Abstract

There is competing evidence that plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC), the most potent source of IFN-I, may initiate psoriasis. We targeted pDC function using the slc15a4feeble loss-of-function mouse whose pDC are unresponsive to TLR agonists. slc15a4feeble treated with the topical TLR7-agonist imiquimod (IMQ) demonstrated decreased epidermal thickening 24 hours post-treatment which was more pronounced by day 5 as compared to wildtype mice. These findings were specific to the acute IMQ model and not the protracted IL23 model that drives inflammation downstream of TLR activation. Systemically, slc15a4 was required for IMQ-induced weight loss and cutaneous accumulation of CD4+ and Siglec H+, but not CD11b+ cells. Consistent with this phenotype and the function of slc15a4, induction of IFN-I was virtually absent systemically and via cutaneous gene expression. Induction of other inflammatory cytokines (cytokine storm) was modestly blunted in slc15a4feeble except for inflammasome-associated genes consistent with slc15a4 being required for TLR7-mediated (but not inflammasome-mediated) inflammation downstream of IMQ. Surprisingly, only IFN-I gene expression was suppressed within IMQ-treated skin. Other genes including conserved psoriasiform trademark gene expression were augmented in slc15a4feeble versus littermate controls. Taken together, we have identified a role for slc15a4 but not canonical psoriasiform genes in the imiquimod model of psoriasiform dermatitis.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic autoimmune disease affecting approximately 2% of the population1. While the cause of psoriasis is unknown, there is competing evidence that plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) may be central to disease development2–5. pDCs are responsible for producing ~1000 times more type I interferon (IFN-I) than any other cell type. Thus, despite comprising only ~1% of the already rare dendritic cell population, pDCs account for approximately 50% of all circulating IFN-I following infection6. It has been proposed that pDCs in genetically predisposed individuals under certain environmental conditions and through their secretion of IFN-I, activate autoimmune T cells, in turn, eliciting a psoriasiform phenotype4.

Slc15a4

Solute carrier gene family 15 member 4 (SLC15A4) is a twelve membrane spanning protein also known as peptide/histidine transporter 1 (PHT1). Slc15a4 cellular gene expression essentially mirrors TLR7 and 9 expression being most highly expressed in antigen presenting cells, specifically plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) and B cells7–9. Consistently, a functional role for slc15a4 has only been demonstrated in these two cell types to date. Slc15a4 contains an acidic dileucine motif which likely mediates localization to the endosomal compartment via AP-37. Subsequent biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles (LROs) harboring TLR7 and TLR9 is defective without slc15a4. Thus TLR7 and TLR9 sensing is specifically lost in slc15a4 mutant mice resulting in acute loss of IFN-I production secondary to defective pDC within 6 hours post CpG injection7 and loss of B cell functional responses reported as early as 48 hours after TLR7 and TLR9 stimulation10.

slc15a4 phenotypes in vivo: SLE, acute and chronic viral infection

Consistent with the specific function and expression of slc15a4, slc15a4feeble loss of function mice are protected in the NZB and Fas(lpr) mouse models of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)11. GWAS studies have likewise identified slc15a4 as a genetic locus contributing to human lupus in 6 independent studies12–17.

The physiological role of slc15a4 is likely for protection against pathogens via TLR7/9 sensing. We tested this hypothesis and found that slc15a4 was not required for control of acute viremia but was necessary for virus-specific T cell activation and chronic viral clearance18. Here we extend our analysis of slc15a4 to examine its role in psoriasiform dermatitis mediated by the canonical TLR7 agonist imiquimod as compared to intradermal IL23 injection.

Imiquimod (IMQ) model, TLR7, IFN-I and plasmacytoid DC (pDC)

The IMQ model of acute skin inflammation has become the most widely used mouse model in this category over the past several years19. TLR7 sensing via pDC is thought to drive massive IFN-I expression within 6 hours that contributes to the induction of multiple inflammatory markers and histologic alterations in the skin seen within 12–24 hours19. However, there is also a vehicle-specific TLR7-independent effect which activates the inflammasome and contributes in part to the acanthosis and inflammation present in skin20,21. pDC production of IFN-I is an expected dramatic component of the IMQ model and critical to initiate psoriasis in a xenograft model4. However, deficiency of the IFN-I receptor was reported to have no effect in two IMQ studies5,20, while two subsequent IMQ studies demonstrated a significant role for the IFN-I receptor (IFNAR1)22,23. Similarly, pDC which are responsible for ~50% of all acute IFN-I24 has been implicated in psoriasis4 and the IMQ psoriasiform model. Yet surprisingly, targeting these cells did not result in any significant changes in the IMQ model5.

Here, we evaluated the role of slc15a4 in imiquimod-induced psoriasiform dermatitis. The mouse mutation examined in our study (feeble) has a one base-pair mutation in slc15a4 rendering the transporter inactive but feeble mice are otherwise genetically identical to their C57BL/6 J wildtype littermates (WT). Consistently, these mice are indistinguishable from WT during development, including DC and B cell phenotypic populations. However, there is a dramatic loss of DC function in response to TLR stimulation, especially regarding IFN-I secretion7,10 as well as a defect in IgG2c class switch recombination during CpG-adjuvanted vaccination10. Using this feeble model, we found significant decreases in disease initiation and progression in slc15a4feeble as compared to WT mice both locally and systemically.

