and application of transient 2D IR methods in this area allows for the assessment of structures with sufficient molecular detail in a time-dependent manner and provides an avenue to push the limits of molecular dynamics simulations.

Several challenges remain in understanding the behavior of proteins such as determining the relevant kinetic events and transition states in folding processes, as well as how proteins interact with membranes, hydrogen bonds, and dimer or higher-order oligomer formation. Transient two-dimensional infrared methods are well-suited to the study of quasi- or non-equilibrium states with high time resolution (< 150 fs) through the use of pulsed ultrafast lasers and significant amount of information obtainable via vibrational spectra.13 The efficacy of time-dependent 2D IR techniques depends on the ability to enact specific changes on target molecules at a short time scale. Fast mixing methods, such as stop-flow or continuous flow, cannot effectively function on the sub-microsecond scale, yet molecules can exhibit structural changes in sub-nanosecond or even faster timescales along those reaction pathways. To isolate the transient structures along reaction pathways of interest 2D IR must be combined with a rapid initiation technique.

Temperature jump (T-Jump) has been used to obtain significant information about biological molecules16,17 on the timescale of a few nanoseconds to microseconds. This relaxation technique provides a comprehensive means of initiating a folding process without altering the target molecule. Alternatively, if a specific starting configuration of the target molecule is desired and/or faster events are of interest, it is useful to exploit the ability of certain species to undergo rapid conformational changes via photoisomerization and photodissociation. By inserting various groups that can be triggered via an ultrafast light pulse into a larger biomolecule, phototriggers and photoswitches constrain the molecule to a well-defined initial condition to observe quasi- or non-equilibrium conformational changes on the order of 1–10 ps and beyond. These various time scales and photoinitiation methods are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Various effective time scales of techniques for observing conformational changes in biomolecules.

II. Equilibrium 2D IR Spectroscopy

The implementation of 2D IR spectroscopy was ushered in with the development of powerful pulsed lasers that allowed for the generation of reliable, affordable femtosecond IR.7 The intrinsic high time resolution of these pulses provide a means to freeze out slower motions and capture the sub-picosecond and picosecond dynamics. While the basic principles of 2D IR have been discussed at length elsewhere,13,18 briefly, a typical 2D IR setup involves the production of three phase-locked IR femtosecond pulses in a boxcar or pump-probe configuration sent at specified time intervals to acquire a 2D IR spectrum.19 The 2D IR echo signal is due to the third-order macroscopic polarization generated by the excitation of vibrational energy states allowing the full three dimensional response of the system to be measured at the picosecond or faster timescale.20 The combination of high resolution and ultrafast timescale is of critical importance in observing chemical and physical processes such as solvent-molecule dynamics,21,22 structural changes,23,24 chemical exchange,25,26 etc. If the system is restricted to excite a single vibrational mode, two peaks arise in the 2D IR spectrum yielding information about the 0 to 1 transition of the target vibrational mode and 1 to 2 transition of the same mode.19,27

Each excited oscillator will maintain a certain frequency distribution until several dephasing processes occur which leads to spectral diffusion. This spectral diffusion is captured by the frequency-frequency correlation function (FFCF). By introducing a waiting time, T, into the pulse sequence, the FFCF resulting from significant spectral diffusion can be recovered. Change in this correlation function can reveal the effect of solvent upon the signal of interest, for example hydrogen bond dynamics in the amide I mode of a peptide.28 As 2D IR diagonal signals separate out the inhomogeneous components from the homogeneous components present in the system, the time-dependent information provided by multidimensional spectroscopy is greatly enhanced from linear infrared.29 Spectral diffusion is affected by intermolecular and intramolecular surroundings along with their induced electric fields on the vibrational mode. By using transient two-dimensional infrared, the conformational distribution and dynamics behind this dephasing can be directly observed.

When more than one vibrational mode is excited, cross peaks result from the dipolar interactions between vibrational modes, interconversion between chemical species or environments, and intra- or intermolecular vibrational relaxation. These cross peaks are the ‘hallmark’ of two-dimensional spectra due to their distinct appearance, and contain information on relationships between their respective modes.19 Inaccessible to linear methods, the cross peaks in multidimensional spectra are powerful tools for the analysis of complex systems. 2D IR methods developed as analogues of those in NMR have greatly advanced the field of 2D IR spectroscopy by using these cross peaks.20,26 The precise time and structural resolution is limited by the vibrational lifetime of the probes being utilized, usually between 2–4 ps.30 As vibrational lifetimes are often short relative to the time window of interest, continuous monitoring of larger backbone conformational changes on the nanosecond to millisecond timescale is not feasible, motivating ongoing efforts to develop IR probes with longer lifetimes. Some promising results include probes using thiocyano-, selenocyano-, and isocyano-functionalized amino acids.31,32

III. Optically Initiated Transient 2D IR Spectroscopy

The goal of transient 2D IR is to widen the range of the applications of 2D IR into the quasi- and non-equilibrium regime, to bring to fruition ultrafast snap shots of protein motion and chemical reactions on free energy surfaces on much longer timescales than are allowed for by lifetime limited measurements. In these non-equilibrium experiments, the triggering of a structural change by a UV/visible pulse is followed by a pulse sequence for a typical 2D IR experiment. By measuring a full heterodyned/homodyned 2D IR signal following a given delay from the triggering pulse, it is possible to observe vibrational coupling and spectral diffusion at any point along the reaction pathway, limited only by the precision of our control of the structural change induced by the trigger.

A transient 2D IR (t-2D IR) experiment involves the use of a short, actinic pulse prior to collecting the 2D IR spectrum, in order to track the response of the system. By varying the time delay between the initiating pulse and the infrared probing sequence, t-2D IR experiments can be performed from initiation to a point where the system approaches its equilibrium state. The t-2D IR spectrum is often reported as a difference 2D IR spectra between initial and the transient species. Negative peaks are due to depleted initial population and positive signals result from the newly formed transient photoproduct.33,34

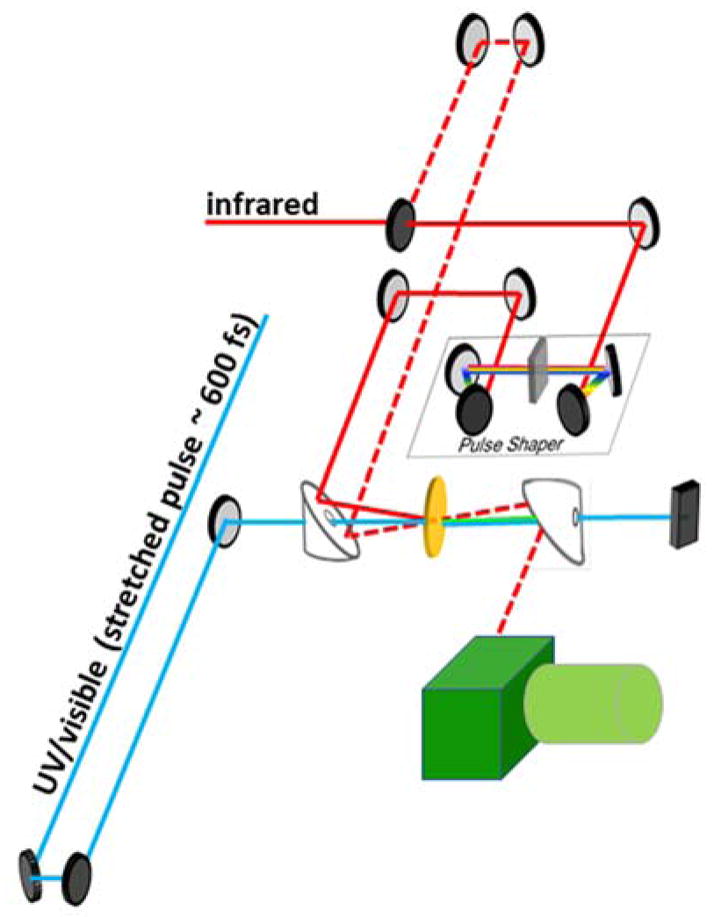

Figure 2 depicts a sample t-2D IR setup with pulses originating from an OPA providing 4–7 μm mid IR pulses and a temporally-stretched and tunable excitation/triggering pulse. The infrared pulse is split into two arms for the pump and probe IR beams for the 2D IR measurement in the pump-probe geometry. The first arm generates an IR probe beam which often has a time delay range of 120 ps. The second arm is diverted into an acoustic optic modulating pulse shaper to generate two pump pulses separated by specific time delays. These resulting echo signals of the 2D IR measurement allow the structural determination of the peptides during transient states. The pulse shaping speeds up data acquisition and facilitates control of phase, pulse sequences, and shapes to optimize the experiment. By determination of coupling through these transient 2D IR measurements, changes of angles and bond distances within a structure during the time evolution are uncovered.28

