Abstract

Substance use is embedded within the sociocultural and identity-related experiences of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. However, assessments of their substance use often obscure these foundations. Latent class analysis was used to examine how patterns of substance use represent the social, economic, and identity-related experiences of gay and bisexual men. Participants were sexually-active gay and bisexual men (including other men who have sex with men), aged ≥16 years, living in Metro Vancouver (n = 774). LCA indicators included all substances used in the past six months self-reported by more than 30 men. Model selection was made with consideration to model parsimony, interpretability and optimisation of statistical criteria. Multinomial regression identified factors associated with class membership. A six-class solution was identified representing: ‘assorted drug use’ (4.5%), ‘club drug use’ (9.5%), ‘street drug use’ (12.1%), ‘sex drug use’ (11.4%), ‘conventional drug use’ (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, marijuana; 25.9%) and ‘limited drug use’ (36.7%). Factors associated with class membership included age, sexual orientation, annual income, occupation, income from drug sales, housing stability, group sex event participation, gay bars/clubs’ attendance, sensation seeking and escape-motive. These results highlight the need for programmes and policies that seek to lessen social disparities and account for social distinctions among this population.

Keywords: substance use, gay and bisexual men, community, identity, latent class analysis, Canada

Introduction

From aphrodisiacs to chemsex, drugs have long played an important role in shaping sexuality (Sandroni 2001). Among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, substance use has always been entwined with contemporary gay communities. Indeed, gay-centric neighbourhoods like Greenwich Village in New York and the Castro in San Francisco were historically zoned for what was termed “deviant entertainment” – a euphemism for bohemian activities of the countercultural era (Bérubé 2003; Israelstam and Lambert 1984). As gay-friendly businesses began to flourish in these neighbourhoods, bars, clubs and bathhouses emerged as touchstones of Western gay life — and substance use with them.

Indeed, gay identity and community connectedness have previously been associated with elevated drug use among gay and bisexual men (Carpiano et al. 2011) and qualitative studies have repeatedly explored the rationale for gay and bisexual men’s use of various drugs – noting the fundamental role they play in both helping gay and bisexual men cope with minority stress and in facilitating social bonding (Ahmed et al. 2016; Weatherburn et al. 2017; McKay et al. 2012). For these individuals, substance use may be “suffused with romantic, emotional and communal attachments” (Amaro 2016, 255) – illustrating the nuanced and sometimes beneficial, aspects of substance use. In support, recent quantitative work has shown that party-and-play (PnP) drug users report higher levels of resilience, lower levels of perceived stigma and greater social connectedness to other gay and bisexual men and people living with HIV (Power et al. 2018).

Theoretical Framework

To articulate the association between substance use and broader socio-cultural phenomena, we used Bourdieu’s Field Theory (Bourdieu 1984), which identifies individual tastes, preferences and behaviours as the by-product of social and cultural norms (Bourdieu 1984). The resultant social environments created by these norms are particularly important when examining patterns of substance use or other illegal or stigmatised behaviours. Indeed, the “law constantly registers a state of power relations” (Bourdieu 1986, 817) and places demanding social sanctions on those who violate its codices. In Bourdieu’s words, “symbolic goods” such as those which contour the social mores of drug use, “are the ideal weapon in strategies of social distinction” (Bourdieu 1984, 59); and in the case of drug use, each substance is a battlefield for social symbolism (Room 2005; McKay et al. 2012).

Among the first and most notable attempts to apply Bourdieu’s Field Theory to the drug trade, Bourgois (2003) provides striking ethnography showing how macro-socioecomic and cultural shepherd Puerto Rican men in New York City’s Upper East Side into “El Barrio” street culture – a world engulfed in drugs and violence at the height of the crack epidemic (Bourgois 2003). In doing so, Bourgois highlights how key social, economic and identity-related factors mould individual’s preferences, behaviours and beliefs. More recently, ethnographers have described how some gay and bisexual men use drugs to cope with social marginalisation and find belonging among, so called, like-minded individuals. Such a perspective allows us to sidestep the fallacy of viewing taboo health behaviours as merely moral failing or the product of miscalculated risk assessment. For instance, Ahmed (2016) describes how social norms and perceptions of ubiquity reinforce sexual permissions, expectations and social boundaries associated with South London’s chemsex culture. Qualitative research such as theirs highlights substance use as a form of social and cultural capital that allows individuals to cope and survive – even while engaging in what some would describe as unhealthy and illicit behaviour. Indeed, while some substances are thought of as “prestige commodities” (e.g., champagne), other drugs are often stigmatised and the people who use them are often ostracised by the mainstream (Room 2005). According to Field Theory, this process of social distinction gives rise to the phenomenon of substance-use sub-cultures which are widely documented in the qualitative literature (Amaro 2016; Room 2005; McKay et al. 2012), but have not been often explored in quantitative studies. Thus, identifying key social, economic and identity-related factors that condition and reinforce patterns of drug use among gay and bisexual men is expected to improve our understanding of how individuals use drugs to derive pleasure, deal with social stigma and navigate through their social worlds.

Objectives and Hypotheses

We hypothesised that gay and bisexual men combine distinct sexual practices and substance use patterns to cope with their social marginalisation and facilitate in-group bonding. Exploring this hypothesis, the present study used latent class analysis (LCA) to describe the social underpinnings of these substance use patterns by examining the social, economic and identity-related factors associated with distinct patterns of substance use among gay and bisexual men.

METHODS

Study Protocol

Data for this cross-sectional study were collected through the Momentum Health Study, a bio-behavioural cohort study based in Metro Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Details regarding this cohort have been previously published (Lachowsky et al. 2016; Moore et al. 2016). In short, respondent driven-sampling (RDS; Heckathorn 1997) was used to recruit participants between February 2012 and February 2015. Inclusion criteria included those who: (i) received a valid invitation to participate in the RDS study; (ii) self-identified as a man (including trans men); (iii) were 16 years or older; (iv) reported having had sex with a man in the previous six months; (v) resided in the Metro-Vancouver area; (vi) were able to provide voluntary written informed consent; and (vii) were able to complete a computer administered questionnaire in English. At each study visit, respondents completed a computer-administered questionnaire assessing demographic, psychosocial and bio-behavioural factors related to substance use and sexual behaviour; followed by a brief nurse-administered questionnaire and testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Respondents received a $50 CAD honorarium and $10 CAD for each eligible referral they recruited into the study. Follow-up visits occurred at six-months intervals. Ethics approval for this study was granted by the research ethics boards at Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and the University of Victoria.