Results

The role of pDC and IFN-I in the IMQ psoriasiform dermatitis model is controversial in addition to the source of IFN-I production4,5,20,22,23. Therefore, we examined an alternative target which may also be inhibited therapeutically to treat TLR-pDC driven immune pathology, slc15a4. Slc15a4 is required for pDC TLR7/9 sensing and subsequent TLR driven IFN-I production7. We and others found that slc15a4 was important in disease models8,11,18,25. Therefore, we hypothesized that studying slc15a4 deficiency in the IMQ psoriasiform dermatitis model may clarify the role of the TLR7-pDC-IFN-I pathway of immune pathology. A significant role would also justify slc15a4 as a specific therapeutic target to alleviate disease.

slc15a4 feeble mice are more resistant to imiquimod induced weight loss than epidermal skin thickening in an acute psoriasiform dermatitis model, but not resistant to IL23 induced skin inflammation

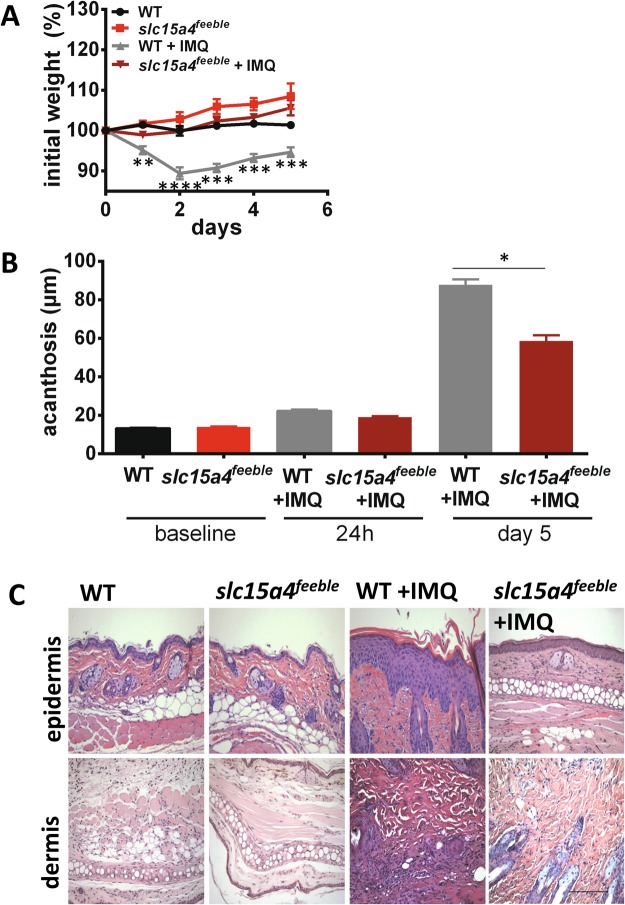

We applied IMQ or vehicle control to the shaved backs of WT and slc15a4feeble (slc15a4 deficient mice) for 4 consecutive days and terminated the experiment on day 5 to be consistent with most IMQ studies19. Dramatically, slc15a4feeble mice grossly appeared unaffected by IMQ, i.e. no hunching, withered appearance or decrease in movement was observed in contrast to their WT littermates. Consistently, IMQ-induced weight loss was not observed in slc15a4feeble as compared to WT mice (Fig. 1A). Similarly, skin punch biopsies demonstrated attenuated acanthosis in slc15a4feeble compared to WT mice as early as 24 hours post IMQ (Fig. 1B). This difference in skin thickening was greater by day 5 (Fig. 1B and C). To determine the specificity of slc15a4 in this psoriasiform model, we executed a more chronic model of psoriasiform dermatitis that activates the downstream inflammatory cascade by direct intralesional injection of IL23 which promotes Th17 skewing. We found that after 11 days, slc15a4feeble had increased ear skin thickness as compared to their WT littermates (Fig. 2A) and acanthosis similar to that induced by IMQ in WT mice (Fig. 2B). Thus, we reasoned that a slc15a4 pro-inflammatory role was necessary in the IMQ model potentially by driving a very proximal event in the inflammatory pathway (i.e. pDC sensing of IMQ).

Figure 1.

slc15a4 is required for imiquimod induced weight loss and epidermal thickening. slc15a4feeble and WT mice were treated with imiquimod (IMQ) and euthanized after 24 hours or 5 days. (A) Significant IMQ-induced weight loss was observed in WT mice as compared to slc15a4feeble mice (n = 7, 5, 17, 15). (B) Attenuated IMQ-induced acanthosis was observed in slc15a4feeble mice at 24 hours and 5 days post daily IMQ treatment compared to WT mice (n = 7, 5, 6, 6, 17, 5). (C) Representative images of H&E stained mouse dorsal skin from WT and slc15a4feeble mice demonstrated attenuated acanthosis in slc15a4feeble mice compared to WT mice on day 5 (n = 7, 5, 17, 15). Images taken at 200 × . Scale is the same in all pictures; scale bar = 100 µm. Data combined from 3 independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001 in unpaired two-sided parametric T tests.

