Abstract

Zn-porphyrin is a promising organic photosensitizer in various fields including solar cells, interface and biomedical research, but the biosynthesis study has been limited, probably due to the difficulty of understanding complex biosynthesis pathways. In this study, we developed a Corynebacterium glutamicum platform strain for the biosynthesis of Zn-coproporphyrin III (Zn-CP III), in which the heme biosynthesis pathway was efficiently upregulated. The pathway was activated and reinforced by strong promoter-induced expression of hemAM (encoding mutated glutamyl-tRNA reductase) and hemL (encoding glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase) genes. This engineered strain produced 33.54 ± 3.44 mg/l of Zn-CP III, while the control strain produced none. For efficient global regulation of the complex pathway, the dtxR gene encoding the transcriptional regulator diphtheria toxin repressor (DtxR) was first overexpressed in C. glutamicum with hemAM and hemL genes, and its combinatorial expression was improved by using effective genetic tools. This engineered strain biosynthesized 68.31 ± 2.15 mg/l of Zn-CP III. Finally, fed-batch fermentation allowed for the production of 132.09 mg/l of Zn-CP III. This titer represents the highest in bacterial production of Zn-CP III reported to date, to our knowledge. This study demonstrates that engineered C. glutamicum can be a robust biotechnological model for the production of photosensitizer Zn-porphyrin.

Introduction

Porphyrins functioning as photo-electrochemical materials are of particular interest in a range of areas related to solar cell technology, battery chemistry, solid/liquid interfaces and biomedical research because of their functional and structural properties that incorporate a metal ion in the center and have great absorption bands in the visible spectrum1–7. In particular, Zn-porphyrin derivatives have recently attracted much attention for their great potential application as a promising raw material for sensitizing an organic solar cell in a photovoltaic system that harvests light to convert solar energy into electricity, or in catalyzing multistep reactions at interface3,4,8–13. In addition to electronic and physicochemical applications, Zn-porphyrins have been studied as photosensitizers for their antitumor and antibacterial activity in photodynamic therapy-mediated biomedical applications14. Furthermore, iron-porphyrin has been used to synthesize bio-based magneto-electric nanocrystals by the heme polymerase enzyme complex and demonstrated as a monomer for advanced nanomaterial synthesis15. Most porphyrins used in applications are commonly synthesized from chemical reactions, which have also made great efforts for the high yieldable, cost-efficient and eco-friendly process16–18.

Bio-based production of a useful compound is an attractive and alternative route to be able to yield high production levels through a microbial cell factory using a renewable, cost-efficient and eco-friendly source such as glucose. The biological synthesis for important biochemical compounds has recently attracted much attention in various scientific fields such as biotechnology, biomedical, chemical engineering and environmental science19–22. However, biosynthesis researches for most porphyrins were rarely reported until recently. In living organisms, porphyrins are commonly biosynthesized through the long and complex heme biosynthesis pathway regulated by eight to nine enzymes. This biosynthesis is initiated from the enzymatic condensation of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) as a common precursor to yield porphobilinogen (PBG). After that, coproporphyrin III (CP III) or protoporphyrin (PP IX), acting as a chassis for various metallated porphyrin derivatives, is biosynthesized from PBG by five or six enzymatic reactions23. Metallated porphyrins have various biological and physiological functions. Heme functions as an enzymatic cofactor and electron transfer, chlorophyll is used in photosynthesis, and CP III is an element carrier via chelation of certain metal ions24,25.

Corynebacterium glutamicum, a gram-positive, nonpathogenic and facultative anaerobic organism, has been frequently used and developed for large-scale production of a variety of amino acids such as l-glutamate and l-lysine, proteins, and monomers for various chemical compounds from renewable biomass26–31. Recently, we reported that the engineered C. glutamicum produced ALA, a precursor in the heme biosynthesis pathway32,33. ALA biosynthesis in almost all bacteria containing Escherichia coli and C. glutamicum is the rate-limiting step in the heme biosynthesis pathway34–36. Hence, ALA biosynthesis has been overcome by two different approaches: 1) engineering of the C5 pathway initiated from l-glutamate or 2) engineering of the C4 pathway initiated from succinyl-CoA with glycine34–36. The C5 pathway is processed by three enzymes including glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (encoded by the gltX gene) producing l-glutamyl-tRNA from l-glutamate, glutamyl-tRNA reductase (encoded by the hemA gene) reducing l-glutamyl-tRNA to glutamate-1-semialdehyde, and glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase (encoded by the hemL gene) biosynthesizing ALA from glutamate-1-semialdehyde by transamination25. The C4 pathway is processed by the ALA synthase (encoded by the alaS gene) biosynthesizing ALA from succinyl-CoA with glycine25. Unlike studies about ALA biosynthesis, as mentioned above, there are only a few studies on the biosynthesis of a porphyrin in bacteria37–39. Porphyrin overproduction containing heme, PP IX and/or CP III has been reported in metabolically engineered E. coli via overexpression of a number of genes related to the heme biosynthesis pathway through several vectors37,38. In the case of C. glutamicum, porphyrin production has only been reported as an iron additive for heme production by expressing ALA synthase39. In particular, study on the biosynthesis of Zn-porphyrin has been rarely reported, and none reported Zn-porphyrin production in a genetically engineered strain24,40.

The heme biosynthesis pathway is long, complicated, and tightly regulated by various factors such as feedback inhibition by the final product and repression of gene expression by the transcriptional regulator23,25,41–43. In recent years, transcriptional regulation related to iron and heme homeostasis have been studied in C. glutamicum43–47. It was revealed that the global transcriptional regulator called diphtheria toxin repressor (DtxR) controlled the expression of genes encoding a variety of membrane protein and transcriptional regulators involved in iron storage, uptake and utilization. In particular, it has been confirmed that heme and iron metabolism are closely involved with each other for homeostasis and are tightly regulated by DtxR protein under conditions dependent on iron concentration43,45,47. In addition, it has revealed that the heme responsive regulator activator HrrA (encoded by the hrrA gene) repressed the transcription of partial genes included in heme operon43. Indeed, when the hrrA gene, repressed by the DtxR protein, was deleted from the genome of C. glutamicum, the mRNA expression level of partial heme biosynthesis-related genes was upregulated43. However, the cell growth of the hrrA gene deletion strain was significantly decreased. The direct impact of the DtxR protein for porphyrin production on the control of heme metabolism has not been studied43.

