Abstract

Objectives:

Electronic health records (EHRs) present healthcare delivery systems with scalable, cost-effective opportunities to promote lifestyle programs among patients at high risk for type 2 diabetes, yet little consensus exists on strategies to enhance patient engagement. We explored patient perspectives on program outreach messages containing content tailored to EHR-derived diabetes risk factors—a theory-driven strategy to increase the persuasiveness of health communications.

Study Design:

Convergent mixed methods.

Methods:

Within an integrated healthcare delivery system, women with a history of gestational diabetes participated in 1 of 6 ethnic-specific focus groups to elicit diverse perspectives, and a survey yielding quantitative data to contextualize qualitative responses.

Results:

The sample included 35 participants (80% racial/ethnic minorities; (mean age = 36) years). Themes regarding tailored messages centered on diabetes risk communication (opposing attitudes about whether to feature diabetes risk factors), privacy (how and whether patient data should be accessed), authenticity (perceiving messages as personalized vs “generically” computer generated), and preferences for messages sent by one’s personal physician. Trust in the medical profession and perceived risk for diabetes were similar to levels reported in comparable samples.

Conclusions:

Patient reactions highlight the challenges of leveraging EHRs for tailored messages. Some viewed messages as caring reminders to take preventive action and others raised concerns over intrusiveness. Optimal lifestyle program outreach to improve quality of care for women at high risk for diabetes may require communication from personal physicians, careful development to mitigate concerns over privacy and authenticity, and techniques to counteract the threatening nature of personalized risk communication.

Précis:

Divergent reactions among women at high risk for diabetes highlight challenges of implementing tailored outreach messages, driven by electronic health records, to promote patient engagement in preventive lifestyle programs.

Lifestyle programs, or behavioral interventions for weight management, healthy eating, and physical activity, can prevent type 2 diabetes (T2D)1,2 and are recommended for high-risk adults.3–5 Such programs are offered by healthcare delivery systems, yet little consensus exists on strategies to enhance patient engagement. Expanding the modest uptake observed in large health systems6,7 could further increase the programs’ public health impact. These programs are particularly vital for women with a history of gestational diabetes (GDM). Despite high rates of progression from GDM to T2D,8 many women may not appreciate this risk,9 and healthcare providers may be unaware of patients’ GDM history due to fragmented care. Such factors potentially influence low program uptake in this high-risk population. Of further concern, considering racial/ethnic disparities in GDM10 and progression to T2D,11 minority participation in lifestyle programs appears low12,13 and minorities appear less likely to use recommended approaches to lifestyle changes.14–16

Electronic health records (EHRs) present opportunities to promote lifestyle programs using tailored messages. In contrast to broad patient outreach, tailored outreach—using messages with content personalized to an individual patient based on demographic, behavioral, and/or theoretical constructs17—is a well-established, theory-based strategy for increasing the persuasiveness,17 appeal,18–20 and effectiveness21 of health communications, which may also foster meaningful use of EHRs.22,23 For example, beyond identifying recipients for a given message, patient-level EHR data could be used to personalize the content of that message (eg, by referencing a specific patient’s combination of disease risk factors). Automated tailoring has potential as a cost-effective strategy that can be delivered consistently in large health systems, which are key advantages given the potential expense of recruiting eligible patients to available programs.4 Still, concerns about privacy call for caution.24 Furthermore, tailored content in messages inviting participation in a lifestyle program could backfire by linking key aspects of the self to negative disease states,25,26 resulting in defensive resistance and dismissal of threatening information.25,27,28 Patient input is thus critical to inform implementation.

Given gaps in the patient engagement literature, we examined perspectives on tailored outreach messages encouraging women at high risk for T2D to participate in health system-based lifestyle programs. We took a mixed methods approach to obtain more comprehensive patient perspectives29 and inform future research to disseminate evidence-based lifestyle interventions.30

METHODS

Design

Using a convergent mixed methods design, we collected qualitative data via focus groups and quantitative data via survey in 2015. Quantitative data served to describe the sample and contextualize focus group responses.

