Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this randomized, controlled, double-blinded, clinical study is to evaluate and compare the clinical effectiveness of low-level diode GaAlAs laser and glutaraldehyde-based topical desensitizing agent on cervical dentin hypersensitivity with the help of visual analog scale (VAS).

Materials and Methods:

Fifty teeth of patients aged between 20 and 50 years were included, and VAS was used to assess the dentin hypersensitivity. The teeth were randomly allocated to either Group 1 or 2 using flip coin technique. Group 1 received glutaraldehyde desensitizer and Group 2 received 905 nm low-level laser. The sensitivity scores were recorded, immediately, after1 week and 3 months after therapy. Data was analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test for intergroup comparison and Friedman's test for intragroup comparison.

Results:

There was a significant reduction in pain in both the groups at 3 months evaluation (P = 0.001).However, Group 2 showed a significant decrease in mean VAS scores when compared with Group 1 at both the one week and three month follow ups (P = 0.04, P = 0.03, respectively).

Conclusion:

Although topical desensitizer and Low Level Laser are both effective in reducing dentinal hypersensitivity, Low Level Lasers are comparatively more effective at the studied time intervals.

Keywords: Desensitizing agent, low-level laser therapy, randomized controlled trial, visual analog scale

INTRODUCTION

Dentin hypersensitivity is defined as “short, sharp pain arising from exposed dentin in response to stimuli typically thermal, evaporative, tactile, osmotic, or chemical and which cannot be ascribed to any other form of dental defect or pathology.” It is often referred to as the “common cold of dentistry,” due to its high prevalence which ranges from 2.8% to 74%.[1,2,3] When the protective enamel/cementum is lost, the dentinal tubules will be exposed to external stimuli and result in hypersensitivity. Among many theories proposed regarding the mechanism of dentin hypersensitivity, Brannstroms hydrodynamic theory is the most widely accepted theory, which states that external stimuli cause fluid movement inside the dentinal tubules either in the inward or outward direction and promote mechanical deformation of nerve endings at the pulp/dentin. It will be transmitted as a painful sensation.[4]

Based on the Brannstroms hydrodynamic theory, the two chief methods of treating dentin hypersensitivity are tubular occlusion and blockage of nerve activity.[5] Popularly, topical desensitizing agents such as glutaraldehyde, resin-based desensitizing solutions, and fluoride varnishes are used to treat dentinal hypersensitivity, which occludes the tubules by cross-linking of dentinal proteins.

The advent of dental lasers has given us an interesting treatment option for dentinal hypersensitivity and has become a research interest in the last decade. The middle output power lasers such as ND:YAG lasers and CO2 lasers have enjoyed significant success in treating this condition. However, they are very expensive and bulky to lug around. Low-level lasers such as He-Ne lasers and GaAlAs lasers are relatively unexplored in dentistry.[6] The low-level or “soft” lasers provide low-energy emissions with little temperature increase of <0.1°C. These wavelengths are believed to stimulate circulation and cellular activity and to provide various effects such as anti-inflammatory, vascular, analgesic, and tissue healing.[7] According to physiological experiments using the GaAlAs laser at 830 nm, analgesic effect is caused by blocking the depolarization of C-fiber afferents. Some studies have compared middle output power lasers with low-level lasers, and the results were inconsistent.[8,9] Very few studies have compared the 904 nm diode laser with topical desensitizing agents on dentinal hypersensitivity. In the studies conducted the results were controversial, or the appropriate study design which is a randomized controlled trial was not used. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there are no clinical trials comparing the desensitizing efficacy of a low-level diode laser with glutaraldehyde-based topical desensitizing agents.

Hence, the aim of this study is to compare the clinical effectiveness of low-level diode laser and glutaraldehyde-based topical desensitizing agent on cervical dentin hypersensitivity with the help of visual analog scale (VAS).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Before the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. In addition, written consent from the patients was also obtained. The present double-blinded randomized controlled trial included patients in the age group of 20–50 years, visiting the Outpatient Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics with cervical dentinal hypersensitivity.

Inclusion criteria

Dentinal hypersensitivity caused by gingival recession or cervical abrasion/erosion

Preoperative VAS score of ≥2

Systemic health of the patient is good

Minimum two teeth present in two different quadrants were included (for eg: 16 and 26).

Exclusion criteria

Teeth with caries, defective restorations, occlusal restorations, and chipped teeth

Deep periodontal pockets (probing depth >6 mm), periodontal surgery within the previous 3 months, and subjects with orthodontic appliances or bridge work

Cervical defect >2 mm horizontally[10]

Use of desensitizing toothpaste in the last 3 months

Patients allergic to ingredients used in the study

Any gross oral pathology

Systemic diseases such as eating disorders, chronic diseases, pregnancy and lactation, acute myocardial infarction within the past 6 months, use of pacemaker, uncontrolled metabolic disease, major psychiatric disorder, heavy smoking, or alcohol abuse.

