Abstract

Women acquire HIV mainly through sexual intercourse. However, low transmission rates per sexual act indicate that local immune mechanisms contribute to HIV prevention. Neutrophils represent 10-20% of the genital immune cells in healthy women. Neutrophils mediate mucosal protection against bacterial and fungal pathogens through different mechanisms, including the release of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs). NETs are DNA fragments associated with antimicrobial granular proteins. Despite neutrophil abundance and central contributions to innate immunity in the genital tract, their role in protection against HIV-acquisition is unknown. We found that stimulation of human genital neutrophils with HIV viral-like particles (HIV-VLP) induced NET release within minutes of viral exposure, through ROS-independent mechanisms that resulted in immediate entrapment of HIV-VLPs. Incubation of infectious HIV with pre-formed genital NETs prevented infection of susceptible cells through irreversible viral inactivation. HIV inactivation by NETs from genital neutrophils could represent a previously unrecognized form of mucosal protection against HIV-acquisition.

Keywords: HIV, HIV-acquisition, HIV-prevention, neutrophils, genital neutrophils, neutrophil extracellular traps, NETosis, female genital tract, mucosa, women, reactive oxygen species, TLR, endometrium, endocervix, ectocervix

INTRODUCTION

Neutrophils are innate immune cells known to provide mucosal protection against bacterial and fungal pathogens1. As the first leukocytes recruited to sites of acute infection and inflammation, neutrophils display a broad range of functions, including direct pathogen-killing, release of inflammatory mediators, immune cell recruitment and tissue remodeling2,3.

Neutrophils inactivate pathogens through multiple mechanisms, including phagocytosis, degranulation and NETosis1. NETosis is characterized by the extrusion of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs), consisting of DNA fragments associated with granular proteins with antimicrobial activity4. NETs are released through an active process to inactivate a wide range of bacterial and fungal pathogens in vitro and in vivo4-7. While aberrant chronic NETosis and acute NETosis induced under sterile conditions are thought to contribute to pathology3,8,9, acute vital NETosis against infectious agents has been proposed as an efficient defense mechanism that prevents collateral tissue damage by concentrating antimicrobials and reducing protease toxicity6,10-12.

Recently, blood neutrophils were reported to release NETs and inactivate HIV in vitro13, providing evidence that neutrophils have the ability to recognize and inactivate HIV. However, the role of NETosis in protection against HIV infection at mucosal sites remains a gap in our knowledge. In the context of HIV prevention, location is key14, since NET inactivation of HIV in the genital mucosa has the potential of preventing HIV acquisition.

Genital neutrophils are present throughout the female genital tract15, and are phenotypically and functionally different than those found in blood16. Neutrophils are present within the stratified epithelium of the vagina17 and on the mucosal surfaces of the genital tract, where they can be recovered by cervico-vaginal lavage or cytobrush18. Neutrophils are also abundant in the endometrium, where they play a critical role in tissue remodeling during menstruation19. Further, because of their first-responder nature, neutrophils are rapidly recruited to sites of injury20, and potential viral entry.

Supporting clinical evidence for a role of neutrophils in preventing HIV transmission comes from clinical studies analyzing the association between low neutrophil counts, a frequent condition in Africa, and HIV acquisition risk19,20. Kourtis et al demonstrated increased intrauterine perinatal transmission of HIV in mothers with lower neutrophil counts, while Ransuram et al reported increased risk of HIV acquisition in female sexual workers with neutropenia and high platelet counts21,22. In contrast, studies performed in the context of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and inflammation, both generally associated with neutrophil recruitment, report associations between increased risk of HIV acquisition and the presence of neutrophil-derived molecules in cervico-vaginal secretions23-25. These apparently contradictory findings highlight the gap in our knowledge about neutrophil mucosal responses to HIV and the need to determine the role of NETosis in HIV acquisition.

Due to their location, both in the stroma beneath the epithelial layer and on mucosal surfaces17,18, it is likely that neutrophils are among the first cells to encounter HIV after genital viral exposure. Despite their abundance throughout the human genital tract15, their distinct characteristics when compared to blood neutrophils16, and crucial contribution to innate immunity at mucosal surfaces, the direct role of genital neutrophils in HIV protection remains a gap in our knowledge.

