Abstract

Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), on the basis of lymphocyte, neutrophil and platelet counts had been published to be a good prognostic factor in multiple cancers. Nevertheless, the prognostic value of SII in cancer patients remains inconsistent. Therefore, we carried out a meta-analysis to evaluate the prognostic value of SII in these patients with cancer. A total of 22 articles with 7657 patients enrolled in this meta-analysis. The combined result revealed that a high SII was evidently correlated with poor overall survival (OS) (HR=1.69, 95%CI=1.42-2.01, p<0.001), poor time to recurrent (TTR) (HR=1.87, p<0.001) , poor progress-free survival (PFS) (HR=1.61, p=0.012) ,poor cancer-specific survival (CSS) (HR=1.44, p=0.027) , poor relapse-free survival (RFS) (HR=1.66, p=0.025) and poor disease-free survival (DFS) (HR=2.70, p<0.001) in patients with cancers. Subgroup analysis indicated that SII over the cutoff value could predict worse overall survival in Hepatocellular carcinoma (p<0.001), Gastric cancer (p=0.005), Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (p=0.013), Urinary system cancer (p<0.001), Small cell lung cancer (p<0.001), Non-Small cell lung cancer (p<0.001) and Acral Melanoma (p<0.001). The largest effect size was observed in the Hepatocellular carcinoma (HR=2.11). In addition, these associations did not vary significantly by the cutoff value, sample size and ethnicity. Therefore, high SII may be a potential prognostic marker in patients with various cancers and associated with the poor overall outcomes.

Keywords: Systemic immune-inflammation index, cancer, prognosis, meta-analysis

Introduction

According to the WHO, cancer is still the second leading cause of death worldwide, and was responsible for 8.8 million deaths in 2015. Globally, an almost one-in-six death is due to cancer 1. Cancer is a generic terminology for a large group of diseases which can influence any part of the body. Recurrence and metastasis are the major causes of death and poor outcome for cancer. Therefore, it is pivotal for us to identify better predictors for prognosis in patients with cancer.

It is well known that inflammation can increase tumor risk and influence all tumor stages, triggering the initial genetic mutation or epigenetic mechanism, promoting tumor initiation, metastasis and progression 2. Thus, inflammation parameter is a powerful candidate to predict cancer outcome. In recent years, many inflammatory markers, such as C-reaction protein (CRP), neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) have been studied in association with poor prognosis of cancers 3-6.

Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII),a new inflammatory index, based on neutrophil, platelet and lymphocyte counts has been recently suggested to be associated with poor outcome in Hepatocellular carcinoma 7, Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma8,Small Cell Lung Cancer9,and so on. However, due to the different of the study design or sample size, there are still some contrary views 10, 11. The association between SII and cancer prognosis is controversial.

Therefore, it is necessary for us to estimate the prognostic value of SII in patients with cancer. Thus, in this study, we performed a meta-analysis to investigate the prognostic role of SII in patients with various cancers.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

The Pubmed, Embase, PMC, Web of Science and Cochrane Library databases were searched up to February 15, 2018 with the search strategy ( SII OR “Systemic immune-inflammation index”) AND (cancer OR tumor OR carcinomas OR neoplasm) AND (prognosis OR outcome OR mortality OR survival OR recurrence OR metastasis OR progression) by two independently authors (RN Yang and Q Chang). The language was limited to English.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follow: (1) the roles of SII in cancer patients were investigated. (2) Pretreatment SII and cutoff values were reported. (3) SII was used as prognostic indicators of OS, CSS or PFS or TTR or DFS or RFS. (4) Sufficient data for the computation of hazard ratios (HR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported.

The exclusion criteria are the following: (1) duplicate publications. (2) Review, conference abstract, letter, not full text in English. (3) Studies with insufficient data. (4) Animals studies.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors independently evaluated the survival data and study characteristics from the selected articles that met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by third individual.

The quality of studies was evaluated by Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment Scale (NOS) 39, which includes 3 parts: assessment of selection of the exposed and unexposed cohort (0-4 points), comparability of the two cohorts (0-2 points), and outcome assessment (0-3 points) and they were summarized in supplement material (Table S1). The scores ranged from 0 to 9 points, with≥6 points denoting high quality.