Sample size determination

The sample size was estimated based on the data obtained from a previous study.[11]

The pooled standard deviation (S) and mean expected difference (d) were obtained from the same article.

Considering pooled standard deviation (S) = 1.4 cm with mean expected difference (d) = 1 cm, the sample size was estimated to be 21 per group. The sample size was increased by 15% to adjust for any loss to follow-up. Hence, the final sample size is 25 per arm.

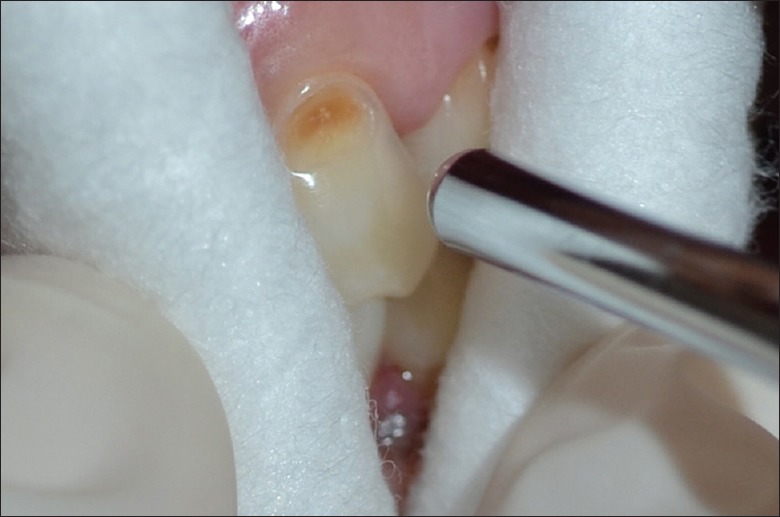

Diagnosis was made based on the patient's history, clinical examination, and pulp vitality tests. To assess tooth sensitivity, a controlled air stimulus (evaporative stimulus) and cold water (thermal stimulus) were used. Sensitivity was measured using a 10-cm VAS score, with a score of zero being a pain-free response and a score of 10 being excruciating pain or discomfort. Scoring of tooth sensitivity was done using controlled air pressure from a standard three-way dental syringe on a fixed dental chair at 40–65 psi at ambient temperature, directed perpendicularly and at a distance of 1–3 mm from the exposed dentin surface, while adjacent teeth were protected with cotton rolls to prevent false-positive results [Figure 1]. This was followed by scoring of tooth sensitivity using 10 ml of ice-cold water applied to the exposed dentin surface, while neighboring teeth were isolated during testing using the operator's fingers and cotton rolls. A period of at least 5 min was allowed between the two stimuli on each tooth.

Figure 1.

Controlled air stimulus (evaporative stimulus) 1–3 mm from the tooth surface

Hence, for the 50 teeth that were included in the study, the first scores (baseline) were recorded and the subjects were randomly assigned to one of the treatment groups by coin flip technique. The group allocation was done by a neutral operator to overcome selection bias. Following which, the teeth were assigned either one of the following treatments – topical desensitizing therapy or laser therapy to either left or right side of the arch.

Group 1: Glutaraldehyde-based topical desensitizing agent (Heraeus Kulzer, Germany)

Group 2: Low-level diode laser (904 nm) (QuantaPulse Pro 904 nm – Superpulsed, Rikta, Kvantmed, Russia).

For Group 1, the glutaraldehyde desensitizer was manipulated according to the manufacturer's instructions and painted with a disposable brush at cervical region, after which the laser delivery tip was placed without activation [Figure 2]. The patients were instructed not to eat for 1 h following the desensitizer application.

Figure 2.

LASER probe with only red LED light-activated (placebo)

Moreover, in Group 2, the cervical area was irradiated with a low-level GaAlAs laser, emitting a 904 nm wavelength. The cone tip (beam converging) was used as close as possible with the tooth surface without contact, resulting in a spot size of 0.8 cm2. Laser beam was directed perpendicular to tooth surface at three points: one apical and two cervical points (one mesiobuccal and one distobuccal). Each area was irradiated for 1 min (total of 3 min per tooth). With an average power output of 60 mW at 4000 Hz, 9 J/cm2 of fluence was received by each tooth.

