Abstract

Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) is used as malaria chemoprophylaxis for pregnant women and children in Ghana. Plasmodium falciparum resistance to SP is linked to mutations in the dihydropteroate synthase gene (pfdhps), dihydrofolate reductase gene (pfdhfr) and amplification of GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (pfgch1) gene. The pfgch1 duplication is associated with pfdhfr L164, a crucial mutant for high level pyrimethamine resistance which is rare in Ghana. The presence of amplified pfgch1 in Ghanaian isolates could be an indicator of the evolution of the L164 mutant. This study therefore determined the pfgch1 copy number variations and SP resistance mutations in clinical isolates from Ghana. One hundred and ninety-two (192) blood samples collected from children aged ≤14 years with uncomplicated malaria in 2013–14 and 2015–16 were used. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was used to detect the pfgch1 copy number and nested PCR-Sanger sequencing used to detect mutations in pfdhps and pfdhfr genes. Twelve parasites (6.3%) harbored double copies of the pfgch1 gene out of the 192 samples. Of the 12, 75% had the pfdhfr I51-R59-N108, 92% had the pfdhps G437 mutant, 8% had the pfdhps E540 and 67% had the SP resistance haplotype IRNG. No L164 was detected in samples with amplified pfgch1. The rare T108 mutant associated with cycloguanil resistance showed predominance (60%) over N108 in the 2015–16 isolates. The observation of parasites with increased copy number of pfgch1 gene is indicative of the future evolution of the rare quadruple pfdhfr mutant, I51-R59-N108-L164, in Ghanaian parasites. Mutant pfdhps isolates also had increased gch1 copy number suggestive that it may also facilitate sulphadoxine resistance. The selection of parasites with pfgch1 gene amplification will enhance the sustenance and persistence of parasites with SP resistance in the country. Policy makers need to begin the search for a replacement chemoprophylaxis drug for malaria vulnerable groups in Ghana.

Introduction

Malaria is still a devastating disease in sub-Saharan Africa especially in children under the age of 5 years, pregnant women and non-immune travelers to the region. Chemoprophylaxis against the disease in these vulnerable groups involve the use of antifolate drugs, i) sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) is used for intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women (IPTp) and seasonal malaria chemoprophylaxis (SMC) for children under 5 in seasonal malaria transmission areas; ii) atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone) is used by non-immune travelers to the malarious areas [1]. These antimalarials kill parasites by targeting enzymes in its de novo folate pathway such as the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS). The inhibition of these enzymes in the pathway, limits the availability of folate derivatives that serve as one-carbon carriers during nucleotide biosynthesis and amino acid metabolism in the parasite. Mutations in these genes therefore decrease the binding affinity of the drugs to the targeted enzymes because of the changes in the conformity of the protein [2].

P. falciparum resistance to SP has been linked to single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the pfdhfr (pyrimethamine resistance) and pfdhps (sulphadoxine resistance) genes. The SNPs in the pfdhfr gene are Asn51Ile (N51I), Cys59Arg (C59R), Ser108Asn (S108N), and Ile164Leu (I164L) whilst those of the pfdhps gene are Ser436Ala/Phe (S436A/F), Ala437Gly (A437G), Lys540Glu (K540E), Ala581Gly (A581G), and Ala613Tyr (A613S/T) [3–7]. The S108N mutation is the pfdhfr core mutation which predicts a 10 fold increase in parasite resistance to pryrimethamine whilst the core mutations for sulphadoxine resistance are pfdhps mutationsA437G and G540E [8]. The resistance level of parasitesis linked to the number of point mutations or haplotypes of the 2 genes and therefore, multiple mutations are responsible for high levels of SP resistance [9]. There is a synergistic effect in conferring resistance for SP with the quintuple mutant of pfdhfr and pfdhps, haplotype I51-R59-N108-G437-E540 [10]. Reports of increasing prevalence of these mutations have been reported in African malaria endemic areas including Ghana [8,11–13].

The efficacy of SP for malaria prevention might have reduced drastically because of reports from surveillance studies of circulating parasites with resistance haplotypes [14]. This observed increase in parasites with resistance haplotypes is due to selection by drug pressure from the use of SP for IPTp and SMC as well as the use of antifolate containing antibiotics in the country. Genomic analyses of the malaria parasites showed copy number variations (CNV) of GTP cyclohydrolase I gene (pfgch1) which encodes the first and the rate-limiting enzyme of the de novo folate biosynthesis. Increased copy number of gch1 has been linked to SP resistance in Southeast Asia (SEA) [15,16]. Multiple copies of pfgch1 have been shown to have a direct association with point mutations in pfdhfr but not pfdhps in SEA, which was confirmed in a separate study using genetic manipulations of parasite lines[17,18]. The increased copy number of pfgch1 were detected in a study looking at geographically distinct parasites with known drug resistance profiles [18]. In Africa, a recent study using Malawian parasites reported a novel pfgch1 promoter duplication in parasites with quintuple mutations (I51-R59-N108-G437-E540) which differs from the whole gene duplication found in Southeast Asia [19].

