Abstract

The abortion advocacy group Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH) has published over twenty papers based on a case series of women taking part in their Turnaway Study. Following the lead of ANSIRH news releases, major media outlets have described these results as proof that (a) most women who have abortions are glad they did, (b) there is no evidence of negative mental health effects following abortion, and (c) the only women really suffering are those who are being denied late-term abortions due to legal restrictions based on gestational age. Buried in ANSIRH’s papers are the facts that over 68 percent of the women they sought to interview refused, their own evidence confirms that the remnant who did participate were atypical, there are no known benefits from abortion, their methods are misleadingly described, and their results are selectively reported.

Summary: Widely publicized claims regarding the benefits of abortion for women have been discredited. The Turnaway Study, conducted by abortion advocates at thirty abortion clinics, reportedly proves that 95 percent of women have no regrets about their abortions and that abortion causes no mental health problems. But a new exposé reveals that the authors have misled the public, using an unrepresentative, highly biased sample and misleading questions. In fact, over two-thirds of the women approached at the abortion clinics refused to be interviewed, and half of those who agreed dropped out. Refusers and dropouts are known to have more postabortion problems.

Keywords: Abortion, Abortion Decision satisfaction, Abortion mental health, Media bias, Postabortion trauma, Reproductive health, Research bias, Turnaway Study

In 2015, the Washington Post headline boldly proclaimed: “95 Percent of Women Who’ve Had an Abortion Say It Was the Right Decision” (Ingraham 2015). To underscore the credibility of this headline, the reporter explained that this finding was from a University of California study of “667 women having abortions at 30 facilities across the U.S.” Only in the second-to-last paragraph does the article open the door to any limitations on this finding:

The sample size is on the small side, although the researchers note that the cohort of women who participated were demographically similar to women in the U.S. as a whole. And there may be some selection bias happening: Women who agree to speak with researchers about their abortions may be different from women who decline, and their assessments of the procedure after the fact may differ as well. Still, the study deserves note because of the uniformity of the responses.

In short, according to the reporter, these two limitations—small sample size and participation bias—probably make little difference relative to the take-home message due to the “uniformity of the responses.” Readers should therefore trust the headline—and very similar headlines published by Time magazine (Jenkins 2015), The Guardian (Schiller 2015), and most other major news outlets.

Then, just seventeen months later, another study by the same research team was generating more news. The New York Times headline declared, “Abortion Is Found to Have Little Effect on Women’s Mental Health” (Belluck 2016), while WebMD summarized this second study’s key finding as “Women Denied Abortion Endure Mental Health Toll” (Mozes 2016). Meanwhile, Salon combined both themes: “Abortion isn’t linked with mental illness, study shows—but being denied one might be” (Marcotte 2016).

One would think from these headlines that the best available research has now definitively proven that the whole abortion–mental health controversy is nonsense; abortion is a blessing for the vast majority—even 95 percent—of women, with negative effects reserved for those unfortunate women who are being denied access to abortions. Indeed, that is exactly the message that the researchers—who authored these studies for the proabortion research group Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH)—are promoting through both their misleading news releases and their published results.

What is striking is that the major media outlets are so anxious to spread this proabortion propaganda that their science and health reporters have completely abandoned all objectivity. Even the smallest attention to detail should have enabled any reporter to see that the actual “findings” of these studies do not provide a basis for any general conclusions about what “most” women experience after an abortion. Indeed, all of the ANSIRH studies are based on such a weak and biased data set that the real news story is how these studies managed to be published, much less how they became elevated to headline news. Clearly, the complicit medical journals and peer reviewers were so anxious to provide a platform for proabortion propaganda that they not only ignored the poor methodology and superficial analyses but also gave the authors free rein to publish exaggerated conclusions that went far beyond the evidence that they had presented. The key problems with ANSIRH’s Turnaway Study are examined in the following sections.

