Abstract

Mercury (Hg) is a contaminant of major concern in Arctic marine ecosystems. Decades of Hg observations in marine biota from across the Canadian Arctic show generally higher concentrations in the west than in the east. Various hypotheses have attributed this longitudinal biotic Hg gradient to regional differences in atmospheric or terrestrial inputs of inorganic Hg, but it is methylmercury (MeHg) that accumulates and biomagnifies in marine biota. Here, we present high-resolution vertical profiles of total Hg and MeHg in seawater along a transect from the Canada Basin, across the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (CAA) and Baffin Bay, and into the Labrador Sea. Total Hg concentrations are lower in the western Arctic, opposing the biotic Hg distributions. In contrast, MeHg exhibits a distinctive subsurface maximum at shallow depths of 100–300 m, with its peak concentration decreasing eastwards. As this subsurface MeHg maximum lies within the habitat of zooplankton and other lower trophic-level biota, biological uptake of subsurface MeHg and subsequent biomagnification readily explains the biotic Hg concentration gradient. Understanding the risk of MeHg to the Arctic marine ecosystem and Indigenous Peoples will thus require an elucidation of the processes that generate and maintain this subsurface MeHg maximum.

Introduction

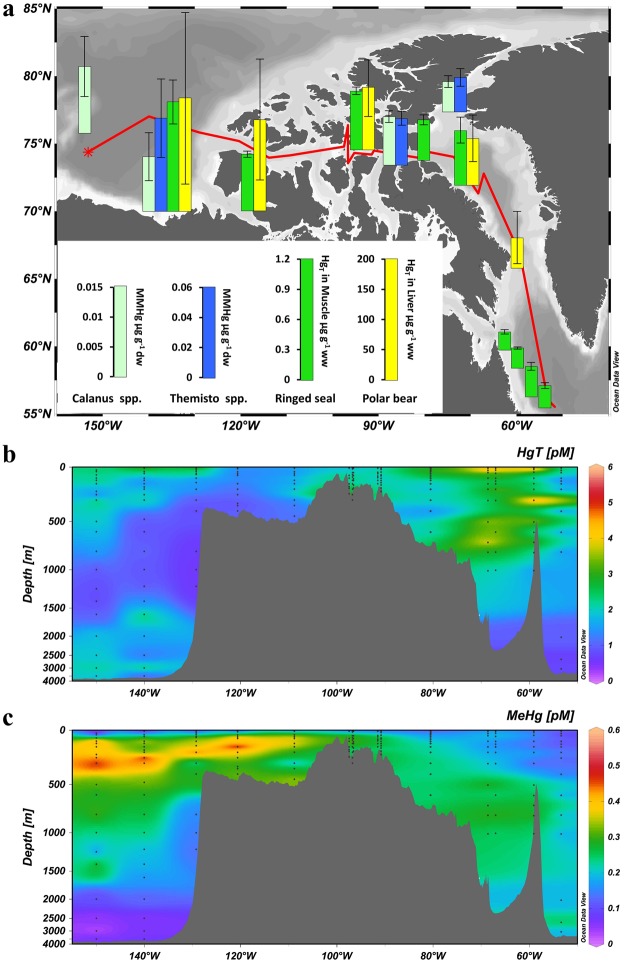

Monitoring data collected during the past four decades have shown Hg concentrations in Canadian Arctic marine mammals (e.g., beluga whales, ringed seals, polar bears) to be highly elevated, frequently exceeding toxicity thresholds1,2. This has raised major concerns over the health of marine mammals and Indigenous Peoples whose traditional diets include marine mammal tissues. Mercury concentrations in marine biota are generally higher in the Beaufort Sea and western Canadian Arctic Archipelago (CAA) than in the eastern CAA and Baffin Bay1–3. This longitudinal gradient is not limited to apex predators4,5, but extends to organisms at lower trophic levels such as zooplankton (e.g., Themisto spp., Calanus spp.)6 (Fig. 1a). Whereas regional variations in top predator Hg concentrations may be linked to feeding behavior and dietary preference5, observed spatial patterns persist after adjustments are made to account for trophic position3.

Figure 1.