Variables

Dependent Variables (Latent Class Indicators)

Any use in the past six months (P6M) of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, erectile dysfunction drugs (EDD), poppers, crack, cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, speed, gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), benzodiazepine, ecstasy, ketamine, mushrooms, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), heroin, codeine, oxycodone, steroids and nitrous oxide was measured.

Explanatory Variables (Latent Class Covariates)

Demographic factors included age, ethnicity, sexual orientation and self-reported HIV status. Variables assessing a participant’s socioeconomic status included their annual income, employment status, formal educational attainment, current housing situation and sources of other income (i.e., welfare, employment insurance, Canadian Pension Plan, personal savings, loans, disability benefit, sex work, drug sales). Participants also reported their occupation, which was coded by two reviewers as “out of work” (e.g., unemployed), “working class” (e.g., retail, restaurant, entertainment, customer service, construction, home repair, landscaping, interior remodelling, labour), or “professional class” (e.g., management, finance, administration, health care, research, education, social work, civil service). Community connectedness factors measured whether respondents recently (i.e., in the P6M) attended gay groups or meetings, read gay newspapers, visited gay bars or clubs, participated in gay sports teams, used gay smartphone apps and/or internet sites to find sexual partners, or attended a group sex event. We also assessed where respondents lived (i.e., downtown Vancouver, elsewhere in the City of Vancouver, outside the City of Vancouver), whether they went to the most recent pride parade and if they had recently (P6M) and ever tested for HIV. Distinct from community connectedness (Frost and Meyer 2012), social attachment was assessed based on a respondent’s relationship status, the proportion of their social time spent with other gay men and the gender of the people they socialise with. The Lubben Social Network Scale (Lubben et al. 2006) was used to characterise social support using 3 items (e.g., How many of your friends do you see or hear from at least once a month?”). Scores ranged from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating a larger social support network. Additionally, to contextualise coping related substance use and the confounding bias of mental health problems, several scales were used to assess cognitive well-being: the Self-Esteem Scale (Herek and Greene 1995) assessed low self-esteem using 7 Likert-items. Scores ranged from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating lower self-esteem. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Snaith 2003) assessed anxiety (e.g., “Worrying thoughts go through my mind”) and depression (e.g., “I feel as if I am slowed down”) using two subscales assessing agreement with relevant scale items. Scores on each subscale ranged from 0 to 21, with scores >10 indicating abnormal anxiety/depression symptoms and scores between 8 and 10 indicating borderline clinical symptoms. Event-level individual and partner substance use (within 2 hours prior to or during sex) of alcohol, marijuana, EDD, poppers, injection drugs and other drugs was also assessed for a participant’s most recent sexual experience with up to five of their most recent sexual partners. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (Saunders et al. 1993) assessed alcohol-related problems using 10 Likert-items (e.g., “How often during the last year have you needed a first drink in the morning to get yourself going after a heavy drinking session?”). Scores ranged from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating increased likelihood and seriousness of alcohol use problems. The Escape Motive Scale (McKirnan et al. 2001) assessed the extent to which individuals feel drug use reduces their sexual inhibitions using 12 Likert-items (e.g., “Being drunk makes me more comfortable sexually”). Scores ranged from 12 to 48, with higher scores indicating greater escape motivation. Finally, measures related to sexual behaviour assessed the number of male anal sex partners in the P6M, whether participants had engaged in condomless anal sex with a serodiscordant or unknown-status partner, their anal sex positioning preference and whether they had engaged in any of the following behaviours in the P6M: anal sex, oral sex, rimming, masturbation, fisting and sex toy use. The Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale (Kalichman and Rompa 1995) assessed sexual thrill-seeking tendencies using 11 Likert-items (e.g., “I like to have new and exciting sexual experiences and sensations”). Scores ranged from 11 to 44, with higher scores indicating greater sexual sensation seeking.

Statistical Analysis

Latent Class Analysis

LCA was used to identify patterns of substance use by including all substances that were reportedly used by more than 30 respondents at enrolment. LCA is a person-centred analytic approach that identifies underlying patterns of covariance in the data structure to identify “classes” or subgroups of participants. To select the number of latent classes in our LCA model, several information criteria were reviewed (i.e., Akaike Information Criterion [AIC], Corrected AIC, Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC] and adjusted BIC). BIC and adjusted BIC are the favoured information criteria for selecting the number of classes in an LCA model (Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén 2007) – though a number of factors influence their performance (Dziak and Donna 2012; Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén 2007). For example, BIC has been shown to be less sensitive to complex models with unequal class sizes – thus underestimating the number of classes; and AIC has been shown to regularly overestimate the number of classes as it is not sample size adjusted (Lin and Dayton 1997; Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén 2007; Yang and Yang 2007). Additionally, unless LCAs are sufficiently powered, the risk for underestimating (rather than overestimating) the number of classes is generally higher (Dziak and Donna 2012). Therefore, in addition to the parsimony, interpretability and theoretical appropriateness of each potential model, the number of latent classes in the present study was selected using the adjusted Baysian information criterion. To describe each latent class, row and table comparisons were subjectively assessed to identify substance use patterns representative of their overall composition.

Covariate Analysis

In a three-step LCA, proportional assignment was used for determining class membership (Dias and Vermunt 2008). This soft-partitioning method involves creating a number of records equal to the number of selected classes for each participant and setting the values of each record equal to the posterior probability that a given participant will belong to each of the identified classes. Multinomial logistic regression models are then used to calculate bivariable and multivariable odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for psychosocial and identity-related factors correlated with latent class membership and to provide additional details regarding class composition (i.e., sexual behaviour and event-level substance use). The final multivariable multinomial logistic regression model was then fit using a backwards selection procedure to identify the most salient associations. This was done by including all variables of theoretical interest (i.e., HIV-status, demographic factors, socioeconomic indicators and variables relating to community/social connectedness) and psychosocial confounder variables (i.e., sensation seeking, escape motivation, anxiety, depression and self-esteem) with univariable p-values <0.20 and then omitting the covariate with the highest Type-III p-value in a stepwise fashion until the AIC score was optimised. All analyses were conducted in SAS v.9.4. Interpretations of statistical significance was based on α = 0.05.