RESULTS

Genital neutrophils entrap HIV in NETs

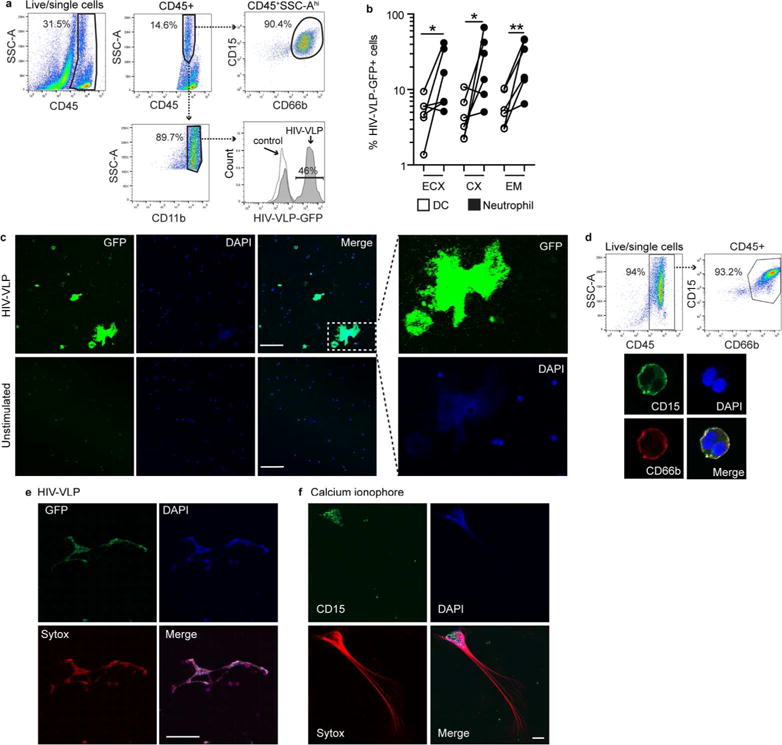

We recently demonstrated that genital dendritic cells (DCs) expressing CD11b and CD14 had specific HIV-capture potential26. While investigating HIV-capture in genital mixed cell suspensions, we observed that neutrophils also rapidly captured HIV-VLPs (Fig. 1a), with 3-4 fold more efficacy than DCs (Fig. 1b). Enhanced HIV capture by neutrophils from the ECX and CX was observed in five out of six patients, and from the EM in all patients studied (Fig. 1b). Unexpectedly, fluorescence microscopy analysis revealed high concentration of HIV-VLPs in extracellular DNA structures (Fig. 1c). Since one previous report demonstrated that NETs from blood neutrophils capture HIV13, we investigated if genital neutrophils could release NETs in response to HIV. Purified genital neutrophils (Fig. 1d) were stimulated with HIV-VLPs or with calcium ionophore, a known inducer of NETs27, as a positive control. NETs were detected after HIV-VLP (Fig. 1e), or calcium ionophore (Fig. 1f) stimulation, demonstrating that neutrophils from the genital tract have the ability to release NETs.

Figure 1. Genital neutrophils entrap HIV in NETs.

(a) Representative example of the gating strategy to identify neutrophils after stimulation with HIV-VLP-GFP. Neutrophils were identified as CD45+, SSC-Ahi, CD11bhi. Parallel unstimulated controls showed that this population was also CD15+CD66b+. (b) Comparison of HIV-VLP capture by neutrophils (black dots) or CD14+ dendritic cells (DCs; white dots) in the same tissues from the ECX, CX and EM from 6 different women; matching ECX, CX and EM were obtained from each patient. U Mann-Whitney. *p<0.05; **p<0.01. (c) Representative image of HIV-VLP accumulation (GFP, green) in extracellular DNA structures (DAPI) 1h after stimulation of mixed cell suspensions with HIV-VLP. Bottom row shows unstimulated controls. Scale bar = 200 μm (d) Representative example of purity following magnetic bead selection of genital neutrophils. Purified neutrophils show characteristic nuclear morphology and surface expression of CD15 and CD66b by confocal microscopy. (e) Representative image of the formation of NETs (stained with the nucleic acid dye Sytox) following stimulation with HIV-VLP (GFP, green) (scale bar = 20 μm) or (f) calcium ionophore, using confocal microscopy (scale bar = 5 μm).

Genital neutrophils actively release NETs within minutes after HIV exposure

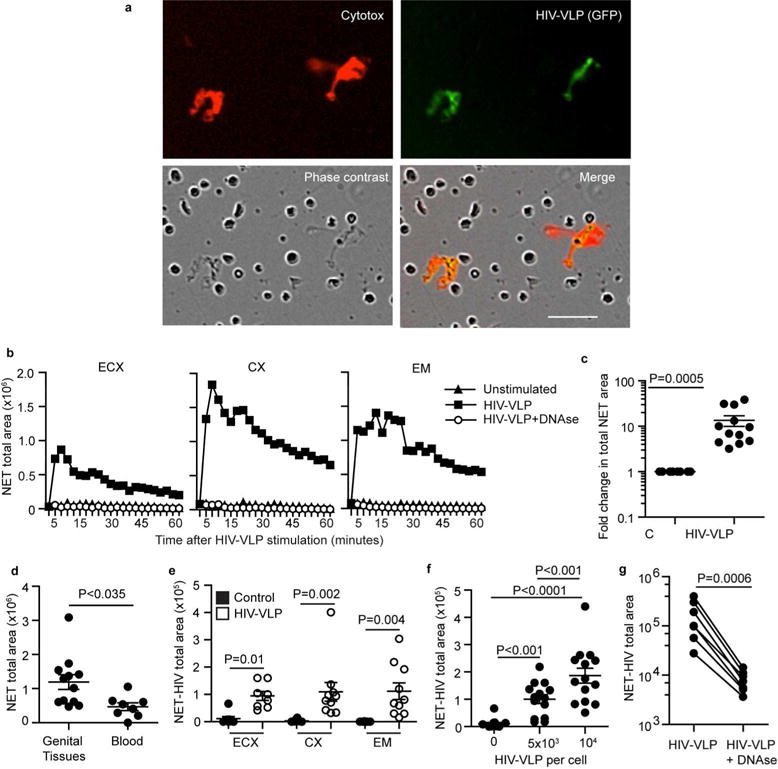

To characterize the dynamics of HIV entrapment by NETs, we optimized a system to visualize NETosis in real time using time-lapse imaging. Mixed cell suspensions from ectocervix, endocervix and endometrium were cultured in media containing cell impermeant DNA-dye (red) and stimulated with GFP-tagged HIV-VLPs (green). When DNA is released into the extracellular compartment, red signal is visualized. Conversely, HIV-VLPs can be detected as green signal. As seen in Fig. 2a, using this system, we detected neutrophil release of DNA (NETs; red) into the extracellular compartment and HIV-VLP entrapment (green). NET release and HIV-VLP capture occurred within minutes of viral stimulation, and continued for approximately 30 min, but new NETosis and HIV-VLP capture was infrequent after that (Fig. 2b and Supplementary videos 1 and 2). As a control, the addition of DNAse in combination with HIV-VLP to the culture media, abolished the formation of NETs (Fig. 2b, white circles; and supplementary video 3). Analysis of NET area in different patients demonstrated a significant increase in extracellular DNA release in the presence of HIV-VLPs (Fig. 2c). Importantly, comparison of neutrophils from blood and genital tissues demonstrated increased NET release by genital neutrophils following HIV stimulation (Fig. 2d). This difference remained significant after excluding from the analysis one outlier data point in the tissue data set (p<0.045). This suggests that mucosal specific factors influence NETosis capacity of neutrophils, and represents further evidence that genital neutrophils are distinct from blood16.