Mercury concentrations in the marine food web and seawater across the Canadian Arctic and Labrador Sea. (a) Map showing Hg concentrations in the marine food web, and seawater sampling sites; (b) distribution of total Hg (HgT); and (c) methylmercury (MeHg) in seawater along a longitudinal (west-to-east) section. The bar charts in (a) show mean concentrations ± one standard deviation of monomethylmercury (MMHg) in Calanus spp. and Themisto spp. collected from 1998 to 20126, total Hg (HgT) in muscle of adult ringed seals collected in 2007 and 20113,5, and HgT in liver of polar bears collected from 2005 to 20083. The base map with bathymetry was created using Ocean Data View (version 4.0)40.

Extensive efforts have been made to identify factors that control the spatial trends in marine biota and to develop appropriate mitigation strategies to reduce biotic Hg concentrations. Most hypotheses attribute higher marine biotic Hg concentrations in the western Canadian Arctic to elevated inputs of inorganic Hg to these regions. These inputs include (1) atmospheric deposition of anthropogenic Hg from Asian sources3, which is enhanced locally by atmospheric mercury depletion events (AMDEs) during polar sunrise7; (2) riverine Hg input from the Mackenzie River8,9, which may be enhanced by tundra uptake of atmospheric elemental Hg10 [and permafrost thawing11; and (3) a naturally high geological background of Hg12. These inorganic Hg-based hypotheses do not account for the fact that it is methylmercury (MeHg), not inorganic Hg, that accumulates and biomagnifies in marine biota2. The discovery of a subsurface MeHg enrichment in global oceans13–16 suggests that seawater MeHg may play a more important role in determining marine biotic Hg concentrations17,18, especially in regions such as the Beaufort Sea15 and the central Arctic Ocean16 where the maximum MeHg concentration was observed at shallow depths.

During the 2015 Canadian Arctic GEOTRACES cruises (July 14–September 16, 2015) aboard the Canadian Research Icebreaker CCGS Amundsen, we measured high-resolution vertical profiles of total mercury (HgT) (Fig. 1b) in unfiltered seawater, along a 5200-km transect (150°–53° W) from the Canada Basin in the west, through CAA to Baffin Bay in the east, reaching the Labrador Sea in the North Atlantic Ocean (Figs 1a, S1). Total Hg concentrations show a distinctive longitudinal gradient along the transect (Fig. 1b, Table 1), with concentrations increasing from the Canada Basin and the western CAA (1.76 ± 1.15 pM) to the eastern CAA and Baffin Bay (2.62 ± 1.97 pM). These results are comparable to the limited HgT dataset reported for Canadian Arctic waters15,19,20. The lowest concentrations were found in the Labrador Sea (0.65 ± 0.18 pM), slightly higher than those (0.44 ± 0.10 pM, 0.25–0.67 pM) measured in June 2014 in a similar area21.

Table 1.

Concentrations of total Hg (HgT) and methylmercury (MeHg) in seawater from the Canadian Arctic and Labrador Sea.

| Regions | Stations | Depth | HgT (pM) | MeHg (pM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada Basin, Beaufort Sea, and Western CAA | CB1–4; CAA6–9 | 0–500 m | 1.90 ± 1.25, 0.73–8.55, n = 77 | 0.30 ± 0.14, 0.02–0.56, n = 77 |

| Full depth | 1.76 ± 1.15, 0.55–8.55, n = 101 | 0.27 ± 0.14, 0.02–0.56, n = 100 | ||

| Eastern CAA and Baffin Bay | CAA1–5; BB1–3 | 0–500 m | 2.60 ± 2.06, 0.80–12.35, n = 78 | 0.19 ± 0.08, 0.04–0.44, n = 78 |

| Full depth | 2.62 ± 1.97, 0.80–12.35, n = 93 | 0.20 ± 0.09, 0.04–0.44, n = 93 | ||

| Labrador Sea | K1 | 0–500 m | 0.62 ± 0.19, 0.30–0.92, n = 9 | 0.09 ± 0.04, 0.03–0.12, n = 9 |

