Abstract

This study aims to examine whether there were changes between 1995–2012 in the dietary glycaemic index (dGI) and glycaemic load (dGL) in Australian children (<16 years) according to three national surveys in 1995 (1995NS), 2007 (2007NS), and 2011–2012 (2012NS). Glycaemic index (GI) values of foods were assigned using published methodology. Plausible 24-h recall data from the 1995NS, 2007NS and 2012NS (weighted n = 2475, 4373 and 1691 respectively) were compared for differences in dGI and dGL, and the contribution to dGL from different foods using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc comparisons and linear regression. Decreasing trends across surveys were found in dGI and dGL (p < 0.001). Between 1995 and 2012, dGI and dGL per Megajoule (MJ) dropped by 2% and 6% respectively. The per capita dGL contribution from breads and bread rolls, fruit and vegetable juices, sweetened beverages and potatoes showed strong decreasing trends (R2 > 0.7). Our findings suggest that dGI and dGL of Australian youths declined between 1995 to 2012, which may be due to increased awareness of the GI concept and healthy diet, widened food choices and immigrants with diverse dietary habits. This may lower the future risks of chronic degenerative diseases in Australian youths.

Keywords: glycaemic index, glycaemic load, Australian children and adolescents, national nutrition surveys, trend analysis

1. Introduction

The relationship between dietary carbohydrates, postprandial glycaemia and health outcomes remains controversial. One measure of carbohydrate quality, the glycaemic index (GI), was first introduced in 1981 as a metric describing the extent to which blood glucose is raised by available carbohydrates in different foods [1]. By definition, low GI foods have GI values less than 55 (e.g., most dairy products), moderate GI from 56 to 69 (e.g., rice noodles, honey) and high GI at or above 70 (e.g., refined carbohydrates such as white rice) [2]. A lower GI indicates that the carbohydrates in a given food has a lower effect on postprandial blood glucose and possibly insulin responses. In contrast, the carbohydrates in high GI foods will lead to a greater surge of postprandial blood glucose level [3]. Since GI relates only to the quality of the carbohydrate, the concept of glycaemic load (GL) was proposed by Salmeron et al. [4] to represent both the quality and quantity (portion size) of carbohydrates. GL has been shown to be superior to the absolute amount of carbohydrate alone in predicting postprandial glycaemia in the context of both single foods and mixed meals [5].

Through the GI symbol program, popular press, television, advertising and the internet, Australian consumers have been exposed to the GI concept for over two decades [6,7,8,9]. Over the same timeframe, there have been changes in food availability, macronutrient distribution [10], food commodity groups [11] and health education in schools [12]. It is therefore reasonable to suggest changes in carbohydrate quality may have also taken place.

Previous studies in adults have reported association between high GI/GL intake with higher risk of diabetes, cancer, central obesity and higher BMI [13,14,15,16,17]. Studies in adolescents showed a positive association between GI/GL with blood pressure and risk of overweight/obesity [18,19]. An analysis of longitudinal trends in dGI/dGL of children can provide insights into education and policy changes needed to encourage healthier sources of carbohydrate energy which may help reduce the risk of chronic degenerative diseases on a population scale.

Our group have previously investigated the cross-sectional dietary data of Australian adolescents in 2007 and 2012 and the changes in healthy and unhealthy food intakes between 1995 and 2007, where we showed that Australian youths were generally had a healthier diet in 2007 than in 1995, and they appeared to have a lower dGI than European children in 2011–2012 [20,21,22]. However, to our knowledge, no study has explored dGI/dGL trends over time in children and adolescents. Using three national surveys can also provide us with additional information on the trends compared with only two years of data available in our previous analyses. The objectives of this study were to examine the current status and trends in dGI, dGL, and the major contributory food groups in Australian children aged 2 to 16 years according to national dietary surveys available to date conducted in 1995, 2007 and 2012. We hypothesized there may have been a decrease in dGI/dGL in Australian children and adolescents over time due to increased awareness of the GI concept, changes in food availability, macronutrient distribution and health education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Used

2.1.1. 1995 Australian National Nutrition Survey (1995NS)

The 1995NS was conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and the Department of Health together with the 1995 National Health Survey [23]. Data collection was conducted seven days a week between February 1995 and March 1996 [24]. Information about food and beverage intake, usual frequency of intake, eating habit, attitudes and physical measurements of Australians population aged two year-old or above was collected (n = 13,858) with a 61.4% response rate. Participants were selected randomly from dwellings in different State and Territories. Dietary intake was assessed using a single 24-h recall, and a subset of the sample (76.2% of those aged 12 and over) also completed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [23]. However the FFQ data were not used in the current analysis. Children aged 15 to 16 years provided their own dietary recall while parents, guardians or close relatives were responsible for providing the information for children aged 14 years or below [25,26]. Among all the participants in 1995NS, 2729 (19.7%) were aged between 2 and 16 inclusively.

2.1.2. 2007 Australian National Children’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (2007NS)

Details and cross-sectional dGI/dGL data of the 2007NS were previously described [21]. In brief, information on dietary intake, physical activity level (PAL) and demographic characteristics of randomly selected children and adolescents aged 2 to 16 years (n = 4837) from all Australian states and territories were collected with a response rate of 40%. Data collection occurred between February 2007 and August 2007. Dietary data were collected using a 24-h recall during face-to face home visits, and the majority of the sample (n = 4658) completed a second 24-h recall during a telephone interview conducted 7–21 days after the home visit. The first and second interview were conducted on different day types (weekdays/weekends) when possible. Care-givers provided dietary recall information for children aged 2 to 8 years while children aged nine years or above provided their own dietary recall [25,27,28].

2.1.3. 2011-12 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (2012NS)

Details and cross-sectional dGI/dGL data of the 2012NS have been previously described by our group [20]. In brief, respondents were randomly selected from 9500 private dwellings across Australia except for very remote areas and some non-private dwellings, e.g., hotels and hospitals. Dietary and physical activity information of the Australian population aged two years or above (n = 12,153) were collected from May 2011 to June 2012 from 12,366 dwellings with a 77% response rate. Data were mainly collected on Monday to Saturday depending on respondents’ availability and were occasionally collected on Sunday when specifically requested by respondents. Dietary data were collected using a 24-h recall during face-to-face home visits, and a second 24-h recall during a telephone interview was collected in ~60% of subjects at least eight days after the home visit. Adults were responsible for providing full food recall and responding to the physical activity questions for children aged 2 to 5 years, while children aged 6 to 8 years can assist in the recall. Children aged 9 to 11 years were interviewed directly with adults assisting, and children aged 12 to 14 years answered the questions themselves with adults in the same room. Those aged 15 to 17 years were interviewed personally with parental consent [26,29,30,31,32]. Among all the participants in 2012NS, 2548 (20.9%) were aged between 2 and 16 years inclusively.

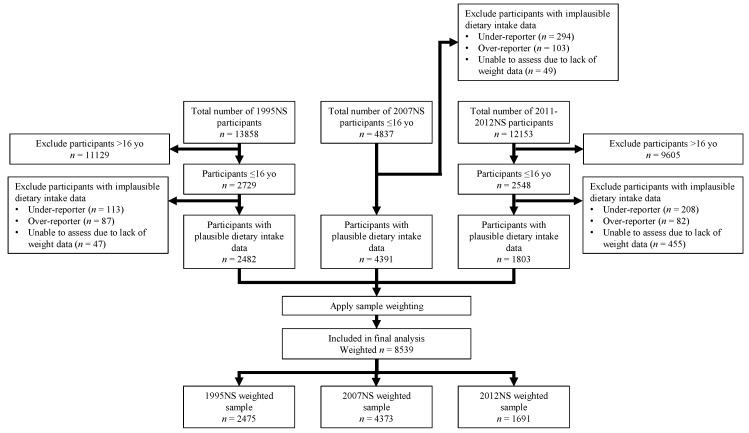

To allow direct comparison between surveys, only data from the first 24-h recall in the three surveys were used due to the low response rate of the second 24-h recall in the 1995NS; and only data from subjects aged 2 to 16 years were used as the 2007NS did not include adolescents aged 17 to 18 years. Data from the three surveys were combined into one dataset for analysis. A flow-of-participants diagram is available as Figure A1.

2.2. Dietary Glycemic Load and Dietary Glycemic Index Calculation

GI values were assigned to foods in AUSNUT1999 [33] (for 1995NS), AUSNUT2007 [34] (for 2007NS) and AUSNUT2011-2013 [35] (for 2012NS) food composition tables as previously described [36]. These values were then matched with the food intake of the respondents of the three surveys. GL of each food item was calculated by multiplying the GI by the available carbohydrates in a serving of the food. dGL was the sum of GL from all the foods reported in the 24-h recall while dGI was calculated by dividing an individual’s dGL by the total available carbohydrates intake of that person, expressed as a percentage.

2.3. Re-Coding and Classification of Food Groups in the Three Surveys

Food groups in the three AUSNUT databases were recoded into similar food groups for comparability purposes as described previously [37]. The final recoding table is shown in the Table A1.