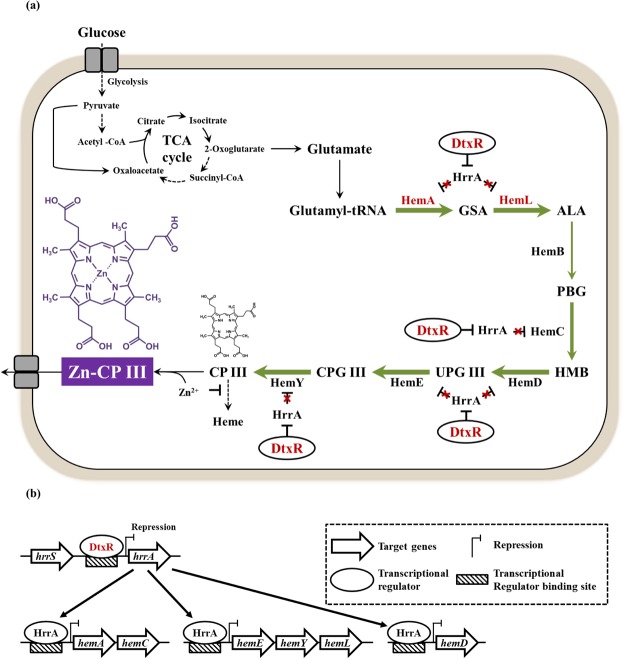

In this study, we describe the establishment of the C. glutamicum platform strain overproducing Zn-CP III and other porphyrins using metabolic engineering for the first time, to our knowledge. We selected C. glutamicum as a host strain for Zn-porphyrin production in this study, because this strain overproduces l-glutamate as a starting material in the heme biosynthesis pathway and is a well-developed ALA producer in our previous study32. Metabolic engineering for the increased production of Zn-CP III requires enhanced metabolic flux from various metabolites toward coproporphyrin III. Strategies for the enhancement of Zn-CP III production were designed to activate and upregulate the heme biosynthesis pathway and are pictured in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1. The strategy for activating the heme biosynthesis pathway is the overexpression of hemAM (mutated hemA) and hemL and is reinforced by expressing two genes under the control of a strong promoter. Following this strategy, to achieve the global upregulation of heme operons (Fig. 1b), we first overexpressed DtxR protein into C. glutamicum with HemAM and HemL proteins. The combinatorial expression of target genes by effective genetic tools achieved the significant decrease of mRNA expression of the hrrA gene, the substantial increase of mRNA expression of heme biosynthesis-related genes, and the highest production of Zn-CP III over engineered strains. Finally, we successfully achieved the biosynthesis of Zn-CP III in fed-batch fermentation supplemented with a zinc source. This study demonstrates that engineered C. glutamicum has potential industrial applications as a platform for Zn-porphyrin production.

Figure 1.

A schematic overview describing the target pathway and overall metabolic strategies for Zn-porphyrin production in C. glutamicum. (a) The heme biosynthesis pathway used in this study. Glucose indicates a major sole energy source used in this study for cell growth and porphyrin production. Glycolysis starting from glucose is a chain of reactions to form pyruvate, which enters tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle with acetyl-CoA. TCA cycle is a series of biochemical reactions providing essential biochemical intermediates, such as 2-oxoglutarate, succinyl-CoA, etc., for cellular energy production and amino acid biosynthesis containing l-glutamate and l-glycine. Zinc-porphyrin biosynthesis is initiated from l-glutamate. The red letter represents the gene overexpression in C. glutamicum. The T-shape and red X-shape denote the gene repression by the transcriptional regulator and inactivation of the HrrA protein by gene repression by the DtxR protein, respectively. The solid-line arrow and dashed-line arrow indicate the general metabolic pathway and abbreviated metabolic pathway, respectively. The green arrow denotes enhanced metabolic flux by the combinatorial overexpression of hemAM, hemL and dtxR genes. The width of each green arrow is proportional to the result of the mRNA expression level of heme biosynthesis genes when the DtxR protein was overexpressed with HemAM and HemL protein. Purple and black colored chemicals are the target product Zn-CP III and porphyrin chassis CP III, respectively. (b) The regulatory mechanism of the transcriptional regulator DtxR in C. glutamicum. The DtxR protein and HrrA protein bind in the promoter region in front of target genes, respectively, repress the gene expression of those43,45,47. Major symbols were described in the dashed black line box. The black line arrow shows processing of regulatory mechanisms of the HrrA protein. Abbreviations: GSA, l-glutamate 1-semialdehyde; ALA, 5-aminolevulinic acid; PBG, porphobilinogen; HMB, hydroxymethylbilane; UPG III, uroporphyrinogen III; CPG III, coproporphyrinogen III; CP III, coproporphyrin III; Zn-CP III, zinc-coproporphyrin III; UP III, uroporphyrin III; HemA, glutamyl-tRNA reductase; HemL, glutamate-1-semialdehyde 2,1-aminomutase; HemB, porphobilinogen synthase; HemC, hydroxymethylbilane synthase; HemD, uroporphyrinogen-III synthase; HemE, uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase; HemY, coproporphyrinogen III oxidase; DtxR, diphtheria toxin repressor; HrrA, heme responsive regulator activator.

Results

Enhanced activation of the heme biosynthesis pathway by the expression of hemAM and hemL genes under the strong tac promoter

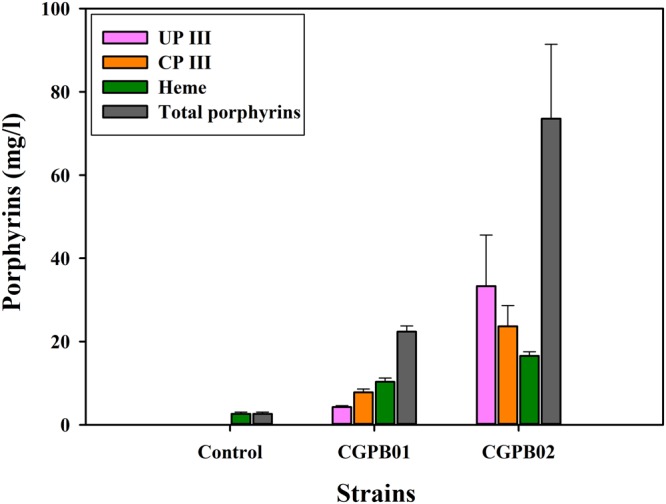

ALA production is an important first step for enhanced production of porphyrin derivatives because almost all porphyrins are commonly biosynthesized in the heme biosynthesis pathway using eight molecules of ALA as the precursor25. We previously confirmed the potential of engineered C. glutamicum as an ALA-producing strain that coexpressed mutated hemA (derived from Salmonella typhimurium) and hemL (derived from E. coli) genes by the expression vector pMT-trc containing the trc-derived promoter and pCG1 origin of replication, named the pHemAL vector(pMT-trc::hemAML throughout this article)32. In this study, to investigate its potential as a strain for the production of ALA and porphyrins, the engineered strain harboring the pMT-trc::hemAML vector was tested. Furthermore, for strong expression of target genes, hemAM and hemL genes were cloned in the other expression vector pMT-tac replacing trc-derived promoter with the strong tac promoter (Supplementary Fig. S1). To analyze metabolites produced, the control strain harboring the empty vector and engineered C. glutamicum strains harboring the pMT-trc::hemAML and pMT-tac::hemAML vectors (named CGPB01 and CGPB02 throughout this article, respectively) were cultivated in modified CGXII medium, adding penicillin G at 12 h for l-glutamate overproduction. Compared with the CGPB01 strain, which produced 338.85 ± 5.44 mg/l of ALA, the CGPB02 strain showed a 1.77-fold increase in the ALA production, corresponding to 600.79 ± 62.47 mg/l of ALA after 72 h of cultivation (Supplementary Fig. S2). Furthermore, while the control strain showed no production of any porphyrins except heme, the CGPB02 strain produced 33.32 ± 12.26 mg/l of uroporphyrin III (UP III), 23.68 ± 4.98 mg/l of CP III, and 16.56 ± 0.98 mg/l of heme, which was 7.79-fold, 3.04-fold, and 1.61-fold more than the CGPB01 strain, respectively (Fig. 2). Additionally, 22.38 ± 1.37 and 73.56 ± 17.89 mg/l of total porphyrins were produced in CGPB01 and CGPB02, respectively. Maximum cell growth was not affected by the expression of hemAM and hemL genes under the tac promoter (Supplementary Fig. S2). This result indicates that the expression of hemAM and hemL genes is important for activation of the heme biosynthesis pathway in C. glutamicum, and the expression under the tac promoter was strong enough to increase the metabolic flux of the heme biosynthesis pathway compared with the trc-derived promoter.

Figure 2.

Porphyrin production characteristics of the control, CGPB01 and CGPB02 strains after 72 h of shake-flask cultivation. The x-axis and y-axis represent engineered strains and the titer of porphyrin produced, respectively. The cultivation of all engineered strains was conducted in triplicate, and all data and error bars denote mean values of three independent experiments and standard deviations of mean values, respectively.