Results

Descriptive Results

Sample Description

A total of 774 men were recruited into the Momentum Health Study. The median age of the sample was 34 years (Q1, Q3: 26, 47). Most men identified as gay (84.6%) versus bisexual (9.4%); were White (75.6%) and were single (61.6%). Most men reported annual incomes <$30,000 CAD (62.7%), 76.9% had some post-secondary education, 63.4% were employed and 87.3% were stably housed. Other income sources included welfare (25.1%), Employment Insurance (5.6%), Canadian Pension earnings (8.4%), disability benefit (6.6%), savings (19.1%), loans (6.9%), sex work (7.0%) and drug sales (3.9%). Most men engaged in receptive (67.7%) and insertive anal sex (71.5%) and 25.7% reported attending a group sex event in the P6M. Participants also reported connecting to the gay community over the previous six months by: reading gay newspapers (82.7%), attending gay bars/clubs (79.7%), attending gay groups or meetings (38.8%), attending the most recent annual gay pride event (62.8%), seeking partners on gay apps (54.4%) and websites (63.1%) and spending >50% of their social time with other gay or bisexual men (50.2%).

Substance Use Prevalence

Table 1 provides the period prevalence of each substance used and the proportion of individuals reporting greater than weekly use over the P6M. The most commonly reported substances were alcohol (85.9%), tobacco (43.8%), marijuana (61.1%) and poppers (37.6%). Approximately a quarter of respondents reported using cocaine (25.8%), ecstasy (25.2%), EDD (24.2%), crystal methamphetamine (19.9%) and GHB (19.0%). Similarly, participant’s event-level substance use within 2 hours of a recently reported sexual event was high: 58.5% reported drinking alcohol, 35.5% reported marijuana use, 16.6% reported EDD use, 29.2% reported poppers use and 25.9% reported using other drugs.

Table 1.

Reported Substance Use

| Any P6M Use | If yes, at least weekly use? (of those used) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Stimulants | ||||

| Crack | 74 | 9.6 | 4 | 5.4 |

| Cocaine | 200 | 25.8 | 6 | 3.0 |

| Prescription Stimulants | 50 | 6.5 | 9 | 18.0 |

| Crystal meth | 154 | 19.9 | 32 | 20.8 |

| Speed | 46 | 5.9 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Poppers | 291 | 37.6 | 30 | 10.3 |

| Depressants | ||||

| Alcohol | 660 | 85.9 | 257 | 38.9 |

| Gamma-hydroxybutyrate | 147 | 19.0 | 10 | 6.8 |

| Benzodiazepine | 42 | 5.4 | 5 | 11.9 |

| Barbiturates | 7 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hallucinogens | ||||

| Ecstasy | 197 | 25.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Ketamine | 105 | 13.6 | 3 | 2.9 |

| Mushrooms | 86 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Lysergic acid diethylamide | 34 | 4.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Nitrous Oxide | 8 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Others | 26 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Opioids | ||||

| Heroin | 31 | 4.0 | 6 | 19.4 |

| Morphine | 13 | 1.7 | 2 | 15.4 |

| Codeine | 44 | 5.7 | 3 | 6.8 |

| Oxycodone | 39 | 5.0 | 5 | 12.8 |

| Others | 19 | 2.5 | 5 | 26.3 |

| Cannabinoids | ||||

| MarijuanaA | 473 | 61.1 | 195 A | 45.8 A |

| Other Drugs | ||||

| TobaccoB | 339 B | 43.8 B | 188 B | 44.1 B |

| Erectile Dysfunction Drugs | 187 | 24.2 | 7 | 3.7 |

| Steroids | 42 | 5.4 | 8 | 19.0 |

| Others | 45 | 5.8 | 18 | 40.0 |

Over Past Three Months

Daily vs. Regularly/Occasionally

LCA Results

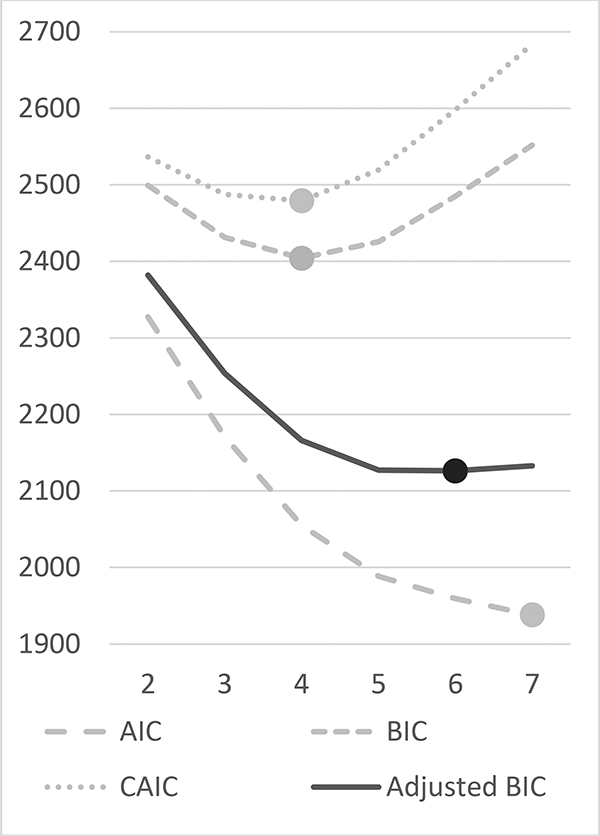

Figure 1 shows that the adjusted-BIC was optimised at a six-class solution. Consistent with this, a six-class solution was selected. Supplemental Table S1 shows the posterior probability loadings for class membership based on assigned classes. The prevalence of substance use in each class and the overall distribution of class assignments are reported in Table 2; Supplemental Table S3 provides the univariate associations between each explanatory factor and class membership and Table 3 provides the final multivariable models for class membership.

Figure 1.