Statistical analysis

Pooled HRs and 95% CIs were extracted from each study to assess prognostic role of SII in cancer patients. Heterogeneity among studies was tested by Cochran's Q test and the Higgins'I2 statistic. If the I2≥50% and P<0.05, random-effects models was used to generate the pooled HRs, if not, fixed-effects were performed. Egger's test and Begg's test were applied to evaluate publication bias. Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the stability of the results. All statistical analyses were conducted with STATA version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Search results and characteristics of the included study

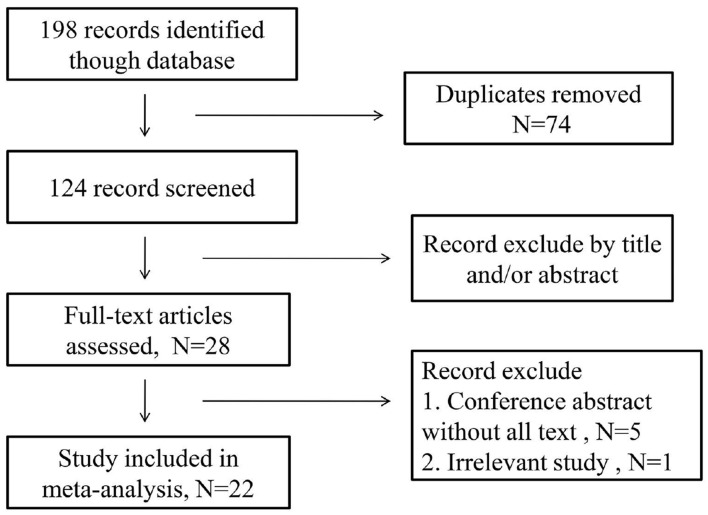

As is shown in the Figure 1, initially 198 records were identified through the electronic database. After removed duplicates and excluded by title and/or abstract, 28 articles were selected. In these 28 articles, 5 articles were conference abstract without full text, and another was irrelevant records. Therefore, there were 22 articles involving 7657 patients enrolled. In these included articles, 20 articles conducted retrospective analysis, one of them performed Propensity Score-matched retrospective Analysis, one article conducted prospective analysis and the last one had both a retrospective design and a prospectively design in two independent patients population. Therefore, a total of 22 articles including 24 studies were included in this analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chat of the study search and selection.

As is listed in Table 1, all articles were published between 2014 and 2017 in English peer-reviewed journals. Among these articles, 16 articles 7-12, 14, 17, 20-25, 27, 28 were from China, 4 articles 13,15,16,19 were from Italy, one was from Korea18 and another was from France26. These articles included a variety of cancers, among them 6 for Hepatocellular carcinoma, 3 for Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), 3 for Gastric Cancer, 3 for colorectal cancer, one for Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC), one for Prostate cancer, one for Renal cell cancer, one for Biliary tract cancer, one for Malignant obstructive jaundice, one for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and one for Acral Melanoma.. As shown in Table 1, the reference of 7 and 8 were performed in two independent patient populations, they separately had two HRs. Thus we expressed them in this way that “one article but two studies”. Therefore, a total of 22 articles but 24 studies enrolling 7657 patients were included in this manuscript. Among them, 20 articles but 22 studies involving 7196 patients reported OS, 3 articles but 4 studies including 602 patients reported TTR, 5 articles comprising 1205 patients reported PFS and respectively, 298, 280 and 226 patients reported CSS, DFS and RFS. The cutoff value of SII in these articles was not uniform and ranged from 300 to1600, sample size varied from 33 to 919 with a medium sample size of 560. As for the quality evaluation of selected studies, the NOS of nine included articles was 9, nine included articles was 8 and four was 7.

Table 1.

The characteristics of included studies

| Study | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Cancer type | Sample size | Cutoff value | Outcome | NOS | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu[7] | 2014 | China | Asian | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 123 and133 | 330 | OS, TTR | 8 | M |

| Liu[11] | 2015 | China | Asian | Gastric Cancer | 455 | 660 | OS | 8 | M |

| Yang[12] | 2015 | China | Asian | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 189 | 300 | OS | 9 | M |

| Hong[9] | 2015 | China | Asian | Small Cell Lung Cancer | 919 | 1600 | OS | 8 | M |

| Gardini[13] | 2016 | Italy | Caucasian | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 56 | 360 | OS,PFS | 9 | M |

| Wang[14] | 2016 | China | Asian | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 163 | 330 | TTR | 8 | M |