Setting

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a large integrated healthcare delivery system serving 3.7 million members who are demographically similar to the underlying population, except at the extremes of income and education.31

Participants

The sampling frame consisted of nearly all women diagnosed with GDM in 2011 to 2012 across 44 KPNC medical facilities. These women were previously identified as part of “Gestational Diabetes’ Effects on Moms” (GEM), a pragmatic cluster randomized clinical trial comparing postpartum T2D prevention strategies. Cluster randomization at the facility level had assigned women to usual care or a 13-session postpartum lifestyle intervention offered as optional routine care on behalf of the health system.32,33 Here, we used stratified sampling within the GEM cohort to identify women from 6 ethnic groups representative of Northern California and among those with the highest prevalence and/or absolute frequencies of GDM.10 Eligibility criteria included age 18 to 50 years; comfort reading and speaking English; not currently pregnant; absence of recognized overt diabetes, confirmed by the KPNC diabetes registry34 and self-report; and body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 40 kg/m2 among African American, Mexican American, and non-Hispanic white women, and 23 to 40 kg/m2 among Asian Indian, Chinese American, and Filipina women who are at greater risk for diabetes at a lower BMI.35

Procedure

Recruitment included a letter/e-mail followed by telephone invitation, and a $40 incentive. Participants provided written or verbal consent, including permission to link data with GEM. Both studies were approved by the KPNC Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

Quantitative.

Self-reported demographic characteristics, participation in a health system-based lifestyle program in the last 6 months (yes/no), and likelihood of participating in the next 6 months (on a 4-point scale ranging from very likely to very unlikely) were assessed using single items. Patient trust in the medical profession was assessed using a validated 5-item questionnaire; summed responses on a 5-point scale range from 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating greater trust.36 Perceived risk for developing diabetes in the next 10 years was assessed using an item originally derived from the validated Risk Perception Survey for Developing Diabetes (RPS-DD).37 Responses on this 4-point scale range from almost no chance to high chance, with higher scores indicating greater perceived risk. Personal control over developing diabetes was assessed using a 4-item RPS-DD subscale. Averaged responses on a 4-point scale range from 1–4, with higher scores indicating greater control. Data from GEM included time elapsed since delivery of the index GDM pregnancy; GEM condition assignment (ie, being in a facility assigned to usual care versus intervention); and whether women in facilities assigned to the GEM intervention had participated in at least 1 session.32

Qualitative.

Focus group methods were explicitly chosen to elicit an array of ideas among participants from diverse backgrounds. Rather than interpreting results as confirming consensus or strength of endorsement of specific ideas, qualitative themes can suggest topics for future hypothesis-testing research.

Two researchers co-moderated 6 ethnic-specific focus groups among African American, Asian Indian, Chinese American, Filipina, Mexican American, and non-Hispanic white women. We conducted 1 group in person and 5 via Web-enabled conference calls to maximize participation across a large geographical area. A standardized semi-structured interview protocol using the same moderator prompts38 and predetermined open-ended questions enhanced consistency, neutrality, and comparability of responses across groups.39 Key questions explored outreach message content that would help women decide whether to participate in a lifestyle program, and the acceptability of individually tailored messages using EHR data. As a sub-section of the latter topic, participants were asked about the message sender and inclusion of personal diabetes risk factors available in EHRs: history of GDM, blood glucose laboratory results, weight status, and ethnicity (for racial/ethnic minority women). To facilitate discussion, participants were asked about their reactions to a 280-word hypothetical tailored message addressed to a fictional patient that referenced the personal risk factors noted above; the message was purportedly co-signed by the clinical director of a lifestyle program and department chief of obstetrics/gynecology, and delivered via secure e-mail. Focus groups were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed, verbatim.

Analyses

Quantitative data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc; Cary, North Carolina). We tested for group differences in patient trust, perceived risk for diabetes, and personal control using relevant tests for small sample sizes (eg, Kruskal-Wallis and Fisher’s exact tests). Qualitative data were analyzed using NVivo 10 software (QSR Intl Pty Ltd; Doncaster, Australia) and thematic analysis40 to inductively and deductively derive themes from the data.41 A doctoral-level clinical psychologist and master’s-level researcher reviewed all transcripts to develop a coding scheme of broad meaningful themes. One researcher independently coded transcripts; 2 researchers together then reviewed all coded text and selected key quotes, with discrepancies resolved by consensus. Finally, we integrated quantitative and qualitative data by creating joint displays.42