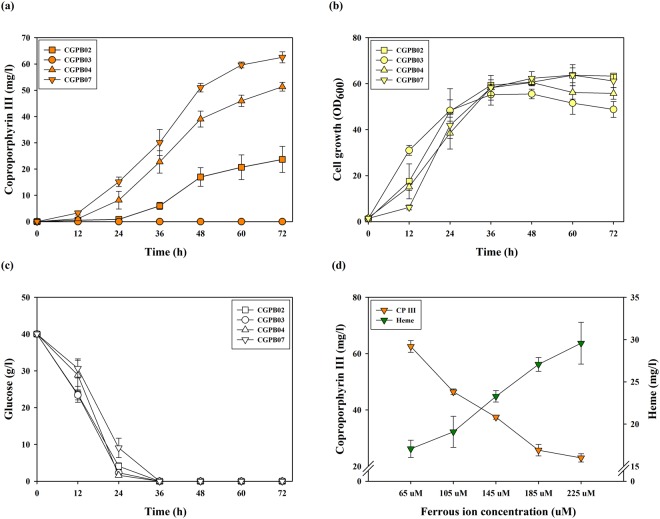

Enhanced metabolic flux toward a porphyrin chassis CP III by the combinatorial expression of the hemAM, hemL and dtxR genes

In this study, we selected CP III as a final chassis for Zn-porphyrin biosynthesis. It has been revealed that not only CP III acted as a chelate of zinc, but also Zn-CP III was biosynthesized from CP III produced in bacteria including wild type Paracoccus denitrificans and Streptomyces sp. in culture medium supplemented with zinc sulfate24,40. As mentioned above, the transcription regulation mechanism between partial heme operon and the HrrA protein in C. glutamicum has been studied, although the cell growth of the hrrA gene deletion strain was significantly decreased43,45. Hence, we hypothesized that the DtxR protein may serve as an effective enhancer of the heme biosynthesis pathway. To verify this hypothesis, the dtxR gene (derived from C. glutamicum) encoding the DtxR protein was introduced into the control strain and the CGPB02 strain, named the CGPB03 and CGPB04 strains, respectively. Contrary to expectations, while the production of CP III and UP III in the CGPB03 strain was not detected, the CGPB04 strain showed a 1.82-fold and 2.17-fold increase (60.90 ± 3.26 and 51.35 ± 1.69 mg/l) of UP III and CP III production over the CGPB02 strain, respectively (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. S3). Although the overexpression of the hemAM and hemL genes somewhat delayed the exponential growth phase, whether or not the dtxR gene was present, the maximum cell growth and glucose consumption were not affected (Fig. 3b,c). These results show that the combinatorial expression of dtxR with hemAM and hemL not only overcomes the rate-limiting step but also improves CP III production by enhancing the metabolic flux of the heme biosynthesis pathway without the critical negative effect of cell growth.

Figure 3.

Production and growth characteristics of the CGPB02, CGPB03, CGPB04, and CGPB07 strains during 72 h of shake-flask cultivation. (a) CP III production in engineered strains. The x-axis and y-axis represent time and the titer of CP III produced, respectively. (b) Cell growth of engineered strains. The x-axis and y-axis denote time and OD600, respectively. (c) Glucose consumption of engineered strains. The x-axis and y-axis indicate time and glucose concentration in the medium, respectively. (d) CP III and heme production in the CGPB07 strain in the culture condition of various iron sulfate concentrations. The x-axis, left y-axis and right y-axis represent the iron sulfate concentration and titer of CP III and heme produced, respectively. The cultivation of all engineered strains was conducted in triplicate, and all data and error bars denote mean values of three independent experiments and standard deviations of mean values, respectively. Symbols: square, CGPB02 strain; circle, CGPB03 strain; triangle, CGPB04 strain; inverted triangle, CGPB07 strain; orange color, CP III production; green color, heme production; yellow color, cell growth; white color, glucose.

To enhance the metabolic flux of the heme biosynthesis pathway toward CP III, the hemAM, hemL and dtxR genes were additionally cloned in an E. coli-C. glutamicum shuttle vector pEKEx2 containing the tac promoter and pBL1 origin of replication. A pBL1 origin of replication contained in Shuttle vector pEKEx2 shows 8–30 copy numbers per cell, and a pCG1 origin of replication contained in pMT-tac shows 13–22 copy numbers per cell48,49. Expression of the hemAM, hemL and dtxR genes using the pEKEx2 vector was more effective at producing CP III than using the pMT-tac vector. Compared with the CGPB04 strain, the engineered strain harboring pEKEx2::hemAMLdtxR (named the CGPB07 strain herein) showed a 1.22-fold increase in CP III production, corresponding to 62.54 ± 2.09 mg/l (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, UP III production in the CGPB07 strain was decreased 1.55-fold compared to the CGPB04 strain (Supplementary Fig. S3). The result means that the metabolic flux from UP III to CP III may be extended by the reinforced expression of hemAM, hemL and dtxR genes through the pEKEx2 vector. Therefore, the CGPB07 strain is more useful for Zn-CP III production compared to other engineered strains.

The DtxR protein uses two ferrous iron as an essential cofactor45. Hence, cultivation with various concentrations of iron was performed on the CGPB04 and CGPB07 strains for enhanced production of CP III. However, along with increasing the iron concentration, CP III production in both the CGPB04 and CGPB07 strains decreased constantly while heme production was increased (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. S4). These results mean that ferrous iron added in the culture medium may be used in processes to biosynthesize heme from CP III.

Global upregulation of the heme biosynthesis pathway by the transcriptional regulator DtxR

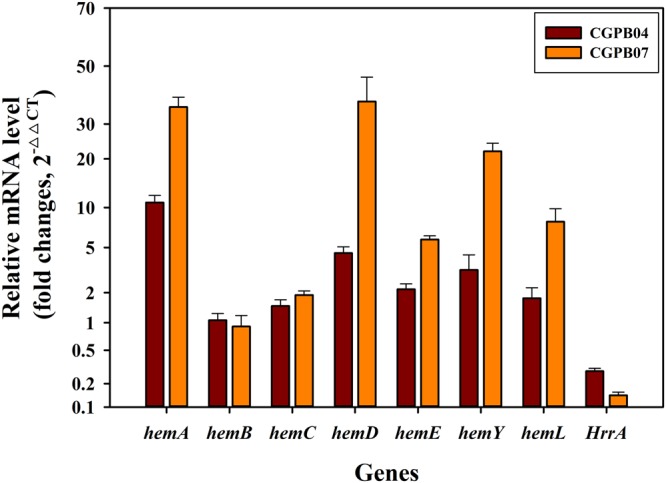

It has been reported that the mRNA expression level of hemA, hemC (encoding porphobilinogen deaminase), hemE (encoding uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase), hemY (encoding protoporphyrinogen oxidase) and hemL was decreased when the hrrA gene was deleted in C. glutamicum43. However, transcriptional analysis of hemB and hemD (encoding uroporphyrinogen-III synthase) genes in the hrrA gene deletion strain as well as the transcriptional regulation of the heme biosynthesis pathway by the overexpression of the DtxR protein has not been studied yet. In particular, the DtxR protein has never been used for porphyrins production, to our knowledge. To investigate the positive effect of the DtxR protein in enhancing the metabolic flux of the heme biosynthesis pathway, we analyzed the relative mRNA expression of heme biosynthesis-related genes when the DtxR protein was overexpressed. Compared to the CGPB02 strain, the mRNA expression levels of the hemA, hemL, hemC, hemD, hemE and hemY genes in the genome directly involved in CP III production after the precursor synthesis were all increased in the CGPB04 strain, which showed 10.83 ± 1.21-, 1.77 ± 0.46-, 1.48 ± 0.22-, 4.50 ± 0.55-, 2.15 ± 0.27- and 3.23 ± 1.19-fold increases respectively (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the mRNA expression level of the hrrA gene in the CGPB04 strain was significantly decreased 0.28 ± 0.02-fold over the CGPB02 strain. However, the hemB mRNA expression level did not change, and this result means that the hemB gene may not be regulated by the HrrA protein. Taken together, these data indicate that genes related to the heme biosynthesis pathway were mostly upregulated by hrrA gene repression via overexpression of the DtxR protein, which may result in increasing the total porphyrin production in the engineered strain. In addition, the mRNA expression levels of the hemA, hemL, hemC, hemD, hemE and hemY genes in the CGPB07 strain were more increased than those of the CGPB04 strain, and showed the 35.55 ± 3.37-, 1.89 ± 0.18-, 37.40 ± 8.58-, 5.79 ± 0.41-, 22.02 ± 2.20- and 7.92 ± 1.88-fold increase over the CGPB02 strain, respectively. The hrrA mRNA expression level in the CGPB07 strain was more decreased than that of the CGPB04 strain, showed the 0.14 ± 0.01-fold decrease over the CGPB02 strain. The result means that the mRNA expression of heme biosynthesis-related genes may be improved by the hrrA gene repression by the improved expression of the DtxR protein through the pEKEx2 vector.

