Abstract

Aims and Objectives:

The aim of this study is to compare the esthetic improvement of white spot lesions (WSLs) treated by icon, sodium fluoride (NaF), and bioactive glass using VITA Easyshade® spectrophotometer.

Methodology:

Ninety intact human maxillary central incisors were collected and artificial WSLs were created on facial surface having dimensions of 4 mm × 4 mm by immersing in demineralized solution for 4 days, baseline comparisons were performed by measuring the color of the WSLs compared to the adjacent sound enamel. All samples were divided into three groups of 30 each. Three groups were Group 1: Treated by NaF, Group 2: Treated by the bioactive glass, and Group 3: ICON®-DMG America (Resin infiltration). After treatment, the specimens of all groups were stored in artificial saliva and reevaluated at 4 and 8 weeks after the beginning of the treatments with VITA Easyshade® spectrophotometer.

Results:

Statistical analysis was performed with One-way analysis of variance. Post hoc analysis with the Tukey's honest significant difference test was used to compare the data between the groups. Among three groups, resin infiltration has significant color change (ΔE) of infiltrated lesions when compared to other treatment groups (P < 0.001)

Conclusion:

Within the limitations of this study, it can be concluded resin infiltration (ICON®) can improve the esthetic characteristics of WSLs. Resin (ICON®) is a better treatment option when compared to bioactive glass and NaF as concerned to esthetics.

Keywords: Bioactive glass, esthetic improvement, ICON® resin infiltration, sodium fluoride, white spot lesions

INTRODUCTION

Esthetics is an important aspect in dentistry and dental education. With the continuing advances in dentistry and dental technology, there are now an abundance of options that make it easy to perform esthetic dental procedures. The most conservative of all esthetic procedures is one that involves no tooth removal at all. This can be achieved by “minimal intervention dentistry.”

White spot lesions (WSLs) are early signs of demineralization under the intact enamel, which may or may not lead to the development of caries. WSLs occur when the pathogenic bacteria have breached the enamel layer and organic acids produced by the bacteria have leached out a certain amount of calcium and phosphate ions that may or may not be replaced naturally by the remineralization process.[1] The approach for managing incipient carious lesions (WSLs) is the clinical condition that better illustrates the implementation of this philosophy, having in mind the integrity of the tooth structure and the inherent possibility of remineralization. The first line of treatment of white spot is remineralization. There are creams, pastes, and topical remineralisation treatments such as fluoride therapy, casein– phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate pastes, bioactive glass (calcium sodium phosphosilicate). Bleaching, invasive approaches such as microabrasion, conventional bonding, and various types of veneers are the other modes of treatment for WSLs.[2]

Very few studies have been done to check color improvement of WSL following treatment with sodium fluoride (NaF) gel, bioactive glass, and ICON resin infiltration. Hence, the aim of this study was to compare the esthetic improvement of WSLs treated by NaF gel, bioactive glass, and resin infiltration (ICON®) using VITA Easyshade® spectrophotometer.

METHODOLOGY

Intact permanent maxillary central incisors with fully formed apices were included in the study. Teeth with carious lesions, erosion, attrition, any restorations, root canal treated teeth, teeth with developmental anomalies,and chemically treated teeth were excluded from the study.

The teeth were stored in 0.1% Thymol until further processing.

Demineralization procedure

A total of 90 maxillary permanent central incisors were collected and stored in thymol solution until the study was conducted. On the day of study, the teeth samples were removed from the solution, washed, and dried for use. All teeth samples were coated with a nail varnish, leaving a 4 mm × 4 mm window which was prepared by placing a wax on the buccal surface. A demineralizing solution was prepared (2.2 mM calcium chloride, 2.2 mM monopotassium phosphate, 0.05 mM acetic acid having pH adjusted to 4.4 and 1M potassium hydroxide) and all the samples were immersed in this demineralizing solution for 4 days to create artificial WSLs.

Colour measurement was performed before (baseline) and after the creation of WSL using VITA Easyshade® spectrophotometer.

Preparation of artificial saliva

Artificial saliva was prepared according to the formulation of Gohring et al. and consisted of hydrogen carbonate (22.1 mmol/L), potassium (16.1 mmol/L), sodium (14.5 mmol/L), hydrogen phosphate (2.6 mmol/L), boric acid (0.8 mmol/L), calcium (0.7 mmol/L), thiocyanate (0.2 mmol/L), and magnesium (0.2 mmol/L). The pH will be maintained between 7.4 and 7.8.

The specimens were then divided into three groups (n = 30), accordingly caries treatment was employed.