The Extremely Low Participation Sample—17 Percent to 27 Percent

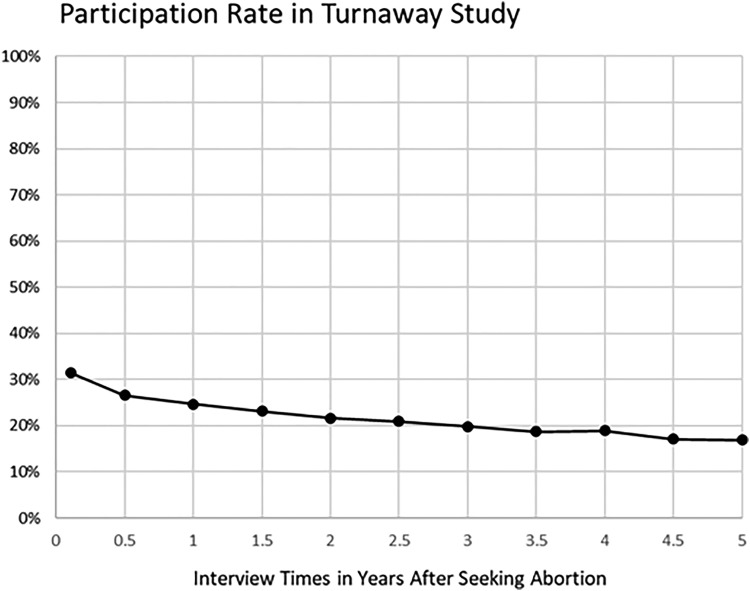

The most glaring problem with the Turnaway Study is the very low participation rate, a problem that the authors never mention in their abstracts or news releases. With the cooperation of thirty different abortion providers, 3,045 women were invited to participate in the study and were promised US$50 in compensation for each phone interview they completed. Despite this financial inducement, only 1,132 (37 percent) agreed to participate. But even among those who agreed, 15.5 percent dropped out before the first interview, which was scheduled for approximately eight days after they went to their respective clinics. Thus, only 31 percent of the invited pool actually participated in at least one interview. Thereafter, another 21 percent, 31 percent, 37 percent, 40 percent, and 46 percent of participants dropped out by the first-, second-, third-, fourth-, and fifth-year interviews, respectively (see Figure 1). To summarize, only 27 percent of the invited women participated at the first six-month interview and only 17 percent participated through to the end of the five-year period.

Figure 1.

Over two-thirds of women approached refused to participate in Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health’s study.

By any measure, this is an abysmal participation rate. But the authors bury these critical facts in supporting documents, leaving them out of every summary statement and news release. Indeed, their news releases boldly assert that 93 percent of those interviewed eight days after seeking an abortion participated “in at least one” of the six month interviews (Rocca et al. 2015). In other words, if you ignore the initial 61 percent refusal rate and the 15 percent dropout rate before the first interview, “only 7 percent” dropped out between the first interview and the second interview. This misleading assertion of a high retention rate was then widely reported by journalists as clear evidence that very few women regret their abortions (Ingraham 2015).

If peer reviewers and journal editors had required the ANSIRH authors to properly describe their study and findings, it would have read something like this: “Of the 20 percent of eligible women who agreed to be interviewed three years after their abortions, 95 percent agreed with the statement that their abortion was the right decision for them.” But any such statement, clarifying that their findings were based on only a small remnant of women approached for feedback, would have made immediately obvious to even the most casual reader that ANSIRH’s results hardly deserved publication, much less major media headlines.

In short, given the fact that 62 percent of the women that ANSIRH approached refused to be interviewed and an additional 37 percent of the initial participants subsequently dropped out before the critical third-year interview, ANSIRH researchers simply have no reliable information about what “most women” believe regarding their abortion decisions.

The Minority Sampled by ANSIRH Are Atypical

With such high nonparticipation rates, the likelihood that the results are biased by self-selection is clearly high. Buried in the details of their paper, even ANSIRH admits that women who reported the highest rates of relief and happiness at the baseline interview eight days after their abortions were most likely to remain in the study (Rocca et al. 2015). Conversely, the women who reported the least relief (and presumably the most negative feelings) eight days after their abortions were most likely to drop out before the three-year assessment of their decision satisfaction.

Numerous studies have also confirmed what common sense suggests: the women who anticipate and experience the most negative reactions to abortion are the least likely to want to participate in interviews that stir up their negative feelings (Adler 1976; Söderberg, Andersson, et al. 1998). It is also known that women who anticipate more negative feelings about their abortions actually do experience more negative feelings (Major et al. 1998). It follows that women refusing to participate in postabortion surveys sponsored by their abortion clinics are accurately anticipating that they do not want the stress of interviews that are likely to stir up their negative feelings.