Figure 4.

The analysis of mRNA expression levels of porphyrin biosynthesis related-genes in the CGPB02, CGPB04 and CGPB07 strains by qRT-PCR. To analyze mRNA expression levels of target genes, all engineered strains were incubated in CGXII medium with 4% glucose for 12 h. Relative mRNA expression levels of hemA, hemL, hemB, hemC, hemD, hemE, hemY, and hrrA, measured in the CGPB04 and CGPB07 strains, were compared with those of the CGPB02 strain. The 16 S rRNA level in all engineered strains was used as an internal reference for normalization. The mRNA analysis of all engineered strains was conducted in triplicate, and all data and error bars represent mean values of three independent experiments and standard deviations of mean values, respectively.

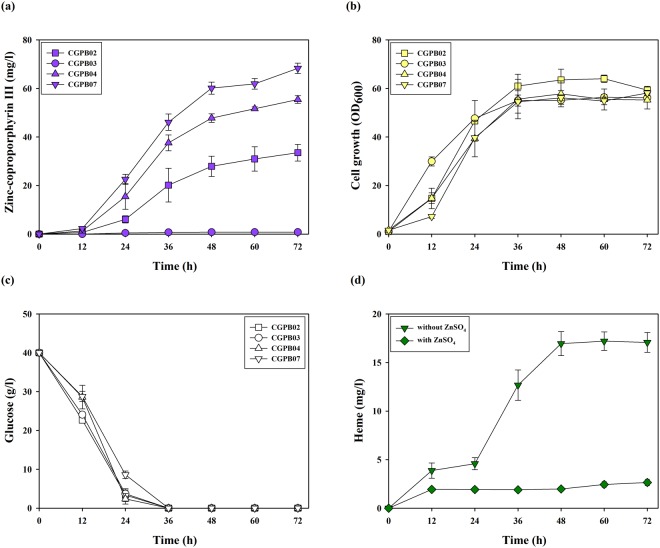

Zn-CP III biosynthesis by engineered C. glutamicum strains by the combinatorial expression of the hemAM, hemL and dtxR genes

For Zn-CP III production, CP III-producing engineered strains were shake-cultivated in a glucose-minimal medium supplemented with zinc sulfate for 72 h, and most engineered strains except for the CGPB03 strain successfully produced Zn-CP III (Fig. 5a). Compared with the CGPB02 strain that produced 33.54 ± 3.44 mg/l of Zn-CP III, the CGPB04 and CGPB07 strains showed 1.65- and 2.04-fold increases in Zn-CP III production, corresponding to 55.44 ± 1.58 and 68.31 ± 2.15 mg/l, respectively. Similarly, as in the case of CP III, the CGBP07 strain showed the highest titer of Zn-CP III in bacteria reported to date, and the growth pattern and glucose consumption of all engineered strains were rarely affected (Fig. 5b,c).

Figure 5.

Production and growth characteristics of the CGPB02, CGPB03, CGPB04, and CGPB07 strains during 72 h of shake-flask cultivation supplemented with zinc sulfate. (a) Zn-CP III production in engineered strains. The x-axis and y-axis represent time and the titer of Zn-CP III produced, respectively. (b) Cell growth of engineered strains. The x-axis and y-axis denote time and OD600, respectively. (c) Glucose consumption of engineered strains. The x-axis and y-axis indicate time and glucose concentration in the medium, respectively. (d) Comparison of heme production in the culture with and without zinc sulfate in the CGPB07 strain. The x-axis and y-axis represent time and titer of heme produced, respectively. The cultivation of all engineered strains was conducted in triplicate, and all data and error bars denote mean values of three independent experiments and standard deviations of mean values, respectively. Symbols: square, CGPB02 strain; triangle, CGPB04 strain; inverted triangle or diamond (in result supplemented with zinc sulfate), CGPB07 strain; purple color, Zn-CP III production; green color, heme production; yellow color, cell growth; white color, glucose.

Interestingly, relative to the total titer of CP III produced in the CGPB07 strain cultured without zinc sulfate, the total titer of Zn-CP III produced in the strain cultured with zinc sulfate was increased to 68.31 ± 2.15 mg/l from 62.54 ± 2.09 mg/l of CP III without certain genetic modifications, corresponding to a further 4.4% increase (Figs 3a, 5a). On the other hand, the total titer of heme produced in the strain cultured with zinc sulfate was decreased compared to that produced in the strain cultured without zinc sulfate, from 17.08 ± 0.10 mg/l to 2.64 ± 0.32 mg/l (Fig. 5d). This result means that CP III was partially used in Zn-CP III production rather than in heme production. The absorption spectrum of metabolites produced in the CGPB07 strain when zinc sulfate was supplemented showed not only the strongest feature at 406 nm but also minor features at 538 and 574 nm, representing optical characteristics of Zn-CP III (Supplementary Fig. S5) similar to that of previous studies24,40. Typically, CP III has a maximum Soret band at 393 nm, consistent with the absorption maximum of metabolites produced in the strain cultured without zinc sulfate. These results suggest that engineered C. glutamicum strains successfully produced Zn-CP III, and efficiently used robust porphyrin metabolism to biosynthesize Zn-CP III.

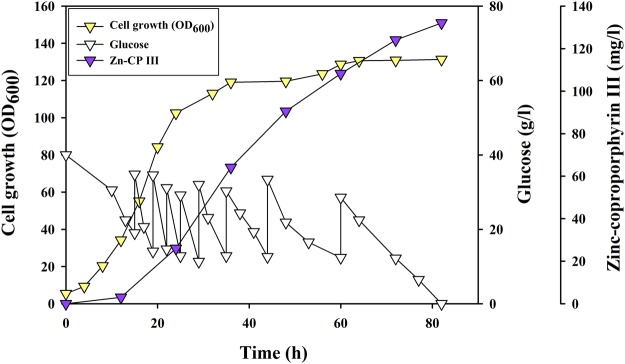

Fed-batch fermentation for enhanced biosynthesis of Zn-CP III in engineered C. glutamicum

To test the potential of the CGPB07 strain for large-scale production of Zn-CP III, we carried out 1.8- l fed-batch fermentation in a 5 l fermenter (Fig. 6). Glucose feeding was initiated after 15 h of fermentation and was additionally injected whenever the glucose concentration was below 20 g/l. During fed-batch fermentation of the CGPB07 strain, the maximum titer reached 132.09 mg/l of Zn-CP III in 82 h of fermentation in which the total input of glucose was 350.5 g. The overall yield and productivity were 1.27 mg/g glucose and 1.61 mg/l/h, respectively. The specific growth rate in the exponential growth phase (between 8 and 20 h) was 0.12/h. The maximum OD600 was 131.33, corresponding to the measured cell biomass of 37.04 g/l at the end of fermentation.