| Geng[8] | 2016 | China | Asian | ESCC | 916 and 759 | 307 | OS | 8 | M |

| Loll[15] | 2016 | Italy | Caucasian | Prostate cancer | 230 | 535 | OS | 9 | M |

| Loll[16] | 2016 | Italy | Caucasian | Renal cell cancer | 335 | 730 | OS, PFS | 8 | M |

| Huang[17] | 2016 | China | Asian | Gastric Cancer | 455 | 572 | OS | 7 | M |

| Ha[18] | 2016 | Korea | Asian | Biliary tract cancer | 158 | 572 | OS | 9 | M |

| Gao[10] | 2016 | China | Asian | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 183 | 330 | OS,TTR | 8 | U |

| Passardi[19] | 2016 | Italy | Caucasian | Colorectal cancer | 289 | 730 | OS, PFS | 7 | M |

| Jin[20] | 2017 | China | Asian | MBJ | 33 | 644 | OS | 9 | M |

| Feng[21] | 2017 | China | Asian | ESCC | 298 | 410 | CSS | 8 | M |

| Tong[22] | 2017 | China | Asian | non-small cell lung cancer | 332 | 660 | OS | 9 | M |

| wang[23] | 2017 | China | Asian | Gastric Cancer | 444 | 660 | OS | 9 | M |

| Yang [24] | 2017 | China | Asian | Colorectal cancer | 95 | 460.66 | OS,PFS | 9 | U |

| Yu[25] | 2017 | China | Asian | Acral Melanoma | 226 | 615 | OS, RFS | 9 | M |

| Conroy[26] | 2017 | France | Caucasian | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 156 | 600 | OS | 8 | M |

| Wang[27] | 2017 | China | Asian | ESCC | 280 | 560 | OS, DFS | 7 | M |

| Chen[28] | 2017 | China | Asian | Colorectal cancer | 430 | 340 | OS,PFS | 7 | M |

Abbreviations: ESCC: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; MBJ: Malignant obstructive jaundice; OS: overall survival; PFS: progress-free survival; TTR: time to recurrent; CSS: cancer-specific survival; RFS: elapse-free survival; DFS: disease-free survival; U: univariate; M: multivariate; NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Meta-analysis results