Figure 2.

s1c15a4feeble mice exhibit increased inflammation of the ear following intralesional injections of IL23. Ears of WT and slc15a4feeble mice were injected every other day for 16 consecutive days with 20uL PBS containing 500 ng IL23. (A) On day 16, ears were collected for staining and measurement via H&E. (B) Ears were measured every other day with a micrometer, before injections (n = 7, 7, 6). (C) Representative H&E sections of mouse ears following treatment with IL23 (n = 7, 7, 6, 6). Images taken at 200x. Scale is the same in all pictures; scale bar = 100 µm. Data from two independent experiments each containing 6–7 mice/group. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001 in unpaired two-sided parametric T tests.

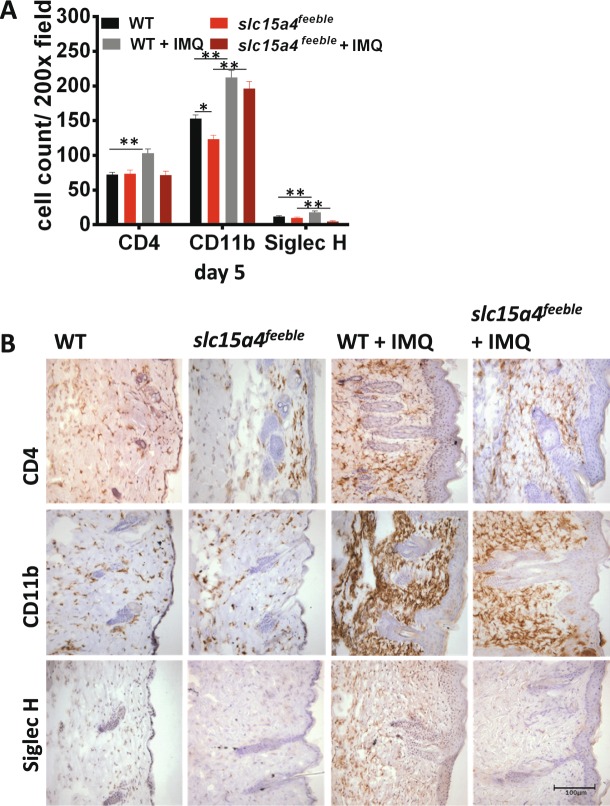

slc15a4 is required for IMQ-induced recruitment of CD4+ and SiglecH+ cells

The IMQ model of psoriasiform dermatitis is driven by cytokine secreting CD4+ T cells of the lymphoid compartment in addition to CD11b+ myeloid cells26,27. These cell types are critical for the local and systemic effects of IMQ that we observed (Fig. 1). Thus, we compared the inflammatory infiltrate between treated and control WT and slc15a4feeble mice on day 5 of IMQ treatment to determine if there was a difference in inflammatory cell infiltration by immunohistochemistry (IHC). We also quantitated the presence of the pDC marker SiglecH given the specific loss of function of pDC in slc15a4 deficient mice. We observed an absence of CD4+ and SiglecH+ cells accumulating in the treated skin of slc15a4feeble mice as compared to littermate controls by day 5 (Fig. 3A,B). These data implicated CD4+ T lymphocytes and pDC as potential cell types driving IMQ-driven weight loss and acanthosis via slc15a4. In contrast, there was an essentially normal accumulation of CD11b+ cells in slc15a4feeble vs. WT mice. Albeit, slc15a4feeble had a slightly lower absolute number of resident CD11b+ myeloid cells at baseline (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

IMQ-dependent recruitment of CD4 + T cells into the dermis requires slc15a4. slc15a4feeble and WT mice were shaved and treated with imiquimod (IMQ) or only shaved and euthanized after 5 days. (A) Quantitative measurements of CD4 T-cell (CD4), myeloid cell (CD11b) and pDC (Siglec H) infiltrate from immunostained dorsal mouse skin of WT and slc15a4feeble mice 5 days post topical treatment with IMQ or control. n = 4, 5, 4, 5 mice for WT, slc15a4feeble, WT + IMQ, slc15a4feeble + IMQ, respectively. (B) Representative immunostained sections of dorsal mouse skin at 6 days post treatment with IMQ. n = 4, 5, 4, 5 images from left to right. Images taken at 200x. Scale is the same in all pictures; scale bar = 100 µm. Data is from 1 of 3 similar experiments with 4–5 mice/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, in unpaired two-sided parametric T tests.

slc15a4 is required for IFN-I induction

pDC secrete ~1000x more IFN-I than any other cell type. Consistently, pDC are responsible for ~50% of all circulating IFN-I during acute viral infections despite being extremely rare cells6. Given the absence of SiglecH + pDC accumulating in slc15a4feeble, and the central role of pDC in IMQ responses28–30, we hypothesized that slc15a4 would be required for IMQ-induced IFN-I. We found that the loss of slc15a4 accounted for >1.5 log decrease in IFN-I production (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

slc15a4 is required for type 1 interferon induction. Plasma was collected 6 and 9 hours post IMQ from WT and slc15a4feeble mice. IFN-I levels were than measured by ELISA. n = 4/group. 1 of 2 similar experiments shown. ***p < 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001 in unpaired two-sided parametric T tests.