Figure 2.

Typical transient 2D IR optical design with pulse shaping module.

The complexities involved in protein folding give rise to numerous short-lived intermediate states along various relaxation pathways, providing a need for the rapid probing of transient structures. In order to access these states, the protein system needs to be initiated far from equilibrium by some external perturbation to watch the structural relaxation as it approaches the equilibrium state. The overall goal is the direct observation of the earliest steps of protein folding which may lead to observing the dynamics of disordered and misfolded states that often result in disease. The initial pulse in transient 2D IR results in a fifth order spectroscopy with potentially multiple complex transitions. It has been demonstrated in 2D IR that it is possible to manipulate band intensities by employing different polarizations to selectively enhance or diminish different features in the spectrum.35 As cross peaks and diagonal peaks can exhibit strong polarization dependence, by taking appropriate linear combinations of signals, the enhancement or complete suppression of selected peaks is possible.36

In these experiments, the possibility of signal drift and instability due to laser fluctuations and the energy of the pulse heating the sample creates additional complications for signal gathering. The number of factors that must be taken into account when selecting the optical triggering pulse increases with the complexity of the setup and number of pulses used. Signal drift can be accounted for by using the IR beam as a reference. Increasing the beam size and stretching the pump pulse width has been employed through the use of glass prisms, which also reduces the beam power. 37

A. Photoswitches and Phototriggers

Some of the pioneering ultrafast transient IR experiments were performed by Hochstrasser et al. using UV light pulses to induce the photodissociation of carbon monoxide from complexes of hemin and myoglobin.38,39 Some of the early extensions of this work to 2D IR were performed by Kubarych et al. on Mn2(CO)10 with multiple substituents, followed by studies of Bredenbeck et al. on Re(CO)3Cl complexes.40,41 These results demonstrated conclusively that for t-2DIR could reveal previously inaccessible information about the FFCF for metal-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) and solvent coupling for excited states of inorganic species. Unlike metal carbonyl complexes, most peptides do not feature a well-defined functional group which localizes the electronic excitation state (with exceptions such as rhodopsin and various chlorophylls). Although the addition of a triggering functional group undermines the intrinsic non-perturbative nature of infrared spectroscopy, the use of a phototrigger is necessary for inducing a fast, controllable conformational changes in these complex peptides/proteins. To be of practical use, the phototrigger must have high photochemical quantum yields at frequencies that are non-damaging towards sensitive biological structures such as the absorptions of the peptide backbone, be biocompatible, and have an ultrafast reaction rate. If dissociation is utilized, it is best to avoid homolytic photoproducts so that the structure has negligible opportunities to undergo geminate recombination, interface chemically with the peptide backbone, and/or undergo other side reactions. On a similar note, the heat generated by the phototriggering process dissipates through the larger structure within few picoseconds and becomes negligible. This does not result in significant changes in the structural rearrangement downstream from the photolinker due to the bulk movement of the molecule being relatively slow compared to the redistribution of the heat energy. If observations on such brief time scales are necessary, these thermal effects must be accounted for in the analysis. The energy of UV-Visible trigering pulses are too small to cause significant bulk heating of the sample. Figure 3 depicts a peptide that is constrained by a photolyzable covalent linkage, i.e. a photolinker. The peptide begins in an energetically unfavorable conformation held fast by the yellow linker in an initial condition near but not at equilibrium. Upon initiation of the conformational change by a triggering pulse, the bonds in the photolinker dissociate and the peptide is released. The fast structural movements are observed via 2D IR spectroscopy as the peptide recovers to its equilibrium energy conformation. As mentioned above, these changes are often small relative to the initial signals, and a difference spectrum is often used to help amplify the overall spectral change. In this way, the 2D IR approach, combined with phototriggering, can address questions of conformational dynamics and structural change of backbone motions directly. Furthermore, the initial condition can be defined by synthesis, and then in conjunction with short pulse photolysis, evolution of the resulting structure distribution can be measured at different snapshots along a pathway. One of the difficulties is to find effective triggers to sequester non-equilibrium geometries of small and medium size peptides. No single functional group can fulfill the above-mentioned properties of an ideal photolinker. Thus, the incorporation of the desired phototrigger should take into consideration the relevant photophysical and photochemical properties of the system in question. Specific concerns regarding each functional group will be highlighted in the relevant sections.

Figure 3.

(top) A photolyzable linker constrains a peptide in an energetically unfavorable configuration until released via photodissociation, after which the peptide relaxes to an equilibrium position. (bottom) Simulated 2D IR spectra before and after release of the photolinker. A 2D IR difference spectrum is also shown.

1. Disulfide Linkers

One early attempt at satisfying the criteria for an optimal photo-initiator involved the usage of disulfide linkages intrinsic to some protein systems. The S-S bond is homolytically broken using ~266 nm light liberating thiol radicals on a timescale of < 200 fs. Due to the comparatively slow resulting motion of the attached peptide, the geminate recombination of the radicals readily occurs due to the radicals’ close spatial proximity. Although the quantum yield for this photoreaction is approximately 0.10 ± 0.04, this photolysis yield is hindered due to the rapid recombination in solution, significantly limiting the population of protein molecules undergoing a conformational transition.42,43 Furthermore, the formation of the radicals can lead to reactivity with certain side chains and even the peptide backbone, obscuring the information associated with the folding process.

A variant on the disulfide bridges using an aryl disulfide chromophore developed by Hochstrasser et al. proved effective at increasing the lifetime of the radicals via an alternative excited state, allowing a greater range of timeframes up to 2 ns to be studied using this reaction.44 Other attempts to resolve the radical recombination issue proved to be less successful. Adding additional side groups for steric hindrance not only made the linker less versatile, but also proved ineffective at preventing recombination. Attempts to create a higher degree of strain on the peptide backbone to force the radical groups apart can possibly limit the folding processes that can be studied, but again fails to solve the problem, as the movement of the peptide still takes place an order of magnitude too slow to be relevant toward the recombination rate.44. Experimental studies showed that the incorporation of radical-stabilizing amino groups to create two thiotyrosine derivatives, denoted as Tty and Aty, created two potential linkers with double the lifetime of the radical species, allowing radical recombination to act as a means of not only inducing a conformational change, but to serve as a probe for measuring the rate as well.44 Thus, it seems that the only success to improve the disulfide linker involves changing the nature of the excited state or the reactivity of the photoproducts.