Information Criterion values used in model specification.

Table 2.

Six-class LCA model Probability Loadings

| Class Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class Names | Limited Drug Use |

Conventional Drug Use |

Sex Drug Use |

Club Drug Use |

Street Drug Use |

Assorted Drug Use |

| Distribution | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| 296 (36.7) | 203 (25.9) | 90 (11.4) | 69 (9.5) | 82 (12.1) | 34 (4.5) | |

|

Probability Loadings |

% | % | % | % | % | % |

| Alcohol | 75.6 | 100.0 | 84.3 | 98.6 | 75.8 | 92.9 |

| Marijuana | 29.6 | 79.7 | 74.0 | 90.2 | 70.1 | 93.2 |

| Tobacco | 23.2 | 43.1 | 47.0 | 69.1 | 69.9 | 84.9 |

| Erectile Drugs | 10.9 | 22.2 | 78.0 | 8.5 | 14.7 | 66.8 |

| Poppers | 20.1 | 36.9 | 74.8 | 51.9 | 32.7 | 73.7 |

| Crack | 0.7 | 0.0 | 14.5 | 3.2 | 39.1 | 58.6 |

| Cocaine | 0.9 | 15.2 | 44.6 | 72.5 | 44.1 | 96.3 |

| Crystal | 1.3 | 5.0 | 77.2 | 2.3 | 38.7 | 100.0 |

| Speed | 0.0 | 0.6 | 6.5 | 16.6 | 10.9 | 48.0 |

| GHB | 0.6 | 2.0 | 86.5 | 33.4 | 13.3 | 81.7 |

| Benzo | 1.1 | 1.6 | 6.1 | 10.1 | 10.6 | 37.6 |

| Ecstasy | 0.0 | 20.2 | 65.7 | 89.1 | 4.8 | 83.3 |

| Ketamine | 0.0 | 2.7 | 41.3 | 43.2 | 0.0 | 91.2 |

| Mushrooms | 0.0 | 14.9 | 5.1 | 51.7 | 1.4 | 36.5 |

| LSD | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 26.5 | 4.2 | 30.7 |

| Heroin | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.9 | 35.8 |

| Codeine | 2.4 | 1.2 | 5.7 | 3.6 | 15.8 | 35.9 |

| Oxycodone | 0.0 | 1.5 | 7.5 | 5.9 | 13.9 | 34.8 |

| Rx Steroids | 2.8 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 6.2 | 10.4 |

Note: BOLD indicates ⩾ 50%

Table 3.

Multivariable adjusted associations of LCA class membership with Limited Drug Use as the Referent Class

| Assorted Drug Use | Street Drug Use | Club Drug Use | Sex Drug Use | Conventional Drug Use |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | aOR (95%CI) | |

| Age | 0.95 (0.91, 0.99) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | 0.93 (0.89, 0.96) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) |

| Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale | 1.13 (1.02, 1.26) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.11) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.23) | 1.12 (1.04, 1.20) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.09) |

| Escape Movie Scale | 1.07 (1.00, 1.14) | 1.09 (1.05, 1.15) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) |

| Non-Gay Identified | 2.97 (1.14, 7.72) | 3.16 (1.63, 6.10) | 1.86 (0.85, 4.08) | 1.22 (0.51, 2.90) | 1.48 (0.82, 2.68) |

| Self-Reported HIV-Positive | 5.97 (2.18, 16.34) | 1.75 (0.92, 3.32) | 0.73 (0.24, 2.22) | 3.98 (2.07, 7.65) | 1.03 (0.61, 1.74) |

| Annual Income ⩾ $30,000 | 1.06 (0.41, 2.79) | 0.77 (0.39, 1.50) | 1.15 (0.62, 2.12) | 2.92 (1.59, 5.35) | 0.94 (0.62, 1.42) |

| Stably Housed | 0.23 (0.08, 0.63) | 0.29 (0.14, 0.59) | 1.46 (0.42, 5.04) | 0.66 (0.27, 1.62) | 0.77 (0.38, 1.57) |

| Occupation | |||||

| Out of Work | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Professionals/Upper Class | 0.58 (0.20, 1.75) | 0.30 (0.15, 0.61) | 0.59 (0.28, 1.26) | 0.41 (0.20, 0.83) | 0.97 (0.57, 1.67) |

| Working Class/Lower Class | 1.04 (0.39, 2.76) | 0.42 (0.22, 0.81) | 0.62 (0.29, 1.32) | 0.57 (0.28, 1.15) | 1.21 (0.71, 2.06) |

| Income from Drug Sales in P6M | 19.77 (3.65, 106.89) | 2.12 (0.32, 14.2) | 6.51 (1.11, 38.29) | 9.24 (1.72, 49.8) | 2.17 (0.39, 12.04) |

| Attended Group Sex Events in P6M | 3.26 (1.39, 7.63) | 0.77 (0.4, 1.49) | 0.77 (0.38, 1.58) | 2.41 (1.34, 4.31) | 1.22 (0.77, 1.94) |

| Attend Gay-Bars/Clubs in P6M | 0.79 (0.33, 1.88) | 1.02 (0.56, 1.86) | 4.37 (1.56, 12.26) | 0.89 (0.47, 1.69) | 2.32 (1.37, 3.92) |

aOR = adjusted odds ratio; 95%CI = 95% confidence interval; P6M = Past Six Months BOLDED statistics indicates statistical significance at p ⩽ 0.05. Variables included but not selected via backwards selection were: Self-esteem Scale scores, HAD Anxiety and Depression scores, Social Support scores, ethnicity, neighbourhood, income from welfare, educational attainment, income from disability, income from loans, reading gay newspapers, sex seeking via apps, sex seeking via websites, amount of social time spent with other gay or bisexual men, gay pride parade attendance, and social group gender composition.

Class 1: Limited Drug Use

Class 1, representing 36.7% of respondents, was characterised by limited alcohol use compared to all other classes. Indeed, individuals in this class had lower probabilities of alcohol use (75.6%), tobacco use (23.2%) and marijuana use (29.6%) relative to those in other classes. Based on these lower levels of substance use, this class was selected as the referent class for multivariable modelling.

