Abstract

The role of iron as a critical nutrient in pathogenic bacteria is widely regarded as having driven selection for iron acquisition systems among uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) isolates. Carriage of multiple transition metal acquisition systems in UPEC suggests that the human urinary tract manipulates metal-ion availability in many ways to resist infection. For siderophore systems in particular, recent studies have identified new roles for siderophore copper binding as well as production of siderophore-like inhibitors of iron uptake by other, competing bacterial species. Among these is a process of nutritional passivation of metal ions, in which uropathogens access these vital nutrients while simultaneously protecting themselves from their toxic potential. Here, we review these new findings within the current understanding of UPEC transition metal acquisition.

Bacterial metal acquisition has long been understood to play an important role in infection pathogenesis. Historically, most studies in this area have focused on host–pathogen compettion for iron, a critical nutrient for most microbes. Recent studies have begun to consider how the full range of biologically relevant transition metals is handled at the host–microbe interface. In this review, we will consider host–bacteria metal interactions as they relate to human urinary tract infections (UTIs). We will focus primarily on lessons from Escherichia coli, the most common cause of complicated and uncomplicated UTIs. First, we will review recent findings on how human hosts manipulate metal availability during infection. Next, we will cover the many strategies used by uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) to control transition metal ions during colonization and infection. Prominent among these bacterial strategies have been small molecule chelators produced by the bacteria – siderophores and metallophores – with virulence-associated activities. While much remains unknown, a picture of myriad metal interactions in uropathogenesis extending well beyond iron alone is coming into focus.

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli

Urinary tract infections

UTIs are among the most commonly encountered infections in both outpatient and inpatient settings. While females are at greater lifetime risk for UTI, males exhibit a delayed, age-related increase in incidence. Oral antibiotics are the mainstay of UTI treatment and, in females without risk factors (‘uncomplicated UTI’), antibiotics are given for the purpose of minimizing symptoms. Urinary tract abnormalities, catheterization and diabetes (a few of the factors leading to designation as ‘complicated UTI’) increase both UTI risk and risk of progression to more severe infection. A minority of UTIs will progress to pyelonephritis (kidney infection) and even septicemia, sometimes due to anatomic abnormalities but often for unclear reasons. The dramatic expansion of antibiotic-resistant uropathogens is complicating UTI management, driving interest in new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Although a variety of uropathogens can cause UTI, E. coli is the most commonly isolated pathogen, with related Enterobacteriaceae such as Klebsiella, Enterobacter and Citrobacter comprising many of the remaining cases, particularly in hospital settings. Escherichia coli is thus the most widely studied uropathogen [1].

Escherichia coli UTI pathogenesis

The ascending infection model developed in the late 1970s by Thomas Stamey remains the dominant pathophysiological paradigm for UTI pathophysiology [2]. In females, the normal intestinal reservoir of colonizing E. coli first asymptomatically colonizes the vaginal mucosa. Next, urethral ascent to the bladder lumen results in detectable urinary bacteria (bacteriuria). This stage may either be asymptomatic, and not clinically regarded as an infection (asymptomatic bacteriuria), or symptomatic, meeting the clinical definition of bladder infection (cystitis). In a subset of these patients, E. coli ascends further to reach the kidneys, resulting in kidney infection (pyelonephritis), a more severe infection with potential to extend to the blood stream (septicemia). The ascending infection model thus requires infecting E. coli to successfully occupy and traverse a wide variety of host environments. In the intestine, oxygen can be low and E. coli generally exists with a diverse microbiome. Upon colonization of the vaginal mucosa, E. coli encounters a different microbiome, a different mucosal surface, and variable oxygenation levels. The luminal environment of the urinary tract consists of urine and a urine-exposed mucosal layer overlaying more specialized epithelial cell populations. The urinary component of these environments exhibits substantial compositional variation of ions, metabolites, proteins and cells. With tissue invasion, E. coli reaches interstitial spaces and even intracellular sites, where they occupy lysosome-like vesicles [3] or form biofilm-like intracellular bacterial communities (IBCs) in epithelial cells [4]. Resident and recruited phagocytic cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, create additional specialized microenvironments, such as phagolysosomes, likely to be relevant to UTI. While these environments are likely to exert substantial selective pressures on E. coli, we continue to learn more about their relevant features.

Virulence factors of UPEC

E. coli are genetically diverse, and urinary isolates tend to possess distinctive genetic features linked to virulence. Nearly 30% of open reading frames in E. coli UTI89, a model UPEC strain isolated from a patient with acute cystitis, are not found in strain MG1655, a derivative of the original K12 strain that was obtained from a fecal specimen in 1922 [5,6]. Urinary E. coli isolates from UTI patients similarly retain substantial genetic diversity, and their designation as UPEC is currently better regarded as a functional, rather than genetic, classification. Studies have linked both nonconserved genes (variable genes) and polymorphisms in conserved genes (core genes) to UPEC isolates. In studies of UPEC, nonconserved genes with putative disease-associated functions are generally designated as virulence factors (VFs), although microbiologists often use this term more broadly to describe any bacterial function that facilitates infection [7]. We will use the former definition in this review. VFs encompass a diverse range of functions ranging from enhancement of motility and adhesion, to toxin secretion and immune evasion, to nutrient acquisition (for review see [8]). Reliable monogenic VF associations with UTI are not observed, which may reflect individualistic selective pressures in each host, inaccuracies in clinically distinguishing asymptomatic bacteriuria from UTI, or a requirement for some VFs to exist within a larger synergistic group of VFs to manifest a phenotype. Indeed, when contemporary network approaches were used to discern VF combinations in 337 inpatient urinary E. coli isolates, stereotypical VF repertoires (mathematically termed as ‘communities’) were identified [9]. These communities were associated with patient sex and antibiotic resistance. One interpretation of these observations is that evolutionary pressures favor synergistic VF combinations, rather than individual VFs, that act as distinctive pathogenic ‘strategies’ during E. coli uropathogenesis. Interestingly, each VF community possessed a different siderophore system which indicated the presence of the other, co-associated VFs.

Additional evidence connecting transition metal interactions to clinical E. coli pathogenesis comes from transcriptional analysis of voided bacteria recovered from cystitis patients. These studies detected upregulation of multiple iron acquisition systems and a nickel uptake system in patients [10,11]. Transcriptional analysis of UTI89 within IBCs from a murine cystitis model further revealed that siderophore system genes are among the highest upregulated genes [12]. While a wide variety of bacterial factors are undoubtedly necessary for urinary virulence, multiple lines of genetic data support a closer look at the role of transition metal interactions in UPEC as a means to better understand how UPEC defeats the physiological barriers to UTI pathogenesis.

Bacterial demands for metals during infection

Metal ions are critical co-factors for around 40% of enzymes with known structures. Analysis of a representative subset of well-studied metalloenzymes suggests that metal cofactors directly catalyze redox chemistry for approximately a third of metalloenzymes [13]. Metals not involved with redox catalysis can still serve to activate a reactant, stabilize an intermediate or contribute to the overall protein structure [14]. Nutritional requirements for metal ions may change with the bacterial environment. Iron, in particular, is a classic growth-limiting nutrient of most free-living bacteria. Nickel is a critical cofactor for multiple anaerobic metabolism enzymes [15]. Adoption of aerobic respiration by facultative anaerobes, such as E. coli during movement from the gut to the urinary tract, will likely result in increased metal demands [16]. Redox enzymes are necessary both for electron transport chains during aerobiosis and for detoxification of reactive oxygen species. Biosynthesis of these metalloenzymes may be particularly consequential when UPEC encounters reactive oxygen species generated through the respiratory burst of phagocytic cells during active infections [17]. Transition metals such as Fe(III), Mn(II) and Cu(II) are necessary for the activity of superoxide dismutases (SODs), reductases, peroxidases and catalases [18]. In fact, manganese has been observed to help E. coli tolerate oxidative stress [19]. Manganese uptake is activated by H2O2 and it appears to protect against oxidative damage by activating Mn-SOD and metallating damaged iron-dependent enzymes [20]. The prominent role of metalloenzymes in tolerating infection-associated microenvironments suggests a particularly consequential role for microbial metal acquisition during infection pathogenesis.