| Full depth | 0.65 ± 0.18, 0.30–0.95, n = 14 | 0.12 ± 0.06, 0.03–0.24, n = 15 |

The low seawater HgT concentrations in the Canada Basin, to the west, contrast with expectations based on the hypothesized elevated atmospheric and riverine inputs of Hg into this region. Whereas AMDEs do result in high springtime deposition, the low Canada Basin HgT concentrations are consistent with findings that most AMDEs occur in coastal regions and most of the deposited Hg is re-emitted to the atmosphere before snow melts22, thus limiting its transfer into the ocean. Likewise, Hg transported by rivers, possibly enhanced by tundra uptake, permafrost thawing, or geological enrichment, is likely deposited with sediment in coastal areas23 or escapes rapidly from the river plume to the atmosphere9. Furthermore, because MeHg accounts for <1% of the HgT in the Mackenzie River water8,23, and the atmospheric input of Hg is predominantly inorganic22,24,25, the Hg delivered to Canada Basin waters requires transformation to MeHg, the biomagnifying Hg species, to account for observed higher biotic Hg concentrations. Therefore, elevated input of inorganic Hg in the western relative to the eastern Arctic does not provide, by itself, a plausible mechanism to explain higher biotic Hg concentrations in the western Canadian Arctic (Fig. 1b).

Concentrations of MeHg (0.23 ± 0.12 pM, 0.02 to 0.56 pM), measured during the 2015 Canadian Arctic GEOTRACES cruises (Fig. 1c), are comparable to values reported in previous studies15,19,20 and show an overall decoupling from HgT distributions in the water column (Fig. 1c). The improved sampling resolution reveals distinctive vertical and longitudinal variations along the transect. Vertically, MeHg concentrations are lowest at the surface, increase with depth to a subsurface maximum, and subsequently decrease towards the bottom. Longitudinally, the subsurface MeHg peak value is highest (~0.5 pM) in the western part of the section and decreases to ~0.2 pM over the Barrow Strait sill into the eastern CAA, eventually dropping to ~0.1 pM in the Labrador Sea (Fig. 1c, Table 1). The depth of the subsurface MeHg maximum varies from west to east: MeHg peaks at depths of ~300 m at the westernmost station in the Canada Basin and shoals progressively eastward to ~100 m in the western CAA. Farther east, the subsurface MeHg peak remains at ~100 m in the eastern CAA and Baffin Bay, but deepens to ~200 m in the Labrador Sea.

Regional differences in polar bear hair Hg concentrations between the Beaufort Sea and Hudson Bay were tentatively attributed to regional differences in seawater MeHg concentrations that resulted in different degrees of bioaccumulation18, but high-resolution (vertical and horizontal) water-column MeHg concentration data were not available at that time to support this hypothesis. The distribution of the subsurface MeHg peak along our transect directly links the spatial distribution of aqueous MeHg concentrations to biotic uptake (Fig. 1a,c).

Enrichment of MeHg in the subsurface water column (300–1000 m) is a common feature of many ocean basins13,14. A notable difference is that the subsurface MeHg peak occurs at a much shallower depth in the western Canadian Arctic (100–300 m), in agreement with recent reports from the Beaufort Sea15 and the central Arctic Ocean16. This MeHg maximum occurs at shallow depths that are just below the surface productive layer (see Fig. S2), which may enhance MeHg availability to organisms at the base of the marine food webs16. Phytoplankton are known to bioconcentrate MeHg from seawater26, and zooplankton bioaccumulate it directly from seawater and by trophic transfer through their diet27,28; as a result, higher phytoplankton and zooplankton MeHg concentrations have been linked to higher seawater MeHg concentrations29. Among the three most important herbivores in Arctic waters, Calanus hyperboreus and C. finmarchicus are concentrated in shallow water (<300 m) except during winter, whereas C. glacialis spend all life stages in the top 300 m30,31. The amphipod consumers of these Calanus species, Themisto spp., also inhabit shallow waters32, as does Arctic cod (Boreogadus saida,<500 m), key species in the Arctic marine food web33. Given that the MeHg-enriched waters lie within the main habitat of low trophic level marine biota in these waters, spatial variations in MeHg concentrations within the subsurface zone can readily explain the higher biotic Hg concentrations in the western compared to the eastern regions of the section.