Figure 2. Genital neutrophils actively release NETs within minutes after HIV exposure.

(a) Representative image of NET formation and co-localization with HIV-VLP as visualized using the IncuCyte Zoom system. (b) Representative example of quantification of NET release over time in mixed cell suspensions from ECX, CX and EM from the same woman. Total NET area is represented and reaches maximum magnitude between 15 and 30 min after stimulation. Curves from unstimulated controls (triangles) and DNAse + HIV-VLP treated samples (white circles) overlap at the bottom. (c) Fold change in NET area in HIV-VLP stimulated samples respect to unstimulated controls. Maximal NET area within the first hour is represented for each individual. Each dot represents a different women, and include unmatched samples from ECX, CX and EM. Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. (d) Total NET area after stimulation of genital neutrophils or blood neutrophils with HIV-VLPs. Shown are the mean values of every time point within the first 30 min after subtracting the background signal from unstimulated controls. Each dot represents a different individual. U-Mann Whitney test. (e) Total NET-HIV area in matched samples from ECX, CX and EM. The mean value of all the time points within the first 30 min are shown for HIV-stimulated samples (HIV-VLP) and unstimulated controls. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test; n=10. (f) Dose response studies with increased levels of HIV-VLP per cell. Each dot represents a different tissue, including unmatched ECX, CX and EM. Kruskall-Wallis with Dunns post-test; n=14. (g) DNAse treatment in addition to HIV-VLP diminished NET-HIV complex area. Each dot represents a different tissue, including unmatched ECX, CX and EM. U-Mann Whitney test; n=7.

To quantify HIV capture, coincident red (NET) and green (HIV-VLP) signals were measured. NET-HIV complexes were detected in all genital sites, with no differences between ECX, CX and EM (Fig. 2e). HIV capture was dose-dependent, with increased number of HIV-VLP per cell resulting in greater induction of NET-HIV complexes (Fig. 2f). Furthermore, DNAse treatment significantly reduced viral capture (Fig. 2g), demonstrating that HIV-VLP entrapment is mediated by DNA.

Overall these data demonstrate that HIV stimulates genital neutrophils to release NETs in a time and dose-dependent manner, to entrap and immobilize HIV at different sites in the genital tract.

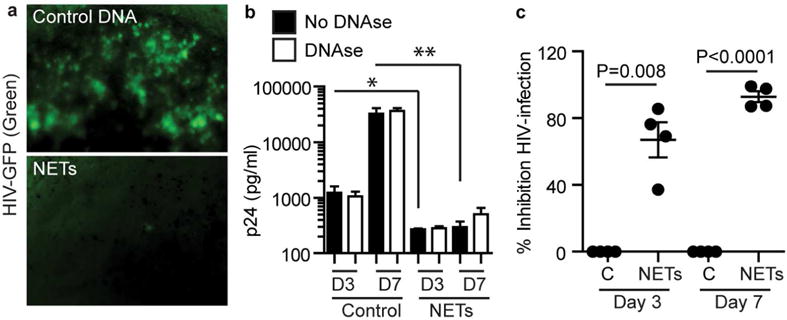

NETs from genital neutrophils inactivate HIV and prevent infection of CD4+ T cells

Next we investigated if HIV entrapment in NETs would result in viral inactivation. To do this, we generated NETs by stimulation of purified genital neutrophils with calcium ionophore, and isolated NETs by centrifugation28. As a control for background extracellular DNA not generated through NETosis, unstimulated neutrophils were incubated with DMSO and centrifuged in the same way as calcium ionophore-stimulated neutrophils. Isolated NETs or DNA control were then incubated with HIV for 1h, prior to the addition of activated CD4+ T cells to measure infection as described in methods. As shown in Fig. 3a, using fluorescent microscopy to detect HIV-infected GFP+ cells 7 days after infection, HIV-infected T cells were abundant in the control condition (green), but undetectable when NETs from ionophore-stimulated neutrophils were present. Additionally, NET inhibition of productive HIV infection was confirmed by measuring released p24 by ELISA 3 and 7 days after infection (Fig. 3b). Productive HIV-infection was observed in the control condition, but absent when NETs were present (Ionophore stimulation). To investigate whether reduced infection was a result of viral inactivation or immobilization by NETs, DNAse was added to HIV-NET complexes to degrade the NETs and release potentially infectious virions. As shown in Fig. 3b (white bars), DNAse treatment to release trapped virus did not increase HIV infection. Quantification of viral suppression in different individuals in the presence of NETs demonstrated almost complete inhibition after 7 days (Fig. 3c). These findings indicate that HIV is irreversibly inactivated by NET contact. Overall, these results demonstrate that NETs from genital neutrophils inactivate HIV and prevent infection of target cells.

Figure 3. NETs from genital neutrophils inactivate HIV and prevent infection of CD4+ T cells.