Metal ion sources in the host

Host metal homeostasis

A substantial body of literature exists regarding iron homeostasis in humans, and this remains an active area of investigation. In reducing conditions such as anoxic environments, iron exists predominantly as reduced ferrous (Fe(II)) ions, which are relatively soluble. However, in oxic environments iron is oxidized, resulting in poorly soluble ferric (Fe(III)) ions, which form complexes of varying stability with most biomolecules. In human hosts, iron exists predominantly as ions complexed with heme or proteins, or in nonspecific complexes. The majority of heme molecules exist within intracellular protein complexes such as hemoglobin, myoglobin and cytochromes. The toxicity associated with free iron ions is largely controlled by the host through sequestration in proteins. A substantial fraction of nonheme iron is bound to intracellular ferritin, a 480 kDa protein which can bind up to 4500 Fe(III) ions [21]. Ferritin-bound iron is mobilized to the extracellular iron-binding protein transferrin, which can bind two ferric ions to form the predominant circulating form of iron. The degree of transferrin iron saturation is a commonly used metric of clinical iron status. The iron content of human urine is normally very low (∼0.1 μmol per liter) in the uninfected state [22]. Even in the absence of inflammatory stimuli, iron is subject to tight physiologic control.

Copper, zinc and nickel homeostasis are less well understood and the subject of active research. As with iron, these metals each have toxic potential and their free concentrations are subject to tight physiologic control. Ceruloplasmin is a cuproenzyme and the major form of circulating copper, accounting for >95% of plasma copper content [23]. Copper enters mammalian cells through members of the Ctr family of copper transporters and is subsequently delivered to cuproproteins via chaperones (Cox17, CCS, Atox1). ATP7A/B are P-type ATPases which serve to transport copper into vesicles or out of the cell, as needed [24]. Zinc is imported into mammalian cells via ZIP proteins of the SLC39 family [25] and is exported via Znt transport proteins of the SLC30 family. Znt proteins also facilitate loading of zinc into intracellular vesicles for utilization or storage [26,27]. Cytosolic copper and zinc can be bound by metallothioneins – a diverse class of proteins that may be involved in preventing metal toxicity, although their physiological functions are poorly understand and thought to be diverse [28]. The total transition metal content of human urine (per liter), is low, with urinary zinc content (∼4 μmoles) exceeding that of copper (∼0.2 μmoles), nickel (∼0.04 μmoles) and manganese (∼6 nmoles) [29]. Total urinary copper content increases during human and primate UTI, with ceruloplasmin accounting for a substantial portion of that increase [30,31].

Nutritional immunity

Nutritional immunity is a biological strategy in which the host restricts nutrient availability to microbes. Iron sequestration, a prototypical nutritional immune strategy, is accentuated in the host during infection. Systemic inflammation is associated with elevated circulating levels of hepcidin, a peptide hormone that induces a drop in serum iron content through intracellular sequestration and reduced dietary absorption [32]. Hepcidin knockout mice display symptoms of iron overload (hemochromatosis) and increased susceptibility to systemic infection by the siderophore-producing Gram-negative pathogen Vibrio vulnificus [33]. Metal ion transport can also act locally to control bacterial pathogens. The integral membrane protein NRAMP1 is localized to the phagolysosomal membrane, where it removes transition metals (iron and manganese) from the phagosome, denying these nutrients to engulfed bacteria [34]. Metal transport in these contexts is one important component of nutritional immunity.

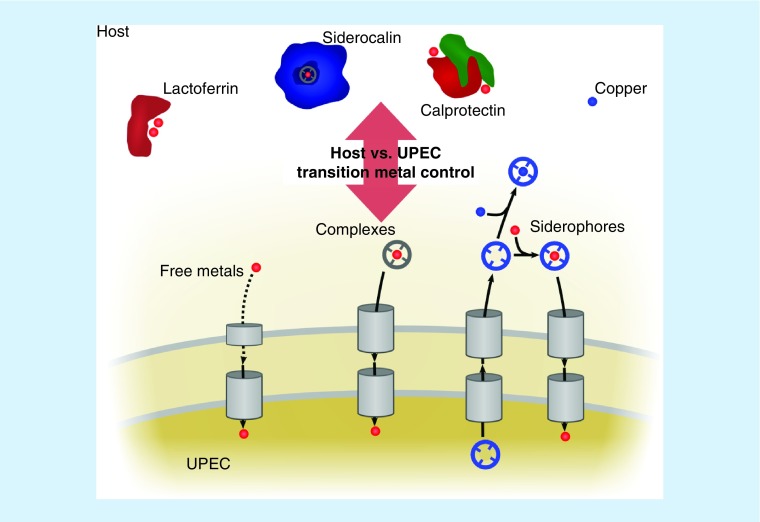

Inflammation brings numerous metal-binding proteins to the infected urinary tract. We define these metal-binding proteins as proteins with metal binding capacity that are secreted in their metal-free state in order to bind bioavailable metals at the site of inflammation, sequestering them from pathogens. Lactoferrin is a member of the transferrin family (61% sequence identity with transferrin) that is secreted by activated neutrophils and observed in urine from UTI patients [35]. Lactoferrin binds its two iron ions 300-times more tightly than transferrin [36]. The metal-binding protein complex calprotectin (a S100A8/S100A9 heterodimer) has also been associated with UTIs [37]. Initially appreciated to bind zinc and manganese [38], calprotectin has since been found to bind numerous transition metals, blocking bacterial access. A recent study found that extracellular Ca(II) allosterically stimulates binding of ferrous iron to calprotectin at a distinct site. This is unusual in that most iron sequestration proteins are known to sequester oxidized, ferric iron [39]. A similar activity was observed for Ni(II), starving Staphylococcus aureus of this metal [40]. Lactoferrin and calprotectin are thus examples of host proteins that may starve uropathogens of transition metals through direct metal ion binding.

Also increased in urine from UTI patients is siderocalin (SCN; also known as lipocalin-2/LCN2, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin/NGAL, or 24p3) [22,41], a soluble protein released by neutrophils and secreted by urinary epithelial cells in response to inflammatory stimuli [42,43]. SCN indirectly binds ferric ions through various small molecule chelators, motivating its renaming as SCN [44]. Urinary SCN levels are significantly higher in E. coli UTI patients than in asymptomatic controls [22,41]. In environments approximating human serum conditions, SCN can bind and sequester ferric complexes with enterobactin, the conserved E. coli siderophore [44,45]. However, in human urine with pH >6.5, SCN instead binds ferric ions through urinary catechol metabolites, forming a stable ferric–catechol complex. The ability of SCN to starve urinary E. coli of iron accordingly varies widely with the urinary catechol content [22,46]. The antibacterial mechanism of SCN may thus vary during infection or between individuals, depending upon urinary composition or tissue localization.

UPEC metal acquisition systems

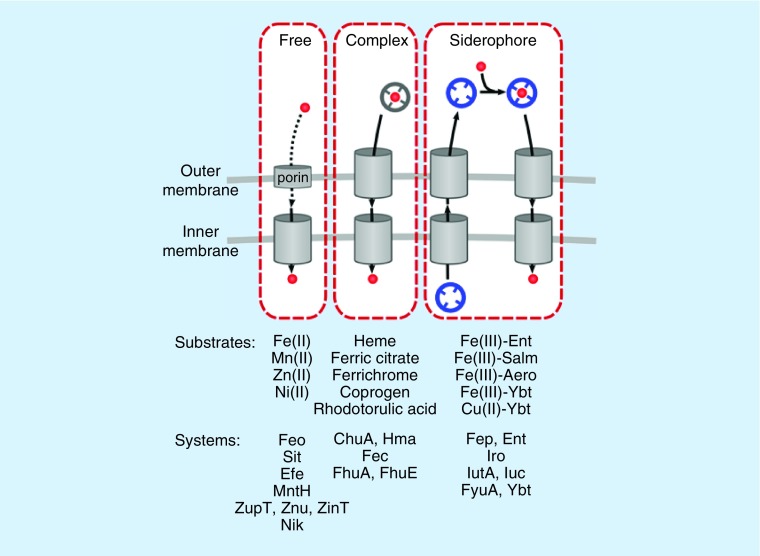

Competition for metal ions between host and pathogens appears to have driven substantial evolutionary adaptation by both E. coli and mammalian hosts. Metal scarcity is recognized in E. coli through conserved genetic systems, of which Fur (ferric uptake regulator) is best understood. Analogous transcriptional regulators, Zur, MntR and NikR, regulate zinc, manganese and nickel uptake, respectively [47–49]. These systems transcriptionally activate a variety of metal uptake genes in E. coli., can be functionally redundant, and are still being discovered. In this review, we classify metal import systems into three groups (Figure 1): import of uncomplexed free metal ions; import of metal ion complexes found in the host; and import of metal ions complexed with E. coli-produced chelators called siderophores. We will focus on those systems which have been directly tied to UPEC virulence, although novel putative metal acquisition systems are still being discovered in UPEC [50–52].