Therefore, to understand what controls Arctic biotic Hg distributions and predict future conditions, characterization of atmospheric and terrestrial sources of inorganic Hg inputs to the Arctic Ocean is not sufficient. Detailed investigations will be required to identify processes controlling the production and loss of MeHg associated with the upper halocline waters of the western Arctic Ocean and how these processes respond to the changing climate. The subsurface seawater MeHg maximum in the oceans is typically attributed to in situ MeHg production associated with organic matter remineralization13–16. In the central Arctic Ocean, Heimbürger et al.16 suggested that sinking particles are slowed down at the shallow pycnocline where they undergo remineralization and stimulate in situ MeHg production. It remains unclear what microbial or abiotic processes are responsible for Hg methylation at such shallow depths where dissolved oxygen is well above 75% of the saturation value (Fig. S2). Alternatively, the MeHg maximum in the upper halocline in the western Canadian Arctic could be supported by isopycnal transport, along with the metabolite-enriched upper halocline waters, from sediments of the productive Chukchi and Beaufort Shelves34. Understanding the risk of MeHg to the Arctic marine ecosystem and Indigenous Peoples will thus require an elucidation of the processes that generate and maintain the subsurface seawater MeHg maximum.

Methods

Seawater sampling and analyses were carried out following ultraclean techniques recommended for the GEOTRACES program35,36. Seawater was collected onboard the Canadian Research Icebreaker CCGS Amundsen in pre-cleaned, 12-L Teflon-coated Go-Flo bottles mounted on a Trace Metal-Clean Rosette System. Following rosette retrieval, the Go-Flo bottles were promptly moved to a clean laboratory van where seawater for HgT and MeHg analyses was collected into pre-cleaned, 250-mL amber glass bottles37. Immediately after collection, the seawater samples were acidified with 0.5% (v:v) ultraclean acid (CMOS grade JT Baker HCl for HgT, and trace metal clean grade Fisher Scientific H2SO4 for MeHg) and stored at 4 °C until analysis. The acidification breaks down dimethylmercury (DMHg) to monomethylmercury (MMHg)38 and, thus, the MeHg reported herein represents the sum of MMHg and DMHg.

Within 48 hr of sampling, HgT was analyzed in the Portable In-situ Laboratory for Mercury Speciation (PILMS) onboard the icebreaker (http://www.amundsen.ulaval.ca/capacity/portable-insitu-lab-mercury-speciation.php). The analysis was carried out on a Tekran 2600 Hg analyzer following U.S EPA Method 1631, which involves BrCl oxidation, SnCl2 reduction, gold trap pre-concentration and measurement by cold vapor atomic fluorescence spectrometry (CVAFS). Water samples were analyzed for MeHg at the PILMS or at the Ultra-Clean Trace Elements Laboratory (UCTEL) at the University of Manitoba. Concentrations of MeHg were measured on an automated MeHg analyzer (MERX-M, Brooks Rand) following an adapted ascorbic acid-assisted direct ethylation method39, which involves ethylation, Tenax trap pre-concentration, gas chromatographic separation and CVAFS quantification. The original method39 was modified for use with ~40-mL sample volumes using acetate buffers to adjust pH. Daily calibration curves were prepared by adding standards solutions to filtered seawater to improve recovery from the seawater matrix. The detection limit (DL) was estimated at 0.25 pM and 0.014 pM for HgT and MeHg, respectively, as three times the standard deviation of seven laboratory blank replicates. Whenever seawater was sampled, Milli-Q water was collected in pre-cleaned 250-mL amber glass bottles to serve as field blanks, the concentrations of which were always lower than the DL for both HgT and MeHg. Certified reference seawater BCR579 (9.5 ± 2.5 pmol kg−1 or 9.7 ± 2.5 pM when corrected for density, Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements, European Commission - Joint Research Centre) was analyzed for HgT and the recovery was 93–116%. Since no certified reference seawater is available for MeHg, a 0.01 pmol MMHg spike was used during sample analysis and its recovery was 87–114%.

