Abstract

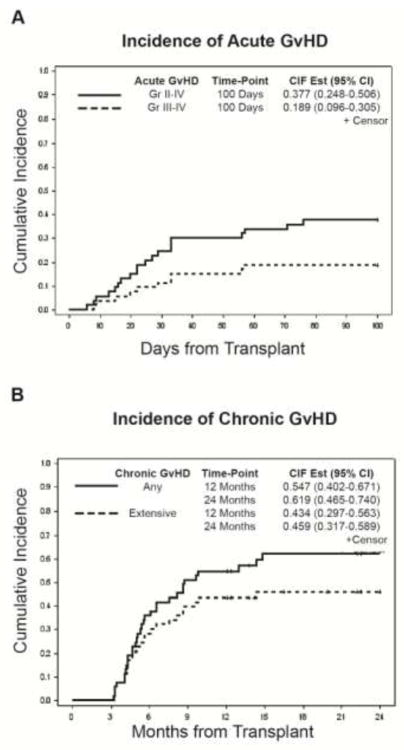

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AlloHCT) is offered increasingly to elderly patients with hematologic malignancies. However, outcome data in those who are 70 years or older are limited, and no standard conditioning regimen has been established for this population. In this retrospective study, we evaluated the outcome of 53 consecutive patients aged 70 years and older who underwent AlloHCT with melphalan (Mel)-based reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) at City of Hope. Engraftment was prompt, with median time to neutrophil engraftment of 15 days. More than 95% of patients achieved complete donor chimerism within 6 weeks from HCT, consistent with “semi-ablative” nature of this regimen. With a median follow up of 31.1 months, the 2-year overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and non-relapse mortality (NRM) were 68.9%, 63.8%, and 17.0%, respectively. Cumulative Incidence (CI) of relapse at 1- and 2-years were 17.0% and 19.3%, respectively. 100-day CI of grade II-IV acute GVHD was 37.7% (grade III-IV: 18.9%), and 2-year CI of chronic GVHD was 61.9% (45.9% extensive). The only significant predictor for poor OS was high/very high disease risk index (DRI). Transplant-related complication/morbidities observed here did not differ from the commonly expected in younger patients treated with RIC. In conclusion; AlloHCT with Mel-based conditioning regimen is associated with acceptable toxicities and NRM, lower incidence of relapse and favorable OS and PFS in patients with 70 years of age or older.

Keywords: allogeneic stem cell transplantation, 70 years and older patients, melphalan-based conditioning regimen

INTRODUCTION

Hematological malignancies are more prevalent in older patients, and due to increased rate of elderly in the population the number of patients presenting with hematological malignancy has increased.1 Median age of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which are the most common indication for allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation (AlloHCT) in this population are 69 and 76 years, respectively.2–4 Despite the advent of the novel agents, AlloHCT remains the only curative option for most of the common hematologic malignancies. This treatment was traditionally limited to younger patients, but with the introduction of reduced intensity conditioning (RIC), availability of donor, improvement of supportive care, and advancements of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis; it is being increasingly employed in older adults.5 However, detailed information on best candidate for this procedure, best conditioning regimen and GVHD prophylaxis to be used, and transplant outcomes does not exist for this unique population.

One of the first case series to report feasibility of alloHCT in 70 years or older adults was done by Brunner et al.6 In this study, 54 patients with median age of 71 years were conditioned primarily with fludarabine and busulfan (FluBu) and received methotrexate (MTX) for GVHD prophylaxis. More than 80% of these patients received transplant from matched unrelated donors (MUD) and more than 70% had HCT- comorbidity index of 2 or less. With a median follow up of 21 months, 2-year non-relapse mortality (NRM) was low at 5.6%, which proved safety and feasibility of this procedure in this older population. However, 2-years progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were both at 39% with a high relapse rate of 56%. In a more recent analysis, transplant utilization and outcomes of the same age population undergoing first alloHCT in the united states from 2008-2013 and were reported to Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) were studied,5 and 2-year OS, PFS and NRM were 39%, 32%, and 33%; respectively.5 In this report, the use of myeloablative conditioning (MAC), and higher HCT-CI was associated with inferior outcomes.

