Abstract

The developmental timing of suicide-related disparities between heterosexuals and sexual minorities (i.e., lesbian/gay and bisexual (LGB) people) is an understudied area that has critical prevention implications. In addition to developmentally situated experiences that shape risk for suicidality in the general population, sexual minorities also experience unique social stressors (e.g., anti-LGB stigma) that may alter their risk for suicidal behavior at different ages. Using a nationally representative US sample of adults, we assessed age-varying rates of suicidal behavior among heterosexuals and sexual minorities ages 18 to 60 and the age-varying association between anti-LGB discrimination and suicidal behavior. We also tested whether these age-varying prevalences and associations differed for men and women and for sexual minorities who did and did not endorse a sexual minority identity. Results indicate a critical period for suicide behavior risk for sexual minorities during young adulthood, with the highest rates of risk at age 18 followed by a steady decline until the early 40s. Disparities were particularly robust for sexual minorities who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual. This pattern was present for both men and women, though sexual minority women in their 30s were more likely to report suicidal behavior than heterosexuals and sexual minority men. Sexual minorities who experienced anti-LGB discrimination were more likely to report suicidal behavior, but the significance of this association was limited to those under 30. The effect of discrimination on suicidal behavior was stronger among young adult sexual minority men, relative to sexual minority women, but was present for a wider age range for sexual minority women (until age 30) relative to sexual minority men (until age 25).

Keywords: LGB, Sexual minority, suicidal behavior, suicidality, young adulthood, lifespan, time-varying effect modeling

Introduction

A robust body of literature documents disparities in suicide risk for sexual minorities (i.e., lesbian/gay, bisexual (LGB)) compared to heterosexuals (Haas et al. 2010; Institute of Medicine 2011; King 2008; Marshal et al. 2011; Plöderl and Tremblay 2015; Russell and Joyner 2001). Results from meta-analytic studies suggest that LGB adults are nearly 2.5 times (King 2008) and LGB youth 3 times (Marshal et al. 2011) as likely as heterosexuals to report suicide attempts. With rates of suicide on the rise (Curtin et al. 2016), public health efforts have now turned towards understanding the mechanisms (e.g., stigma, discrimination) that drive risk for suicidal behavior among LGB people and within-group differences (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity) that may inform focused prevention efforts (Institute of Medicine 2011; US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) 2012).

Research indicates a developmental trend in risk for suicidal behavior (e.g., suicide attempts) in the general population with adolescents and young adults displaying the highest reported risk for suicide attempts compared to other age groups, particularly among females (Nock et al. 2008, 2013). Adolescence and the transition to adulthood is a time of rapid individuation which includes an escalation of responsibilities in education, career planning and engagement, financial autonomy, and self-reliance—all while managing changing social relationships with parents and increasingly more intimate relationships with friends and romantic partners (Collins and Steinberg 2006). This time is also a critical period for several anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders which indicate onset during this developmental transition (Kessler et al. 2005; Nock et al. 2008). As these stressors and vulnerabilities converge, it is not surprising that suicidal behavior peaks during adolescence and the transition to adulthood.

The developmental tasks of adolescence and young adulthood are often compounded for sexual minorities due to experiences of anti-LGB stigma, discrimination, victimization, and (potentially) strained and rejecting family, peer, and other social relationships (Russell and Fish 2016). Thus, understanding the developmental timing of sexual orientation disparities in suicide-related behaviors has critical prevention and intervention implications (Haas et al. 2010; Russell and Toomey 2012), though a surprisingly limited number of studies have done so (D’Augelli et al. 2001; Fergusson et al. 2005; Russell and Toomey 2012). In a survey of older adults, for example, D’Augelli et al. (2001) found that retrospective reports of suicidal behavior varied by age: For those with lifetime suicidal behavior, 27% stated that they had attempted suicide before age 21, 69% between ages 22 and 59, and 4% after the age of 60. Using a population-based, longitudinal birth cohort study of New Zealanders, Fergusson et al. (2005) noted that gay and bisexual men reported a 28% increase, and lesbian and bisexual women a 10% increase, in lifetime suicidal behavior from 21 to 25, relative to 1.6 and 1.5% of heterosexual men and women, respectively. To date, the most comprehensive investigation of the developmental timing of suicidal behavior among sexual minority (SM) youth and young adults was conducted using data from four waves of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Russell and Toomey 2012). The findings revealed adolescence (ages 12–19) as a critical period for SM disparities in suicidal behavior relative to the 20s and early 30s, when heterosexual and SM men and women did not statistically differ in their rates of suicidal behavior.

Although men are more likely to die by suicide than women (Curtin et al. 2016), women consistently indicate higher rates of nonlethal suicidal behavior than men (Nock et al. 2013), particularly during adolescence and young adulthood (Nock et al. 2008). Gender differences in self-reported suicidal behavior among SMs, however, show mixed findings. In a meta-analysis of SM youth and adults, King et al. (2008) found that gay and bisexual men were four times as likely as heterosexual men to report lifetime suicidal behavior, whereas lesbian and bisexual women were nearly two times as likely as heterosexual women to indicate lifetime suicidal behavior. Marshal et al. (2011), however, found no sex differences in SM disparities of suicidal ideation, behavior, or medical severity in their meta-analytic review of youth-specific studies. In a more recent systematic review, Plöderl and Tremblay (2015) concluded that the majority of studies testing SM disparities in suicidal behavior document larger effects for men than women—though a number of studies reviewed reported similar effects.