Indeed, women with a history of abortion report more stress responding to any questions regarding their reproductive history (Reardon and Ney 2000). Notably, the act of avoiding a postabortion evaluation may itself be evidence of a post-traumatic stress response. A study of 246 employees exposed to an industrial explosion revealed that those employees who were most resistant to a psychological checkup following the explosion had the highest rates and most severe cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Without repetitive outreach, much less the leverage of an employer mandate to undergo post-traumatic assessments, 42 percent of the PTSD cases would not have been identified, including 64 percent of the most severe PTSD cases (Weisæth 1989). In the subsequent clinical treatment of these subjects, their therapist noted that “In the clinical analysis of the psychological resistance [to the initial assessment] among the 26 subjects with high PTSS-30 scores, their resistance was mainly found to reflect avoidance behaviour, withdrawal, and social isolation” (Weisæth 1989, 134).

ANSIRH’s Turnaway Study sample is clearly biased toward a subset of women who expected the least negative reactions to their abortion, experienced the least stress relative to discussing their abortions, and perhaps may even have experienced therapeutic benefits from talking about their abortions with researchers who affirmed the “rightness” of their abortion decisions.

An added bias may also have been introduced by the staff members at the thirty participating abortion clinics, who may have introduced their own selection bias by excluding women who were clearly more distressed on the day of their abortions. According to the portion of study protocol that ANSIRH did publish: “It is up to the clinic staff at each recruitment site to keep track of when to recruit abortion clients to match to the turnaways recruited.” In other words, the clinic staff exercised considerable leeway in deciding when to invite women to participate, and this leeway could have been exercised in ways to exclude women whom they may have anticipated were among the worst candidates for abortion. While these women may have refused in any event, the decision not to invite them would not be reflected in the total of women invited to participate. The lack of a randomized selection process, in and of itself, could lead to results that are not generalizable to all women having abortions.

Still more selection bias was introduced by ANSIRH’s own study protocol, which specifically excluded women seeking abortion for suspected fetal anomalies from participation. Notably, this is a high-risk group, which is known to have high rates of postabortion psychological distress (Coleman 2015; Kersting et al. 2009). Excluding this group necessarily results in a study population that is not representative of the true population of women seeking abortions, especially those seeking later-term abortions.

The three groups used in ANSRIH sample are also atypical in other ways. The first group consisted of 254 women who had abortions during the first trimester. The second group included 413 women who had abortions at the end of their second trimester, within two weeks of the legal limits on late-term abortions. The proportion of women in these two groups is itself very atypical of the general population of women having abortions, of whom approximately 90 percent have their abortions during the first trimester.

The third group of women surveyed by ANSRIH is actually the core comparison group after which the Turnaway Study was named. It was comprised of 210 women who sought abortions after the gestational cutoff age allowed by state law (typically over twenty-four weeks) and were, therefore, turned away by the clinic staff. But even this comparison group was muddied by the fact that at least fifty (24 percent) of these turnaways subsequently had abortions in another state or had a miscarriage. (No statistic is reported on how many had miscarriages or abortions, only that they did not deliver.) In any event, in several of the analyses in which ANSIRH claims it is comparing women who had abortions to those “denied abortions,” the researchers frequently fail to clarify that they are actually comparing women who had abortions to a “turnaway group” of which one-fourth had abortions or miscarriages just a few weeks later.

This brings us to yet another problem with the comparisons reported by ANSIRH. There is no accounting for prior or subsequent abortion history. It is well known that there is a dose effect; women having multiple abortions have more mental health problems (Sullins 2016). How many women in the turnaway group had a history of prior abortions before carrying to term? And in the course of five years of follow-up, how many women in all of the groups had subsequent abortions? ANSIRH ignores these questions…or at least doesn’t report on them. In any event, absent a control group of women who have never been exposed to abortion, the Turnaway Study cannot tell us anything about the differences between women who have abortions and those who do not.

In summary, the Turnaway Study uses three groups of volunteers who were invited through a nonrandom process that introduces selection bias via the clinic workers, the research protocol, and the inherent problem of self-selection bias. Moreover, ANSIRH failed to collect, or at least control for, the entire reproductive history of all the subjects. As a result, ANSIRH’s analyses are confined to just two of the groups of women known to have had at least one early- or late-term abortion and a third group that is known to have sought a late-term abortion but of whom there is unknown history of prior or subsequent abortions. In short, the ANSIRH’s sample and study design are so packed with ambiguities that it is impossible to generalize their results in any meaningful way.

