Abstract

Virulent strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are often associated with an acquired cytotoxic protein, exoenzyme U (ExoU) that rapidly destroys the cell membranes of host cells by its phospholipase activity. Strains possessing the exoU gene are predominant in eye infections and are more resistant to antibiotics. Thus, it is essential to understand treatment options for these strains. Here, we have investigated the resistance profiles and genes associated with resistance for fluoroquinolone and beta-lactams. A total of 22 strains of P. aeruginosa from anterior eye infections, microbial keratitis (MK), and the lungs of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients were used. Based on whole genome sequencing, the prevalence of the exoU gene was 61.5% in MK isolates whereas none of the CF isolates possessed this gene. Overall, higher antibiotic resistance was observed in the isolates possessing exoU. Of the exoU strains, all except one were resistant to fluoroquinolones, 100% were resistant to beta-lactams. 75% had mutations in quinolone resistance determining regions (T81I gyrA and/or S87L parC) which correlated with fluoroquinolone resistance. In addition, exoU strains had mutations at K76Q, A110T, and V126E in ampC, Q155I and V356I in ampR and E114A, G283E, and M288R in mexR genes that are associated with higher beta-lactamase and efflux pump activities. In contrast, such mutations were not observed in the strains lacking exoU. The expression of the ampC gene increased by up to nine-fold in all eight exoU strains and the ampR was upregulated in seven exoU strains compared to PAO1. The expression of mexR gene was 1.4 to 3.6 fold lower in 75% of exoU strains. This study highlights the association between virulence traits and antibiotic resistance in pathogenic P. aeruginosa.

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections can be severe in people with a compromised immune system and impaired anatomical structures caused by, for example burns, cystic fibrosis or mechanical abrasions [1]. P. aeruginosa is a successful opportunistic pathogen in part due to its production of a diverse repertoire of pathogenic factors and its innate ability to evade the host immune system [2]. Treatment of P. aeruginosa infections can be challenging due to the inherent antibiotic resistance, where some studies have shown that half of the isolates from clinical infections were resistant to antibiotics [3]. Furthermore, reports on co-selection of antibiotic resistance and pathogenic factors indicate that antibiotic resistance may be a factor for the evolution of more virulent strains of P. aeruginosa or vice versa [4–13].

Many Gram-negative bacteria, including P. aeruginosa, possess type III secretion systems (TTSS), which they utilise to introduce virulence factors directly into host cells [14]. In P. aeruginosa, TTSS transports four secreted factors: ExoU, ExoS, ExoY and ExoT. However, all of these factors may not be common in all P. aeruginosa strains. For example, the exoS gene was present in 58–72%, the exoU gene in 28–42%, the exoY gene in 89% and the exoT gene in 92–100% of isolates from acute infections [15]. Pathogenic strains contain either exoU or exoS, but rarely both [16, 17]. The exoU gene is associated with a genomic island and its acquisition may cause loss of the exoS [18, 19]. The exoU gene encodes a cytotoxic protein that rapidly destroys the cell membranes of mammalian cells by its phospholipase activity [19]. The presence of exoU correlates with phenotypes that are responsible for the severe outcome of many infections including pneumonia [20] and keratitis [21]. Up to two-thirds of ocular isolates of P. aeruginosa possess the exoU gene [22], which is a much higher rate than the isolates from other infections [6, 23, 24].

The frequency of antibiotic resistance of the exoU gene carrying strains is higher than that of exoS-strains; [5, 10] the reason for this higher frequency remains undefined. P. aeruginosa strains with the exoU gene tend to harbour mutations in quinolone resistance determining regions (QRDRs) that lead to fluoroquinolone resistance [5, 9]. Whilst it is known that strains of P. aeruginosa can possess mutations in resistance determining regions affecting beta-latam susceptibility, such as the chromosomal beta-lactamase gene (ampC), its transcriptional regulator (ampR) [25] and a repressor gene (mexR) that negatively regulates expression of an active efflux pump (MexAB-OprM) [26], the correlation between the exoU carriage and mutations in drug resistance determining regions has not been extensively examined.

We hypothesised that possession of the exoU gene correlates with mutations not only in QRDRs but also in beta-lactam resistance determining regions. The aim of this study was to examine the correlation between the virulent genotypes (exoS vs. exoU) and resistance to beta-lactam and fluoroquinolone antibiotics in P. aeruginosa strains. Furthermore, we examined the relative expression of specific genes to confirm their role in antibiotic resistance.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates and antibiotic susceptibility testing

Twenty-two P. aeruginosa strains isolated from anterior eye infections, microbial keratitis (MK), or lungs of cystic fibrosis patients from India and Australia were used in this study (Table 1). The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of ceftazidime (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA), cefepime (European Pharmacopoeia, Strasbourg, France) aztreonam (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc), ticarcillin (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc), imipenem (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc), levofloxacin (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc), ciprofloxacin (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc), and moxifloxacin (European Pharmacopoeia) were determined by the broth microdilution method as described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [27]. The MIC was taken as the lowest concentration of an antibiotic in which no noticeable growth (turbidity) was observed [28] and the break point was established according to published standards [29, 30]. Both resistant and intermediate resistant strains were considered here as resistant.