At City of Hope, RIC regimen with fludarabine in combination with melphalan at 140 mg/m2 (FluMel) has been successfully used for various hematologic malignancies.7 In 2 studies by Nakamura et al, among 59 patients with MDS who underwent matched donor HCT with FluMel for conditioning and tacrolimus/sirolimus- (T/S-) based GVHD prophylaxis, 2-year OS, relapsed rate and NRM were 75%, 21%, and 10.5%; respectively.8,9 In another study, patients with T-cell lymphoma who underwent the similar therapy between 2001 and 2008 at the City of Hope, 2-year OS, PFS, and NRM were 55%, 30%, and 22%; respectively.10 The outcome of this very regimen was also reported for patients with high risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia who were unfit to undergo a MAC regimen with 2-year OS, relapse rate and NRM of 61%, 21%, and 21%; respectively.11 Even among patients with myelofibrosis, results were encouraging with a 5-year OS of 65%.12,13

Compared with FluBu, FluMel-based RIC HCT has been associated with better disease control but higher NRM, which results in similar OS amongst these regimens.12–17 Since the previous reports of HCT recipients ages 70 and older were either primarily FluBu18 or included multiple other regimens with only a small fraction of patients (16%) receiving FluMel,5 we sought to determine the characteristics and outcome of a more homogenous population of patients in this age group who underwent HCT with FluMel-based RIC at City of Hope. In addition, we explored other secondary outcomes/morbidities unique to this population such as psychosocial support, confusion and imbalance/falling down during the hospital stay.

METHODS

Study Population

We identified 53 consecutive patients aged 70 or older who underwent AlloHCT at City of Hope National Medical Center (COH) between January 1, 2007 and Dec 31, 2016. Patients who underwent sibling or unrelated AlloHCT for hematologic malignancies using Mel-based conditioning and T/S-based GVHD prophylaxis regimens were included. This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of COH. Eligibility for transplantation was per our institution’s guidelines. Donor choice was per our donor selection committee guidelines.

Definitions

Diagnoses were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) system. HCT-specific comorbidity index (-CI) scores were calculated as described by Sorror et al.19 Disease risk index (DRI) scores were calculated as described by Armand et al.13 Patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) had cytogenetic risk documented as described by the National Cancer Research Institute Adult Leukemia Working Group.14 The primary outcomes were relapse rate, NRM, PFS, modified GVHD- and relapse- free survival (mGRFS) and OS. NRM was defined as any cause of death occurring after transplantation without documented relapse. Relapse was defined as relapse with or without death. PFS was defined as the time from stem cell infusion until the date of relapse or death, whichever occurred first. mGRFS was defined as the time from transplantation until the date of either grade III–IV acute GVHD, moderate-severe chronic GVHD, disease relapse, or death from any cause.20 OS was defined as the time from transplantation until the date of death. Patients who were alive at the time of our analysis were censored at the last known alive date. Neutrophil engraftment was defined as the first day of an absolute neutrophil count >500/uL on 3 consecutive measurements. Platelet recovery was defined as the first day of 2 consecutive measurements of >20,000/uL without transfusion support in the prior 7 days. All patients received T/S- based regimens as GVHD prophylaxis. In general, taper of immune suppression was initiated 4 months after transplantation in the absence of active GVHD, with the goal of immunosuppression cessation by approximately 6 to 8 months after HCT. Acute GVHD was graded by consensus grading criteria,15 and chronic GVHD was defined clinically by treating physicians. Grading of the severity of cGVHD was defined as limited or extensive according to the Seattle criteria.21 Infectious complications (within the first 100 days) that included blood stream infections (BSI) were reviewed as: true bacteremia versus blood culture contamination, invasive fungal infections (IFI) per definitions from the European organization of research and treatment of cancer/ Mycoses study group (EORTC/MSG) consensus group22 and viral infections.