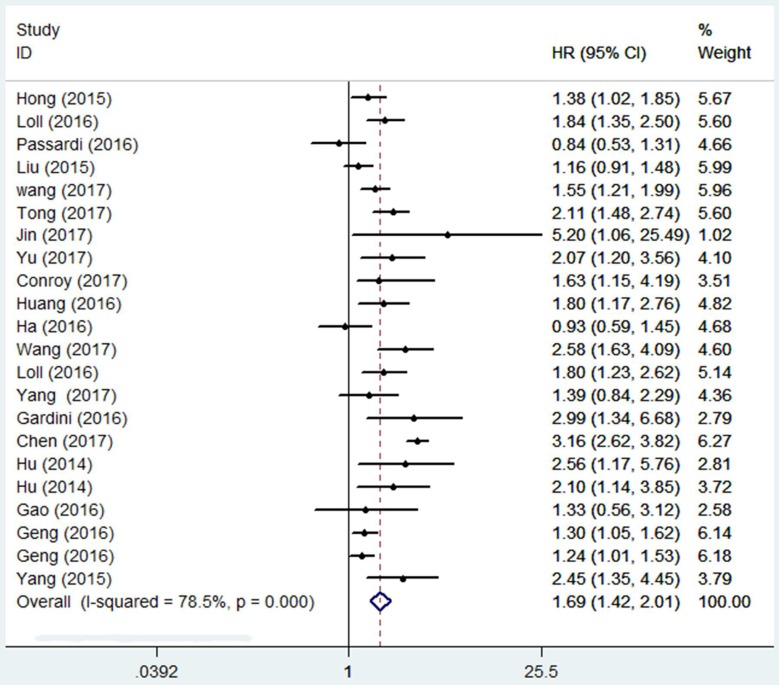

Overall survival

A total of 7196 patients were included in the analysis of HR for OS. As shown in Figure 2. The combined result revealed that in comparison with a low SII , a high SII was evidently correlated with poor OS (HR=1.69, 95%CI=1.42-2.01, p<0.001), and because of obvious heterogeneity (I2 = 78.5%, Ph = 0.000), a random-effect model was applied. Subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate HR of OS by ethnicity, cancer type, sample size, cutoff value (Table 2). In the subgroup analysis by cancer type, high SII predicted poor OS in Hepatocellular carcinoma (HR=2.11, 95%CI=1.59-2.80, p<0.001), Gastric Cancer (HR=1.43, 95%CI=1.12-1.83, p=0.005), ESCC (HR=1.5, 95%=1.09-2.06, p=0.013), Urinary tract cancer (HR=1.82, 95%CI=1.44-2.32, p<0.001), and other cancers include SCLC, Acral Melanoma and NSCLC (HR=1.77, 95%CI=1.30-2.41, p<0.001) and good effect size was observed in the hepatocellular carcinoma (HR=2.11) . Overall prognostic ability of SII was low in g Gastric Cancer and ESCC (HR= 1.43, 1.5 respectively). High SII had a negative impact on overall survival in Asian (p < 0.001) and Caucasian (p =0009) populations. Pooled HR results were also >1 in the subgroups of sample size and cutoff value, the differences between them were statistically significant (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the association between SII and OS.

Table 2.

Summary of the subgroup analysis between SII and OS

| Subgroup | No. study | HR | 95%CI | P | P for subgroup difference | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | Ph | ||||||

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||||

| Asian | 17 | 1.26 | 1.12 -1.40 | <0.001 | 81.4 | <0.001 | |

| Caucasian | 5 | 1.55 | 0.84-2.27 | 0.009 | 64.5 | 0.024 | |

| Cancer type | <0.001 | ||||||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 6 | 2.11 | 1.59-2.38 | <0.001 | 0 | 0.71 | |

| Gastric Cancer | 3 | 1.43 | 1.12-1.83 | 0.005 | 53.4 | 0.117 | |

| ESCC | 3 | 1.50 | 1.09-2.06 | 0.013 | 75.9 | 0.016 | |

| Urinary system cancer | 2 | 1.82 | 1.44-2.32 | <0.001 | 0 | 0.931 | |

| Other | 3 | 1.77 | 1.30-2.41 | <0.001 | 53.1 | 0.119 | |

| Biliary system cancer | 2 | 1.84 | 0.35-9.63 | 0.469 | 76.1 | 0.041 | |

| Colorectal cancer | 3 | 1.57 | 0.65-3.79 | 0.313 | 94 | <0.001 | |

| Sample size | <0.001 | ||||||

| Sample size≤255 | 11 | 1.14 | 0.89-1.39 | <0.001 | 34.4 | 0.123 | |

| Sample size>255 | 11 | 1.31 | 1.16-1.45 | <0.001 | 87.8 | <0.001 | |

| Cutoff value | <0.001 | ||||||

| ≤560 | 11 | 1.21 | 1.00-1.43 | <0.001 | 83.9 | <0.001 | |

| >560 | 11 | 1.32 | 1.14-1.51 | <0.001 | 61.7 | 0.004 | |

Abbreviations: ESCC: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; No: number; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

In addition, meta-regression was used to investigate the influence of different subgroups of SII on the prognosis of cancer and according to the results they did not significantly impact our merge HR. (pstudydesign=0.157, p cancer type=0.412, p Ethnicity=0.777, p cutoff =0.139, p sample size =0.513, p country= 0.572, pnos=0.528, pmodel=0.504).

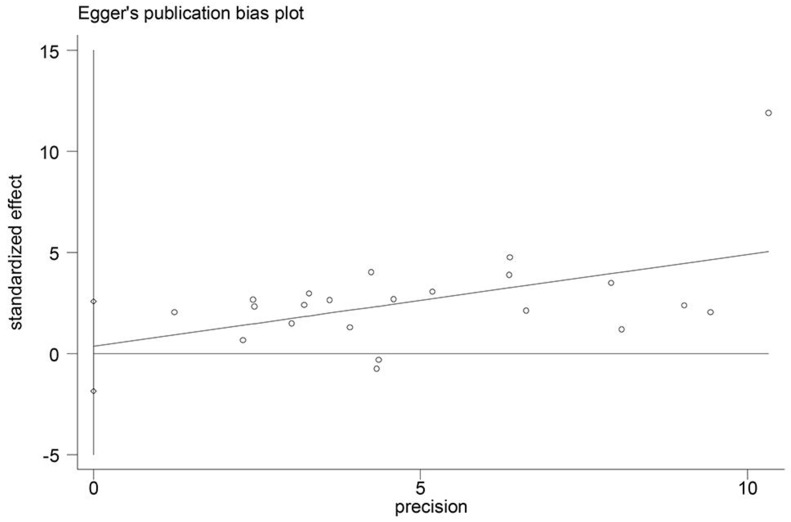

Publication bias

Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test were used to assess potential publication bias in this meta-analysis. The p values for OS were 0.114 (Begg's test) and 0.741 (Egger's test) and there was no publication bias. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Funnel plot for detecting publication bias.