Class 2: Conventional Drug Use

Class 2 represents 25.9% of respondents. Membership in this class was characterised by recent use of alcohol (100.0%), marijuana (79.7%) and tobacco (43.1%). Along with the limited drug use class, men in this class exhibited low probabilities of reporting use of other drugs. Multivariable results comparing men in this class to those in the limited drug use class (i.e., the referent class) suggested that men in this class were more likely to attend gay bars and clubs (aOR = 2.32, 95%CI = [1.37, 3.92]), but otherwise there were no significant differences.

Class 3: Sex Drug Use

Class 3, representing 11.4% of respondents, was characterised by recent use of GHB (86.5%), alcohol (84.3%), EDD (78.0%), crystal methamphetamine (77.2%), poppers (74.8%), marijuana (74.0%) and ecstasy (65.7%). Compared with men in the limited drug use class, multivariable results suggested that men in this class had higher sensation seeking (aOR = 1.12, 95%CI = [1.04, 1.20]) and escape motivation (aOR = 1.08, 95%CI = [1.03, 1.13]); were more likely to self-report as HIV-positive (aOR = 3.98, 95%CI = [2.07, 7.65]), to make more than $30,000 CAD (aOR = 2.92, 95%CI = [1.59, 5.35]), to report income from drug sales (aOR = 9.24, 95%CI = [1.72, 49.80]) and to report recent group sex event participation (aOR = 2.41, 95%CI = [1.34, 4.31]); and were less likely to report a professional-class occupation (vs. out of work; aOR = 0.41, 95%CI = [0.20, 0.83]).

Class 4: Club Drug Use

Class 4, representing 9.5% of respondents, was characterised by recent use of alcohol (98.6%), marijuana (90.2%), ecstasy (89.1%), cocaine (72.5%), tobacco (69.1%), poppers (51.9%) and mushrooms (51.7%). Reported use of sex drugs was relatively lower than the previous class. Compared with men in the limited drug use class, multivariable results suggested that men in this class were younger (aOR = 0.93, 95%CI = [0.89, 0.96]); had higher sensation seeking (aOR = 1.14, 95%CI = [1.06, 1.23]); and were more likely to report income from drug sales (aOR = 6.51, 95%CI = [1.11, 38.29]) and to have visited gay bars and clubs in the P6M (aOR = 4.37, 95%CI = [1.56, 12.26]).

Class 5: Street Drug Use

Class 5, representing 12.1% of respondents, was characterised by recent use of alcohol (75.8%), marijuana (70.1%) and tobacco (69.9%). Relative to other classes, reported use of crack (39.1%), heroin (19.9%), codeine (15.8%) and oxycodone (13.9%) was elevated. Use of alcohol and hallucinogens was less common compared with other substance using classes. Compared with men in the limited drug use class, multivariable results suggested that men in this class had higher escape motivation (aOR = 1.09, 95%CI = [1.05, 1.15]); were more likely to be non-gay identified (aOR = 3.16, 95%CI = [1.63, 6.10]) and to be out of work (vs. being employed in a professional-class occupation; aOR = 0.30, 95%CI = [0.15, 0.61]; vs. working class occupation; aOR = 0.42, 95%CI = [0.22, 0.81]); and were less likely to be stably housed (aOR = 0.29, 95%CI = [0.14, 0.59]).

Class 6: Assorted Drug Use

Class 6, representing 4.5% of respondents, was characterised by recent use of all commonly reported drugs. Compared with men in the limited drug use class, multivariable results suggested that men in this class were younger (aOR = 0.95, 95%CI = [0.91, 0.99]); had higher sexual sensation seeking (aOR = 1.13, 95%CI = [1.02, 1.26]) and escape motivation (aOR = 1.07, 95%CI = [1.00, 1.14]); were more likely to be non-gay identified (aOR = 2.97, 95%CI = [1.14, 7.72]), to be HIV-positive (aOR = 5.97, 95%CI = [2.18, 16.34]), to receive income from drug sales (aOR = 19.77, 95%CI = [3.65, 106.89]) and to attend group sex events in the P6M (aOR = 3.26, 95%CI = [1.39, 7.63]); and were less likely to be stably housed (aOR = 0.23, 95%CI = [0.08, 0.63]).

Discussion

While the plurality of men were classified as engaging in limited drug use (36.7%), five additional substance use classes were identified, including: conventional drug use (25.9%), street drug use (12.1%), sex-drug use (11.4%), club drug use (9.5%) and assorted drug use (4.5%). Conventional drug use was characterised by consumption of a number of frequently reported substances such as alcohol (reported by 85.9% of sample), marijuana (reported by 61.1% of sample), tobacco (reported by 43.8% of sample), ecstasy (reported by 25.5% of sample), poppers (reported by 37.6% of sample) and cocaine (reported by 25.8% of sample). The next most prevalent class, street drug use, was characterised by much less frequent alcohol use compared to other classes (matching the probability of limited drug use class) as well as lower probability of using so called “party drugs” (e.g., ecstasy, mushrooms, LSD). These may be reflective of the prohibitive costs of bars and clubs for these individuals, especially given their lower socioeconomic standing. Similarly, men in this class had higher probability of reporting highly addictive “street drugs” (e.g., heroin, codeine, oxycodone, crack) compared to men in the other classes (except, of course, the assorted drug use class) – potentially suggesting greater social marginalisation. Next, the sex drug class had a high proportion of men reporting so called “Sex/PnP/chemsex” drugs (e.g., GHB, poppers, erectile dysfunction drugs, crystal methamphetamine). Conversely, men in the closely related club drug use class were unlikely to report crystal methamphetamine and erectile dysfunction drugs and instead had high probabilities of reporting so called party/circuit/club drugs (e.g., LSD, mushrooms, ecstasy, cocaine). The subtle distinction between these classes highlights how individuals may differentially integrate substance use into their sex lives. Finally, the assorted drug use class was characterised by elevated use of most drugs – even compared to other polysubstance users. Indeed, these individuals seem to access drugs from a variety of categories that surpass the patterns exhibited by individuals in other classes. For instance, while men in the assorted drug use class exhibited a number of characteristics in common with those in the street drug use class (e.g., high unemployment, high homelessness, use of highly addictive substances), they seemed to combine these with sex and party drugs in a way that indicates greater socialised and sexualised substance use. It is also worth noting that the assorted drug use class exhibited the highest levels of injection drug use (47.1%), even compared to men in the sex drug use (26.1%) and street drug use (23.5%) classes – despite all three groups reporting use of injectable drugs. This likely reflects their increased and concurrent use of multiple, commonly injected drugs (e.g., crystal methamphetamine, cocaine and heroine) compared to other groups in which these drugs are either less likely to be used or are not used concurrently with other injectable drugs.