The drug-resistant mutations in the two genes, though advantageous under SP pressure, they render the parasite less fit due to the changes at the enzymes active sites [20–22]. It was therefore suspected that multiple copies of gch1 could compensate for the putatively fitness-reducing mutations in pfdhfr and pfdhps by providing higher concentrations of downstream substrates in its folate-biosynthetic pathway [23]. This phenomenon may also directly increase the level of SP resistance in the parasite[17]. A joint analysis of gch1 CNVs, pfdhfr and pfdhps SNPs may therefore shed more light on the molecular mechanisms of SP resistance and how these resistant isolates are maintained in circulation in malaria endemic areas like Ghana.

Materials and methods

Study design and sites

Filter paper blood blots were prepared from whole blood samples collected from children aged 6 months to 14 years with uncomplicated malaria in 2013–2016 from four sentinel sites for monitoring antimalarial drug efficacy, Accra, Cape Coast, Kintampo and Navrongo (Fig 1). These sites are located in the three different ecological zones in Ghana with different malaria transmission intensities. These children were enrolled after obtaining informed consent from their parents or guardians to participate in the studies.

Fig 1. Map of Ghana showing the four study sites.

Sites shown by black arrows.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committees and Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of the Ghana health service, the Noguchi Memorial Institute of Medical Research, the Kintampo Health Research Centre and the Navrongo Health Research Centre prior to the conduct of these studies. The proposals for ethical clearance stated the categorical use of the samples for future molecular analysis. A written informed consent was used and the IRB approved the consent procedure.

Molecular analysis

DNA extraction and nPCR amplification of genes

Genomic DNA was extracted from 202 dried blood blot filter paper samples using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. The nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR) was used to amplify the target region within the pfdhfr and pfdhps genes with fragment sizes of 616bp and 647bp, respectively following protocol [24,25] with minor modifications. A 25μl reaction mix contained 1U High Fidelity Taq polymerase (Roche, UK), 0.2mM dNTP mix, 1.5mM MgCl2 and 0.25μM of each primer and 2μl DNA template for the primary PCR. For the secondary PCR, the same reaction concentrations were used as in the outer PCR but in a final volume of 50 μl. The pfdhfr primers were F1: 5’-TCC TTT TTA TGA TGG AAC AAG-3' and R1: 5’-AGT ATA TAC ATC GCT AAC AGA-3'; F2: 5’- TTT ATG ATG GAA CAA GTC TGC -3' and R2: 5’-ACT CAT TTT CAT TTA TTT CTG G-3' and those for pfdhps were F1: 5’-AAC CTA AAC GTG CTG TTC AA-3' and R1: 5’-AAT TGT GTG ATT TGT CCA CAA-3'; F2: 5’-ATG ATA AAT GAA GGT GCT AG-3' and R2: 5’-TCA TTT TGT TGT TCA TCA TGT-3'. The cycling conditions for both genes were for the primary reaction, an initial denaturation of 94°C for 5 mins followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30secs, 50°C for 30secs and 68°C for 1min and final extension of 68°C for 5 mins and the secondary reactions had an annealing temperature of 52°C and 30 cycles. PCR products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel with ethidium bromide to determine the specificity and success of the PCR for sequencing.

Sequencing of pfdhfr and pfdhps genes

Sanger sequencing of both dhfr and dhps fragments were performed at Macrogen (Denmark). One hundred and ninety two of the 202 samples were successfully sequenced. Samples with multiple peaks at any of the codons genotyped were trimmed and only high-quality peaks were called and included in the analysis. The sequenced results in the ABI file format were analysed using Qiagen CLC Main Workbench analysis software (version 7.8.1) and the Codon Code Aligner software (version 7.0.1). Detection of SNPs and haplotypes were done by aligning the sample sequences with the reference 3D7 (Wild-type) sequences retrieved from www.Plasmodb.org.