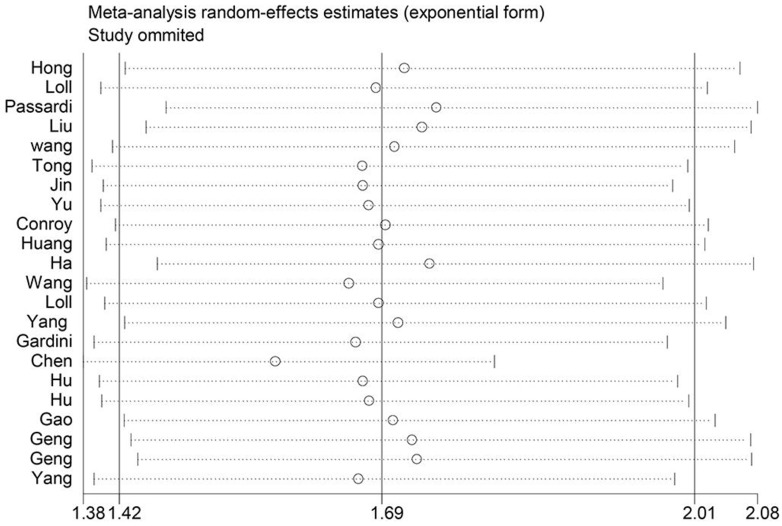

Sensitivity analyses

We performed leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to check if any study influenced the HR of OS. According to the senstivity analysis result, getting rid of any single literature did not significantly alter the pooled HR indicating that our analysis result was robustness. (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis on the relationship between SII and OS.