Anti-LGB Discrimination and Suicidal Behavior

Minority stress theory (Meyer 2003), a leading explanatory model for sexual orientation-related health disparities, posits that unique and chronic stressors related to stigma increase vulnerability for a host of mental, behavioral, and physical health problems, including suicidal behavior. Indeed, the literature supports that SM youth and adults who experience discrimination and victimization indicate worse health outcomes (Goldbach et al. 2014; Lick et al. 2013; Russell and Fish 2016) and SMs across age groups typically report more frequent and severe instances of harassment than heterosexuals (Kann et al. 2016; Toomey and Russell 2013; Katz-Wise and Hyde 2012). A recent nationally representative school-based study found that 34% of LGB youth experienced bullying on school property relative to 19% of heterosexual students (Kann et al. 2016). Similarly, 50% of gay men and 54% of lesbian women in a recent sample of US adults reported experiences with anti-LGB discrimination in the past year (Bostwick et al. 2014).

Studies also illuminate the distinct impact of biased-based, relative to general, harassment. That is, experiences of discrimination are more strongly associated with poor health outcomes than general harassment (Poteat et al. 2011; Poteat and Russell 2013; Russell et al. 2012). Youth who experience nonbias-based harassment, for example, had 2.5 times the odds of suicidal behavior, whereas those reporting LGB-based harassment were over 5.5 times as likely to report suicidal behavior (Russell et al. 2012). To date, more studies document experiences of anti-LGB discrimination and victimization among youth than adults (c.f., Hatzenbuehler et al. 2009; McCabe et al. 2010) and few investigate the impact of these experiences during middle and late adulthood (ages 50+; IOM2011; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2013).

SM boys and men consistently report more harassment and greater family rejection than SM girls and women (Katz-Wise and Hyde 2012; Ryan et al. 2009; Toomey and Russell 2013). Experiences with victimization and bullying generally diminish as youth age past middle school, but these declines are less pronounced for SM, relative to heterosexual youth and particularly for SM boys (Robinson et al. 2013). In fact, gay and bisexual boys indicate an increase in the experience of victimization after the age of 17, which leaves them vulnerable to the effects of victimization for longer periods of time. Importantly, these experiences have long-term consequences: Young adults who experienced anti-LGB victimization during adolescence report lower levels of life satisfaction and higher levels of depression in their early 20s (Toomey et al. 2010; Russell et al. 2014).

Only one study, to the authors’ knowledge, tracks developmental trends in the experience of anti-LGB discrimination and victimization in adulthood (ages 18–60+) (Fish et al. 2017a, b). Findings indicate that rates of general discrimination (i.e., in stores, restaurants, or on the street) and victimization (i.e., being called names, pushed, hit, or threatened) were highest among SM young adults ages 18 to 30. Similar to previous research (Katz-Wise and Hyde 2012), SM men were more likely to report more severe forms of harassment (i.e., victimization), though this sex difference was specific to young adults.

The Current Study

Despite knowledge on developmental differences in suicidal behavior and experiences with discrimination, there is limited understanding of how the association between discrimination and suicidal behavior varies over the lifespan. Building on findings from Russell and Toomey (2012), we used a nationally representative sample of US adults ages 18 to 60 to assess developmental differences in disparities of suicidal behavior between heterosexual and SM adults. We also extend these findings by examining the association between anti-LGB discrimination and suicidal behavior across development periods. Based on previous research, we also explored whether these age-varying prevalences and associations differed for men and women and whether SMs with an LGB identity indicated differential risk for recent suicidal behavior than those SMs who reported same-sex attraction or behavior, but did not adopt a sexual minority identity. Specifically, we used time-varying effect modeling (TVEM; Tan et al. 2012) to examine (1) age-varying prevalences of recent suicidal behavior between heterosexual and SM adults, (1a) differences in age-varying prevalences of recent suicidal behavior by sex and sexual identity, (2) age-varying associations between anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior among SM adults and (2a) differences in age-varying associations between anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior by sex.

Method

Data Source and Sample

Data are from the National Epidemiological Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) III, a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of noninstitutionalized civilian adults ages 18 and older collected in 2012–2013 (N = 36,309; Grant et al. 2014). Data were collected via computer-assisted personal interviews using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule 5 (AUDADIS-5), conducted by trained interviewers. The NESARC protocol was originally approved by the US Census Bureau and the US Office of Budget and Management. NESARC-III provides sampling weights, which we included in all analyses to generate nationally representative estimates.

Two analytic samples were created to address the study goals. First, a sample of adults ages 18 to 60 who provided a valid response to items assessing SM status and suicidal behavior (weighted n = 27,768.57) was created to examine sexual minority-related disparities in suicidal behavior; we refer to this as the full study sample. Second, because only SMs responded to questions about experiences with anti-LGB discrimination, we restricted our full study sample to adults age 18 to 60 who identified as SMs based on their reports of same-sex attraction, same-sex sexual partners, or a SM identity (i.e., lesbian/gay or bisexual) (weighted n = 2814.78). We refer to this subsample as the SM sample.

Measures

Sexual minority status

SM status was measured via three items: sexual attraction, sexual behavior, and sexual identity. First, sexual attraction was assessed with the question “People are different in their sexual attraction to other people. Which category on the card best describes your feelings?” Response options included “only attracted to females,” “mostly attracted to females,” “equally attracted to females and males,” “mostly attracted to males,” and “only attracted to males.” Using self-reported biological sex (male, female), participants were categorized as (exclusively) attracted to other-sex partners and any same-sex attraction. Lifetime sexual behavior was measured with the question “In your lifetime, have you had sex with only males, only females, both males and females, or have you never had sex?” Response options were “only males,” “only females,” “both males and females,” and “never had sex.” Responses were recoded to characterize lifetime sexual partners as exclusively other sex or never had sex and any same sex. Sexual identity was assessed with a single item asking participants “Which of the following best describes you?” Response options were “heterosexual (straight),” “gay or lesbian,” “bisexual,” and “not sure.” Participants who reported any same-sex attraction, any same-sex partners, or a lesbian/gay or bisexual identity were coded as sexual minorities. Adults reporting exclusive attractions to and behaviors with members of another sex and a heterosexual identity were coded as heterosexual. Those who reported their sexual identity as “not sure” were excluded from analyses if they did not also provide reports of attraction or lifetime sexual behavior.