Further inspiration came from studies of oxytocin and vasopressin, two biomolecules that contain a native disulfide linker. Based upon their structure, Kolano et al. synthesized two cyclic disulfide-bridged peptides via posttranslational modification of cysteine residues. These small peptides are useful model systems to study some of the fast initial steps in peptide folding via photolysis of the disulfide linker.45 The cyclic peptide cyclo(Boc–Cys– Pro–Aib–Cys–OMe) was selected for transient infrared studies as it is a rigid structure that is forced into a β-turn by an intermolecular hydrogen bond between the two cysteine residues, and furthermore it exhibits strong signals due to conformational homogeneity. Upon photolysis of the disulfide linker, the β-turn conformation is released allowing the molecule to adopt a more random and disordered structure that is more energetically favorable. This specific photolytic linker limits the conformers to a small subset of the possible configurations accessible within the equilibrium distribution, thus allowing individual interactions of interest to be studied. Hamm et al. extended these studies to transient 2D IR spectroscopy by cross-linking two cysteines close in the peptide sequence with a disulfide linker to constrain the peptide at the amino acids Cys and Aib stabilized by an intramolecular hydrogen bond (Figure 4).43,44 The use of disulfide linkages resulted in the potential creation of undesirable photoproducts due to side reactions. In order to overcome this potential setback, two sets of 2D IR spectra were recorded simultaneously; one with and one without an ultraviolet pulse. Then, the transient 2D IR difference spectrum was obtained by subtracting these two spectra. It should be noted that the aforementioned issues of geminate recombination, although somewhat reduced due to peptide backbone strain, were still present. However, by using the transient difference spectrum, only signals coming from backbone changes were detected. Distinct signals for the amide I modes of the various residues were clearly observable with the use of difference spectra even without isotopic labeling.

Figure 4.

A disulfide linker constrains the peptide until photodissociation via a 270 nm pulse, resulting in peptide relaxation back to an equilibrium conformation. Adapted with permission from Refs. 43 and 46. Copyright 1997 and 2007 American Chemical Society.

Transient 2D IR spectra performed by Kolano and Hamm et al.8 on theses peptide with delay times of 3 ps, 25 ps and 100 ps from the UV pulse indicated the evolution of a transient cross peak resulting from structural changes in the backbone (Figure 5). This cross peak was identified as vibrational coupling between the carbonyl groups of the Aib and Cys across from each other in the cyclic chain. The intensity of the cross peak increases with delay time relative to the corresponding diagonal signal. Molecular dynamics simulations indicate that the backbone structure at the Boc-Cys-Pro fragment does not change after release of the disulfide constraint resulting in the conformational transition. Thus, it is expected that no net signal was observed in two-dimensional difference spectra for these residues. However, changes in both orientation and distance of the C=O groups found between the cross strand Cys and Aib residues are suggested to result in a modified C=O coupling due to the formation of a hydrogen bond. The coupling constant between isotopically labeled amide I modes in the structure was used to determine the strength of the hydrogen bond between the residues. Interpretation of the transient species via non-equilibrium molecular dynamics showed that the distribution of hydrogen bond distances widens, but the conformational change does not cause the hydrogen bond to break entirely. Observation of the final structure following 500 ps indicates that the hydrogen bond exists in a two-state equilibrium between an open and closed peptide conformation separated by a small energy barrier, consistent with IR studies performed on the photolyzed structure.45,46

Figure 5.

a) Transient linear IR and b) Two-Dimensional infrared spectra of a β-turn peptide. c) horizontal slices of the 2D spectrum as indicated by the lines in part b. Reprinted with permission by Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature. Ref. 8, copyright 2006.

2. Tetrazine as a Phototrigger

Disulfide linkers are not the only attempt at constraining a molecule to a small non-equilibrium distribution. Azines are a family of nitrogen containing compounds isoelectronic to benzene. Upon electronic excitation, they do not typically fluoresce, but instead undergo photochemical decomposition with a photoproduct yield near unity. Figure 6 depicts the dissociation of S-tetrazine, a member of the azine family, upon irradiation with visible light (λ = 532 nm) yielding the relatively unreactive photoproducts, HCN and N2, making it a promising candidate for a phototrigger 47 The general use of the unmodified tetrazine is inhibited by somewhat by thermal decomposition around room temperature (300 K), and significantly inhibited by the rapid the quenching of the hot vibrational state by the attached biomolecule.48 The mild thermal stability issue can be overcome by simple substitution, as dimethyl-S-tetrazine and diphenyl-S-tetrazine show thermal stability at temperatures greater than 341 K. The internal conversion of the hot vibrational mode to the ground state remains more challenging, as the number of substituents attached to the tetrazine ring serve to increase the number of modes accessible for internal conversion, thereby reducing the longevity of the hot vibrational state. This process diminishes the photoproduct yield to as little as 2%. A desirable substituent group must balance feasibility of incorporation into a peptide system with the ability to undergo photolysis rather than non-radiative transition to the ground state.

Figure 6.

Photodecomposition of s-tetrazine into nitrogen and hydrogen cyanide.

As the photodissociation pathways of tetrazines became understood, a rational development of improved tetrazine linkers to address this issue was possible. Since the mechanism of dissociation of S-tetrazine is through a hot vibrational state,47,49 it was believed that adding a heavy atom to the parent tetrazine prior to the substituent might trap the thermal energy required for photodistribution in the ring. Based on this theory, Smith and coworkers developed disulfenyl tetrazines with the intention of extending the lifetime of the excited vibrational state. With the addition of an n→π* transition at 410 nm due to the attached sulfur atoms, the photoproduct yield increased to an acceptable 22% regardless of the substituents attached to the sulfur group.48 This sulfur also provided the perfect scaffold to attach a peptide system, through the use of cysteine residues. A new photolysis pathway was later uncovered for this scaffold that did not depend on the hot vibrational state like the parent compound, but instead the photodissociation occurred via a direct pathway from a higher excited state. Observations that the excitation dependence of the photoproduct yield and photodissociation rate occurred faster than the excited state lifetime provided evidence leading to the explanation for this alternate pathway.48

One of the first biological applications utilized oxytocin as a model system, similar to prior experiments that took advantage of disulfide linkage. In this case, the disulfide linkage was replaced with a tetrazine linker. Upon irradiation, the formation of the SCN photoproducts were detected on the timescale of much simpler test molecules showing that the photodissociation pathway was unaffected by the presence of the biological system. Tucker et al. investigated the non-equilibrium states associated with α-helical folding using S,S-tetrazine as a phototrigger in an alanine-rich peptide.14 This S,S-tetrazine linker was incorporated into the peptide at Cys10 and Cys12 to distort a single helical turn within an alanine based helical peptide (Figure 7). 13C=18O isotopically edited amino acids were placed at key positions within the peptide to monitor changes in helical content via vibrational coupling between these amide I isotopic labels observed in the transient 2D IR spectrum. The 2D IR spectra taken at different time delays from release of the tetrazine constraint were used to develop a molecular movie of the reformation of the helix on the downhill side of the energy barrier, shedding some light on the propagation process. The experimental data agreed with estimates of the rates determined for helix propagation in kinetic zipper models suggested by theory.50,51

Figure 7.

Helical reorganization after photorelease of tetrazine linker indicates rotation of the backbone around the psi dihedral angle. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 14. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

The Hamiltonian of the excitonic states was constructed to obtain detailed structural information from the two-dimensional spectra. The vibrational exciton states (ν = 0 → 1 transitions) here are due to interactions between the localized amide I modes of neighboring amino acids. An observed shift in the peak position and changes in width result from some combination of the exciton splitting and the relative intensities of the exciton transitions. Thus, structural information requires the computation of the site energies, electrostatic potential, nearest-neighbor φ/ψ coupling, and long range dipole–dipole interaction as accurately as possible.19 Figure 8 maps the changes in peak position and spectral width of the 2D IR diagonal traces to an exciton resonance pair model. The change in the experimentally observed peak widths is due to a change in dipole-dipole coupling, which is interpreted as a rotation around the psi angle of the peptide. NMR analyses of tripeptide systems gives evidence that this is due to backbone distortion from the helical structure of the constrained region, which is reproduced by the non-equilibrium MD simulations.52

Figure 8.

