Abstract

It has been well established that patients with diabetes or metabolic syndrome (MetS) have increased prevalence and severity of periodontitis, an oral infection initiated by bacteria and characterized by tissue inflammation and destruction. To understand the underlying mechanisms, we have shown that saturated fatty acid (SFA), which is increased in patients with type 2 diabetes or MetS, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an important pathogenic factor for periodontitis, synergistically stimulate expression of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages by increasing ceramide production. However, the mechanisms by which increased ceramide enhances proinflammatory cytokine expression have not been well understood. Since sphingosine 1 phosphate (S1P) is a metabolite of ceramide and a bioactive lipid, we tested our hypothesis that stimulation of ceramide production by LPS and SFA facilitates S1P production, which contributes to proinflammatory cytokine expression. Results showed that LPS and palmitate, a major SFA, synergistically increased not only ceramide, but also S1P, and stimulated sphingosine kinase (SK) expression and membrane translocation in RAW264.7 macrophages. Results also showed that SK inhibition attenuated the stimulatory effect of LPS and palmitate on interleukin (IL)-6 secretion. Moreover, results showed that S1P enhanced the stimulatory effect of LPS and palmitate on IL-6 secretion. Finally, results showed that targeting S1P receptors using either S1P receptor antagonists or small interfering RNA attenuated IL-6 upregulation by LPS and palmitate. Taken together, this study demonstrated that LPS and palmitate synergistically stimulated S1P production and S1P in turn contributed to the upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression in macrophages by LPS and palmitate.

Keywords: Fatty acid, Lipopolysaccharide, Sphingosine 1 phosphate, Ceramide, Inflammation

INTRODUCTION

We reported previously that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and palmitate, a major saturated fatty acid (SFA), synergistically stimulated proinflammatory cytokine expression by increasing ceramide production in macrophages [1]. Since LPS plays an important role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis [2], a bacteria-initiated and inflammation-associated disease, and SFA is increased in patients with type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome (MetS) [3, 4], the findings from our study suggest that ceramide metabolism may play an important role in the increased prevalence and severity of periodontitis in patients with type 2 diabetes [5] or MetS [6, 7].

It has been well established that ceramide, a bioactive lipid, plays an important role in many pathobiological processes, such as growth arrest, apoptosis, cellular signaling and trafficking [8]. Studies have also shown that ceramide contributes to inflammatory signaling activation [9, 10]. However, since ceramide can be further metabolized into other sphingolipids, some of the effects of ceramide on the inflammatory signaling may be attributed to the ceramide metabolites. Therefore, it is important to determine the effect of not only ceramide, but also its metabolites on the stimulation of inflammatory signaling for better understanding the role of sphingolipid metabolism in the inflammatory response.

Ceramide is broken down by ceramidase to produce sphingosine and fatty acid, and sphingosine can be further phosphorylated by sphingosine kinase (SK) to generate S1P [11]. It is known that part of S1P is exported out of cells via transporter such as spinster homolog 2 and then bind to S1P receptors to generate “inside-out” signaling, which plays an important role in the recruitment of immune cells and other inflammatory processes [10]. It has been reported that S1P is involved in inflammation-related diseases in different animal models [12–17]. For example, Wang et al. reported that SK1 deficiency, which leads to reduced S1P, is associated with increased anti-inflammatory molecules such as IL-10 and decreased proinflammatory molecules such as TNFα and IL-6 in adipocytes of mice with high-fat diet-induced obesity [17]. However, it remains largely unknown how S1P production is upregulated by the inflammatory factors associated with diabetes or MetS and how S1P contributes to host inflammatory response.

Based on our previous findings that LPS and palmitate synergistically stimulate ceramide production in macrophages [1], we further investigated the effect of LPS and palmitate on the production of S1P and the role of S1P in the upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines by LPS and palmitate. We found that LPS and palmitate synergistically increased S1P production in macrophages by stimulating SK1 expression and that S1P in turn enhanced the stimulatory effect of LPS and palmitate on proinflammatory cytokine expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and treatment

The murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 has been used extensively in the investigations of the role of macrophages in inflammation-related diseases [18]. RAW264.7 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and grown in DMEM (ATCC, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (HyClone, Logan, UT). The cells were maintained in a 37 °C, 90% relative humidity, 5% CO2 environment. The LPS from E. coli (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was highly purified by phenol extraction and gel filtration chromatography. Palmitate was prepared by dissolving palmitic acid (Sigma) in 0.1 N NaOH and 70% ethanol at 70 °C to make 50 mM. In all experiments, unless otherwise specified, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or both 1 ng/ml of LPS and 100 μM of palmitate. S1P (Sigma) was dissolved in methanol by following the instruction from the manufacturer.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

IL-6 in medium was quantified using sandwich ELISA kits according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer (Biolegend, San Diego, CA).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA). First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized with the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using 20 μl of reaction mixture containing 0.5 μg of total RNA, 4 μl of 5× iScript reaction mixture, and 1 μl of iScript reverse transcriptase. The complete reaction was cycled for 5 minutes at 25 °C, 30 minutes at 42 °C and 5 minutes at 85°C using a PTC-200 DNA Engine (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). The reverse transcription reaction mixture was then diluted 1:10 with nuclease-free water and used for PCR amplification in the presence of the primers. The Beacon designer software (PREMIER Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA) was used for primer designing (Table 1). Primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). Real-time PCR was performed as described previously [1]. Mouse glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a control. Data were analyzed with the iCycler iQ™ software. The average starting quantity (SQ) of fluorescence units was used for analysis. Quantification was calculated using the SQ of targeted cDNA relative to that of GAPDH cDNA in the same sample.

Table 1.

