Abstract

Objective

To determine the association between ruptured saccular aneurysms and aspirin use/aspirin dose.

Methods

Four thousand seven hundred one patients who were diagnosed at the Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women's Hospital between 1990 and 2016 with 6,411 unruptured and ruptured saccular intracranial aneurysms were evaluated. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the association between aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and aspirin use, including aspirin dose. Inverse probability weighting using propensity scores was used to adjust for potential differences in baseline characteristics between cases and controls. Additional analyses were performed to examine the association of aspirin use and rerupture before treatment.

Results

In multivariate analysis with propensity score weighting, aspirin use (odds ratio [OR] 0.60, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.45–0.80) was significantly associated with decreased risk of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. There was a significant inverse dose-response relationship between aspirin dose and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.53–0.81). In contrast, there was a significant association between aspirin use and increased risk of rerupture before treatment (OR 8.15, 95% CI 2.22–30.0).

Conclusions

In this large case-control study, aspirin therapy at diagnosis was associated with a significantly decreased risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage, with an inverse dose-response relationship among aspirin users. However, once rupture has occurred, aspirin is associated with an increased risk of rerupture before treatment.

Despite endovascular and microsurgical advances in early intervention of ruptured and unruptured aneurysms, noninvasive measures for aneurysm prevention, stabilization, and regression are yet to be identified.1 Because inflammation is thought to play a key role in the pathogenesis of intracranial aneurysm rupture, antiplatelet agents and, in particular, aspirin have emerged as possible candidates for noninvasive treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Recently, the International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms (ISUIA) investigators reported that patients who used aspirin at least 3 times weekly had significantly lower risks of aneurysm rupture than those who never use aspirin, suggesting that frequent aspirin use may have a protective effect.2 Accordingly, we recently demonstrated in a group of 747 patients with intracranial aneurysms that patients taking aspirin had a significantly lower rate of hemorrhagic presentation compared with nonusers.3 However, there is conflicting evidence of the role of aspirin in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH). A recent meta-analysis of 7 studies suggests an increased risk of aSAH among short-term (<3 months) aspirin users.4 However, the studies included had significant heterogeneity. Here, we present the largest single-institution study to date investigating the relationship between antiplatelet therapy, including aspirin dose, and intracranial aneurysm rupture in a case-control study of 4,701 patients harboring 6,411 intracranial aneurysms.

Methods

Using a combination of machine learning algorithms and manual medical chart review, we evaluated 4,701 patients who were diagnosed with an intracranial aneurysm between 1990 and 2016 at the Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital. We identified patients both prospectively on clinical presentation (2007–2016) and retrospectively using natural language processing in conjunction with the Partners Healthcare Research Patients Data Registry, which includes 4.2 million patients who have received care from Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital (1990–2013).5 Using ICD-9 and Current Procedural Terminology codes, we obtained an initial set of potential patients with aneurysm from the Research Patients Data Registry, and we then used natural language processing to train a classification algorithm that yielded 5,589 patients. Of these patients, 727 were also seen on clinical presentation from 2007 to 2013 with prospectively collected data. We included 474 additional patients with prospectively collected data who were seen on clinical presentation from 2013 to 2016. We then reviewed the medical records and imaging studies of the 6,063 patients in detail (A.C. and R.D.) to ultimately identify 4,701 patients with definite saccular aneurysms. We recorded the results of the imaging studies, including intracranial aneurysm site and size, and excluded patients with possible infundibula or nondefinitive diagnoses of aneurysms, feeding artery aneurysms associated with arteriovenous malformations, and fusiform or dissecting aneurysms, as well as those lacking clinical notes or radiographic images. In addition, we excluded patients who received treatment of their aneurysm(s) before presentation. We categorized patients who presented with an aSAH as harboring a ruptured aneurysm.