Normalized diagonal traces of 2D IR spectra modeled as a two exciton system. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 14. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

3. Azobenzene and Photoswitchable Folding Dynamics

Although phototriggers have been shown to be quite useful in transient 2D IR studies, an alternative is to induce a conformational change through photoswitches. Photoswitches undergo isomerization leading to peptide structural motions as a results of configuration changes of the switching molecule, whereas phototriggers contain bonds which break upon exposure to a particular wavelength.

Azobenzene, a chromophore with two isomers that were first isolated in 1937,53 undergoes an extraordinarily rapid rate of photoisomerization (~200 – 300 fs) from cis- to trans- or the reverse, depending on the frequency absorbed (Figure 9a).54 The advantages of azobenzenes are numerous: they exhibit the largest range of activation wavelengths for currently known photoswitches (300–630 nm), they have good photoactivated state stability, and the isomerization due to rotation of the rigid rings around the central double bond gives predictable changes in distance.. Moreover, they are easy to synthesize and can be linked to proteins by selective reactions with the thiol side chains of cysteine residues.55 The UV-Visible absorption spectrum of the trans-isomer consists of two distinct bands: the strong UV band (320 nm) due to the symmetry allowed π → π* transition (S0 →S2), and a weaker band (450 nm) due to the symmetry forbidden n → π* transition (S0 →S1), while the cis isomer has a somewhat reduced π → π* transition (270 nm, 250 nm) and a stronger n → π* transition (450 nm). For cis-to-trans isomerization, the disappearance of the cis peak (430 nm) occurs after 170 fs and is followed by the formation of the trans-absorption band (around 360 nm). The trans- to cis- the isomerization is somewhat slower, t = 320 fs. After the ultrafast 170 fs cis-to-trans isomerization, internal vibrational redistribution proceeds before 1 ps elapses and finally, over about 10–20 ps, the vibrationally hot product transfers energy to the surroundings. Even taking into account this 20 ps vibrational cooling time, this process is still faster than T-Jump, which can only achieve > 100 ps resolution.56

Figure 9.

(left) Azobenzene undergoes isomerization from trans to cis causing the α-helix to become unfolded. Upon irradiating with 450 nm, the cis-azobenzene reverses to the trans isomer, allowing the helix to refold. (right) 2D IR spectra taken of various isotopic labels within the helix before and after photoisomerization. Adapted with permission from Ref 59. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

Transient 2D IR spectroscopy has taken advantage of azobenzene to access nonequilibrium states with extremely high time resolution, allowing exploration of intermediate states and kinetic traps in biomolecules. Considerations involving the suitability of a photoswitch and its placement within the system must take into account the relevant structural and spectral properties. Upon triggering, the photoswitch must generate a desired structural change without hamper the folding energy landscape. Some constraints on the molecule during protein folding or binding can alter the energetics and even change the folding pathways entirely. The cis- to trans-isomerization also limits the overall relaxation distance by the length of linker, and the phenyl rings may be a source of steric hindrance, affecting nearby structure. Depending on the environment, these aromatic rings can also occupy the spectral window commonly used in peptide studies at 1520 – 1590 cm−1, overlapping the isotopically labeled amide I region. If this region is to be used, isotopically substituted 13C-D azobenzene compounds result in a clean spectral window between 1550–1600 cm−1.57,58

Bredenbeck performed the initial transient 2D IR experiment involving azobenzene on an octapeptide system.28 Using an azobenzene photoswitch as a means of frustrating the relaxation of an octopeptide, transient linear and 2D IR difference spectra were obtained by illuminating the molecule at 363 nm to obtain the unfavorable conformation (cis-). Upon exposure to 420 nm light, the azobenzene adopted a trans-state allowing the peptide to relax to a more favorable configuration. Vibrational cooling occurred after 20 ps, allowing signals to be obtained immediately following the conformational change. Bredenbeck observed that although the photoproduct showed little time dependence for linear methods, transient 2D IR spectra showed strong changes in homogenous broadening, indicative of a complex potential energy space for what appeared to be a simple two-state process. This indicates that multidimensional methods may to see beyond the simplified linear picture to expose complex, time-dependent processes.

Hamm and coworkers performed a combined 2D IR and transient IR study involving the insertion of an azobenzene derivative into the helix such that the α-helical peptides was stabilized with the linker in the trans-isomer.59,60 Again, the azobenzene was illuminated to place it in the -cis conformation, then switched to –trans to initiate the folding process. The four different isotopomers investigated using infrared spectroscopy were: L4, L7, L9, and L11, with the number indicating which amide I′ mode was isotopically labelled (Figure 9b). CD spectroscopy confirmed that helicity of the peptide was reduced from roughly 70 % to 20 % upon trans- to cis-azobenzene isomerization at 4°C. Transient IR showed early signals up to 30 ps are dominated by the vibrational relaxation of the linker, demonstrating that although the rotation may proceed at a sub-picosecond time scale, the resolution overall linker is not always suitable predictable due to behavior of the bulk system.

The Two-dimensional spectra were used to corroborate the transient linear IR spectra, and the resulting data was interpreted based on molecular structures obtained by MD simulations. The resulting changes of the amide I′ mode showed a shift to a lower frequency in the folded conformation, from 1680/1655 to 1630 cm−1. The crosslinker considerably increases the helix propensity in its trans-state, and was confirmed by CD measurements. Although no transient 2D IR work was done, the successful use of transient IR methods with azobenzene in combination with the additional information provided by the lineshapes from multidimensional methods suggests that photoswitch initiated transient 2D IR shows promise as a method for resolving short lived states in helix folding.

Following up on this, Hamm and coworkers also observed how folding times differ in a peptide when the temperature is changed.61 They monitored this folding for temperatures ranging from 6°C to 45°C and found that the different sites fold in a noncooperative manner, with of the sites exhibiting a decrease in hydrogen bonding character upon peptide folding. This suggests that the unfolded state of the peptide is not entirely unstructured and that nucleation occurs at multiple sites along the helix, supporting the multiple nucleation site model. Although no practical implementation has been found thus far, it should be noted that other potential photoswitches include compounds such as stilbenes, diarylethenes and acylhydrazones, and rhodopsin-like molecules.62

B. Temperature Jump

A Temperature Jump (T-Jump) is an instantaneous rise in temperature resulting in a shift in the chemical equilibria, followed by a relaxation period during which the system cools back to the original temperature to regain the initial chemical equilibrium. The structural changes occurring during this relaxation method can be followed by many types of spectroscopy. Well before the development of ultrafast pulsed laser systems, T-jump infrared spectroscopy was known to be a versatile method for obtaining information about the kinetics of folding/unfolding of peptide and protein systems. As ultrafast linear and nonlinear spectroscopy advanced, the limitations of this method focused on the ability to quickly induce a temperature change in solution. Originally done via electrical discharge, modern T-Jump experiments on biological systems are most often performed by exciting an overtone band of water allowing for precise timing and rapid heating.63 As deuterated water is often preferred for biological systems, the overtone of the OD stretch is excited by wavelengths ranging from 1900–2200 nm. The heating of water using a pump pulse can be achieved by Stokes shifted stimulated emission of a commercially available laser such as an Nd:YAG.64 Hydrogen and methane gas under high pressure can be used to Raman shift the Nd:YAG pulse to 1907 nm and 1542 nm, respectively.65,66 Since the variety of timescales and conformations found in peptides is vast, temperature jump remains a powerful technique due to the versatility of its application.67

T-jump spectroscopy measures the relaxation of an equilibrium population of conformations via transient difference spectra of the amide I mode. The 2D IR temperature jump is performed by collecting 2D IR spectra at different delays as the population of molecules relaxes back to the equilibrium distribution prior to the T-jump. These transient 2D IR spectra are often subtracted from an equilibrium 2D IR spectrum resulting in a transient difference spectrum. Difference spectra have two main types of peaks: gain peaks and loss peaks (Figure 10a). Gain peaks are characterized by the same red/blue orientation as the equilibrium spectrum while the loss peaks are the opposite.30,68

Figure 10.