Assessment of pre-HCT muscle mass

Twenty six out of 53 patients had a CT scan performed within 30 days of the start of HCT conditioning, allowing us to assess muscle mass via an established medical analysis software (SliceOmatic software; Tomovision, Quebec, Canada). Of note, there were no significant differences in patient and treatment characteristics between patients with and without pre-HCT scans (Supplementary 1). The third lumbar vertebra (L3) was used as a standard landmark, because this correlates best with whole-body muscle mass.23,24 Muscles were quantified within a Hounsfield unit (HU) range of −29 to 150 HU (methodology detailed in Supplementary data). Muscle area was normalized for height in meters squared (m2) and reported as lumbar SMI (cm2/m2). Mean muscle attenuation MA (HU) was reported for the entire muscle area at the third lumbar vertebra. Sex and BMI-specific cutoff values of low SMI and MA25,26 were used to identify patients with abnormal muscle mass (having both low SMI and MA) prior to HCT.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to show baseline patient demographic and disease characteristics, donor type, and donor/recipient gender match, blood ABO compatibility, and CMV serostatus at the time of transplantation. Kaplan-Meier curves were used for estimating OS and PFS, and their differences by patient and/or donor characteristics were tested using the log-rank test. Cumulative incidence curves of relapse, NRM, acute and chronic GVHD were estimated using the method of completing risks and compared using Gray’s test. Relapse and NRM were competing risks events for each other. For acute and chronic GVHD, relapse and NRM were competing risks events.

SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to conduct the analyses. All tests were 2 sided at a significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Table 1 demonstrates the patient and transplant characteristics of 53 patients aged ≥70 who underwent AlloHCT in COH from 2007 to 2016 and received melphalan-based RIC HCT. In summary, patients median age was 71 (range: 70–78). A majority of the patients had AML (n=27) or MDS (n=14). Karnofsky performance status was ≥70% in all patients. Almost all patients received peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) as graft source (n=51) and T/S-based regimen for GVHD prophylaxis (n=53).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N=53)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age at HSCT, years | |