We obtained information on patient characteristics, including age, sex, and race, and comorbid conditions, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation. We also noted the number and maximum size of intracranial aneurysms, antihypertensive medication use, family history of aneurysms or SAH, and information on current tobacco and alcohol use. The diagnosis of aSAH was confirmed with a CT scan, with CSF analysis, or intraoperatively by a neurosurgeon. In addition, we collected detailed data on antiplatelet therapy, type of antiplatelet agent, and aspirin dose at the time of diagnosis of the intracranial aneurysms. A risk factor was assumed to be absent if we found no documentation of its presence. We obtained clinical notes with antiplatelet medication details by using the following search terms: antiplatelet, ASA, acetylsalicylic, aspirin, clopidogrel, plavix, prasugrel, ticlopidine, ticlid, ticagrelor, brilinta, cilostazol, pletal, vorapaxar, zontivity, abciximab, reopro, eptifabatide, integrilin, tirofiban, aggrastat, persantine, dipyridamole, and aggrenox. These clinical notes were subsequently manually reviewed.

Differences in baseline characteristics between antiplatelet therapy and no antiplatelet therapy groups were evaluated with t tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were implemented to test for effects due to aspirin use (excluding patients on dual antiplatelet agents or nonaspirin antiplatelet agents) and aspirin dose, with a backward elimination procedure to identify significant confounders. Cutoff values of p = 0.1 were used to select the initial set of variables to be included in the initial multivariable model for backward elimination. The resulting covariates were used for all subsequent multivariable analyses. To adjust for differences in baseline characteristics, propensity score weighting was applied using the same covariates as the unweighted model. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated, and values of p < 0.05 were considered significant. A sensitivity analysis including all antiplatelet agents was also performed. In addition, an analysis of the association between aspirin use and rerupture status before treatment was performed in the subgroup of patients with ruptured aneurysms. Because rerupture was a rare event, the Firth penalized-likelihood logistic regression was used to overcome the separation problem and sparse data bias. Missing values were accounted for by using multiple imputation with chained equations. Inferential statistics were obtained from 40 imputed datasets. Sensitivity analysis using a subgroup consisting of complete cases only was also performed. All statistical analyses were performed with the Stata statistical software package (version 14; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study.

Data availability

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator (data available from Dryad, table e-1, table e-2, table e-3, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s6k4b4j).

Results

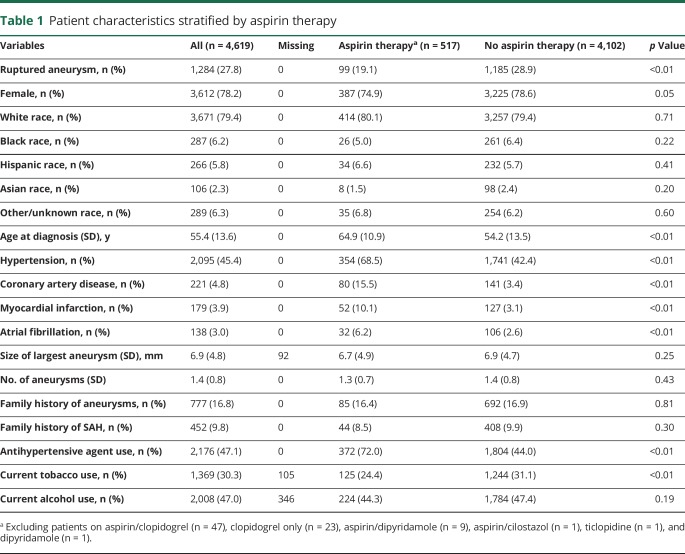

Patient demographics and characteristics stratified by aspirin therapy are shown in table 1 and by all antiplatelet therapy are shown in data available from Dryad (table e-1, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s6k4b4j). A total of 4,701 patients with 6,411 aneurysms were included, of which 1,302 (27.7%) were ruptured. Fife hundred ninety-nine (12.7%) patients were on current antiplatelet therapy and 517 were on aspirin only at the time of rupture or diagnosis of unruptured aneurysms. In general, patients on aspirin therapy were significantly older and less frequently diagnosed with ruptured aneurysms. In addition, patients on aspirin therapy were less likely to be current smokers but more likely to have hypertension, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation and more likely to be taking an antihypertensive agent.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics stratified by aspirin therapy