Table 1. Strains and origin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa used in this study.

| Isolate designation | Origin | Associated infections |

|---|---|---|

| PA17 | Australia | MK |

| PA149 | Australia | MK |

| PA157 | Australia | MK |

| PA171 | Australia | MK |

| PA175 | Australia | MK |

| PA40 | Australia | MK |

| PA32 | India | MK |

| PA33 | India | MK |

| PA34 | India | MK |

| PA35 | India | MK |

| PA37 | India | MK |

| PA82 | India | MK |

| PA55 | Australia | CF |

| PA57 | Australia | CF |

| PA59 | Australia | CF |

| PA64 | Australia | CF |

| PA66 | Australia | CF |

| PA86 | Australia | CF |

| PA92 | Australia | CF |

| PA100 | Australia | CF |

| PA102 | Australia | CF |

| PAO1 | Reference strain [64] (RefSeq accession no. NC_002516.2) |

MK = Microbial keratitis, CF = Cystic fibrosis

DNA extraction and sequencing

Bacterial DNA was extracted from overnight cultures grown on Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA; Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK), using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was sequenced on MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) platform generating 300 bp paired-end reads. The paired-end library was prepared using Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). All of the libraries were multiplexed on one MiSeq run. Genome assembly and annotations were performed using SPAdes version 3.11.1 [31] and Prokka version 1.7 [32]. BLAST search was performed to investigate carriage of exoU and exoS genes. All nucleotide sequences were deposited in NCBI GenBank data base under Bio-project accession number PRJNA431326.

Sequence analysis and variant calling

The mutations in selected resistance genes (gyrA, gryB, parC, parE, mexR, ampC, ampD and ampR) of each strain were determined with reference to P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Genbank RefSeq accession no. NC_002516.2). Briefly, the reference genome was mapped to the paired-end reads for each isolate using Bowtie2 version 2.3.2 [33] and the variants were compiled and annotated using SAMtools, version 1.7 [34] and SnpEff version 4.3 [35]. The QRDRs were assigned to amino acid positions 83 to 87 of the GyrA protein, positions 429 to 585 of the GyrB protein, positions 82 to 84 of the ParC protein, and positions 357 to 503 of the ParE protein [36]. For ampC variants, mutations different from common polymorphisms (G27D, R79Q, T105A, Q156R, L176R, V205L, and G391A), which are present in both susceptible and non-susceptible strains [37] were considered here. Mutations in mexR or ampR were considered as significant for resistance from previous literature [38–40].

Total RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis

Strains were revived from frozen stocks into 5 mL Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB; Oxoid) and grown to mid-exponential phase (OD660 1.5) and 1 ml was centrifuged at 6000 g for 3 min to harvest the cells. The pellet was mixed with 1 mg/ml lysozyme in Tris-EDTA buffer (TE; 10 mM Tris-hydrochloride and 1.0 mM EDTA pH 8.0) to lyse the cells. RNA extraction was performed using the ISOLATE RNA Mini Kit (Bioline, London, UK) following the manufacturer instructions for RNA isolation from bacteria. The RNA extract was treated with DNase1 (Bioline) to eliminate the DNA contamination and purified by ethanol precipitation [41]. RNA purity and concentration was measured by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000, ThermoFisher, MA, USA). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using SuperScript First-Strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) employing random primers and following the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR was performed with a PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX, USA), using 96 well optical plates (MicroAmp Fast Optical, Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions and cycle conditions. A 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) was used to measure the expression levels of the target DNA sequences using gene specific primers (Table 2). The relative expression levels were quantified using the comparative CT method [42] to obtain the fold change in each gene with reference to the respective genes of P. aeruginosa PAO1, which does not carry the exoU gene. A house keeping gene, rpsL encoding the 30S ribosomal protein S12, was used as an internal expression control for normalisation. The experiments were carried out three times in triplicate and the mean and standard deviations were calculated.

Table 2. Primers used in this study.

| Genes | Functions | Primers (5–3) | Length (bp) | Nucleotide position in gene | Product length (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ampC | Cephalosporinase | CGGCTCGGTGAGCAAGACCTTC–F | 22 | 264 | 218 | [46] |

| AGTCGCGGATCTGTGCCTGGTC–R | 22 | 481 | ||||

| mexR | Transcriptional regulator | CGCGAGCTGGAGGGAAGAAACC–F | 22 | 217 | 150 | [46] |

| CGGGGCAAACAACTCGTCATGC–R | 22 | 366 | ||||

| ampR | Transcriptional regulator | TGCTGTGTGACTCCTTCGAC–F | 20 | 215 | 160 | This Study |

| AGATCGATGAAGGGATGGCG–R | 20 | 374 | ||||

| rpsL | 30S ribosomal protein S12 (house keeping gene) | GCAAGCGCATGGTCGACAAGA–F | 21 | 35 | 201 | [46] |