2.4. Data Cleaning

Data were cleaned as previously described [37]. A default PAL of 1.55 was assigned to participants without PAL data, which included participants aged ≤8 years in the 2007NS (n = 2494), and all participants in 1995NS and 2012NS. For children aged 9 to 16 in 2007NS, PAL was calculated by activity data collected using a validated 24-h recall [30]. All participants with energy intake to basal metabolic rate ratio (EI:BMR) outside the 95%CI calculated based on the Goldberg cut-off for specific PAL method were consider to have extremely implausible food intake. Value of CVwB, CVtP and CVwEI used in the calculation were set at 8.5, 15 and 23 respectively according to previous studies [38,39]. Using PAL of 1.55 as an example, the cut-off point was calculated to be 0.87–2.75. For 1995NS, 2007NS and 2012NS, 200 out of 2729 (73%, with 113 extreme under- and 87 extreme over-reporters), 397 out of 4837 (5.1%, with 294 extreme under- and 103 extreme over-reporters) and 745 out of 2548 (31.4%, with 208 extreme under- and 82 extreme over-reporters) were excluded from the analysis. A further 551 (n = 47, 49 and 455 for 1995NS, 2007NS and 2012NS respectively) respondents who had no weight data, which disallowed the computation of the energy intake to basal metabolic rate ratio (EI:BMR), were also excluded. Sensitivity analyses were performed where data of all subjects including under- and over-reporters were used (Table A2, Table A3, Table A4, Table A5 and Table A6), and no material difference in the findings and conclusions were observed. Thus in this study we excluded under- and over-reporters to obtain more accurate population estimates.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

This secondary analysis was registered at anzctr.org.au (reference number: ACTRN12617000992303). Data were weighted to adjust for over- and/or under-sampling in terms of age, gender and region which may occur due to errors related to scope and coverage in random sampling and non-response bias, so as to represent Australian children and adolescents. The sample weightings supplied with the survey datasets were readjusted to account for the exclusion of extreme under- and over-reporters. Comparisons of dGI, dGL and percentage energy from different nutrients between the three surveys were done using one-way ANOVA. The same was used for the comparison of the top contributors of dGL food groups, both per capita and per consumer. Percentage of consumers were also stated in the per consumer table. Food groups with less than 10 consumers were excluded as they were considered non-representative. Results were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) and were ranked in the GL contributors table. Bonferroni post hoc analysis was conducted to test for difference between any two surveys. Linear regression on the median BMI, GI, GL, different nutrients and per consumer top GL contributing food groups were also done to examine whether linear trends exist across the three surveys. Median was used as it is less likely to be affected by outliers, or skewed by zero (i.e., non-consumers). Mean instead of median was used for the linear regression on per capita top GL contributing food groups as the majority of the medians were zero. A linear regression model with an R2 > 0.7 was considered a good fit. Multiple linear regression was performed using intake of energy and the top 20 GL contributing food groups as independent variables to describe the inter-individual variations in dGI and dGL. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Co. Ltd, Armonk, NY, USA), assuming normal distribution [30,40]. Due to the large number of comparisons made, a p value of 0.001 was set to indicate statistical significance [41].

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

The analysis included a weighted sample of 8539 participants with 2475 from 1995NS, 4373 from 2007NS and 1691 from 2012NS as shown in Table 1. The three surveys had similar male:female ratios; however the 2012NS had more respondents aged 9 to 13 years and fewer respondents aged 14 to 16 years when compared with the other two surveys. It also included more non-Australian born respondents than the two earlier surveys (p < 0.001). A higher proportion of excluded participants were from the 14 to 16 years age group (30.3% vs. 19.6%), while a lower proportion were from 2 to 3 years (16.9 vs. 20.4%) and 4 to 8 years age groups (24.1% vs. 31.0%) when compared with included participants (p < 0.001). There were no other significant differences between excluded vs. included participants in terms of sex, and country of birth.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of included participants.

| 1995NS | 2007NS | 2012NS | p Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n 2 | 2475 | 4373 | 1691 | - |

| Male (%) | 51.6 | 51.7 | 51.5 | 0.984 |

| Age groups (%) 3 | ||||

| 2–3 years | 13.4 | 13.2 | 12.7 | 0.181 |

| 4–8 years | 34.3 | 34.4 | 32.6 | |

| 9–13 years | 33.7 | 33.4 | 37.3 | |

| 14–16 years | 18.6 | 19.1 | 17.4 | |

| Country of birth (%) | ||||

| Australia | 94.3 | 92.5 | 90.2 | <0.001 |

| Others | 5.7 | 7.5 | 9.8 |

1 p value tested by chi-squared test for differences between the three surveys; 2 The sample were weighted and extreme under- and over-reporters were excluded; 3 Age groups as defined in the 2007 Children’s Survey; due to rounding to 1 decimal place the % may add up to more than 100%.

3.2. Trends in BMI, GI, GL, Energy, Macronutrients and Fiber Intake

Table 2 shows the mean BMI, dGI, dGL and the daily percentage energy contribution from selected macronutrients across the three surveys. No significant difference or trend was found in the mean BMI across the surveys. General decreasing trends were found in the median dGI, dGL, and GL per MJ, but the magnitude was usually small. Significant decreasing trends were also found in the median energy intake and percentage energy from sugars (p < 0.001). On the other hand, median percentage energy from starch had an increasing trend.

Table 2.

Mean ± SD daily glycemic index, glycemic load and intake of macronutrients of respondents of the three surveys.

| 1995NS | 2007NS | 2012NS | ptrend 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) 2 | 18.3 ± 3.4 | 18.5 ± 3.6 | 18.6 ± 3.5 | 0.033 |

| Dietary GI | 56.7 ± 5.1 | 54.2 ± 5.6 3 | 55.4 ± 5.3 3,4 | <0.001 |

| Dietary GL | 153.0 ± 58.6 | 141.0 ± 54.5 3 | 135.6 ± 50.0 3 | <0.001 |

| Dietary GL (g/MJ) | 17.9 ± 3.3 | 16.7 ± 3.3 3 | 16.8 ± 3.3 3 | <0.001 |

| Energy (kJ) | 8590 ± 2980 | 8500 ± 2890 | 8100 ± 2640 3,4 | <0.001 |

| Energy from fat (%) | 33.2 ± 6.6 | 30.6 ± 6.9 3 | 31.2 ± 6.9 3 | <0.001 |

| Energy from saturated fat (%) | 14.6 ± 4.0 | 13.7 ± 4.1 3 | 13.2 ± 4.0 3,4 | <0.001 |

| Energy from protein (%) | 14.4 ± 3.7 | 16.4 ± 4.5 3 | 15.9 ± 4.2 3,4 | <0.001 |

| Energy from carbohydrates (%) | 53.6 ± 8.2 | 52.2 ± 8.1 3 | 51.5 ± 7.9 3 | <0.001 |

| Energy from sugars (%) | 26.4 ± 8.9 | 25.6 ± 7.9 3 | 22.9 ± 7.6 3,4 | <0.001 |

| Energy from starch (%) | 25.3 ± 7.1 | 26.0 ± 7.4 3 | 26.9 ± 7.5 3,4 | <0.001 |

| Fibre density (g/MJ) | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.9 3 | 2.6 ± 1.0 3 | <0.001 |

1 ptrend from linear regression test for trends in median of the three surveys; 2 n = 2435, 4373 and 1684 due to missing values; 3 p < 0.001 compared with 1995NS; 4 p < 0.001 compared with 2007NS.

3.3. GL Contribution, Per Capita

Table 3 shows the top GL contributing food groups in the three surveys. Breads were found to be the highest in all three surveys (18.1% in 1995, 15.6% in 2007, 15.0% in 2012). Ready to eat breakfast cereal (9.2%, 9.2%, 6.7%) and juices (9.9%, 6.5%, 5.5%) were in the top five in each case. Potatoes (7.5%, 5.7%, 4.3%) and sweetened beverage (5.9%, 3.8%, 3.9%) were in the top five in 1995 but the ranking dropped to 6th and 7th in 2012 respectively. Although the ranking remained high, their contributing percentage dropped. Cereal-based dishes ranked 6th and 9th in 1995 and 2007 respectively but then rose to 2nd in 2012 (3.9%, 3.6%, 10.0%). The rank of cow’s milk dropped from 7th in 1995 and 2007 to 11th in 2012, while frozen milk products dropped from 11th to 21st then 19th. The ranking of starches (3.2%, 4.1%, 4.6%) rose from 9th to 6th and 5th, while savory biscuits (1.5%, 2.7%, 3.2%) rose from 18th to 12th and 10th. Fancy breads also went up from 20th to 13th and 12th in the same period.

Table 3.