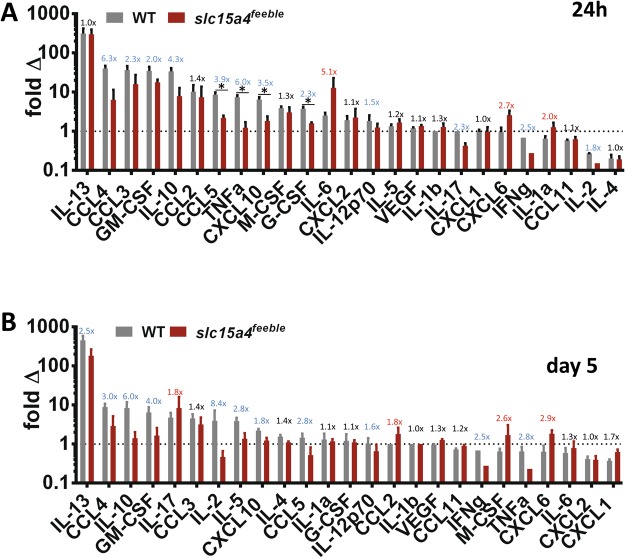

slc15a4 contributes to systemic cytokine storm during topical IMQ treatment

IFN-I treatment is known to cause weight loss and general malaise that is associated with general inflammation31. Thus, we reasoned that IMQ-induced systemic IFN-I would likely propagate a broad induction of circulating inflammatory cytokines (“cytokine storm”). We measured 25 cytokines to address this possibility (Fig. 5). We found a potent induction of almost all 25 cytokines by IMQ. This induction was either unchanged or attenuated in slc15a4feeble. This attenuation was not generally due to a higher steady state concentration of cytokines in slc15a4feeble as absolute plasma concentrations were overall very similar as compared to WT mice (Supp. Fig. 5). Only CXCL6(24 h and day 5), IL-1a (24 h only) and IL-6 (24 h only) were increased in slc15a4feeble as compared to WT mice. These cytokines share a common nidus, inflammasome activation32,33. Induction of IL1b (the canonical output of the inflammasome) did not meet statistical significance, although it did trend in the same direction (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

slc15a4 contributes to IMQ driven cytokine storm. Inflammatory cytokine plasma concentrations were measured following IMQ treatment using a 25-cytokine luminex assay. Fold changes (IMQ-treated at the indicated timepoint/time = 0) are shown at 24 hours (A) and 5 days (B). Cytokines were rank-ordered for IMQ-induction in WT. The dotted line represents where IMQ treatment does not affect circulating cytokine levels. The ratio of IMQ-induced fold changes are displayed in blue (decreased), red (increased) and black (<1.5x changed) comparing mutant to WT. Data was combined from three independent experiments with a total of 5–13 mice per group. *p < 0.05 in unpaired T-test after multiple comparison correction.

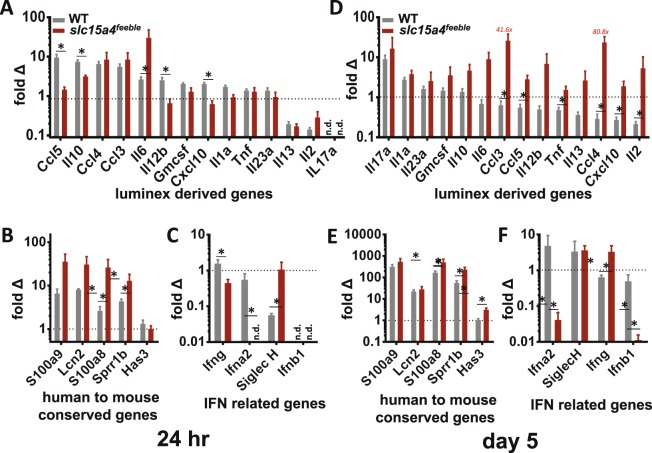

Unexpected more potent induction of trademark psoriasiform genes and inflammatory cytokines in skin of slc15a4 deficient mice