Figure 6.

The fed-batch fermentation profile of the CGPB07 strain for Zn-CP III production. The x-axis, left y-axis, right y-axis, and right y-offset denote time, OD600, glucose, and Zn-CP III produced, respectively. Symbols: inverted triangle, CGPB07 strain; purple color, Zn-CP III production; yellow color, cell growth; white color, glucose.

Discussion

Much research has recently advanced Zn-porphyrin and porphyrin derivatives as promising raw material for solar cell devices, solid/liquid interface and photodynamic therapy over the past several years1–6. Until now, the development of porphyrin production in bacteria has lagged behind precursor ALA production presumably because of the complex synthetic processes and regulatory mechanisms of the heme biosynthetic pathway. Toriya et al. found that wild type Streptomyces sp. strain AC8007 biosynthesizes Zn-CP III (10 mg/l), but there was no metabolic design for overproduction of Zn-CP III in this wild type strain40. Kwon et al. reported successful production of CP III, PP IX and heme (89 ± 9 μmol/l of total porphyrins, corresponding to approximately 50 mg/l of total porphyrins) in E. coli by overexpressing eight genes related to heme biosynthesis37. However, the introduction of many genes and vectors may require excessive use of antibiotic resistance markers and reduce cell growth by metabolic burden50. Indeed, engineered E. coli strains, named as the ECPB01, ECPB02 and ECPB03 strains, less produced Zn-CP III than engineered C. glutamicum strains, corresponding to 1.93 ± 0.05 mg/l, 1.87 ± 0.07 mg/l and 1.84 ± 0.05 mg/l, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S6). The porphyrin production in the engineered E. coli strain overexpressing the HemAM and HemL proteins (C5 pathway) in this study was similar to that in the engineered strain overexpressing the ALA synthase (C4 pathway) used in the study of Kwon et al.37. Furthermore, the DtxR protein only worked in C. glutamicum, but not in E. coli (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Figs S3, S6). This result means that C. glutamicum is suitable for Zn-CP III and have the possibility of performing the further metabolic engineering. In the field of microbial engineering, pertinent gene expression and regulation of the target biosynthesis pathway are important factors for high-yield production of a target product51. In this study, we confirmed the potential of C. glutamicum as a platform strain for Zn-CP III and porphyrin production. The activation and upregulation of the long and complex heme biosynthesis pathway by the transcriptional regulator DtxR alongside HemAM and HemL proteins in C. glutamicum can allow for efficient biosynthesis of Zn-CP III. Furthermore, target gene expression by the efficient genetic tool such as replacement of the strong promoter and origin of replication achieved the high production of CP III, Zn-CP III and Heme. Furthermore, the mRNA expression of most heme biosynthesis genes except for the hemB gene was significantly improved in the CGPB07 strain (Fig. 4). Interestingly, while the hemD gene, which is located at 500-bp upstream of the hemB gene, was upregulated by the hrrA gene repression, the hemB gene expression was not affected in both the CGPB04 and CGPB07 strains. Even though the hemB gene is close to the hemD gene in genome, their expression may be regulated by different expression factors containing a promoter and repressor because it is predicted that they do not exist as an operon (an operon was predicted at http://www.coryneregnet.de/)43. Based on these results, It can be speculated that hemB and hemD genes are individually expressed by different factors and that there exists no binding site for the HrrA protein in the promoter region of the hemB gene. Frunzke et al. has identified that the HrrA protein bound in the promoter region of hemA and hemE genes although the promoter region of hemD and hemB genes remained unclear43. Nonetheless, the enhanced mRNA expression level of most heme biosynthesis genes by the combinatorial expression of hemAM, hemL and dtxR genes induced substantial porphyrin production (Figs 3a, 4, Supplementary Fig. S3). Interestingly, in the CGPB03 strain overexpressing the dtxR gene alone, most of the porphyrins except for heme were not produced (Supplementary Fig. S3). We suggest the reason may be because the native HemA protein overexpressed by the DtxR protein is feedback-inhibited by the final product heme41–43.

In terms of the insertion of a zinc ion into metal-free porphyrin, CP III may be more suitable for Zn-porphyrin synthesis than PP IX because CP III has the characteristic of spontaneous chelation of a zinc ion without any energy requirement while PP IX requires an enzyme reaction for Zn-PP IX biosynthesis24,52,53. Indeed, as described in our results regarding CP III, Zn-CP III and heme concentration, CP III generated for subsequent biosynthesis pathways was used for Zn-CP III production instead of heme production (Figs 3, 5). Dailey et al. recently revealed that the Actinobacteria and Firmicutes uses CP III instead of PP IX in heme biosynthesis54. C. glutamicum, which belongs to phylum Actinobacteria, is able to biosynthesize heme from a coproporphyrin-dependent pathway. As reported in Fig. 3, CP III accumulation was shown in metabolites produced in the CGPB02, CGPB04, and CGPB07 strains. However, none of the engineered strains constructed in this study produced PP IX despite increased mRNA expression levels of the hemN gene (encoding coproporphyrinogen III oxidase) (Supplementary Fig. S7). Furthermore, we confirmed that PP IX was produced when coproporphyrinogen III oxidase derived from E. coli with hemAM, hemL and dtxR genes was heterogeneously expressed in C. glutamicum (Supplementary Fig. S8). This observation suggests that C. glutamicum may not have a protoporphyrin-dependent pathway for heme biosynthesis, and therefore is suitable in terms of being a coproporphyrin-producing platform strain.

Even though the mRNA expression levels of the hemA, hemL, hemB, hemC, hemD, hemE and hemY genes for CP III production, as well as that of the hemH gene, were increased, heme production in the CGPB04 strain was slightly decreased, compared with the CGPB02 strain (Supplementary Figs S3, S7). Regarding this result, we speculate that the DtxR protein and heme competed for ferrous ion as a cofactor and required metal ions, respectively. Although the heme production from CP III was increased in the culture supplemented with iron sulfate of the CGPB07 strain, the bioconversion yield from CP III to heme was still low at 31.55 ± 3.39% (Fig. 3d). It is tempting to speculate that the final biosynthetic section from CP III to heme may be a major bottleneck for heme biosynthesis. Kwon et al. suggested that the limited transport of a metal ion into the cell and the low activity of the HemH protein in vivo may limit heme biosynthesis in the recombinant E. coli37. It has been recently reported that heme biosynthesis in the coproporphyrin-dependent pathway is performed by the HemQ protein which decarboxylates coproheme resulting in heme54–57. Hence, a mechanistic and enzymatic perspective of the coproporphyrin-dependent pathway in C. glutamicum is required for enhanced heme production. Nevertheless, our result regarding heme concentration in the CGPB07 strain showed the high-level production, corresponding to 29.57 ± 2.46 mg/l (Fig. 3d).