After recording sensitivity scores at baseline, patients were advised to use the toothpaste with soft bristle tooth brushing twice a day. Patients were directed to refrain from any other dentifrice or mouth rinse during the trial but were allowed to continue their normal oral hygiene practice. The sensitivity scores were recorded, immediately and 1 week and 3 months after the therapy by the blinded patients, which were then evaluated by a neutral blinded evaluator.

Statistical considerations

Normality of the data distribution was checked using Shapiro–Wilk test. Since nonnormal distribution was attained, nonparametric tests were used. For the comparison between two groups at any given time interval, Mann–Whitney U-test was used. For within-group comparison, Friedman's test was used.

RESULTS

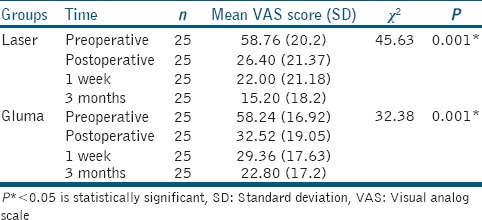

Of the 212 patients screened, 23 patients (50 teeth) were recruited for the study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The pain scores for both groups were recorded, and both intra- and inter-group comparisons were done. The mean VAS scores for Group 1 recorded were 58.24 (16.92), 32.52 (19.05), 29.36 (17.63), and 22.80 (17.2) at baseline, immediate postoperatively, 1-week postoperatively, and 3-month postoperatively, respectively. For Group 2, the scores were 58.76 (20.2), 26.40 (21.37), 22.00 (21.18), and 15.20 (18.2). There was a significant reduction in pain in both the groups over the evaluation period of 3 months (P = 0.001) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Intragroup comparison of pain over time period for thermal stimuli

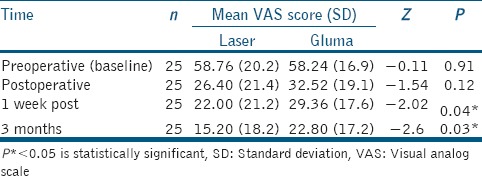

Intergroup comparison of baseline or preoperative VAS scores shows no significant difference between Group 1 and Group 2 (P = 0.91). Similarly, immediate postoperative VAS scores show no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.12) although both the groups have shown reduction in the pain scores compared to baseline. At 1-week and 3-month follow-up, a significant difference in mean VAS score was observed between the two groups, with the Group 2 showing a greater reduction compared to Group 1 (P = 0.04, P = 0.03, respectively) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Intergroup comparison of pain

DISCUSSION

Despite the available traditional methods, dentin hypersensitivity remains a chronic dental problem with a different treatment conduct and an uncertain prognosis. Pain resulting from dentin hypersensitivity can be treated by blocking the nerve endings of odontoblastic process and by occluding or narrowing of the dentinal tubules, thereby reducing the fluid movement inside the dentinal canaliculi.[4] The traditional method for treating dentin hypersensitivity is based on the application of topical desensitizing agents. However, it has some disadvantages such as repeated application, longer treatment time, and patient compliance. Use of newer treatment modalities for hypersensitivity such as LASERs has increased rapidly in the last two decades.[4,5]

Although low-level lasers and glutaraldehyde-based topical desensitizing agents present distinct modes of action in the present study, both treatments provided a significant overall relief in dentin hypersensitivity. Most experimental and clinical studies regarding the effectiveness of low-level laser therapy on dentin hypersensitivity were performed using semiconductor diode lasers with wavelengths in the range of 635–830 nm and dosages in the range of 2–10 J/cm. None of these laser outputs have shown to cause any physical changes or damage to dentin. However, a small fraction of the laser energy at 830 nm wavelength is transmitted through dental hard tissues to reach the pulp. Similarly, the 904 nm wavelength used in this study showed no clinical changes in dentin and reduced the dentinal hypersensitivity immediately, 1 week after and 3 months after the first application.

Low-power laser therapy generally promotes biomodulatory effects, minimizes pain, and reduces inflammatory processes. However, their ability to block depolarization of nerve fibers and depress neural transmission seems to play a major role in reducing dentin hypersensitivity. When applied with a sufficient level of intensity, it causes an inhibition of action potentials by forming reversible varicosities (bending of axons) where there is an approximately 30% neural blockade within 10–20 min of application.[12] Although precise mechanism of action is unknown, GaAlAs laser emissions at 904 nm have a definite analgesic effect.[8]

Besides its immediate analgesic effect, if laser is used within the correct parameters, it will stimulate the normal physiological cellular functions. Therefore, at subsequent appointments, the pulpal tissue would be less injured and inflamed and the laser would stimulate the production of sclerotic dentin, thus promoting the internal obliteration of dentinal tubules. This could explain the extended reduction in pain scores at 1 week and 3 months after the first dose.