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Recruited participants (N = 35) had a mean age of 36 years (standard deviation [SD] = 5.3), and were a mean of 3.6 (SD = 0.3) years postpartum from their index GDM pregnancy. As designed, the sample was ethnically diverse (Table 1). Mean patient trust in the medical profession was 16.6 (SD = 3.8). Regarding perceived risk, 17% (n = 6) believed they had a high chance of developing diabetes, 29% (n = 10) a moderate chance, 49% (n = 17) a slight chance, and 6% (n = 2) almost no chance. Mean personal control over developing diabetes was 3.4 (SD = 0.5). Whereas 6% (n = 2) reported participating in a health system-based lifestyle program in the last 6 months, many endorsed intentions for the next 6 months with 69% (n = 24) somewhat or very likely, and 31% (n = 11) somewhat or very unlikely to participate. There were no significant differences across focus groups in any of the above domains (P ≥.07). Of 17 women in facilities assigned to the GEM intervention, 88% (n = 15) had participated in at least 1 session; participation was 50% among Filipina women (n = 2/4) and 100% within all other groups.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Racial/ethnic origina | ||

| African American | 5 | 14 |

| Asian Indian | 6 | 17 |

| Chinese American | 4 | 11 |

| Filipina | 6 | 17 |

| Mexican American | 7 | 20 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 7 | 20 |

| Nativity | ||

| Born outside the United States | 11 | 31 |

| Born in the United States | 22 | 63 |

| Missing | 2 | 6 |

| Educational level | ||

| Some college, 2-year college, or technical school |

10 | 29 |

| ≥4-year college | 25 | 71 |

| Household income | ||

| <$50,000 | 3 | 9 |

| $50,000 to $99,999 | 15 | 43 |

| ≥$100,000 | 16 | 46 |

| Missing | 1 | 3 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 23 | 66 |

| Part time or student | 3 | 9 |

| Not employed outside the home | 9 | 26 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living with partner | 33 | 94 |

| Not married or living with partner | 2 | 6 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| 23 to <25b | 3 | 9 |

| 25 to <30 | 16 | 46 |

| ≥30 | 16 | 46 |

| GEM condition assignment | ||

| Usual care | 18 | 51 |

| Intervention | 17 | 49 |

GEM indicates Gestational Diabetes’ Effects on Moms trial.

Includes 3 multi-ethnic women (Chinese Vietnamese; Chinese Japanese; Mexican Puerto Rican).

At-risk category applicable to Asian women only (ie, Asian Indian, Chinese American, and Filipina).35

Qualitative Findings

Six broad themes emerged regarding tailored content in outreach messages, encompassing preferences and concerns. Sample quotes and the focus groups in which each theme emerged appear in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient Perspectives on Tailored Messages: Qualitative Themes, Sample Quotes, and Focus Groups in Which Themes Emerged

| Preferences for tailored outreach messages | Concerns about tailored outreach messages | |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy | ||

| “…if I did receive this as a real letter today, I would be happy. I would feel good about it because it feels like I’m not lost in the whole network of being a [health system] patient…I’m not really concerned about the privacy because this is all within [the health system].” Focus groups (3): Filipina; Mexican American; non-Hispanic white |

“…it concerns me that it had so much information about my health. And I’m assuming it’s a template format that someone is kind of typing it in, sort of like, oh, it probably has like a database, and then all my health information is there. I will be wondering who typed up this letter. And it’s probably not my doctor who wrote this. It has to be somebody out there who somehow has my health record and is mailing this out to me…I did not like it at all.” Focus groups (2): Chinese American; Filipina |

|

| Authenticity | ||

| • “This way, someone is coming to me and saying, ‘Hey, you know, we know that you had gestational diabetes, you know, we want to help you with preventative care,’ which I love the idea that we’re getting the support and someone is reaching out, that it’s personal. It’s not like a generalized letter that’s going to a bunch of people…I think the personal touch is actually something that would draw me in, versus a general letter.” • “I liked it. It’s personal. It makes me feel like, ‘Oh, wow, someone’s checking in on me.’ So, it feels really good that you have our personal information on there.” Focus groups (5): African American; Asian Indian; Filipina; Mexican American; non-Hispanic white |