| CGCTGTGCTCTTGCAGGTTGTGA–R | 23 | 235 |

Results

Possession of exoU/exoS and antibiotic resistance

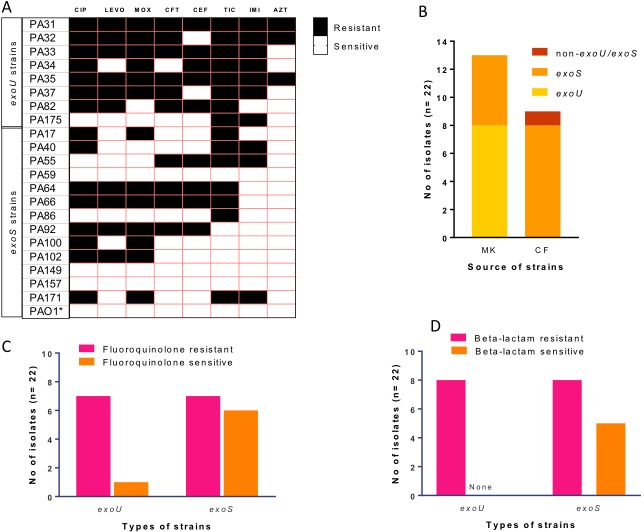

BLAST search showed that of the 22 isolates, 8 out of the 13 eye isolates (62%) possessed the exoU gene, while it was absent from the cystic fibrosis (CF) isolates (Fig 1B). Except for a CF strain (PA57) which lacked both exoU and exoS genes, all strains that lacked the exoU gene carried the exoS gene and none of the studied strains harboured both genes. For the exoS strains, 8/13 showed a medium level (2–16 μg/ml) of resistance to at least one fluoroquinolone and 8/13 were resistant to at least one beta-lactam, mostly ticarcillin (Fig 1A). Six of these eight strains were resistant to both a fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam. All except one (PA175) exoU strain were resistant to at least two tested fluoroquinolones with MICs of between 2–128 μg/ml with six strains having ≥32 for ciprofloxacin. All the exoU strains were resistant to at least three beta-lactams except for PA175, which was only resistant to ticarcillin and imipenem (Fig 1B, 1C and 1D).

Fig 1. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns and possesion of exoU and exoS genes.

A) Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of exoU and exoS strains. Both resistant and intermediate resistant strains were considered here as resistant. Black boxes represent resistance and white boxes represent susceptibility. B) Number of microbial keratitis (MK) and cystic fibrosis (CF) isolates that carry exoU or exoS genes. C) susceptibility of exoU and exoS strains to fluoroquinolones. D) susceptibility of exoU and exoS strains and to beta-lactams. [CIP = ciprofloxacin, LEVO = Levofloxacin, MOX = Moxifloxacin, CFT = ceftazidime, CEF = cefepime, TIC = ticarcillin, IMI = imipenem, AZT = Aztreonam].

Mutations in target genes of QRDRs and possession of exoU

Mutations in four different QRDRs were examined with reference to P. aeruginosa PAO1. Of the strains containing exoU, 6/8 had a T83I mutation in gyrA and 5/8 had combined mutations in both gyrA (T83I) and parC (S87L); none of the exoS strains had either of these mutations. Strains with mutations in gyrA or parC were resistant to all three fluoroquinolones and these mutations correlated with higher MICs for fluoroquinolones (Table 3). None of the exoS strains possessed mutations in gyrA and parC. However, mutations were observed in gyrB and parE in five exoS-strains which were associated with higher MIC to fluoroquinolones (Table 3). Interestingly, no mutations in gyrB or parE were found in the exoU strains. It should be noted that five strains (PA82, PA17, PA40, PA100 and PA171) had no mutations in any of these genes, but were resistant to at least one fluoroquinolone, although resistance tended to be ≤8 μg/ml, except PA82 which had an MIC of 64 μg/ml for ciprofloxacin.

Table 3. Mutations in the quinolone resistance determining region of P. aeruginosa and the MIC of fluoroquinolones.

| Strain | Genes | MIC (μg/ml) of Fluoroquinolones | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gyrA | gryB | parC | parE | CIP | LEVO | MOX | ||

| exoU strains | PA31 | T83I | S87L | 32 | 32 | 64 | ||

| PA32 | T83I | S87L | 64 | 32 | 128 | |||

| PA33 | T83I | S87L | 128 | 32 | 64 | |||

| PA34 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |||||

| PA35 | T83I | S87L | 64 | 32 | 128 | |||

| PA37 | T83I | S87L | 64 | 32 | 128 | |||

| PA82 | 64 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| PA175 | T83I | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | ||||

| exoS strains | PA17 | 2 | 1 | 8 | ||||

| PA40 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| PA55 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | |||||

| PA59 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 1 | |||||

| PA64 | A473V | 8 | 16 | 16 | ||||

| PA66 | E468D | 2 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| PA86 | L457-458A* | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| PA92 | S466F | A473V | 4 | 4 | 16 | |||

| PA100 | 2 | 1 | 8 | |||||

| PA102 | A473V | 2 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| PA149 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | |||||

| PA157 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 | |||||

| PA171 | 4 | 2 | 8 | |||||

| PAO1** | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | |||||

The numbers denote change in amino acid positions when compared with the genome of P. aeruginosa PAO1.

Bold = resistant or intermediate resistant.

CIP = ciprofloxacin, LEVO = Levofloxacin, MOX = Moxifloxacin.