On the other hand, it has been indicated that desensitizing agents containing glutaraldehyde and HEMA, such as Gluma, kill bacteria and coagulate plasma proteins within the dentinal fluids, forming a coagulation plug and thus reduce hypersensitivity. Its effect lasts up to 9 months. They also have a positive effect on the resin-dentin bonding. Hence, it has been employed as the positive control in this study. Similar results have been obtained in this study, where Gluma has shown significant reduction in pain scores at the end of 3 months.

Regardless of the method and materials employed, the evaluation of treatments for dentin hypersensitivity is not simple. In estimating treatment effects on hypersensitive teeth, investigations may be handicapped by the difficulty to assess patient's response objectively and are dependent upon the patient's interpretation, which is in turn subjected to suggestion. Dentinal hypersensitivity may differ for different stimuli, and it is recommended by Holland et al.[13] that at least two hydrodynamic stimuli should be used, as in this study.

Furthermore, placebo effect has been described in clinical dentin hypersensitivity trials (Wilder-Smith, 1988). In the present investigation, the possibility of a placebo effect was reduced by placing the laser tip without activating it (only LED lights were switched on) on the sites receiving the control medication (Gluma group). Furthermore, the sites receiving the laser irradiation was rubbed with saline using a microbrush. In this study, the reduction in immediate postoperative pain was almost similar for both the groups (P = 0.12), which could suggest that placebo did not play an influential role.

For more effective treatment, further investigation is required to increase the understanding of the mechanisms and etiology of dentinal pain. The findings that revealed by both laboratory and clinical research are extremely important to support the development or improvement of therapies that may acutely contribute to the treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity sufferers.

CONCLUSION

Based on the findings of this clinical evaluation, it may be concluded that low-level GaAlAs laser and Gluma topical desensitizer showed similar immediate decrease in cervical dentin hypersensitivity. Low-level laser showed improved results at 1-week and 3-month intervals compared to the topical agent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taani SD, Awartani F. Clinical evaluation of cervical dentin sensitivity (CDS) in patients attending general dental clinics (GDC) and periodontal specialty clinics (PSC) J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:118–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees JS, Addy M. A cross-sectional study of buccal cervical sensitivity in UK general dental practice and a summary review of prevalence studies. Int J Dent Hyg. 2004;2:64–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5029.2004.00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu HC, Lan WH, Hsieh CC. Prevalence and distribution of cervical dentin hypersensitivity in a population in Taipei, Taiwan. J Endod. 1998;24:45–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(98)80213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yilmaz HG, Kurtulmus-Yilmaz S, Cengiz E, Bayindir H, Aykac Y. Clinical evaluation of Er, Cr: YSGG and GaAlAs laser therapy for treating dentine hypersensitivity: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Dent. 2011;39:249–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trushkowsky RD, Oquendo A. Treatment of dentin hypersensitivity. Dent Clin North Am. 2011;55:599–608, x. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corona SA, Nascimento TN, Catirse AB, Lizarelli RF, Dinelli W, Palma-Dibb RG, et al. Clinical evaluation of low-level laser therapy and fluoride varnish for treating cervical dentinal hypersensitivity. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:1183–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2003.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerschman JA, Ruben J, Gebart-Eaglemont J. Low level laser therapy for dentinal tooth hypersensitivity. Aust Dent J. 1994;39:353–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1994.tb03105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimura Y, Wilder-Smith P, Yonaga K, Matsumoto K. Treatment of dentine hypersensitivity by lasers: A review. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:715–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027010715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flecha OD, Azevedo CG, Matos FR, Vieira-Barbosa NM, Ramos-Jorge ML, Gonçalves PF, et al. Cyanoacrylate versus laser in the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity: A controlled, randomized, double-masked and non-inferiority clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2013;84:287–94. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.120165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen EP. Noncarious cervical lesions: Graft or restore? J Esthet Restor Dent. 2005;17:332–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2005.tb00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yilmaz HG, Kurtulmus-Yilmaz S, Cengiz E. Long-term effect of diode laser irradiation compared to sodium fluoride varnish in the treatment of dentine hypersensitivity in periodontal maintenance patients: A randomized controlled clinical study. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29:721–5. doi: 10.1089/pho.2010.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotler HB, Chow RT, Hamblin MR, Carroll J. The use of low level laser therapy (LLLT) for musculoskeletal pain. MOJ Orthop Rheumatol. 2015;2:pii: 00068. doi: 10.15406/mojor.2015.02.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland GR, Narhi MN, Addy M, Gangarosa L, Orchardson R. Guidelines for the design and conduct of clinical trials on dentine hypersensitivity. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:808–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]