Figure 1. . Uropathogenic Escherichia coli metal acquisition strategies.

Three strategies of metal import are illustrated, with associated systems and transport substrates indicated below. Each system requires porins or dedicated outer membrane receptors as well as dedicated inner membrane transporters (cylinders) to transport either the bare metal (red sphere) or metal complexes (gray and blue complexes).

Import of free metal ions

If a metal ion is sufficiently soluble and abundant in a host infection environment, UPEC will utilize transporters dedicated to import of free (uncomplexed) ions. A number of these transporters have been associated with UTI pathogenesis. Metals transported in this way include ferrous iron, manganese, zinc and nickel. A number of metal ion transporters are capable of transporting multiple ions in vitro, which may obscure their physiological substrates or indicate a degree of functional redundancy. The majority of studies in this field have focused on the inner membrane transporters with the assumption that the metal ions are permeable to the outer membrane.

Reduced ferrous iron (Fe(II)) is more abundant in anoxic environments and is more soluble than oxidized ferric iron. Thus, in environments where ferrous iron is abundant, its direct import is plausible. At least five transporters in E. coli, FeoABC, SitABCD, MntH, EfeUOB and ZupT are capable of importing ferrous iron [53–58]. Of these, the Sit system specifically has been tied to UPEC virulence. Sit is present in two widely used UPEC model strains (UTI89 and CFT073), and its expression is enhanced during experimental murine cystitis [43,53]. Both SitABCD and MntH are also capable of manganese import [57,59,60], although their physiological substrates during UTI are unclear.

Nonferric divalent metal ion importers have also been implicated in animal models of E. coli UTI. The high affinity zinc importer, ZnuABC is important for in vitro UPEC growth in zinc-deficient conditions [61] and deletion mutants lacking znuABC exhibit diminished virulence [62]. The nickel import system, Nik, is upregulated in E. coli voided from female cystitis patients, and UPEC mutants lacking this system also exhibit a virulence defect [11].

Import of metal ion complexes in the host

Some metal ions interact with small molecules and form complexes that are soluble in the host, making these complexes nutritionally valuable to UPEC. UPEC systems that import these complexes stereotypically include an outer membrane receptor which imports the molecules into the periplasm using energy from the proton gradient across the inner membrane by coupling to the inner membrane TonB/ExbB/ExbD complex. Once in the periplasm, specific inner membrane transporters facilitate import or metal acquisition from these complexes.

Heme is the most abundant iron complex in the host, and heme receptors accordingly have a well-substantiated connection to UPEC. The Chu and Hma systems both import heme and are more prevalent in UPEC compared with commensal strains [63–66]. Transcriptional analysis of UPEC isolated from human infection reveals that chuA is highly upregulated, while hma was not as consistently or as highly upregulated [67]. chuA has been shown to be upregulated in murine UTI models [43,53]. An hma CFT073 mutant has decreased virulence in the kidneys in a murine co-infection model, and deletion of both receptors decreases kidney colonization [66]. Heme importers thus appear to play an important role in UPEC pathogenesis.

Other such UPEC systems with potential relevance to UTI are the Fec and Fhu systems. Fec imports ferric-citrate complexes, potentially taking advantage of the natural abundance of citrate in human urine and plasma, and its affinity for ferric ions [68–70]. The relevant substrate for Fhu during infection is less clear. Fhu genes (fhuABCDE) are capable of importing an array of ferric complexes, including the bacterial siderophore aerobactin and the fungal siderophores ferrichrome, coprogen, and rhodotorulic acid [71–73]. The fhuA gene emerged from an unbiased search for positively selected genes in UPEC [74], and fhuA and fhuC upregulation was observed in a murine UTI model [53]. Both FhuA and FhuE were detected on the cell surface of 44 and 11% of clinical UPEC isolates, respectively [50]. Whether the Fec and Fhu systems confer provirulence activities to UPEC remains unclear.

Siderophores

In addition to importing host metal complexes, UPEC also creates new metal complexes by synthesizing distinctive high-affinity small molecule metal chelators with higher metal ion affinities than many host proteins [75]. Bacterial chelators that bind ferric ions were among the first to be recognized. These were called siderophores which is Greek for ‘iron carrier’. Siderophores share an extraordinarily high affinity for ferric ions yet are chemically diverse. Following secretion by bacteria, they bind Fe(III) and the resulting complex is imported through dedicated import systems very similar to those described above for host metal ion complexes.

Enterobactin, the conserved E. coli siderophore

Enterobactin (formerly known as enterochelin) is a prototypical siderophore produced by all intestinal E. coli isolates studied to date [76]. Its biosynthesis and uptake genes are regarded as part of the core E. coli genome. Nevertheless, enterobactin production is not unique to E. coli and has also been described among urinary isolates of Klebsiella [77], Enterobacter and Citrobacter [78]. An even wider variety of bacteria, some of which are recovered from the urinary tract, are capable of using ferric enterobactin as an iron source despite their inability to synthesize this siderophore, a concept sometimes termed siderophore ‘piracy’ [79]. Enterobactin chelates ferric iron using three covalently linked 2,3-dihydroxybenzoylserine (DHBS) catechol moieties, affording an extremely high affinity for iron (Kd of 10-52 M) (Figure 2) [80].

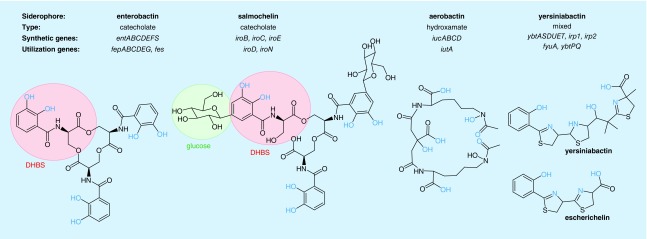

Figure 2. . Uropathogenic Escherichia coli siderophore systems.

The synthetic and utilization genes for each of the four uropathogenic Escherichia coli siderophore systems are indicated along with the type and structure of each siderophore. Chemical moieties involved in metal chelation are highlighted in orange. Distinctive chemical features are highlighted with colored circles.

DHBS: 2,3-dihydroxybenzoylserine.

Multiple lines of inquiry implicate the enterobactin system as a participant in human UTI pathogenesis. Enterobactin has been directly detected in urine from E. coli UTI patients [46], and mRNA for the outer membrane ferric enterobactin importer (fepA) was found to be upregulated in voided E. coli from UTI patients [10]. Two outer membrane receptors (Fiu and CirA) for the enterobactin subunits 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate and DHBS [81] (Figure 2) have also been observed to have increased transcription during human UTI, though their role in pathogenesis remains unclear [10]. A comparative genomic analysis of conserved genes in clinical E. coli isolates yielded evidence of positive selection in genes encoding components of both enterobactin biosynthesis (entD, entF) and uptake (fepE) among urinary strains [74]. Together these findings indicate that the enterobactin system is active during human UTI and influences E. coli fitness sufficiently to have influenced evolution of urinary strains.

The exceptional ferric ion affinity of enterobactin makes it capable of successfully competing with ferric ions bound to mammalian iron binding proteins that appear in the human urinary tract. In serum-like environments SCN can sequester ferric enterobactin using a bacterium's own siderophore to deprive it of iron [44,45]. In human urine, however, the SCN calyx instead uses urinary catechols to sequester iron. These catechols are host-derived urinary metabolites that exhibit marked individual differences in concentration. Enterobactin appears to be particularly capable of retrieving iron from these catechol–SCN complexes [22,46]. Because urinary conditions necessary for SCN to sequester iron–catechol complexes (pH >6.5 and the presence of specific unconjugated catechols) vary between human hosts, the virulence-associated gains of function conferred by the enterobactin system may be strongly host dependent. Indeed, Paragas et al. have described a urinary acidification response (pH <6.0) to UTI in mice that would be expected to interfere with catechol-mediated, but perhaps not enterobactin-mediated iron sequestration by SCN [41]. The literature thus supports scenarios in which the chemical composition of UTI microenvironments determines whether enterobactin facilitates bacterial access to iron (when SCN uses catechols to bind iron) or iron deprivation (when SCN sequesters ferric enterobactin).