Suicidal behavior

Lifetime suicidal behavior was assessed with the question, “Ever attempted suicide in your entire life”. A Byes” response was coded as (1) and a “no” or “unknown” response was coded as (0). To estimate suicidal behavior in the past 5 years (i.e., recent suicidal behavior), we subtracted participant responses to “age at most recent suicide attempt” from their current age. If the difference was 5 years or less, recent suicidal behavior was coded as (1) and if it was greater than 5 years or if they had never engaged in suicidal behavior, it was coded as (0). The mean difference between current age and the age at last attempt for the overall sample was 13.8 years (SD = 11.0).

Anti-LGB discrimination

The six-item Experiences of Discrimination scale (Krieger and Sidney 1997; Krieger et al. 2005) assessed participants’ lifetime experience with anti-LGB discrimination. Example items include, “how often did you experience discrimination in public, like on the street, in stores or in restaurants, because you were assumed to be gay, lesbian, or bisexual?” and “how often were you made fun of, picked on, shoved, hit, or threatened with harm because you were assumed be gay, lesbian, or bisexual,” with response options ranging from never (0) to very often (5). Items were coded to reflect participants who reported any anti-LGB discrimination in their lifetime (1) versus none (0).

Analytic Strategy

First, we calculated weighted frequencies of all variables to describe the full study sample. Second, we used weighted logistic regression to calculate the association between anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior among SM adults and, separately, by biological sex and for SMs who did and did not identify as LGB. Third, we used logistic time-varying effect modeling (TVEM; Dziak et al. 2017) to estimate age-varying prevalences of recent suicidal behavior and associations between anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior (see Lanza et al. 2016). With cross-sectional data, TVEM facilitates the identification of precise age ranges during which certain characteristics are associated with heightened risk for an outcome (Russell et al. 2016). To better elucidate developmental periods of risk, we conducted intercept-only models by estimating the overall age-varying prevalences of lifetime suicidal behavior and compared that to a model that estimated rates in the last 5 years. We then estimated the sex-specific age-varying prevalences of recent suicidal behavior, as well as for SMs who did and did not identify as LGB. Finally, to evaluate the association between discrimination and suicidal behavior, we estimated the age-varying associations between lifetime anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior, first among the overall SM sample and then separately for SM men and women. Given the power required for TVEM, we were unable to estimate age-varying associations between anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior across different measures of sexual minority status (i.e., SMs with and without an LGB identity). Results are presented as figures to better illustrate the regression coefficients as a function of age. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 using the %TVEMmacro (WeightedTVEM SAS Macro 2017; Dziak et al. 2017).

Results

Characteristics of the SM Sample

Just over 10% of the population of adults was categorized as SMs using our inclusive definition that captured same-sex attraction, same-sex behavior, and lesbian/gay or bisexual identity. Among SMs, 39% were male and the median age was 36. The SM sample was racially diverse (63% White, 13%Black, 16%Hispanic, 8% other). The median age among the heterosexual sample was 39 and 50% were male. Among heterosexual adults, 62% were White, 13% Black, and 17% Hispanic. Compared to 5% of heterosexuals, 14% of SMs reported lifetime suicidal behavior. Recent suicidal behavior was reported by 1% of heterosexuals and 5% of SMs. Among the SM sample, 23% reported ever experiencing anti-LGB discrimination.

Prevalence of Suicidal Behavior throughout Adulthood by SM Status

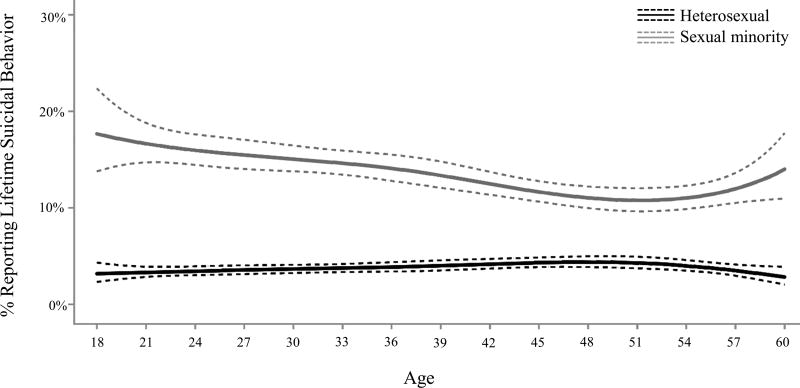

Age-varying prevalences for lifetime and past 5-year suicidal behavior are presented in Figure 1a, b, respectively. Lifetime reports of suicidal behavior among heterosexual and SM adults remain relatively stable across adulthood. Prevalence of lifetime suicidal behavior among SMs varied between 12 and 18% across ages 18 to 60. The disparity between heterosexual and SM adults with respect to lifetime suicidal behavior narrowed among middle-aged adults (ages 45–55), but remained statistically significant across all ages.

Figure 1.

Estimated age-varying prevalence of lifetime (a) and recent (b) suicidal behavior among heterosexual and sexual minority adults ages 18 to 60

Prior to modeling recent suicidal behavior by age, the overall association between SM status and recent suicidal behavior revealed an overall significant association (odds ratio (OR) = 4.24, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 3.48–5.16), whereby SM adults were more than four times as likely as heterosexual adults to report recent suicidal behavior. TVEM models, however, indicated that the prevalence of recent suicidal behavior varied considerably by age. Specifically, differences between heterosexual and SM adults were largest at age 18, when nearly 20% of SMs reported suicidal behavior in the last 5 years, compared to less than 5% of heterosexuals. The proportion of SMs reporting recent suicidal behavior decreased with age by more than half throughout young adulthood, with the disparity between SMs and heterosexuals continuing to narrow until the difference was not significant at age 50. Given that findings indicate an age-graded trend in recent suicidal behavior, we focused our examination of sex and sexual identity differences in trends and associations on this more proximal outcome.