Quantitative real-time PCR to determine copy number variation of pfgch1

QRT-PCR was carried out on all the 202 DNA samples to determine copy numbers using the SYBR-Green method by Heinberg et al [17] with minor modifications. All reactions were performed at primer concentrations of 0.5 μM, 1X PerfeCTa SYBR Green Supermix (Quantabio) and 2μl of DNA template. Each sample was run in triplicate using the QuantStudio5 (Applied Biosystems) real-time PCR machine. The gch1 primers were F: 5'-ATG AAA CAC ATA ATA TGG AAG AAA AA-3 and R: 5'-TCC TTT TCA TCT ATC ACA ACA AGG-3'; seryl-tRNA synthetase primers were F: 5'-AAG TAG CAG GTC ATC GTG GTT-3' and R: 5'-TTC GGC ACA TTC TTC CAT AA-3'). The cycling conditions were an initial 50°C for 2 mins and 95°C for 1 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 secs, 54°C for 40 secs and 60°C for 1 min and a melt curve stage of 95°C for 15 secs, 60°C for 1 min and 95°C for 1 sec. The seryl-tRNA synthetase was used as the endogenous control. Reference samples (Dd2 and 3D7) with known gch1 copy numbers and a non-template negative controls were included in each run. Samples with amplified gch1 copy number were repeated for certainty. The melting curve analysis was performed for each run and experiments with non-specific products, Ct > 32 or standard deviation (SD) ≥ 0.5 were repeated. The delta delta Ct formula (2-ΔΔCt) was used to estimate the relative copy numbers.

Determination of pfgch1 gene expression levels

Clinical isolates harboring different copies of the pfgch1 gene and laboratory strain Dd2 (control) were thawed and put into continuous culture following the protocol by Trager and Jensen [26]. Briefly, the thawed parasites were suspended in a complete parasite medium (CPM) at 5% hematocrit using un-infected human group O+ erythrocytes. At a parasitaemia of 2 to 5%, the parasites were synchronized using sorbitol and put back into culture until they developed into late trophozoites, a stage where the pfgch1 has been shown to be highly expressed [27]. The RNA was isolated using AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini kit protocol by Qiagen (Qiagen, Germany) and the RNA samples treated with DNase to remove all residue DNA. The cDNA synthesis was then carried out with a control reaction (without a reverse transcriptase) using the Superscript III first-strand protocol following manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The cDNA synthesis reaction condition includes 25°C for 10 min, 50°C for 50 min and 85°C for 5 min. Following the cDNA synthesis, 1 μl of RNase H was added to each reaction, mixed and incubated at 37°C for 20 min and 95°C for 10 min to remove RNA residues. QRT-PCR was then carried out on the cDNA with the same reaction conditions as described for the copy number determination and the Ct values converted to expression levels using the 2-ΔΔCt formula [28].

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS software (version 20) and GraphPad Prism version 6. Descriptive analyses for mutations were performed. Chi-square and multiple comparison tests were used to compare the difference between groups. All tests were considered statistically significant with P<0.005.

Results

Conventional nested PCR (nPCR) and Sanger sequencing were successfully performed on 192 samples for the detection of SNPs in the pfdhfr and pfdhps genes. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on the same number of samples for the copy number variation in gch1 gene. Of the 192 samples, 100 were collected in 2013–14 and 92 in 2015–16. The sites for the 2013–14 samples were Accra (37), Kintampo (39) and Navrongo (24) and those of 2015–16 were Cape-Coast (47) and Navrongo (45).

Prevalence of mutations in pfdhfr and pfdhps

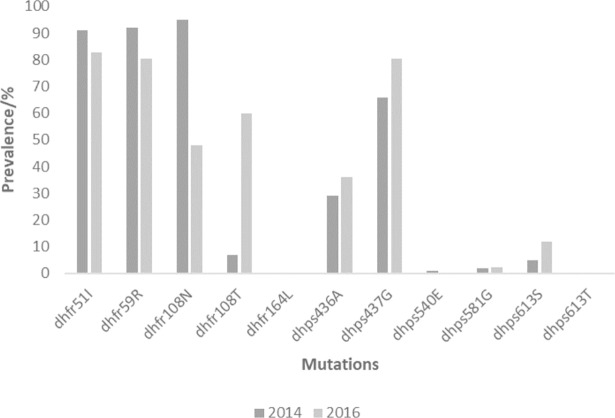

The sequence analysis of the SNPs in the pfdhfr gene revealed that the prevalence of I51, R59, N108 and T108 in 2013–14 to be 91%, 92%, 95% and 7% respectively. The prevalence of these mutation in 2015–16 was 82.65, 80.6%, 47.8% and 59.9% respectively for I51, R59, N108 and T108. Only one sample had the wildtype S108 in the 2013–14 samples but none had the wildtype in the 2015–16 samples. Three samples had both N108 and T108 in the 2013–2014 and 7 had both mutations in the 2015–16 samples. An increasing trend for T108 was observed which seems to be taking over N108 prevalence especially in Navrongo. No mutations were detected at codons 50 and 164 of the pfdhfr gene. The distribution of the mutations per site is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Proportions of samples per site with pfdhfr and pfdhps mutations.