Grouping and treatment interventions

Group 1: 2% neutral fluoride gel (NaF) – 1 ml of 2% NaF neutral gel was applied weekly for 1 min on the surface of the specimens for 8 weeks. After the gel application, the specimens were rinsed with de-ionized water and stored in artificial saliva

Group 2: Bioactive glass (Vantej) was prepared as slurry. The slurry was prepared with de-ionized water (P/L ratio of 1 g/ml) and applied without any mechanical agitation. The surface remineralization treatments were conducted for 7 days and refreshed daily

Group 3: ICON (resin infiltration) – specimens were resin infiltrated (Icon1, DMG, Hamburg, Germany) and stored in artificial saliva for 8 weeks. The infiltration procedure was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The specimens of all groups stored in artificial saliva and were re-evaluated at 4 and 8 weeks after the beginning of the treatments.

Spectrophotometric evaluation of color change

The probe tip was placed on an area of the enamel surface that has underlying dentin (middle to the cervical area). The probe tip was placed perpendicular and flushed to the tooth surface. While holding the probe tip steady against the dentine center of the tooth, measurement button was pressed and held against the tooth until two rapid “beeps” were heard to indicate completion of the measurement. VITA Easyshade® Advance will display the results of the measurement.

Optical results were analyzed using the CIE-L*a*b* color system. The CIE L*a*b system records colorimetric parameters three dimensionally: Lightness (L*; 0–100), green-red chromacity (a*; _150 to + 100) and blue-yellow chromacity (b*; _100 to + 150). CIE L* a*b* values were measured and calculated using the equation ΔE = ([ΔL*]2+ [Δa*]2+ [Δb*]2) 1/2.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 21.0. (Amonk, IBM Corp., NY) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed with mean and standard deviation and one-way analysis of variance. Post hoc analysis with the Tukeys honest significant difference test was used to compare the data between the groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The present in vitro study was done to compare and evaluate the esthetic improvement of WSLs treated by Icon, NaF and bioactive glass in artificially induced enamel lesions of permanent maxillary central incisors.

Comparison of color changes among three different groups:

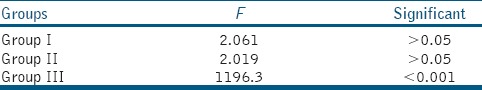

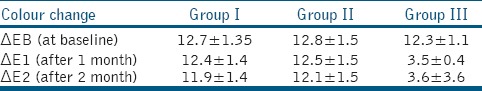

After demineralization L*a*b* values were recorded and were compared with those of adjacent sound enamel. Color difference, ΔEB was calculated. At baseline, demineralized lesions showed considerable color differences compared with sound enamel. Before WSL treatment, the mean ΔEB for Group I was 12.70, for Group II was 12.73, and for Group III was 12.26. Statistical analysis for comparison of color changes among 3 groups was done using ANOVA test. Among three groups, resin infiltration significantly decreased color differences (ΔE) of infiltrated lesions when compared to other treatment groups (P < 0.001) [Table 1], thus achieving visual masking (ΔE <3.6). There was a decrease in ΔE value in NaF and bioactive glass groups from the baseline, but a decrease in the color difference is not statistically significant [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Tabulated column showing P values of three groups

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics showing colour changes, ΔEB (ΔE at baseline), ΔE1 (ΔE after 1 month) andΔE2 (ΔE after 2 months) for each of the specimen in Group 1, Group 2 and Group 3

Comparison of color changes within the groups:

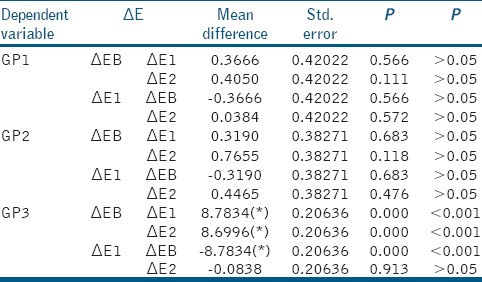

Statistical analysis for comparison of color changes within the group over 2 months time period was done using Tukey test. The color of the WSLs in the icon treatment group was improved significantly (P < 0.001) by the resin infiltration treatment from baseline to 1 month and had the lowest mean ΔE1 ( 3.47 ± 0.3) compared with the other treatment groups [Tables 2 and 3]. The difference in ΔE1 and ΔE2 (color change from 1 month to 2 months) was not statistically significant in resin infiltration group.

Table 3.

Comparison among groups using Tukey HSD Test

There were no significant changes in ΔE values in NaF and bioactive glass group with time during the 1–2 months after treatment (P > 0.05) [Table 3].