Per capita mean ± SD comparison of the highest contributors to glycemic load in the three surveys.

| Food Groups | 1995NS | 2007NS | 2012NS | β ± SE 4 | R2 | ptrend 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Mean ± SD | Rank | Mean ± SD | Rank | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Bread and bread rolls | 1 | 18.1 ± 13.6 | 1 | 15.6 ± 13.4 2 | 1 | 15.0 ± 12.9 | −0.197 ± 0.000 | 0.998 | <0.001 |

| Fruits and vegetables juices | 2 | 9.9 ± 10.5 | 3 | 6.5 ± 8.3 2 | 4 | 5.5 ± 8.1 2,3 | −0.279 ± 0.000 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 3 | 9.2 ± 10.5 | 2 | 9.2 ± 11.2 | 3 | 6.7 ± 9.6 2,3 | −0.086 ± 0.001 | 0.304 | <0.001 |

| Potatoes | 4 | 7.5 ± 10.5 | 4 | 5.7 ± 9.0 | 6 | 4.3 ± 8.5 | −0.178 ± 0.000 | 0.942 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened beverages | 5 | 5.9 ± 10.3 | 8 | 3.8 ± 7.6 2 | 7 | 3.9 ± 8.1 2 | −0.141 ± 0.000 | 0.942 | <0.001 |

| Cereal based dishes | 6 | 3.9 ± 9.1 | 9 | 3.4 ± 8.0 | 2 | 10.0 ± 15.0 2,3 | 0.201 ± 0.004 | 0.238 | <0.001 |

| Dairy milk | 7 | 3.2 ± 3.6 | 7 | 3.8 ± 4.1 2 | 11 | 3.0 ± 4.0 3 | 0.017 ± 0.001 | 0.108 | <0.001 |

| Cake-type dessert | 8 | 3.2 ± 7.7 | 10 | 3.1 ± 7.3 | 8 | 3.8 ± 9.3 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 0.106 | <0.001 |

| Flours, cereals and starches | 9 | 3.2 ± 9.8 | 6 | 4.1 ± 10.9 | 5 | 4.6 ± 12.3 2 | 0.082 ± 0.000 | 0.959 | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuits | 10 | 2.8 ± 5.3 | 11 | 2.7 ± 5.4 | 9 | 3.4 ± 6.3 3 | 0.011 ± 0.000 | 0.065 | <0.001 |

| Frozen milk products | 11 | 2.4 ± 4.6 | 21 | 1.6 ± 3.6 2 | 19 | 1.6 ± 3.7 2 | −0.057 ± 0.000 | 0.951 | <0.001 |

| Pastas | 12 | 2.2 ± 6.2 | 5 | 4.2 ± 8.5 2 | 16 | 1.9 ± 6.2 3 | 0.062 ± 0.002 | 0.125 | <0.001 |

| Sugar, honey and syrups | 13 | 2.1 ± 3.8 | 19 | 1.8 ± 3.7 | 18 | 1.6 ± 3.9 2 | −0.028 ± 0.000 | 0.929 | <0.001 |

| Pome fruit | 14 | 2.0 ± 3.6 | 15 | 2.3 ± 3.8 | 13 | 2.7 ± 4.3 2,3 | 0.033 ± 0.000 | 0.742 | <0.001 |

| Pastries | 15 | 2.0 ± 5.4 | 18 | 2.0 ± 5.6 | 15 | 1.9 ± 5.6 | −0.002 ± 0.000 | 0.097 | <0.001 |

| Other confectionery | 16 | 1.9 ± 5.6 | 14 | 2.6 ± 7.3 2 | 23 | 1.3 ± 3.8 3 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Chocolates | 17 | 1.7 ± 4.3 | 16 | 2.1 ± 5.5 | 21 | 1.4 ± 4.5 3 | 0.004 ± 0.000 | 0.008 | <0.001 |

| Savory biscuits | 18 | 1.5 ± 4.1 | 12 | 2.7 ± 5.9 2 | 10 | 3.2 ± 7.3 2 | 0.101 ± 0.000 | 0.989 | <0.001 |

| Tropical and subtropical fruit | 19 | 1.4 ± 3.6 | 17 | 2.0 ± 4.3 2 | 14 | 2.0 ± 4.6 2 | 0.041 ± 0.000 | 0.945 | <0.001 |

| Fancy breads | 20 | 1.3 ± 4.5 | 13 | 2.7 ± 7.0 2 | 12 | 2.9 ± 7.7 2 | 0.110 ± 0.000 | 0.973 | <0.001 |

| Potato snacks | 21 | 1.1 ± 2.9 | 25 | 1.2 ± 3.6 | 22 | 1.3 ± 4.1 | 0.008 ± 0.000 | 0.588 | <0.001 |

| Confectionery based dishes | 22 | 1.0 ± 3.6 | 28 | 0.8 ± 3.1 | 28 | 0.9 ± 3.0 | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Batter-based product | 23 | 1.0 ± 4.5 | 20 | 1.7 ± 5.6 2 | 27 | 1.0 ± 4.0 3 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.157 | <0.001 |

| Cereal-, fruit-, nut-,seed-bars | 24 | 1.0 ± 2.6 | 22 | 1.4 ± 4.0 | 17 | 1.8 ± 4.5 | 0.043 ± 0.000 | 0.878 | <0.001 |

| Extruded snacks | 25 | 0.8 ± 3.4 | 44 | 0.2 ± 1.7 2 | 33 | 0.6 ± 3.2 3 | −0.033 ± 0.000 | 0.523 | <0.001 |

| Milk and milk products based dishes | 26 | 0.8 ± 2.8 | 35 | 0.5 ± 2.3 2 | 39 | 0.3 ± 1.9 2 | −0.027 ± 0.000 | 0.980 | <0.001 |

| Poultry based dishes | 27 | 0.6 ± 2.3 | 33 | 0.6 ± 2.1 | 20 | 1.5 ± 4.6 2,3 | 0.031 ± 0.001 | 0.878 | <0.001 |

1 ptrend from linear regression test for trends in means of the three surveys. 2 p < 0.001 compared with 1995NS. 3 p < 0.001 compared with 2007NS. 4 β ± SE indicates the change in unit of the food item per year.

The results of linear regression showed that there were decreasing trends (ptrend < 0.001 and R2 > 0.7) in the mean percentage GL contribution of breads and bread rolls, fruit and vegetable juices, breakfast cereals (ready to eat), potatoes, sweetened beverages, sugar, honey and syrup, frozen milk products, and milk and milk product-based dishes. On the other hand, there were increasing trends (ptrend < 0.001 and R2 > 0.7) for flours, cereal and starches, savory biscuits, fancy breads, pome fruits, tropical and subtropical fruits, poultry-based dishes, and cereal-, fruit-, nut-, and seed-bars groups. For the rest of the food groups, while the linear trend was statistically significant, the R2 indicated that year of survey was not a good predictor of change in mean percentage dGL contribution.

3.4. GL Contribution, Per Consumer

Per consumer percentage GL contribution is shown in Table 4. Flours, cereals and starches ranked the 1st in all three surveys (22.8%, 22.2%, 27.3%). Breads ranked 2nd in 1995 and 2007 and 3rd in 2012 (21.4%, 20.2%, 20.3%). Cereal-based dishes ranked 3rd in 1995, dropped to 6th in 2007, then rose to 2nd in 2012 (16.6%, 15.2%, 23.7%). Hot porridge (16.4%, 17.5%, 15.5%) and ready-to-eat (15.8%, 17.2%, 15.3%) breakfast cereals were among top 5 in 1995 and 2007 and then dropped to 7th and 8th respectively in 2012. Rank of sweetened beverage dropped from 6th to 11th and then 16th (15.4%, 12.2%, 10.5%). Pastas (14.1%, 16.0%, 16.9%) went up from 9th to 5th and to 6th and cake-type desserts (14.0%, 14.1%, 18.5%) went up from 10th to 8th and then 4th. The ranking for fruit and vegetable juices (13.9%, 10.9%, 11.2%) dropped from 11th in 1995 to 14th in 2007 and 2012.

Table 4.

Per consumer mean ± SD comparison of the highest contributors to glycemic load in the three surveys.

| Food Groups | 1995NS | 2007NS | 2012NS | β ± SE 5 | R2 | ptrend 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Mean ± SD | % 1 | Rank | Mean ± SD | % 1 | Rank | Mean ± SD | % 1 | ||||

| Flours, cereals and starches | 1 | 22.8 ± 15.6 | 13.8 | 1 | 22.2 ± 15.4 | 18.7 | 1 | 27.3 ± 16.8 | 16.9 | 0.085 ± 0.009 | 0.061 | <0.001 |

| Bread and bread rolls | 2 | 21.4 ± 12.1 | 84.5 | 2 | 20.2 ± 11.8 3 | 77.3 | 3 | 20.3 ± 10.9 | 73.9 | −0.071 ± 0.000 | 0.797 | <0.001 |

| Cereal based dishes | 3 | 16.6 ± 11.9 | 23.6 | 6 | 15.2 ± 10.4 | 22.6 | 2 | 23.7 ± 14.3 3,4 | 42.3 | 0.350 ± 0.010 | 0.348 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (hot porridge) | 4 | 16.4 ± 7.7 | 2.5 | 3 | 17.5 ± 12.8 | 3.3 | 7 | 15.5 ± 11.3 | 5.3 | −0.068 ± 0.006 | 0.295 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 5 | 15.8 ± 9.2 | 58.0 | 4 | 17.2 ± 9.9 3 | 53.4 | 8 | 15.3 ± 8.9 4 | 43.9 | 0.067 ± 0.002 | 0.246 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened beverages | 6 | 15.4 ± 11.5 | 38.2 | 11 | 12.2 ± 9.0 3 | 31.1 | 16 | 10.5 ± 10.4 3,4 | 37.2 | −0.235 ± 0.001 | 0.945 | <0.001 |

| Potatoes | 7 | 14.8 ± 10.5 | 50.7 | 9 | 13.3 ± 9.4 3 | 42.9 | 12 | 12.5 ± 10.4 3 | 34.3 | −0.158 ± 0.001 | 0.893 | <0.001 |

| Batter-based products | 8 | 14.4 ± 9.5 | 7.1 | 10 | 13.1 ± 10.1 | 12.6 | 11 | 12.6 ± 7.8 | 7.7 | −0.125 ± 0.000 | 0.988 | <0.001 |

| Pastas | 9 | 14.1 ± 8.9 | 15.4 | 5 | 15.7 ± 9.7 | 26.6 | 6 | 16.9 ± 9.9 | 10.9 | 0.097 ± 0.000 | 0.991 | <0.001 |