Comparison with Previous LCA Studies

Comparing our latent class structure with other findings, three previous studies have identified three-class LCA solutions among subgroups of Malaysian, African American and young American gay and bisexual men (Lim et al. 2015; Newcomb et al. 2014; Tobin et al. 2015); in a general sample of Chicagoan gay and bisexual men, McCarty-Caplan and colleagues identified a four-class solution (McCarty-Caplan, Jantz, and Swartz 2014). In this latter study, classes were characterised by low (i.e., limited) drug use (64%), moderate drug use (22%), assorted drug use (3%) and sex drug use (10%) – classes analogous to four of the six drug use classes identified here. Differences in class structure likely arise from their use of weekly measures of alcohol and cannabis use and by pre-collapsing some drugs into theoretically related categories (e.g., club drugs) rather than allowing indicator response probabilities to load into the LCA for specific drugs (e.g., ecstasy, mushrooms, LSD). In another study, Yu and colleagues used similar indicators to those used in the present study and arrived at a six-class LCA solution, which consisted of low/no drug use (43.6%), recreational drug use (29.1%), poppers with prescription erectile drugs (7.8%), poppers with non-prescription erectile drugs (1.5%), moderate poly-drug use (12.5%) and high poly-drug use (5.5%). While these classes are comparable with those in the present study, several differences are clear. First, as we did not delineate between prescription and non-prescription erectile dysfunction drug use, our LCA model could not replicate these results. Second, Yu et al. did not identify a distinct “club drug use” class, which is likely related to differences in sampling methodologies (i.e., national online convenience sampling [n = 8,717]; vs. metropolitan RDS in the current study [n = 774]). This is especially important to consider because the phenomena of “club drug use” may differ widely based on specific regional contexts and indeed post hoc definitions of class behaviour, regardless of how well they are informed by cultural knowledge, are subject to bias. Regardless of these differences, the results of our study reinforce the utility of using LCA to examine substance use patterns among gay and bisexual men. Furthermore, they suggest that future studies may be able to use latent classes of substance use as more holistic descriptors of gay and bisexual men’s substance use. Such distal outcome analysis can be conducted by including these as variables as explanatory factors for other outcomes important to gay and bisexual men’s health.

Theoretical Interpretations

Selecting candidate variables based on Bourdieu’s field theory, we found that, in addition to regularly identified psychological motivators for substance use (i.e., sexual sensation seeking and cognitive escape), social (i.e., age, HIV-status, non-gay identity, patronage of gay bars and participation in group sex events) and economic (i.e., annual income, income from drug sales, housing stability and occupation) indicators were selected as key covariates of class membership. The present bivariable and multivariable results thereby provide quantitative support for the proposed differences in class demographics, economic status and social behaviour – highlighting substance use as a key marker of social identity and position (Amaro 2016; O’Byrne and Holmes 2011). For instance, men in the assorted drug use, sex drug use and club drug use classes were more likely to receive income from non-work-related sources, such as drug sales – indicating increased economic marginalisation. Further, men belonging to the street drug and sex drug use classes were more likely to be out of work and less likely to have professional-class occupations. This supports Bourdieu’s observation that socioeconomic status acts as a primary boundary of social division. Indeed, for Bourdieu, individuals “are both classified and classifiers…[whom] classify according to (or depending upon) their position within classifications” (Bourdieu 1987, 2). This interpretation of substance use patterns – as subordinate to the macro-socioeconomic and cultural pressures on individuals – underscores the deficiency of neoliberal behavioural psychologies.

We also found that identity-related factors and patterns of social and community connectedness were also salient covariates of class membership. For instance, club drug use and conventional drug use were associated with patronage of gay bars and clubs and assorted drug use and sex-drug use were associated with participation in group sex events. Together, these associations highlight the ongoing role that gay venues and events play in shaping substance use behaviour and social bonding among gay men – a finding regularly originating from qualitative work (Amaro 2016; McKay et al. 2012; O’Byrne and Holmes 2011; Weatherburn et al. 2017). Relatedly, we observed that the club drug and conventional drug use classes did not have significantly higher cognitive escape – suggesting that the motivators underlying substance use in these classes is driven primarily by social factors. Furthermore, we note that personal preferences and sexual ambitions also play an important role in shaping these scenes and networks (Weatherburn et al. 2017). For example, we observed that sensation seeking was associated with assorted drug use, club drug use and sex drug use; and that bisexual/other identity was associated with assorted drug use and street drug use.

Of course, if Bourdieu’s fields were truly as deterministic as they are sometimes conceptualised, we would expect the delineation between substance use patterns to be crisper than those observed. Indeed, while a number of key social, economic and identity-related factors were shown to promote particular proclivities of substance use, the observed latent classes were comprised of diverse individuals that – despite being distinct in the aggregate – represented a broad spectrum of nearly all characteristics. While, Bourdieu argues that the hierarchical construction of social fields allows for this sort of nuance (Bourdieu 1987, 1993), recent research on gay and bisexual men’s substance use also highlights how so called “littoral spaces” allow for behaviour that is divergent from an individual’s “everyday experience” (Melendez-Torres and Bonell 2017; Pollard, Nadarzynski and Llewellyn 2017). In other words, some individuals – likely those with sufficient cultural, social and economic capital – can cross over, navigate and perform in a multiplicity of cultural fields or spaces. Based on our findings, it is likely the combination of social coping and littoral performances that shapes patterns of substance use among gay and bisexual men.