(a) Representative microscopy image of HIV infected CD4+ T cells (GFP+) 7 days after infection, in the control condition with no NETs present (control DNA) and when purified isolated NETs were present. (b) Levels of p24 as determined by ELISA in the culture supernatants 3 days (D3) and 7 days (D7) after infection, in the absence (control) or presence of pre-formed NETs. Experiments were performed in the absence of DNAse (black bars) or presence of DNAse (white bars) after incubation of NETs with HIV to degrade NETs and release any potentially infectious virions. Bars show one representative example run in triplicates. (c) Percent of inhibition of HIV infection in the NET condition relative to the control condition. 100% inhibition means absence of detectable infection. Each dot represents a different patient source for NETs. One sample t test; n=4.

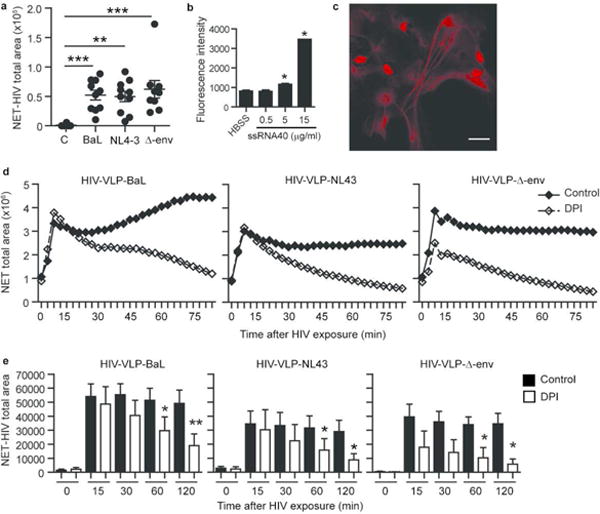

Different HIV strains, HIV lacking envelope and TLR7/8 ligands induce NETosis of genital neutrophils

To gain insight into the mechanisms by which HIV induces NETosis of genital neutrophils, mixed cell suspensions were stimulated with HIV-VLPs with different envelope glycoproteins (BaL and NL4-3) or lack thereof (delta-Env). The three types of HIV-VLPs induced NETosis and the formation of NET-HIV complexes (Fig. 4a), suggesting that the envelope glycoproteins are not required for NETosis induction.

Figure 4. Different HIV strains, HIV lacking envelope and TLR7/8 ligands induce NETosis of genital neutrophils.

(a) NET-HIV complexes were induced after stimulation with HIV-VLP encoding envelope glycoproteins from BaL (R5), NL43 (X4) and lack of envelope (Δ-env). The mean value of the area in the first 30 min is represented. Mixed cell suspensions from each tissue were stimulated with the three different viral constructs; each dot represents a different patient. Kruskall-Wallis with Dunns post-test for multiple comparison correction; n=10. ***p<0.0001; **p<0.01. (b) Dose response studies of the release of DNA after stimulation with ssRNA40, a TLR7/8 ligand. Bars represent fluorescence intensity of Sytox Orange after 1h stimulation. *P<0.05. (c) Representative confocal microscopy image of NET formation after stimulation with ssRNA40 (15 μg/ml) for 1h (scale bar = 20 μm). (d) Time-course curve of the NET total area after stimulation with HIV-VLP BaL, NL43 or Δ-env in the absence (control; black diamonds) or presence of DPI (white diamonds). Lines in the x axis are separated by 3 min intervals. (e) NET-HIV area in the absence (control; black bars) or presence of DPI (white bars). Bars represent the mean value of total NET-HIV area between each indicated time point. Time 0 shows the background before the addition of HIV-VLPs. HIV-VLP BaL=8; NL43=6; Δ-env=4. Mann Whitney test; **p=0.0078; *p<0.05.

Given that HIV-VLPs lacking envelope triggered NETosis, and that TLR stimulation is a common pathway for NETosis induction5,6,13, we investigated whether HIV-derived TLR stimulation would induce NETosis of genital neutrophils. Mixed cell suspensions were stimulated with the TLR7/8 ligand ssRNA40, a single-stranded RNA derived from the HIV-1 long-terminal repeat. Stimulation with ssRNA40 induced DNA release, measured as increased fluorescence intensity, in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 4b). Confocal microscopy of purified genital neutrophils confirmed the induction of NETs after ssRNA40 stimulation (Fig. 4c). This finding is consistent with previous reports demonstrating activation of blood neutrophils by TLR7/8 ligands13,29, and indicates that TLR signaling is a potential pathway for HIV-induced NETosis in genital neutrophils.

NETosis have been described to be mediated through ROS-dependent and -independent pathways30. To investigate if HIV induction of NETs involved ROS-dependent mechanisms, genital neutrophils were incubated with DPI, a known inhibitor of ROS30, prior to HIV stimulation. As shown in Fig. 4d, when neutrophils were stimulated with HIV-VLP containing envelope glycoproteins (BaL or NL43), initial events of NETosis (less than 30 min) were independent of ROS, but were ROS-dependent at latter time points. In contrast, NETosis in response to HIV-VLP lacking envelope was more sensitive to ROS inhibition, with a 50% reduction in the initial magnitude of NETosis. The temporal dynamics of reduction in NETosis correlated with reduced HIV-NET complexes in the DPI-treatment condition after 30 min of stimulation (Fig. 4e). These results demonstrate that the initial triggering of NETosis is ROS-independent and partially driven by the envelope, while ROS-dependent mechanisms are important for the maintenance of the process.

DISCUSSION

Overall our study demonstrates that genital neutrophils recognize HIV and release NETs that inactivate the virus, preventing subsequent infection of HIV-susceptible cells. HIV entrapment and inactivation by NETs is rapid (within minutes) and irreversible, appearing as an efficient mechanism to prevent mucosal HIV acquisition after sexual contact.