| Cake-type dessert | 10 | 14.0 ± 10.4 | 22.5 | 8 | 14.1 ± 9.6 | 21.7 | 4 | 18.5 ± 12.4 3,4 | 20.5 | 0.148 ± 0.006 | 0.245 | <0.001 |

| Fruits and vegetables juices | 11 | 13.9 ± 10.0 | 71.2 | 14 | 10.9 ± 8.2 3 | 59.3 | 14 | 11.2 ± 7.5 3 | 39.4 | −0.187 ± 0.001 | 0.896 | <0.001 |

| Fancy breads | 12 | 13.0 ± 7.5 | 9.9 | 7 | 14.8 ± 9.4 | 18.0 | 5 | 17.5 ± 10.0 3,4 | 16.6 | 0.193 ± 0.005 | 0.560 | <0.001 |

| Pastries | 13 | 11.0 ± 8.1 | 17.8 | 13 | 11.9 ± 8.4 | 16.6 | 10 | 12.9 ± 8.7 | 14.4 | 0.153 ± 0.001 | 0.918 | <0.001 |

| Extruded snacks | 14 | 9.8 ± 7.0 | 8.6 | 20 | 8.7 ± 6.5 | 2.5 | 15 | 10.8 ± 9.3 | 5.3 | −0.029 ± 0.003 | 0.183 | <0.001 |

| Dried fruit, preserved fruit | 15 | 8.7 ± 8.2 | 5.0 | 18 | 8.7 ± 7.8 | 6.9 | 19 | 9.2 ± 8.1 | 5.1 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.518 | <0.001 |

| Other confectionery | 16 | 8.6 ± 9.4 | 21.7 | 12 | 11.9 ± 11.6 3 | 21.7 | 32 | 6.8 ± 6.4 4 | 18.6 | 0.127 ± 0.006 | 0.222 | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuits | 17 | 8.2 ± 6.1 | 34.9 | 22 | 8.6 ± 6.5 | 31.6 | 18 | 9.5 ± 7.2 3 | 35.5 | 0.052 ± 0.001 | 0.628 | <0.001 |

| Confectionery based dishes | 18 | 8.0 ± 6.6 | 12.9 | 24 | 8.2 ± 6.4 | 9.3 | 24 | 7.7 ± 4.9 | 12.2 | 0.044 ± 0.001 | 0.511 | <0.001 |

| Savory biscuits | 19 | 7.6 ± 6.0 | 20.2 | 16 | 9.9 ± 7.5 3 | 27.1 | 13 | 12.1 ± 9.5 3,4 | 26.7 | 0.196 ± 0.001 | 0.914 | <0.001 |

| Frozen milk products | 20 | 7.4 ± 5.2 | 32.4 | 34 | 6.4 ± 4.8 3 | 24.9 | 29 | 6.9 ± 4.7 | 22.7 | −0.039 ± 0.001 | 0.497 | <0.001 |

| Tropical and subtropical fruit | 21 | 7.2 ± 4.9 | 19.5 | 25 | 8.1 ± 5.1 | 25.1 | 20 | 9.2 ± 5.6 3 | 21.6 | 0.088 ± 0.000 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Milk and milk products based dishes | 22 | 7.0 ± 4.7 | 11.7 | 26 | 8.0 ± 4.8 | 6.4 | 31 | 6.9 ± 5.4 | 5.1 | 0.057 ± 0.004 | 0.220 | <0.001 |

| Fruit dishes | 23 | 6.9 ± 3.7 | 0.5 | 15 | 10.9 ± 7.1 | 0.4 | 33 | 6.4 ± 7.5 | 0.7 | −0.071 ± 0.057 | 0.038 | 0.219 |

| Fruit combinations | 24 | 6.6 ± 6.7 | 2.4 | 31 | 7.6 ± 4.4 | 3.1 | 23 | 8.6 ± 6.3 | 3.1 | 0.142 ± 0.000 | 0.998 | <0.001 |

| Flavored milks | 25 | 6.6 ± 4.3 | 6.3 | 30 | 7.7 ± 4.3 | 8.2 | 9 | 13.1 ± 9.1 3,4 | 9.6 | 0.234 ± 0.007 | 0.607 | <0.001 |

| Infant foods | 26 | 6.4 ± 6.0 | 0.6 | 36 | 6.2 ± 4.8 | 0.4 | # | 9.3 ± 7.7 | 0.2 | 0.027 ± 0.007 | 0.326 | <0.001 |

| Chocolates | 27 | 6.4 ± 6.2 | 26.7 | 23 | 8.3 ± 8.2 | 25.3 | 25 | 7.5 ± 7.8 | 19.1 | 0.061 ± 0.000 | 0.906 | <0.001 |

| Potato snacks | 28 | 6.1 ± 4.1 | 18.4 | 33 | 6.9 ± 6.0 | 16.7 | 26 | 7.4 ± 7.2 | 17.5 | 0.022 ± 0.000 | 0.944 | <0.001 |

| Pretzels and other snacks | 29 | 6.0 ± 3.5 | 0.7 | 35 | 6.4 ± 5.8 | 5.4 | 39 | 5.8 ± 5.0 | 4.6 | −0.108 ± 0.001 | 0.980 | <0.001 |

| Cereal-, fruit-, nut-, seed-bars | 30 | 6.0 ± 3.5 | 16.4 | 17 | 9.4 ± 5.6 3 | 14.8 | 17 | 10.3 ± 5.2 3 | 17.4 | 0.236 ± 0.000 | 0.998 | <0.001 |

| Infant formulae/breast milk | # | 6.7 ± 15.8 | 0.04 | 21 | 8.7 ± 9.0 | 0.6 | # | 13.7 ± 17.3 | 0.4 | −0.042 ± 0.048 | 0.023 | 0.388 |

Post-hoc analysis was not performed for food group with any group having less than 2 consumers (infant foods and infant formulae/breast milk). Groups with less than 10 consumers were excluded from the ranking (marked with #). 1 Percentage of participants who consumed foods in the food group; 2 ptrend from linear regression test for trends in medians of the three surveys; 3 p < 0.001 compared with 1995NS; 4 p < 0.001 compared with 2007NS; 5 β ± SE indicates the change in unit of the food item per year.

Linear regression showed that there were decreasing trends (all ptrend < 0.001 and R2 > 0.7) in breads, potatoes, batter-based products, sweetened beverages, pretzels and other snacks, and fruit and vegetable juices from 1995 to 2012. On the other hand, increasing trends (all ptrend < 0.001 and R2 > 0.7) were found in pastas, pastries, savory biscuits, fruit combinations, chocolates, potato snacks, cereal-, fruit-, nut-, seed- bars and tropical fruits. For the rest of the food groups, either the model was not statistically significant or the R2 values were low, which suggested that year of survey was not a good predictor of median change in dGL contribution.

3.5. Inter-Individual Variations in Dietary GI and GL

The contribution of the top 20 GL food groups in both surveys to the inter-individual variation of dGI and dGL is presented in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. Overall, there were decreases over time in the inter-individual variation in dGI (R2: 0.441, 0.372 and 0.351 for 1995NS, 2007NS and 2012NS respectively) and dGL (R2: 0.888, 0.862 and 0.846 for 1995NS, 2007NS and 2012NS respectively) explained by these food groups.

Table 5.

The contribution of the top 20 GL food groups to inter-individual variations in dietary glycaemic index (dGI) and glycaemic load (dGL) in 1995NS (n = 2475).

| Food Groups | dGI | dGL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β ± SE | Partial R2 | P Value | β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value | |

| Model R2 = 0.441 | Model R2 = 0.888 | |||||

| Bread and bread rolls | 2.14 ± 0.14 | 0.087 | <0.001 | 17.20 ± 0.72 | 0.188 | <0.001 |

| Fruits and vegetables juices | −0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.013 | <0.001 | 3.11 ± 0.12 | 0.208 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 3.15 ± 0.23 | 0.070 | <0.001 | 33.25 ± 1.20 | 0.237 | <0.001 |

| Potatoes | 1.64 ± 0.08 | 0.133 | <0.001 | 6.56 ± 0.44 | 0.084 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened beverages | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.031 | <0.001 | 4.18 ± 0.15 | 0.231 | <0.001 |

| Cereal based dishes | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 0.009 | <0.001 | 4.15 ± 0.37 | 0.049 | <0.001 |

| Dairy milk | −0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.077 | <0.001 | −0.91 ± 0.16 | 0.014 | <0.001 |

| Cake-type dessert | −0.34 ± 0.16 | 0.002 | 0.034 | 10.33 ± 0.83 | 0.060 | <0.001 |

| Flours, cereals and starches | 1.12 ± 0.09 | 0.056 | <0.001 | 10.60 ± 0.48 | 0.164 | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuits | 0.28 ± 0.35 | <0.001 | 0.421 | 10.19 ± 1.80 | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| Frozen milk products | −0.68 ± 0.10 | 0.019 | <0.001 | 2.07 ± 0.51 | 0.007 | <0.001 |

| Pastas | −0.93 ± 0.10 | 0.038 | <0.001 | 2.68 ± 0.49 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| Sugar, honey and syrups | 1.46 ± 0.49 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 27.34 ± 2.54 | 0.045 | <0.001 |

| Pome fruit | −0.92 ± 0.07 | 0.059 | <0.001 | 1.55 ± 0.39 | 0.007 | <0.001 |

| Pastries | −0.43 ± 0.11 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 0.22 ± 0.56 | <0.001 | 0.697 |

| Other confectionery | 4.37 ± 0.40 | 0.046 | <0.001 | 46.43 ± 2.09 | 0.167 | <0.001 |

| Chocolates | −1.33 ± 0.33 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 7.90 ± 1.70 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| Savory biscuits | 2.22 ± 0.49 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 14.20 ± 2.53 | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| Tropical and subtropical fruit | −0.68 ± 0.16 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 4.55 ± 0.81 | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| Fancy breads | 1.48 ± 0.32 | 0.009 | <0.001 | 12.88 ± 1.65 | 0.024 | <0.001 |

β ± SE calculated using multiple linear regression, with energy and the food groups as the predictor variables. β expressed as change in dGI or dGL per 100 g increase in intake of the corresponding food group.