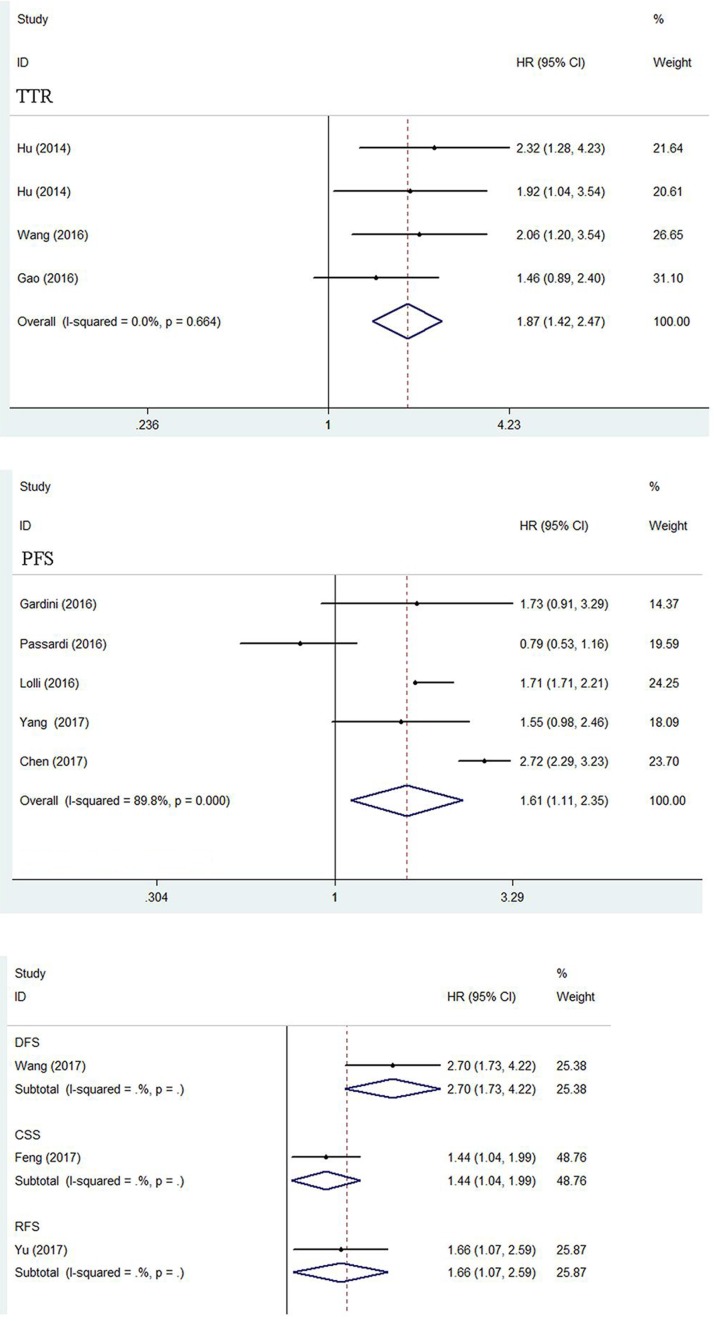

Time to recurrent

A total of three articles consisted of 602 patients reported HR for TTR. The heterogeneity test showed no obvious heterogeneity and a fixed-effect model was used (I2=0.0%, ph =0.664).The pooled HR was 1.87 (95%CI=1.42-2.47, p<0.001) revealing the significant relationship between high SII level and poor TTR in cancers. (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the association between SII and TTR, PFS, CSS, DFS and RFS.

Progress-free survival

Five articles comprising 1205 patients reported HR for PFS. The random-effect model was performed (I2=89.8%, ph=0.000). The combined result revealed that SII over the cutoff was related to the worse PFS outcome (HR=1.61, 95%CI=1.11-2.35, p=0.012). (Figure 5)

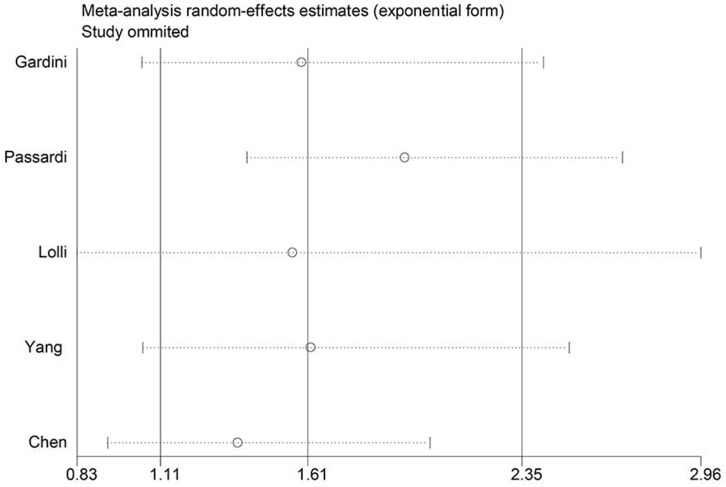

Because of high heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis was used to check the robustness of the result. As shown in Figure 6, any single study did not substantially influence the merged HRs when deleted from the whole study.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis on the relationship between SII and PFS.

Cancer-specific survival, Disease-free survival and Relapse-free survival

There were three articles separately reported HR for CSS, DFS and RFS. The merged HR was 1.44 (p=0.027), 2.70 (p<0.001) and 1.66 (p=0.025) respectively, indicating significant association between high SII and poor CSS DFS, and RFS in cancers. (Figure 5)

Discussion

The relationship between SII and prognosis in cancer patients is still contentious. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis including 22 articles and a total of 7657 patients to investigate the prognostic value of SII in cancer patients. Before this study, there was an article showed that high SII indicated a worse overall survival in all gastrointestinal tract cancers and was not associated with a hazard ratio for worse PFS outcome 29. However, in our meta-analysis, we come to a different conclusion. According to the result, High SII was associated with worse outcome of OS, TTR, PFS, CSS, DFS and RFS (HR=1.69, 1.87, 1.61, 1.44, 2.70 and 1.66 respectively). Subgroup analysis also indicated that SII over the cutoff value could predict worse OS in Hepatocellular carcinoma (p<0.001), Gastric cancer (p=0.005), Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (p=0.013), Urinary system cancer (p<0.001), Small cell lung cancer (p<0.001), Non-Small cell lung cancer (p<0.001) and Acral Melanoma (p<0.001), not colorectal cancer (p=0.313). The cutoff value of SII in these articles was not uniform, but the result of meta-regression analysis has shown that it did not influence our results. Nevertheless, we still need to adjust the optimal cutoff according to the clinical parameters in future clinical trials.