Mischaracterization of Their Study Design

The ANSIRH authors frequently describe their study as a “prospective longitudinal cohort study.” But in fact, since they do not have data collected on the women prior to seeking abortion, much less becoming pregnant, their study design must properly be classified as a “case series”(Dekkers et al. 2012). This distinction is clarified by Song and Chung (2010):

An important distinction lies between cohort studies and case series. The distinguishing feature between these two types of studies is the presence of a control, or unexposed, group. Contrasting with epidemiological cohort studies, case series are descriptive studies following one small group of subjects. In essence, they are extensions of case reports. Usually the cases are obtained from the authors’ experiences, generally involve a small number of patients, and more importantly, lack a control group. There is often confusion in designating studies as “cohort studies” when only one group of subjects is examined. Yet, unless a second comparative group serving as a control is present, these studies are defined as case series. (p.3)

While it is true that the ANSIRH authors claim that their sample of “women denied abortions” is the “unexposed group,” this is clearly an improper classification for three reasons:

all of the women were already exposed to a problem pregnancy;

all of the women had already gone through the process of seeking an abortion, which itself may be all or a portion of the traumatic part of some abortion experiences; and

the unexposed group includes women who already had a history of multiple pregnancy experiences, including abortions and miscarriages, either before or after the index pregnancy, or both.

The proper description of this study design as a case series is a very important distinction. The mischaracterization of the study design as a prospective longitudinal cohort study gives the false impression that ANSIRH’s methodology meets the criteria of a true, high-quality prospective study that gathers data on a representative sample of people both before and after they are exposed to the subject of interest—in this case, a pregnancy subject to abortion. In fact, the Turnaway Study is not a prospective study at all. It is merely a case series report on a highly self-selected sample with a very high attrition rate.

Ironically, as an excuse for the low participation rate in their prospective longitudinal cohort study, ANSIRH points out that many other studies conducted by or with the cooperation of abortion clinics have similar “rates as low as 20 percent.” In short, readers are asked to ignore the problems implicit in self-selection bias, since ANSIRH’s own opt-out rates are similar to the poor results that have plagued other proabortion case series.

What makes this claim especially ironic is that the few true, prospective, longitudinal cohort studies that have examined mental health risks associated with abortion have had retention rates of 88 percent (Fergusson, Horwood, and Boden 2008, 2009; Fergusson, Horwood, and Ridder 2006; Sullins 2016) or higher (Reardon et al. 2003; Sullins 2016). Chief among these are studies based on New Zealand’s Christchurch Health and Developmental Study. That study followed a cohort of women from birth to thirty years of age and had an 88 percent retention rate.

Notably, the Christchurch studies, which have the most extensive preabortion history data of any abortion studies ever published, revealed that abortion is significantly associated with increased rates of suicidal tendencies, substance abuse, depression, anxiety, and the total number of mental health problems (Fergusson, Horwood, and Boden 2008, 2009; Fergusson, Horwood, and Ridder 2006). Yet, despite their methodological superiority, the Christchurch studies, like others contradicting the Turnaway Study findings (Coleman 2011; Reardon et al. 2003; Sullins 2016), are consistently overlooked by ANSIRH and the reporters covering their studies. As a result, the major media outlets are giving headlines to fatally flawed studies that promote proabortion messages while high-quality studies are routinely ignored.

Selective Reporting of Results

Another major problem found in the ANSIRH studies is selective reporting. For example, the key finding reported in the abstract of one paper was that “compared with having an abortion, being denied an abortion may be associated with greater risk of initially experiencing adverse psychological outcomes” (Biggs et al. 2016, 1). But it is only when one reads the details of the paper that one discovers that this “greater risk” was observed only in regard to a single statistic: anxiety scores just one week after women seeking a late-term abortion were turned away.

This finding is hardly remarkable for two reasons. First, abortion is both a stress reliever and a stress inducer (Speckhard and Rue 1992). In the short term, a decline in anxiety following an abortion is common, even while other negative feelings such as depression or guilt may be increasing. Second, the comparison group of women being turned away from a late-term abortion continues to face the stresses related to making new plans including efforts to find an abortion elsewhere. It is hardly remarkable to discover that eight days later, their anxiety levels are still marginally higher than those of the women who aborted. What is remarkable is how the ANSIRH researchers turn this single benign data point into a declaration that women “denied an abortion” face greater risk of “adverse psychological outcomes” (plural)—a conclusion widely reported by the proabortion press.