| Sites | pfdhfr mutations | pfdhps mutations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | I51 | R59 | N108 | T108 | A436 | G437 | E540 | G581 | S613 | |

| 2013–14 | ||||||||||

| Accra | 37 | 86.5 | 86.5 | 97.3 | 0 | 24.3 | 59.5 | 0 | 5.4 | 8.1 |

| Kintampo | 39 | 94.9 | 92.39 | 92.3 | 7.7 | 28.2 | 66.7 | 2.6 | 0 | 5.1 |

| Navrongo | 24 | 91.7 | 100 | 95.8 | 16.7 | 37.5 | 75.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2015–16 | ||||||||||

| Cape-Coast | 47 | 80.9 | 76.6 | 42.6 | 57.5 | 27.7 | 78.7 | 0 | 2.1 | 10.6 |

| Navrongo | 45 | 84.4 | 84.4 | 53.3 | 62.2 | 44.4 | 82.2 | 0 | 2.2 | 13.3 |

For the pfdhps mutations the prevalence for 2013–14 were, 29.0%, 66.0%, 1.0%, 2.0% and 5.0% for A436, G437, E540, G581, S613 respectively. The prevalence for 2015–16 for A436, G437, E540, G581, S613 were 35.9%, 80.4%, 0%. 2.2% and 11.9% respectively. No T613 mutation was observed in all samples. The distribution of the pfdhps mutations is per site is also shown in Table 1. The overall prevalence of the pfdhfr and pfdhps mutations in the country for the two time points are shown in Fig 2.

Fig 2. The prevalence of the pfdhfr and pfdhps mutations for the two time points in Ghana.

Prevalence of haplotypes of pfdhfr and pfdhps

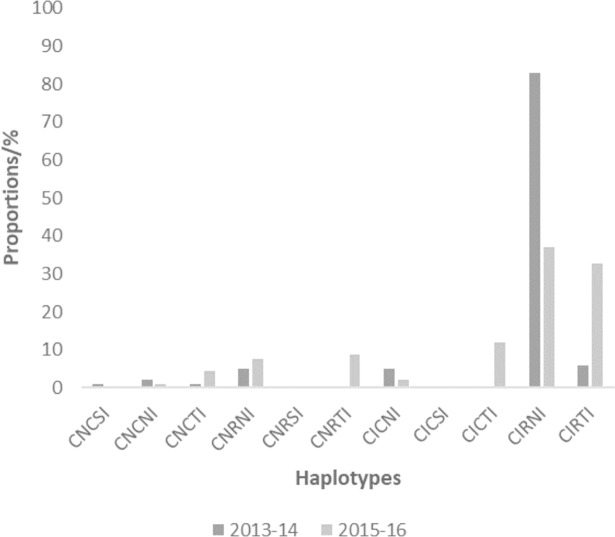

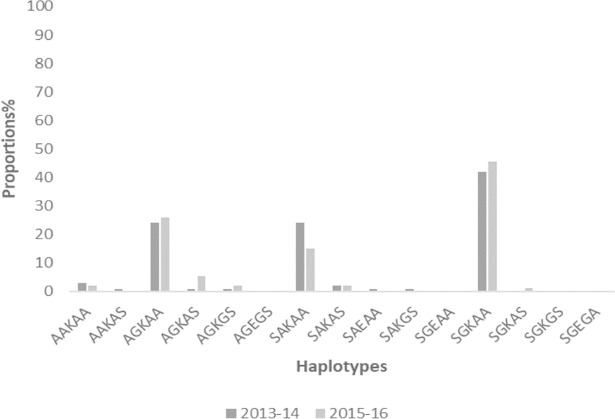

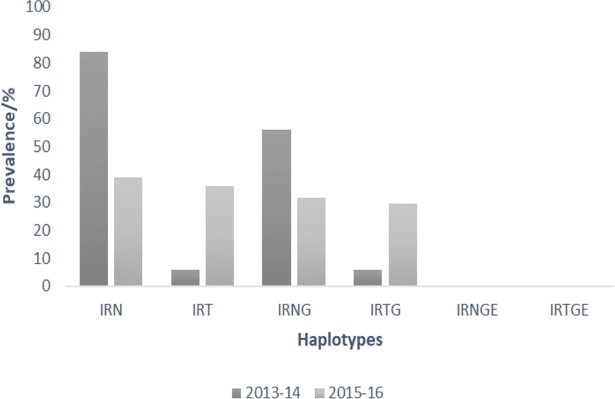

Proportions of samples from the two time points with haplotypes from pfdhfr codons 50-51-59-108-164 and pfdhps codons 436-437-540-581-613 are shown in Figs 3 and 4. The prevalence of mutant haplotypes associated with pyrimethamine resistance, pfdhfr triple mutants I51-R59-N108 (IRN) and I51-R59-T108 (IRT), as well as those for sulphadoxine resistance, pfdhps double mutant G437-E540 (GE), quadruple mutant IRNG and quintuple mutant IRNGE are shown in Fig 5. No quintuple mutant was observed in the samples for both 2013–14 and 2015–16 timepoints.