• “[The message is] very generic, right? It’s very impersonal. It’s like just mad libs, you know, and you fill in the blank.” • “…it’s endorsed by doctors. You have the clinical director of the [program] and you have the chief of the OB/GYN department…it’s vetted. It’s not like from some random person. So, that’s good, but at the same time, I don’t have any illusions that they know who I am and that they sent this to me. Like I know this is—[the health system is] very big. So, I know it’s created by—generically, really, by computers and whatnot….” Focus groups (4): Asian Indian; Chinese American; Filipina; non-Hispanic white |

|

| Sender | ||

| Personal Physician |

• “I would read this if it comes from my personal physician.” • “…I really took it from a good place because it’s coming from my healthcare provider, from my doctors, who have the utmost, you know, concern and, you know, respect for my health. And they’re addressing me personally with data and information that is absolutely true. And I just felt like, ‘Wow, they really care!’” Focus groups (6): All |

(None) |

| Non- Personal Physician |

• “…I don’t really see my doctor as [sic] often. Maybe I should, but to know that they’re – the higher-ups are involved in caring for my wellness, that – it’s important to me.” • “Everyone’s working towards your benefit, the way I look at it. That’s been my experience with [the health system].” Focus groups (3): African American; Chinese American; Filipina |

• “If it was from my specific doctor…it kind of would trigger me more, instead of just…a different team that I’m not used to.” Focus groups (3): Asian-Indian; Chinese American; Filipina |

| Risk communication | ||

| “I see it definitely being, you know, ‘Hey, we’re all part of that— we’re all concerned, and you know, we see this. Let’s again talk about it, let’s get it—let’s work on it, get it fixed.’” Focus groups (5): African American; Asian Indian; Filipina; Mexican American; non-Hispanic white |

“Not taunting. I mean, I know that’s not really the purpose or the intention. But it’s—say somebody has a blemish on their face and that person knows it, and then another person like points it out. It’s, like, ‘Gee, thanks.’” Focus groups (2): Chinese American; non-Hispanic white |

|

| Clinical risk factors | ||

| • “My gestational diabetes is something I do not think about. I mean, I literally forgot about it, and I went about my life and busy, and you know, eating kind of whatever I wanted. I just never thought about it, you know, so it’s definitely a good reminder.” • “It’s certainly not appealing [laughs] to be reminded you’re overweight. But, you know, I actually thought about this but it is not concerning because it’s just the truth…it kind of, you know, kind of urges you to take action because of the truth.” Focus groups (5): African American; Asian-Indian; Filipina; Mexican American; non-Hispanic white |

• “…I’m struggling with my weight. I know I need to exercise, and here you are, like, poking me. So, I feel like sad, you know, reaction kind of, like, annoyed. Like ‘Yeah, indeed, I do need – I mentioned my blood sugar is high and I am at a risk for diabetes…’ It’s kind of depressing.” • “…if we went through [gestational diabetes] before, we know that we need to be careful…the first time I read it, I found myself, like, I kind of stopped at that point and had to go back and re-read it because it distracted me from the positive of, ‘We have this great service that we want to offer you.’” Focus groups (3): Chinese American; Filipina; non-Hispanic white |

|

| Ethnicity as a risk factor | ||

| • “…it’s medical evidence. There are things that affect certain races, certain genders, more than others. And let’s just put the facts on the table…you can’t combat the truth. This is the truth. Let’s work on it.” • “I actually thought that it was nice that they were focusing on problems that we have as a culture, that I have as an individual; and certainly being of Latina origin, that plays a role in my health. So, I think it’s a relevant factor.” Focus groups (4): African American; Asian Indian; Filipina; Mexican American |

• “I know I’m fat. I know I’m Chinese American and I know I have a family history of diabetes, that it’s a risk. So, the letter’s telling me things that I know, not necessarily like the most flattering things, and that I need to do something about it. Like, I know that! So, I’m not sure how effective stating this information is.” Focus groups (3): Asian Indian; Chinese American; Mexican American |

|

Privacy.

According to one perspective, tailored messages are acceptable and nonintrusive—as long as they are sent securely, by their personal physician, and/or within the boundaries of the health system. As one participant described these tensions related to privacy,

“…to sort of pinpoint the people that would most benefit from a [program]…the only way to do that is to get some of that information together about the different people to see who would be the ones that would benefit the most. So, I understand that it’s sort of a really tricky balance between that privacy, but also establishing the access to these programs…it’s a very tricky balance because sometimes those of us who need it most aren’t that quick…to go and get that help.”

Concerns over privacy included wariness about the number of people who might have access to one’s medical records; still, participants acknowledged the advantages of such broad access (eg, the ability to receive integrated care from multiple providers).

Authenticity.