Limitations

Readers should consider several limitations. First, LCA is sensitive to the omission and inclusion of LCA indicators (i.e., individual drugs used in the current study). While several indicator selection strategies have been proposed (Dean and Raftery 2010; Fop, Smart and Murphy 2015), none have been widely adopted for use. Second, LCA may be sensitive to the number of indicators used. Applied LCA studies suggest that including a greater number of indicators is generally beneficial, particularly when sample sizes are sub-optimal (Morovati 2014; Wurpts and Geiser 2014). Third, due to power constraints, LCA studies may misestimate the number of latent classes. While various power requirements have been proposed for LCA — including n=250 (Tein, Coxe and Cham 2013), n=500 (Finch and Bronk 2011) and n=1,000 (Morovati 2014) — objective standards such as these have proven difficult to confirm as they depend on a variety of context-specific factors (e.g., the ‘true’ number of latent classes, the relative size of classes, sample size, number of indicators; Dziak and Donna, 2012; Nylund, Asparouhov and Muthen, 2007). Similarly, power restrictions due to small counts in latent classes limited our ability to build explanatory models accounting for the full spectrum of behaviour associated with class membership. Fourth, as shown in Supplemental Table 1 (online), we note the relatively poor separability of the “conventional drug” and “street drug” use classes. As the entropy for the six-class model was <0.80 (i.e., 0.76), the relatively low posterior probabilities of these classes are suggestive of potential misclassification error between them. With that said, low entropy scores are likely attributable to the quality of indicators which do not significantly vary across specific patterns of substance use (e.g., alcohol, tobacco and marijuana are common in most classes while other drugs are not common in any of the classes – thus providing low distinguishability). However, the inclusion of these indicators remains important given their theoretical importance in the substance use literature. To overcome this limitation, we note that proportional assignment was used. However, this class assignment method may overestimate the standard errors and thus underestimate the strength of association for key variables (Bakk, Oberski and Vermunt 2014). Yet, as we have conducted multiple tests, the larger standard errors are actually favourable given the increased likelihood of family wise error. Fifth, as PROC LCA does not allow for RDS-adjustment, RDS weights were not used in the present study. It is possible, therefore, that class composition is misestimated and that our data our not representative beyond a population accessible through traditional chain-referral sampling. Finally, as our data are cross sectional and characterise patterns of substance use at a single time point, future longitudinal analyses are needed to understand the longitudinal stability of substance use behaviour.

Conclusion

Our findings expand on previous LCA studies, which show that patterns of substance use relate to key risk factors for HIV by highlighting the social, economic and identity-related factors that underlie patterns of substance use among gay and bisexual men. These findings underscore the need for substance use policies, primary prevention efforts and treatment programs that address minority stress with attention to the diversity of gay and bisexual men’s experiences. Further, we argue that this need stands in stark contrast to policies and programmes which further inculcate class divisions by criminalising and stigmatising substance users. Instead, public health programs should aim to reduce social disparities between mainstream and marginalised groups of gay and bisexual men, such as those with lower socioeconomic status and those who do not identify as gay.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Momentum Study respondents, office staff and community advisory board, as well as our community partner agencies, Health Initiative for Men, YouthCo HIV and Hep C Society and Positive Living Society of BC.

Funding

Momentum is funded through the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA031055–01A1) and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MOP-107544, PJT-15139). Dr. Lachowsky was supported by a CANFAR/CTN Postdoctoral Fellowship Award. Drs. Moore and Lachowsky are supported by a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (#5209, #16863). Dr. Armstrong is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant # MFE-152443).

References

- Ahmed Alysha-Karima, Weatherburn Peter, Reid David, Hickson Ford, Sergio Torres-Rueda Paul Steinberg, and Bourne Adam. 2016. “Social Norms Related to Combining Drugs and Sex (‘chemsex’) among Gay Men in South London.” The International Journal on Drug Policy 38 (December): 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro Romain. 2016. “Taking Chances for Love? Reflections on Love, Risk, and Harm Reduction in a Gay Slamming Subculture.” Contemporary Drug Problems 43 (3): 216–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450916658295. [Google Scholar]

- Bakk Zsuzsa, Oberski Daniel L., and Vermunt Jeroen K.. 2014. “Relating Latent Class Assignments to External Variables: Standard Errors for Correct Inference.” Political Analysis 22 (04): 520–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé Allan. 2003. “The History of Gay Bathhouses.” Journal of Homosexuality 44 (3–4): 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v44n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu Pierre. 1986. “The Force of Law: Toward a Sociology of the Juridical Field.” Hastings Law Journal 38: 805. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu Pierre. 1987. “What Makes a Social Class? On the Theoretical and Practical Existence Of Groups.” Berkeley Journal of Sociology 32: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois Philippe. 2003. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano Richard M., Kelly Brian C., Easterbrook Adam, and Parsons Jeffrey T.. 2011. “Community and Drug Use among Gay Men: The Role of Neighborhoods and Networks.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 52 (1): 74–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean Nema, and Raftery Adrian E.. 2010. “Latent Class Analysis Variable Selection.” Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics 62 (1): 11–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10463-009-0258-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias José G., and Vermunt Jeroen K.. 2008. “A Bootstrap-Based Aggregate Classifier for Model-Based Clustering.” Computational Statistics 23 (4): 643–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-007-0103-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dziak JJ, and Donna LC. 2012. “Sensitivity and Specificity of Information Criteria.” Technical Report #12–119 Technical Report Series. Pennsylvania: The Methodology Center, The Pennsylvania State University; https://methodology.psu.edu/media/techreports/12-119.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, Holmes W, and Cotton Bronk Kendall. 2011. “Conducting Confirmatory Latent Class Analysis Using Mplus.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 18 (1): 132–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2011.532732. [Google Scholar]

- Fop Michael, Smart Keith, and Brendan Murphy Thomas. 2015. “Variable Selection for Latent Class Analysis with Application to Low Back Pain Diagnosis.” ArXiv:1512.03350 [Stat], December http://arxiv.org/abs/1512.03350. [Google Scholar]