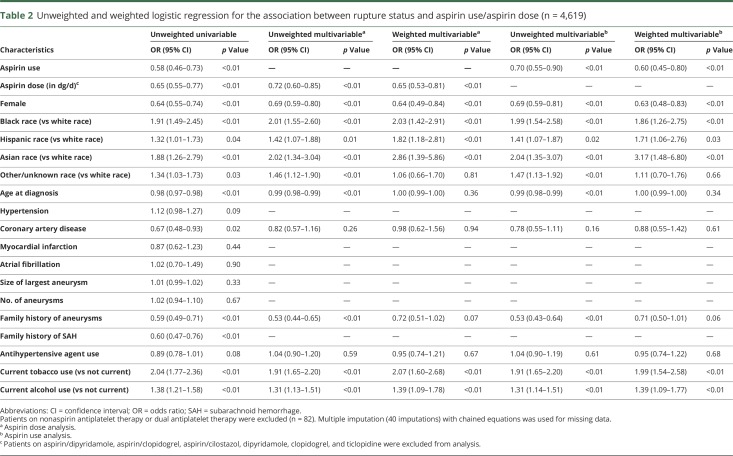

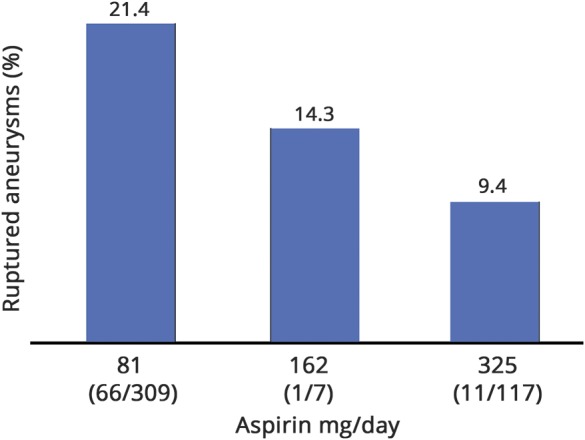

Table 2 shows the results of the unweighted and weighted multivariable analyses for aspirin use only and for aspirin dose, excluding patients on nonaspirin antiplatelet agents and dual antiplatelet medications. In weighted multivariable analysis for aspirin use, black race (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.42–2.91), Hispanic race (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.18–2.81), Asian race (OR 2.86, 95% CI 1.39–5.86), current alcohol use (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.60–2.68), and current tobacco use (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.09–1.78) were significantly associated with aSAH. In contrast, female sex (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.49–0.84) and aspirin therapy (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.53–0.81) were significantly associated with a lower rupture risk. Age, coronary artery disease, family history of aneurysms, and antihypertensive agent use were not significantly associated with rupture. A sensitivity analysis including all antiplatelet agents showed similar results (data available from Dryad, table e-2, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s6k4b4j). In an analysis of aspirin dose, higher aspirin dose was significantly associated with decreased risk of ruptured aneurysms (unweighted OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.60–0.85, weighted OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.53–0.81) (table 2). Table 3 and data available from Dryad (table e-3, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s6k4b4j) show the unweighted and weighted analyses of complete cases only, with similar ORs for aspirin/antiplatelet therapy and aspirin dose. The figure shows the proportion of ruptured aneurysms stratified according to daily aspirin dose among aspirin-only users.

Table 2.

Unweighted and weighted logistic regression for the association between rupture status and aspirin use/aspirin dose (n = 4,619)

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression for rupture status in complete cases for aspirin-only group (n = 4,174 for aspirin dose, n = 4,253 for aspirin use)

Figure. Percentage of ruptured aneurysms among aspirin-only users stratified according to dose per day.

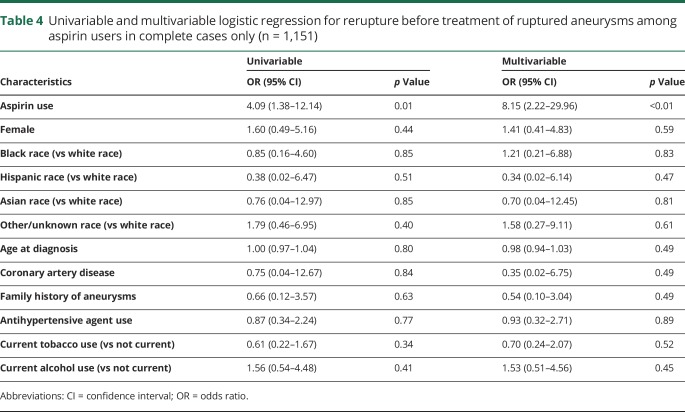

There were 17 cases of ruptured aneurysms that reruptured before initial treatment, 4 of whom were on aspirin at the time of rupture. Table 4 shows that aspirin therapy is significantly associated with increased risk of rerupture of untreated ruptured aneurysms (OR 8.15, 95% CI 2.22–30.0).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression for rerupture before treatment of ruptured aneurysms among aspirin users in complete cases only (n = 1,151)