In summary, we demonstrated the possibility of C. glutamicum as a platform strain for the microbial production of Zn-porphyrin Zn-CP III as well as heme, and the titer of the porphyrins in the final engineered strain CGPB07 are the highest, reported to date in bacteria (Figs 3d, 6, Supplementary Fig. S3). These bio-based compounds can be used as a valuable material in various research related to solar cell photosensitizers, biological sensors as well as biomedical application such as antimicrobial, antitumor and anticancer photodynamic therapy1–15,58,59. In further study, large scale production of Zn-porphyrin in bacteria by microbial and metabolic engineering can be directly applied to solar cell technology and biomedical research. Indeed, Toriya et al. has directly applied Zn-CP III biosynthesized from wild type Streptomyces sp. used in their previous study to photodynamic therapy for antitumor effect in mice40,59. To enhance porphyrin biosynthesis and increase the diversity of types of porphyrins, further microbial engineering in C. glutamicum should be performed, including rational pathway engineering of the endogenous metabolism toward increased availability of an additional rate-limiting step, fine-tuning of enzyme engineering for improving target enzymes representing low activity, and the development of transport systems for efficient substrate supply.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and chemicals

Cell culture media used in this study was purchased from Daejung chemical Co. (Korea) and BD Bioscience (USA). Genomic DNA and plasmid DNA were prepared using Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, USA) and GeneAll® Exprep Plasmid Kit (GeneAll, Korea), respectively. Oligo synthesis and DNA sequencing were performed by Macrogen (Korea) and Cosmogenetech (Korea), respectively. Restriction enzymes, Taq DNA polymerase and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from New England Biolabs (USA), GeneAll (Korea) and Promega (USA), respectively. DNA fragments treated by either polymerase, ligase or restriction enzymes were purified by GeneAll® Expin™ Gel SV Kit (GeneAll, Korea). HPLC-grade chemicals such as acetonitrile and methanol were purchased from Duksan (Korea). 5-Aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), Uroporphyrin III dihydrochloride (Echelon Biosciences, USA), coproporphyrin III dihydrochloride (Santa Cruz biotechnology, USA), protoporphyrin IX (Sigma-Aldrich) and heme (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used as standard chemicals for the quantitative analysis. Zn-CP III was prepared by the modified method described by Anttila et al.24. For quantitative real time-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, Hybrid-R prep kit, M-MLV reverse transcriptase and HiPi Real-Time PCR 2x Master Mix (SYBR green) were purchased from GeneAll (Korea), Bioneer (Korea) and Elpisbio (Korea), respectively.

Strains and plasmids

All plasmids and bacterial strains constructed and used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli DH5α was chosen as the cloning host strain, and C. glutamicum ATCC 13826 was used in the construction of recombinant strains and experiments for porphyrin production in this study. S. typhimurium, E. coli and C. glutamicum strains were used to obtain hemA, hemL and dtxR genes from genomic DNA, respectively.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or construct | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F−, deoR, endA1, gyrA96, hsdR17(rk−mk+), recA1, relA1, supE44, thi-1, Δ(lacZYA- argF)U169, (Phi80lacZdelM15) | Invitrogena |

| BL21 (DE3) | F− ompT gal dcm lon hsdSB (rB− mB−) λ(DE3 [lacI lacUV5-T7 gene 1 ind1 sam7 nin5]) | Invitrogena |

| ECPB01 | E. coli BL21, pMT-tac::hemAML | This study |

| ECPB02 | E. coli BL21, pMT-tac::hemAMLdtxR | This study |

| ECPB03 | E. coli BL21, pEKEx2::hemAMLdtxR | This study |

| C. glutamicum | ||

| ATCC 13826 | l-Glutamate producing industrial strain | ATCCb |

| Control strain | C. glutamicum ATCC 13826, pMT-trc | This study |

| CGPB01 | C. glutamicum ATCC 13826, pMT-trc::hemAML | This study |

| CGPB02 | C. glutamicum ATCC 13826, pMT-tac::hemAML | This study |

| CGPB03 | C. glutamicum ATCC 13826, pMT-tac::dtxR | This study |

| CGPB04 | C. glutamicum ATCC 13826, pMT-tac::hemAMLdtxR | This study |

| CGPB05 | C. glutamicum ATCC 13826, pEKEx2::hemAML | This study |

| CGPB06 | C. glutamicum ATCC 13826, pEKEx2::dtxR | This study |

| CGPB07 | C. glutamicum ATCC 13826, pEKEx2::hemAMLdtxR | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMT-trc | C. glutamicum-E. coli shuttle vector, Ptrc, AmpR, KanR, pCG1 ori | Ramzi et al. (2015) |

| pMT-tac | C. glutamicum-E. coli shuttle vector, Ptac, AmpR, KanR, pCG1 ori | Joo et al. (2017) |

| pMT-trc::hemAML | pMT-trc carrying hemAM and hemL genes | Ramzi et al. (2015) |

| pMT-tac::dtxR | pMT-tac carrying dtxR gene | This study |

| pMT-tac::hemAML | pMT-tac carrying hemAM and hemL genes | This study |

| pMT-tac::hemAMLdtxR | pMT-tac carrying hemAM, hemL, and dtxR genes | This study |

| pEKEx2 | C. glutamicum-E. coli shuttle vector, Ptac, lacI, KanR, pBL1 ori | This study |

| pEKEx2::dtxR | pEKEx2 carrying dtxR gene | This study |

| pEKEx2::hemAML | pEKEx2 carrying hemAM and hemL genes | This study |

| pEKEx2::hemAMLdtxR | pEKEx2 carrying hemAM, hemL, and dtxR genes | This study |

aInvitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, California, USA. bAmerican Type and Culture Collection, Manassas, USA.

All oligonucleotides for the construction of recombinant vectors were listed in Supplementary Table S1. pMT-tac and pEKEx2 vectors were used as E. coli and C. glutamicum shuttle vectors and for the expression of target genes in C. glutamicum. To express hemAM and hemL genes under the control of the tac promoter, the hemAM and hemL gene operon was amplified with HemAM BamHI F and HemL NotI R primers using pMT-trc::hemAML vector as a template. The hemAM-hemL gene fragment was ligated into BamHI- NotI restriction sites of the pMT-tac vector by T4 DNA ligation, resulting in the pMT-tac::hemAML vector. For the construction of pMT-tac::hemAMLdtxR and pMT-tac::dtxR vectors, the dtxR gene was amplified with DtxR NotI F and DtxR NotI R primers using pMT-tac::hemAML and pMT-tac vectors as a template, respectively. To prevent self-ligation by one-cut restriction digestion, the digested sample was treated with Cloned Alkaline Phosphatase (Takara, Japan). The dtxR gene fragment was ligated into the NotI restriction sites of pMT-tac::hemAML and pMT-tac vectors, resulting in pMT-tac::hemAMLdtxR and pMT-tac::dtxR vectors. In the same manner, the pEKEx2::hemAL vector was constructed by means of restriction digestion and ligation into PstI-SalI sites of the pEKEx2 vector. The dtxR gene was also introduced into SalI-BamHI sites of pEKEx2 and pEKEx2::hemAML vectors, resulting in pEKEx2::dtxR and pEKEx2::hemAMLdtxR. Except for an adjacent gene from a promoter, a ribosomal binding site (AAGGAG) was inserted between downstream of the stop codon and upstream of the start codon in individual genes. Transformation of all recombinant vectors in E. coli and C. glutamicum was performed by the methods previously described27.

Culture medium and conditions

For the construction of engineered strains, E. coli and C. glutamicum were grown overnight in shaking cultivation at 37 °C and 30 °C, respectively, and 200 rpm in Luria–Bertani medium. C. glutamicum wild type and engineered strains were grown overnight in shaking cultivation at 30 °C and 150 rpm in brain–heart infusion (BHI) –. The seed culture for porphyrin production was washed once with modified CGXII medium and transferred to main flask cultivation at a starting OD600 of 1. Main flask cultivation for porphyrin production was conducted in 500 ml baffled flasks containing 100 ml modified CGXII medium containing 40 g/l glucose and 1 mM Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). For glutamate overproduction, 6 U/ml penicillin G was supplemented after 12 h of cultivation. Modified CGXII medium consists of 20 g (NH4)2SO4, 5 g urea, 1 g KH2PO4, 1 g K2HPO4, 42 g 3-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid (MOPS), 0.25 g MgSO4·7H2O, 10 mg CaCl2, 10 mg FeSO4·7H2O, 0.1 mg MnSO4·H2O, 1 mg ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.31 mg CuSO4·5H2O, 0.02 mg NiCl2·6H2O and 0.2 mg biotin per liter. Recombinant vectors in engineered strains were maintained by relevant concentrations of antibiotics (50 mg/l ampicillin and 25 mg/l kanamycin).