In fact, ANSIRH’s own data actually revealed that beyond this first week, the women denied an abortion who actually did carry to term had significant improvements in anxiety, depression, and self-esteem. Indeed, the researchers admitted that they could observe no significant differences between the groups. But this is only admitted in the details of the study, not the abstract, conclusions, or news releases.

Instead, ANSIRH’s spin on their findings was women who abort do not have more psychological problems than women who give birth. But the women giving birth in the Turnaway group are atypical. Moreover, the rate of psychological problems among women aborting in this sample is likely skewed by several forms of selection bias discussed earlier that may tilt the sample toward women who are least likely to report psychological problems after their abortions.

But ANSIRH’s spin how aborting women did as well as those who gave birth actually includes an admission most damaging to their own ideology. Specifically, ANSIRH’s own evidence suggests that there are no persistent mental health risks associated with women being denied an abortion. In other words, an equally valid headline would read: “Women Denied Abortions Face No Long-Term Mental-Health Problems.” That may help to explain why ANSIRH chose to elevate a single anxiety score accessed eight days after begin turned away from an abortion (including the anxiety of women still looking for an alternative place to get an abortion) into their misleading claim that women who are denied abortions may face more mental health problems than women who are provided abortions (Marcotte 2016).

A similar distortion occurs in ANSIRH’s assertion that women having an abortion are overwhelmingly convinced that they made the “right choice.” In fact, that conclusion was also based on a single question asking whether the “abortion was right for them.” But what does “right for you” even mean? Morally right? Right for achieving a specific goal? or that it is simply the best decision of many bad options given your specific situation? In short, this single question lacks any nuance. Indeed, the opportunity for nuance was further restricted by requiring women to answer with just a “yes,” “no,” or “uncertain.” A better research approach would have been to have this question rated on a numeric scale (e.g., 1–10), especially in order to better identify whether there was any shifting of attitudes over the five years examined.

This question of rightness also invites reaction formation, a defense mechanism that tends to affirm “what is done is done” even if there are actually unresolved issues. In addition, the process of phone interviews may incline volunteers to please the interviewer with the expected affirmation. Voicing dissatisfaction may invite more anxiety-provoking thoughts. Responding the way one is expected to respond avoids any deeper reflection.

A more serious investigation of decision satisfaction should have included additional questions to better gauge the subjects’ thoughts. For example, in a more in-depth study from Sweden that included a one-year postabortion interview of 847 women (after a 33 percent self-exclusion rate), 80 percent of the women reported that they were satisfied with their decision to abort, but 76 percent also stated that they would never abort again if faced with an unwanted pregnancy (Söderberg, Janzon, and Sjöberg 1998). This second finding suggests that an elevated unwillingness to have another abortion may tell us more about what is going on in a woman’s mind than just her expression of the rightness of a past decision that she cannot change.

The simple fact is that positive feelings about an abortion generally coexist with profoundly negative feelings (Kero and Lalos 2000; Major et al. 2000; Miller 1992; Rue et al. 2004; Söderberg, Janzon, and Sjöberg 1998; Zimmerman 1977). In one study, “Almost one-half also had parallel feelings of guilt, as they regarded the abortion as a violation of their ethical values. The majority of the sample expressed relief while simultaneously experiencing the termination of the pregnancy as a loss coupled with feelings of grief/emptiness” (Kero and Lalos 2000). Another study found that 56 percent of women chose both positive and negative words to describe their upcoming abortion, with 33 percent choosing only negative words and only 11 percent choosing only positive words (Kero et al. 2001).

It is difficult to imagine that the ANSIRH researchers are ignorant of these facts. It is also difficult to imagine that their questionnaire did not include additional questions that might shed more light on these issues. On the other hand, it is easy to imagine that ANSIRH would selectively choose to withhold information on questions that produced results that did not advance their ideological agenda. In fact, ANSIRH has refused requests to publish their complete questionnaire, much less to make any of their data available for reanalysis. They have even published results in journals, which require data to be made available for others, but have claimed and received exemptions from doing so based on an assertion of their duty to protect patient privacy (Rocca et al. 2015). But this excuse for withholding data lacks merit. As long as the data is deidentified, there is no legitimate privacy or compliance issues with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). In fact, ANSIRH’s decision to deny other researchers the opportunity to reanalyze their findings is a direct violation of the American Psychological Association’s (2010) standards, which uphold as an ethical obligation the duty to make data available for reanalysis by other researchers.