Sex and Sexual Identity Differences in the Association between Sexual Minority Status and Suicidal Behavior

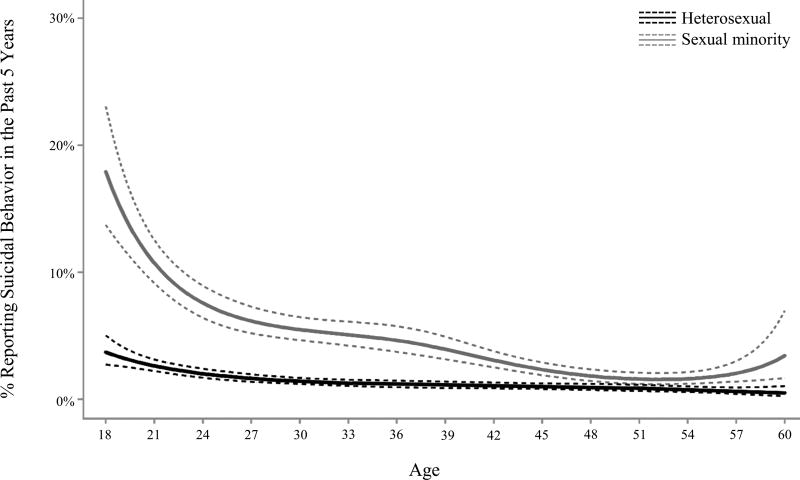

The age-varying differences in the prevalence of recent suicidal behavior comparing heterosexual and SM adults varied by sex (Figure 2). In general, SM women reported the highest rate of suicidal behavior, followed by SM men, heterosexual women, and heterosexual men, in that order. SM women were significantly more likely to report suicidal behavior compared to both heterosexual men and heterosexual women across all ages. Comparatively, disparities in recent suicidal behavior between heterosexual and SM men were significant from 18 until the late 40s. Differences across SM status were substantially stronger than differences across sex. Specifically, SM women were statistically more likely to report recent suicidal behavior than SM men only between the ages of 30 and 42. Notably, the same age range (ages 30–42) was the only period during which heterosexual women were significantly more likely than heterosexual men to report recent suicidal behavior.

Figure 2.

Estimated age-varying prevalence of recent suicidal behavior among heterosexual and sexual minority adults ages 18 to 60, by sex

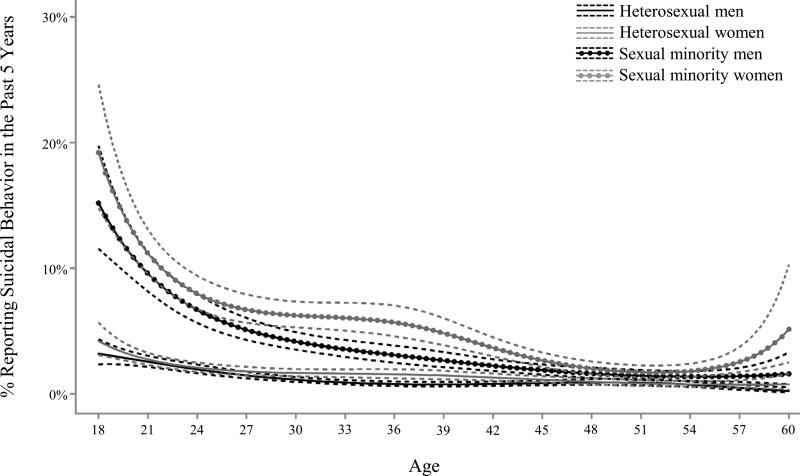

Age-varying disparities in recent suicidal behavior also differed between heterosexual and SMs on the basis of sexual identity (Figure 3). The age-graded trends in suicidal behavior disparities evidenced in Figure 1 were largely driven by SM adults who reported an LGB identity.

Figure 3.

Estimated age-varying prevalence of recent suicidal behavior among heterosexual, sexual minorities who identify as LGB, and sexual minorities who do not identify as LGB adults ages 18 to 60

Compared to heterosexuals and SMs who were not LGB, SMs who indicated on LGB identity were at greatest risk for suicidal behavior at age 18 with a precipitous decline across ages, where heterosexual and LGB SMs did not statistically differ on rates of suicidal behavior at age 52. Non-LGB SM adults between the ages of 18 to 21 did not statistically differ from heterosexuals, nor did non-LGB SM adults over the age of 47. LGB and non-LGB SMs also statistically differed in rates of suicidal behavior, where LGB SMs between the ages of 18 and 38 indicated higher rates of recent suicide attempts than non-LGB SMs.