Salmochelin, a virulence-associated enterobactin derivative

Salmochelin is the most recently identified UPEC siderophore and is a modified form of enterobactin generated by a distinctive C-glucosylation of the catechols and hydrolysis of the enterobactin cyclic trilactone scaffold (Figure 2) [82,83]. Originally identified from Salmonella species, it is also produced by UPEC carrying the nonconserved iroA gene cluster in the genome or plasmids [84]. This gene cluster does not encode the genes necessary for total synthesis of salmochelin, instead, its biosynthetic genes encode an enzyme that couples glucose to enterobactin through an unusual carbon linkage (iroB) [82] and a periplasmic esterase (iroE) that linearizes cyclic versions of enterobactin and salmochelin prior to secretion [85,86]. The iroA cluster also encodes a distinct exporter, receptor and cytoplasmic esterase (Figure 2) necessary for salmochelin-mediated iron uptake [82,85–87].

Evidence of salmochelin expression during clinical UTI is limited to transcriptional detection of the mRNA encoding the outer membrane salmochelin importer (iroN) in the voided E. coli recovered from some female UTI patients [67]. Transcriptional profiling of IBCs isolated by laser microdissection in a murine UTI model detected a 45–234-fold increase in iroA gene transcription compared with the same bacterial strain recovered from the intestine [43]. When concurrent urinary and rectal isolates from uncomplicated female outpatients were compared, urinary isolates produced more salmochelin in a standard culture condition than their corresponding rectal strains [76]. In another study of males with febrile UTI, E. coli carrying the salmochelin import gene iroN were more common among urinary than concurrent rectal isolates [88]. Metabolomic profiling suggests that the cost of producing salmochelin may be much higher than the cost of producing enterobactin or Ybt. The persistence of salmochelin production among clinical E. coli isolates suggests that the adaptive benefit of this system may exceed its metabolic cost in some environments [89].

Converting enterobactin to salmochelin generates a larger and more hydrophilic siderophore [82]. This may minimize membrane partitioning and binding to hydrophobic surfaces, increasing salmochelin's value to UPEC in the host [90,91]. The addition of two bulky C-linked glucoses to enterobactin, in particular, sterically prevents its sequestration by SCN, a virulence-associated property observed in culture and in a murine infection model. In these models, the iroA gene cluster rescues SCN-mediated growth restriction [92]. Beyond its canonical siderophore function, the salmochelin outer membrane receptor, IroN, has specifically been linked to biofilm formation and invasion of uroethelial cells by UPEC through unclear mechanisms [93,94]. In the animal models examined to date, modest defects for iroN-null UPEC strains have been observed [95,96]. It remains unclear exactly where and how salmochelin is most influential during UTI pathogenesis.

Aerobactin, a citrate-derived siderophore

Aerobactin is a hydroxamate-type siderophore originally isolated from Aerobacter aerogenes that is structurally distinct from enterobactin, salmochelin and Ybt (Figure 2) [97]. The operon containing synthetic (iucABCD) and outer membrane receptor (iutA) genes is present in the chromosome or virulence-associated plasmids of UPEC [7,98], as well as a wide variety of other medical and environmental bacterial species. Aerobactin-mediated iron uptake involves separate, conserved E. coli genes (fhuBCD) implicated in uptake of ferric hydroxamates [73]. Unlike enterobactin and salmochelin, it appears that the metal can be removed from aerobactin in a nondestructive manner and that the cell recycles the metal-free aerobactin [73]. Although aerobactin has a lower affinity for iron than enterobactin [99], its association with virulence raises the possibility that it confers important gains of function during infections.

Evidence of aerobactin expression during clinical UTIs is suggested by transcriptional detection of RNA for the associated outer membrane aerobactin importer (iutA) in some voided E. coli recovered from female UTI patients [67]. However, because some iutA+ isolates do not synthesize aerobactin, the transcriptional data are not definitive evidence of aerobactin system expression during UTI [76]. Epidemiological studies indicate that aerobactin gene carriage is more frequent in isolates from the bladder, kidney and blood, than in fecal isolates [100]. Other epidemiologic studies have observed that aerobactin prevalence is higher in UPEC strains which cause same-strain recurrent infections [101,102]. A recent large study of inpatient urinary isolates found that iucD was associated with both fluoroquinolone resistance and male patients [9]. Genes encoding the aerobactin system have been noted in several UTI-associated multidrug-resistant (including fluoroquinolone resistance) E. coli strains, including E. coli ST131 [103]. The nature of association between the aerobactin system and antibiotic resistance remains unclear.

Specific gains-of-function that may be conferred by aerobactin over other UPEC siderophores are incompletely understood. In mouse UTI competition assays, E. coli mutants deficient in aerobactin uptake (iutA–deficient CFT073) compete poorly in the bladder and kidney with isogenic wild-type strains with intact enterobactin and salmochelin systems [104,105]. Aerobactin is relatively uninhibited in the presence of serum, perhaps due to a lower hydrophobicity and lack of aromatic character relative to enterobactin [73]. One study indicates a superior ability to steal iron from transferrin in the presence of serum [106]. Like salmochelin, aerobactin is resistant to SCN sequestration, another potentially virulence-associated property [45]. Unlike salmochelin, ferric ion binding to aerobactin is relatively insensitive to low pH within the physiologic range [107], perhaps compensating for its lower affinity at neutral pH.

Yersiniabactin, an enterobacterial siderophore & metallophore

Yersiniabactin (Ybt), as the name suggests, was originally identified in Yersinia pestis (the agent of black plague). Ybt system genes are encoded in a complex, multioperon pathogenicity island known as the Yersinia high pathogenicity island (HPI) which has been identified in multiple urinary Enterobacteriaceae, including Klebsiella, Enterobacter and Citrobacter [108]. Expression of the HPI's four operons is dependent upon YbtA, an HPI-encoded transcription factor [109], with an additional level of transcriptional control by the ferric uptake repressor. Ybt is structurally distinct from enterobactin, salmochelin and aerobactin. An extensive nonribosomal peptide synthase/polyketide synthase system assembles salicylic acid, three cysteines and malonic acid to generate the polycyclic Ybt and the recently appreciated product escherichelin (Figure 2) [110,111]. Careful studies of the Ybt uptake pathway indicate that UPEC can completely recycle Ybt, nondestructively separating Ybt from its metal cargo and returning the liberated Ybt to the extracellular space, where it may undergo additional rounds of metal delivery [112].

Yersinia HPI activity in E. coli has been directly linked to human UTI pathogenesis. Both Ybt and escherichelin have been unambiguously detected using mass spectrometry in urine from E. coli UTI patients [111,113]. Transcriptional profiling of voided E. coli suggests that the outer membrane ferric Ybt importer (fyuA) is expressed during clinical UTI [67]. In IBCs isolated by laser microdissection in a murine UTI model, the first biosynthetic enzyme in Ybt biosynthesis (ybtS) was the most highly upregulated gene observed (∼2000-fold increase) when compared with expression in the same bacterial strain recovered from the intestine [43]. When concurrent urinary and rectal isolates from uncomplicated female outpatients were compared, more urinary isolates produced Ybt in a standard culture condition than concurrent rectal strains [76]. In another study of males with febrile UTI, E. coli carrying the Ybt import gene fyuA were more common among urinary than concurrent rectal isolates [88]. Interestingly, both biofilm production and the Yersinia HPI were found to be independently associated with UPEC strains which caused same-strain recurrent UTI [101]. Together, these data support an active role for the Yersinia HPI in clinical UTIs.