*Insertion and frameshift variant.

** Reference strain

Mutations associated with beta-lactam antibiotics and exoU

This study also examined mutations in cephalosporinase (ampC) and its regulator (ampR) and the efflux pump MexAB-OprM regulator (mexR). A number of mutations were seen in ampC, but only those mutations that have been previously reported to be significant contributors to resistance were considered here (all observed mutations are shown in S1 Table). Variation in amino acid position V356I was common in six exoU strains, Q155R was found in strain PA82 and no significant mutations were observed in PA34. Such mutations were, however absent in exoS-strains. Similarly, all of the exoU strains had a common mutation in the in mexR gene at amino acid position 126, changing valine to glutamic acid, in addition to mutations at A110T in PA34 and K76Q in PA175. Such mutations were not present in the exoS strains. Furthermore, all the exoU strains had various mutations (E114A, G283E, and M288R) in the ampR gene, but only one exoS strain (PA171) had mutations in this gene and this at position 244. The susceptibility results showed that possession of such mutations was associated with higher MICs to various beta-lactams, except for strain PA175 which had all these mutations in mexR, ampC, and ampR genes but was sensitive to cefepime and ceftazidime (Table 4).

Table 4. Mutations in beta-lactam resistance determining regions and beta lactam resistance profiles.

| Strains | Genes | MIC (μg/ml) towards beta-lactams | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mexR | ampC | ampR | CFT | CEF | TIC | IMI | AZT | |||

| exoU strains | PA31 | V126E | V356I | G283E, M288R | 16 | 16 | 64 | 4 | 16 | |

| PA32 | V126E | V356I | G283E, M288R | 16 | 8 | 64 | 4 | 32 | ||

| PA33 | V126E | V356I | G283E, M288R | 32 | 16 | 128 | 8 | 8 | ||

| PA34 | A110T, V126E | E114A, G283E, M288R | 4 | 32 | >128 | 16 | 8 | |||

| PA35 | V126E | V356I | G283E, M288R | 16 | 32 | 128 | 8 | 16 | ||

| PA37 | V126E | V356I | G283E, M288R | 16 | 8 | 64 | 4 | 8 | ||

| PA82 | V126E | Q155I | G283E | >128 | >128 | 32 | 1 | 8 | ||

| PA175 | K76Q, V126E | V356I | G283E, M288R | 2 | 4 | 64 | 4 | 8 | ||

| exoS strains | PA17 | 4 | 4 | 128 | 1 | 8 | ||||

| PA40 | 1 | 2 | 64 | 4 | 8 | |||||

| PA55 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 4 | 8 | |||||

| PA59 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 8 | |||||

| PA64 | 16 | 64 | 32 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| PA66 | 16 | 64 | 32 | 0.25 | 8 | |||||

| PA86 | 4 | 8 | 64 | 1 | 8 | |||||

| PA92 | 32 | 64 | 8 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| PA100 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 0.5 | |||||

| PA102 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 0.5 | 4 | |||||

| PA149 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| PA157 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| PA171 | R244W | 2 | 1 | 32 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| PAO1** | 1 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 4 | |||||

The numbers denote change in amino acid positions when compared with the genome of P. aeruginosa PAO1.

Bold = resistance or intermediate resistance.

CFT = ceftazidime, CEF = cefepime, TIC = ticarcillin, IMI = imipenem, AZT = Aztreonam.

**Reference strain

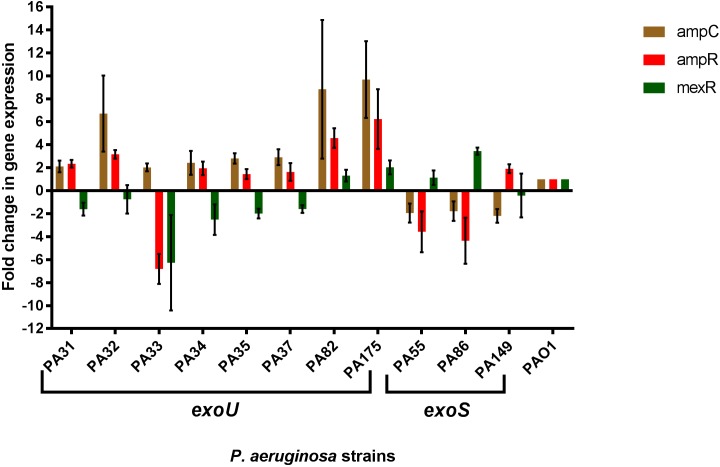

Expression analysis of ampC, ampR and mexR genes

The relative expression of ampC, ampR and mexR genes in all of the exoU strains and three randomly selected exoS strains (PA55, PA86 and PA149) were compared to P. aeruginosa PAO1 to analyse the effect of such mutations on expression (Fig 2). The relative expression of the ampC was two to nine fold higher in all of the exoU strains and was slightly lower in all three exoS strains compared to PAO1. Similarly, the relative expression of the ampR was at least two fold higher for five out of eight exoU strains. For an exoU strain (PA33), the ampR gene was repressed six fold. The expression of mexR gene was repressed in six exoU strains while overexpression of mexR was observed in two exoS strains relative to PAO1.