Inflammatory responses have been confirmed to play decisive roles at different stages of cancer development, including initiation, malignant conversion, promotion, tissue infiltration and metastasis 30. SII , a new inflammatory index, based on neutrophil, lymphocyte and platelet counts has been recently suggested to be associated with poor outcome of cancer, and it was also reported to have a significant correlation with the number of circulating tumor cells which greatly promote the metastatic of cancer31.

Several possible mechanisms can make explanation for the prognostic values of SII in cancer. Cancer patients often suffer from thromboembolic diseases17. And the causes of thrombocytosis may be that some tumor cells can produce and increase thrombopoietin (TPO), in addition, several platelet activation markers, such as P-selectin, β-thromboglobulin or CD40 ligand have been found to be up-regulated and contribute to the increase of platelet 32. Platelet-derived TGF-β not only down-regulates the cytokine NKG2D (Natural Killer Group 2, member D) on NK-cell surface to protect tumor cells from immune system surveillance but activates TGF-β/Smad to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) which contributes to the metastasis of cancer, and the direct interaction between cancer cells and platelets activates the NF-κb signaling, which in coordination with TGF-β signaling facilitates EMT and metastasis. Platelets are also able to mediate tumor cell survival and growth at distant sites by governing formation of metastatic niches 33-35. Recent years, lots of evidence have shown that neutrophils can promote tumor metastasis, neutrophil numbers, neutrophil-related factors, such as nitric oxide, arginase, IL-6 and functions have been associated with the progress of cancer27.In addition, platelets have been recognized to recruit and activate granulocytic cells in the tumor tissues, indicating that the platelet may be also essential for generation of tumor-associated neutrophils 36. Lymphocytes play significant roles in the balance between body defense and noxious agents involved in a number of diseases, including cancer. They induce cytotoxic cell death and inhibit tumor cell proliferation and migration, improve prognosis of cancer 37-38.

However, there are still some limitations in our meta-analysis. Firstly, the types of the cancers and their number were limited. Secondly, the studies included in our analysis mostly were retrospective studies and were published in English, which was more susceptible to potential biases. Thirdly, the cutoff value of SII was different in our analysis. Finally, there were some studies which did not focus on SII may be the sources of heterogeneity.

In summary, our meta-analysis reveals that high SII may be a reliable prognostic factor for worse OS of various cancers. However, given the limited number of studies included in the analysis, large-scale prospective and well-designed studies are also needed to be performed to confirm the conclusion in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary table.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Henan Natural Science Foundation (162300410288), National Natural Science Foundation (No. U1204811), China Postdoctoral Science special Foundation (2014T70688), and the Youth Innovation Fund of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (201301).

Author Contributions

Wanhai Wang proposed the study. Ruonan Yang and Nan Gao collected and analyzed the data. Ruonan Yang, Qian Chang and Xianchun Meng wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to this manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO: Fact sheet. World Health Organization. Accessed Feb 1 2017. Available from: http:// www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/