Lastly, we asked whether the IMQ-treated skin may contribute to the systemic increase in circulating cytokines. To address this we isolated total RNA from the treated skin 24 hours and on day 5 post initiation of treatment and quantitated gene expression for those cytokines identified in the luminex assay above, with validated TaqMan primer-probesets available. We added IL12b and IL23a given their central role in psoriasiform inflammation as the canonical gene products driving Th1 and Th17 skewing, respectively34. To further evaluate inflammasome associated genes, review of the literature demonstrated IL1f6 (IL-36a) and CXCL5 as additional IMQ-induced gene products35,36. RT-qPCR demonstrated induction of many of these cytokines at 24 h in WT mice (Fig. 6A) similar to what we observed in the plasma (Fig. 5A). However, this local skin induction was largely absent by day 5, consistent with downstream elaboration of circulating cytokines by immune cells which have left the treated skin in WT mice (Fig. 6A). This correlation with plasma proteins included the relative increase of inflammasome-related genes in in slc15a4feeble compared to WT mice (Figs 5A and 6A) in addition to a moderate increase in the Th1 and Th17 skewing gene products IL12b and IL23a, respectively. Surprisingly, we found more potent gene induction of inflammatory cytokines within the skin of overall less-inflamed slc15a4feeble mice by day 5 (Figs 5B and 6D). This could not be generally explained by lower basal gene expression in slc15a4feeble mice (Fig. 6S). Taken together, we concluded that local skin gene induction of inflammatory cytokines may play a role in the first day of IMQ treatment. However, by day 5 the absence of weight loss and diminished cytokine storm in slc15a4feeble could not be correlated with local gene expression. Thus, we reasoned that local gene expression could not serve as the predominant source for circulating cytokines on day 5. We than measured the most strongly increased trademark psoriasisform genes conserved across humans and 5 mouse models of psoriasiform dermatitis (including IMQ-induced)35 (Fig. 6B,E). Despite diminished IMQ-induced acanthosis in slc15a4feeble (Fig. 1), we found more potent induction of the 5 most induced genes conserved across animal models and human psoriasis at 24 h and this increase was maintained on day 5 (Fig. 6B,E). We then confirmed that the genes whose regulation were most diminished in magnitude and over time in slc15a4feeble were the type I interferon genes: Ifna2 and Ifnb1 but not type II interferon (gamma) (Fig. 6C,F). Thus, we concluded that increased induction of psoriasis-associated genes is not sufficient for maximal skin thickening and that diminished IFN-I, both local and systemic, was the most likely culprit.

Figure 6.

Unexpected more potent induction of trademark psoriasiform genes and inflammatory cytokines over time in skin of slc15a4 deficient mice. RT-qPCR analysis of inflammatory genes elevated in 25plex cytokine analyses in IMQ-treated mice 24 hours (A) and 5 days (D) post treatment with IMQ. IL12b and IL23a were added to address Th1 and Th17 skewing, respectively. Cytokines were rank ordered from greatest to least induction in WT. Expression of trademark psoriasiform genes conserved between human and 5 mouse models is shown rank ordered for human psoriasis at 24 hours (B) and 5 days (E) post-treatment with IMQ. Otherwise, all other datasets are rank ordered for WT mouse induction. IFN-associated genes are shown 24 hours (C) and 5 days (F) post-treatment with IMQ. Fold change = IMQ relative quantity (RQ)/control RQ, see Materials and Methods for further details. Data is representative of 3 combined experiments with 5–13 mice/group. n.d. = not detected. *p < 0.05 in unpaired T-test after multiple comparison correction.

Discussion

The role of IFN-I in the IMQ model of psoriasiform dermatitis is controversial5,20,22,23. The most potent producer of IFN-I is the very rare pDC cell type. Thus efforts to target this cell type systemically for elimination can be difficult to access throughout the animal given the potential critical effects of even a few remaining cells. Additionally, compensatory responses are possible in the absence of this cell type. Therefore, we chose an alternative approach to access a potential therapeutic intervention for pDC-TLR7 driven immune pathology, genetic disruption of slc15a4. Slc15a4 is required for pDC TLR7/9 sensing and subsequent TLR driven IFN-I production7. We and others previously found that this pathway was important in disease models11,18,37. Therefore, we hypothesized that studying slc15a4 deficiency in the IMQ-induced psoriasiform dermatitis model may serve as an alternative strategy to specifically disrupt this pathway. These experiments also demonstrate the potential utility of targeting slc15a4 therapeutically. slc15a4feeble mice, lacking pDC sensing, exhibited attenuated local and systemic IMQ effects compared to WT mice.

It is also possible that the effect of slc15a4 deficiency is mediated in part via B cells. However, this is less likely as the reported effects of slc15a4 deficiency in B cells generally occur later than the phenotypes described here in an acute 5 day IMQ model. The only other cell type reported to be affected directly by slc15a4 deficiency is mast cells. However, slc15a4−/− mast cells degranulate more potently than their WT counterparts38 which would not explain our overall observations.

Given the acute effects of IMQ are largely driven via pDC TLR7 sensing28–30, we suspect that pDCs mediate the majority of the phenotype in slc15a4feeble. However, the opposite phenotype found in the IL23 model could involve B cells and/or mast cells. These cell types (especially mast cells in the acute setting) may participate in the apparently paradoxical observation of increased inflammasome-related systemic inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 5) and the unexpected increase in cutaneous pro-inflammatory gene expression (Fig. 6). Another explanation for these surprising findings could be inflammatory gene expression compensatory feedback in the absence of IFN-I, the latter of which is likely necessary for acanthosis as IFN-I protein and gene expression was consistently the most decreased pathway in slc15a4feeble compared to WT mice.