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the in vitro effect of Icon, NaF and bioactive glass on the esthetic improvement of WSLs. It has been known since the 1980s that fluoride controls caries predominantly through its topical effect. Fluoride inhibits demineralization, enhances remineralization and may inhibit essential bacterial activity. The fluoride integrated in the enamel surface (as fluorapatite, [FAP]) makes enamel more resistant to demineralization than HAP during acid challenge. FAP is less soluble due to the incorporation of fluoride and washing out of carbonate. Fluoridated saliva not only decreases critical pH but also further inhibits demineralization of the deposited calcium fluoride at the tooth surface.[3]

Bioactive glass is made of synthetic material containing sodium, calcium, phosphorous and silica (sodium calcium phospho silicate), which are all elements naturally found in the body. Recently, bioactive glass materials have been introduced in many fields of dentistry. It is one of the agents in nonfluoride remineralization strategies. Considering the efficacy of bioactive glass as a good remineralizing agent, it is selected as one of the treatment groups in the present study.

Caries infiltration is a novel treatment option for WSLs and might bridge the gap between nonoperative and operative modalities. It is a micro-invasive technology that fills, reinforces and stabilizes demineralized enamel, without drilling or sacrificing healthy tooth structure. It has also been shown to inhibit caries progression in lesions that are too advanced for fluoride therapy. Hence ICON® resin infiltration is selected as one of the treatment groups in the present study.

In the present study, color measurement was done using a VITA Easyshade® guide spectrophotometer. The instrumental color analysis offers a potential advantage over visual color determination because instrumental readings are objective, can be quantified, and are more rapidly obtained.[4] Spectrophotometers are among the most accurate, useful, and flexible instruments for color matching. A spectrophotometer functions by measuring the spectral reflectance or transmittance curve of a specimen. They are useful in the measurement of surface color.

This study compared the effects of three commonly used treatment modalities for WSLs during a follow-up of 8 weeks (2 months) after treatment. Significant decreases of ΔE mean values were found in the Icon group after the treatment [Table 2], indicating that Icon had the best effectiveness of the three treatments in masking the WSLs and returning the enamel to its natural color. This may be because the air or water in the microporosities of WSLs was replaced with resin, leading to less light scattering within the enamel.

Sound enamel has a refractive index (RI) of 1.62 while demineralized WSLs have many pores filled with water (RI = 1.33) or air (RI = 1.00). The difference in RIs between the enamel crystals and medium inside the porosities affects the light scattering and gives these lesions a whitish appearance, especially when desiccated.[1] When the micropores of WSLs were infiltrated by resin (RI = 1.46), which has a similar RI as enamel and cannot evaporate, the difference in RIs between porosities and enamel was decreased to a negligible level, and the WSLs regained translucency, appearing similar to that of the surrounding sound enamel.

Because a ΔE value of <3.6 is considered a clinically acceptable color difference,[5] an average ΔE of 3.4 ± 0.3 after resin infiltration in our study indicated a better and acceptable color recovery compared with NaF or bioactive glass [Table 2].

It was found that remineralization of WSLs by the artificial saliva for the NaF and bioactive glass treatment groups was a slow process because of its dependence on the deposition of calcium ions.[6] In contrast, the low viscous resin could penetrate into deeper lesions and improve the esthetic appearance of the WSL immediately after treatment. That explains why the ΔE immediately showed significant recovery for the Icon group, whereas there was decrease in ΔE only after 2 months of remineralization in the NaF and Bioactive glass groups in this study. Although there is decrease in ΔE values in NaF and Bioactive glass group after 1 and 2 months when compared to baseline values, but are not clinically and statistically significant (ΔE >3.6) [Table 2].

This finding are supported by the findings of Paris and Meyer-Lueckel[7] and Yuan et al.,[8] who stated that significant color change and camouflage of WSLs can be achieved with resin infiltrants with RI which is close to the RI of enamel.

In the present study if we compare the color masking ability of NaF and Bioactive glass group, ΔE values after 1 and 2 months were decreased but not to a clinically acceptable range (ΔE >3.6) when compared to baseline and the decrease in the values are not statistically significant [Table 1].

The reason for the above finding may be because remineralization of WSLs by the artificial saliva for the NaF and bioactive glass treatment groups was a slow process because of its dependence on the deposition of calcium ions. In the present study, remineralization of WSLs by NaF and bioactive glass was done for 2 months in a weekly interval, previous studies shown that improvement depends on the severity of lesions and it needs more than 6 months for the treatment to be effective.[9,10]

Vahid Golpayegani et al. stated that bioactive glass dentifrice appears to have a greater effect on remineralization of carious-like lesions when compared to that of fluoride-containing dentifrice in permanent teeth,[11] this finding was contradicted by Lewis et al. saying that the calcium-containing dentifrices have significantly lower remineralization ability even in the presence of fluoride paste (NaF).[10]

In the present study, the color improvement was not up to clinically acceptable range improvement in both NaF and Bioactive glass group. The reason may be because the remineralization of WSLs by the artificial saliva for the NaF and Bioactive glass treatment groups was a slow process because of its dependence on the deposition of calcium ions. So, further studies should be extended to determine how long the remineralization modalities take to restore the WSLs to a normal enamel appearance.