For fed-batch fermentation, stock cells were streaked onto BHI agar plates with 25 mg/l kanamycin and cultured for 30 h of standing incubation at 30 °C. One colony was used to inoculate 20 ml of the first seed culture and grown overnight in shaking cultivation at 30 °C and 150 rpm. The first seed culture was transferred to 200 ml of baffled flasks containing the second seed culture. The second seed culture was washed once with modified CGXII medium and transferred to fermenter containing 1.8 l modified CGXII medium, 40 g/l glucose, 1 mM IPTG and 25 mg/l kanamycin. The fermentation was performed at 30 °C and 300 to 600 rpm. The pH was automatically maintained at 6.8 by 4 M NaOH and 5 M H2SO4. Air aeration rate and dissolved oxygen were maintained at 1 vvm and 30% of air saturation, respectively. The foam was removed by the addition of 1:10 diluted antifoam Y-30 emulsion (Sigma-Aldrich). When glucose was lower than 20 g/l, 50% glucose stock solution was manually fed.

Analytical methods

Cell growth of all strains used in this study was measured at OD600 using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Mecasys Co., Ltd., Korea). The dry cell weight was experimentally determined on the basis of the correlation model OD600 1 = 0.282 g dry cell weight (DCW)/l and used for the calculation of biomass concentration of fed-batch fermentation. Glucose concentration was estimated using a Glucose (GO) Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). For measurement of intracellular metabolites, 1 ml of cell pellet was harvested by centrifugation (13,000 rpm at 4 °C for 3 minutes), and the supernatant excluding the cell pellet was used for the measurement of extracellular metabolites. For the extraction of the metabolite from cells, including inter alia, heme and other porphyrins, the cell pellet was disrupted using-modified actone:HCl extraction methods described by Espinas et al.60. After 1 ml of acetone:HCl (95:5) buffer was added to the cell-harvested tube, the mixture was vortexed and diluted with 1 ml of 1 M NaOH. The intracellular sample which was disrupted and supernatant was filtered using an MCE (Mixed Cellulose Ester) filter (Hyundai micro, Korea) for concentration analysis. Porphyrin concentration was determined using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Waters Corporation, USA), which consists of a dual λ absorbance detector (Waters 2487), binary HPLC pump (Waters 1525), and autosampler (Waters 2707). The filtered sample was separated in a SUPELCOSIL™ LC-18-DB HPLC Column 5 μm particle size, L × I.D. 250 × 4.6 mm (Supelco Inc., USA) using a linear gradient method of 20–95% solvent A in B at 40 °C. Solvent A is a 10:90 (v/v) HPLC grade methanol:acetonitrile mixture, and solvent B is a 0.5% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in HPLC grade water. The flow rate was 1 ml/min for 40 minutes, and the absorbance was determined at 400 nm. The data were estimated using Waters Empower-3 software. ALA concentration was measured using the colorimetric assay called Ehrlich’s reagent61. One volume of the supernatant was chemically reacted with 0.5 volume of 1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.8) and 0.25 volume of acetylacetone at 100 °C for 15 minutes. After that, the reagent mixture was cooled in an ice bath for 15 minutes. The modified Ehrlich’s reagent was added to the cooled mixture and stayed at room temperature for 30 minutes. The absorbance was determined at 554 nm using Epoch 2 microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, USA).

RNA Preparation and qRT-PCR

To prepare total RNA, the CGPB02 and CGPB04 strains were cultivated in modified CGXII medium and harvested at 12 h. Total RNA in the cell pellet was extracted using a Hybrid-R prep kit (GeneAll, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA with random primer was denatured at 65 °C for 10 minutes, and reverse-transcriptionally synthesized to cDNA templates by M-MLV reverse transcriptase. All oligonucleotides for qRT-PCR were designed based on target gene sequence (Supplementary Table S2). qRT-PCR analysis was determined using a StepOnePlus thermocycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with HiPi Real-Time PCR 2x Master Mix (SYBR green) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mRNA level of each gene of the CGPB04 strain was calculated relative to those of the CGPB02 strain using the comparative ΔΔCt method and was always normalized using the 16S rRNA level as an internal standard62.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(N.R.F.) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIP) (No. 2018R1A2B2003704). We would like to express gratitude to School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology for BK21 PLUS, Korea University for processing charges in Open Access journals.

Author Contributions

Y.J.K. and S.O.H. designed research. Y.J.K. performed research and wrote the manuscript. Y.C.J., J.E.H., S.W.K., C.P. and S.O.H. revised and edited the manuscript. Y.J.K., E.L., M.E.L. and J.S. performed fed-batch fermentation. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32854-9.

References

- 1.Auwarter W, Ecija D, Klappenberger F, Barth JV. Porphyrins at interfaces. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:105–120. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.den Boer D, et al. Detection of different oxidation states of individual manganese porphyrins during their reaction with oxygen at a solid/liquid interface. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:621–627. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew S, et al. Dye-sensitized solar cells with 13% efficiency achieved through the molecular engineering of porphyrin sensitizers. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:242–247. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yella A, et al. Porphyrin-sensitized solar cells with cobalt (II/III)-based redox electrolyte exceed 12 percent efficiency. Science. 2011;334:629–634. doi: 10.1126/science.1209688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryu WH, et al. Heme biomolecule as redox mediator and oxygen shuttle for efficient charging of lithium-oxygen batteries. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12925. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter KA, et al. Porphyrin-phospholipid liposomes permeabilized by near-infrared light. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3546. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou Q, et al. Biological Photothermal Nanodots Based on Self-Assembly of Peptide-Porphyrin Conjugates for Antitumor Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1921–1927. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ussia M, et al. Freestanding photocatalytic materials based on 3D graphene and polyporphyrins. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5001. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23345-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yella A, et al. Molecular engineering of push-pull porphyrin dyes for highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells: the role of benzene spacers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:2973–2977. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alibabaei L, et al. Application of Cu(II) and Zn(II) coproporphyrins as sensitizers for thin film dye sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010;3:956–961. doi: 10.1039/b926726c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Zhang Q, Liu JC, Li RZ, Jin NZ. A novel self-assembly with two acetohydrazide zinc porphyrins coordination polymer for supramolecular solar cells. Org. Electron. 2017;41:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.orgel.2016.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iritani K, Tahara K, Hirose K, De Feyter S, Tobe Y. Construction of cyclic arrays of Zn-porphyrin units and their guest binding at the solid-liquid interface. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 2016;52:14419–14422. doi: 10.1039/c6cc07121j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franke M, et al. Zinc Porphyrin Metal-Center Exchange at the Solid-Liquid Interface. Chemistry. 2016;22:8520–8524. doi: 10.1002/chem.201600634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Bai H, Xu JF, Wang S, Zhang X. Supramolecular Porphyrin Photosensitizers: Controllable Disguise and Photoinduced Activation of Antibacterial Behavior. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:13950–13957. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b02611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyeon JE, et al. Biomimetic magnetoelectric nanocrystals synthesized by polymerization of heme as advanced nanomaterials for biosensing application. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018;114:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvete, M. J. F. et al. A Cost-Efficient Method for Unsymmetrical Meso-Aryl Porphyrin Synthesis Using NaY Zeolite as an Inorganic Acid Catalyst. Molecules22, doi:10.3390/molecules22050741 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Henriques CA, et al. Ecofriendly Porphyrin Synthesis by using Water under Microwave Irradiation. ChemSusChem. 2014;7:2821–2824. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201402464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosca F, Tagliapietra S, Garino C, Cravotto G, Barge A. Extensive methodology screening of meso-tetrakys-(furan-2-yl)-porphyrin microwave-assisted synthesis. New J. Chem. 2016;40:2574–2581. doi: 10.1039/c5nj02888d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao EM, et al. Optogenetic regulation of engineered cellular metabolism for microbial chemical production. Nature. 2018;555:683-+. doi: 10.1038/nature26141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shomar H, et al. Metabolic engineering of a carbapenem antibiotic synthesis pathway in Escherichia coli. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018;14:794-+. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SY, et al. One-step fermentative production of poly(lactate-co-glycolate) from carbohydrates in Escherichia coli. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:435-+. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu TM, et al. Employing a biochemical protecting group for a sustainable indigo dyeing strategy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018;14:256-+. doi: 10.1038/Nchembio.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadish, K. M., Smith, K. M. & Guilard, R. The porphyrin handbook. (Academic Press, 2000).