Some participants perceived tailored messages as personal, appealing, and persuasive, creating a sense of authenticity that was interpreted as a genuine expression of professional care—that is, appreciating that “someone took the time to see what my information is.” In contrast, others perceived tailored messages as impersonal, generic, or spam, unlikely to be opened or read; and expressed disdain for ostensibly computer-generated content.

Sender.

Participants perceived their physician as trustworthy and concerned about their health, and noted that they were more likely to read a tailored message that came directly from that individual. Positive viewpoints also emerged about senders other than a personal physician, founded on the notion that the entire health system is working collaboratively for one’s benefit as a patient. Negative viewpoints about senders other than a personal physician were tied to concerns about privacy, inauthenticity, and perceptions that such messages would lack the caring or potential for follow-up offered by one’s physician.

Risk communication.

Participants described preferences for strong, clear, and hopeful messages that clearly communicated their risk for diabetes and actions needed to prevent it, thus empowering women with the information and resources needed to “get it fixed.” Subthemes included the appeal of messages that recognized women’s past efforts to take good care of their health; and a suggestion that messages should convey a sense of urgency. Contrasting perspectives included negative reactions to diabetes risk communication, including taking offense at messages perceived as unhelpful and “telling me what I already know.”

Clinical risk factors.

According to one perspective, inclusion of diabetes risk factors such as history of GDM, laboratory results, and weight status was viewed as a caring and persuasive basis upon which to recommend preventive programs. Participants described having “forgotten” that they had a history of GDM and regarded even “unappealing” risk factor information as an important health reminder—particularly in the context of being asymptomatic and engrossed in the competing demands of day-to-day life. A contrasting perspective viewed risk factors as an unwelcome reminder of a physically and emotionally difficult time of life (as standard GDM treatment involves intensive glucose monitoring and control via diet, physical activity, and, occasionally, medication43). Subthemes included feelings of sadness, upset, and taking offense—or imagining that others might take offense, even if they themselves did not—and preference for messages that focus on the program being offered, rather than recipients’ medical histories.

Ethnicity as a risk factor.

Perspectives regarding the mention of ethnicity as a diabetes risk factor included seeing it as relevant, useful, and offering a more complete picture of risk factors that acknowledge cultural influences on health, beyond a sole focus on individual choices. Contrasting perspectives included viewing it as uninformative and potentially reflecting cultural stereotypes about health behaviors (eg, negative perceptions of ethnic food preferences).

Programmatic message content.

In addition to themes relevant to tailored message content, participants preferred that messages specify a range of both program features (eg, cost, staff expertise, behavior change techniques used), and program outcomes (benefits of participating, such as anecdotal and quantitative evidence of effectiveness). The first theme emerged across all focus groups; the second emerged in groups with Asian Indian, Chinese American, Mexican American, and non-Hispanic white women.

Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

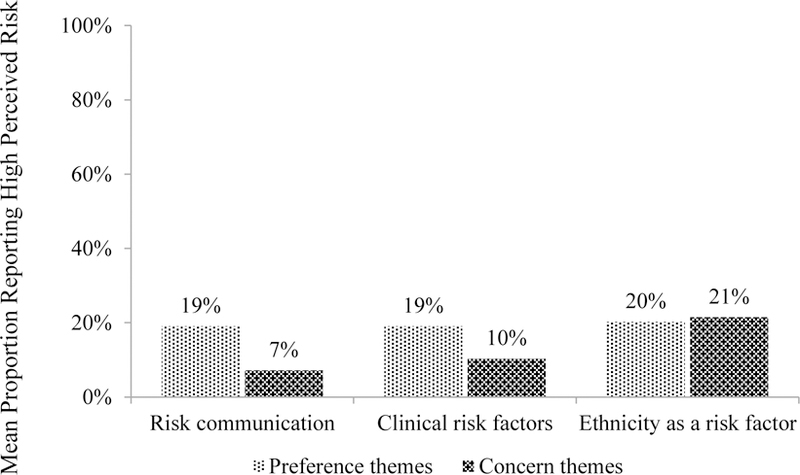

We created 2 descriptive joint displays: one addressing diabetes risk and another addressing trust. The Figure displays the mean proportions of women reporting high perceived risk for diabetes, across the focus groups in which risk-related themes emerged. Proportions were somewhat greater across focus groups that expressed preferences for risk information compared with concerns. For example, 19% of women reported high perceived risk in groups that expressed preferences for tailored messages containing clinical risk factors versus 10% in groups that expressed concerns. Patient trust did not differ markedly between groups that expressed preferences versus concerns related to privacy, authenticity, and the trustworthiness of senders (data not shown). For example, trust scores averaged 15.8 across groups that expressed privacy-related preferences and 16.7 across groups that expressed privacy-related concerns.