While previous data demonstrating HIV-inactivation by NETs from blood neutrophils may be relevant for immunotherapeutic strategies in patients chronically infected with HIV13, our findings are particularly relevant for the prevention of HIV acquisition in the female genital mucosa, and possibly at other mucosal sites in the body. First, we used neutrophils from different anatomical compartments in the female genital tract, which are modified by the tissue environment16, and represent the very cells that will be exposed to HIV after sexual intercourse. Second, we demonstrate that HIV-induction of NETs occurs both with purified genital neutrophils, and in the context of genital mixed cell suspensions, which include tissue resident DCs and other mucosal cells, mimicking the mucosal cell environment. This is in contrast to the findings of Saitoh et al. using blood monocyte-derived dendritic cells, who postulated that NETosis would be counteracted by HIV through actions on dendritic cells and IL-10 induction13. Our results indicate that mucosal NETosis in response to HIV will not be counteracted, given the rapidity of NETosis induction, and our previous observation that genital DCs do not produce IL-10 within the first 3 h after HIV-stimulation26. Third, NETs from genital neutrophils are released within minutes of viral exposure, and infrequent after 30 min, suggesting an acute self-controlled mechanism unlikely to induce tissue damage. Importantly, irreversible inactivation of HIV, as seen in our study, would prevent infection of any susceptible cell that may be attracted to HIV-NET complexes by chemotactic molecules released by neutrophils during their activation.

From a mechanistic standpoint, our findings suggest that HIV induces neutrophil NETosis through at least two different mechanisms. Our results that HIV-VLPs lacking envelope induce NETosis are consistent with TLR7/8 stimulation by viral RNA. Additionally, it is likely that the envelope glycoproteins act through ROS-independent pathways to modulate the initial magnitude of NET release. Whereas our results confirm that late events of HIV-induced NETosis are ROS-dependent13; they add a new dimension by demonstrating that triggering and early events of NETosis in response to HIV are ROS-independent, as reported for other pathogens5,31.

Our demonstration that HIV-inactivation by NETs occurs in vitro, provides a solid foundation to further examine the interactions of neutrophils with other immune cells in the female genital tract both in tissue explants and in vivo animal models. While we postulate that NETosis is an important protective mechanism in healthy women, further studies are needed to define the protective role of NETs against HIV acquisition in the context of sexually transmitted infections, which are known to damage epithelial cells and recruit HIV-target cells to sites of infection. In addition, sexually transmitted pathogens induce neutrophil degranulation and phagocytosis (which may inhibit NETosis pathways32), and display multiple mechanisms to evade neutrophil-mediated immunity, including inhibition of NETs killing (Neisseria gonorrhea)33-36, inactivation of antimicrobials (Chlamydia trachomatis)37,38 and induction of neutrophil apoptosis (Trichomonas vaginalis)39. Future studies are needed to test the hypothesis that interference of sexually transmitted pathogens with NETosis and anti-HIV activity in NETs may represent an unrecognized contributing factor for increased risk of HIV acquisition.

Our studies extend the findings of others that neutrophils, in addition to playing an important bystander role in inflammation23-25, are unrecognized effector cells with the ability to directly inactivate HIV. NETosis of genital neutrophils in response to HIV may represent a constitutive baseline protection mechanism contributing to the low transmission rate per sexual act described in epidemiological studies40. However, recognizing that neutrophils are present under conditions known to increase susceptibility to HIV infection (i.e. genital inflammation, epithelial disruption or genital infections), future studies are needed to determine the multiple factors that may shift the balance from neutrophil-mediated viral inactivation to inflammation and increased risk of HIV acquisition. Given that neutrophils are present in the genital tract under physiological conditions15-17, but can also be rapidly recruited and activated under pathological conditions, it is possible that neutrophils play separate and distinct roles in HIV acquisition under different circumstances.

Our findings challenge the current model of mucosal HIV acquisition, by demonstrating that genital neutrophils, not previously considered to interact with HIV at mucosal surfaces or to play a role in protection, respond within minutes to viral exposure to prevent HIV infection of target cells. Recognizing that the initial interactions between HIV and the immune system in the genital tract have the potential to prevent infection of target cells and HIV acquisition14, our findings may represent a previously unrecognized mechanism of mucosal protection that can aid the development of effective prevention strategies for women.

METHODS

Study subjects

Written informed consent was obtained before surgery from HIV-negative women undergoing hysterectomies at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (Lebanon, NH). Studies were approved by Dartmouth College Institutional Review Board and the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS). Surgery was performed to treat benign conditions including fibroids, prolapse and menorrhagia. Hormonal contraceptives were not administered before surgery. Trained pathologists selected tissue samples from ectocervix (ECX), endocervix (CX), and endometrium (EM), free of pathological lesions and distant from the sites of pathology. Women used in this study were premenopausal, HIV- and HPV- but no additional information regarding other genital infections was available.

Tissue processing

For comparisons between different anatomical sites, matched tissues from the ECX, CX and EM of the same patient were used whenever possible as indicated. In some cases, only endometrial tissue was provided by pathology. Vaginal tissues were not available. Tissues were generally processed within 6h after surgery. In exceptional cases of late surgery, tissues were kept overnight at 4°C and processed in the morning. Tissues were processed to obtain a stromal cell suspension as described previously26,41-43, using 0.05% collagenase type IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 0.01% DNAse (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ). After filtering through a 20μm mesh screen (Small Parts) to separate epithelial cells from stromal cells. Cell preparations underwent dead cell removal (Dead Cell Removal Kit, Miltenyi biotech) as described41, resulting in more than 90% cell viability by trypan blue staining. After dead cell removal, mixed cell suspensions were used for NETosis experiments as indicated, or underwent further processing to purify neutrophils.