Fig 2. Expression of cephalosporinase (ampC) its regulator (ampR) and the efflux pump MexAB-OprM regulator (mexR) in strains.

The relative expression levels were compared to Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (widetype, non-exoU strain) and are presented as fold change in gene expression. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean fold change.

Discussion

The exoU gene is commonly found in P. aeruginosa strains isolated from contact lens-related microbial keratitis, at frequencies of 46–54%, [11] whereas it only occurs in 0–14% of non-ocular isolates [6, 22–24]. Similar to a previous report, [10] exoU+ strains in the current study had higher resistance to beta-lactams than exoS+ strains (100% exoU strains vs. 61% exoS strains were resistant to at least one beta-lactam). ExoU secreting P. aeruginosa had more mutations in genes that are associated with beta-lactam resistance (mexR, ampC and ampR) than did exoS+ strains. Gene expression analysis suggested that such mutations generally lead to antibiotic resistance, as the expression of ampC and ampR generally increased while the expression of mexR was decreased, compared to the sensitive strain PAO1.

Several in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that the exoU carrying P. aeruginosa is associated with severe outcome of diseases [7, 12, 20, 21, 43, 44]. In additions, results of this and other studies confirmed that exoS+ and exoU+ strains have different antibiotic resistance patterns [10, 45]. Therefore, they may require different treatment strategies. Knowing the virulence gene profiles, the clinical outcome of the patients the resistance patterns might be predicted, and this information could be used in deciding appropriate antibiotic treatment.

A mutation at amino acid position 126 (changing valine to glutamic acid) in MexR was common in all exoU+ strains. Underexpression of mexR has been associated with antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa [46]. Mutations in mexR contribute to the over-expression of the MexAB-OprM efflux pump, [47, 48] which in turn is specific to increased resistance to beta-lactams [49]. The current study demonstrated that mutation in mexR was correlated with lower transcription of this gene in 75% of exoU+ strains. The higher expression of mexR in exoS+ strains observed here appears to support the hypothesis that possession of the exoU gene is associated with beta-lactam resistance.

Various different mutations in ampC and ampR between exoU and exoS subpopulations were revealed in the current study. Mutations in ampC and ampR were more common in exoU+ strains. Berrazeg et al [37] demonstrated that mutations in ampC at amino acid positions G27D, R79Q, T105A, Q156R, L176R, V205L, and G391A were not correlated with beta-lactam resistance and hence were excluded here from analysis in the current study. Mutations at amino acid positions Q155I and V356I in ampC were observed in exoU+ strains, and all these strains had increased gene expression of ampC, suggesting that these mutations may be responsible for this reduced expression. A few exoS+ strains and one exoU+ strain (PA34) did not have such mutations but were resistant to some beta-lactams. Point mutations in ampR (at 114, 182, 283, and 288) can also be responsible for beta-lactam resistance [38] and exoU+ strain PA34 carried mutations at E114A and G283E. Mutations at G283E and M288R in ampR were exclusive to exoU+ strains. These mutations were correlated with over-expression of ampC and ampR in exoU+ strains. The precise mechanism by which acquisition of the exoU associated genomic island results in these mutations is not known. For resistance of exoS+ strains, it is possible that beta-lactam resistance involves other resistance mechanisms, such as the upregulation of efflux systems MexCD-OprJ, MexEF-OprN, and MexXY-OprM, [50] and hence requires further study for elucidation.

Possession of exoU was also associated with higher MICs to fluoroquinolones compared to possession of exoS, and this has been shown in previous studies [5, 10, 45, 51–53]. Mutations in the QRDRs of target genes topoisomerase II (gryA and gyrB) and topoisomerase IV (parC and parE) have been previously shown to increase fluoroquinolone resistance in P. aeruginosa [54, 55]. Here, it was also observed that fluoroquinolone resistance in exoU strains was correlated with a combination of mutations in gyrA and parC. Sequence analysis indicated that six out of eight exoU strains had at least one mutation in either gyrA (T83I) or parC (S87L). Consistent with other studies, [54, 56] such mutations were responsible for very high MICs to fluoroquinolones. This suggests the possibility that more virulent strains of P. aeruginosa that have the exoU gene may evolve in the clinical environment where high concentrations of fluoroquinolones are used for treatment; for example, in eye infections [57, 58]. The conditions that favour selection of exoU+ strains might result in increased resistance to other antibiotics. In addition, this study also detected several mutations in QRDRs in the exoS+ population. Mutations at position E468D of gyrB and A473V of parE were associated with increase MICs to all tested fluoroquinolones. Such mutations have been previously associated with fluoroquinolone resistance P. aeruginosa [59, 60]. It appears that different types of mutations in QRDRs evolved in the exoU+ and exoS+ strains.

An exoS+ strain (PA55) was resistant to all beta lactams except aztreonam but no mutations were observed in the studied genes and expression of genes did not correlate with phenotypic resistance. Furthermore, an exoU+ strain (PA82) did not have any mutations in QRDRs but was resistant to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin. However, mutations in V126E the mexR of PA82 has been associated with resistance to fluoroquinolone [26, 61]. The evidence from the current study suggests that mutations A110T (PA34) and K76Q (PA175) in mexR may confer susceptibility to ceftazidime even in presence of the V126E mutation. This needs to be confirmed by further study.