Figure.

Joint Display of Quantitative Perceived Risk for Diabetes and Qualitative Risk-Related Themes (N=6 focus groups; N=35 participants)a,b

aBars indicate the mean proportion of women reporting high perceived risk for diabetes, across the focus groups in which each theme emerged.

bData are not mutually exclusive (eg, both preference and concern themes may have emerged in each focus group).

DISCUSSION

Although EHR-driven, tailored messages have potential as an efficient and cost-effective outreach strategy, divergent patient reactions highlight key challenges. In the present study, diverse women at high risk for T2D raised contrasting ideas about privacy and authenticity. Participants appreciated the size and complexity of integrated health systems and appeared savvy about the ways in which tailored messages could be generated. Yet, whereas some were unconcerned about security, others were strongly critical. Indeed, prior research shows that patients endorse opposing views of what EHR data they want made available to their healthcare team,44 and a substantial proportion remain concerned about the privacy of EHRs.45 Seeking input from patient stakeholders and explicitly addressing these issues in tailored messages, (eg, by stating how and by whom they have been generated and sent—preferably, by personal physicians) could enhance acceptability and maintain trust.

In terms of risk communication, some participants welcomed it as a caring prompt for preventive action whereas others viewed it as unhelpful, uninformative, or an unpleasant reminder of challenges related to lifestyle behavior change. Similarly, some minority participants appreciated the mention of ethnicity as a diabetes risk factor to acknowledge culture’s impact on health; others raised concerns over stereotyping. These perspectives related to risk factors highlight, first, the complexities of developing sensitive and culturally relevant communications.46 Second, results echo literature on the threatening nature of personally-relevant health messages.27,28 It is possible that this effect could be counteracted by self-affirmation,25 a technique shown to increase attention to diabetes risk information,47 in which individuals reflect on a positive aspect of the self. Third, results suggest the need for a positive tone and careful use of clinical information. Patients’ desire for messages that highlight the benefits of lifestyle programs corroborates theoretical48 and empirical49 emphasis on positive consequences and developing favorable expectations (e.g., gain-framed messaging) to promote new preventive behaviors. Future research should determine whether theory-based approaches such as self-affirmation and gain-framed messaging could mitigate negative reactions to tailored risk communication and increase patient engagement in preventive services. Of note, descriptive findings integrating quantitative and qualitative data raise the possibility that higher self-reported perceived risk may be associated with greater openness to tailored risk communication. If confirmed, health systems could consider surveying patient subsamples to estimate the acceptability of such messages.

Some themes emerged consistently across focus groups (eg, preferences for physician senders), whereas others emerged across fewer groups (eg, concerns about risk communication). Often, the same groups expressed both positive and negative viewpoints signaling within-group heterogeneity (ie, viewpoints differing from person to person), ambivalence about tailored approaches (ie, the same person expressing conflicting viewpoints), or both. Exceptions include focus groups with Chinese American women, in which themes more often clustered around concerns; and African American women, in which themes more often clustered around preferences. Still, such comparisons must be tentative given that the data came from single focus groups for each racial/ethnic background. While qualitative focus group methods are well suited to eliciting the range of ideas about a phenomenon, identifying issues worthy of further investigation, and developing hypotheses, they should be followed by hypothesis-testing research to make definitive cross- and within-group comparisons.

Limitations and Strengths

Study limitations include the sample’s relatively high level of education, their membership in a single health system, and, as noted, our limited ability to make cross-group comparisons. Strengths include stratified sampling by race/ethnicity and ethnic-specific focus groups to foster a range of diverse perspectives; and the mixed methods design, whereby quantitative data provided context in which to interpret qualitative themes. For example, evidence that participants’ trust in the medical profession was similar to a national sample,36 and between focus groups describing preferences versus concerns about privacy and authenticity suggests that these themes did not arise from undue suspicion. Similarly, perceived risk for, and personal control over, diabetes, reflected levels in comparable samples.9 Of note, the sample was evenly split between women who had, and had not, been offered a lifestyle intervention in the GEM trial. In responding to focus group prompts, women in the former category may have drawn on their direct experience of having received outreach messages in that context.