Neutrophil purification

Stromal mixed cell suspensions were further purified by standard Ficoll density gradient centrifugation to separate mononuclear cells, which remained above the Ficoll. After red blood cell lysis, genital neutrophils were purified from the pellets by magnetic bead selection with the CD66abce microbead Kit (Miltenyi biotec). Following two rounds of selection, purity of the population was >88% as determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 1d). Characteristic neutrophil morphology was confirmed with confocal microscopy (Fig. 1d).

Neutrophils from blood were isolated with whole blood CD15 microbeads and whole blood column kit following instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of the population was >95%.

Generation of GFP-labeled Virus-like particles

A modified pNL4-3 provirus-based plasmid for expression of GFP-labelled virus like particles (VLP) and encoding NL4-3 Env in cis, (referred to as K795) was described previously44. Briefly, the EGFP coding sequence is expressed in frame at the 3′ end of gag, replacing the protease and most of reverse transcriptase coding region. The Ψ-signal on the RNA and the entire Gag open reading frame remain intact. In addition, a plasmid in which the env orf was inactivated, and from which no functional Env is expressed (referred to as K806) was derived from K795 for pseudotyping, and complemented with pBaL.26 Env expression plasmid (NIH AIDS Reagent program, Catalog Number 11446, contributed by Dr. John Mascola)45. Virus-like particles which are EGFP-labeled and non-infectious were produced by transfection, concentrated by ultracentrifugation and enumerated essentially as described44.

Viral capture assay

As described previously26, mixed cell suspensions were incubated with HIV-GFP viral like particles (VLPs) carrying R5 env proteins at a concentration of 10,000 VLPs/cell for 1h at 37 °C. Following incubation, cells were washed to remove unbound VLPs and stained for flow cytometric analysis. Viral capture is shown as percentage of GFP+ cells in the appropriate DC or neutrophil gates, according to the antibodies described below.

Flow cytometry

Mixed cell suspensions were stained for surface markers with combinations of the following antibodies: CD45-vioblue450, CD11b-PE (Tonbo, San Diego, CA), CD3-VioGreen, CD15-FITC, CD66b-APC (Miltenyi biotec), CD11c-PerCp-Cy5.5, CD1c-PE-dazzle, HLA-DR-BV570, CD3-APC (Biolegend), CD14-e780, (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA). Dead cells were excluded with 7AAD (Southern Biotech) or zombie dye yellow staining (Biolegend). Analysis was performed on 8-color MACSQuant 10 (Miltenyi biotech) or Gallios (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) flow cytometers and data analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc. Ashland, OR). Expression of surface markers is shown as percentage of positive cells. Fluorescence minus one (FMO) strategy was used to establish appropriate gates. Cells were gated as described before26.

NET induction and confocal microscopy

Purified genital neutrophils were re-suspended in HBSS containing Sytox orange nucleic acid stain (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and plated on coverslips. HIV-VLP GFP-labeled (5,000 VLP/cell, unless otherwise specified), calcium ionophore A23187 (Sigma), or ssRNA40 (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) were used to stimulate NETosis for 1h at 37 °C. Unstimulated neutrophils incubated in HBSS with Sytox orange were used as unstimulated controls. Cells were carefully washed with HBSS, and samples were mounted in Pro-Long Diamond anti-fade mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 laser-scanning confocal microscope in combination with Zeiss Zen software.

Time-lapse microscopy of NETs

Mixed cell suspensions or purified neutrophils as indicated were plated in flat-bottom 96-well plates in HBSS containing Incucyte Cytotox red reagent (Essen Bioscience, Ann Arbor, MI), a cell impermeant DNA stain. HIV-VLP GFP-labeled were added to the cells and the plate was imaged using the Incucyte Zoom system (Essen Bioscience) with 10× objective. Images were collected every 2-3 minutes and fluorescent signal quantified with Incucyte Zoom software.

Quantification of NETs and HIV-NET complexes

To quantify NETs, total area of fluorescent red signal (cytotox red) was quantified. A mask was established with size constrictions based on negative controls treated with DNAse to exclude intracellular red signal (potential dead cells, not NETs). To measure HIV capture, NET-HIV complexes were quantified as coincident red (Cytotox red) and green (HIV-VLP GFP) objects. Since 10× magnification was used, single viral particles were undetectable, HIV-VLPs can be visualized only when multiple particles were concentrated in NETs or in cells.

Viruses

The replication-competent GFP-encoding infectious molecular clone (pNLENG1i-BaL.ecto)46 was derived from pNLENG1-ires47 to express heterologous BaL env gene sequences in an isogenic backbone following the strategy previously described48,49. This reporter virus, collectively referred to as Env-IMC-GFP, expresses GFP upon infection of HIV-1 susceptible target cells.

Generation of CD4+ T cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by standard Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. As described before50, CD4+ T cells were purified from PBMC using magnetic negative selection (Miltenyi Biotech), cultured in Xvivo15 supplemented with 10% inactivated human AB serum, and activated in vitro with Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (2.5 μg/ml; Sigma, St Louis, MO) and IL-2 (50 U/ml) (AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: Human rIL-2 from Dr. Maurice Gately, Hoffmann-La Roche Inc)51 for 1 to 3 days prior to HIV-infection. Purity higher than 98% was obtained after CD4+ T cell magnetic isolation.