- Frost David M., and Meyer Ilan H.. 2012. “Measuring Community Connectedness among Diverse Sexual Minority Populations.” Journal of Sex Research 49 (1): 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.565427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn Douglas. 1997. “Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations*.” Society for the Study of Social Problems 44 (2): 174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Herek Gregory M., and Greene Beverly. 1995. AIDS, Identity, and Community: The HIV Epidemic and Lesbians and Gay Men. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Israelstam Stephen, and Lambert Sylvia. 1984. “Gay Bars.” Journal of Drug Issues 14 (4): 637–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204268401400404. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, and Rompa D. 1995. “Sexual Sensation Seeking and Sexual Compulsivity Scales: Reliability, Validity, and Predicting HIV Risk Behavior.” Journal of Personality Assessment 65 (3): 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachowsky Nathan J., Lal Allan, Forrest Jamie I., Kiffer George Card Zishan Cui, Sereda Paul, Rich Ashleigh, et al. 2016. “Including Online-Recruited Seeds: A Respondent-Driven Sample of Men Who Have Sex with Men.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 18 (3): e51 https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Sin How, Cheung Doug H., Guadamuz Thomas E., Wei Chongyi, Koe Stuart, and Altice Frederick L.. 2015. “Latent Class Analysis of Substance Use among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Malaysia: Findings from the Asian Internet MSM Sex Survey.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 151 (June): 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Ting Hsiang, and Mitchell Dayton C. 1997. “Model Selection Information Criteria for Non-Nested Latent Class Models.” Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 22 (3): 249–64. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986022003249. [Google Scholar]

- Lubben James, Blozik Eva, Gillmann Gerhard, Iliffe Steve,Renteln Krus Wolfgang von, Beck John C., and Stuck Andreas E.. 2006. “Performance of an Abbreviated Version of the Lubben Social Network Scale Among Three European Community-Dwelling Older Adult Populations.” The Gerontologist 46 (4): 503–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/46.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty-Caplan David, Jantz Ian, and Swartz James. 2014. “MSM and Drug Use: A Latent Class Analysis of Drug Use and Related Sexual Risk Behaviors.” AIDS and Behavior 18 (7): 1339–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0622-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay Tara, Bryce McDavitt Sheba George, and Mutchler Matt G.. 2012. “‘Their Type of Drugs: Perceptions of Substance Use, Sex, and Social Boundaries among Young African American and Latino Gay and Bisexual Men.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 14 (10): 1183–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.720033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, Vanable PA, Ostrow DG, and Hope B. 2001. “Expectancies of Sexual ‘Escape’ and Sexual Risk among Drug and Alcohol-Involved Gay and Bisexual Men.” Journal of Substance Abuse 13 (1–2): 137–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez-Torres GJ, and Bonell Chris. 2017. “Littoral Spaces of Performance: Findings from a Systematic Review and Re-Analysis of Qualitative Studies on Men Who Have Sex with Men, Substance Use and Social Venues.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 14 (3): 259–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-016-0247-8. [Google Scholar]

- Moore David M., Cui Zishan, Lachowsky Nathan J., Raymond Henry F., Roth Eric, Rich Ashleigh, Sereda Paul, et al. 2016. “HIV Community Viral Load and Factors Associated with Elevated Viremia Among a Community-Based Sample of Men Who Have Sex With Men in Vancouver, Canada:” JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 72 (1): 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morovati Diane. 2014. “The Intersection of Sample Size, Number of Indicators, and Class Enumeration in LCA: A Monte Carlo Study - Alexandria Digital Research Library | Alexandria Digital Research Library.” Santa Barbara: UCSB. https://www.alexandria.ucsb.edu/lib/ark:/48907/f3fj2dx5. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb Michael E., Ryan Daniel T., Greene George J., Garofalo Robert, and Mustanski Brian. 2014. “Prevalence and Patterns of Smoking, Alcohol Use, and Illicit Drug Use in Young Men Who Have Sex with Men.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 141 (August): 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund Karen L., Asparouhov Tihomir, and Muthén Bengt O.. 2007. “Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14 (4): 535–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396. [Google Scholar]

- O’Byrne Patrick, and Holmes Dave. 2011. “Drug Use as Boundary Play: A Qualitative Exploration of Gay Circuit Parties.” Substance Use & Misuse 46 (12): 1510–22. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2011.572329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard Alex, Nadarzynski Tom, and Llewellyn Carrie. 2017. “Syndemics of Stigma, Minority-Stress, Maladaptive Coping, Risk Environments and Littoral Spaces among Men Who Have Sex with Men Using Chemsex.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 0 (0): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1350751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power Jennifer, Mikolajczak Gosia, Bourne Adam, Leonard William, Lyons Anthony, Dowsett Gary, and Lucke Jayne. 2018. “Sex, Drugs and Social Connectedness: Wellbeing among HIV-Positive Gay and Bisexual Men Who Use Party-and-Play Drugs.” Sexual Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room Robin. 2005. “Stigma, Social Inequality and Alcohol and Drug Use.” Drug and Alcohol Review 24 (2): 143–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230500102434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandroni Paola. 2001. “Aphrodisiacs Past and Present: A Historical Review.” Clinical Autonomic Research 11 (5): 303–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02332975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, and Grant M. 1993. “Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II.” Addiction (Abingdon, England) 88 (6): 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith R Philip. 2003. “The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 1 (August): 29 https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tein Jenn-Yun, Coxe Stefany, and Cham Heining. 2013. “Statistical Power to Detect the Correct Number of Classes in Latent Profile Analysis.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 20 (4): 640–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2013.824781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin Karin E., Yang Cui, King Kelly, Latkin Carl A., and Curriero Frank C.. 2015. “Associations Between Drug and Alcohol Use Patterns and Sexual Risk in a Sample of African American Men Who Have Sex with Men.” AIDS and Behavior 20 (3): 590–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1214-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherburn P, Hickson F, Reid D, Torres-Rueda S, and Bourne A. 2017. “Motivations and Values Associated with Combining Sex and Illicit Drugs (‘chemsex’) among Gay Men in South London: Findings from a Qualitative Study.” Sexually Transmitted Infections 93 (3): 203–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2016-052695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurpts Ingrid C., and Geiser Christian. 2014. “Is Adding More Indicators to a Latent Class Analysis Beneficial or Detrimental? Results of a Monte-Carlo Study.” Frontiers in Psychology 5 (August): 920 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Chih-Chien, and Yang Chih-Chiang. 2007. “Separating Latent Classes by Information Criteria.” Journal of Classification 24 (2): 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00357-007-0010-1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.