CONCLUSIONS

In an era of “big data,” health systems are well-poised to discover ways of leveraging increasingly prevalent and powerful EHRs to engage high-risk patients. Results among women at high risk for diabetes suggested that patients acknowledge both the advantages and pitfalls of tailored approaches to outreach. Optimal outreach may require communication from personal physicians, mitigating privacy and authenticity concerns, and applying theory-based approaches to counteract the threatening nature of personalized risk communication.

Takeaway Points.

Electronic health records (EHRs) present healthcare delivery systems with scalable opportunities to promote preventive lifestyle programs using tailored outreach. We examined perspectives on program outreach messages tailored to EHR-derived diabetes risk factors among women at high risk for type 2 diabetes.

Themes from focus group discussions included opposing attitudes about whether to feature diabetes risk factors, how and whether patient data should be accessed, and perceived authenticity of tailored messages.

Participants consistently preferred messages sent by a personal physician.

Optimal outreach may require communication from personal physicians, addressing concerns over privacy and authenticity, and mitigating the threatening nature of personalized risk communication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants and analysts Emily Han, MPH, and Ai-Lin Tsai, MS. The authors also thank Joseph J. Gallo, MD, MPH and Karen M. Emmons, PhD for their scientific input.

Source of Funding: This research was supported by grant K01 DK099404 to Susan D. Brown from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and grant R01 HS019367 to Assiamira Ferrara from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Assiamira Ferrara also received support from grant P30 DK092924 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is the pre-publication version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication in The American Journal of Managed Care® (AJMC®). This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The editors and publisher of AJMC® are not responsible for the content or presentation of the prepublication version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to it (e.g., correspondence, corrections, editorials, etc.) should go to www.ajmc.com or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.

Author Disclosures: The authors report no relationship or financial interest with any entity that would pose a conflict of interest with the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002(6):393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratner RE, Christophi CA, Metzger BE, et al. Prevention of diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes: Effects of metformin and lifestyle interventions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93(12):4774–4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2015;163(11):861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pronk NP, Remington PL; Community Preventive Services Task Force. Combined diet and physical activity promotion programs for prevention of diabetes: Community Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2015;163(6):465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;(suppl 38):S8–S16. doi: 10.2337/dc15-S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao H, Adams SR, Goler N, et al. Wellness Coaching for people with prediabetes: a randomized encouragement trial to evaluate outreach methods at Kaiser Permanente, Northern California, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:E207. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson SL, Long Q, Rhee MK, et al. Weight loss and incidence of diabetes with the Veterans Health Administration MOVE! lifestyle change programme: an observational study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3(3):173–180. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70267-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373(9677):1773–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim C, McEwen LN, Piette JD, Goewey J, Ferrara A, Walker EA. Risk perception for diabetes among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007;30(9):2281–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedderson MM, Darbinian JA, Ferrara A. Disparities in the risk of gestational diabetes by race-ethnicity and country of birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2010;24(5):441–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01140.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiang AH, Li BH, Black MH, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes risk after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2011;54(12):3016–3021. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss EC, Galuska DA, Khan LK, Serdula MK. Weight-control practices among US adults, 2001–2002. Am J Prev Med 2006;31(1):18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burroughs VJ, Nonas C, Sweeney CT, et al. Self-reported weight loss practices among African American and Hispanic adults in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc 2010;102(6):469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai AG, Wadden TA, Pillitteri JL, et al. Disparities by ethnicity and socioeconomic status in the use of weight loss treatments. J Natl Med Assoc 2009;101(1):62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serdula MK, Williamson DF, Anda RF, Levy A, Heaton A, Byers T. Weight control practices in adults: Results of a multistate telephone survey. Am J Public Health 1994;84(11):1821–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baradel LA, Gillespie C, Kicklighter JR, Doucette MM, Penumetcha M, Blanck HM. Temporal changes in trying to lose weight and recommended weight-loss strategies among overweight and obese Americans, 1996–2003. Prev Med 2009;49:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Glassman B. One size does not fit all: the case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med 1999;21:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessels LTE, Ruiter RA, Brug J, Jansma BM. The effects of tailored and threatening nutrition information on message attention. Evidence from an event-related potential study. Appetite 2011;56(1):32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.11.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Updegraff JA, Sherman DK, Luyster FS, Mann TL. The effects of message quality and congruency on perceptions of tailored health communications. J Exp Soc Psychol 2007;43(2):249–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreuter MW, Bull FC, Clark EM, Oswald DL. Understanding how people process health information: a comparison of tailored and nontailored weight-loss materials. Health Psychol 1999;18(5):487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull 2007;133(4):673–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med 2010;363(6):501–504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Department of Health and Human Services. Meaningful use http://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/meaningful-use. Health Information Technology website. Published 2013. Updated July 19, 2016. Accessed October 15, 2013.