Fig 3. The proportion of isolates with pfdhfr haplotypes for the two time points in Ghana.

Fig 4. The proportion of isolates with pfdhps haplotypes for the two time points in Ghana.

Fig 5. The prevalence of the SP and cycloguanil resistance haplotypes for the two time points in Ghana.

Copy number variations of the pfgch1 gene in P. falciparum isolates

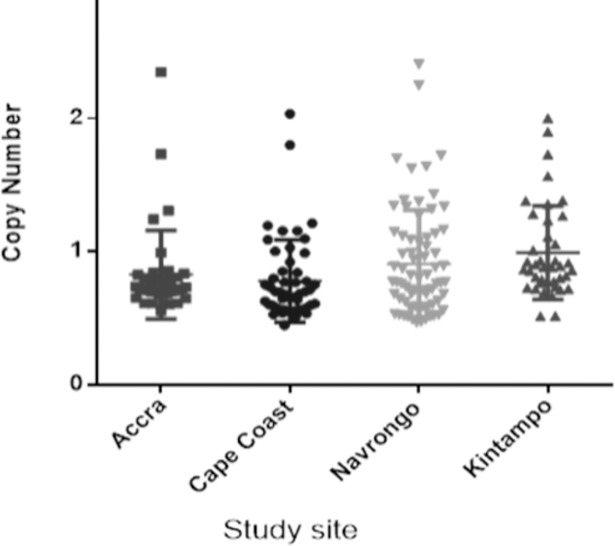

Gch1 copy number (CN) was determined in 192 samples, of which 6.3% (12/192) had an estimated copy number of 2. The distribution of the estimated CN from the isolates is shown in Fig 6. The highest proportion with a CN of 2 was seen in the 75%, (9/12) of samples from 2013–14 of which Accra had 2, Kintampo had 4 and Navrongo had 3. Only 3 samples from 2015–16 had a CN of 2, 2 from Navrongo and 1 from Cape-Coast.

Fig 6. The scatter plot of estimated pfgch1 copy number per site.

Each dot represents the estimated copy number.

Expression levels of pfgch1 in field isolates

To ascertain the transcriptional importance of gch1 gene dosage, the expression levels of DD2 strain and field isolates with differing gch1 gene copies were determined. Isolates with a single copy had a mean relative expression of 0.44 as compared to 1.55 expression level amongst parasites with double gch1 gene as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The gch1 expression levels in field isolates with varying gene copy number.

| Sample ID | pfgch1 CN | pfgch1 expression level |

|---|---|---|

| Dd2 | 2 | 1.454 |

| EIMK526 | 2 | 1.589 |

| EIMK481 | 2 | 1.602 |

| EIMA226 | 1 | 0.582 |

| EIMA237 | 1 | 0.30 |

pfdhfr and pfdhps SNPs and haplotypes with increased pfgch1 CN

The pfdhfr and pfdhps mutations and increased gch1 copy number were analysed to assess their dependence. The SNPs with the increased gch1 gene included the triple mutant IRN of the pfdhfr gene and the G437 the pfdhps gene. Of the 12 samples with increased copy number, 75% (9/12) had the triple mutant IRN, 92% (11/12) had G437 mutation and 67% (8/12) had both IRN and G437 and 8% (1/12) had the E540. Of the 111 samples with the quadruple mutant, 8% (9/111) had the increased copy number of pfgch1 whilst the majority had single copy of the gene. No significant difference was observed between those with increased copy number and single copy for the quadruple mutants (p = 0.236).

Discussion

In this study, we determined the presence of amplified pfgch1 gene and the pfdhfr and pfdhps SNPs in P. falciparum clinical isolates from Ghana. This is important to clarify the underlying factors for the sustenance and persistence of the less fit SP resistant parasites in the population. Trajectory analysis of the pfgch1 amplification has revealed its role in the fixation of pfdhfr mutants in the parasite population but with a minor influence in directing drug resistance [17,28] Indeed, for parasites with multiple pfdhfr mutations, duplication of the pfgch1 gene provided fitness advantage rather than directly reducing pyrimethamine susceptibility. This study detected increased copy number of pfgch1 gene in Ghanaian clinical isolates and observed that the copy number corresponds to the gene expression levels. The presence of the amplified gene did correlate not only with pfdhfr mutations as reported from other studies but also with pfdhps mutations in Ghanaian isolates. Since the quadruple mutant of pfdhfr with L164 which confers high level pyrimethamine resistance has been linked to the presence of increased pfgch1 copy number [18,19], it could be indicative of a near future evolution of this rare mutation in the parasite population of Ghana. The consequence of this may render the prophylactic drug for the vulnerable groups ineffective.