In addition, we observed a link between the exoU and the origin of the strains in India because only one Australian strain (PA175) possessed the exoU gene and the resistance rate was higher in the cohort of Indian strains. However, it should be noted that the possession of exoU is highly correlated with antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa regardless of source and geographical site of isolation [5, 9, 10, 13, 45]. ExoU+ strains may have an evolutionary advantage by having the potential to be both more resistant and more virulent. This is supported by a study that showed higher prevalence of the exoU in isolates collected from the hospital environment [62]. A correlation between the geographic origin and the exoU carriage was observed in this study potentially due to the relatively unregulated use of antibiotics in India compared to Australia [63]. However, these observations require confirmation with a larger sample size that should include isolates from various sources and a study of associated epidemiological data.

In conclusion, exoU carrying strains, which are common in ocular isolates, showed different antibiotic resistance pattern from isolates with exoS genotype. The exoS+ strains may be protected from the action of antibiotics due to their ability to cause mammalian cells to ingest them (so-called invasive strains). Their residence inside mammalian cells may offer protection from antibiotics and so diminish selection pressure to convert to antibiotic resistance. The exoU+ strains had more mutations in drug resistance determining genes (gyrA, parC, mexR, ampC and ampR), which was likely to be the cause of higher antibiotic resistance in exoU+ strains. Differences in mutational rate in two different virulent genotypes indicate more virulent strains can favourably be evolved in the antibiotic rich environment. Therefore, understanding of both virulence traits and antibiotic resistance is essential for more effective prevention of antibiotic resistance.

Supporting information

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Singapore Centre for Environmental Life Sciences Engineering (SCELSE), whose research is supported by the National Research Foundation Singapore, Ministry of Education, Nanyang Technological University and National University of Singapore, under its Research Centre of Excellence Programme. Sequencing of DNA was carried out with the help of Daniela Moses and Stephan Schuster using the sequencing facilities at SCELSE. We are also thankful to UNSW high performance computing facility KATANA for providing us cluster for data analysis.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information file. All genomes are available from the NCBI database under bio-project accession number PRJNA431326.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Nosocomial infections in medical intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Critical care medicine. 1999;27(5):887–92. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yahr TL, Parsek MR. Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Prokaryotes: A Handbook on the Biology of Bacteria, Vol 6, Third Edition. 2006:704–13. 10.1007/0-387-30746-x_22 WOS:000268343700022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding C, Yang Z, Wang J, Liu X, Cao Y, Pan Y, et al. Prevalence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and antimicrobial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with pneumonia in mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;49:119–28. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heidary Z, Bandani E, Eftekhary M, Jafari AA. Virulence Genes Profile of Multidrug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Iranian Children with UTIs. Acta medica Iranica. 2016;54(3):201–10. Epub 2016/04/25. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho HH, Kwon KC, Kim S, Koo SH. Correlation between virulence genotype and fluoroquinolone resistance in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Annals of laboratory medicine. 2014;34(4):286–92. Epub 2014/07/02. 10.3343/alm.2014.34.4.286 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4071185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgescu M, Gheorghe I, Curutiu C, Lazar V, Bleotu C, Chifiriuc MC. Virulence and resistance features of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from chronic leg ulcers. BMC infectious diseases. 2016;16 Suppl 1:92 Epub 2016/05/14. 10.1186/s12879-016-1396-3 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4890939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawa T, Shimizu M, Moriyama K, Wiener-Kronish JP. Association between Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretion, antibiotic resistance, and clinical outcome: a review. Critical care (London, England). 2014;18(6):668 Epub 2015/02/13. 10.1186/s13054-014-0668-9 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4331484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran QT, Nawaz MS, Deck J, Foley S, Nguyen K, Cerniglia CE. Detection of type III secretion system virulence and mutations in gyrA and parC genes among quinolone-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from imported shrimp. Foodborne pathogens and disease. 2011;8(3):451–3. Epub 2010/12/02. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0687 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agnello M, Finkel SE, Wong-Beringer A. Fitness Cost of Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Differs by Type III Secretion Genotype. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:1591 Epub 2016/10/21. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01591 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5047889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garey KW, Vo QP, Larocco MT, Gentry LO, Tam VH. Prevalence of type III secretion protein exoenzymes and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from bloodstream isolates of patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Journal of chemotherapy. 