Table 6.

The contribution of the top 20 GL food groups to inter-individual variations in dietary glycaemic index (dGI) and glycaemic load (dGL) in 2007NS (n = 4373).

| Food Groups | dGI | dGL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Groups | β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value | β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value |

| Model R2 = 0.372 | Model R2 = 0.862 | |||||

| Breads, and bread rolls | 2.62 ± 0.13 | 0.091 | <0.001 | 15.45 ± 0.57 | 0.145 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 3.93 ± 0.19 | 0.086 | <0.001 | 33.54 ± 0.88 | 0.250 | <0.001 |

| Fruit and vegetables juices | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.001 | 0.118 | 3.08 ± 0.15 | 0.094 | <0.001 |

| Potatoes | 1.83 ± 0.08 | 0.102 | <0.001 | 7.49 ± 0.37 | 0.085 | <0.001 |

| Pastas | −0.54 ± 0.07 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 4.92 ± 0.30 | 0.059 | <0.001 |

| Flours, cereals and starches | 1.71 ± 0.08 | 0.097 | <0.001 | 13.60 ± 0.36 | 0.250 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened beverages | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.017 | <0.001 | 2.89 ± 0.12 | 0.114 | <0.001 |

| Dairy milk | −0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.035 | <0.001 | −0.58 ± 0.13 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| Cereal based dishes | 0.01 ± 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.850 | 3.64 ± 0.30 | 0.033 | <0.001 |

| Cake-type dessert | 0.02 ± 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.900 | 8.16 ± 0.74 | 0.028 | <0.001 |

| Fancy breads | 1.40 ± 0.21 | 0.010 | <0.001 | 12.46 ± 0.94 | 0.039 | <0.001 |

| Savory biscuits | 3.89 ± 0.39 | 0.022 | <0.001 | 19.49 ± 1.78 | 0.027 | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuits | 1.52 ± 0.32 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 16.71 ± 1.46 | 0.029 | <0.001 |

| Other confectionery | 5.68 ± 0.28 | 0.086 | <0.001 | 48.19 ± 1.28 | 0.247 | <0.001 |

| Pome fruit | −0.83 ± 0.07 | 0.036 | <0.001 | 2.19 ± 0.30 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| Chocolates | −0.15 ± 0.28 | <0.001 | 0.595 | 10.68 ± 1.26 | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| Pastries | 0.10 ± 0.10 | <0.001 | 0.324 | 2.32 ± 0.45 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| Tropical and subtropical fruit | −0.42 ± 0.10 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 3.40 ± 0.47 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| Sugar, honey and syrups | 2.01 ± 0.48 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 29.61 ± 2.16 | 0.041 | <0.001 |

| Batter-based product | 2.66 ± 0.22 | 0.032 | <0.001 | 16.03 ± 1.01 | 0.055 | <0.001 |

β ± SE calculated using multiple linear regression, with energy and the food groups as the predictor variables. β expressed as change in dGI or dGL per 100 g increase in intake of the corresponding food group.

Table 7.

The contribution of the top 20 GL food groups to inter-individual variations in dietary glycaemic index (dGI) and glycaemic load (dGL) in 2012NS (n = 1691).

| Food Groups | dGI | dL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Groups | β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value | β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value |

| Model R2 = 0.351 | Model R2 = 0.846 | |||||

| Breads, and bread rolls | 1.94 ± 0.21 | 0.049 | <0.001 | 13.18 ± 0.97 | 0.101 | <0.001 |

| Cereal based dishes | 0.53 ± 0.07 | 0.034 | <0.001 | 3.83 ± 0.32 | 0.077 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 2.93 ± 0.37 | 0.036 | <0.001 | 24.95 ± 1.72 | 0.112 | <0.001 |

| Fruit and vegetables juices | −0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.003 | 0.030 | 2.82 ± 0.25 | 0.069 | <0.001 |

| Flours, cereals and starches | 2.06 ± 0.14 | 0.119 | <0.001 | 16.05 ± 0.63 | 0.278 | <0.001 |

| Potatoes | 1.54 ± 0.13 | 0.076 | <0.001 | 6.52 ± 0.61 | 0.064 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened beverages | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 3.22 ± 0.17 | 0.185 | <0.001 |

| Cake-type dessert | −0.79 ± 0.20 | 0.010 | <0.001 | 6.24 ± 0.90 | 0.028 | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuits | −0.18 ± 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.660 | 13.67 ± 1.94 | 0.029 | <0.001 |

| Savory biscuits | 3.17 ± 0.43 | 0.032 | <0.001 | 18.26 ± 1.98 | 0.048 | <0.001 |

| Dairy milk | −0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.077 | <0.001 | −1.14 ± 0.22 | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| Fancy breads | 1.13 ± 0.30 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 10.56 ± 1.40 | 0.033 | <0.001 |

| Pome fruit | −0.81 ± 0.09 | 0.045 | <0.001 | 1.40 ± 0.42 | 0.007 | 0.001 |

| Tropical and subtropical fruit | −0.68 ± 0.18 | 0.009 | <0.001 | 3.44 ± 0.83 | 0.010 | <0.001 |

| Pastries | −0.64 ± 0.16 | 0.009 | <0.001 | 0.21 ± 0.76 | <0.001 | 0.786 |

| Pastas | 0.07 ± 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.601 | 3.16 ± 0.63 | 0.015 | <0.001 |

| Cereal-, fruit-, nut-, and seed-bars | 3.14 ± 0.73 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 21.13 ± 3.36 | 0.023 | <0.001 |

| Sugar, honey and syrups | 4.27 ± 0.82 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 43.35 ± 3.78 | 0.073 | <0.001 |

| Frozen milk products | −1.03 ± 0.19 | 0.017 | <0.001 | −0.41 ± 0.88 | <0.001 | 0.640 |

| Poultry based dishes | 0.44 ± 0.15 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.17 ± 0.68 | <0.001 | 0.804 |

β ± SE calculated using multiple linear regression, with energy and the food groups as the predictor variables. β expressed as change in dGI or dGL per 100 g increase in intake of the corresponding food group.

4. Discussion

In this analysis, we report downward trends in the mean dGI and dGL in Australian children between 1995 and 2012. Over this timeframe, major carbohydrate food groups made a smaller contribution to overall dGL. Energy-dense nutrient-poor food groups such as sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) and juice declined, while starch energy and cereals-based products, and savory biscuits increased.

Few observational studies [42,43] had examined longitudinal trends in dGI and dGL, or changes in the contribution of different food groups. To our knowledge, our study is the first utilizing a nationally representative sample to address this evidence gap. Results from the DONALD study provide interesting comparisons. Among German children in the DONALD study who were 7 to 8 years old in the 1990, 1996 and 2002 cross-sections, dGI increased from 55.1 to 56.0 then 56.5 in the 12 year period, while GL per MJ had increased from 16.7 to 17.5 then plateaued [42]. This contrasts with our finding that Australian children and adolescents had a lower dGL over a 17-year period, which could be largely explained by the diverging trends in carbohydrate food choices. The non-representative sample of high socio-economic status participants in the DONALD study may have different dietary habits, such as higher GI and GL diet, which may not represent the general population and led to the discrepancies.

As expected, breads made the highest contribution to dGL in the per capita analysis and ranked among the top three on a per consumer basis across all three surveys. Although there are low GI specialty breads on the market, most types have a relatively high GI [2,44]. A previous analysis of the 2012NS reported that two in three Australians consumed breads on the survey day [29]. Nonetheless, the contribution of breads to dGL fell progressively from 18% to 16% to 15% on a per capita basis in 1995, 2007 and 2012 respectively. One explanation may be the increasing popularity of branded whole grain breads that are specifically marketed on the basis of their low GI values. This is supported by our previous study [22] comparing the core food intake of Australian children between 1995 and 2007, which showed a decrease in per capita white bread intake from 61 to 41 g in 2 to 16 years old children, and an increase in wholegrain bread from 15 to 23 g.

The mean dGL contribution of cereal-based dishes increased markedly from 1995 to 2012. Their contribution to dGL increased from 4% to 10% per capita and from 17% to 24% per consumer. Other than an increase in consumption, the increases may also be influenced by changes in data collection and coding methods in the 2012NS [31]. Modifications were made to the AUSNUT2011-2013 classification system due to the changes in food supply across the years and to ensure sufficient details were captured to meet the needs of future users [45]. Thus some of the foods in the cereal-based dishes group in 2012NS were not included in AUSNUT1999 and AUSNUT2007, e.g., flavored rice and dumplings [46]. Similarly, in 1995NS and 2007NS, mixed foods such as burgers were split into individual ingredients (bun, patty and fillings), while in 2012NS, these foods were coded and reported as a single mixed food [30,31]. A 150 g hot dog which belonged to the cereal-based dishes group in 2012NS may have been separated into an 80 g sausage in the meat group with a 70 g bread roll in the cereal products group in 1995NS and 2007NS. As a result, it is possible that more foods were included in the cereal-based group in 2012NS, thereby increasing the GL contribution of this group.