The primer sequences for real-time PCR

| Genes | 5′ primer sequence | 3′ primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | TGGAGTCACAGAAGGAGTGGCTAAG | TCTGACCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCAC |

| SK1 | GGCAGTCATGTCCGGTGATG | ACAGCAGTGTGCAGTTGATGAG |

| SK2 | CACCATGAATCTTCCAAAGC | CTTGAAGGAGAATGATATTGTTG |

| S1PR1 | TTCTCATCTGCTGCTTCATCATCC | GGTCCGAGAGGGCTAGGTTG |

| S1PR2 | TTACTGGCTATCGTGGCTCTG | ATGGTGACCGTCTTGAGCAG |

| GAPDH | CTGAGTACGTCGTGGAGTC | AAATGAGCCCCAGCCTTC |

Extraction of membrane proteins

Membrane and cytosol fractions of RAW264.7 macrophages were extracted using a kit from BioVision Research Products (Mountain View, CA, USA). The protein concentration was determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Immunoblotting

Cytoplasmic and membrane protein was extracted using NE-PER™ cytoplasmic extraction kit (Pierce, Rockfold, IL). The concentration of protein was determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Thirty μg of protein from each sample was electrophoresed in a 10% polyacrylamide gel. After transferring proteins to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, immunoblotting was performed using antibodies against mouse SK1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology Inc. Danvers, MA). The proteins were visualized by incubating the membrane with chemiluminescence reagent (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA) for 1 min and exposing the membrane to x-ray films for 1–30 minutes. The X-ray films were scanned using an Epson scanner (Perfection 1200U) and the density of bands on the images was quantified using NIH Image version 1.63. For immunoblotting of S1P lyase (S1PL), cytoplasmic protein was used for electrophoresis and the immunoblot was performed using anti-S1PL antibody (MilliporeSigma, Billerica, MA).

Lipidomics

RAW264.7 macrophages were collected, fortified with internal standards, extracted with ethyl acetate/isopropyl alcohol/water (60:30:10, v/v/v), evaporated to dryness, and reconstituted in 100 μl of methanol. Simultaneous ESI/MS/MS analyses of sphingoid bases, sphingoid base 1-phosphates and ceramide were performed on a Thermo Finnigan TSQ 7000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer operating in a multiple reaction monitoring positive ionization mode. The phosphate contents of the lipid extracts were used to normalize the MS measurements of sphingolipids. The phosphate contents of the lipid extracts were measured with a standard curve analysis and a colorimetric assay of ashed phosphate [19].

Apoptosis studies

To assess cell apoptosis, mono-oligo-nucleosomes (histone-associated DNA fragments) were quantitated with the Cell Death Detection ELISA kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, RAW264.7 cells were incubated for 18 h with palmitate in the absence or presence of S1P or LPS. After the incubation, cells were lysed and the cytosol protein was transferred to the wells of a streptavidin-coated plate supplied by the manufacturer. A mixture of anti-histone-biotin and anti-DNA-peroxidase antibodies was added to the cell lysate and incubated for 2 hours. After washing, 2,2′-azinobis-3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid substrate was added to each well. Absorbance at 405 nm was measured with a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

SK activity assay

SK activity was assayed using a SK activity assay kit (Echelon, Salt Lake City, UT) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, 30 μg of protein extract were incubated in reaction buffer containing sphingosine and ATP for 1 h at 37°C and luminescence-attached ATP detector was added. Kinase activity was measured using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). All samples were prepared in triplicates and the assay was repeated at least three times.

Treatment of cells with the inhibitors of SK and S1P receptors

RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate in the absence or presence of N, N-dimethylsphingosine (DMS) (SK inhibitor), SK1-I (SK1 inhibitor), VPC23019 (S1PR1 and 3 antagonist) or JTE013 (S1PR2 antagonist) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 24 h. After the treatment, IL-6 in medium was quantified using ELISA.

RNA interference

RAW264.7 macrophages were transiently transfected with 300 nM of S1PR1 of S1PR2 small interfering RNA (siRNA) (sc-37087, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA) or scrambled control siRNA (sc-37007, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 24 h using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. After the transfection, the macrophages were treated with or without 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate for 24 h.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. ANOVA was performed to determine the statistical significance among different experimental groups. A value of P< 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

LPS and palmitate synergistically increase S1P production and stimulate sphingosine kinease

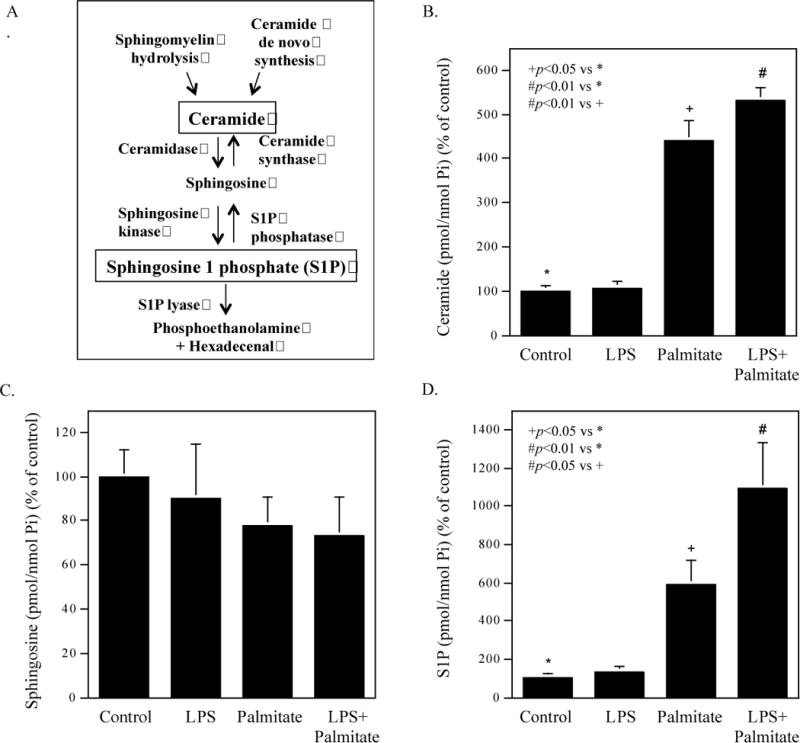

Ceramide can be broken down by ceramidase to produce sphingosine, which can be phosphorylated by SK to generate S1P (Fig. 1A). In this study, we determined the effect of LPS, palmitate or LPS plus palmitate on ceramide, sphingosine and S1P production in macrophages. Results showed that LPS had no effect on ceramide production but palmitate increased ceramide and the combination of LPS and palmitate further increased ceramide (Fig. 1B and Table 2). Results also showed that although the sphingosine level in cells treated with palmitate or the combination of LPS and palmitate appears to be less than that in control cells, the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 1C and Table 2). Furthermore, results showed that LPS had no effect on S1P production, but palmitate increased it and the combination of LPS and palmitate further increased it (Fig. 1D and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of LPS, palmitate or the combination of LPS and palmitate on production of ceramide, sphingosine and S1P. A. The metabolic pathway for S1P production. B-D. The effect of LPS, palmitate or LPS plus palmitate on the production of ceramide (B), sphingosine (C) and S1P (D). RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate for 12 h and cell lysates were subjected to lipidomic analysis to quantify ceramide (B), sphingosine (C) and S1P (D). The data presented are mean ± SD from three experiments.