T-Jump transient 2D IR spectra of insulin a) sample chart of spectral changes in t-2D IR. Difference spectra of insulin at b) Tf = 45 °C and c) Tf = 50 °C following a time jump with different polarization and concentrations. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 68. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

One major advantage of T-jump is that the application does not require site-specific alteration of the molecule in question. This allows for versatility and ease of use, at the cost of precision control of the heating process.67 T-jump studies are a quasi-equilibrium transient experiment measuring the change between a population of various transient species as it relaxes to equilibrium. Heating the water directly with short pulses is ultrafast, and studies on water have reported a thermalization time of as short as 5 ps.69 For larger molecules, the duration of a T-jump experiment is limited by the rate of heat transfer from the solvent to the molecule via thermal diffusion, resulting in a usable experiment lifetime estimated to be from hundreds of picoseconds to hundreds of microseconds.70,71 Furthermore, thermal lensing can occur and produce artifacts in spectra due to a rapid heating of a medium that gives rise to a locally inhomogeneous refractive-index profile.72 As 2DIR experiments detect small changes between the starting and final configuration, this small change due to heating of solvent can result in significant background noise, and must be subtracted out to obtain the change to the target system. Thus, it restricts the intensity of the probe beam to 20% of the pump beam.73 Homogeneous broadening due to rising temperature also leads to a difference in the peak shape and must be considered in the analysis.

A more unpredictable effect of uneven heating is the sudden formation of bubbles in a liquid medium, also known as cavitation. When the tensile pressure is in excess of the tensile strength of the medium, pockets vacated by the solvent give rise to bubbles, resulting in unwanted artifacts in temperature-jump experiments. Uneven heating may also result in the propagation of photoacoustic waves through the medium, causing distortions in the solvent pressure. As this occurs on a slower time scale (1 μs) it does not propagate fast enough to be a substantial source of noise for ultrafast processes.

Some of the first transient 2D IR T-jump experiments focused on the folding kinetics of HP35, mutant of monomeric l repressor, ubiquitin, and the WW domains.63 Investigating two well studied proteins, HP35 (Chicken Villin) and ubiquitin, provides a way to observe changes from T-jump transient 2D IR studies upon simple common protein motifs in an easily controlled structure. HP35 is a short peptide with three α-helices, and ubiquitin contains four β-sheets and one α-helix. Tokmakoff et al. was able to determine the kinetics and the specific structural changes occurring in the backbone conformation of ubiquitin during protein unfolding.74 It was found that there are two distinct stages of protein unfolding of ubiquitin: a 100 ns – 0.5 ms kinetic component in which the two β-sheet transitions are lost, and a 3 ms component where the protein undergoes relaxation with the energy following a stretched exponential fit. For HP35 a statistical mechanical model compares favorably with recent molecular dynamics simulations of HP35 folding.

The complex folding free energy landscapes of peptides demonstrate wide variation in behavior and hence dependence upon of fast kinetic phases. Temperature jump has been used to explore the significance of trap states in protein folding that cause deviation from the ideal of landscape theory- the concept that the native state of protein folding is necessarily the lowest energy state. A useful means of understanding protein folding is through Markov state models, which use path-based statistical mechanics to represent a given trajectory as a time series of system configurations over some interval. Transitions are determined by a transition probability matrix and occur at a fixed time interval. Studies involving Markov dynamics for β hairpin sequences indicate that dynamics fluctuate between active vs glassy behavior for TrpZip2 and numerous mutants.75,76

Another study using the transient 2D IR technique in conjunction with T-jump was conducted on the equilibrium relaxation of the interconversion between insulin dimers and monomers in solution.68 The two main features observed in the transient difference spectra of the insulin dimers were a decrease in the cross peak signal at 1642 cm−1 of the 320 μs spectrum (Figure 10b, green arrows) and an increase in the signal at 1660 cm−1 in the 560 μs spectrum (Figure 10c, purple arrow). The loss in the coupling peaks corresponds to the dissociation or disordering of the β-sheet features of the peptide while the gain feature in the 560 μs spectrum has been assigned to the presence of the monomer state. This confirms that the temperature jump induces the melting of two insulin dimers into a disordered configuration necessary for dissociation.

IV. Challenges of Transient 2D IR

When designing a time-dependent infrared experiment, the specific changes to be observed must be triggered on relevant timescales of interest. Once incorporated into peptide systems, a photolinker can hold the peptide in an energetically unfavorable starting conformation or a photoswitch can induce a constraint where desired. The conformational change or bond dissociation is triggered and the specific time desired by a light pulse. One important challenge is the time-consuming process of linking synthetic target peptides without causing distortions to the energy landscape of the native peptide. The target peptide’s potential energy surface may be sterically hindered or otherwise changed unintentionally, causing the peptide to be unable to relax to its native conformation or result in a different or more accessible energy minimum. This is not the case in the T-jump method, which trades specific site and time dependence for simplicity and a broad range of applicability. It is quite suitable for large-scale system dynamics, or when the desired properties are minimal sample preparation.

Transient absorption of the laser T-Jump pulse can lead to distortions of the signal due to the sample’s inherent linear response. Other challenges in the accurate implementation of T-Jump methods involves accurate synchronization in the time and phase domains due to the high energy low repetition rate lasers required for triggering. Bulk heating of the sample between laser shots for optically triggered experiments is another significant issue and it requires the use of rotating sample cells or a flow cell. Flow cells can cause turbulence in the solution and require higher sample volume, while rotating cells oftentimes create additional noise due to scattering.

One other concern is that as transient multidimensional laser triggered experiments are technically 5th order nonlinear experiments, they require a high signal-to-noise ratio as the difference signal has an intensity that is often a fraction of the equilibrium band. The noise from systematic sources of the laser setup and the environment causes homogenous broadening that overlaps the signal and will cancel out in the difference spectra.77 Furthermore, signal strength cannot simply be enhanced by increasing the power of the incident and probing beams due to the relative fragility of biomolecules. By alternatingly chopping one of probe beams, a baseline measurement can be made for each pulse. This signal is further processed by subtracting the difference spectra from the system when it is fully relaxed; creating a double difference spectrum that removes as much noise as possible from the relatively weak transient signal.