Seawater fluorescence was measured in real-time with a chlorophyll fluorometer (Seapoint) installed on the rosette. To calibrate the fluorometer output, discrete seawater samples were measured for chlorophyll-α fluorescence concentrations.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada, ArcticNet, the Canadian Arctic GEOTRACES program, and the Canada Research Chairs Program. We thank W. Xu, A. Elliott, J. Li, M. Colombo, P. Chandan, J. Cullen, Z. Gao, D. Janssen, D. Semienuk, K. Orians, K. Purdon, S. L. Jackson, and R. Fox for rosette sample collection; R. François, J. Cullen, P. Tortell, K. Orians, and K. Brown for organizing the sampling activities; D. Armstrong, M. Soon, and K. Levesque for assistance with logistics; as well as the captains and crew of the Canadian Research Icebreaker CCGS Amundsen. We are grateful to R. Letcher for providing a digital version of polar bear Hg data.

Author Contributions

F.W. and K.W. initiated and designed this project, F.W., K.W. and K.M.M. designed the sampling plan. K.W. and K.M.M. collected and analyzed samples. K.W., F.W., K.M.M., R.W.M., A.B.-L. and A.M. interpreted data. K.W. and F.W. led the writing of the manuscript with major contributions and support from K.M.M., R.W.M. and A.M.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32760-0.

References

- 1.Dietz R, et al. What are the toxicological effects of mercury in Arctic biota? Science of the Total Environment. 2013;443:775–790. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AMAP. AMAP Assessment 2011: Mercury in the Arctic. 193 (Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program, Oslo, Norway, 2011).

- 3.Brown TM, Macdonald RW, Muir DC, Letcher RJ. The distribution and trends of persistent organic pollutants and mercury in marine mammals from Canada’s Eastern Arctic. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;618:500–517. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Routti H, et al. Spatial and temporal trends of selected trace elements in liver tissue from polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from Alaska, Canada and Greenland. J. Environ. Monitor. 2011;13:2260–2267. doi: 10.1039/c1em10088b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown TM, et al. Mercury and cadmium in ringed seals in the Canadian Arctic: Influence of location and diet. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;545:503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pomerleau C, et al. Pan-Arctic concentrations of mercury and stable isotope ratios of carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) in marine zooplankton. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;551:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroeder W, et al. Arctic springtime depletion of mercury. Nature. 1998;394:331–332. doi: 10.1038/28530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leitch DR, et al. The delivery of mercury to the Beaufort Sea of the Arctic Ocean by the Mackenzie River. Sci. Total Environ. 2007;373:178–195. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher JA, et al. Riverine source of Arctic Ocean mercury inferred from atmospheric observations. Nature Geosci. 2012;5:499–504. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obrist D, et al. Tundra uptake of atmospheric elemental mercury drives Arctic mercury pollution. Nature. 2017;547:201–204. doi: 10.1038/nature22997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuster, P. F. et al. Permafrost stores a globally significant amount of mercury. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 10.1002/2017GL075571 (2018).