Table 2.

The Effect of LPS, Palmitate or LPS plus Palmitate on the Contents of Ceramide, Sphinsosine and Sphingosine 1 Phosphate

| Ceramide | Sphingosine | Sphingosine 1 phosphate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4.73 ± 0.25 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.0021 ± 0.0006 |

| LPS | 5.06 ± 0.65 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.0028 ± 0.0003 |

| Palmitate | 20.92 ± 9.00 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.0123 ± 0.0026 |

| LPS + palmitate | 25.25 ± 7.43 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.0229 ± 0.0134 |

The data are mean ± SD of three experiments (Unit: pmol/nmol Pi)

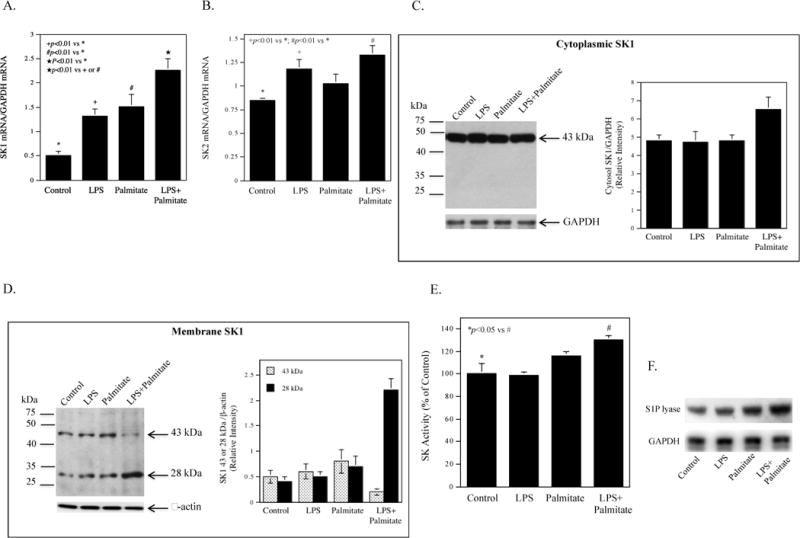

Since SK is the enzyme responsible for the phosphorylation of sphingosine, we assessed the effect of LPS and palmitate on SK isoforms SK1 and SK2 mRNA expression using real-time PCR. Results showed that while LPS or palmitate stimulated SK1 mRNA expression, the combination of LPS and palmitate further increased it (Fig. 2A). Results also showed that although LPS increased SK2 mRNA, the combination of LPS and palmitate did not further increase it (Fig. 2B), suggesting that SK2 may not be involved in the cooperative stimulation of S1P production by LPS and palmitate. In addition to SK1 mRNA, we also detected SK1 protein using immunoblotting. The immunoblot detected a SK1 protein with 43 kDa molecular weight in the cytoplasm and showed a 30% increase in this protein by the combination of LPS and palmitate, but not LPS or palmitate alone (Fig. 2C). Surprisingly, the immunoblot detected not only the 43 kDa protein, but also a protein with 28 kDa molecular weight in the cell membrane (Fig. 2D). To confirm that the 28 kDa protein is a SK1 isoform, we knocked down SK1 mRNA expression using siRNA in cells treated with LPS and palmitate, and then detected both 43 and 28 kDa proteins using immunoblotting. Results showed that SK1 mRNA knockdown led to the reduction of both 43 and 28 kDa proteins (Supplemental data, Fig. S1), supporting the notion that the 28 kDa protein is a SK1 isoform. Intriguingly, the combination of LPS and palmitate markedly increased membrane 28 kDa isoform but reduced membrane 43 kDa isoform (Fig. 2D). These results indicate that the combination of LPS and palmitate not only increased cytoplasmic SK1, but also promoted SK1 membrane translocation and cleavage, resulting in a marked increase in 28 kDa isoform. Furthermore, the SK activity assay showed that the combination of LPS and palmitate increased SK activity significantly (Fig. 2E). Since S1P is degraded by S1PL [20], we also determined the effect of LPS and palmitate on S1PL expression. Results showed that while either LPS or palmitate stimulated S1PL expression, the combination of LPS and palmitate further increased it (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Effect of LPS, palmitate or the combination of LPS and palmitate on SK1 and SK2 mRNA and protein expression. A and B. RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate for 12 h and SK1 (A) and SK2 (B) mRNA were quantified using real-time PCR. C and D. Raw264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate for 12 h and immunoblotting was performed to detect cytoplasmic (C) and membrane SK1 proteins (D). The bands of SK1 isoforms (43 kDa in the cytoplasm and 43 and 28 kDa in the membrane) were scanned, quantified and presented as mean of two blots. E. Raw264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate for 12 h and SK activity was assayed. The data presented (mean ± SD) are representative of 3 experiments with similar results. F. The effect of LPS, palmitate or LPS plus palmitate on S1P lyase protein expression. Raw264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate for 24 h and immunoblotting was performed to detect S1P lyase.

Inhibition of SK1 attenuates the stimulatory effect of LPS and palmitate on IL-6 secretion