Although slc15a4 is tightly expressed in DC and B cells, we considered the possibility that slc15a4feeble may have behavioral differences that contributed to our phenotypes19. However, no difference in grooming behaviors were observed between slc15a4feeble and WT mice. Additionally, IMQ was applied until it was fully absorbed via visual inspection to help ensure that any inflammatory differences between WT and mutant mice were not confounded by differential uptake of IMQ or uptake via a different route (i.e. orally).

To understand the basis for the striking absence of weight loss in comparison to the more modest skin changes in slc15a4feeble, we examined circulating inflammatory cytokines as a possible explanation. We found diminished induction of 11/25 and 7/25 IMQ-induced circulating cytokines (24 h and day 5, respectively) that supported this hypothesis (Fig. 5). In addition, the most sustained inflammatory defect in slc15a4feeble was an absence of IFN-I induction observed at all times at the level of protein and RNA expression when IFN-I is most prominently induced both systemically and locally (Figs 4 and 6). We suspect that the absence of weight loss in slc15a4feeble during IMQ treatment is likely due to reduced IFN-I and/or other cytokines in circulation. Strikingly, three cytokines were upregulated at 24 h and 5 days post IMQ treatment in slc15a4feeble versus WT mice. These were all inflammasome-related cytokines32,33,39,40. The IMQ psoriasiform model is mediated by the TLR7 vs. inflammasome pathways20. slc15a4 is required for TLR7 sensing via pDC consistent with diminished acanthosis, weight loss (Fig. 1), immune cell recruitment (Fig. 3), cytokine storm (Figs 4 and 5) and cutaneous induction of several genes at 24 h (Fig. 6). However, some inflammation remained in slc15a4 during IMQ topical treatment as measured by acanthosis (Fig. 1) with preserved recruitment of myeloid immune cells (Fig. 3). Our data supports the activation of the inflammasome as a potential etiology for this residual acanthosis whose activation is independent of slc15a4 consistent with its reported function. Specifically, the relatively heightened concentration of inflammasome-related cytokines in the plasma (Fig. 5) and inflammasome-related genes in the treated skin (Fig. 6) support a molecular basis for residual IMQ-induced inflammation without pDC-TLR7 sensing. Residual markers of molecular inflammation in slc15a4feeble was most striking for the trademark genes whose induction is conserved across human psoriasis and mouse models35 at 24 h and subsequently, most inflammatory cytokines surveyed on day 5 (Fig. 6). Taken together, we reason that pDC-TLR7 sensing can be targeted via slc15a4 and is critical for the inflammatory cascade which results in significant morbidity and weight loss in the IMQ model of psoriasisform dermatitis. In this IMQ-induced model, loss of slc15a4 is most tightly tied to a defect in IFN-I production while an inflammasome signature is preserved.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All mice used in this study were housed in the Case Western Reserve University Biomedical Research Building Animal Facility. C57BL/6 J mice were bred locally or ordered from Jackson Laboratories. slc15a4feeble/feeble (MGI: 4835997) mutants have been described previously7.

Imiquimod challenge model

Briefly, slc15a4feeble and C57BL/6 J mice were used at 6–8 wks of age and gender did not determine different outcomes. Mouse dorsal skin was treated with IMQ, for 1 day or 5 consecutive days, followed by harvest of tissue and plasma. The dorsal skin of wildtype and feeble mice were shaved prior to IMQ application. 0.05 g/mouse of IMQ cream (5%), vehicle only, or no cream was applied to the shaved skin of the mice. Clinical phenotypes (weight loss and acanthosis as described previously19) were identical between vehicle only and no cream conditions.

IL23 challenge model

Briefly, slc15a4feeble and C57BL/6 J mice were used at 6–8 wks of age and gender did not affect different outcomes. Mice received intralesional injections of 20 μl PBS, either alone or containing 500 ng recombinant mouse IL-23 (eBioscience), using a 26-gauge needle every other day for 16 days as previously described41. Ear thickness was measured via micrometer before injection on day 0 and thereafter on days without injections.

Immunohistochemistry

Skin was embedded fresh in Tissue Freezing Media (TFM; Triangle Biomedical), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and immediately stored at −80 °C. Remaining treated dorsal skin was flash frozen and stored at −80 °C for use in RNA experiments. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 8 μm sections. Antibodies and isotype controls were detected using either rabbit anti-rat IgG biotinylated or goat anti-rabbit IgG biotinylated, amplified with Avidin/Biotinylated Enzyme Complex (ABC, Vector) and were visualized using the enzyme substrate diaminobenzidine (Vector). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and imaged as previously described42. Three different observers have quantified each image manually on two occasions.

RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

Dorsal skin was homogenized in TRIzol using a Mikro-Dismembrator (Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Edgewood, NY) and RNA isolated using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR was than performed using TaqMan microfluidic array technology from Applied Biosystems on an ABI 7900HT. Relative Quantity (RQ) expression levels were calculated using the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT) and normalized by GAPDH for: Ifn-gamma, Ifn-beta, Siglec H, Gmcsf, Il-2, Il-7, Il-10, Ccl5, Ccl3, Ccl4, Il-13, Il-23, S100a7a, S100a9, S100a8, Cxcl1010, IL-1f6, Tnf-a, Il-12p40, Serpinb3c, IL-1 alpha, Has3, Lcn2, Sprr1b, Pcdh21, Icos, Il-17, Ccl5, Ifna2, and Lor. Absolute values of all measured genes, at baseline and induction, is described in the Supplementary Figures 1, 2.

Analysis of circulating cytokines

Plasma collected at 24 h and 5 days was interrogated with a 25plex luminex screening assay (R&D systems) on a Biorad Bioplex Magpix Multiplex Luminex Microplate Reader by the CWRU Bioanalyte core for IL-12p70, VEGF, IL-1beta, CCL2, CXCL2, IL-6, IL-4, IL-2, TNFalpha, CXCL1, IL-17, IL-10, IL-13, IL-5, IFNgamma, CXCL10, CCL5, G-CSF, M-CSF, CCL4, IL-1alpha, CCL3, GM-CSF, CXCL6, and CCL11. IFN-I was measured in plasma by ELISA per manufacturer’s instructions (PBL Assay Science). Absolute values of all measured circulating cytokines, at baseline and induction, is described in the Supplementary Figures 3–8.

Statistical Analysis

Unpaired two-sided parametric T-tests were performed between WT and WT + IMQ groups at each time point in addition to comparing slc15a4feeble and slc15a4feeble + IMQ groups where indicated. When more than 4 groups were compared, statistical significance was determined using the Holm-Sidak method to correct for multiple comparisons with alpha = 5%, as indicated. Each row was analyzed individually, without assuming a consistent SD.

Ethical Approval

Experimental protocols were approved by Case Western Reserve University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) institutional committee under IACUC protocol # 2014-0106. Specifically, Less than 5 mice were housed per cage with daily monitoring to ensure optimal animal welfare and to ameliorate suffering. All mouse studies have been conducted according to national and international guidelines and in accordance with institutional regulations governing animal care and useas detailed in IACUC# 2014-0106.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the Skin Diseases Research Center P30AR039750, VA Merit Award IBX002719A, American Skin Association Carson Scholars Fund, the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, and UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. These contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or other funding sources.

Author Contributions

A.D.G., A.K.Z., M.H., R.D. and D.L.P. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: D.L.P. Analysis and interpretation of data: A.D.G., A.K.Z., M.H., R.D., D.L.P. Drafting of the manuscript: A.D.G., A.K.Z., D.L.P. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: A.K.Z., R.D., D.L.P. Obtained funding: D.L.P. Administrative, technical, or material support: A.D.G., A.P., J.Y., M.H., R.D. Study supervision: D.L.P.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32668-9.