- 24.Blumenthal D, Squires D. Giving patients control of their EHR data. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(suppl 1):S42–S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherman DAK, Nelson LD, Steele CM. Do messages about health risks threaten the self? increasing the acceptance of threatening health messages via self-affirmation. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2000;26(9):1046–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schüz N, Schüz B, Eid M. When risk communication backfires: randomized controlled trial on self-affirmation and reactance to personalized risk feedback in high-risk individuals. Health Psychol 2013;32(5):561–570. doi: 10.1037/a0029887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croyle RT, Sun Y-C, Hart M. Processing risk factor information: defensive biases in health-related judgments and memory. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, eds. Symptom Perception in Health and Disease Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997: 261–286. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessels LT, Ruiter RA, Jansma BM. Increased attention but more efficient disengagement: neuroscientific evidence for defensive processing of threatening health information. Health Psychol 2010;29(4):346–354. doi: 10.1037/a0019372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Smith KC. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences National Institutes of Health website. https://obssr.od.nih.gov/training/mixed-methods-research/. Published August 2011. Accessed June 28, 2017.

- 30.Glasgow RE, Emmons KM. How can we increase translation of research into practice? types of evidence needed. Annu Rev Public Health 2007;28(1):413–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon NP. Similarity of the Adult Kaiser Permanente Membership in Northern California to the Insured and General Population in Northern California: Statistics from the 2011California Health Interview Survey https://divisionofresearch.kaiserpermanente.org/projects/memberhealthsurvey/SiteCollectionDocuments/chis_non_kp_2011.pdf. Published June 2015. Accessed June 28, 2017.

- 32.Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Albright CL, et al. A pragmatic cluster randomized clinical trial of diabetes prevention strategies for women with gestational diabetes: design and rationale of the Gestational Diabetes’ Effects on Moms (GEM) study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Brown SD, et al. The comparative effectiveness of diabetes prevention strategies to reduce postpartum weight retention in women with gestational diabetes: the Gestational Diabetes’ Effects on Moms (GEM) cluster randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2016;39:65–74. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Ackerson LM, Selby JV. Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. J Amer Med Assoc 2002;287(19):2519–2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu WC, Araneta MR, Kanaya AM, Chiang JL, Fujimoto W. BMI cut points to identify at-risk Asian Americans for type 2 diabetes screening. Diabetes Care 2015;38(1):150–158. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall MA. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Serv Res 2005;5:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker EA, Mertz CK, Kalten MR, Flynn J. Risk perception for developing diabetes: Comparative risk judgments of physicians. Diabetes Care 2003;26(9):2543–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiernan M, Kiernan NE, Goldberg J. Using standard phrases in qualitative interviews Tipsheet #69. Penn State Cooperative Extension website. http://comm.eval.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=9da20813-dbdc-496d-a9e8-2ea5a9bbd73d&forceDialog=0. Published 2003. Accessed June 14, 2014.

- 39.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strauss A, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res 2013;48(6, pt 2):2134–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Ching J, Kim C, Peng T, Crites YM. Referral to telephonic nurse management improves outcomes in women with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206(6):491.e1-e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz PH, Caine K, Alpert SA, Meslin EM, Carroll AE, Tierney WM. Patient preferences in controlling access to their electronic health records: a prospective cohort study in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(suppl 1):S25–S30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ancker JS, Brenner S, Richardson JE, Silver M, Kaushal R. Trends in public perceptions of electronic health records during early years of meaningful use. Am J Manag Care 2015;21(8):e487–e493. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Koningsbruggen GM, Das E. Don’t derogate this message! Self-affirmation promotes online type 2 diabetes risk test taking. Psychol Health 2009;24(6):635–649. doi: 10.1080/08870440802340156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rothman AJ. Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychol 2000;19(1S):64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallagher KM, Updegraff JA. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med 2012;43(1):101–116. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]