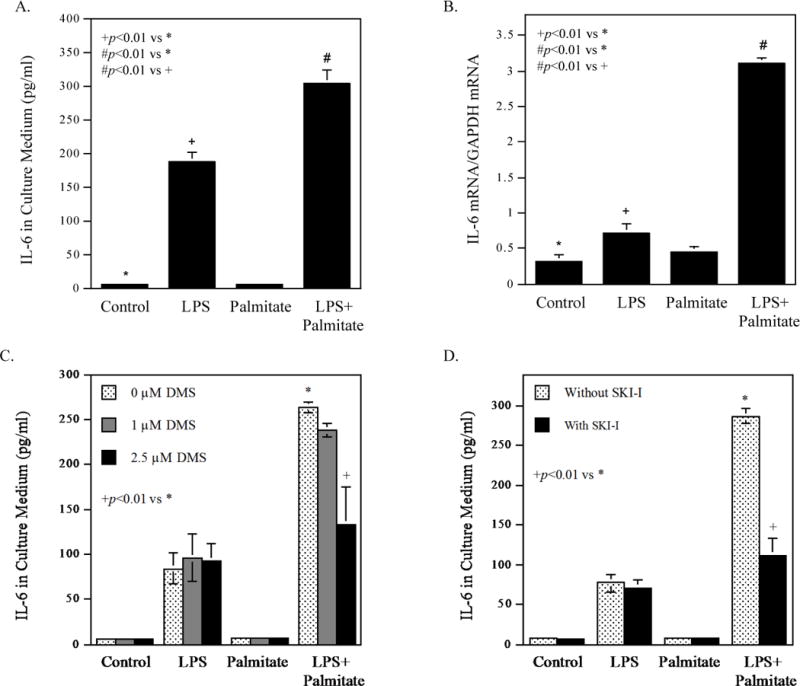

To confirm our previous report [1], we determined the combined effect of LPS and palmitate on proinflammatory gene expression. Results showed that LPS and palmitate synergistically stimulated IL-6 secretion and mRNA expression (Fig. 3A and B), and the expression of other proinflammatory genes (Table 3). We then assessed the role of S1P in the upregulation of proinflammatory genes by LPS plus palmitate by inhibiting SK activity with its pharmacological inhibitors. Results showed that N, N-dimethylsphingosine (DMS), a specific inhibitor of SK [21], significantly inhibited the stimulation of IL-6 by the combination of LPS and palmitate (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, DMS did not inhibit LPS-stimulated IL-6 secretion, which is consistent with the finding that LPS did not increase ceramide and S1P production (Fig. 1B and Fig. 1D). Furthermore, SK1-I, a SK1 selective inhibitor [22], also significantly inhibited IL-6 secretion stimulated by the combination of LPS and palmitate (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of SK activity reduces the stimulatory effect of LPS and palmitate on IL-6 secretion. A. RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate for 24 h and IL-6 in culture medium (A) and IL-6 mRNA (B) was quantified using ELISA and real-time PCR, respectively. C and D. RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate in the absence or presence of 1 or 2.5 μM of DMS (C) or 5 μM of SK1-I (D) for 24 h. After the treatment, IL-6 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. The data presented (mean ± SD) are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.

Table 3.

The Effect of LPS, Palmitate and LPS Plus Palmitate on Proinflammatory Gene Expression

| Ct | Fold increase by: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | LPS | Palmitate | LPS + palmitate | LPS | Palmitate | LPS + palmitate | |

| MCP-1 | 31.77 | 25.10 | 31.05 | 24.49 | 101.45 | 1.64 | 155.67 |

| CSF-3 | 33.30 | 31.50 | 35.31 | 28.59 | 3.48 | 0.25 | 26.13 |

| FOS | 32.03 | 31.15 | 31.88 | 29.92 | 1.84 | 1.11 | 4.31 |

| IL-6 | 30.55 | 30.39 | 29.54 | 25.86 | 1.12 | 2.04 | 25.81 |

| IL-1α | 32.79 | 29.52 | 34.14 | 27.75 | 9.65 | 0.39 | 32.99 |

| IL-1β | 33.17 | 27.48 | 33.89 | 25.76 | 51.55 | 0.61 | 170.84 |

| TNFα | 29.11 | 27.32 | 29.55 | 26.63 | 3.48 | 0.74 | 5.61 |

RAW264.7 cells were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitic acid (PA) or LPS plus PA in the absence or presence of 100 μM of DHA for 24 h and RNA was isolated from duplicate samples, combined and subjected to gene expression analysis using a Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathway-focused PCR array as described in the Methods. Full names for the abbreviations of the genes: MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; CSF3, colony stimulating factor 3; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

The effect of S1P on IL-6 expression and apoptosis regulated by LPS and palmitate

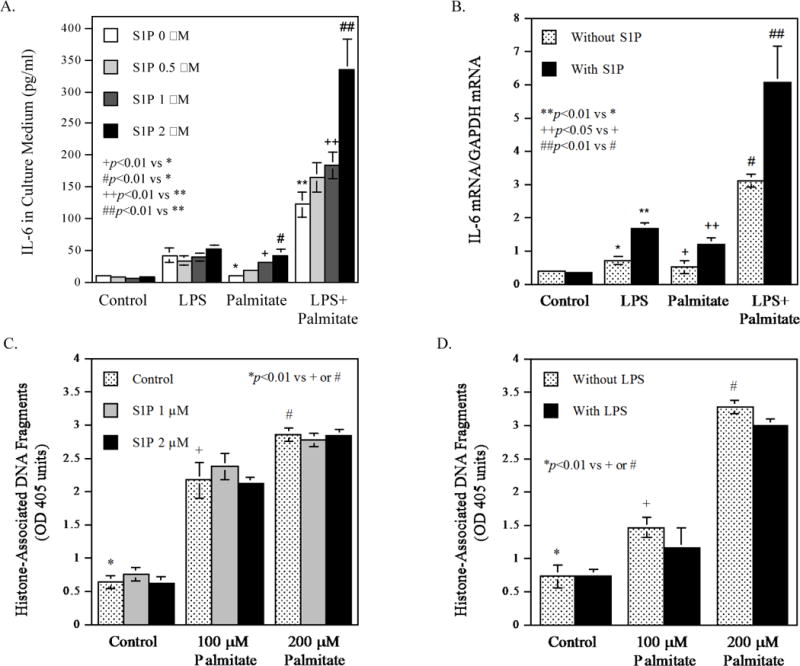

To assess the role of S1P in the upregulation of IL-6 in macrophages by LPS and palmitate, we investigated the effect of S1P on IL-6 secretion. Results showed that S1P at the physiological concentrations [23] did not stimulate IL-6 secretion by itself (Fig. 4A). However, S1P augmented the stimulatory effect of LPS plus palmitate on IL-6 secretion in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Results from our real-time PCR further demonstrated that S1P enhanced IL-6 mRNA expression stimulated by LPS, palmitate or the combination of LPS and palmitate (Fig. 4B), suggesting that S1P enhanced the effect of LPS and palmitate on the transcriptional upregulation of IL-6.

Figure 4.

The effect of S1P on IL-6 secretion and apoptosis stimulated by LPS, palmitate or the combination of LPS and palmitate. A. RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate in the absence or presence of 0.5-2 μM of S1P for 24 h. After the treatment, IL-6 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. B. RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate in the absence or presence of 2 μM of S1P for 24 h. After the treatment, IL-6 mRNA was quantified using real-time PCR. C and D. RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with 100 or 200 μM of palmitate in the absence or presence of 1 or 2 μM of S1P (C) or 1 ng/ml of LPS (D) for 24 h. After the treatment, histone-associated DNA fragments were quantified as described in Methods. The data presented (mean ± SD) are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.