One last consideration in transient 2D IR methods is the choice of vibrational probes used. The utility of the amide I mode is limited by significant spectral overlap of residues, and their ability to only report on changes within the backbone. Although isotopic labeling of amides has been effective in many cases,78 the backbone is often limited in the structural information it provides about the larger surrounding environment. Furthermore, the shifted resonances can still overlap with resonances of amino acid side chains.79 One alternative for isotopic labelling of amides is the use of modified amino acid probes. One of the most commonly exploited to study biological processes is p-cyanophenyalanine (PheCN).80 Dynamics of the folded and unfolded villin headpiece (HP35) were measured with two CN-functionalized phenylalanine derivatives inserted into the hydrophobic core of the Chicken Villin peptide to measure solvent interactions compared to those of the chemically induced unfolded peptide.81 Although the stretching nitrile vibration has an extinction coefficient (~200 cm−1M−1) that is slightly smaller compared to amides, the transition lies in an isolated portion of the infrared spectrum (2,100–2,400 cm−1) making it easily detectable.82 Nitrile-based probes such as PheCN also have a longer lifetime than amides, ~4–5 times longer. A search for an improved PheCN has produced thiocyanate (SCN) and selenocyanate (SeCN) labeled side chains. These probes have increased the observation window with vibrational lifetimes exceeding ~300 ps.83 However, the tradeoff for these nitrile-based probes is the presence of a long lifetime for a decrease in the transition dipole strength. The asymmetric stretch of the azido group (R–N3) has a larger extinction coefficient than nitrile, trading a lesser dependence on the environment due to a smaller Stark shift for the advance of lower sample concentrations required.84,85 The 2D IR signal is still capable of detecting the spectral diffusion processes occurring due to the surroundings despite their short lifetimes (~1 ps). Since T-2D IR is a fifth order method, the quality of the signal obtained is highly dependent upon the vibrational lifetime. Thus, the choice of probe to be used is therefore highly dependent upon the system and properties of interest.

V. Closing Remarks

Due to innovations in laser technology in the last two decades, the tremendous versatility and resolving power modern pulsed lasers has given rise to a variety of powerful time-sensitive techniques for understanding molecular kinetics and structure. Transient 2D IR spectroscopy has provided a route for characterization of dynamic processes within a variety of biological pathways; such as transition states, peptide folding dynamics and dimerization, etc.28 By introducing constraints to narrow the structure distribution or increase the energy, the conformation evolution along non-equilibrium pathways can be traced as it approaches equilibrium by two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy, elucidating structural intermediates along the reaction pathway. By doing so, relationships can be established such as between two parts of a helix, solvent dynamics within an active site, or binding between two peptides.

Transient 2D IR methods allow spectroscopists to address questions that reach beyond traditional structural characterization to obtain both structures and distribution of ensembles along reactive trajectories based on initial conditions only rarely achieved in an equilibrium distribution. With a bias toward a particular starting configuration, usually close to the transition state, a structurally resolved transition path can be realized even beyond the largest energy barriers. Two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy was utilized to observe the dynamics within the M2 influenza membrane protein held in a lipid bilayer. Lineshape analysis of the spectra was essential towards determining the position of key residues involved in channel transport. Transient methods have the ability provide site-specific dynamic information as target molecules move through the channel and/or block the channel.86,87 These types of experiments will not only permit definition of early conformational reorganization but will also challenge state-of-the-art molecular dynamics simulations that relate to key metastable states, non-native contacts, and the rugged energy landscape far from equilibrium. However, the overall complexity of these experiments indicates that further development of nonequilibrium spectroscopy is still sorely needed as the field continues to advance.

The broad objective of these methods is to obtain a chemical bond scale description of the interactions that lead to productive conformational changes by examining the dynamic processes initiating by some technique. The search for generic molecular mechanisms for structure changes leading to desired states to help understand how particular structures form. Understanding and modeling molecular mechanisms for structural change allows for the development of means to induce desired folding states and prevent misfolded ones. For example, knowing the pathways that result in degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or cancer through misformed p53 proteins can lead to potential pathways for therapeutic intervention.

Transient 2D IR extends this to the observation of temporal information that is, at present, completely inaccessible to any other method. Theoretical two-dimensional infrared simulations will come into their own alongside other predictive models for spectroscopic methods, allowing rapid and accurate interpretation of data. This review hopefully illustrates the power of multidimensional infrared methods that lies in their inherent versatility and high time sensitivity.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was made possible by an NIH (R15GM1224597) grant to MJT.

Biographies

David G. Hogle received a B.S. in chemistry from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2004 and is currently enrolled in the doctorate program at University of Nevada-Reno. His work focuses on theoretical modeling of two dimensional infrared spectra and applications toward analysis of micropeptides.

Amy Cunningham received her undergraduate degree in chemistry from Linfield College in McMinnville, OR studying Raman spectroscopy. She received her Masters at the University of Nevada, Reno studying two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy of biomolecules.

Matthew J. Tucker received his B.S. in chemistry and B.A. philosophy from the University of Scranton, a small Jesuit university in Scranton, PA. During that time, his research focused on the biosynthetic labelling of proteins for NMR studies. He then moved to University of Pennsylvania for his Ph.D. in Biophysical Chemistry under Dr. Feng Gai working on the development of probes for both infrared and fluorescence spectroscopy. After receiving his PhD in 2006, he remained at the University of Pennsylvania for his post-doc under the advisement of Robin M. Hochstrasser working on 2D IR and transient 2D IR studies of biological systems. He is currently an assistant professor at the University of Nevada, Reno continuing his work on 2D IR probe pairs and novel transient 2D IR techniques.