2008;20(6):714–20. 10.1179/joc.2008.20.6.714 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choy MH, Stapleton F, Willcox MD, Zhu H. Comparison of virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from contact lens- and non-contact lens-related keratitis. Journal of medical microbiology. 2008;57(Pt 12):1539–46. 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/003723-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finck-Barbancon V, Goranson J, Zhu L, Sawa T, Wiener-Kronish JP, Fleiszig SM, et al. ExoU expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa correlates with acute cytotoxicity and epithelial injury. Molecular microbiology. 1997;25(3):547–57. Epub 1997/08/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agnello M, Wong-Beringer A. Differentiation in Quinolone Resistance by Virulence Genotype in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PloS one. 2012;7(8). 10.1371/journal.pone.0042973 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3414457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato H, Frank DW, Hillard CJ, Feix JB, Pankhaniya RR, Moriyama K, et al. The mechanism of action of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-encoded type III cytotoxin, ExoU. The EMBO journal. 2003;22(12):2959–69. 10.1093/emboj/cdg290 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC162142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser AR. The type III secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: infection by injection. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2009;7(9):654–65. 10.1038/nrmicro2199 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2766515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berthelot P, Attree I, Plesiat P, Chabert J, de Bentzmann S, Pozzetto B, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of type III secretion system in a cohort of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia isolates: evidence for a possible association between O serotypes and exo genes. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2003;188(4):512–8. Epub 2003/08/05. 10.1086/377000 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleiszig SM, Wiener-Kronish JP, Miyazaki H, Vallas V, Mostov KE, Kanada D, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-mediated cytotoxicity and invasion correlate with distinct genotypes at the loci encoding exoenzyme S. Infection and immunity. 1997;65(2):579–86. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC176099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulasekara BR, Kulasekara HD, Wolfgang MC, Stevens L, Frank DW, Lory S. Acquisition and evolution of the exoU locus in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of bacteriology. 2006;188(11):4037–50. 10.1128/JB.02000-05 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1482899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfgang MC, Kulasekara BR, Liang X, Boyd D, Wu K, Yang Q, et al. Conservation of genome content and virulence determinants among clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(14):8484–9. 10.1073/pnas.0832438100 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC166255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauser AR, Cobb E, Bodi M, Mariscal D, Valles J, Engel JN, et al. Type III protein secretion is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Critical care medicine. 2002;30(3):521–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart RM, Wiehlmann L, Ashelford KE, Preston SJ, Frimmersdorf E, Campbell BJ, et al. Genetic characterization indicates that a specific subpopulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is associated with keratitis infections. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2011;49(3):993–1003. 10.1128/JCM.02036-10 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3067716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi S, Suzuki T, Kobayashi T, Oka N, Ishikawa E, Shinomiya H, et al. Genotypic analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from ocular infection. Journal of infection and chemotherapy : official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2014;20(7):407–11. Epub 2014/04/22. 10.1016/j.jiac.2014.02.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tingpej P, Smith L, Rose B, Zhu H, Conibear T, Al Nassafi K, et al. Phenotypic characterization of clonal and nonclonal Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from lungs of adults with cystic fibrosis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2007;45(6):1697–704. 10.1128/JCM.02364-06 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1933084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Almeida Silva KCF, Calomino MA, Deutsch G, de Castilho SR, de Paula GR, Esper LMR, et al. Molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in a burn center. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2017;43(1):137–43. Epub 2016/09/07. 10.1016/j.burns.2016.07.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacoby GA. AmpC beta-lactamases. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2009;22(1):161–82, Table of Contents. 10.1128/CMR.00036-08 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2620637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poole K. Multidrug efflux pumps and antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related organisms. Journal of molecular microbiology and biotechnology. 2001;3(2):255–64. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute(CLSI). Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard—Ninth Edition CLSI; 2012;32(M07-A9). Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nature protocols. 2008;3(2):163–75. 10.1038/nprot.2007.521 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute(CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-second information supplement. CLSI document M100-S22. 2012;32(3). Wayne, PA.