- 12.Wagemann R, Innes S, Richard P. Overview and regional and temporal differences of heavy metals in Arctic whales and ringed seals in the Canadian Arctic. Sci. Total Environ. 1996;186:41–66. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(96)05085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sunderland EM, Krabbenhoft DP, Moreau JW, Strode SA, Landing WM. Mercury sources, distribution, and bioavailability in the North Pacific Ocean: Insights from data and models. Global Biogeochem. Cycles. 2009;23:GB2010. doi: 10.1029/2008GB003425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cossa D, et al. Mercury in the Southern Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2011;75:4037–4052. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang F, Macdonald R, Armstrong D, Stern G. Total and methylated mercury in the Beaufort Sea: The role of local and recent organic remineralization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:11821–11828. doi: 10.1021/es302882d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heimbürger, L.-E. et al. Shallow methylmercury production in the marginal sea ice zone of the central Arctic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 5, 10.1038/srep10318 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cossa D, et al. Influences of bioavailability, trophic position, and growth on methylmercury in Hakes (Merluccius merluccius) from Northwestern Mediterranean and Northeastern Atlantic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:4885–4893. doi: 10.1021/es204269w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St. Louis VL, et al. Differences in mercury bioaccumulation between polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from the Canadian high-and sub-Arctic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:5922–5928. doi: 10.1021/es2000672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirk JL, et al. Methylated mercury species in marine waters of the Canadian high and sub Arctic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:8367–8373. doi: 10.1021/es801635m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehnherr I, Louis VLS, Hintelmann H, Kirk JL. Methylation of inorganic mercury in polar marine waters. Nature Geosci. 2011;4:298–302. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cossa D, et al. Sources, cycling and transfer of mercury in the Labrador Sea (Geotraces-Geovide cruise) Mar. Chem. 2017;198:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2017.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson KP, Blum JD, Keeler GJ, Douglas TA. Investigation of the deposition and emission of mercury in arctic snow during an atmospheric mercury depletion event. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008;113:D17304. doi: 10.1029/2008JD009893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graydon JA, Emmerton CA, Lesack LF, Kelly EN. Mercury in the Mackenzie River delta and estuary: Concentrations and fluxes during open-water conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2009;407:2980–2988. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baya PA, et al. Determination of monomethylmercury and dimethylmercury in the Arctic marine boundary layer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:223–232. doi: 10.1021/es502601z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soerensen AL, et al. A mass budget for mercury and methylmercury in the Arctic Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles. 2016;30:560–575. doi: 10.1002/2015GB005280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mason RP, Reinfelder JR, Morel FM. Uptake, toxicity, and trophic transfer of mercury in a coastal diatom. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996;30:1835–1845. doi: 10.1021/es950373d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CS, Fisher NS. Bioaccumulation of methylmercury in a marine copepod. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017;36:1287–1293. doi: 10.1002/etc.3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pućko M, et al. Transformation of mercury at the bottom of the Arctic food web: An overlooked puzzle in the mercury exposure narrative. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:7280–7288. doi: 10.1021/es404851b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schartup AT, et al. A Model for Methylmercury Uptake and Trophic Transfer by Marine Plankton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;52:654–662. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b03821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darnis, G. & Fortier, L. Zooplankton respiration and the export of carbon at depth in the Amundsen Gulf (Arctic Ocean). J. Geophys. Res. Oceans117, 10.1029/2011JC007374 (2012).

- 31.Falk-Petersen S, Mayzaud P, Kattner G, Sargent JR. Lipids and life strategy of Arctic Calanus. Mar. Biol. Res. 2009;5:18–39. doi: 10.1080/17451000802512267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalpadado P, Borkner N, Bogstad B, Mehl S. Distribution of Themisto (Amphipoda) spp. In the Barents Sea and predator-prey interactions. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2001;58:876–895. doi: 10.1006/jmsc.2001.1078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Majewski AR, et al. Distribution and diet of demersal Arctic Cod, Boreogadus saida, in relation to habitat characteristics in the Canadian Beaufort Sea. Polar Biol. 2016;39:1087–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00300-015-1857-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson LG, et al. Source and formation of the upper halocline of the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2013;118:410–421. doi: 10.1029/2012JC008291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamborg CH, Hammerschmidt CR, Gill GA, Mason RP, Gichuki S. An intercomparison of procedures for the determination of total mercury in seawater and recommendations regarding mercury speciation during GEOTRACES cruises. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 2012;10:90–100. doi: 10.4319/lom.2012.10.90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cutter GA, Bruland KW. Rapid and noncontaminating sampling system for trace elements in global ocean surveys. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 2012;10:425–436. doi: 10.4319/lom.2012.10.425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hammerschmidt CR, Bowman KL, Tabatchnick MD, Lamborg CH. Storage bottle material and cleaning for determination of total mercury in seawater. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 2011;9:426–431. doi: 10.4319/lom.2011.9.426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Black FJ, Conaway CH, Flegal AR. Stability of dimethyl mercury in seawater and its conversion to monomethyl mercury. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:4056–4062. doi: 10.1021/es9001218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munson KM, Babi B, Lamborg CH. Determination of monomethylmercury from seawater with ascorbic acid-assisted direct ethylation. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 2014;12:1–9. doi: 10.4319/lom.2014.12.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlitzer, R. Ocean Data View. odv.awi.de (2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.