The top five food groups per capita in 1995 (breads and bread rolls, fruit and vegetable juices, breakfast cereals (ready to eat), potatoes and SSB), had all fallen by 2012. On the other hand, the GL contribution of cereal-based dishes, cakes, flours, cereals and starches, and fruits rose. The decreased consumption of these carbohydrate-rich foods (breads and bread rolls, breakfast cereals (ready to eat) and potatoes) could be due to the increased popularity of low GI diet since around 2002, and low carbohydrate diets being introduced in Australia around 2004 [6,47]. Media coverage of the high amount of sugars in drinks, possible health risks brought by high fruit juice consumption, as well as the banning of SSBs in public schools in Australian states since 2007 may also have increased the awareness towards these drinks, and contributed to the decreasing trend in dGL contributed by SSBs and fruit juices [48,49,50], although SSB and fruit juices were still major food choices for certain children, contributing >10% to dGL on a per consumer basis across all three surveys. While fruit juice is rich in vitamins and phenolic antioxidants, its consumption as a replacement for whole fruits is currently discouraged [51].

From the multiple linear regression analysis, the decreasing R2 indicates the intake of the top 20 food groups contributing to GL explained less and less of the inter-individual variations in dGI and GL. This finding is consistent with our previous analysis in Australian adults [37]. Overall, our findings suggest that Australian children and adolescents are consuming a more diverse diet, or that their food intake patterns have changed in recent years. This could be due to increased awareness of healthy diets from the media, as well as the aforementioned regulations on SSBs which may have led to changes in the food and drinks consumption patterns. We performed post hoc analyses on changes in absolute carbohydrate intakes across the three surveys and found carbohydrate intake dropped by ~9% in this period (data not shown). In addition, data from the ABS showed household expenditure on certain foods such as breads, cakes and cereals have dropped, while that for meals out and takeaway foods had increased from 1998/99 to 2009/10 [52]. This may indicate that Australian youths may have a wider variety of food choices, hence developing a more diverse diet. On the other hand, migrants from South Asian and South-East Asian countries have contributed markedly to Australia’s population growth and undoubtedly to changing food trends. In June 2013, 6.4 million people from a total population of 23 million were overseas-born migrants. Those from China, India, Vietnam and other countries often maintain traditional eating habits and influence local food customs [53].

Our analyses showed decreasing trends in dGI and dGL of Australian youths from 1995 to 2012. The drop in dGI and dGL may provide a positive impact to the health of Australian youths, such as lower blood pressure and risk of overweight/obesity [18,19]. The risk of chronic degenerative diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases could also be seen if the low GI/GL dietary habit could persist to adulthood [13,14,15,16,17,54]. While the effect on some diseases at an individual level may not be huge, the population effect could be significant.

The strengths of this study include the use of representative national dietary data collected and analyzed using similar methods in all three surveys. The longitudinal statistical comparisons allowed us to distinguish statistically significant changes from apparent changes. GI values were assigned using a published method [36] which increases the reliability of the findings. While under-reporting is a likely component of all national dietary surveys [55], we applied a validated method to exclude extreme under- and over-reporters to improve the precision of population estimates [38]. Results of the sensitivity analyses indicated that exclusion of extreme mis-reporters did not bias the results.

Several limitations must also be considered. The 1995NS and 2012NS collected data throughout the whole year, while the 2007 survey was conducted during fall and winter months only. This may have led to differences in reported consumption of certain seasonal foods, particularly ice-cream and SSB. Second, children provided their own dietary recall at a younger age in the 2007NS and 2012NS, and different visual-aids were used for estimating portion size which may have impacted the accuracy of reporting. Finally, we utilized data from only 1 × 24-h recall as the response rate for the second recall in the 1995NS was low, although the use of 1 × 24-h recall is adequate in generating accurate population means [56].

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that dGI and dGL of Australian children and adolescents declined between 1995 to 2012. There were qualitative changes in the foods contributing the most to overall dGL. Breads, fruit juices, SSBs and potatoes showed decreasing trends on both a per capita and per consumer basis. These trends may have been influenced by increased awareness of benefits of healthy sources of carbohydrates, or changes in eating habits of the population, possibly as a result of increased knowledge of healthy diets and the GI concept, more diverse food choices, and immigration from Asian countries.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge The Glycemic Index Foundation (GIF) for providing the special edition of AUSNUT2011–2013 database for use in this study. The original data of the 2007NS were collected by the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization and the University of South Australia. The authors would like to thank the Australian Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing for providing the survey data via the Australian Social Science Data Archive. The original data of the 1995NS and 2012NS were collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The authors declare that those who carried out the original analysis and collection of the data bear no responsibility for further analysis or interpretation included in the manuscript.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Flow of participants.

Table A1.

Re-coding of food groups in the AUSNUT databases.

| New Code | New Food Group | 1995NS Code | 1995NS Food Group | 2007NS Code | 2007NS Food Group | 2012NS Code | 2012NS Food Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 111 | Tea | 111 | Tea | 111 | Tea | 111 | Tea |

| 112 | Coffee and coffee substitute | 112 | Coffee and coffee substitutes | 112 | Coffee and coffee substitutes | 112 | Coffee and coffee substitutes |

| 113 | Fruit and vegetable juices and drinks | 113 | Fruit and vegetables juices and drinks | 113 | Fruit and vegetable juices, and drinks | 113 | Fruit and vegetables juices and drinks |

| 114 | Cordials | 114 | Cordials | ||||

| 114 | Sweetened beverages | 114 | Soft drinks, flavored mineral waters and electrolyte drinks | 115 | Soft drinks, and flavored mineral waters | 115 | Soft drinks, and flavored mineral waters |

| 116 | Electrolyte, energy and fortified drinks | 116 | Electrolyte, energy and fortified drinks | ||||

| 115 | Mineral waters | 115 | Mineral waters and water | 117 | Mineral waters and water | 117 | Waters, municipal and bottled, unflavored |

| 116 | Other beverage flavorings and prepared beverages | 116 | Water with other additions as a beverage | 118 | Other beverage flavorings and prepared beverages | 118 | Other beverage flavorings and prepared beverages |

| 301 | Beverage flavorings | ||||||

| 121 | Flours and other cereal grains and starches | 121 | Flours and other cereal grains and starches | 121 | Flours and other cereal grains and starches | 121 | Flours and other cereal grains and starches |

| 126 | Rice and rice products | ||||||

| 122 | Bread and bread rolls | 122 | Regular breads, and rolls | 122 | Regular breads, and bread rolls (plain/unfilled/untopped varieties) | 122 | Regular breads, and bread rolls (plain/unfilled/untopped varieties) |

| 123 | Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 123 | BF cereals, plain, single source | 125 | Breakfast cereals and bars, unfortified and fortified varieties | 125 | Breakfast cereals, ready to eat |

| 124 | Fancy breads | 124 | Fancy breads, flat breads, English-style muffins and crumpets | 123 | English-style muffins, flat breads, and savoury and sweet breads | 123 | English-style muffins, flat breads, and savory and sweet breads |

| 125 | Pasta and pasta products | 125 | Pasta and pasta products | 124 | Pasta and pasta products | 124 | Pasta and pasta products (without sauce) |

| 127 | Breakfast Cereals, Mixed Source | ||||||

| 128 | Breakfast cereals (hot porridge) | 128 | Bf cereal, hot porridge type | 126 | Breakfast cereal, hot porridge type | 126 | Breakfast cereals, hot porridge style |

| 131 | Sweet biscuits | 131 | Sweet biscuit | 131 | Sweet biscuits | 131 | Sweet biscuits |

| 132 | Savory biscuits | 132 | Savory biscuit | 132 | Savory biscuits | 132 | Savory biscuits |

| 133 | Cake-type desserts | 133 | Cakes, buns, muffins, scones, cake-type desserts | 133 | Cakes, buns, muffins, scones, cake-type desserts | 133 | Cakes, muffins, scones, cake-type desserts |

| 134 | Pastries | 134 | Pastries | 134 | Pastries | 134 | Pastries |

| 135 | Cereal-based dishes | 135 | Mixed dishes where cereal is the major ingredient | 135 | Mixed dishes where cereal is the major ingredient | 135 | Mixed dishes where cereal is the major ingredient |

| 136 | Batter-based products | 136 | Batter-based products | 136 | Batter-based products | 136 | Batter-based products |

| 141 | Butters | 141 | Dairy fats | 141 | Butters | 141 | Butters |

| 142 | Dairy blends | 142 | Dairy blends | ||||

| 142 | Margarine and table spreads | 142 | Margarine | 143 | Margarine and table spreads | 143 | Margarine and table spreads |

| 143 | Vegetable oils | 143 | Vegetable oil | 144 | Vegetable/nut oil | 144 | Plant oils |

| 144 | Other fats | 144 | Other fats | 145 | Other fats | 145 | Other fats |

| 145 | Unspecified fats | 145 | Unspecified fats | 146 | Unspecified fats | 146 | Unspecified fats |

| 151 | Fin fish (excluding canned) | 151 | Fin fish (excluding canned) | 151 | Fin fish (excluding commercially sterile) | 151 | Fin fish (excluding commercially sterile) |