Until recently, increased pfgch1 copy number was seen only in isolates from the SEA region specifically Thailand [29]. CNV of this gene has been associated with pyrimethamine resistance in SEA and South Asia [16,18,19]. For the first time, a report from Ravenhall and others showed increased pfgch1 promoter gene in African isolates from Malawi, Ghana, Guinea, Gambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo [19]. However, they observed a whole duplication of the gene in isolates from Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Myanmar and the only African country was Ghana (5%) [19]. This current study observed the amplification of the whole gene in about 7% of the clinical isolates and was linked predominantly with the triple mutant IRN as observed in other studies [19,28]. Interestingly, the whole gene amplification also correlated with the presence of pfdhps G437 in this study just as the promoter amplification seen in the Ghanaian isolates from the other study. The IRNG which is the haplotype for SP resistance also seen in about 70% of the samples with amplified pfgch1. The role of pfgch1 in compensating for the fitness cost may be a result of increased copies of the gene which could lead to high transcriptional and enzyme levels by many folds [18,30]. The copy number observed in this study was directly proportional to the transcriptional levels and as enzyme levels increase, consequently there will be an increase the downstream metabolites which will affect activities of the DHFR and DHPS enzymes. Thus, in the less fit parasites with SP-resistant pfdhfr and pfdhps haplotypes such an adaptation compensates for their fitness cost [28].

The pfdhfr mutation at codon 108 is from serine to asparagine or threonine (S108N/T). It is worth mentioning that from studies conducted in the past on SP resistance markers in Ghana, the T108 has not been reported in Ghanaian isolates. This mutant associated with cycloguanil resistance [10,31,32] was prevalent in 7% of the isolates from 2013–14 and 60% of those collected in 2015–16. In all, 7 samples had both N108 and T108. It was observed that either the sample may have one or the other, however majority of the samples in the 2015–16 group had the T108. In addition, 2 samples with IRT had an increased pfgch1 gene. Cycloguanil is a metabolite of proguanil which is in combination with atovaquone as malarone. Malarone is used by non-immune travelers to malaria endemic areas for prophylaxis, as such with this observation, amendment in treatment policies is recommended.

The high transmission areas of Navrongo and Kintampo seemed to have higher proportions of parasites with double pfgch1 50% and 33% respectively compared to the lower transmission sites, Accra and Cape-Coast with one sample each. The role of transmission and the evolution of mutations in parasites is quite clear especially for the pfcrt, pfmdr1,pfdhfr and pfdhps genes. The pfgch1 copy number evolution is as a result of an adaptation to drug pressure [18,23], therefore the percentage prevalence observed in this study indicate a high use of antifolate drug in the country. It must be emphasized that although the use of SP in Ghana is restricted to pregnant women and children as prophylaxis, most chemical and pharmacy shops still stock and sell the drug to individuals outside these groups [33]. Another reason for the relatively high drug pressure may be the use of antifolate-containing antibiotics prescribed in the country.

After the change of antimalarial drug treatment policy in Ghana in 2005, SP had been used as an IPTp and there have been reports of increased SP resistance markers over the years[8,24]. Studies by Mockenhaupt et al. in 2005 reported the presence of 47% of dhfr triple and 0.8% of quintuple mutants [34]. The above frequencies are higher amongst parasites collected in 2007/2008 by Alam et al, where the triple dhfr and quintuple mutants were reported as 58.7% and 1.8% respectively [24]. Duah and colleagues also reported the prevalence of the triple dhfr and quintuple mutants in parasites collected in 2010 as 55% and 1.12% respectively[8]. A recent report by Abugri and colleagues have also affirmed an increasing trend in the triple and quadruple mutants for SP resistance [13]. The relatively high prevalence of the triple mutant IRN, 84% for 2013–14, declined to 39% due to the upsurge of the T108, such that IRT was 36%. This also affected the prevalence of the quadruple mutant IRNG which was 56% for 2013–14 but was 32% in 2015–16 and therefore the IRNTG was 29%. As such no quintuple mutants for SP resistance were observed in the current study although one sample from the 2013–14 group had the pfdhps E540 mutant but with a A437.

The increased prevalence of the known resistant markers in our study may be attributed to drug pressures, however the presence of the amplified pfgch1 will exacerbate the existing problem and may help to maintain these resistant parasites and the evolution of new mutants. Drug pressure selecting these mutations is not only for SP use but also for other antifolates. A sulfonamide antifolate-containing antibiotic known as cotrimoxazole which is a combination of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole is often prescribed to treat pneumonia, bronchitis, infections of the urinary tract, ears and intestines, and as prophylaxis in HIV infected individuals. The administration of this drug in patients with bacterial and malaria co-infection may, therefore, lead to high drug pressure with a consequent selection for drug resistant parasites. The most critical scenario with this new parasite adaption is the ability of mutants to equally or favorably compete with the wild type in the absence or reduced SP drug pressure and thus cause the expansion and persistence of the resistant type. If this speculated mechanism holds, then it may jeopardize the use of SP drug and other antifolate-containing antibiotics in Ghana in the near future. It is interesting to note that there are still several reports of high cases of SP resistant parasites in areas with no or restricted use of the SP drug [35–37].