While a role for Ybt in the virulence of Yersinia pestis, where it appears to be the sole siderophore system, is well documented [108], evidence for its virulence-associated activity in UTI is more recent. A UPEC strain lacking the outer membrane importer FyuA was found to exhibit a virulence defect in an acute mouse UTI model (48 h infection of CBA/J mice) [10]. In a mouse cystitis model with a bimodal infection outcome (high titer vs low titer bladder infection after 1+ week infection of C3H/HEN or C3H/HeOuJ mice), a uropathogen lacking the Yersinia HPI-encoded inner membrane transporters, YbtP and YbtQ, exhibited a remarkable, 5–6 log-fold CFU defect relative to isogenic wild type in the mice that proceeded to high titer infections [114]. Interestingly, no defect was resolved in low titer infections where inflammation was low. This is a remarkable defect for nonessential, nonconserved genes and suggests that YbtP and YbtQ play important roles in virulence, despite the presence of intact enterobactin and salmochelin systems. In its canonical iron-scavenging role, Ybt's resistance to sequestration by SCN is one possible explanation for this activity [115], although Ybt appears to be ineffective at removing iron from SCN/catechol complexes [22]. These data suggest a consequential role for metal-Ybt import proteins during UTI.

Noncanonical functions of the UPEC Yersinia HPI

Yersiniabactin is a metallophore

Recent data point to additional roles for Ybt beyond siderophore-mediated iron acquisition that may explain why UPEC often carry the Yersinia HPI alongside other siderophore systems. Ybt was found to readily form stable complexes with copper during both human and experimental murine UTI [113]. In vitro biometal screens found that Ybt forms stable complexes with iron, copper, cobalt and nickel in vitro [116]. The Yersinia HPI-encoded outer membrane receptor, FyuA, recognized each of these non-iron Ybt complexes and could import them into E. coli [116]. Subsequent work has shown that Cu(II)-Ybt import supports the activity of E. coli amine oxidase (TynA), a classic copper-dependent enzyme, demonstrating that Cu(II)-Ybt can serve as a nutrient source for E. coli [112]. This nutritional role was dependent upon expression of the inner membrane ABC transporters, YbtP and YbtQ. The Yersinia HPI is thus a urovirulence-associated exception to the oft-stated premise that E. coli lacks a copper import system. Although a stable Zn(II) complex has not been observed [116], indirect data involving the Yersinia HPI-encoded inner membrane permease YbtX suggest a role in zinc import through an as yet unidentified mechanism [117,118]. Together these studies provide compelling evidence that Ybt should be regarded not only as a siderophore but as a metallophore, capable of facilitating import of multiple transition metal ions for nutritional purposes. As such, Ybt appears to not be entirely functionally redundant with the other UPEC siderophores, as it originally appeared.

Metal toxicity & nutritional passivation by yersiniabactin

Copper is a distinctive biological metal recognized as both a bacterial nutrient and toxin. While copper is a key cofactor for multiple E. coli enzymes, it can also generate reactive oxygen species and, as reduced Cu(I) ions, damage cytoplasmic iron–sulfur clusters [119]. Indeed, E. coli has long been appreciated to possess multiple genetic systems that protect from copper toxicity by exporting cytoplasmic copper ions [120]. Detection of Cu(II)–Ybt complexes in the urine from cystitis patients initially led to an investigation of the role of Ybt in the context of copper toxicity. Ybt was found to protect UPEC from copper toxicity by binding to the copper ions and minimizing their reactivity – a concept subsequently termed ‘passivation’ in a biological extension of the term from chemistry, which denotes a chemical interaction leading to decreased reactivity [112,121]. Urinary E. coli isolates were found to be more copper resistant than contemporaneous rectal isolates in UTI patients [113]. In voided E. coli from UTI patients, the copper efflux system, CusCFBA and CusRS, was observed to be upregulated [11], consistent with active copper stress during UTI. Taken together, these observations suggest that Ybt secretion protects UPEC from copper-mediated stress during UTI. These findings suggested a role for copper toxicity in human UTI.

Precisely where, and how, copper passivation by Ybt might influence UPEC pathogenesis remains unclear. Of note, copper supplementation and deprivation of mice have recently been shown to decrease and increase, respectively, bacterial colonization of the bladder [11,30]. These observations may relate to general changes in labile or ‘free’ copper in the proximity of infecting bacteria. Trafficking of the copper ion transporter ATP7A to phagolysosomes of macrophages implicates labile copper ions in phagocytic killing of E. coli. [122]. Consistent with a role for copper in phagolysosomal killing, Ybt-expressing UPEC exhibited a marked intracellular survival benefit following phagocytosis by macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells [113,123]. While the protective effect of Ybt may be attributable to copper passivation, Cu(II)-Ybt was also observed to act as a superoxide dismutation catalyst, analogous to SOD, a remarkable activity for a nonprotein biomolecule. Given the importance of SOD to intracellular survival in pathogenic bacteria, this may be an additional virulence-associated activity connected to Ybt production in UPEC.

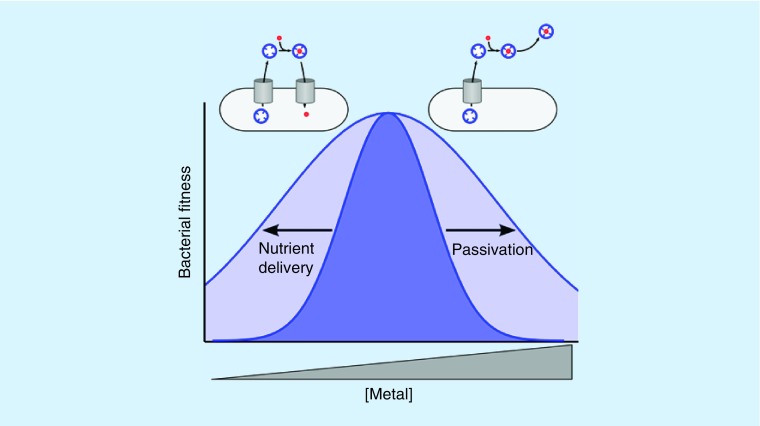

While Ybt-mediated copper uptake and passivation are seemingly contradictory functions, their co-existence may be an ingenious solution to a challenging biological problem. UPEC will secrete Ybt in molar excess of available copper, which could result in self-induced copper starvation. By permitting controlled Cu(II)-Ybt import, copper starvation is avoided. In the absence of copper toxicity, Ybt can act as a copper scavenger (a chalkophore) similarly to a siderophore. This dual functionality of Ybt Cu(II) binding activity has been termed nutritional passivation: a strategy of minimizing a metal ion's toxicity while preserving its nutritional availability (Figure 3) [112]. This flexibility of function may help UPEC adapt to multiple environments in the human urinary tract.

Figure 3. . Nutritional passivation by a metallophore.

A Gaussian curve (dark blue) represents bacterial fitness over a range of copper ion concentrations. Yersiniabactin–metal binding widens the curve in both directions (light blue) by passivating copper ions at higher concentrations and retaining nutritional access to trace copper at lower concentrations.

Escherichelin as an inhibitor of Pseudomonas siderophore-mediated iron uptake

A recent study found that Ybt is not the only specialized metabolite connected to the Yersinia HPI in UPEC [111]. A mass spectrometry-based metabolomic screen identified a prominent metabolite called escherichelin (Figure 2) as the product of a branch of the Ybt biosynthetic pathway. This specialized metabolite lacks the siderophore activity of Ybt, though it is capable of binding Fe(III). Surprisingly, escherichelin's structure matches that of a synthetic Pseudomonas antivirulence compound described by Mislin et al. in 2004 [124]. Escherichelin inhibits iron uptake by pyochelin, the structurally related, virulence-associated siderophore of Pseudomonas and related species. Inhibition appears to occur when escherichelin forms a nontransportable ferric complex with pyochelin in the binding pocket of the outer membrane receptor FptA [125]. As such, escherichelin may promote niche dominance during UTI pathogenesis, creating a less hospitable environment for Pseudomonas and other strains that use the pyochelin siderophore system. Although the pyochelin and Ybt biosynthetic pathways both generate the same escherichelin precursor, escherichelin production is greatly suppressed in Pseudomonas relative to UPEC, consistent with the expected species-specific selective pressure.

Production of an inhibitor of Pseudomonas virulence by urinary E. coli strains suggests a mechanistic reason for the positive association between antibiotic exposure (which would tend to suppress Ybt-producing Enterobacteriaceae) and UTI caused by relatively antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas species [126]. Indeed, therapeutic bladder colonization with an asymptomatic bacteriuria E. coli strain HU2117 [127] (a papG adhesion-null derivative of E. coli 83972) has been proposed to prevent Pseudomonas and other opportunistic infections. Mass spectrometric analysis of patients experimentally inoculated with HU2117 found abundant urinary escherichelin in successfully colonized patients [111]. These findings again expand the possible repertoire of siderophore system activities to include effectors of interspecies antagonism.