Discussion

In this large case-control study, we show that antiplatelet therapy at diagnosis is associated with a markedly decreased risk of intracranial aneurysm rupture. In addition, there is an inverse dose-response relationship with aSAH among aspirin-only users. However, in ruptured aneurysms, aspirin use is associated with rerupture before treatment. The results of our study are in line with recently published smaller case-control and cohort studies on the effects of aspirin use on intracranial aneurysm rupture, supporting a potential protective effect of aspirin against aSAH.2,3,6 The exact mechanism by which aspirin may exert its preventive effects on aneurysm rupture is unclear. Recent studies have shown that aspirin (e.g., acetylsalicylic acid) may decrease the risk of aSAH by stabilizing aneurysm walls and counteracting proinflammatory pathways, which are thought to play a key role in propagating aneurysm wall weakening.1,7 Walls of ruptured human aneurysms have been reported to have higher levels of cyclooxygenase-2 and microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase 1, both of which are inhibited by aspirin.8

Several population-based studies have looked at the association between antiplatelet therapy and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), with conflicting results.4 Another study matched 58 patients with aSAH to 213 controls during a 5-year prospective follow-up study and was the first to report that patients who took aspirin at least 3 times a week had a lower risk of aSAH (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.11–0.67) compared with never takers.2 However, this effect was not seen in patients taking aspirin less frequently, and other antiplatelet agents were not included.2 Recently published results from a nationwide registry showed that aspirin use was significantly associated with an overall decreased risk of SAH (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67–1.00) but only among long-term users (>3 years) (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.45–0.90).6 No significant association was found for other antiplatelet agents.6 However, the control group consisted of people from the general population without unruptured aneurysms, and the number of aSAH was not specified. In a subsequent Danish nationwide case-control study (n = 5,834 SAH cases), the authors found no protective effect of long-term use (>3 months) of low-dose aspirin on SAH risk.9 In contrast, use of low-dose aspirin was associated with an increased risk of SAH in the first month after starting treatment.9 However, only low-dose (<150 mg/d) aspirin use was assessed, and the authors did not control for smoking status, one of the most important confounders of aSAH.9 Similar results were found by another Danish population–based study (n = 1,186 cases of first nontraumatic SAH), which showed that long-term dipyridamole and recent low-dose aspirin use were associated with rupture.10 However, lack of inclusion of smoking status in this study also could have limited the precision of the risk estimates.10 Although another population-based case-control study from the Netherlands (n = 1,004 SAH cases) showed an increase of SAH in patients on platelet aggregation inhibitors, the authors concluded that this finding was most likely due to residual confounding, and again, aSAH was not specified.11 The most important potential biases in all previously mentioned nationwide registries that rely on ICD-9 codes from computerized databases are misclassification of outcomes and reliance on redeemed prescriptions as a proxy for actual drug use.10 In addition, the use of computerized nationwide databases renders these studies vulnerable to potential confounders that are not covered by the databases such as smoking status, hypertension, and underlying conditions leading to antiplatelet therapy such as coronary artery disease.9,11

The major strength of our study is the large sample size in a uniformly organized system and a high-quality, detailed registry. Although our study provides sufficient statistical power to elucidate the association between aspirin/antiplatelet therapy and intracranial aneurysm rupture and to show a dose-response relationship, the study is limited by its partly retrospective nature. The reason for lower aspirin use in the ruptured group could be reporting bias in the setting of aSAH. However, the nonsignificant difference in the reporting of other medications such as antihypertensive medication use between patients with ruptured and unruptured aneurysms makes this bias less likely. In addition, propensity score weighting was used to control for selection bias. Our findings add to the growing body of evidence of the protective effects of aspirin against aneurysm rupture. In addition, as we and other authors have shown previously, aspirin use does not adversely affect presenting clinical grade, radiographic grade, vasospasm, and outcome in the setting of aSAH.3,12 In contrast, we recently showed that aspirin use was associated with a shorter hospital stay and lower rates of nonroutine discharge.13 Therefore, taking all evidence into account, we believe that antiplatelet agents could safely be continued in patients with incidentally found aneurysms. In addition, our study suggests that aspirin may be a promising simple and inexpensive candidate for prophylactic treatment of patients not already on antiplatelet therapy who are diagnosed with an unruptured aneurysm.