Since it is known that ceramide, which is increased by palmitate (Fig. 1B), induces apoptosis but S1P suppresses ceramide-induced apoptosis [24], we determined the effect of S1P on palmitate-mediated apoptosis in RAW264.7 macrophages. Results showed that while palmitate increased apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, the addition of S1P to palmitate did not significantly reduce the degree of apoptosis induced by palmitate (Fig. 4C). Similarly, the addition of LPS to palmitate, which increases S1P (Fig. 1D), also did not attenuate the effect of palmitate on apoptosis (Fig. 4D). These findings suggest that the ceramide-induced apoptosis is dominant in cells treated with palmitate and LPS.

The interaction between S1P and its receptors is involved in the upregulation of IL-6 by LPS and palmitate

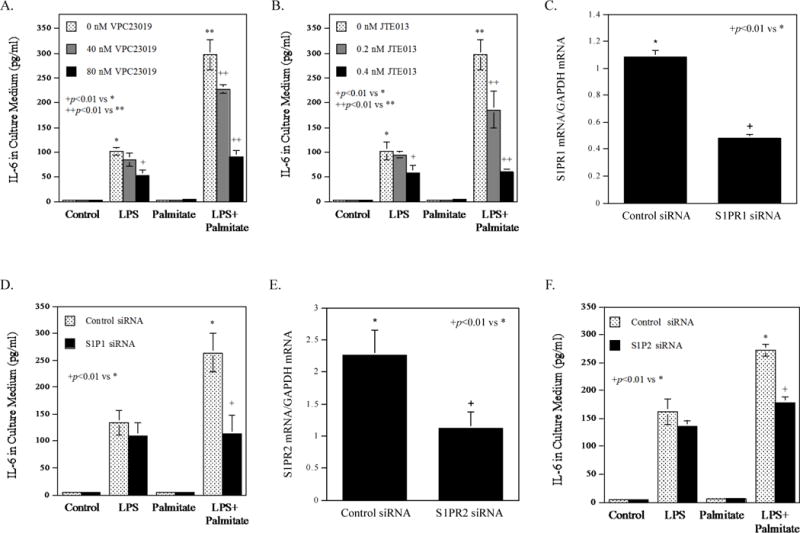

The interaction between S1P and S1P receptors (S1PR) triggers signaling activation [25]. Since it has been reported that both RAW264.7 macrophages and mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages expressed S1PR1 and S1PR2 [26] and we found that S1PR3 and S1PR4 were not upregulated by LPS, palmitate or LPS plus palmitate and S1PR5 was undetected (data not shown), we targeted S1PR1 and S1PR2. To determine which S1PR is involved in the stimulation of IL-6 secretion by LPS and palmitate, we employed VPC23019, a pharmacological antagonist for S1PR1 and S1PR3 [27], and JTE013, an antagonist for S1PR2 [28]. Results showed that both antagonists inhibited the effect of LPS or LPS plus palmitate on L-6 secretion in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5A and 5B), suggesting that both S1PR1 and S1PR2 are involved in the IL-6 upregulation by LPS or LPS plus palmitate. Furthermore, we assessed the roles of S1PR1 and S1PR2 in the stimulation of IL-6 secretion by knocking down their expression using siRNA. Results showed that S1PR1 and S1PR2 siRNA, which reduced S1PR1 and S1PR2 mRNA expression by 55% and 54%, respectively (Fig. 5C and 5E), inhibited IL-6 secretion stimulated by the combination of LPS and palmitate by 57% (Fig. 5D) and 36% (Fig. 5F), respectively.

Figure 5.

The effect of S1P receptor antagonists or S1PR1 knockdown on IL-6 secretion stimulated by LPS or the combination of LPS and palmitate. A and B. RAW264.7 macrophages were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate in the absence or presence of 40-80 nM of VPC23019 (A) or 0.2-0.4 nM of JET013 (B) for 24 h. After the treatment, IL-6 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA. C and D. RAW264.7 macrophages were transfected with control siRNA or S1PR1 siRNA for 24 h. After the transfection, S1PR1 mRNA was quantified (C). The transfected cells were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate for 24 h. After the treatment, IL-6 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA (D). E and F. RAW264.7 macrophages were transfected with control siRNA or S1PR2 siRNA for 24 h. After the transfection, S1PR2 mRNA was quantified (E). The transfected cells were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS, 100 μM of palmitate or LPS plus palmitate for 24 h. After the treatment, IL-6 in culture medium was quantified using ELISA (F). The data presented (mean ± SD) are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.

DISCUSSION

MetS is a cluster of cardiovascular risk factors including central obesity, high triglycerides, low HDL, high blood pressure, and increased glucose [29, 30]. Clinical studies in recent years have well documented that, like type 2 diabetes, MetS also exacerbates periodontitis [6, 7]. In our studies to explore the underlying mechanisms involved in type 2 diabetes- or MetS-exacerbated periodontitis, we noticed that one of the common features of dyslipidemia for type 2 diabetes and MetS is the increased saturated fatty acid (SFA) that is accompanied with hypertriglyceridemia [3]. In fact, dietary SFA is known to be a risk factor for type 2 diabetes and MetS [31]. Thus, we proposed that SFA boosts LPS signaling for proinflammatory gene expression to amplify macrophage inflammatory response to LPS. Indeed, our study showed that palmitate, the most abundant SFA in animal and human [32], and LPS synergistically stimulated proinflammatory gene expression by increasing ceramide production [1]. Since S1P is an important metabolite of ceramide, we determined the effect of LPS and palmitate on S1P production in this study.