Conclusion

Together, these recent findings point to complex, nuanced mechanisms for both host and pathogen metal interactions. Metal ions are both nutritionally essential and potentially toxic to bacteria, resulting in sophisticated regulatory mechanisms in both host and pathogen. In fact, a number of UPEC virulence factors are involved in metal interactions – pointing to the critical importance of metal regulation during infection. Although originally regarded solely as part of a redundant iron acquisition system, recent findings support a distinctive and nonredundant metallophore function for Ybt. Mathematical analysis of the genetic distribution of virulence factors in UPEC indicates distinct communities of virulence factors, suggesting a variety of survival strategies. A parallel theme is observed when the complexity of UPEC metal interaction systems is considered in mechanistic detail – a range of mechanisms exist, each with unique benefits that are likely favorable under specific conditions. Within the diversity of microenvironments relevant to UTI pathogenesis, uropathogens likely benefit by drawing upon a repertoire of metal-interacting functions.

Future perspective

Mechanistic studies of bacterial metal uptake and resistance will continue to provide new insights into human–microbe interactions. These insights, in turn, will also suggest new anti-infective strategies based upon pharmaceutical agents, nutritional supplementation or probiotics. Progress in this area will be aided with an improved appreciation for which UPEC functions are redundant and which confer unique, virulence-associated properties. The answers to these questions may depend upon the specific combination of genes and polymorphisms present in a given UPEC isolate. A combination of functional and genomic studies may provide answers to these questions. The prospect of therapeutically manipulating the role of copper in UTI pathophysiology would benefit from a more extensive understanding of mammalian copper homeostasis. We anticipate that additional examples of nutritional passivation will be identified in non-UPEC bacteria. Lastly, the means by which some bacteria interfere with transition metal acquisition by different bacterial species may be harnessed or mimicked in future probiotic or pharmacologic therapies [128].

Executive summary.

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli

Antibiotic resistance and post-antibiotic recurrence challenge current treatment approaches.

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) virulence factors are distributed in statistically linked groupings, each with a representative siderophore system.

Siderophore expression is associated with UPEC isolates.

Metal ion control in the host

Hosts control the location and complexed form of biological metal ions through systemic and local responses.

These regulatory processes are enhanced during inflammation in a process termed nutritional immunity which results in the appearance of multiple iron sequestration proteins in the urinary tract during infection.

Siderocalin (Lipocalin-2) sequesters iron either by binding ferric enterobactin or, in the urinary environment, by binding a ferric complex involving urinary catechol metabolites; in the latter case, the iron remains accessible to siderophores.

UPEC metal acquisition systems

Overlapping systems in UPEC import metals as free ions, host-derived complexes and UPEC-derived siderophore complexes.

Direct mass spectrometric detection in clinical specimens demonstrates UPEC siderophore production during urinary tract infection.

The siderophore enterobactin liberates iron from siderocalin complexes during growth in human urine.

Noncanonical functions of the UPEC Yersinia high pathogenicity island

UPEC uses yersiniabactin as a metallophore to bind, and mediate import of, both iron and non-iron metal ions.

Yersiniabactin counteracts copper ion toxicity.

The microbial strategy of minimizing a metal ion's toxicity while preserving its nutritional availability has been termed nutritional passivation.

Escherichelin, a newly appreciated siderophore-like Yersinia high pathogenicity island product, is produced during clinical E. coli bacteriuria and inhibits siderophore-dependent Pseudomonas growth.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from NIH grants RO1 DK099534 and RO1 DK111930 as well as a Mr. and Mrs. Spencer T. Olin Fellowship for Women in Graduate Study to AER. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Gupta K, Grigoryan L, Trautner B. Urinary tract infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017;167(7):ITC49–ITC64. doi: 10.7326/AITC201710030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamey TA. Recurrent urinary tract infections in female patients: an overview of management and treatment [with panel discussion] Rev. Infect. Dis. 1987;9:S195–S210. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.supplement_2.s195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mysorekar IU, Hultgren SJ. Mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli persistence and eradication from the urinary tract. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(38):14170–14175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen DA, Hooton TM, Stamm WE, Humphrey PA, Hultgren SJ. Detection of intracellular bacterial communities in human urinary tract infection. PLoS Med. 2007;4(12):e329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caspi R, Altman T, Dreher K, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D742–D753. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachmann BJ. Pedigrees of some mutant strains of Escherichia coli K-12. Bacteriol. Rev. 1972;36(4):525–557. doi: 10.1128/br.36.4.525-557.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson JR, Moseley SL, Roberts PL, Stamm WE. Aerobactin and other virulence factor genes among strains of Escherichia coli causing urosepsis: association with patient characteristics. Infect. Immun. 1988;56(2):405–412. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.405-412.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson JR, Russo TA. Molecular epidemiology of extraintestinal pathogenic (uropathogenic) Escherichia coli . Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005;295(6):383–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker KS, Wilson JD, Marschall J, Mucha PJ, Henderson JP. Network analysis reveals sex- and antibiotic resistance-associated antivirulence targets in clinical uropathogens. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015;1(11):523–532. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Uses contemporary network analyses to identify common virulence factor combinations in Escherichia coli from a large clinical cohort. Siderophore system combinations were representative of the resulting groups.

- 10.Brumbaugh AR, Smith SN, Subashchandrabose S, et al. Blocking yersiniabactin import attenuates extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in cystitis and pyelonephritis and represents a novel target to prevent urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 2015;83(4):1443–1450. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02904-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subashchandrabose S, Hazen TH, Brumbaugh AR, et al. Host-specific induction of Escherichia coli fitness genes during human urinary tract infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111(51):18327–18332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415959112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conover MS, Hadjifrangiskou M, Palermo JJ, Hibbing ME, Dodson KW, Hultgren SJ. Metabolic requirements of Escherichia coli in intracellular bacterial communities during urinary tract infection pathogenesis. mBio. 2016;7(2):e00104–e00116. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00104-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreini C, Bertini I, Cavallaro G, Holliday GL, Thornton JM. Metal ions in biological catalysis: from enzyme databases to general principles. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13(8):1205–1218. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg JM. Metal ions in proteins: structural and functional roles. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1987;52:579–585. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballantine SP, Boxer DH. Nickel-containing hydrogenase isoenzymes from anaerobically grown Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1985;163(2):454–459. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.454-459.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alteri CJ, Smith SN, Mobley HLT. Fitness of Escherichia coli during urinary tract infection requires gluconeogenesis and the TCA cycle. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(5):e1000448. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ, Hampton MB. Reactive oxygen species and neutrophil function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016;85(1):765–792. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imlay JA. Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77(1):755–776. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.161055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anjem A, Imlay JA. Mononuclear iron enzymes are primary targets of hydrogen peroxide stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(19):15544–15556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.330365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anjem A, Varghese S, Imlay JA. Manganese import is a key element of the OxyR response to hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli . Mol. Microbiol. 2009;72(4):844–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothen A. Ferritin and apoferritin in the ultracentrifuge: studies on the relationship of ferritin and apoferritin; precision measurements of the rates of sedimentation of apoferritin. J. Biol. Chem. 1944;152(3):679–693. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shields-Cutler RR, Crowley JR, Hung CS, et al. Human urinary composition controls antibacterial activity of siderocalin. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290(26):15949–15960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.645812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Identifies a new mechanism of nutritional immunity in the presence of human urine that is counteracted by uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) siderophore expression.