| 152 | Crustacea and molluscs (excluding canned) | 152 | Crustacea and molluscs (excluding canned) | 152 | Crustacea and molluscs (excluding commercially sterile) | 152 | Crustacea and molluscs (excluding commercially sterile) |

| 153 | Other sea and freshwater foods | 153 | Other sea and freshwater foods | 153 | Other sea and freshwater foods | 153 | Other sea and freshwater foods |

| 154 | Packed (canned and bottled) fish and seafood | 154 | Packed (canned and bottled) fish and seafood | 154 | Packed (commercially sterile) fish and seafood | 154 | Packed (commercially sterile) fish and seafood |

| 155 | Fish and seafood products | 155 | Fish and seafood products | 155 | Fish and seafood products (homemade and takeaway) | 155 | Fish and seafood products (homemade and takeaway) |

| 156 | Mixed dishes with fish or seafood as the major component | 156 | Mixed dishes with fish or seafood as the major component | 156 | Mixed dishes with fish or seafood as the major component | 156 | Mixed dishes with fish or seafood as the major component |

| 161 | Pome fruit | 161 | Pome fruit | 161 | Pome fruit | 161 | Pome fruit |

| 162 | Berry fruit | 162 | Berry fruit | 162 | Berry fruit | 162 | Berry fruit |

| 163 | Citrus fruit | 163 | Citrus fruit | 163 | Citrus fruit | 163 | Citrus fruit |

| 164 | Stone fruit | 164 | Stone fruit | 164 | Stone fruit | 164 | Stone fruit |

| 165 | Tropical fruit | 165 | Tropical fruit | 165 | Tropical fruit | 165 | Tropical and subtropical fruit |

| 166 | Other fruit | 166 | Other fruit | 166 | Other fruit | 166 | Other fruit |

| 167 | Fruit combinations | 167 | Mixtures of two or more groups of fruit | 167 | Mixtures of two or more groups of fruit | 167 | Mixtures of two or more groups of fruit |

| 168 | Dried fruits | 168 | Dried fruit, preserved fruit | 168 | Dried fruit, preserved fruit | 168 | Dried fruit, preserved fruit |

| 169 | Fruit dishes | 169 | Mixed dishes where fruit is the major component | 169 | Mixed dishes where fruit is the major component | 169 | Mixed dishes where fruit is the major component |

| 171 | Eggs | 171 | Eggs | 171 | Eggs | 171 | Eggs |

| 173 | Egg substitutes and dishes | ||||||

| 172 | Egg-based dishes | 172 | Dishes where egg is the major ingredient | 172 | Dishes where egg is the major ingredient | 172 | Dishes where egg is the major ingredient |

| 181 | Muscle meat | 181 | Muscle meat | 181 | Muscle meat | 181 | Beef, sheep and pork, unprocessed |

| 182 | Game and other carcase meats | 182 | Game and other carcase meats | 182 | Game and other carcase meats | 182 | Mammalian game meats |

| 183 | Poultry and feathered game | 183 | Poultry and feathered game | 183 | Poultry and feathered game | 183 | Poultry and feathered game |

| 184 | Organ meats and offal, products and dishes | 184 | Organ meats and offal, products and dishes | 184 | Organ meats and offal, products and dishes | 184 | Organ meats and offal, products and dishes |

| 185 | Sausages, frankfurts and saveloys | 185 | Sausages, frankfurts and saveloys | 185 | Sausages, frankfurts and saveloys | 185 | Sausages, frankfurts and saveloys |

| 186 | Processed meat | 186 | Processed meat | 186 | Processed meat | 186 | Processed meat |

| 187 | Mixed dishes where beef or veal is the major component | 187 | Mixed dishes where beef or veal is the major component | 187 | Mixed dishes where beef, veal or lamb is the major component | 187 | Mixed dishes where beef, sheep, pork or mammalian game is the major component |

| 188 | Mixed dishes where lamb or pork, bacon, ham is the major component | 188 | Mixed dishes where lamb or pork, bacon, ham is the major component | 188 | Mixed dishes where pork, bacon, ham is the major component | 188 | Mixed dishes where sausage, bacon, ham or other processed meat is the major component |

| 189 | Mixed dishes where poultry or game is the major component | 189 | Mixed dishes where poultry or game is the major component | 189 | Mixed dishes where poultry or game is the major component | 189 | Mixed dishes where poultry or feathered game is the major component |

| 191 | Dairy milk | 191 | Dairy milk | 191 | Dairy milk (cow, sheep and goat) | 191 | Dairy milk (cow, sheep and goat) |

| 192 | Yogurt | 192 | Yogurt | 192 | Yoghurt | 192 | Yoghurt |

| 193 | Cream | 193 | Cream | 193 | Cream | 193 | Cream |

| 194 | Cheese | 194 | Cheese | 194 | Cheese | 194 | Cheese |

| 195 | Frozen milk products | 195 | Frozen milk products | 195 | Frozen milk products | 195 | Frozen milk products |

| 196 | Milk and milk products based dishes | 196 | Other dishes where milk or a milk product is the major component | 196 | Custards | 196 | Custards |

| 197 | Other dishes where milk or a milk product is the major component | 197 | Other dishes where milk or a milk product is the major component | ||||

| 197 | Milk substitutes | 197 | Milk substitutes | 201 | Dairy milk substitutes, unflavored | 201 | Dairy milk substitutes, unflavored |

| 202 | Dairy milk substitutes, flavored | 202 | Dairy milk substitutes, flavored | ||||

| 203 | Cheese substitute | 203 | Cheese substitute | ||||

| 204 | Soy-based ice confection | 204 | Soy-based ice confection | ||||

| 205 | Soy-based yoghurts | 205 | Soy-based yoghurts | ||||

| 198 | Flavored milks | 198 | Flavored milks | 198 | Flavored milks | 198 | Flavored milks and milkshakes |

| 201 | Soup | 201 | Soup | 211 | Soup (prepared, ready to eat) | 211 | Soup, homemade from basic ingredients |

| 213 | Soup, prepared from dry soup mix | ||||||

| 202 | Dry soup mix | 202 | Dry soup mix | 212 | Dry soup mix | 212 | Dry soup mix |

| 203 | Canned condensed soup | 203 | Canned condensed soup | 213 | Canned condensed soup (unprepared) | 214 | Canned condensed soup (unprepared) |

| 215 | Soup, commercially sterile, prepared from condensed or sold ready to eat | ||||||

| 216 | Soup, not commercially sterile, purchased ready to eat | ||||||

| 211 | Seeds and seed products | 211 | Seeds and seed products | 221 | Seeds and seed products | 221 | Seeds and seed products |

| 212 | Nuts and nuts products | 212 | Nuts and nuts products | 222 | Nuts and nut products | 222 | Nuts and nut products |

| 221 | Gravies and savoury sauces | 221 | Gravies and savoury sauces | 231 | Gravies and savoury sauces | 231 | Gravies and savoury sauces |

| 235 | Dips | ||||||

| 222 | Pickles, chutneys and relishes | 222 | Pickles, chutneys and relishes | 232 | Pickles, chutneys and relishes | 232 | Pickles, chutneys and relishes |

| 224 | Salad dressings | 224 | Salad dressings | 233 | Salad dressings | 233 | Salad dressings |

| 225 | Stuffings | 225 | Stuffings | 234 | Stuffings | 234 | Stuffings |

| 231 | Potatoes | 231 | Potatoes | 241 | Potatoes | 241 | Potatoes |

| 232 | Cabbage, cauliflower and similar brassica vegetables | 232 | Cabbage, cauliflower and similar brassica vegetables | 242 | Cabbage, cauliflower and similar brassica vegetables | 242 | Cabbage, cauliflower and similar brassica vegetables |

| 233 | Carrot and similar root vegetables | 233 | Carrot and similar root vegetables | 243 | Carrot and similar root vegetables | 243 | Carrot and similar root vegetables |

| 234 | Leaf and stalk vegetables | 234 | Leaf and stalk vegetables | 244 | Leaf and stalk vegetables | 244 | Leaf and stalk vegetables |

| 235 | Peas and beans | 235 | Peas and beans | 245 | Peas and beans | 245 | Peas and beans |

| 236 | Tomato and tomato products | 236 | Tomato and tomato products | 246 | Tomato and tomato products | 246 | Tomato and tomato products |

| 237 | Other fruiting vegetables | 237 | Other fruiting vegetables | 247 | Other fruiting vegetables | 247 | Other fruiting vegetables |

| 238 | Other vegetables and vegetable combinations | 238 | Other vegetables and vegetable combinations | 248 | Other vegetables and vegetable combinations | 248 | Other vegetables and vegetable combinations |

| 239 | Dishes where vegetable is the major component | 239 | Dishes where vegetable is the major component | 249 | Dishes where vegetable is the major component | 249 | Dishes where vegetable is the major component |

| 241 | Mature legumes and pulses | 241 | Mature legumes and pulses | 251 | Mature legumes and pulses | 251 | Mature legumes and pulses |

| 242 | Mature legume and pulse products and dishes | 242 | Mature legume and pulse products and dishes | 252 | Mature legume and pulse products and dishes | 206 | Meat substitutes |

| 207 | Dishes where meat substitutes are the major component | ||||||

| 252 | Mature legume and pulse products and dishes | ||||||

| 251 | Potato snacks | 251 | Potato snacks | 261 | Potato snacks | 261 | Potato snacks |

| 252 | Corn snacks | 252 | Corn snacks | 262 | Corn snacks | 262 | Corn snacks |