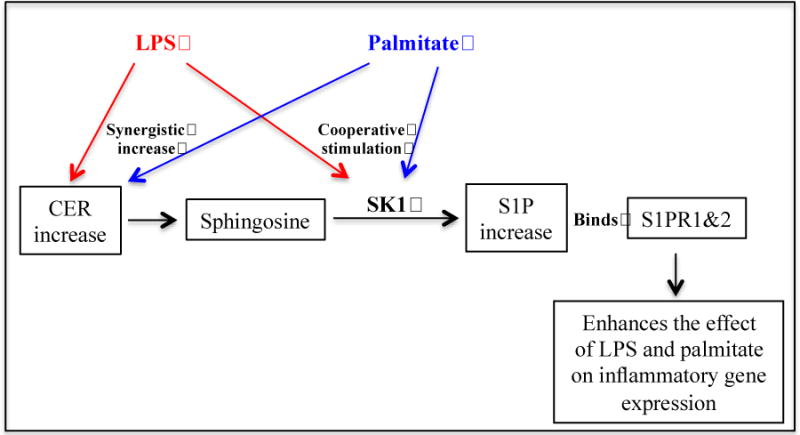

Our study showed that while LPS alone had no effect on intracellular S1P level, palmitate increased it and the combination of LPS and palmitate further increased it. To elucidate how the combination of LPS and palmitate increased S1P production, our study demonstrated that LPS and palmitate positively control two cellular mechanisms that contribute to S1P production (Fig. 6). First, LPS and palmitate increased the production of ceramide, the precursor of sphingosine and S1P. Second, LPS and palmitate cooperatively stimulated the expression and activity of SK1, which phosphorylates sphingosine to generate S1P.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram to illustrate the proposed mechanisms involved in the increased production of S1P and upregulation of inflammatory genes in macrophages. LPS and palmitate synergistically increase S1P production by increasing CER production and also SK1 expression and activity. S1P increase contributes to the upregulation of proinflammatory gene expression by interacting with S1PR1 &2.

It is known that SK1 upregulation and its membrane translocation are critical for S1P production [33]. In line with this notion, our current study showed that the combination of LPS and palmitate increased SK1 expression and activity, and membrane translocation. Our immunoblot detected the 43 kDa SK1 as the sole SK1 isoform in cytoplasm and showed a 30% increase in the 43 kDa SK1 by the combination of LPS and palmitate. However, the moderate increase in the 43 kDa SK1 protein may not be sufficient to explain how S1P production was markedly increased. It is possible, therefore, that in addition to the increase in SK1 protein expression, the combination of LPS and palmitate also stimulates SK1 enzymatic activity or increases SK2 protein/activity without increase in SK2 mRNA by posttranslational modifications. Moreover, another possible regulation for increasing S1P production is the suppression of S1P phosphatase by the combination of LPS and palmitate. Obviously, more studies are warranted to further investigate the mechanisms involved in the marked stimulation of S1P production by the combination of LPS and palmitate.

Our study demonstrated two SK1 isoforms with 43 and 28 kDa molecular weight in the cell membrane. Actually, the 43 and 28 kDa SK1 isoforms were discovered by Mizutani et al. in mouse erythroleukemia cells [34]. They further characterized 28 kDa isoform and concluded that 28 kDa molecule is likely to be cleaved from 43 kDa SK1. Interestingly, they also found that 28 kDa isoform lacked SK1 enzymatic activity. Although this finding needs to be confirmed, it is conceivable that 28 kDa isoform is a catalytically inactive fragment cleaved from 43 kDa SK1 and not involved in S1P production.

In addition to 43 and 28 kDa SK1 isoforms, other SK1 isoforms were also reported previously. For example, Kihara et al. characterized SK1 isoforms SPHK1a and SPHK1b in mouse F9 embryonal carcinoma cells [35] and Yagoub et al. demonstrated two SK1 isoforms with 43 and 51 kDa molecular weight in human breast cancer cells [36]. These studies showed the presence of SK1 isoforms under certain pathobiological conditions. However, it remains largely unknown regarding the process of SK1 cleavage and the biologic functions of the cleaved fragments.

It has been demonstrated that S1P mediates, at least in part, the inflammatory response activated by TNFα and IL-1β [33]. Our current study further provided strong evidence that S1P also mediates the inflammatory response stimulated by LPS and palmitate. First, our study showed that the inhibition with SK inhibitors suppressed the effect of LPS plus palmitate on IL-6 secretion. Second, results showed that treatment of macrophages with S1P augmented the stimulatory effect of LPS and palmitate on IL-6 secretion. Third, results also showed that targeting S1P receptors using pharmacological inhibitors or siRNA significantly reduced IL-6 secretion.

To assess the effect of S1P on the proinflammatory gene expression, we found that S1P did not directly stimulate IL-6 expression, which is consistent with the study by Yu et al. who showed that low concentration of S1P (≤ 1 μM) did not stimulate IL-6 expression in murine macrophages [15]. However, we found that S1P boosted the combined effect of LPS and palmitate on IL-6 expression in macrophages. These results suggest that S1P is capable of cross-talking with LPS and palmitate for IL-6 upregulation, which is in agreement with the previous finding that one way that S1P alters gene expression and cell functions is the crosstalk with LPS or other inflammatory mediators. For examples, studies have shown that S1P and LPS cooperate to stimulate proinflammatory gene expression in endothelial cells [37] and epithelial cells [38].

The tissue S1P concentration is controlled at low level by S1P-degrading enzymes such as S1PL [39]. It is interesting to find from the current study that LPS and palmitate had a cooperative effect on S1PL expression in macrophages (Fig. 2F). The stimulatory effect of LPS on S1PL expression in microvascular endothelial cells has been reported previously [40], and our study further demonstrated that palmitate acted similarly as LPS in stimulating S1PL expression and the combination of palmitate and LPS further stimulate S1PL expression. Although it remains unclear how the S1PL upregulaton by LPS and palmitate affects the inflammatory signaling, it is likely that the S1PL upregulation would reduce S1P content and thus attenuate S1P-enhanced inflammatory cytokine expression. It is possible that S1PL increase in response to palmitate and LPS is a cellular reaction to S1P increase, which intends to control S1P level. Further study is warranted to investigate the regulatory mechanisms involved in S1PL expression in response to LPS and palmitate and the effect of S1PL upregulation on inflammatory signaling in macrophages.