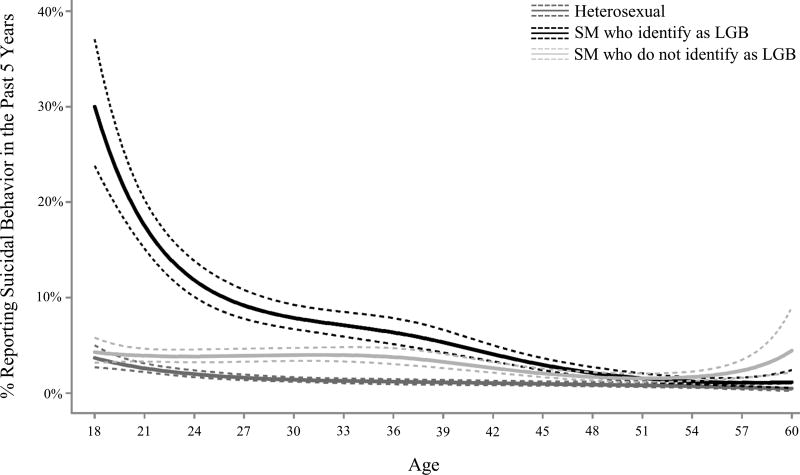

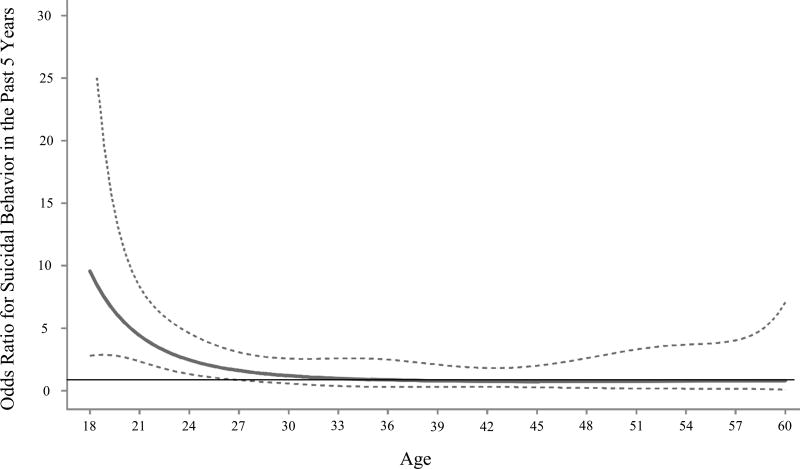

Association between Lifetime Discrimination and Recent Suicidal Behavior

Overall, SMs who reported ever experiencing anti-LGB discrimination were more than twice as likely to report recent suicidal behavior (OR = 2.26, 95% CI = 1.61–3.18). TVEM models, however, indicated differences by age. The association between anti-LGB discrimination and past 5-year suicidal behavior was strongest among SMs at age 18 (OR ≈ 10.00), with decreasing, but still significant, odds ratios through age 26. Among those between the ages of 27 and 60; however, there was no significant association between lifetime anti-LGB discrimination and past 5-year suicidal behavior (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Estimated age-varying odds ratio reflecting change in odds of recent suicidal behavior as a function of lifetime reports of anti-LGB discrimination among sexual minority adults ages 18 to 60. Traditional OR = 2.26, 95%CI = 1.61– 3.18). Ages at which 95%confidence interval does not include the value of OR = 1.00 (shown as horizontal line) indicate a statistically significant association

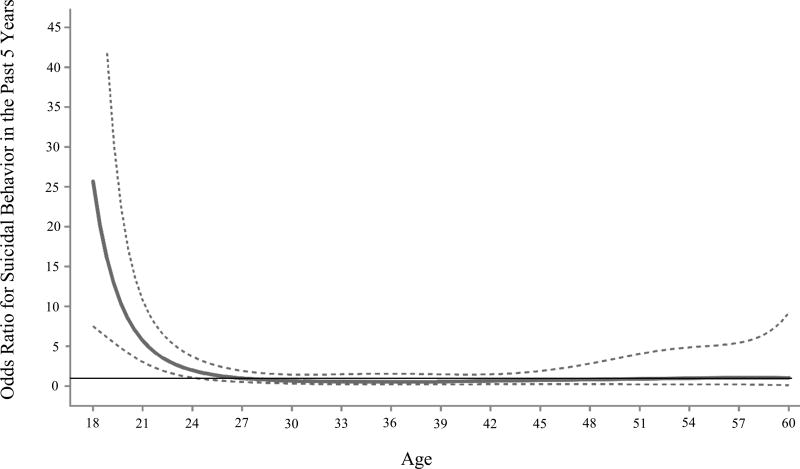

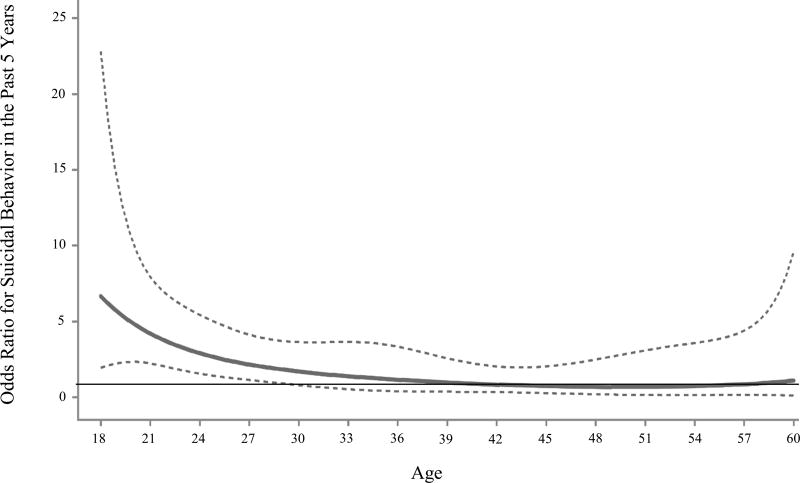

Sex Differences in the Association between Discrimination and Suicidal Behavior

Traditional logistic regression analyses revealed a significant association between lifetime experiences of anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior for both SM men (OR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.09–3.68) and women (OR = 2.71, 95% CI = 1.79–4.09). TVEM analyses, stratified by sex, indicated that these relationships also varied by age for both SM men and women. The pattern of age-varying associations between anti-LGB discrimination and suicidal behavior—characterized by the largest effect at age 18, followed by a decrease in the strength of this association during young adulthood— was generally similar for both men and women. However, the association between anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior was substantially stronger for young SM men (age 18 OR = 25.68, 95% CI = 7.52–87.69) (Figure 5) than it was for young SM women (age 18 OR = 6.67, 95% CI = 1.95–22.78) (Figure 6). Further, SM men and women differed in terms of the age after which the association was not statistically significant. Among SM men, the association between anti-LGB discrimination and suicidal behavior was statistically significant between ages 18 to 24; among SM women, the association was significant from ages 18 to 29.