References

- 1.Donaldson PM, Hamm P. Gold Nanoparticle Capping Layers: Structure, Dynamics, and Surface Enhancement Measured Using 2D-IR Spectroscopy. Angew Chemie-International Ed. 2013;52(2):634–638. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Middleton CT, Marek P, Cao P, Chiu CC, Singh S, Woys AM, de Pablo JJ, Raleigh DP, Zanni MT. Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy Reveals the Complex Behaviour of an Amyloid Fibril Inhibitor. Nat Chem. 2012;4(5):355–360. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramakers LA, Hithell G, May JJ, Greetham GM, Donaldson PM, Towrie M, Parker AW, Burley GA, Hunt NT. 2D-IR Spectroscopy Shows That Optimized DNA Minor Groove Binding of Hoechst33258 Follows an Induced Fit Model. J Phys Chem B. 2017;121(6):1295–1303. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalil M, Demirdoven N, Tokmakoff A. Coherent 2D IR Spectroscopy: Molecular Structure and Dynamics in Solution. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107(27):5258–5279. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid GD, Wynne K. Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. Ultrafast Laser Technology and Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aue WP, Bartholdi E, Ernst RR. 2-Dimensional Spectroscopy - Application to Nuclear Magnetic-Resonance. J Chem Phys. 1976;64(5):2229–2246. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamm P, Lim MH, Hochstrasser RM. Structure of the Amide I Band of Peptides Measured by Femtosecond Nonlinear-Infrared Spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102(31):6123–6138. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolano C, Helbing J, Kozinski M, Sander W, Hamm P. Watching Hydrogen-Bond Dynamics in a Beta-Turn by Transient Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy. Nature. 2006;444(7118):469–472. doi: 10.1038/nature05352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acharya KR, Lloyd MD. The Advantages and Limitations of Protein Crystal Structures. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson R. The Potential and Limitations of Neutrons, Electrons and X-Rays for Atomic-Resolution Microscopy of Unstained Biological Molecules. Q Rev Biophys. 1995;28(2):171–193. doi: 10.1017/s003358350000305x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-Free Approach to the Interpretation of Nuclear Magnetic-Resonance Relaxation in Macromolecules1 Theory and Range of Validity. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104(17):4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh A, Ostrander JS, Zanni MT. Watching Proteins Wiggle: Mapping Structures with Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy. Chem Rev. 2017;117(16):10726–10759. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YS, Hochstrasser RM. Applications of 2D IR Spectroscopy to Peptides, Proteins, and Hydrogen-Bond Dynamics. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113(24):8231–8251. doi: 10.1021/jp8113978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucker MJ, Abdo M, Courter JR, Chen JX, Brown SP, Smith AB, Hochstrasser RM. Nonequilibrium Dynamics of Helix Reorganization Observed by Transient 2D IR Spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(43):17314–17319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311876110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henzler-Wildman K, Kern D. Dynamic Personalities of Proteins. Nature. 2007:964–972. doi: 10.1038/nature06522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serrano AL, Waegele MM, Gai F. Spectroscopic Studies of Protein Folding: Linear and Nonlinear Methods. Protein Sci. 2012;21(2):157–170. doi: 10.1002/pro.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith JJ, Mccray JA, Hibberd MG, Goldman YE. Holmium Laser Temperature-Jump Apparatus for Kinetic-Studies of Muscle-Contraction. Rev Sci Instrum. 1989;60(2):231–236. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reppert M, Tokmakoff A. Computational Amide I 2D IR Spectroscopy as a Probe of Protein Structure and Dynamics. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2016;67(1):359–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040215-112055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamm P, Zanni MT. Concepts and Methods of 2d Infrared Spectroscopy. Cambridge University Pres; Cambridge; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanni MT, Asplund MC, Hochstrasser RM. Two-Dimensional Heterodyned and Stimulated Infrared Photon Echoes of N-Methylacetamide-D. J Chem Phys. 2001;114(10):4579–4590. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reppert M, Tokmakoff A. Electrostatic Frequency Shifts in Amide I Vibrational Spectra: Direct Parameterization against Experiment. J Chem Phys. 2013;138(13):134116. doi: 10.1063/1.4798938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith AW, Lessing J, Ganim Z, Peng CS, Tokmakoff A, Roy S, Jansen TLC, Knoester J. Melting of a Beta-Hairpin Peptide Using Isotope-Edited 2D IR Spectroscopy and Simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114(34):10913–10924. doi: 10.1021/jp104017h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anfinrud PA, Han CH, Lian T, Hochstrasser RM. Femtosecond Infrared Spectroscopy: Ultrafast Photochemistry of Iron Carbonyls in Solution. J Phys Chem. 1991;95(2):574–578. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dougherty TP, Grubbs WT, Heilweil EJ. Photochemistry of Rh(C0)2(acetylacetonate) and Related Metal Dicarbonyls Studied by Ultrafast Infrared Spectroscopy. J Phys Chem. 1994;98(38):9396–9399. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng JR, Kwak KW, Chen X, Asbury JB, Fayer MD. Formation and Dissociation of Intra–Intermolecular Hydrogen-Bonded Solute–Solvent Complexes: Chemical Exchange Two-Dimensional Infrared Vibrational Echo Spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(9):2977–2987. doi: 10.1021/ja0570584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng JR, Kwak KW, Xie J, Fayer MD. Ultrafast Carbon-Carbon Single-Bond Rotational Isomerization in Room-Temperature Solution. Science (80-) 2006;313(5795):1951–1955. doi: 10.1126/science.1132178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Sueur AL, Horness RE, Thielges MC. Applications of Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy. Analyst. 2015;140(13):4336–4349. doi: 10.1039/c5an00558b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bredenbeck J, Helbing J, Behrendt R, Renner C, Moroder L, Wachtveitl J, Hamm P. Transient 2D-IR Spectroscopy: Snapshots of the Nonequilibrium Ensemble during the Picosecond Conformational Transition of a Small Peptide. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107(33):8654–8660. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fenn EE, Fayer MD. Extracting 2D IR Frequency-Frequency Correlation Functions from Two Component Systems. J Chem Phys. 2011;135(7):74502 1–15. doi: 10.1063/1.3625278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stead RA, Mills AK, Jones DJ. Method for High Resolution and Wideband Spectroscopy in the Terahertz and Far-Infrared Region. J Opt Soc Am B-Optical Phys. 2012;29(10):2861–2868. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramos S, Scott KJ, Horness RE, Le Sueur AL, Thielges MC. Extended Timescale 2D IR Probes of Proteins: P-Cyanoselenophenylalanine. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2017;19(15):10081–10086. doi: 10.1039/c7cp00403f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin DE, Schmitz AJ, Hines SM, Hines KJ, Tucker MJ, Brewer SH, Fenlon EE. Synthesis and Evaluation of the Sensitivity and Vibrational Lifetimes of Thiocyanate and Selenocyanate Infrared Reporters. Rsc Adv. 2016;43(6):36231–36237. doi: 10.1039/C5RA27363C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamm P, Helbing J, Bredenbeck J. Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy of Photoswitchable Peptides. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2008;59(1):291–317. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt NT. Transient 2D-IR Spectroscopy of Inorganic Excited States. Dalt Trans. 2014;43(47):17578–17589. doi: 10.1039/c4dt01410c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hochstrasser RM. Two-Dimensional IR-Spectroscopy: Polarization Anisotropy Effects. Chem Phys. 2001;266(2–3):273–284. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bredenbeck J, Helbing J, Hamm P. Transient Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy: Exploring the Polarization Dependence. J Chem Phys. 2004;121(12):5943–5957. doi: 10.1063/1.1779575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bredenbeck J, Helbing J, Hamm P. Continuous Scanning from Picoseconds to Microseconds in Time Resolved Linear and Nonlinear Spectroscopy. Rev Sci Instrum. 2004;75(11):4462–4466. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore JN, Hansen PA, Hochstrasser RM. A New Method for Picosecond Time-Resolved Infrared-Spectroscopy - Applications to Co Photodissociation from Iron Porphyrins. Chem Phys Lett. 1987;138(1):110–114. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore JN, Hansen PA, Hochstrasser RM. Iron Carbonyl Bond Geometries of Carboxymyoglobin and Carboxyhemoglobin in Solution Determined by Picosecond Time-Resolved Infrared-Spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(14):5062–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baiz CR, Nee MJ, McCanne R, Kubarych KJ. Ultrafast Nonequilibrium Fourier-Transform Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy. Opt Lett. 2008;33(21):2533–2535. doi: 10.1364/ol.33.002533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bredenbeck J, Helbing J, Kolano C, Hamm P. Ultrafast 2D-IR Spectroscopy of Transient Species. ChemPhysChem. 2007;8(12):1747–1756. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200700148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metzler R, Klafter J, Jortner J, Volk M. Multiple Time Scales for Dispersive Kinetics in Early Events of Peptide Folding. Chem Phys Lett. 1998;293(5–6):477–484. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volk M, Kholodenko Y, Lu HSM, Gooding EA, DeGrado WF, Hochstrasser RM. Peptide Conformational Dynamics and Vibrational Stark Effects Following Photoinitiated Disulfide Cleavage. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101(42):8607–8616. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu HSM, Volk M, Kholodenko Y, Gooding E, Hochstrasser RM, DeGrado WF. Aminothiotyrosine Disulfide, an Optical Trigger for Initiation of Protein Folding. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119(31):7173–7180. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kolano C, Gomann K, Sander W. Small Cyclic Disulfide Peptides: Synthesis in Preparative Amounts and Characterization by Means of NMR and FT-IR Spectroscopy. European J Org Chem. 2004;(20):4167–4176. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kolano C, Helbing J, Bucher G, Sander W, Hamm P. Intramolecular Disulfide Bridges as a Phototrigger To Monitor the Dynamics of Small Cyclic Peptides. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111(38):11297–11302. doi: 10.1021/jp074184g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao XS, Miller WB, Hintsa EJ, Lee YT. A Concerted Triple Dissociation - the Photochemistry of S-Tetrazine. J Chem Phys. 1989;90(10):5527–5535. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tucker MJ, Courter JR, Chen JX, Atasoylu O, Smith AB, Hochstrasser RM. Tetrazine Phototriggers: Probes for Peptide Dynamics. Angew Chemie-International Ed. 2010;49(21):3612–3616. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King DS, Denny CT, Hochstrasser RM, Smith AB., III The Photochemical Decomposition of 1,4-S-Tetrazine-15N2. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99(1):271–273. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson PA, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. Laser Temperature Jump Study of the Helix-coil Kinetics of an Alanine Peptide Interpreted with a “Kinetic Zipper” Model. Biochemistry. 1997;36(30):9200–9210. doi: 10.1021/bi9704764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson PA, Munoz V, Jas GS, Henry ER, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. The Helix-Coil Kinetics of a Heteropeptide. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104(2):378–389. [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Sancho D, Sirur A, Best RB. Molecular Origins of Internal Friction Effects on Protein-Folding Rates. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4307. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hartley GS. The Cis-Form of Azobenzene. Nature. 1937;140(3537):281. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nagele T, Hoche R, Zinth W, Wachtveitl J. Femtosecond Photoisomerization of Cis-Azobenzene. Chem Phys Lett. 1997;272(5–6):489–495. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mart RJ, Allemann RK. Azobenzene Photocontrol of Peptides and Proteins. Chem Commun. 2016;52(83):12262–12277. doi: 10.1039/c6cc04004g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamm P, Ohline SM, Zinth W. Vibrational Cooling after Ultrafast Photoisomerization of Azobenzene Measured by Femtosecond Infrared Spectroscopy. J Chem Phys. 1997;106(2):519–529. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baiz CR, Reppert M, Tokmakoff A. Introduction to Protein 2D IR Spectroscopy. Ultrafast Infrared Vib Spectrosc. 2013:361–403. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pfister R, Ihalainen J, Hamm P, Kolano C. Synthesis, Characterization and Applicability of Three Isotope Labeled Azobenzene Photoswitches. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6(19):3508–3517. doi: 10.1039/b804568b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Backus EHG, Bloem R, Donaldson PM, Ihalainen JA, Pfister R, Paoli B, Caflisch A, Hamm P. 2D-IR Study of a Photoswitchable Isotope-Labeled Alpha-Helix. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114(10):3735–3740. doi: 10.1021/jp911849n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ihalainen JA, Bredenbeck J, Pfister R, Helbing J, Chi L, van Stokkum IHM, Woolley GA, Hamm P. Folding and Unfolding of a Photoswitchable Peptide from Picoseconds to Microseconds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(13):5383–5388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607748104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bredenbeck J, Helbing J, Kumita JR, Woolley GA, Hamm P. Alpha-Helix Formation in a Photoswitchable Peptide Tracked from Picoseconds to Microseconds by Time-Resolved IR Spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(7):2379–2384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406948102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hansen KC, Rock RS, Larsen RW, Chan SI. A Method for Photoinitating Protein Folding in a Nondenaturing Environment. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122(46):11567–11568. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kubelka J. Time-Resolved Methods in Biophysics 9 Laser Temperature-Jump Methods for Investigating Biomolecular Dynamics. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2009;8(4):499–512. doi: 10.1039/b819929a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beitz JV, Flynn GW, Turner DH, Sutin N. Stimulated Raman Effect - a New Source of Laser Temperature-Jump Heating. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92(13):4130–4132. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ameen S, De Maeyer L. Stimulated Raman-Scattering from Molecular Hydrogen Gas for Fast Heating in Laser-Temperature-Jump Chemical Relaxation Experiments. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97(6):1590–1591. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williams AP, Longfellow CE, Freier SM, Kierzek R, Turner DH. Laser Temperature-Jump, Spectroscopic, and Thermodynamic Study of Salt Effects on Duplex Formation by dGCATGC. Biochemistry. 1989;28(10):4283–4291. doi: 10.1021/bi00436a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chung HS, Ganim Z, Jones KC, Tokmakoff A. Transient 2D IR Spectroscopy of Ubiquitin Unfolding Dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(36):14237–14242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700959104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang XX, Jones KC, Fitzpatrick A, Peng CS, Feng CJ, Baiz CR, Tokmakoff A. Studying Protein-Protein Binding through T-Jump Induced Dissociation: Transient 2D IR Spectroscopy of Insulin Dimer. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120(23):5134–5145. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b03246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma H, Wan C, Zewail AH. Ultrafast T-Jump in Water: Studies of Conformation and Reaction Dynamics at the Thermal Limit. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(19):6338–6340. doi: 10.1021/ja0613862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nolting B. Distribution of Temperature in Globular Molecules, Cells, or Droplets in Temperature-Jump, Sound Velocity, and Pulsed LASER Experiments. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102(38):7506–7509. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Phillips CM, Mizutani Y, Hochstrasser RM. Ultrafast Thermally-Induced Unfolding of Rnase-A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(16):7292–7296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rusconi R, Isa L, Piazza R. Thermal-Lensing Measurement of Particle Thermophoresis in Aqueous Dispersions. J Opt Soc Am B-Optical Phys. 2004;21(3):605–616. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murphy KP. Protein Structure, Stability, and Folding. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chung HS, Khalil M, Smith AW, Ganim Z, Tokmakoff A. Conformational Changes during the Nanosecond-to-Millisecond Unfolding of Ubiquitin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(3):612–617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408646102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weber JK, Jack RL, Pande VS. Emergence of Glass-like Behavior in Markov State Models of Protein Folding Dynamics. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(15):5501–5504. doi: 10.1021/ja4002663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jones KC, Peng CS, Tokmakoff A. Folding of a Heterogeneous Beta-Hairpin Peptide from Temperature-Jump 2D IR Spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(8):2828–2833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211968110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chung HS, Khalil M, Smith AW, Tokmakoff A. Transient Two-Dimensional IR Spectrometer for Probing Nanosecond Temperature-Jump Kinetics. Rev Sci Instrum. 2007;78(6):63101 1–10. doi: 10.1063/1.2743168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ganim Z, Chung HS, Smith AW, Deflores LP, Jones KC, Tokmakoff A. Amide I Two-Dimensional Infrared Spectroscopy of Proteins. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41(3):432–441. doi: 10.1021/ar700188n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barth A. The Infrared Absorption of Amino Acid Side Chains. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2000;74(3–5):141–173. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee H, Choi JH, Cho M. Vibrational Solvatochromism and Electrochromism of Cyanide, Thiocyanate, and Azide Anions in Water. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12(39):12658–12669. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00214c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chung JK, Thielges MC, Fayer MD. Dynamics of the Folded and Unfolded Villin Headpiece (HP35) Measured with Ultrafast 2D IR Vibrational Echo Spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(9):3578–3583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100587108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Getahun Z, Huang CY, Wang T, De Leon B, DeGrado WF, Gai F. Using Nitrile-Derivatized Amino Acids as Infrared Probes of Local Environment. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(2):405–411. doi: 10.1021/ja0285262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McMahon HA, Alfieri KN, Clark KAA, Londergan CH. Cyanylated Cysteine: A Covalently Attached Vibrational Probe of Protein-Lipid Contacts. J Phys Chem Lett. 2010;1(5):850–855. doi: 10.1021/jz1000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gai XS, Coutifaris BA, Brewer SH, Fenlon EE. A Direct Comparison of Azide and Nitrile Vibrational Probes. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13(13):5926–5930. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02774j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tucker MJ, Gai XS, Fenlon EE, Brewer SH, Hochstrasser RM. 2D IR Photon Echo of Azido-Probes for Biomolecular Dynamics. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13(6):2237–2241. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01625j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Manor J, Mukherjee P, Lin YS, Leonov H, Skinner JL, Zanni MT, Arkin IT. Gating Mechanism of the Influenza A M2 Channel Revealed by 1D and 2D IR Spectroscopies. Structure. 2009;17(2):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koziol KL, Johnson PJM, Stucki-Buchli B, Waldauer SA, Hamm P. Fast Infrared Spectroscopy of Protein Dynamics: Advancing Sensitivity and Selectivity. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2015:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]