Conclusion

To date, ANSIRH has published over two dozen papers based on their Turnaway Study. All share the fundamental problems described above, plus unique limitations associated with each. ANSIRH’s attempt to examine how women fared, who sought abortions after the legal gestational limits on abortion, is understandable. It is even a worthy research objective. But there is no intellectual defense for their effort to promote their ideological agenda by means of minimizing or suppressing relevant information or for their exaggerated claims regarding sparse and unrepresentative findings.

Worst of all, ANSIRH is not alone in deceiving the public. The fact that so many journal editors, peer reviewers, and journalists have cooperated in their effort to proclaim overgeneralized conclusions as fact, while turning attention away from all the inconvenient details that undermine those conclusions, is even more concerning. Are prochoice ideological biases truly so deep that editors, reviewers, and journalists simply do not notice the problems with this research? Or are they consciously choosing to collaborate in ANSIRH’s efforts to generate misleading headlines? Whatever the answers to these questions regarding research ethics and media coverage may be, women and their partners deserve better.

Biographical Note

David C. Reardon, PhD, is a leader in promoting post-abortion-healing programs and a prominent researcher on the after effects of abortion. His studies showing elevated rates of suicide, psychiatric hospitalization, substance abuse, and other health problems associated with abortion have been published in the British Medical Journal, the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and other leading medical journals. He is the author of five books including The Jericho Plan: Breaking Down the Walls Which Prevent Post-abortion Healing and Making Abortion Rare: A Healing Strategy for a Divided Nation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: David C. Reardon  http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4437-2434

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4437-2434

References

- Adler N. E. 1976. “Sample Attrition in Studies of Psychosocial Sequelae of Abortion: How Great a Problem?” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 6 no. 3: 240–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1976.tb01329.x. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. 2010. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx#8_14.

- Belluck P. 2016. “Abortion Is Found to Have Little Effect on Women’s Mental Health.” New York Times, December 14 https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/14/health/abortion-mental-health.html?_r=0.

- Biggs M. A., Upadhyay U. D., McCulloch C. E., Foster D. G. 2016. “Women’s Mental Health and Well-being 5 Years after Receiving or Being Denied an Abortion: A Prospective, Longitudinal Cohort Study.” JAMA Psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman P. K. 2011. “Abortion and Mental Health: Quantitative Synthesis and Analysis of Research Published 1995–2009.” British Journal of Psychiatry. 199 no. 3: 180–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman P. K. 2015. “Diagnosis of Fetal Anomaly and the Increased Maternal Psychological Toll Associated with Pregnancy Termination.” Issues in Law & Medicine 30 no. 1: 3–23. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26103706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers O. M., Egger M., Altman D. G., Vandenbroucke J. P. 2012. “Distinguishing Case Series from Cohort Studies.” Annals of Internal Medicine 156 no. 1_Part_1: 37 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-1-201201030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D. M., Horwood L. J., Boden J. M. 2008. “Abortion and Mental Health Disorders: Evidence from a 30-year Longitudinal Study.” British Journal of Psychiatry 193 no. 6: 444–51. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D. M., Horwood L. J., Boden J. M. 2009. “Reactions to Abortion and Subsequent Mental Health.” British Journal of Psychiatry 195 no. 5: 420–26. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.066068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D. M., Horwood L. J., Ridder E. M. 2006. “Abortion in Young Women and Subsequent Mental Health.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 47 no. 1: 16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham C. 2015. “95 Percent of Women Who’ve Had an Abortion Say It Was the Right Decision.” Washington Post, July 14 Washington, DC: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/07/14/95-percent-of-women-whove-had-an-abortion-say-it-was-the-right-decision/. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins N. 2015. “Hardly Any Women Regret Having an Abortion, a New Study Finds.” Time, July 14, 10 http://time.com/3956781/women-abortion-regret-reproductive-health/.