The role of S1PR1 in inflammatory response has been well established [41] and drugs targeting S1PR1 have been developed to treat inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis [42]. A recent study has shown that the S1PR1 binding molecule FTY720 inhibits osteoclast formation in rats with ligature-induced periodontitis [43]. In contrast, S1PR2 was found to often exert cellular functions that are opposed to the functions of S1PR1 [44]. To understand why S1PR1 and S1PR2 have different biological functions, studies have shown that S1PR1 and S1PR2 mainly couple to Gi and G12/13, respectively [45]. However, it has been also shown that, in addition to G12/13, S1PR2 couples to other G-proteins as well, leading to activation of multiple downstream signaling pathways including mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor kappa B cascades, which are critically involved in proinflammatory gene expression [45]. Therefore, under certain conditions, S1PR2 can act similarly as S1PR1 to stimulate inflammatory signaling. Sato et al. reported recently that the mRNA level of S1PR2, but not S1PR1 or S1PR3, was increased in advanced fibrotic liver, an inflammation-associated disorder, and the increased S1PR2 mRNA level was correlated with α-smooth muscle actin mRNA level in liver and serum alanine aminotransferase level [46]. Our current study suggests that S1PR2 acts similarly as S1PR1 to exert a crosstalk with TLR4 and fatty acid receptors to cooperatively augment proinflammatory gene expression. Since the study by Ishii et al. reported that S1PR3, S1PR4 and S1PR5 had very low expression in RAW264.7 macrophages [26], it is unlikely that these receptors would play a significant role in the upregulation of IL-6 expression by LPS and PA.

Since FCS is known to contain high levels of S1P and prolonged exposure to S1P can lead to internalization of S1P receptor, some studies pre-treated the serum with charcoal to remove S1P. However, Cao et al. reported that charcoal-stripping FCS may remove a variety of endogenous compounds, including lipids, steroid, peptide, hormones, and vitamins [47]. These authors suggested that among the effects that such changes in serum factors may induce are alterations in intracellular signaling. Therefore, we did not treat FCS with charcoal in this study as we concerned that the treatment of FCS with charcoal may remove not only S1P, but also other lipids, lipid-bound growth factors and other molecules that are important for cell growth and cell response.

In conclusion, we demonstrated in the current study that the combination of LPS and palmitate stimulated S1P production by increasing ceramide production and SK1 expression, activity and membrane translocation. Furthermore, we also demonstrated that S1P augmented the stimulatory effect of LPS and palmitate on proinflammatory gene expression in macrophages. Since it is known that MetS exacerbates periodontitis and SK1 is involved in the stimulation by LPS and palmitate of proinflammatory cytokine expression, the current study suggests that targeting SK1 may attenuate MetS-exacerbated periodontitis.

Supplementary Material

Summary Sentence.

This study shows that LPS and palmitate synergistically increase S1P production and S1P in turn contributes to the upregulation of proinflammatory genes by LPS and palmitate in macrophages.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Merit Review Grant BX000854 from Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs and NIH grant DE016353 (to Y.H.). The work on sphingolipid analysis was supported in part by the Lipidomics Shared Resource, Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina (P30 CA138313), the Lipidomics Core in the SC Lipidomics and Pathobiology COBRE (P20 RR017677) and the National Center for Research Resources and the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number C06 RR018823.