Figure 5.

Age-varying odds ratio estimating recent suicidal behavior and lifetime reports of anti-LGB discrimination among sexual minority men. Traditional OR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.09–3.68). Ages at which 95% confidence interval does not include the value of OR = 1.00 (shown as horizontal line) indicate a statistically significant association

Figure 6.

Age-varying odds ratio estimating recent suicidal behavior and lifetime reports of anti-LGB discrimination among sexual minority women. Traditional OR = 2.71, 95% CI (1.79–4.09). Ages at which 95% confidence interval does not include the value of OR = 1.00 (shown as horizontal line) indicate a statistically significant association

Discussion

Previous research has established disparities in suicidal behavior between heterosexuals and SMs (King et al. 2008; Marshal et al. 2011; Plöderl and Tremblay 2015). This study extends these findings by examining how SM disparities in suicidal behavior change across the adult lifespan using TVEM and age-specific prevalence rates of suicidal behavior by sex and LGB identity. We also move this literature forward by modeling the age-varying association between anti-LGB discrimination and suicidal behavior among SM adults from ages 18 to 60. Findings demonstrate the need for focused programs that reach those within high-risk age ranges for suicidal behavior and policies that protect LGB people from discrimination, particularly during adolescence and young adulthood. Though not a direct aim of our study, we also demonstrate the utility of TVEM to illuminate critical developmental periods for minority health disparities with cross-sectional data, findings that inform focused and appropriately timed prevention and intervention strategies.

Sexual Minority Disparities by Age

Population health estimates indicate that 4.1% adolescents and 4.6% of adults report lifetime suicidal behaviors (Nock et al. 2013; Nock and Kessler 2006). In our examination, we note an approximately 10% lifetime rate of suicidal behaviors among SMs across the life course, with slightly lower prevalences among those 40 and older. Heterosexual adults reported a steady rate of lifetime suicidal behavior (~ 4%) with a slight increase in the 40s and 50s. Comparatively, findings demonstrated that SM disparities in recent suicidal behavior (i.e., in the last 5 years) varied by age. Specifically, results indicate a narrowing disparity between heterosexual and SM adults from age 18 (~ 14% difference) to 48 (~ 1% difference). Results support and extend conclusions drawn from previous studies that illuminate developmental differences in suicide risk (D’Augelli et al. 2001; Fergusson et al. 2005; Russell and Toomey 2012). Similar to previous research, we find that sexual orientation disparities in recent suicidal behavior are larger among young adults relative to older adults. Extending this work, we observed that this disparity sharply declines during the transition to adulthood and gradually narrows until age 50, where heterosexual and SM adults do not differ. In a notable departure from prior studies (Russell and Toomey 2012), our results suggest that disparities in suicidal behavior are not adolescent-limited but persist into early adulthood.

Due to previously inconclusive findings (King 2008; Marshal et al. 2011; Plöderl and Tremblay 2015), we hypothesized that developmental investigations could illuminate sex differences in suicidal behavior and disparities of suicidal behavior at different ages. Results indicate that SM disparities in suicidal behavior follow a similar trend for men and women from 18 to the early 40s, but that the magnitude of difference between heterosexual and SM men and women varied by age. SM men between the ages of 18 and 46 indicated disparities in recent suicidal behavior, whereas SM women up to the age of 60 were more likely to report recent suicidal behavior. Rates of recent suicidal behavior did not differ between SM men and women during young adulthood, but SM women in their 30s were more likely than same-aged SM men to report recent suicidal behavior. Results suggest that mixed findings regarding sex differences in sexual orientation risk for suicidal behavior could be related to the age distribution of samples.

Analyses testing differences in recent suicidal behavior across subgroups of SMs showed that disparities, when present, were particularly robust for SMs who identify as LGB. In fact, SMs who do not identify as LGB aged 18 to 21 did not differ in recent suicidal behavior from same-aged heterosexuals, though SMs who do not identify as LGB in their 20s, 30s, and early 40s did evidence disparities. Several studies document health differences across measures of sexual minority status (i.e., sexual attraction, behavior, and identity; Bostwick et al. 2010), though researchers rarely test differences in suicidality among sexual minorities on the basis of more than one measure at a time, as we do here (c.f. Fish and Pasley 2015). Our findings illustrate that such investigations may be warranted. Notably, modeling differences across SM subgroups demonstrated that our original estimates of recent suicidal behavior among SMs defined by attraction, behavior, and identity (in Figure 1b) underestimated risk for young adult SMs who identify as LGB and overestimated risk for SMs who do not identify as LGB. Approximately 18% of 18-year-old SMs, inclusive of attraction, behavior, and identity, indicated a recent suicide attempt compared to 30% of SMs who identify as LGB and 4% of SMs who do not identify as LGB of the same age. Findings suggest that identifying as LGB confers unique risk for suicidality beyond same-sex attraction and behavior. Minority stress theory (Meyer 2003) would lead us to hypothesize that identification with a stigmatized group may increase vulnerability for stigma, though more work is needed to better understand differences in risk for SM who do and do not identify as LGB. Future studies testing sexual orientation health disparities, including suicidality, may elucidate unique risk when considering more than one measure of sexual minority status.

Associations between Anti-LGB Discrimination and Suicidal Behavior by Age

Minority stress theory purports that disparities in suicidal behavior between heterosexuals and SMs are largely driven by experiences with anti-LGB stigma (e.g., discrimination, victimization; Meyer 2003). Our results support these findings. Lifetime reports of anti-LGB discrimination were significantly and strongly associated with recent suicidal behavior among SM adults, but this association was only significant for adults under the age of 40. That is, 18-year-old SMs, regardless of sex, indicated the strongest association between lifetime reports of anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior with a gradual decline in the strength of this association for ages up to 40. Preliminarily, results suggest that lifetime experiences with discrimination are more strongly related to suicidal behavior during the first few decades of life.