- Kero A., Högberg U., Jacobsson L., Lalos A. 2001. “Legal Abortion: A Painful Necessity.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 53 no. 11: 1481–90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11710423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kero A., Lalos A. 2000. “Ambivalence—A Logical Response to Legal Abortion: A Prospective Study among Women and Men.” Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology 21 no. 2: 81–91. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10994180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersting A., Kroker K., Steinhard J., Hoernig-Franz I., Wesselmann U., Luedorff K., Ohrmann P., Arolt V., Suslow T. 2009. “Psychological Impact on Women after Second and Third Trimester Termination of Pregnancy due to Fetal Anomalies versus Women after Preterm Birth: A 14-month Follow Up Study.” Archives of Women’s Mental Health 12 no. 4: 193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B., Cozzarelli C., Cooper M. L., Zubek J., Richards C., Wilhite M., Gramzow R. H. 2000. “Psychological Responses of Women after First-trimester Abortion.” Archives of General Psychiatry 57 no. 8: 777–84. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0033842045&partnerID=40&md5=b03947a82b10e60c9e7846b1bb5d680d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B., Richards C., Cooper M. L., Cozzarelli C., Zubek J. 1998. “Personal Resilience, Cognitive Appraisals, and Coping: An Integrative Model of Adjustment to Abortion.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74 no. 3: 735–52. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9523416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte A. 2016. “Abortion Isn’t Linked with Mental Illness, Study Shows—but Being Denied One Might Be.” Salon, December 14 http://www.salon.com/2016/12/14/abortion-isnt-linked-with-mental-illness-study-shows-but-being-denied-one-might-be/.

- Miller W. 1992. “An Empirical Study of the Psychological Antecedents and Consequences of Induced Abortion.” Journal of Social Issues 48 no. 3: 67–93. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1992.tb00898.x/abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Mozes A. 2016. “Women Denied Abortion Endure Mental Health Toll.” WebMD, December 14 http://www.webmd.com/women/news/20161214/women-denied-an-abortion-endure-mental-health-toll-study#1.

- Reardon D. C., Cougle J. R., Rue V. M., Shuping M. W., Coleman P. K., Ney P. G. 2003. “Psychiatric Admissions of Low-income Women following Abortion and Childbirth.” CMAJ 168 no. 10: 1253–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon D. C., Ney P. G. 2000. “Abortion and Subsequent Substance Abuse.” The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 26 no. 1: 61–75. doi: 10.1081/ADA-100100591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca C. H., Kimport K., Roberts S. C. M., Gould H., Neuhaus J., Foster D. G. 2015. “Decision Rightness and Emotional Responses to Abortion in the United States: A Longitudinal Study.” PLoS One 10 no. 7: e0128832 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rue V. M., Coleman P. K., Rue J. J., Reardon D. C. 2004. “Induced Abortion and Traumatic Stress: A Preliminary Comparison of American and Russian Women.” Medical Science Monitor 10 no. 10: SR5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller R. 2015. “Women Rarely Regret Their Abortions. Why Don’t We Believe Them?” The Guardian, July 14 https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/womens-blog/2015/jul/14/women-rarely-regret-abortions-us-study-uk-reproductive-rights.

- Söderberg H., Andersson C., Janzon L., Sjöberg N. O. 1998. “Selection Bias in a Study on How Women Experienced Induced Abortion.” European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 77 no. 1: 67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)00223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderberg H., Janzon L., Sjöberg N. O. 1998. “Emotional Distress following Induced Abortion: A Study of Its Incidence and Determinants among Abortees in Malmö, Sweden.” European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 79 no. 2: 173–78. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9720837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J. W., Chung K. C. 2010. “Observational Studies: Cohort and Case-control Studies.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 126 no. 6: 2234–42. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f44abc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speckhard A. C., Rue V. M. 1992. “Postabortion Syndrome: An Emerging Public Health Concern.” Journal of Social Issues 48 no. 3: 95–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1992.tb00899.x. [Google Scholar]

- Sullins D. P. 2016. “Abortion, Substance Abuse and Mental Health in Early Adulthood: Thirteen-Year Longitudinal Evidence from the United States.” SAGE Open Medicine 4:1–11 2050312116665997 doi: 10.1177/2050312116665997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisæth L. 1989. “Importance of High Response Rates in Traumatic Stress Research.” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 80 no. s355: 131–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb05262.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M. K. 1977. Passage through Abortion: The Personal and Social Reality of Women’s Experiences. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]