- 24.Anttila J, et al. Is coproporphyrin III a copper-acquisition compound in Paracoccus denitrificans? Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2011;1807:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Layer G, Reichelt J, Jahn D, Heinz DW. Structure and function of enzymes in heme biosynthesis. Protein Sci. 2010;19:1137–1161. doi: 10.1002/pro.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Georgi T, Rittmann D, Wendisch VF. Lysine and glutamate production by Corynebacterium glutamicum on glucose, fructose and sucrose: roles of malic enzyme and fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Metab. Eng. 2005;7:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joo YC, Hyeon JE, Han SO. Metabolic Design of Corynebacterium glutamicum for Production of l-Cysteine with Consideration of Sulfur-Supplemented Animal Feed. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017;65:4698–4707. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joo, Y. C. et al. Bio-Based Production of Dimethyl Itaconate From Rice Wine Waste-Derived Itaconic Acid. Biotechnol. J. 12, 10.1002/biot.201700114 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kim SJ, Hyeon JE, Jeon SD, Choi GW, Han SO. Bi-functional cellulases complexes displayed on the cell surface of Corynebacterium glutamicum increase hydrolysis of lignocelluloses at elevated temperature. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2014;66:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park, S. H. et al. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for L-arginine production. Nat. Commun. 5, 10.1038/ncomms5618 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Jo S, et al. Modular pathway engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum to improve xylose utilization and succinate production. J. Biotechnol. 2017;258:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramzi AB, Hyeon JE, Kim SW, Park C, Han SO. 5-Aminolevulinic acid production in engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum via C5 biosynthesis pathway. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2015;81:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramzi AB, Hyeon JE, Han SO. Improved catalytic activities of a dye-decolorizing peroxidase (DyP) by overexpression of ALA and heme biosynthesis genes in Escherichia coli. Process Biochem. 2015;50:1272–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2015.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noh MH, Lim HG, Park S, Seo SW, Jung GY. Precise flux redistribution to glyoxylate cycle for 5-aminolevulinic acid production in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2017;43:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng L, et al. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for efficient production of 5-aminolevulinic acid. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016;113:1284–1293. doi: 10.1002/bit.25886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Kang Z, Chen J, Du G. Optimization of the heme biosynthesis pathway for the production of 5-aminolevulinic acid in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8584. doi: 10.1038/srep08584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon SJ, de Boer AL, Petri R, Schmidt-Dannert C. High-level production of porphyrins in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli: Systematic extension of a pathway assembled from overexpressed genes involved in heme biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:4875–4883. doi: 10.1128/Aem.69.8.4875-4883.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen MT, et al. Assembly of highly standardized gene fragments for high-level production of porphyrins in E. coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 2015;4:274–282. doi: 10.1021/sb500055u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi SI, Park J, Kim P. Heme Derived from Corynebacterium glutamicum: A Potential Iron Additive for Swine and an Electron Carrier Additive for Lactic Acid Bacterial Culture. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017;27:500–506. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1611.11010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toriya M, et al. Zincphyrin, a novel coproporphyrin III with zinc from Streptomyces sp. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1993;46:196–200. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Elliott M, Elliott T. Conditional stability of the HemA protein (glutamyl-tRNA reductase) regulates heme biosynthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:1211–1219. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1211-1219.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L, Wilson S, Elliott T. A mutant HemA protein with positive charge close to the N terminus is stabilized against heme-regulated proteolysis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:6033–6041. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6033-6041.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frunzke J, Gatgens C, Brocker M, Bott M. Control of Heme Homeostasis in Corynebacterium glutamicum by the Two-Component System HrrSA. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:1212–1221. doi: 10.1128/Jb.01130-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu X, Jin H, Cheng X, Wang Q, Qi Q. Transcriptomic analysis for elucidating the physiological effects of 5-aminolevulinic acid accumulation on Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microbiol. Res. 2016;192:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wennerhold J, Bott M. The DtxR regulon of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:2907–2918. doi: 10.1128/Jb.188.8.2907-2918.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brune, I. et al. The DtxR protein acting as dual transcriptional regulator directs a global regulatory network involved in iron metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum. BMC Genomics7, 10.1186/1471-2164-7-21 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Bott M, Brocker M. Two-component signal transduction in Corynebacterium glutamicum and other corynebacteria: on the way towards stimuli and targets. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;94:1131–1150. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4060-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santamaria R, Gil JA, Mesas JM, Martin JF. Characterization of an Endogenous Plasmid and Development of Cloning Vectors and a Transformation System in. Brevibacterium-Lactofermentum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1984;130:2237–2246. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamamoto S, Suda M, Niimi S, Inui M, Yukawa H. Strain Optimization for Efficient Isobutanol Production Using Corynebacterium glutamicum Under Oxygen Deprivation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013;110:2938–2948. doi: 10.1002/bit.24961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bentley WE, Mirjalili N, Andersen DC, Davis RH, Kompala DS. Plasmid-encoded protein: the principal factor in the “metabolic burden” associated with recombinant bacteria. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1990;35:668–681. doi: 10.1002/bit.260350704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramirez EA, Velazquez D, Lara AR. Enhanced plasmid DNA production by enzyme-controlled glucose release and an engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016;38:651–657. doi: 10.1007/s10529-015-2017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Labbe RF, Vreman HJ, Stevenson DK. Zinc protoporphyrin: A metabolite with a mission. Clin. Chem. (Washington, DC, U. S.) 1999;45:2060–2072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibson KD, Neuberger A, Tait GH. Studies on the biosynthesis of porphyrin and bacteriochlorophyll by Rhodopseudomonas spheroides. 1. The effect of growth conditions. Biochem. J. 1962;83:539–549. doi: 10.1042/bj0830539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dailey HA, Gerdes S, Dailey TA, Burch JS, Phillips JD. Noncanonical coproporphyrin-dependent bacterial heme biosynthesis pathway that does not use protoporphyrin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:2210–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416285112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dailey TA, et al. Discovery and Characterization of HemQ An Essential Heme Biosynthetic Pathway Component. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:25978–25986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dailey HA, Gerdes S. HemQ: An iron-coproporphyrin oxidative decarboxylase for protoheme synthesis in Firmicutes and Actinobacteria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015;574:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Celis AI. A Structure-Based Mechanism for Oxidative Decarboxylation Reactions Mediated by Amino Acids and Heme Propionates in Coproheme Decarboxylase (HemQ) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1900–1911. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alenezi K, Tovmasyan A, Batinic-Haberle I, Benov LT. Optimizing Zn porphyrin-based photosensitizers for efficient antibacterial photodynamic therapy. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2017;17:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toriya M, Yamamoto M, Saeki K, Fujii Y, Matsumoto K. Antitumor effect of photodynamic therapy with zincphyrin, zinc-coproporphyrin III, in mice. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 2001;65:363–370. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Espinas NA, Kobayashi K, Takahashi S, Mochizuki N, Masuda T. Evaluation of Unbound Free Heme in Plant Cells by Differential Acetone Extraction. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:1344–1354. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mauzerall D, Granick S. The occurrence and determination of delta-amino-levulinic acid and porphobilinogen in urine. J. Biol. Chem. 1956;219:435–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) Methods (Amsterdam, Neth.) 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.