| Median (range) | 71 (70–78) |

| Interquartile range | 70 to 72 |

| 70 | 19 (35.8%) |

| 71 | 14 (26.4%) |

| ≥72 | 20 (37.7%) |

| Recipient sex | |

| Male | 35 (66.0%) |

| Female | 18 (34.0%) |

| Year of HSCT performed | |

| 2007 | 1 (1.9%) |

| 2008 | 4 (7.5%) |

| 2009 | 4 (7.5%) |

| 2010 | 2 (3.8%) |

| 2012 | 6 (11.3%) |

| 2013 | 4 (7.5%) |

| 2014 | 8 (15.1%) |

| 2015 | 13 (24.5%) |

| 2016 | 11 (20.8%) |

| Donor type | |

| HLA Identical sibling | 11 (20.8%) |

| HLA Matched, unrelated (8/8) | 38 (71.7%) |

| HLA Mismatched, unrelated (3 pts 7/8, 1 pt >1 mismatch) | 4 (7.5%) |

| Donor age, years | 33 (19–78) |

| HLA Identical sibling, median (range) | 67 (60–78) |

| HLA Matched, unrelated, median (range) | 29.5 (19–59) |

| HLA Mismatched, unrelated, median (range) | 25.5 (23–38) |

| Donor sex | |

| Male | 35 (66.0%) |

| Female | 18 (34.0%) |

| Female donor to male recipient (gender mismatch) | |

| Yes | 12 (22.6%) |

| No | 41 (77.4%) |

| Donor Previous Pregnancy | |

| 0 | 8 (53.3%) |

| ≥ 1 | 7 (46.7%) |

| Missing | 3 |

| ABO compatibility | |

| ABO compatible | 25 (47.2%) |

| Minor incompatible (donor is O and recipient is A, B, or AB) | 13 (24.5%) |

| Major incompatible (Recipient is O and donor is A, B, or AB) | 6 (11.3%) |

| Bidirectional (None are O) | 9 (17.0%) |

| Graft type | |

| Peripheral blood stem cells | 51 (96.2%) |

| Bone marrow | 2 (3.8%) |

| Disease diagnosis at HSCT | |

| AML (12 CR1, 5 CR2, 3 RL1, 6 IF, 1 UNT) | 27 (50.9%) |

| MDS (2 CR, 4 RA, 7 RAEB, 1 MDS/MPD) | 14 (26.4%) |

| MPN | 6 (11.3%) |

| Lymphoma (1 IF, 1 CR2) | 2 (3.8%) |

| ALL (2 CR1) | 2 (3.8%) |

| BPDCN (1 CR1) | 1 (1.9%) |

| APL (1 RL3) | 1 (1.9%) |

| DRI score | |

| Low | 8 (15.1%) |

| Intermediate | 26 (49.1%) |

| High | 18 (34.0%) |

| Very High | 1 (1.9%) |

| Recipient / donor CMV serostatus | |

| Negative / Negative | 12 (22.6%) |

| Negative / Positive | 4 (7.5%) |

| Positive / Negative | 20 (37.7%) |

| Positive / Positive | 17 (32.1%) |

| Karnofsky performance status % | |

| 100 | 12 (22.6%) |

| 90 | 23 (43.4%) |

| 80 | 15 (28.3%) |

| 70 | 2 (3.8%) |

| Missing | 1 (1.9%) |

| HCT comorbidity index | |

| Median (range) | 2 (0–9) |

| Interquartile range | 0 to 3 |

| 0 | 20 (39.2%) |

| 1–2 | 10 (19.6%) |

| ≥3 | 21 (41.2%) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| Fludarabine / Melphalan | 48 (90.6%) |

| Clofarabine / Melphalan | 4 (7.5%) |

| Fludarabine / Melphalan / Helical Tomotherapy | 1 (1.9%) |

| GVHD Prophylaxis | |

| FK-506 / Sirolimus | 45 (84.9%) |

| FK-506 / Sirolimus / MTX | 6 (11.3%) |

| FK-506 / Sirolimus / ATG | 1 (1.9%) |

| FK-506 / Sirolimus / MTX / ATG | 1 (1.9%) |

Patients received a conditioning regimen containing intravenous melphalan at a total dose of either 100 mg/m2 (n=6) or 140 mg/m2 (n=47) in combination with fludarabine 25 mg/m2 for 5 days for a total of 125 mg/m2 (n=49) or with clofarabine (CloMel: n=4) per an institutional protocol (NCT01885689). One patient received additional total marrow and lymph node irradiation (FluMel/TMLI) at 1200 cGy dose (NCT00800150). The choice of conditioning regimen was based on our institution standard of operation (SOP), treating physician’s choice, and enrollment in specified clinical trials.).

Engraftment outcomes

Of the 53 patients in this study, 52 achieved neutrophil engraftment with median of 15 days (range: 11–29), one patient died before engraftment on day 24 due to respiratory failure. Median time to platelet engraftment was 14 days (range: 12–243). Among the 50 patients tested for chimerism using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method, more than 95% achieved donor chimerism of >95% by 6 weeks, indicating the semi-myeloablative natural of this regimen.

Graft-versus-Host disease

The cumulative incidence of grades II to IV and III to IV acute GVHD at 100 days were 37.7% (95% CI: 24.8–50.6) and 18.9% (95% CI: 9.6–30.5), respectively. (Figure 1a) The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD was 54.7% (95% CI: 40.2–67.1) at 1 year and 61.9% (95% CI: 46.5–74.0) at 2 years after transplantation. (Figure 1b) The cumulative incidence of extensive chronic GVHD was 43.4% (95% CI: 29.7–56.3) at 1 year and 45.9% (95% CI: 31.7–58.9) at 2 years. (Figure 1b)

Figure 1.

Survival outcome

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years was 19.3% (95% CI: 9.8–31.1). (Figure 2a) The cumulative incidence of NRM was 9.4% (95% CI: 3.4–19.2) at 100 days and 17.0% (95% CI: 8.3–28.3) at 2 years. (Figure 2a) after the median follow-up of 31.1 months (range: 12.1–98.9), the probabilities of two-year mGRFS, PFS, and OS rates were 36.8% (95% CI: 23.8–49.8), 63.8% (95% CI: 49.2–75.2), and 68.9% (95% CI: 54.3–79.7), respectively. (Figure 2b) Disease relapse (n=8) and infection (n=7) were the most common causes of death in this cohort, 3 patients died of GVHD, and 2 of multi-organ failure. Cause of death was unknown in 3 patients.

Figure 2.

Psychosocial evaluation and disposition

All patients who are candidates for a transplant at our institution have to undergo a mandatory psychosocial evaluation conducted by a social worker. Based on this pre-transplant evaluation, 86.8% of patients were considered to have an adequate care plan (i.e., a designated primary and back-up caregiver), 77.4% had no substance use concerns, and around 81% were deemed to have appropriate financial stability and social support. At the time of discharge, 44 patients (83%) were discharged home and 5 patients (9.4%) needed to be discharged to a rehabilitation facility. Median duration of hospital stay was 33 days (range=20–147) and 14 (26.4%) patients were readmitted to the hospital within the first 6 months of post-transplant.