- 23.Hellman NE, Gitlin JD. Ceruloplasmin metabolism and function. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002;22(1):439–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.012502.114457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puig S, Thiele DJ. Molecular mechanisms of copper uptake and distribution. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2002;6(2):171–180. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeong J, Eide DJ. The SLC39 family of zinc transporters. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013;34(2–3):612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmiter RD, Huang L. Efflux and compartmentalization of zinc by members of the SLC30 family of solute carriers. Pflügers Arch. 2004;447(5):744–751. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wellenreuther G, Cianci M, Tucoulou R, Meyer-Klaucke W, Haase H. The ligand environment of zinc stored in vesicles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;380(1):198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmiter RD. The elusive function of metallothioneins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95(15):8428–8430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieniawska CE, Jung LC, Olufadi R, Walker V. Twenty-four hour urinary trace element excretion: reference intervals and interpretive issues. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2012;49(4):341–351. doi: 10.1258/acb.2011.011179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyre AN, Kavanagh K, Kock ND, Donati GL, Subashchandrabose S. Copper is a host effector mobilized to urine during urinary tract infection to impair bacterial colonization. Infect. Immun. 2017;85(3) doi: 10.1128/IAI.01041-16. pii: e01041–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer-Siegler KL, Iczkowski KA, Vera PL. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is increased in the urine of patients with urinary tract infection: macrophage migration inhibitory factor–protein complexes in human urine. J. Urol. 2006;175(4):1523–1528. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00650-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganz T. Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron metabolism and mediator of anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2003;102(3):783–788. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arezes J, Jung G, Gabayan V, et al. Hepcidin-induced hypoferremia is a critical host defense mechanism against the siderophilic bacterium Vibrio vulnificus . Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wessling-Resnick M. Nramp1 and other transporters involved in metal withholding during infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290(31):18984–18990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.643973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan Y, Sonn GA, Sin MLY, et al. Electrochemical immunosensor detection of urinary lactoferrin in clinical samples for urinary tract infection diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010;26(2):649–654. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wally J, Buchanan SK. A structural comparison of human serum transferrin and human lactoferrin. Biometals. 2007;20(3):249. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reyes L, Alvarez S, Allam A, Reinhard M, Brown MB. Complicated urinary tract infection is associated with uroepithelial expression of proinflammatory protein S100A8. Infect. Immun. 2009;77(10):4265–4274. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00458-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corbin BD, Seeley EH, Raab A, et al. Metal chelation and inhibition of bacterial growth in tissue abscesses. Science. 2008;319(5865):962–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1152449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakashige TG, Zhang B, Krebs C, Nolan EM. Human calprotectin is an iron-sequestering host-defense protein. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015;11(10):765–771. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakashige TG, Zygiel EM, Drennan CL, Nolan EM. Nickel sequestration by the host-defense protein human calprotectin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139(26):8828–8836. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paragas N, Kulkarni R, Werth M, et al. α-Intercalated cells defend the urinary system from bacterial infection. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124(7):2963–2976. doi: 10.1172/JCI71630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Correnti C, Strong RK. Mammalian siderophores, siderophore-binding lipocalins, and the labile iron pool. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(17):13524–13531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.311829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reigstad CS, Hultgren SJ, Gordon JI. Functional genomic studies of uropathogenic Escherichia coli and host urothelial cells when intracellular bacterial communities are assembled. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(29):21259–21267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goetz DH, Holmes MA, Borregaard N, Bluhm ME, Raymond KN, Strong RK. The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol. Cell. 2002;10(5):1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;432(7019):917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shields-Cutler RR, Crowley JR, Miller CD, Stapleton AE, Cui W, Henderson JP. Human metabolome-derived cofactors are required for the antibacterial activity of siderocalin in urine. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291(50):25901–25910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.759183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Demonstrates enterobactin production by UPEC in the presence of siderocalin during clinical urinary tract infection. Urinary metabolites are identified that are used by siderocalin to sequester ferric ions.

- 47.Gilston BA, Wang S, Marcus MD, et al. Structural and mechanistic basis of zinc regulation across the E. coli Zur regulon. PLoS Biol. 2014;12(11):e1001987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chivers PT, Sauer RT. NikR repressor: high-affinity nickel binding to the C-terminal domain regulates binding to operator DNA. Chem. Biol. 2002;9(10):1141–1148. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waters LS, Sandoval M, Storz G. The Escherichia coli MntR miniregulon includes genes encoding a small protein and an efflux pump required for manganese homeostasis. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193(21):5887–5897. doi: 10.1128/JB.05872-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wurpel DJ, Moriel DG, Totsika M, Easton DM, Schembri MA. Comparative analysis of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli surface proteome by tandem mass-spectrometry of artificially induced outer membrane vesicles. J. Proteomics. 2015;115(C):93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russo TA, Carlino UB, Johnson JR. Identification of a new iron-regulated virulence gene, ireA, in an extraintestinal pathogenic isolate of Escherichia coli . Infect. Immun. 2001;69(10):6209–6216. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6209-6216.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ouyang Z, Isaacson R. Identification and characterization of a novel ABC iron transport system, Fit, in Escherichia coli . Infect. Immun. 2006;74(12):6949–6956. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00866-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Snyder JA, Haugen BJ, Buckles EL, et al. Transcriptome of uropathogenic Escherichia coli during urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 2004;72(11):6373–6381. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6373-6381.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kammler M, Schön C, Hantke K. Characterization of the ferrous iron uptake system of Escherichia coli . J. Bacteriol. 1993;175(19):6212–6219. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6212-6219.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hantke K. Is the bacterial ferrous iron transporter FeoB a living fossil? Trends Microbiol. 2003;11(5):192–195. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cao J, Woodhall MR, Alvarez J, Cartron ML, Andrews SC. EfeUOB (YcdNOB) is a tripartite, acid-induced and CpxAR-regulated, low-pH Fe2+ transporter that is cryptic in Escherichia coli K-12 but functional in E. coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65(4):857–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Makui H, Roig E, Cole ST, Helmann JD, Gros P, Cellier MFM. Identification of the Escherichia coli K-12 Nramp orthologue (MntH) as a selective divalent metal ion transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35(5):1065–1078. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grass G, Franke S, Taudte N, et al. The metal permease ZupT from Escherichia coli is a transporter with a broad substrate spectrum. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187(5):1604–1611. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1604-1611.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sabri M, Léveillé S, Dozois CM. A SitABCD homologue from an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain mediates transport of iron and manganese and resistance to hydrogen peroxide. Microbiology. 2006;152(3):745–758. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kehres DG, Janakiraman A, Slauch JM, Maguire ME. SitABCD is the alkaline Mn2+ transporter of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184(12):3159–3166. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.12.3159-3166.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gunasekera TS, Herre AH, Crowder MW. Absence of ZnuABC-mediated zinc uptake affects virulence-associated phenotypes of uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073 under Zn(II)-depleted conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009;300(1):36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sabri M, Houle S, Dozois CM. Roles of the extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli ZnuACB and ZupT zinc transporters during urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 2009;77(3):1155–1164. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01082-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wyckoff EE, Duncan D, Torres AG, Mills M, Maase K, Payne SM. Structure of the Shigella dysenteriae haem transport locus and its phylogenetic distribution in enteric bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;28(6):1139–1152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagy G, Dobrindt U, Kupfer M, Emody L, Karch H, Hacker J. Expression of hemin receptor molecule ChuA is influenced by RfaH in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain 536. Infect. Immun. 2001;69(3):1924–1928. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1924-1928.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hagan EC, Mobley HLT. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli outer membrane antigens expressed during urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 2007;75(8):3941–3949. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00337-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hagan EC, Mobley HLT. Haem acquisition is facilitated by a novel receptor Hma and required by uropathogenic Escherichia coli for kidney infection. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;71(1):79–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hagan EC, Lloyd AL, Rasko DA, Faerber GJ, Mobley HLT. Escherichia coli global gene expression in urine from women with urinary tract infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(11):e1001187. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Detects transcriptional activation of siderophore systems in E. coli directly recovered from UTI patients.