ABBREVIATIONS

- S1P

sphingosine 1 phosphate

- SK

sphingosine kinase

- S1PR

S1P receptor

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MetS

metabolic syndrome

- SFA

saturated fatty acid

- IL

interleukin

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP

YH planed the whole project; JJ, ZL, YL conducted experiments; JJ, ZL, YL, YH, MFL analyzed the data; YH wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to the final draft of the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jin J, Zhang X, Lu Z, Perry DM, Li Y, Russo SB, Cowart LA, Hannun YA, Huang Y. Acid sphingomyelinase plays a key role in palmitic acid-amplified inflammatory signaling triggered by lipopolysaccharide at low concentrations in macrophages. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E853–67. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00251.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garlet GP. Destructive and protective roles of cytokines in periodontitis: a re-appraisal from host defense and tissue destruction viewpoints. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1349–63. doi: 10.1177/0022034510376402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cascio G, Schiera G, Di Liegro I. Dietary fatty acids in metabolic syndrome, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2012;8:2–17. doi: 10.2174/157339912798829241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misra A, Singhal N, Khurana L. Obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes in developing countries: role of dietary fats and oils. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29:289S–301S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2010.10719844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mealey BL. Periodontal disease and diabetes. A two-way street. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(Suppl):26S–31S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nibali L, Tatarakis N, Needleman I, Tu YK, D’Aiuto F, Rizzo M, Donos N. Clinical review: Association between metabolic syndrome and periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:913–20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes-Filho IS, das Merces MC, de Santana Passos-Soares J, Seixas da Cruz S, Teixeira Ladeia AM, Trindade SC, de Moraes Marcilio Cerqueira E, Freitas Coelho JM, Marques Monteiro FM, Barreto ML, Pereira Vianna MI, Nascimento Costa Mda C, Seymour GJ, Scannapieco FA. Severity of Periodontitis and Metabolic Syndrome: Is There an Association? J Periodontol. 2016;87:357–66. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.150367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitatani K, Idkowiak-Baldys J, Hannun YA. The sphingolipid salvage pathway in ceramide metabolism and signaling. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1010–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modur V, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM, McIntyre TM. Endothelial cell inflammatory responses to tumor necrosis factor alpha. Ceramide-dependent and -independent mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13094–102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez-Munoz A, Presa N, Gomez-Larrauri A, Rivera IG, Trueba M, Ordonez M. Control of inflammatory responses by ceramide, sphingosine 1-phosphate and ceramide 1-phosphate. Prog Lipid Res. 2016;61:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:139–50. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geng T, Sutter A, Harland MD, Law BA, Ross JS, Lewin D, Palanisamy A, Russo SB, Chavin KD, Cowart LA. SphK1 mediates hepatic inflammation in a mouse model of NASH induced by high saturated fat feeding and initiates proinflammatory signaling in hepatocytes. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:2359–71. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M063511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorrentino R, Bertolino A, Terlizzi M, Iacono VM, Maiolino P, Cirino G, Roviezzo F, Pinto A. B cell depletion increases sphingosine-1-phosphate-dependent airway inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;52:571–83. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0207OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaghobian D, Don AS, Yaghobian S, Chen X, Pollock CA, Saad S. Increased sphingosine 1-phosphate mediates inflammation and fibrosis in tubular injury in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;43:56–66. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu H, Sun C, Argraves KM. Periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone loss induced by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is attenuated in sphingosine kinase 1-deficient mice. J Periodontal Res. 2016;51:38–49. doi: 10.1111/jre.12276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Chen Y, Li X, Zhang Y, Gulbins E, Zhang Y. Enhancement of endothelial permeability by free fatty acid through lysosomal cathepsin B-mediated Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:73229–41. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Badeanlou L, Bielawski J, Ciaraldi TP, Samad F. Sphingosine kinase 1 regulates adipose proinflammatory responses and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306:E756–68. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00549.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi HY, Daniels MP, Liu Y, Chen LY, Alsaaty S, Levine SJ, Shelhamer JH. A cytosolic phospholipase A2-initiated lipid mediator pathway induces autophagy in macrophages. J Immunol. 2011;187:5286–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Veldhoven PP, Bell RM. Effect of harvesting methods, growth conditions and growth phase on diacylglycerol levels in cultured human adherent cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1988;959:185–96. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar A, Saba JD. Lyase to live by: sphingosine phosphate lyase as a therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:1013–25. doi: 10.1517/14728220903039722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edsall LC, Van Brocklyn JR, Cuvillier O, Kleuser B, Spiegel S. N,N-Dimethylsphingosine is a potent competitive inhibitor of sphingosine kinase but not of protein kinase C: modulation of cellular levels of sphingosine 1-phosphate and ceramide. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12892–8. doi: 10.1021/bi980744d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madhunapantula SV, Hengst J, Gowda R, Fox TE, Yun JK, Robertson GP. Targeting sphingosine kinase-1 to inhibit melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25:259–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2012.00970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kowalski GM, Carey AL, Selathurai A, Kingwell BA, Bruce CR. Plasma sphingosine-1-phosphate is elevated in obesity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuvillier O, Pirianov G, Kleuser B, Vanek PG, Coso OA, Gutkind S, Spiegel S. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature. 1996;381:800–3. doi: 10.1038/381800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aoki M, Aoki H, Ramanathan R, Hait NC, Takabe K. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Signaling in Immune Cells and Inflammation: Roles and Therapeutic Potential. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:8606878. doi: 10.1155/2016/8606878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishii M, Egen JG, Klauschen F, Meier-Schellersheim M, Saeki Y, Vacher J, Proia RL, Germain RN. Sphingosine-1-phosphate mobilizes osteoclast precursors and regulates bone homeostasis. Nature. 2009;458:524–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao R, Hoover HE, Zhang J, Honbo N, Alano CC, Karliner JS. Cardiomyocyte S1P1 receptor-mediated extracellular signal-related kinase signaling and desensitization. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;53:486–94. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181a7b58a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wamhoff BR, Lynch KR, Macdonald TL, Owens GK. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor subtypes differentially regulate smooth muscle cell phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1454–61. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C, American Heart, A., National Heart, L., Blood, I Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC, Jr, International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federtion; International Atherosclerosis Society; International Association for the Study of Obesity Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips CM, Goumidi L, Bertrais S, Field MR, McManus R, Hercberg S, Lairon D, Planells R, Roche HM. Dietary saturated fat, gender and genetic variation at the TCF7L2 locus predict the development of metabolic syndrome. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:239–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kageyama A, Matsui H, Ohta M, Sambuichi K, Kawano H, Notsu T, Imada K, Yokoyama T, Kurabayashi M. Palmitic acid induces osteoblastic differentiation in vascular smooth muscle cells through ACSL3 and NF-kappaB, novel targets of eicosapentaenoic acid. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snider AJ, Orr Gandy KA, Obeid LM. Sphingosine kinase: Role in regulation of bioactive sphingolipid mediators in inflammation. Biochimie. 2010;92:707–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizutani N, Kobayashi M, Sobue S, Ichihara M, Ito H, Tanaka K, Iwaki S, Fujii S, Ito Y, Tamiya-Koizumi K, Takagi A, Kojima T, Naoe T, Suzuki M, Nakamura M, Banno Y, Nozawa Y, Murate T. Sphingosine kinase 1 expression is downregulated during differentiation of Friend cells due to decreased c-MYB. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:1006–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kihara A, Anada Y, Igarashi Y. Mouse sphingosine kinase isoforms SPHK1a and SPHK1b differ in enzymatic traits including stability, localization, modification, and oligomerization. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4532–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yagoub D, Wilkins MR, Lay AJ, Kaczorowski DC, Hatoum D, Bajan S, Hutvagner G, Lai JH, Wu W, Martiniello-Wilks R, Xia P, McGowan EM. Sphingosine kinase 1 isoform-specific interactions in breast cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:1899–915. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez-Pisonero I, Duenas AI, Barreiro O, Montero O, Sanchez-Madrid F, Garcia-Rodriguez C. Lipopolysaccharide and sphingosine-1-phosphate cooperate to induce inflammatory molecules and leukocyte adhesion in endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2012;189:5402–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eskan MA, Rose BG, Benakanakere MR, Zeng Q, Fujioka D, Martin MH, Lee MJ, Kinane DF. TLR4 and S1P receptors cooperate to enhance inflammatory cytokine production in human gingival epithelial cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1138–47. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saba JD, de la Garza-Rodea AS. S1P lyase in skeletal muscle regeneration and satellite cell activation: exposing the hidden lyase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y, Gorshkova IA, Berdyshev E, He D, Fu P, Ma W, Su Y, Usatyuk PV, Pendyala S, Oskouian B, Saba JD, Garcia JG, Natarajan V. Protection of LPS-induced murine acute lung injury by sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase suppression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:426–35. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0422OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Sullivan C, Dev KK. The structure and function of the S1P1 receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guerrero M, Urbano M, Roberts E. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 agonists: a patent review (2013-2015) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2016;26:455–70. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2016.1157165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee DE, Kim JH, Choi SH, Cha JH, Bak EJ, Yoo YJ. The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 binding molecule FTY720 inhibits osteoclast formation in rats with ligature-induced periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2017;52:33–41. doi: 10.1111/jre.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blankenbach KV, Schwalm S, Pfeilschifter J, Meyer Zu Heringdorf D. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor-2 Antagonists: Therapeutic Potential and Potential Risks. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:167. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skoura A, Hla T. Regulation of vascular physiology and pathology by the S1P2 receptor subtype. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:221–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato M, Ikeda H, Uranbileg B, Kurano M, Saigusa D, Aoki J, Maki H, Kudo H, Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Yatomi Y. Sphingosine kinase-1, S1P transporter spinster homolog 2 and S1P2 mRNA expressions are increased in liver with advanced fibrosis in human. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32119. doi: 10.1038/srep32119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao Z, West C, Norton-Wenzel CS, Rej R, Davis FB, Davis PJ, Rej R. Effects of resin or charcoal treatment on fetal bovine serum and bovine calf serum. Endocr Res. 2009;34:101–8. doi: 10.3109/07435800903204082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.