Early complications post-HCT

Intensive care unit (ICU) transfer was required for 13 patients (24.5%) during their hospitalization with median ICU stay duration of 7 days (range: 1–48). Also during their hospital stay, 25% of patients required a CT scan of the brain for various reasons including: fall (n=3), confusion (n=5), change in mental status (n=3), headache (n=1), and infection (n=1). During the first 100 days, 16 patients (30%) had tacrolimus discontinued due to: nephrotoxicity (n=7), neurotoxicity (n=2), or thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) (n=3) or other causes (n=4). Notably, 6 of these 16 patients who had to stop tacrolimus developed grade II-IV acute GVHD with no significant difference in outcome when compared to others (data no shown). In the first 100 days post-HCT, eleven patients (20.7%) had 12 blood-stream infections (BSI) with a median time to onset of 23.5 days (range: 0–92 days). Detailed description of post-transplant infections are presented in the supplement material.

Clinical variables and transplant outcomes

In univariate analyses, DRI was significantly associated with OS. None of the other variables evaluated was significantly associated with OS in this cohort (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analyses of OS

| Predictor | Group | N | 1 Yr (95%CI) | 2 Yr (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | Log- rank test p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at HSCT, years | 70 | 19 | 0.842(0.587,0.946) | 0.730(0.467,0.878) | Reference | 0.16 |

| 71 | 14 | 0.571(0.284,0.780) | 0.500(0.229,0.722) | 2.51(0.93,6.76) | ||

| ≥72 | 20 | 0.800(0.551,0.920) | 0.800(0.551,0.920) | 1.41(0.48,4.10) | ||

| Sex | Male | 35 | 0.743(0.564,0.857) | 0.643(0.456,0.780) | Reference | 0.15 |

| Female | 18 | 0.778(0.511,0.910) | 0.778(0.511,0.910) | 0.53(0.20,1.41) | ||

| HLA Matched Related Donor | Yes | 11 | 0.909(0.508,0.987) | 0.909(0.508,0.987) | Reference | 0.18 |

| No | 42 | 0.714(0.552,0.826) | 0.631(0.462,0.759) | 2.01(0.67,6.01) | ||

| Female donor to male recipient | Yes | 12 | 0.667(0.337,0.860) | 0.583(0.270,0.801) | Reference | 0.58 |

| No | 41 | 0.780(0.621,0.879) | 0.723(0.554,0.836) | 0.77(0.30,1.97) | ||

| ABO compatibility | Yes | 25 | 0.840(0.628,0.937) | 0.793(0.571,0.909) | Reference | 0.13 |

| No | 28 | 0.679(0.473,0.818) | 0.596(0.388,0.753) | 1.91(0.81,4.52) | ||

| DRI score§ | Low- intermediate High-very high | 34 | 0.824(0.649,0.917) | 0.752(0.562,0.868) | Reference | 0.004 |

| 19 | 0.632(0.379,0.804) | 0.574(0.325,0.760) | 3.21(1.39,7.43) | |||

| HCT comorbidity index | 0 | 20 | 0.800(0.551,0.920) | 0.686(0.428,0.846) | Reference | 0.91 |

| 1–2 | 10 | 0.600(0.253,0.827) | 0.600(0.253,0.827) | 1.25(0.42,3.74) | ||

| 3 | 21 | 0.810(0.569,0.924) | 0.756(0.508,0.891) | 1.01(0.37,2.81) | ||

| Recipient/Don or CMV serostatus | Negative/Negative | 12 | 0.667(0.337,0.860) | 0.667(0.337,0.860) | Reference | 0.62 |

| Any positive | 41 | 0.780(0.621,0.879) | 0.692(0.520,0.813) | 1.31(0.44,3.87) | ||

| Karnofsky performance status % | 90–100 | 35 | 0.771(0.595,0.879) | 0.707(0.523,0.831) | Reference | 0.57 |

| 70–80 | 17 | 0.706(0.431,0.866) | 0.635(0.359,0.818) | 1.29(0.52,3.23) |

Pre-HCT muscle mass

Among the 26 patients with available pre-HCT CT scans, 9 (34.6%) had abnormal muscle mass. There was no difference in Karnofsky performance status (88.9% vs 64.7% scored 90–100, p=0.36), NRM (22.2% vs. 17.6%, p=0.71), or OS (66.7% vs. 69.7%, p=0.48) between patients with low pre-HCT muscle mass and those with normal muscle mass.