- 2.Ostan R, Lanzarini C, Pini E. et al. Inflammaging and Cancer: A Challenge for the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients. 2015;7:2589–2621. doi: 10.3390/nu7042589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang QT, Zhou L, Zeng WJ. et al. Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41:2411–2418. doi: 10.1159/000475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou WJ, Wu J, Li XD. et al. Effect of preoperative monocyte-lymphocyte ratio on prognosis of patients with resectable esophagogastric junction cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2017;39:178–183. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings M, Merone L, Keeble C. et al. Preoperative neutrophil:lymphocyte and platelet:lymphocyte ratios predict endometrial cancer survival. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:311–320. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Z, Zhou L, Gao S. et al. Prognostic Role of C-Reactive Protein in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:653–664. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu B, Yang XR, Xu Y. et al. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predicts Prognosis of Patients after Curative Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6212–6222. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geng Y, Shao Y, Zhu D. et al. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predicts Prognosis of Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Propensity Score-matched Analysis. SCI Rep-UK. 2016;6:39482. doi: 10.1038/srep39482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong X, Cui B, Wang M. et al. Systemic Immune-inflammation Index, Based on Platelet Counts and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio, Is Useful for Predicting Prognosis in Small Cell Lung Cancer. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2015;236:297–304. doi: 10.1620/tjem.236.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao X, Tian L, Wu J. et al. Circulating CD14+ HLA-DR-/low myeloid-derived suppressor cells predicted early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Hepatol Res. 2016;47:1061–1071. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Sun X, Liu J. et al. Preoperative C-Reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio Predicts Prognosis of Patients after Curative Resection for Gastric Cancer. TransL Oncol. 2015;8:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Z, Zhang J, Lu Y. et al. Aspartate aminotransferase-lymphocyte ratio index and systemic immune-inflammation index predict overall survival in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma patients after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Oncotarget. 2015;6:43090–43098. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casadei GA, Scarpi E, Faloppi L. et al. Immune inflammation indicators and implication for immune modulation strategies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving sorafenib. Oncotarget. 2016;7:67142–67149. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang BL, Tian L, Gao XH. et al. Dynamic change of the systemic immune inflammation index predicts the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Clin Chemlab Med. 2016;54:1963–196. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lolli C, Caffo O, Scarpi E. et al. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predicts the Clinical Outcome in Patients with mCRPC Treated with Abiraterone. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2016;7:376. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lolli C, Basso U, Derosa L. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts the clinical outcome in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer treated with sunitinib. Oncotarget. 2016;7:54564–54571. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang L, Liu S, Lei Y. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, thymidine phosphorylase and survival of localized gastric cancer patients after curative resection. Oncotarget. 2016;7:44185–44193. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha H, Nam AR, Bang JH. et al. Soluble programmed death-ligand 1 (sPDL1) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) predicts survival in advanced biliary tract cancer patients treated with palliative chemotherapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:76604–76612. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Passardi A, Scarpi E, Cavanna L. et al. Inflammatory indexes as predictors of prognosis and bevacizumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:33210–33219. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin H, Pang Q, Liu H. et al. Prognostic value of inflammation-based markers in patients with recurrent malignant obstructive jaundice treated by reimplantation of biliary metal stents. Medicine. 2017;96:e5895. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng J, Chen S, Yang X. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is a useful prognostic indicator for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Medicine. 2017;96:e5886. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong Y, Tan J, Zhou X. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicting chemoradiation resistance and poor outcome in patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl Med. 2017;15:221. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1326-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang K, Diao F, Ye Z, Prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with gastric cancer. Chin J Cancer; 2017. p. 12. 36:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Guo X, Wang M. et al. Pre-treatment inflammatory indexes as predictors of survival and cetuximab efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients with wild-type RAS. SCI Rep-UK. 2017;7:17166. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17130-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu J, Wu X, Yu H. et al. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index and Circulating T-Cell Immune Index Predict Outcomes in High-Risk Acral Melanoma Patients Treated with High-Dose Interferon. Transl Oncol. 2017;10:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conroy G, Salleron J, Belle A. et al. The prognostic value of inflammation-based scores in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients prior to treatment with sorafenib. Oncotarget. 2017;8:95853–95864. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, Wang C, Wang J. et al. A novel systemic immune-inflammation index predicts survival and quality of life of patients after curative resection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin. 2017;143:2077–86. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2451-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J, Zhai E, Yuan Y. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index for predicting prognosis of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroentero. 2017;23:6261. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong J H, Huang D H, Chen Z Y. Prognostic role of systemic immune-inflammation index in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:75381–8. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng L, Zou K, Yang C. et al. Inflammation-based indexes and clinicopathologic features are strong predictive values of preoperative circulating tumor cell detection in gastric cancer patients. Clinical and Translational Oncology. 2017;19:1125–1132. doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1649-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mammadova-Bach E, Mangin P, Lanza F. et al. Latelets in cancer. From basic research to therapeutic implications. Hamostaseologie. 2015;35:325–336. doi: 10.5482/hamo-14-11-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riedl J, Pabinger I, Ay C. Platelets in cancer and thrombosis. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:54–62. doi: 10.5482/HAMO-13-10-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mezouar S, Frere C, Darbousset R. et al. Role of platelets in cancer and cancer-associated thrombosis: Experimental and clinical evidences. Thromb Res. 2016;139:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swierczak A, Mouchemore KA, Hamilton JA. et al. Neutrophils: important contributors to tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Metast Rev. 2015;34:735–751. doi: 10.1007/s10555-015-9594-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J, Bae JS. Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Neutrophils in Tumor Microenvironment. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:6058147. doi: 10.1155/2016/6058147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer cell. 2011;20:576–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A. et al. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eurjepidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table.