Why might this be? Adolescence is the period of development of awareness and understanding of one’s sexuality and sexual identity. It is also a period characterized by peer social regulation; in fact, discriminatory bullying, including homophobic bullying, is greatest in early adolescence (Poteat and Russell 2013; Robinson et al. 2013). The trends observed in these results beginning at age 18 follow the developmental period during which anti-LGB discrimination (bullying) appears to be most common in the life cycle. Thus, such discriminatory experiences are both more recent at younger ages, and more prevalent, and therefore may have greater influence on population-level mental health disparities. Alternatively, results may reflect developmental differences in self-acceptance or the acquisition of effective strategies to cope with discrimination, such as community support (Meyer 2015).

Though age-varying associations between anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior were similar for men and women, the strength and age range of this association differed. The positive association between lifetime reports of anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior was stronger for SM men (OR ≈ 26 vs. OR ≈ 7, for 18-year-old men and women, respectively), but was significant for a broader range of ages for SM women (women ages 18 to 30, men ages 18 to 26). Compared to SM women, SM men experience more frequent and severe forms of victimization and harassment (Fish et al. 2017a, b; Katz-Wise and Hyde 2012; Robinson et al. 2013); thus, the association between anti-LGB discrimination and suicidal behavior may be stronger due to these experiences. Regarding sex differences in the age range for which this association was significant, research indicates that SM women are more likely to report sexism than SM men (Bostwick et al. 2014). For those who hold multiple marginalized identities, experiences of discrimination for one identity are often seen as inherently linked to the prejudiced experiences related to the other (e.g., gendered-racism; Bowleg 2008; Lewis and Neville 2015). Anti-LGB discrimination, therefore, may also reflect sentiments of sexism and vice versa. As such, prolonged associations between anti-LGB discrimination and recent suicidal behavior may reflect experiences with compounded stressors related to sexism and anti-LGB stigma among SM women.

Another prominent contribution is the age-varying estimation of risk. The use of time-varying effect modeling provided a novel look at how risk for suicidal behavior changes across the lifespan. Estimates from traditional logistic regression indicated that adults who report lifetime experiences with anti-LGB discrimination had 2.25 times the odds of recent suicidal behavior compared to those who had not reported any anti-LGB discrimination. TVEM results, however, revealed that this statistic severely underestimated the risk for those in young adulthood (OR ≈ 10.00) and overestimated the risk for suicidal behavior for middle-aged and older adults (OR ≈ 1.00). Consequently, TVEM findings point to critical developmental periods for policy and program recommendations. The transition to adulthood, for example, is a time when experiences of discrimination are high (Fish et al. 2017a, b), and young adults are entering into institutions, such as jobs, universities, and the military; these institutions could improve the implementation of policies and anti-discrimination protections for LGB people in order to limit these experiences. Given that our measures capture lifetime experiences of anti-LGB stigma, findings also point to the importance of instituting policies, programs, and practices that eliminate anti-LGB discrimination for SM youth (e.g., in schools).

Notably, we observed a statistical difference in the rate of recent suicidal behavior among SM adults in their late 50s and early 60s, and this was largely due to increased prevalence among SM women. That is, SM women in their early 60s were more likely to report recent suicidal behavior than heterosexual men and women, though they did not differ from SM men. Findings indicate that older adulthood (60+), which has historically been seen as a time of high-risk for suicide among men (Curtin et al. 2016), may also be a time of risk for SM women. Given that experiences of anti-LGB discrimination are lower during older adulthood relative to early adulthood (Fish et al. 2017a, b), and associations between lifetime anti-LGB discrimination and suicidal behavior were not significant for these ages, there may be other factors at play that place older SM women at risk for suicidal behavior. Physical health and functioning, for example, are particularly salient risk factors for suicide in older adults (Conwell et al. 2011) and older SM women are more likely to report poor physical health and barriers to health care than SM men (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2013). Thus, it may be that basic physical health factors explain increased risk for recent suicidal behavior among SM women at these ages, though more work is needed in this area.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its strengths, there are a number of limitations of this study. First, the data reflect past 5-year reports of suicidal behavior, thus we were unable to pinpoint more precise age differences in suicidal behavior. Though we tested differences in the prevalence of lifetime and past 5-year rates of suicidal behavior to better elucidate developmental and cohort differences, the examination of past-year suicidal behavior would yield more precise estimates. Second, these data are restricted to adults (ages 18+). Therefore, we were unable to assess the prevalence of suicidal behavior or associations between anti-LGB discrimination and suicidal behavior for youth under age 18. Our measures capture reports of suicidal behavior in the past 5 years (which for those between the ages of 18 and 23 may include suicidal behavior in adolescence), but future studies should investigate trends from early adolescence (12+) through adulthood to better elucidate when critical periods for suicidal behavior emerge for SMs. Third, we did not assess whether disparities in suicidal behavior or the association between anti-LGB discrimination and suicidal behavior vary by other important demographic (i.e., race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status) and psychosocial risk factors (i.e., substance use disorder, mental health diagnosis). Intersectional experiences for LGB people of color (i.e., heterosexism and racism) may contribute to distinct differences in suicide risk by age. Fourth, we measured lifetime reports of discrimination as a binary variable (yes/no); however, there may be dosage effects whereby individuals who report more consistent experiences with anti-LGB discrimination may be more at risk for suicidal behavior. Future research should examine whether these differences in the measurement of anti-LGB discrimination provide additional information regarding risk for suicidality. Finally, the data are cross-sectional, therefore rates of suicidal behavior among SMs may reflect cohort effects that are not readily testable. There has been swift change in the social acceptance of LGB people in the United States and, thus, risk for suicidal behavior may vary for those born to different cohorts (Hammack et al. 2018; Phillips 2014). Studies that untangle these age, period, cohort effects for suicidal behavior, and other health disparities, would provide valuable insight into how shifting sociocultural attitudes are related to SM population health.