DISCUSSION

Due to higher rates of transplant-related morbidity and mortality in older adults, alloHCT was not historically offered for this population. Fortunately, with emerging encouraging results due to advances in supportive care, donor selection strategies, and conditioning and GVHD prophylactic regimens, HCT is now increasingly offered for adults aged 70 and over. A recent CIBMTR analysis reports almost 40% of their elderly patients (≥70 years) were alive at 2 years post alloHCT, with relapse being the primary cause of death in this population, similar to younger patients. Our study adds to the literature, by reporting favorable survival outcomes in a case series of 53 patients in their eighth decade of life, treated at a single institution. The majority of patients in our study were male, with AML or MDS, with a smattering of other indications, very similar to other studies reported previously by other groups.5,6 As one would expect, in this population, the majority of transplants were from unrelated donors, most probably due to the lack of a suitable sibling donor, or the choice of the treating physician to use a younger unrelated donor on account of the age of the matched sibling.12,13,27

In our cohort, all but one patient achieved neutrophil engraftment at a median of 15 days, with more than 95% of patients achieving complete donor chimerism within 6 weeks post-transplantation based on blood or bone marrow chimerism analysis, consistent with the semi-ablative nature of melphalan-based reduced intensity conditioning.8,9,11,28 This conditioning intensity and rapid donor engraftment led to a favorable OS, PFS, and low relapse rate in our cohort compared with previously reported results.5,6 In a report by Brunner et al, the 2 year OS and PFS were both at 39%, and the 2 year relapse rate and NRM were at 56% and 5.6%, respectively. In contrast, in our study, at a median follow-up of 31.1 months, we are reporting the 2-year OS and PFS of 68.9% and 63.8%, respectively; where the 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse was only 19.3%. The encouraging PFS, and lower rate of relapse in our study as compared to other studies in a similar age population6 came with a higher albeit acceptable rate of NRM and GVHD. Chronic GvHD is known to be the leading cause of NRM in transplant patients surviving more than 2 years after HCT.29–31 Given the higher burden of chronic GvHD on older patient’s quality of life (QOL), as compared to younger patients, and the increasing number of older patients undergoing alloHCT, further studies exploring the impact of extensive GvHD on older patients QOL is clearly warranted. However, our current data suggest that the risk-benefit ratio justifies FluMel-based RIC HCT in selected patients in their eighth decade of life, and can be more favorable than truly non-myeloablative HCTs.

While the survival outcomes were generally favorable, hospitalization was complicated by ICU transfers, and altered mental status or fall requiring brain imaging in a quarter of patients. These outcomes are required to be further explored in future studies since delirium is a known neuropsychiatric complication in the management of cancer patients, and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and length of hospitalization.32–35 Age-related cognitive decline may increase the risk of delirium,36 which itself has been linked with higher risk of long-term cognitive impairment including dementia.37 Furthermore, administration of calcineurin inhibitor (i.e. Tacrolimus) with neurotoxic effects, could be detrimental especially in this age group. In our cohort, observation of neurotoxicity in 2 (4%) of patients led to drug intolerance and discontinuation, but overall stopping of tacrolimus elicited grade II-IV GVHD in some of these patients, but did not lead to worse outcome.

Infection is one of the major complications of alloHCT. In our cohort, infection rates were comparable and in fact much lower than those reported in the literature (although, age distribution is not defined as elderly in these studies).14 In a matched case control study comparing bacterial and fungal infection incidence and outcomes following nonmyeloablative versus myeloablative HCT, rate of bacteremia and invasive aspergillosis in the first 100 days post transplantation were 27% and 15%, respectively.14 Frere et al, reported an even higher incidence of bacteremia (33.8%) and IFI (8%) during the first 100 days after HCT.15 These rates are much higher than infection rates in our cohort, presented in this study. The CMV reactivation rates in our cohort were also lower when compared to that reported in the literature.16 Our results suggest that the alloHCT approach described herein is accompanied by less complications compared to the reported literature for infectious disease outcomes. However, our study was limited by difficulties in detailed infection data collection at time-points later than 100 days post-HCT.