References

- 1.Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003-2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilliet M, et al. Psoriasis triggered by toll-like receptor 7 agonist imiquimod in the presence of dermal plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1490–1495. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lande R, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature. 2007;449:564–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestle FO, et al. Plasmacytoid predendritic cells initiate psoriasis through interferon-alpha production. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;202:135–143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wohn, C. et al. Langerin(neg) conventional dendritic cells produce IL-23 to drive psoriatic plaque formation in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America110, 10723–10728, 10.1073/pnas.1307569110(2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Swiecki M, Colonna M. Unraveling the functions of plasmacytoid dendritic cells during viral infections, autoimmunity, and tolerance. Immunological Reviews. 2010;234:142–162. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasius AL, et al. Slc15a4, AP-3, and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome proteins are required for Toll-like receptor signaling in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:19973–19978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014051107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasawatari S, et al. The Solute Carrier Family 15A4 Regulates TLR9 and NOD1 Functions in the Innate Immune System and Promotes Colitis in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1513–1525. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamashita T, et al. Cloning and functional expression of a brain peptide/histidine transporter. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:10205–10211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.10205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dosenovic P, et al. Slc15a4 function is required for intact class switch recombination to IgG2c in response to TLR9 stimulation. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2015;93:136–146. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baccala R, et al. Essential requirement for IRF8 and SLC15A4 implicates plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of lupus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:2940–2945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222798110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han JW, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1234–1237. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He CF, et al. TNIP1, SLC15A4, ETS1, RasGRP3 and IKZF1 are associated with clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus in a Chinese Han population. Lupus. 2010;19:1181–1186. doi: 10.1177/0961203310367918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, et al. Genes identified in Asian SLE GWASs are also associated with SLE in Caucasian populations. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2013;21:994–999. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HS, et al. Ethnic specificity of lupus-associated loci identified in a genome-wide association study in Korean women. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2014;73:1240–1245. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-20267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuo XB, et al. Variants in TNFSF4, TNFAIP3, TNIP1, BLK, SLC15A4 and UBE2L3 interact to confer risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in Chinese population. Rheumatology International. 2014;34:459–464. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2864-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang MW, Chen FR, Zhang DM, Zhai ZF, Hao F. Association Study Between SLC15A4 Polymorphisms and Haplotypes and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a Han Chinese Population. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 2016;20:451–458. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2015.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blasius, A. L., Krebs, P., Sullivan, B. M., Oldstone, M. B. & Popkin, D. L. Slc15a4, a Gene Required for pDC Sensing of TLR Ligands, Is Required to Control Persistent Viral Infection. Plos Pathogens8, 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002915 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Hawkes JE, Gudjonsson JE, Ward NL. The Snowballing Literature on Imiquimod-Induced Skin Inflammation in Mice: A Critical Appraisal. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2017;137:546–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter, A. et al. Aldara activates TLR7-independent immune defence. Nature Communications4, 10.1038/ncomms2566 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Pantelyushin S, et al. Ror gamma t(+) innate lymphocytes and gamma delta T cells initiate psoriasiform plaque formation in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122:2252–2256. doi: 10.1172/JCI61862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grine L, Dejager L, Libert C, Vandenbroucke RE. Dual Inhibition of TNFR1 and IFNAR1 in Imiquimod-Induced Psoriasiform Skin Inflammation in Mice. Journal of Immunology. 2015;194:5094–5102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gui J, et al. Therapeutic Elimination of the Type 1 Interferon Receptor for Treating Psoriatic Skin Inflammation. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2016;136:1990–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.06.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kader, M. et al. Blocking TLR7-and TLR9-mediated IFN-alpha Production by Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Does Not Diminish Immune Activation in Early SIV Infection. Plos Pathogens9, 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003530 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Kobayashi T, et al. The Histidine Transporter SLC15A4 Coordinates mTOR-Dependent Inflammatory Responses and Pathogenic Antibody Production. Immunity. 2014;41:375–388. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flutter B, Nestle FO. TLRs to cytokines: Mechanistic insights from the imiquimod mouse model of psoriasis. European Journal of Immunology. 2013;43:3138–3146. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa S, et al. Role of MyD88 signaling in the imiquimod-induced mouse model of psoriasis: focus on innate myeloid cells. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2017;102:791–803. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibson SJ, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce cytokines and mature in response to the TLR7 agonists, imiquimod and resiquimod. Cell Immunol. 2002;218:74–86. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8749(02)00517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajagopal D, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell-derived type I interferon is crucial for the adjuvant activity of Toll-like receptor 7 agonists. Blood. 2010;115:1949–1957. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemmi H, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196–200. doi: 10.1038/ni758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seyam MS, Freshwater DA, O’Donnell K, Mutimer DJ. Weight loss during pegylated interferon and ribavirin treatment of chronic hepatitis C*. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wuyts A, et al. The CXC chemokine GCP-2/CXCL6 is predominantly induced in mesenchymal cells by interleukin-1beta and is down-regulated by interferon-gamma: comparison with interleukin-8/CXCL8. Lab Invest. 2003;83:23–34. doi: 10.1097/01.LAB.0000048719.53282.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Netea MG, van de Veerdonk FL, van der Meer JWM, Dinarello CA, Joosten LAB. Inflammasome-Independent Regulation of IL-1-Family Cytokines. Annual Review of Immunology Vol. 2015;33(33):49–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng YX, Chang C, Lu QJ. The Inflammatory Response in Psoriasis: a Comprehensive Review. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2016;50:377–389. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swindell, W. R. et al. Genome-Wide Expression Profiling of Five Mouse Models Identifies Similarities and Differences with Human Psoriasis. Plos One6, 10.1371/journal.pone.0018266 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Johnston A, et al. IL-1F5, F6, F8, and F9: a novel IL-1 family signaling system that is active in psoriasis and promotes keratinocyte antimicrobial peptide expression. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2010;130:S43–S43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kioon, M. D. A. et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells promote systemic sclerosis with a key role for TLR8. Science Translational Medicine10, 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam8458 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Kobayashi T, et al. Lysosome biogenesis regulated by the amino-acid transporter SLC15A4 is critical for functional integrity of mast cells. International Immunology. 2017;29:551–566. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxx063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biondo C, et al. The Interleukin-1 beta/CXCL1/2/Neutrophil Axis Mediates Host Protection against Group B Streptococcal Infection. Infection and Immunity. 2014;82:4508–4517. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02104-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parry GCN, Martin T, Felts KA, Cobb RR. IL-1 beta-induced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene expression in endothelial cells is blocked by proteasome inhibitors. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. 1998;18:934–940. doi: 10.1161/atvb.18.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hedrick MN, et al. CCR6 is required for IL-23-induced psoriasis-like inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2317–2329. doi: 10.1172/JCI37378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swindell WR, et al. Imiquimod has strain-dependent effects in mice and does not uniquely model human psoriasis. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2017;137:S111–S111. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0415-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.