NET isolation

Isolation of NETs was adapted from28. Genital neutrophils were stimulated with calcium ionophore (Sigma; 25 μM) for 1h27. After incubation, cells and supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min to generate a cell pellet. Supernatants were then transferred to a new tube and centrifuged for 18,000 g for 10 min at 4° C, to generate a DNA pellet containing NETs. DNA content in NET and control conditions was quantified, resuspended in PBS, and plated in round bottom ultra-low attachment 96-well plates (Corning) in triplicates. Plates were kept overnight at 4° C and HIV-inactivation assays performed the next day.

HIV-inactivation assays

NETs and DNA controls were incubated with replication-competent GFP-encoding HIV (MOI=0.5) for 1h. For some experiments, DNAse (Worthington Biochemical) was added after this incubation period for 15 min to degrade NETs and release any potentially infectious virions. CD4+ T cells were then added to the wells, spun down to ensure contact with NETs and incubated for 2 additional hours at 37 °C. After incubation, residual virus was washed away and fresh media added to each well. Cell cultures were maintained for 7 days, with half of the well media collected and replaced with fresh media on day 3. This reporter virus, expresses GFP upon infection of HIV-1 susceptible target cells. GFP expression levels were measured by fluorescence microscopy with the Incucyte Zoom system. Levels of p24 were measured in conditioned media by p24 ELISA (Advanced Bioscience Laboratories, Rockville, MD) on days 3 and 7 after infection.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. A two sided P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Comparison of two groups was performed with the non-parametric U-Mann Whitney test or Wilcoxon paired test. Comparison of three or more groups was performed applying the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s post-test.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary video 1. Genital neutrophils release NETs after stimulation with HIV-VLPs.

Supplementary video 2. Unstimulated control neutrophils. Genital neutrophils plated under the same conditions as those shown in supplementary video 1, but no HIV-VLPs added.