Chronologic age alone has not been clearly shown to be an independent poor prognostic indicator of alloHCT outcomes. A comprehensive geriatric assessment including evaluation of patient’s medical, psychosocial and functional capabilities is required to provide a more accurate assessment of the patient’s ability to go through such an invasive treatment. Such assessment could be utilized to identify areas of vulnerability and to develop a coordinated and integrated treatment plan for alloHCT and long-term follow-up.20,38–41 In the absence of such in person assessments, radiographic approaches such as muscle mass assessment may shed light on biologic age and functional reserve. In patients with solid cancers (e.g. colorectal, lung, breast), low muscle mass has been associated with higher NRM and OS, independent of age. In the current study, there was no difference in NRM or OS by pre-HCT muscle mass. Due to the small numbers of patients with pre-HCT CT scans we are not able to speculate on the association between transplant outcomes and low muscle mass in our cohort. Additional studies are needed to examine the prognostic utility of pre-HCT imaging in combination with functional measures of physiologic reserves on post-HCT outcomes in this older population.

Our study carries inherited limitation of small, retrospective and single-center trials. However, this study describes a uniformly and recently treated cohort and reflects the real outcome of our current practice for elderly patients, and hints to the fact that result of this cohort of older population are similar and in accordance with results from younger cohorts with patients that are carefully selected.

In conclusion, our study using melphalan based semi-ablative conditioning demonstrates acceptable toxicities, lower risk of relapse, and a favorable overall survival in selected patients in their eighth decade of life. This approach is arguably one of the most effective available treatments, and should be considered for eligible older individuals with hematologic malignancies. Longer follow-up is needed in larger multicenter studies with incorporation of geriatric assessments to determine which patients are likely to benefit the most from alloHCT, and which patients are at the highest risk of NRM, and to include interventions to abrogate these risks.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Semi-ablative melphalan-based conditioning regimen is safe for eligible elderly patients.

Rapid hematopoietic reconstitution after this regimen led to favorable survival outcomes.

Morbidity indicators (infection, etc.) were similar to younger patients undergoing same regimen.