Conclusion

Studies that investigate age trends in suicide risk for SMs have been hampered by a lack of population-based survey data that include measures of both SM status as well as the age of reported suicidality (Haas et al. 2010; DHHS 2012). The relatively recent inclusion of measures of SM status and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in large, population-based studies are providing unique opportunities to not only study the prevalence of health-related disparities and their mechanisms but also whether these experiences vary across the lifespan, and for whom. Yet more recent efforts to eliminate measures of SM status in federal health surveys threaten the nation’s public health research and program infrastructure (Cahill and Makadon 2017).

Whereas earlier studies have identified adolescence as a critical period for SM suicidality (e.g., Russell and Toomey 2012), our results show that the period of vulnerability for suicidal behaviors among SMs continues into young adulthood. The association between identity-based stigma and suicidal behavior is stronger for LGB adults ages 18–26 relative to those 26 or older, signifying a critical period for prevention and intervention strategies. Our work also identifies sex differences in these observed age trends, and additional research should examine these patterns across, for example, racial and ethnic groups. Such studies will have the potential to better understand and ultimately address LGB-related health disparities when and for whom they are most needed.

References

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, West BT, McCabe SE. Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:35–45. doi: 10.1037/h0098851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. When black + lesbian + woman ≠ black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SR, Makadon HJ. If they don’t count us, we don’t count: Trump administration rolls back sexual orientation and gender identity data collection. LGBT Health. 2017;4:171–173. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of child psychology. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2006. pp. 1003–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in older adults. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2011;34:451–468. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Data from the National Vital Statistics System, Mortality. National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm. [Google Scholar]

- D’augelli A, Grossman A, Hershberger S, O’Connell T. Aspects of mental health among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2001;5:149–158. doi: 10.1080/13607860120038366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziak JJ, Li R, Wagner AT. Weighted TVEMSAS macro for accommodating survey weights and clusters. University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State; 2017. Retrieved from http://methodology.psu.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Sexual orientation and mental health in a birth cohort of young adults. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:971–981. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704004222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Pasley K. Sexual (minority) trajectories, mental health, and alcohol use: A longitudinal study of youth as they transition to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44:1508–1527. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0280-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Rice CE, Lanza ST, Russell ST. Using TVEM to explore social etiology: Sexual minority discrimination and suicide across the lifespan; Paper presented at the Society for Prevention Research 25th annual meeting; Washington, DC. 2017a. [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Rice CE, Lanza ST, Russell ST. Age-varying rates of sexual-identity based discrimination from 18 to 65: Findings from a national sample; Paper presented at the annual interdisciplinary population Health Research conferences; Austin. 2017b. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Barkan SE, Muraco A, Hoy-Ellis CP. Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:1802–1809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, Dunlap S. Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prevention Sciences. 2014;15:350–363. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Amsbary M, Chu A, Sigman R, Kali J, Sugawana Y, Goldstein R. Source and accuracy statement: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III) Rockville: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D’Augelli AR, et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality. 2010;58:10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL, Frost DM, Meyer IH, Pletta DR. Gay men’s health and identity: Social change and the life course. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2018;47:59–74. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-0990-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, O’Malley Olsen E, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, et al. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12—United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR Surveillance Summary. 2016;65:1–202. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise S, Hyde J. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49:142–167. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.637247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King S. Journal of GLBT family studies exploring the role of counselor support: gay, lesbian, bisexual, and questioning adolescents struggling with acceptance and disclosure. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2008;4:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self-harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Sidney S. Prevalence and health implications of anti-gay discrimination: A study of black and white women and men in the cardia cohort. International Journal of Health Services. 1997;27:157–176. doi: 10.2190/HPB8-5M2N-VK6X-0FWN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, Russell MA. Time-varying effect modeling to address new questions in behavioral research: Examples in marijuana use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2016;30:939–954. doi: 10.1037/adb0000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Neville HA. Construction and initial validation of the gendered racial microaggressions scale for black women. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2015;62:289–302. doi: 10.1037/cou0000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8:521–548. doi: 10.1177/1745691613497965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, et al. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1946–1952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2015;2:209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kessler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts versus suicide gestures: Analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:616–623. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. A changing epidemiology of suicide? The influence of birth cohort on suicide rates in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;114:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plöderl M, Tremblay P. Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. International Review of Psychiatry. 2015;27:367–385. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Russell ST. Understanding homophobic behavior and its implications for policy and practice. Theory Into Practice. 2013;52:264–271. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Mereish EH, DiGiovanni CD, Koenig BW. The effects of general and homophobic victimization on adolescents' psychosocial and educational concerns: The importance of intersecting identities and parent support. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:597–609. doi: 10.1037/a0025095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JP, Espelage DL, Rivers I. Developmental trends in peer victimization and emotional distress in LGB and heterosexual youth. Pediatrics. 2013;131:423–430. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Fish JN. Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2016;12:465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Toomey RB. Men’s sexual orientation and suicide: Evidence for US adolescent-specific risk. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Sinclair KO, Poteat VP, Koenig BW. Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:493–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM. Being out at school: The implications for school victimization and young adult adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:635–643. doi: 10.1037/ort0000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell MA, Vasilenko SA, Lanza ST. Age-varying links between violence exposure and behavioral, mental, and physical health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;59:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Shiyko MP, Li R, Li Y, Dierker L. A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:61–77. doi: 10.1037/a0025814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Russell ST. The role of sexual orientation in school-based victimization. Youth & Society. 2013;48:176–201. doi: 10.1177/0044118X13483778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: School victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1580–1589. doi: 10.1037/a0020705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for suicide prevention: Goals and objectives for action. Washington: HHS; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]