Supplementary video 3. DNAse control. Genital neutrophils stimulated with HIV-VLPs in the presence of DNAse. DNAse prevents the formation of NETs and HIV entrapment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Rossoll and Zheng Shen for technical assistance and Kenneth Ordorff for assistance with confocal microscopy. We are grateful to Dr. John C. Kappes at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for the generous provision of plasmids (K795 and K806) for VLP-GFP production. We thank the study participants, Pathologists, Obstetrics and Gynecology surgeons, operating room nurses and support personnel at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. Flow cytometric analysis was carried out in DartLab, the Immunoassay and Flow Cytometry Shared Resource at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth supported by (P30CA023108-37). Study supported by the Hitchcock Foundation (MR-G), NIH grants AI102838 and AI117739 (CRW), P30 AI27767 Birmingham Center for AIDS Research – Virology Core (CO), and the Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute, under award number UL1TR001086 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS. FDB performed experiments and analyzed data; CO proposed the strategy to use HIV-VLP-GFP and GFP reporter HIV, and produced both VLP and infectious virus stocks; CRW made critical suggestions to the experimental design and data interpretations, and critically edited the manuscript for intellectual content; MR-G conceived and designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed data and interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:159–175. doi: 10.1038/nri3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soehnlein O, Steffens S, Hidalgo A, Weber C. Neutrophils as protagonists and targets in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:248–261. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinkmann V, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilsczek FH, et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2010;185:7413–7425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yipp BG, et al. Infection-induced NETosis is a dynamic process involving neutrophil multitasking in vivo. Nat Med. 2012;18:1386–1393. doi: 10.1038/nm.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urban CF, Reichard U, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps capture and kill Candida albicans yeast and hyphal forms. Cellular microbiology. 2006;8:668–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lande R, et al. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA-peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:73ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skopelja S, et al. The role for neutrophil extracellular traps in cystic fibrosis autoimmunity. JCI insight. 2016;1:e88912. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.88912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohanty T, et al. A novel mechanism for NETosis provides antimicrobial defense at the oral mucosa. Blood. 2015;126:2128–2137. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-641142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tillack K, Breiden P, Martin R, Sospedra M. T lymphocyte priming by neutrophil extracellular traps links innate and adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2012;188:3150–3159. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belorgey D, Bieth JG. DNA binds neutrophil elastase and mucus proteinase inhibitor and impairs their functional activity. FEBS letters. 1995;361:265–268. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saitoh T, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate a host defense response to human immunodeficiency virus-1. Cell host & microbe. 2012;12:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haase AT. Early events in sexual transmission of HIV and SIV and opportunities for interventions. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:127–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-080709-124959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Givan AL, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of leukocytes in the human female reproductive tract: comparison of fallopian tube, uterus, cervix, and vagina. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1997;38:350–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith JM, Wira CR, Fanger MW, Shen L. Human fallopian tube neutrophils–a distinct phenotype from blood neutrophils. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2006;56:218–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2006.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sips M, et al. Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in tissues as a potent mechanism for preventive and therapeutic HIV vaccine strategies. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:1584–1595. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nkwanyana NN, et al. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection and inflammation on the composition and yield of cervical mononuclear cells in the female genital tract. Immunology. 2009;128:e746–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wira CR, Rodriguez-Garcia M, Patel MV. The role of sex hormones in immune protection of the female reproductive tract. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:217–230. doi: 10.1038/nri3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leoni G, Neumann PA, Sumagin R, Denning TL, Nusrat A. Wound repair: role of immune-epithelial interactions. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:959–968. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kourtis AP, Hudgens MG, Kayira D. Neutrophil count in African mothers and newborns and HIV transmission risk. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2260–2262. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1202292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsuran V, et al. Duffy-null-associated low neutrophil counts influence HIV-1 susceptibility in high-risk South African black women. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011;52:1248–1256. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold KB, et al. Increased levels of inflammatory cytokines in the female reproductive tract are associated with altered expression of proteases, mucosal barrier proteins, and an influx of HIV-susceptible target cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:194–205. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levinson P, et al. Levels of innate immune factors in genital fluids: association of alpha defensins and LL-37 with genital infections and increased HIV acquisition. AIDS. 2009;23:309–317. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328321809c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan SR, Liu XP, Liao QP. Human defensins and cytokines in vaginal lavage fluid of women with bacterial vaginosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Garcia M, et al. Dendritic cells from the human female reproductive tract rapidly capture and respond to HIV. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:531–544. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrientos L, et al. An improved strategy to recover large fragments of functional human neutrophil extracellular traps. Frontiers in immunology. 2013;4:166. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Najmeh S, Cools-Lartigue J, Giannias B, Spicer J, Ferri LE. Simplified Human Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) Isolation and Handling. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2015 doi: 10.3791/52687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giraldo DM, Hernandez JC, Urcuqui-Inchima S. HIV-1-derived single-stranded RNA acts as activator of human neutrophils. Immunologic research. 2016;64:1185–1194. doi: 10.1007/s12026-016-8876-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker H, Dragunow M, Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Requirements for NADPH oxidase and myeloperoxidase in neutrophil extracellular trap formation differ depending on the stimulus. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:841–849. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1211601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rochael NC, et al. Classical ROS-dependent and early/rapid ROS-independent release of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps triggered by Leishmania parasites. Scientific reports. 2015;5:18302. doi: 10.1038/srep18302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lood C, Arve S, Ledbetter J, Elkon KB. TLR7/8 activation in neutrophils impairs immune complex phagocytosis through shedding of FcgRIIA. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2103–2119. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunderson CW, Seifert HS. Neisseria gonorrhoeae elicits extracellular traps in primary neutrophil culture while suppressing the oxidative burst. mBio. 2015;6 doi: 10.1128/mBio.02452-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Handing JW, Criss AK. The lipooligosaccharide-modifying enzyme LptA enhances gonococcal defence against human neutrophils. Cellular microbiology. 2015;17:910–921. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jean S, Juneau RA, Criss AK, Cornelissen CN. Neisseria gonorrhoeae Evades Calprotectin-Mediated Nutritional Immunity and Survives Neutrophil Extracellular Traps by Production of TdfH. Infect Immun. 2016;84:2982–2994. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00319-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juneau RA, Stevens JS, Apicella MA, Criss AK. A thermonuclease of Neisseria gonorrhoeae enhances bacterial escape from killing by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:316–324. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hou S, et al. Chlamydial plasmid-encoded virulence factor Pgp3 neutralizes the antichlamydial activity of human cathelicidin LL-37. Infect Immun. 2015;83:4701–4709. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00746-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang L, et al. Chlamydia-secreted protease CPAF degrades host antimicrobial peptides. Microbes Infect. 2015;17:402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song HO, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis: reactive oxygen species mediates caspase-3 dependent apoptosis of human neutrophils. Experimental parasitology. 2008;118:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boily MC, et al. Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2009;9(09):118–129. 70021–0. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez-Garcia M, Barr FD, Crist SG, Fahey JV, Wira CR. Phenotype and susceptibility to HIV infection of CD4+ Th17 cells in the human female reproductive tract. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:1375–1385. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez-Garcia M, Fortier JM, Barr FD, Wira CR. Aging impacts CD103(+) CD8(+) T cell presence and induction by dendritic cells in the genital tract. Aging cell. 2018 doi: 10.1111/acel.12733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez-Garcia M, Fortier JM, Barr FD, Wira CR. Isolation of Dendritic Cells from the Human Female Reproductive Tract for Phenotypical and Functional Studies. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2018 doi: 10.3791/57100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forthal DN, et al. IgG2 inhibits HIV-1 internalization by monocytes, and IgG subclass binding is affected by gp120 glycosylation. AIDS. 2011;25:2099–2104. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b64bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, et al. Characterization of antibody responses elicited by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate trimeric and monomeric envelope glycoproteins in selected adjuvants. J Virol. 2006;80:1414–1426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1414-1426.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ochiel DO, et al. Uterine epithelial cell regulation of DC-SIGN expression inhibits transmitted/founder HIV-1 trans infection by immature dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gelderblom HC, et al. Viral complementation allows HIV-1 replication without integration. Retrovirology. 2008;5:60. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-60. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-5-60 1742-4690-5-60[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ochsenbauer C, et al. Generation of transmitted/founder HIV-1 infectious molecular clones and characterization of their replication capacity in CD4 T lymphocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. J Virol. 2012;86:2715–2728. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06157-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edmonds TG, et al. Replication competent molecular clones of HIV-1 expressing Renilla luciferase facilitate the analysis of antibody inhibition in PBMC. Virology. 2010;408:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodriguez-Garcia M, et al. Estradiol Reduces Susceptibility of CD4(+) T Cells and Macrophages to HIV-Infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062069. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062069 PONE-D-12-33736[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lahm HW, Stein S. Characterization of recombinant human interleukin-2 with micromethods. J Chromatogr. 1985;326:357–361. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)87461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary video 1. Genital neutrophils release NETs after stimulation with HIV-VLPs.

Supplementary video 2. Unstimulated control neutrophils. Genital neutrophils plated under the same conditions as those shown in supplementary video 1, but no HIV-VLPs added.

Supplementary video 3. DNAse control. Genital neutrophils stimulated with HIV-VLPs in the presence of DNAse. DNAse prevents the formation of NETs and HIV entrapment.