In the present study, artificial saliva was used in order to simulate the oral condition for releasing the bioactive content into the environment. This condition helps the calcium sodium phosphosilicate bioactive glass to gradually substitute by hydrogen ions. As the process continues, a thick layer of calcium and phosphate precipitates on to the tooth surface with an increased pH of the environment preventing the demineralization process.

Resin infiltration was originally developed to obstruct the diffusion pathways for acids in order to protect internal enamel, with a masking effect being an additional advantage.[12] Microabrasion, which has been commonly used for treating WSLs, can remove up to 250 μm of enamel.[13] In contrast, in the clinical practice of resin infiltration; The 15% HCl gel used to prepare the surface and open the pores of WSLs removes only about 40 μm of the surface layer. In our study, no cavitation occurred after etching with the HCl gel, and the subsequent resin infiltration helped strengthen the WSL structures.[14] Because resin infiltration can immediately restore the color of WSLs, it saves time for patients and clinicians. In addition, resin infiltration maintained color stability for at least 2 months after application in our study. These features indicate that resin infiltration was the best of the techniques tested for the treatment of WSLs, which is consistent with a previous study that showed that resin infiltration was an effective treatment for masking WSLs and resisting a new acid challenge.[15] However, the long-term effect of resin infiltration on WSLs in clinical practice should be studied further. The fluoride and Bioactive glass treatment and remineralization times should be extended to determine how long the remineralization modalities take to restore the WSLs to a normal enamel appearance. In addition, a randomized controlled clinical trial comparing these different treatment modalities would provide valuable information for dental practitioners.

CONCLUSION

With in the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that resin infiltration (ICON®) can improve the esthetic characteristics of white spot lesions. Resin infiltration is a better treatment option when compared to Bioactive glass and NaF as concerned to esthetics. It can immediately restore the color of white spot lesions and stop the progression of emerging caries by blocking diffusion pathways. However, the long term effect of resin infiltration on white spot lesions in clinical practice should be studied further.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kidd EA, Fejerskov O. What constitutes dental caries? Histopathology of carious enamel and dentin related to the action of cariogenic biofilms. J Dent Res. 2004;83:C35–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301s07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shivanna V, Shivakumar B. Novel treatment of white spot lesions: A report of two cases. J Conserv Dent. 2011;14:423–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.87217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naoum S, O'Regan J, Ellakwa A, Benkhart R, Swain M, Martin E, et al. The effect of repeated fluoride recharge and storage media on bond durability of fluoride rechargeable giomer bonding agent. Aust Dent J. 2012;57:178–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2012.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okubo SR, Kanawati A, Richards MW, Childress S. Evaluation of visual and instrument shade matching. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;80:642–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(98)70049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behnan SM, Arruda AO, González-Cabezas C, Sohn W, Peters MC. In vitro evaluation of various treatments to prevent demineralization next to orthodontic brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138:712.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jham AC. Masters Thesis. Iowa City, Iowa: Univ of Iowa; 2010. The Efficacy of Novamin Powered Technology Oravive and Topexrenew, Crest and Prevident 5000 Plus in Preventing Enamel Demineralization and White Spot Lesion formation. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H. Masking of labial enamel white spot lesions by resin infiltration – A clinical report. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:713–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan H, Li J, Chen L, Cheng L, Cannon RD, Mei L, et al. Esthetic comparison of white-spot lesion treatment modalities using spectrometry and fluorescence. Angle Orthod. 2014;84:343–9. doi: 10.2319/032113-232.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beerens MW, Boekitwetan F, van der Veen MH, ten Cate JM. White spot lesions after orthodontic treatment assessed by clinical photographs and by quantitative light-induced fluorescence imaging; a retrospective study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2015;73:441–6. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2014.980846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis RD, Marken BF, Smith SR. Anti-plaque efficacy of a chalk-based antimicrobial dentifrice. SADJ. 2001;56:178–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vahid Golpayegani M, Sohrabi A, Biria M, Ansari G. Remineralization effect of topical NovaMin versus sodium fluoride (1.1%) on caries-like lesions in permanent teeth. J Dent (Tehran) 2012;9:68–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paris S, Hopfenmuller W, Meyer-Lueckel H. Resin infiltration of caries lesions: An efficacy randomized trial. J Dent Res. 2010;89:823–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034510369289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy TC, Willmot DR, Rodd HD. Management of postorthodontic demineralized white lesions with microabrasion: A quantitative assessment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kantovitz KR, Pascon FM, Nobre-dos-Santos M, Puppin-Rontani RM. Review of the effects of infiltrants and sealers on non-cavitated enamel lesions. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8:295–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocha Gomes Torres C, Borges AB, Torres LM, Gomes IS, de Oliveira RS. Effect of caries infiltration technique and fluoride therapy on the colour masking of white spot lesions. J Dent. 2011;39:202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]