- 68.Wagegg W, Braun V. Ferric citrate transport in Escherichia coli requires outer membrane receptor protein fecA. J. Bacteriol. 1981;145(1):156–163. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.156-163.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pressler U, Staudenmaier H, Zimmermann L, Braun V. Genetics of the iron dicitrate transport system of Escherichia coli . J. Bacteriol. 1988;170(6):2716–2724. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2716-2724.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Staudenmaier H, Van Hove B, Yaraghi Z, Braun V. Nucleotide sequences of the fecBCDE genes and locations of the proteins suggest a periplasmic-binding-protein-dependent transport mechanism for iron(III) dicitrate in Escherichia coli . J. Bacteriol. 1989;171(5):2626–2633. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2626-2633.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kadner RJ, Heller K, Coulton JW, Braun V. Genetic control of hydroxamate-mediated iron uptake in Escherichia coli . J. Bacteriol. 1980;143(1):256–264. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.1.256-264.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hantke K. Identification of an iron uptake system specific for coprogen and rhodotorulic acid in Escherichia coli K12. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1983;191(2):301–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00334830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Braun V, Brazel-Faisst C, Schneider R. Growth stimulation of Escherichia coli in serum by iron(III) aerobactin. Recycling of aerobactin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1984;21(1):99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen SL, Hung C-S, Xu J, et al. Identification of genes subject to positive selection in uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli: a comparative genomics approach. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(15):5977–5982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Neilands JB. Siderophores: structure and function of microbial iron transport compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270(45):26723–26726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Henderson JP, Crowley JR, Pinkner JS, et al. Quantitative metabolomics reveals an epigenetic blueprint for iron acquisition in uropathogenic Escherichia coli . PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(2):e1000305. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Podschun R, Sievers D, Fischer A, Ullmann U. Serotypes, hemagglutinins, siderophore synthesis, and serum resistance of Klebsiella isolates causing human urinary tract infections. J. Infect. Dis. 1993;168(6):1415–1421. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mokracka J, Koczura R, Kaznowski A. Yersiniabactin and other siderophores produced by clinical isolates of Enterobacter spp. and Citrobacter spp. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2004;40(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rutz JM, Abdullah T, Singh SP, Kalve VI, Klebba PE. Evolution of the ferric enterobactin receptor in Gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173(19):5964–5974. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.5964-5974.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cooper SR, McArdle JV, Raymond KN. Siderophore electrochemistry: relation to intracellular iron release mechanism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1978;75(8):3551–3554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hantke K. Dihydroxybenzolyserine – a siderophore for E. coli . FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990;67(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90158-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hantke K, Nicholson G, Rabsch W, Winkelmann G. Salmochelins, siderophores of Salmonella enterica and uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains, are recognized by the outer membrane receptor IroN. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(7):3677–3682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737682100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bister B, Bischoff D, Nicholson GJ, et al. The structure of salmochelins: C-glucosylated enterobactins of Salmonella enterica . Biometals. 2004;17(4):471–481. doi: 10.1023/b:biom.0000029432.69418.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Johnson JR, Russo TA, Tarr PI, et al. Molecular epidemiological and phylogenetic associations of two novel putative virulence genes, iha and iroN(E. coli), among Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urosepsis. Infect. Immun. 2000;68(5):3040–3047. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.3040-3047.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lin H, Fischbach MA, Liu DR, Walsh CT. In vitro characterization of salmochelin and enterobactin trilactone hydrolases IroD, IroE, and Fes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127(31):11075–11084. doi: 10.1021/ja0522027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhu M, Valdebenito M, Winkelmann G, Hantke K. Functions of the siderophore esterases IroD and IroE in iron-salmochelin utilization. Microbiology. 2005;151(7):2363–2372. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crouch M-LV, Castor M, Karlinsey JE, Kalhorn T, Fang FC. Biosynthesis and IroC-dependent export of the siderophore salmochelin are essential for virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;67(5):971–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johnson JR, Scheutz F, Ulleryd P, Kuskowski MA, O'Bryan TT, Sandberg T. Phylogenetic and pathotypic comparison of concurrent urine and rectal Escherichia coli isolates from men with febrile urinary tract infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43(8):3895–3900. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3895-3900.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lv H, Hung CS, Henderson JP. Metabolomic analysis of siderophore cheater mutants reveals metabolic costs of expression in uropathogenic Escherichia coli . J. Proteome Res. 2014;13(3):1397–1404. doi: 10.1021/pr4009749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Konopka K, Neilands JB. Effect of serum albumin on siderophore-mediated utilization of transferrin iron. Biochemistry. 1984;23(10):2122–2127. doi: 10.1021/bi00305a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Luo M, Lin H, Fischbach MA, Liu DR, Walsh CT, Groves JT. Enzymatic tailoring of enterobactin alters membrane partitioning and iron acquisition. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006;1(1):29–32. doi: 10.1021/cb0500034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fischbach MA, Lin H, Zhou L, et al. The pathogen-associated iroA gene cluster mediates bacterial evasion of lipocalin 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(44):16502–16507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604636103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Magistro G, Hoffmann C, Schubert S. The salmochelin receptor IroN itself, but not salmochelin-mediated iron uptake promotes biofilm formation in extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015;305(4–5):435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Feldmann F, Sorsa LJ, Hildinger K, Schubert S. The salmochelin siderophore receptor IroN contributes to invasion of urothelial cells by extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in vitro . Infect. Immun. 2007;75(6):3183–3187. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00656-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Russo TA, McFadden CD, Carlino-MacDonald UB, Beanan JM, Barnard TJ, Johnson JR. IroN functions as a siderophore receptor and is a urovirulence factor in an extraintestinal pathogenic isolate of Escherichia coli . Infect. Immun. 2002;70(12):7156–7160. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.7156-7160.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Steigedal M, Marstad A, Haug M, et al. Lipocalin 2 imparts selective pressure on bacterial growth in the bladder and is elevated in women with urinary tract infection. J. Immunol. 2014;193(12):6081–6089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gibson F, Magrath DI. The isolation and characterization of a hydroxamic acid (aerobactin) formed by Aerobacter aerogenes 62–1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1969;192(2):175–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(69)90353-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schmidt H, Hensel M. Pathogenicity islands in bacterial pathogenesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004;17(1):14–56. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.14-56.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Harris WR, Carrano CJ, Raymond KN. Coordination chemistry of microbial iron transport compounds. 16. Isolation, characterization, and formation constants of ferric aerobactin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101(10):2722–2727. [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Lorenzo V, Martinez JL. Aerobactin production as a virulence factor: a reevaluation. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1988;7(5):621–629. doi: 10.1007/BF01964239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Soto SM, Smithson A, Horcajada JP, Martinez JA, Mensa JP, Vila J. Implication of biofilm formation in the persistence of urinary tract infection caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli . Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006;12(10):1034–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Johnson JR, O'Bryan TT, Delavari P, et al. Clonal relationships and extended virulence genotypes among Escherichia coli isolates from women with a first or recurrent episode of cystitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;183(10):1508–1517. doi: 10.1086/320198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Johnson JR, Porter S, Thuras P, Castanheira M. The pandemic H30 subclone of sequence type 131 (ST131) as the leading cause of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli infections in the United States (2011–2012) Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017;4(2):ofx089. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Torres AG, Redford P, Welch RA, Payne SM. TonB-dependent systems of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: aerobactin and heme transport and TonB are required for virulence in the mouse. Infect. Immun. 2001;69(10):6179–6185. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6179-6185.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Garcia EC, Brumbaugh AR, Mobley HLT. Redundancy and specificity of Escherichia coli iron acquisition systems during urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 2011;79(3):1225–1235. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01222-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Konopka K, Bindereif A, Neilands JB. Aerobactin-mediated utilization of transferrin iron. Biochemistry. 1982;21(25):6503–6508. doi: 10.1021/bi00268a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Valdebenito M, Crumbliss AL, Winkelmann G, Hantke K. Environmental factors influence the production of enterobactin, salmochelin, aerobactin, and yersiniabactin in Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;296(8):513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersiniabactin iron uptake: mechanisms and role in Yersinia pestis pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 2011;13(10):808–817. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fetherston JD, Bearden SW, Perry RD. YbtA, an AraC-type regulator of the Yersinia pestis pesticin/yersiniabactin receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;22(2):315–325. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Miller MC, Parkin S, Fetherston JD, Perry RD, DeMoll E. Crystal structure of ferric-yersiniabactin, a virulence factor of Yersinia pestis . J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100(9):1495–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ohlemacher SI, Giblin DE, d'Avignon DA, Stapleton AE, Trautner BW, Henderson JP. Enterobacteria secrete an inhibitor of Pseudomonas virulence during clinical bacteriuria. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127(11):4018–4030. doi: 10.1172/JCI92464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Identifies escherichelin as an additional siderophore-like cellular product of Yersinia high pathogenicity island that acts as an inhibitor of the virulence-associated pyochelin siderophore system in Pseudomonas.

- 112.Koh E-I, Robinson AE, Bandara N, Rogers BE, Henderson JP. Copper import in Escherichia coli by the yersiniabactin metallophore system. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:1016–1021. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Establishes yersiniabactin as a metallophore capable of importing both iron and copper ions for nutritional use.