Conclusion

The observation of that rare mutation (amplified pfgch1) in Ghanaian isolates indicates that there is an upcoming force to aid in the sustenance and persistence of parasites with SP resistance mutations. In addition, it may influence the evolution of new mutations to invoke a relatively higher level of resistance of SP in the Ghanaian parasite population. Therefore with the emergence of such a rare mutation in this geographical region, it is important that policy makers begin the search for a new chemoprophylactic drug to replace SP for the two most vulnerable groups, pregnant women and children in Ghana.

Supporting information

This excel sheet contains data supporting the findings in this study. A score of 1 depicts presence of a mutation whilst 0 is no mutation detected.

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank all the study participants and the field staff who helped in sample collection. We are also grateful to Prof. Kirk W. Deitsch for the pfgch1 primers provided and his technical contributions.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by funds from Musah Osei Master’s fellowship from a World Bank African Centres of Excellence Grant (ACE02-WACCBIP: Awandare). Field work for 2015-6 samples was supported by the Global Fund for Tuberculosis, AIDS and Malaria/National Malaria Control Programme, Ghana. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the funding agencies. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Müller IB, Hyde JE. Antimalarial drugs: modes of action and mechanisms of parasite resistance. Futur Microbiol. 2010; 5: 1857–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuvaniyama J, Chitnumsub P, Kamchonwongpaisan S, Vanichtanankul J, Sirawaraporn W, et al. Insights into antifolate resistance from malarial DHFR-TS structures. Nat Struct Biol. 2003; 10: 357–365. 10.1038/nsb921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang P, Read M, Sims PF, Hyde JE. Sulfadoxine resistance in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum is determined by mutations in dihydropteroate synthetase and an additional factor associated with folate utilization. Mol Microbiol. 1997; 23: 979–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks DR, Wang P, Read M, Watkins WM, Sims PF, et al. Sequence variation of the hydroxymethyldihydropterin pyrophosphokinase: dihydropteroate synthase gene in lines of the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, with differing resistance to sulfadoxine. Eur J Biochem. 1994; 224: 397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Triglia T, Cowman AF. Primary structure and expression of the dihydropteroate synthetase gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994; 91: 7149–7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowman AF, Morry MJ, Biggs BA, Cross GA, Foote SJ. Amino acid changes linked to pyrimethamine resistance in the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988; 85: 9109–9113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregson A, Plowe CV. Mechanisms of resistance of malaria parasites to antifolates. Pharmacol Rev. 2005; 57: 117–145. 10.1124/pr.57.1.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duah NO, Quashie NB, Abuaku BK, Sebeny PJ, Kronmann KC, et al. Surveillance of molecular markers of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine 5 years after the change of malaria treatment policy in Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012; 87: 996–1003. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kublin JG, Dzinjalamala FK, Kamwendo DD, Malkin EM, Cortese JF, et al. Molecular markers for failure of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and chlorproguanil-dapsone treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 2002; 185: 380–388. 10.1086/338566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plowe CV, Djimde A, Bouare M, Doumbo O, Wellems TE. Pyrimethamine and proguanil resistance-conferring mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase: polymerase chain reaction methods for surveillance in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995; 52: 565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andriantsoanirina V, Bouchier C, Tichit M, Jahevitra M, Rabearimanana S, et al. Origins of the recent emergence of Plasmodium falciparum pyrimethamine resistance alleles in Madagascar. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 2010; 54: 2323–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiara SM, Okombo J, Masseno V, Mwai L, Ochola I, et al. In vitro activity of antifolate and polymorphism in dihydrofolate reductase of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the Kenyan coast: emergence of parasites with Ile-164-Leu mutation. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 2009; 53: 3793–3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abugri J, Ansah F, Asante KP, Opoku CN, Amenga-Etego LA, et al. Prevalence of chloroquine and antifolate drug resistance alleles in Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates from three areas in Ghana [version 1; referees: awaiting peer review]. AAS Open Research. 2018; 1: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mbogo GW, Nankoberanyi S., Tukwasibwe S., et al. Temporal changes in prevalence of molecular markers mediating antimalarial drug resistance in a high malaria transmissionsetting in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014; 9: 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamour S, Melaku Y, Keus K, Wambugu J, Atkin S, et al. Malaria in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan: baseline genotypic resistance and efficacy of the artesunate plus sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine and artesunate plus amodiaquine combinations. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005; 99: 548–554. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kidgell C, Volkman SK, Daily J, Borevitz JO, Plouffe D, et al. A systematic map of genetic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2006; 2: e57 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinberg A, Siu E, Stern C, Lawrence EA, Ferdig MT, et al. Direct evidence for the adaptive role of copy number variation on antifolate susceptibility in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol. 2013; 88: 702–712. 10.1111/mmi.12162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nair S, Miller B, Barends M, Jaidee A, Patel J, et al. Adaptive copy number evolution in malaria parasites. PLoS Genet. 2008; 4: e1000243 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravenhall M, Benavente ED, Mipando M, Jensen AT, Sutherland CJ, et al. Characterizing the impact of sustained sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine use upon the Plasmodium falciparum population in Malawi. Malar J. 2016; 15: 575 10.1186/s12936-016-1634-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lozovsky ER, Chookajorn T, Brown KM, Imwong M, Shaw PJ, et al. Stepwise acquisition of pyrimethamine resistance in the malaria parasite. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2009; 106: 12025–12030. 10.1073/pnas.0905922106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown KM, Costanzo MS, Xu W, Roy S, Lozovsky ER, et al. Compensatory mutations restore fitness during the evolution of dihydrofolate reductase. Mol Biol Evol. 2010; 27: 2682–2690. 10.1093/molbev/msq160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chookajorn T, Kümpornsin K. " Snakes and Ladders" of drug resistance evolution. Virulence. 2011; 2: 244–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinberg A, Kirkman L. The molecular basis of antifolate resistance in Plasmodium falciparum: looking beyond point mutations. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2015; 1342: 10–18. 10.1111/nyas.12662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam MT, de Souza DK, Vinayak S, Griffing SM, Poe AC, et al. Selective sweeps and genetic lineages of Plasmodium falciparum drug -resistant alleles in Ghana. J Infect Dis. 2011; 203: 220–227. 10.1093/infdis/jiq038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duraisingh MT, Curtis J, Warhurst DC. Plasmodium falciparum: detection of polymorphisms in the dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthetase genes by PCR and restriction digestion. Experiment Parasitol. 1998; 89: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976; 193: 673–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kümpornsin K, Kotanan N, Chobson P, Kochakarn T, Jirawatcharadech P, et al. Biochemical and functional characterization of Plasmodium falciparum GTP cyclohydrolase I. Malar J. 2014; 13: 1–11. 10.1186/1475-2875-13-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumpornsin K, Modchang C, Heinberg A, Ekland EH, Jirawatcharadech P, et al. Origin of robustness in generating drug-resistant malaria parasites. Mol Biol Evol. 2014; 31: 1649–1660. 10.1093/molbev/msu140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naidoo I, Roper C. Mapping ‘partially resistant’, ‘fully resistant’, and ‘super resistant’ malaria. Trend Parasitol. 2013; 29: 505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hossain T, Rosenberg I, Selhub J, Kishore G, Beachy R, et al. Enhancement of folates in plants through metabolic engineering. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004; 101: 5158–5163. 10.1073/pnas.0401342101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foote SJ, Galatis D, Cowman AF. Amino acids in the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene of Plasmodium falciparum involved in cycloguanil resistance differ from those involved in pyrimethamine resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990; 87: 3014–3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson DS, Milhous WK, Wellems TE. Molecular basis of differential resistance to cycloguanil and pyrimethamine in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990; 87: 3018–3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman A, Kwarteng A, Febir LG, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei S, et al. Two years post affordable medicines facility for malaria program: availability and prices of anti-malarial drugs in central Ghana. J Pharmaceut Polic Pract. 2017; 10: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mockenhaupt FP, Teun Bousema J, Eggelte TA, Schreiber J, Ehrhardt S, et al. Plasmodium falciparum dhfr but not dhps mutations associated with sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine treatment failure and gametocyte carriage in northern Ghana. Trop Med Int Healt. 2005; 10: 901–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tahita MC, Tinto H, Erhart A, Kazienga A, Fitzhenry R, et al. Prevalence of the dhfr and dhps Mutations among Pregnant Women in Rural Burkina Faso Five Years after the Introduction of Intermittent Preventive Treatment with Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0137440 10.1371/journal.pone.0137440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cisse M, Awandare GA, Soulama A, Tinto H, Hayette M-P, et al. Recent uptake of intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine is associated with increased prevalence of Pfdhfr mutations in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2017; 16: 38 10.1186/s12936-017-1695-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kateera F, Nsobya SL, Tukwasibwe S, Hakizimana E, Mutesa L, et al. Molecular surveillance of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance markers reveals partial recovery of chloroquine susceptibility but sustained sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance at two sites of different malaria transmission intensities in Rwanda. Acta Trop. 2016; 164: 329–336. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This excel sheet contains data supporting the findings in this study. A score of 1 depicts presence of a mutation whilst 0 is no mutation detected.

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.