- 30.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 6.0: The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 2016. Available from: http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/.

- 31.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–77. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3342519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2014;30(14):2068–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–9. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3322381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2009;25(16):2078–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2723002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. 2012;6(2):80–92. Epub 2012/06/26. 10.4161/fly.19695 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3679285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruchmann S, Dotsch A, Nouri B, Chaberny IF, Haussler S. Quantitative contributions of target alteration and decreased drug accumulation to Pseudomonas aeruginosa fluoroquinolone resistance. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013;57(3):1361–8. 10.1128/AAC.01581-12 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3591863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berrazeg M, Jeannot K, Ntsogo Enguéné VY, Broutin I, Loeffert S, Fournier D, et al. Mutations in β-Lactamase AmpC Increase Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates to Antipseudomonal Cephalosporins. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2015;59(10):6248–55. 10.1128/AAC.00825-15 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4576058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tam VH, Schilling AN, LaRocco MT, Gentry LO, Lolans K, Quinn JP, et al. Prevalence of AmpC over-expression in bloodstream isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(4):413–8. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01674.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaez H, Faghri J, Isfahani BN, Moghim S, Yadegari S, Fazeli H, et al. Efflux pump regulatory genes mutations in multidrug resistance Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from wound infections in Isfahan hospitals. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:117 10.4103/2277-9175.133183 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4063115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hocquet D, Bertrand X, Kohler T, Talon D, Plesiat P. Genetic and phenotypic variations of a resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa epidemic clone. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2003;47(6):1887–94. 10.1128/AAC.47.6.1887-1894.2003 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC155826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker SE, Lorsch J. Chapter Nineteen—RNA Purification–Precipitation Methods In: Lorsch J, editor. Methods in enzymology. 530: Academic Press; 2013. p. 337–43. 10.1016/B978-0-12-420037-1.00019-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nature protocols. 2008;3(6):1101–8. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu DI, Okamoto MP, Murthy R, Wong-Beringer A. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: risk factors for acquisition and impact on outcomes. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2005;55(4):535–41. 10.1093/jac/dki026 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleiszig SM, Lee EJ, Wu C, Andika RC, Vallas V, Portoles M, et al. Cytotoxic strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa can damage the intact corneal surface in vitro. The CLAO journal : official publication of the Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmologists, Inc. 1998;24(1):41–7. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong-Beringer A, Wiener-Kronish J, Lynch S, Flanagan J. Comparison of type III secretion system virulence among fluoroquinolone-susceptible and -resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2008;14(4):330–6. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01939.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dumas JL, van Delden C, Perron K, Kohler T. Analysis of antibiotic resistance gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by quantitative real-time-PCR. FEMS microbiology letters. 2006;254(2):217–25. Epub 2006/02/01. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00008.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saito K, Yoneyama H, Nakae T. nalB-type mutations causing the overexpression of the MexAB-OprM efflux pump are located in the mexR gene of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosome. FEMS microbiology letters. 1999;179(1):67–72. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adewoye L, Sutherland A, Srikumar R, Poole K. The mexR repressor of the mexAB-oprM multidrug efflux operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: characterization of mutations compromising activity. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184(15):4308–12. 10.1128/JB.184.15.4308-4312.2002 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC135222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Masuda N, Sakagawa E, Ohya S, Gotoh N, Tsujimoto H, Nishino T. Substrate specificities of MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexXY-oprM efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2000;44(12):3322–7. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC90200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poole K. Efflux-mediated antimicrobial resistance. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2005;56(1):20–51. 10.1093/jac/dki171 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park MH, Kim SY, Roh EY, Lee HS. Difference of Type 3 secretion system (T3SS) effector gene genotypes (exoU and exoS) and its implication to antibiotics resistances in isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from chronic otitis media. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2017;44(3):258–65. Epub 2016/07/28. 10.1016/j.anl.2016.07.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borkar DS, Acharya NR, Leong C, Lalitha P, Srinivasan M, Oldenburg CE, et al. Cytotoxic clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified during the Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial show elevated resistance to fluoroquinolones. BMC ophthalmology. 2014;14:54 Epub 2014/04/26. 10.1186/1471-2415-14-54 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4008435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitov I, Strateva T, Markova B. Prevalence of Virulence Genes Among Bulgarian Nosocomial and Cystic Fibrosis Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2010;41(3):588–95. 10.1590/S1517-83822010000300008 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3768660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ling JM, Chan EW, Lam AW, Cheng AF. Mutations in Topoisomerase Genes of Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Salmonellae in Hong Kong. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2003;47(11):3567–73. 10.1128/AAC.47.11.3567-3573.2003 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC253778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee JK, Lee YS, Park YK, Kim BS. Alterations in the GyrA and GyrB subunits of topoisomerase II and the ParC and ParE subunits of topoisomerase IV in ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2005;25(4):290–5. Epub 2005/03/24. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.11.012 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hirose K, Hashimoto A, Tamura K, Kawamura Y, Ezaki T, Sagara H, et al. DNA sequence analysis of DNA gyrase and DNA topoisomerase IV quinolone resistance-determining regions of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and serovar Paratyphi A. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2002;46(10):3249–52. 10.1128/AAC.46.10.3249-3252.2002 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC128770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green M, Apel A, Stapleton F. Risk factors and causative organisms in microbial keratitis. Cornea. 2008;27(1):22–7. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318156caf2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keay L, Edwards K, Stapleton F. Referral pathways and management of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Australia and New Zealand. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2008;36(3):209–16. 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01722.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee JK, Lee YS, Park YK, Kim BS. Alterations in the GyrA and GyrB subunits of topoisomerase II and the ParC and ParE subunits of topoisomerase IV in ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2005;25(4):290–5. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akasaka T, Tanaka M, Yamaguchi A, Sato K. Type II topoisomerase mutations in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in 1998 and 1999: role of target enzyme in mechanism of fluoroquinolone resistance. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2001;45(8):2263–8. 10.1128/AAC.45.8.2263-2268.2001 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC90640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choudhury D, Ghosh A, Dhar Chanda D, Das Talukdar A, Dutta Choudhury M, Paul D, et al. Premature Termination of MexR Leads to Overexpression of MexAB-OprM Efflux Pump in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Tertiary Referral Hospital in India. PloS one. 2016;11(2):e0149156 10.1371/journal.pone.0149156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bradbury RS, Roddam LF, Merritt A, Reid DW, Champion AC. Virulence gene distribution in clinical, nosocomial and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of medical microbiology. 2010;59(Pt 8):881–90. Epub 2010/05/01. 10.1099/jmm.0.018283-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Laxminarayan R, Matsoso P, Pant S, Brower C, Røttingen J-A, Klugman K, et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. The Lancet. 2016;387(10014):168–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, et al. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000;406(6799):959–64. 10.1038/35023079 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information file. All genomes are available from the NCBI database under bio-project accession number PRJNA431326.