This regimen is effective with promising relapse rate and minimal toxicities for patients >70.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pulte D, Jansen L, Castro FA, Brenner H. Changes in the survival of older patients with hematologic malignancies in the early 21st century. Cancer. 2016;122(13):2031–2040. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Incidence of haematological malignancy by subtype: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(11):1684–1692. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oran B, Weisdorf DJ. Survival for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a population-based study. Haematologica. 2012;97(12):1916–1924. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.066100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma X, Does M, Raza A, Mayne ST. Myelodysplastic syndromes: incidence and survival in the United States. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1536–1542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muffly L, Pasquini MC, Martens M, et al. Increasing use of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients aged 70 years and older in the United States. Blood. 2017;130(9):1156–1164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-772368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunner AM, Kim HT, Coughlin E, et al. Outcomes in patients age 70 or older undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(9):1374–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez R, Nademanee A, Ruel N, et al. Comparison of reduced-intensity and conventional myeloablative regimens for allogeneic transplantation in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(12):1326–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura R, Palmer JM, O'Donnell MR, et al. Reduced intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for MDS using tacrolimus/sirolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis. Leuk Res. 2012;36(9):1152–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura R, Rodriguez R, Palmer J, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with fludarabine and melphalan is associated with durable disease control in myelodysplastic syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40(9):843–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delioukina M, Zain J, Palmer JM, Tsai N, Thomas S, Forman S. Reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation using fludarabine-melphalan conditioning for treatment of mature T-cell lymphomas. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(1):65–72. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein AS, Palmer JM, O'Donnell MR, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning followed by peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for adult patients with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(11):1407–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroger N, Zabelina T, de Wreede L, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for older advanced MDS patients: improved survival with young unrelated donor in comparison with HLA-identical siblings. Leukemia. 2013;27(3):604–609. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robin M, Porcher R, Ades L, et al. Matched unrelated or matched sibling donors result in comparable outcomes after non-myeloablative HSCT in patients with AML or MDS. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(10):1296–1301. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junghanss C, Marr KA, Carter RA, et al. Incidence and outcome of bacterial and fungal infections following nonmyeloablative compared with myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a matched control study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8(9):512–520. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12374456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frere P, Baron F, Bonnet C, et al. Infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37(4):411–418. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teira P, Battiwalla M, Ramanathan M, et al. Early cytomegalovirus reactivation remains associated with increased transplant-related mortality in the current era: a CIBMTR analysis. Blood. 2016;127(20):2427–2438. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-679639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baron F, Labopin M, Peniket A, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning with fludarabine and busulfan versus fludarabine and melphalan for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121(7):1048–1055. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunner AM, Kim HT, Coughlin E, et al. Outcomes in Patients Age 70 or Older Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancies. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2013;19(9):1374–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106(8):2912–2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solh M, Zhang X, Connor K, et al. Donor Type and Disease Risk Predict the Success of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Single-Center Analysis of 613 Adult Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Recipients Using a Modified Composite Endpoint. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(12):2192–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69(2):204–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(12):1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S, Ruijgrok C, Ostelo RW, et al. The assessment of anorexia in patients with cancer: cut-off values for the FAACT-A/CS and the VAS for appetite. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(2):661–666. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2826-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S, Versteeg KS, de van der Schueren MA, et al. Loss of Muscle Mass During Chemotherapy Is Predictive for Poor Survival of Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1339–1344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.6043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):412–423. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, et al. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(12):1539–1547. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruggeri A, Battipaglia G, Labopin M, et al. Unrelated donor versus matched sibling donor in adults with acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse: an ALWP-EBMT study. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13045-016-0321-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder DS, Palmer J, Stein AS, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation following reduced intensity conditioning for treatment of myelofibrosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(11):1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duell T, van Lint MT, Ljungman P, et al. Health and functional status of long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation. EBMT Working Party on Late Effects and EULEP Study Group on Late Effects. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(3):184–192. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-3-199702010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Socie G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Late Effects Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(1):14–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Jawahri A, Pidala J, Inamoto Y, et al. Impact of age on quality of life, functional status, and survival in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(9):1341–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solomon SR, Sizemore C, Zhang X, et al. Current Graft-versus-Host Disease-Free, Relapse-Free Survival: A Dynamic Endpoint to Better Define Efficacy after Allogenic Transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(7):1208–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khoury HJ, Wang T, Hemmer MT, et al. Improved survival after acute graft-versus-host disease diagnosis in the modern era. Haematologica. 2017;102(5):958–966. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.156356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerds AT, Woo Ahn K, Hu ZH, et al. Outcomes after Umbilical Cord Blood Transplantation for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(6):971–979. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solomon SR, Sizemore CA, Zhang X, et al. Impact of Donor Type on Outcome after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Acute Leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(10):1816–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorgeis J, Zhang X, Connor K, et al. T Cell-Replete HLA Haploidentical Donor Transplantation with Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide Is an Effective Salvage for Patients Relapsing after an HLA-Matched Related or Matched Unrelated Donor Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(10):1861–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solh M, Zhang X, Connor K, et al. Factors Predicting Graft-versus-Host Disease-Free, Relapse-Free Survival after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Multivariable Analysis from a Single Center. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(8):1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solomon SR, Aubrey MA, Zhang X, et al. Selecting the Best Donor for Haploidentical Transplant: Impact of HLA, KIR Genotyping, and Other Clinical Variables. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solh MM, Bashey A, Solomon SR, et al. Long term survival among patients who are disease free at 1-year post allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a single center analysis of 389 consecutive patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41409-017-0076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casulo C, Friedberg JW, Ahn KW, et al. Autologous Transplantation in Follicular Lymphoma with Early Therapy Failure: A National LymphoCare Study and Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.12.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bashey A, Zhang MJ, McCurdy SR, et al. Mobilized Peripheral Blood Stem Cells Versus Unstimulated Bone Marrow As a Graft Source for T-Cell-Replete Haploidentical Donor Transplantation Using Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(26):3002–3009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.8428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.