We found that aspirin therapy at diagnosis is associated with a decreased risk of SAH and that higher aspirin dose is significantly associated with decreased risk of rupture. However, once an aneurysm has ruptured, aspirin use is associated with increased risk of rerupture before initial treatment. Our findings, together with the results from other studies, suggest that aspirin should not be discontinued in patients on aspirin for other medical conditions. Whether aspirin should be instituted as a prophylactic measure in all patients with unruptured aneurysms requires a randomized controlled trial. In contrast, patients presenting with ruptured aneurysms may benefit from expeditious administration of platelets and/or treatment of the ruptured aneurysm to avoid rerupture.

Glossary

- aSAH

aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- CI

confidence interval

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision

- ISUIA

International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms

- OR

odds ratio

- SAH

subarachnoid hemorrhage

Author contributions

Anil Can: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Robert F. Rudy: acquisition of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Victor M. Castro: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Sheng Yu: analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Dmitriy Dligach, Sean Finan, Vivian Gainer, Nancy A. Shadick, Guergana Savova, and Shawn Murphy: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Tianxi Cai: analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Scott T. Weiss: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. Rose Du: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content.

Study funding

This study was supported by Partners Personalized Medicine (R.D.) and the NIH (U54 HG007963: T.C. and S.M.; U01 HG008685: S.M.; and R01 HG009174: S.M.).

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Starke RM, Chalouhi N, Ding D, Hasan DM. Potential role of aspirin in the prevention of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;39:332–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasan DM, Mahaney KB, Brown RD Jr, et al. Aspirin as a promising agent for decreasing incidence of cerebral aneurysm rupture. Stroke 2011;42:3156–3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross BA, Rosalind Lai PM, Frerichs KU, Du R. Aspirin and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg 2014;82:1127–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phan K, Moore JM, Griessenauer CJ, Ogilvy CS, Thomas AJ. Aspirin and risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2017;48:1210–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castro VM, Dligach D, Finan S, et al. Large-scale identification of patients with cerebral aneurysms using natural language processing. Neurology 2017;88:164–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Rodriguez LA, Gaist D, Morton J, Cookson C, Gonzalez-Perez A. Antithrombotic drugs and risk of hemorrhagic stroke in the general population. Neurology 2013;81:566–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasan DM, Chalouhi N, Jabbour P, et al. Evidence that acetylsalicylic acid attenuates inflammation in the walls of human cerebral aneurysms: preliminary results. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasan D, Hashimoto T, Kung D, Macdonald RL, Winn HR, Heistad D. Upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 (mPGES-1) in wall of ruptured human cerebral aneurysms: preliminary results. Stroke 2012;43:1964–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pottegard A, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Poulsen FR, Hallas J, Gaist D. Antithrombotic drugs and subarachnoid haemorrhage risk: a nationwide case-control study in Denmark. Thromb Haemost 2015;114:1064–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt M, Johansen MB, Lash TL, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Sorensen HT. Antiplatelet drugs and risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage: a population-based case-control study. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:1468–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risselada R, Straatman H, van Kooten F, et al. Platelet aggregation inhibitors, vitamin K antagonists and risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Thromb Haemost 2011;9:517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toussaint LG III, Friedman JA, Wijdicks EF, et al. Influence of aspirin on outcome following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2004;101:921–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dasenbrock HH, Yan SC, Gross BA, et al. The impact of aspirin and anticoagulant usage on outcomes after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a Nationwide Inpatient Sample analysis. J Neurosurg 2016:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator (data available from Dryad, table e-1, table e-2, table e-3, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.s6k4b4j).