| 253 | Extruded snacks | 253 | Extruded snacks | 263 | Extruded or reformed snacks | 263 | Extruded or reformed snacks |

| 254 | Pretzels and other snacks | 254 | Pretzels and other snacks | 264 | Pretzels | 264 | Other snacks |

| 265 | Other snacks | ||||||

| 261 | Sugar, honey and syrups | 261 | Sugar, honey and syrups | 271 | Sugar, honey and syrups | 271 | Sugar, honey and syrups |

| 262 | Jam and lemon spreads, chocolate spreads | 262 | Jam and lemon spreads, chocolate spreads | 272 | Jam and lemon spreads, chocolate spreads, sauces | 272 | Jam and lemon spreads, chocolate spreads, sauces |

| 263 | Dishes and products other than confectionery where sugar is the major component | 263 | Dishes and products other than confectionery where sugar is the major component | 273 | Dishes & products other than confectionery where sugar is major component | 273 | Dishes and products other than confectionery where sugar is the major component |

| 271 | Chocolate and chocolate-based confectionery | 271 | Chocolate and chocolate-based confectionery | 281 | Chocolate and chocolate-based confectionery | 281 | Chocolate and chocolate-based confectionery |

| 272 | Cereal-, fruit-, nut-, and seed-bars | 272 | Cereal-, fruit-, nut-, and seed-bars | 282 | Cereal-, fruit-, nut- and seed-bars | 282 | Fruit, nut and seed-bars |

| 283 | Muesli or cereal style bars | ||||||

| 273 | Other confectionery | 273 | Other confectionery | 283 | Other confectionery | 284 | Other confectionery |

| 281 | Beers | 281 | Beers | 291 | Beers | 291 | Beers |

| 282 | Wines | 282 | Wines | 292 | Wines | 292 | Wines |

| 283 | Spirits | 283 | Spirits | 293 | Spirits | 293 | Spirits |

| 284 | Other alcoholic beverages | 284 | Other alcoholic beverages | 294 | Other alcoholic beverages | 294 | Cider and perry |

| 295 | Pre-mixed drinks | 295 | Other alcoholic beverages | ||||

| 291 | Formula dietary foods | 291 | Formula dietary foods | 301 | Formula dietary foods | 301 | Formula dietary foods |

| 292 | Enteral formula | 302 | Enteral formula | ||||

| 302 | Yeast: yeast, vegetable and meat extracts | 302 | Yeast: yeast, vegetable and meat extracts | 311 | Yeast, yeast, vegetable and meat extracts | 311 | Yeast, and yeast vegetable or meat extracts |

| 303 | Artificial sweetening agents | 303 | Artificial sweetening agents | 312 | Intense sweetening agents | 312 | Intense sweetening agents |

| 304 | Herbs, spices, seasonings and stock cubes | 304 | Herbs, spices, seasonings and stock cubes | 313 | Herbs, spices, seasonings and stock cubes | 313 | Herbs, spices, seasonings and stock cubes |

| 305 | Essences | 314 | Essences | 314 | Essences | ||

| 306 | Chemical raising agents and cooking ingredients | 306 | Chemical raising agents and cooking ingredients | 315 | Chemical raising agents and cooking ingredients | 315 | Chemical raising agents and cooking ingredients |

| 311 | Infant formulae and human breast milk | 311 | Infant formulae and human breast milk | 321 | Infant formulae and human breast milk | 321 | Infant formulae and human breast milk |

| 312 | Infant cereal products | 312 | Infant cereal products | 322 | Infant cereal products | 322 | Infant cereal products |

| 313 | Infant foods | 313 | Infant foods | 323 | Infant foods | 323 | Infant foods |

| 314 | Infant drinks | 314 | Infant drinks | 324 | Infant drinks | 324 | Infant drinks |

Table A2.

Per capita mean ± SD comparison of the highest contributors to glycemic load in the three surveys—all subjects included.

| Food Groups | 1995NS | 2007NS | 2012NS | β ± SE | R2 | ptrend 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Mean ± SD | Rank | Mean ± SD | Rank | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Bread and bread rolls | 1 | 18.3 ± 14.0 | 1 | 15.6 ± 13.6 2 | 1 | 15.4 ± 13.9 2 | −0.199 ± 0.000 | 0.964 | <0.001 |

| Fruit and vegetable juices | 2 | 10.0 ± 10.8 | 3 | 6.5 ± 8.5 2 | 4 | 5.8 ± 8.6 2 | −0.277 ± 0.000 | 0.992 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 3 | 9.1 ± 10.7 | 2 | 9.1 ± 11.4 | 3 | 7.0 ± 10.0 2,3 | −0.084 ± 0.001 | 0.332 | <0.001 |

| Potatoes | 4 | 7.5 ± 10.7 | 4 | 5.7 ± 9.1 2 | 6 | 4.3 ± 8.7 2,3 | −0.181 ± 0.000 | 0.950 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened beverages | 5 | 5.9 ± 10.4 | 7 | 3.9 ± 7.7 2 | 7 | 4.0 ± 9.0 2 | −0.132 ± 0.000 | 0.890 | <0.001 |

| Cereal based dishes | 6 | 3.9 ± 9.1 | 9 | 3.6 ± 8.6 | 2 | 9.8 ± 15.0 2,3 | 0.229 ± 0.004 | 0.287 | <0.001 |

| Cake-type dessert | 7 | 3.2 ± 7.8 | 10 | 3.0 ± 7.3 | 8 | 3.9 ± 9.5 3 | 0.023 ± 0.001 | 0.167 | <0.001 |

| Flours, cereals and starches | 8 | 3.1 ± 9.8 | 6 | 4.1 ± 11.0 2 | 5 | 4.6 ± 12.2 2 | 0.088 ± 0.000 | 0.995 | <0.001 |

| Dairy milk | 9 | 3.1 ± 3.6 | 8 | 3.8 ± 4.2 2 | 10 | 3.1 ± 4.2 3 | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 0.126 | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuits | 10 | 2.8 ± 5.3 | 12 | 2.7 ± 5.6 | 9 | 3.2 ± 6.4 3 | 0.015 ± 0.000 | 0.161 | <0.001 |

| Frozen milk products | 11 | 2.4 ± 4.7 | 21 | 1.6 ± 3.7 2 | 20 | 1.5 ± 3.6 2 | −0.060 ± 0.000 | 0.972 | <0.001 |

| Pastas | 12 | 2.2 ± 6.2 | 5 | 4.2 ± 8.7 2 | 17 | 1.8 ± 6.3 3 | 0.044 ± 0.002 | 0.059 | <0.001 |

| Sugar, honey and syrups | 13 | 2.1 ± 3.8 | 19 | 1.8 ± 3.8 | 18 | 1.6 ± 3.8 2 | −0.027 ± 0.000 | 0.911 | <0.001 |

| Pome fruit | 14 | 2.0 ± 3.6 | 15 | 2.3 ± 3.9 | 12 | 2.7 ± 4.3 2,3 | 0.035 ± 0.000 | 0.810 | <0.001 |

| Pastries | 15 | 1.9 ± 5.3 | 17 | 2.0 ± 5.7 | 16 | 1.8 ± 5.5 | −0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| Other confectionery | 16 | 1.9 ± 5.7 | 14 | 2.5 ± 7.3 2 | 22 | 1.2 ± 3.9 3 | −0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| Chocolates | 17 | 1.7 ± 4.2 | 16 | 2.1 ± 5.5 | 21 | 1.5 ± 4.5 3 | 0.002 ± 0.000 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Savory biscuits | 18 | 1.5 ± 4.2 | 13 | 2.6 ± 5.9 2 | 11 | 3.0 ± 7.2 2 | 0.093 ± 0.000 | 0.999 | <0.001 |

| Tropical and subtropical fruit | 19 | 1.4 ± 3.6 | 18 | 1.9 ± 4.3 2 | 14 | 1.9 ± 4.5 2 | 0.038 ± 0.000 | 0.925 | <0.001 |

| Fancy breads | 20 | 1.3 ± 4.7 | 11 | 2.8 ± 7.3 2 | 13 | 2.6 ± 7.5 2 | 0.095 ± 0.000 | 0.871 | <0.001 |

| Potato snacks | 21 | 1.1 ± 3.0 | 25 | 1.2 ± 3.6 | 23 | 1.2 ± 3.9 | 0.006 ± 0.000 | 0.929 | <0.001 |

| Batter-based product | 22 | 1.0 ± 4.5 | 20 | 1.7 ± 5.7 2 | 28 | 0.9 ± 4.0 3 | 0.015 ± 0.001 | 0.068 | <0.001 |

| Confectionery based dishes | 23 | 1.0 ± 3.5 | 28 | 0.8 ± 3.1 | 26 | 1.0 ± 3.4 | −0.007 ± 0.000 | 0.162 | <0.001 |

| Cereal-, fruit-, nut-,seed-bars | 24 | 1.0 ± 2.6 | 22 | 1.3 ± 3.9 2 | 15 | 1.9 ± 4.7 2,3 | 0.048 ± 0.000 | 0.804 | <0.001 |

| Extruded snacks | 25 | 0.8 ± 3.5 | 43 | 0.2 ± 1.7 2 | 34 | 0.5 ± 3.0 2,3 | −0.031 ± 0.000 | 0.538 | <0.001 |

| Milk and milk products based dishes | 26 | 0.8 ± 2.7 | 36 | 0.5 ± 2.3 2 | 39 | 0.4 ± 2.1 2 | −0.025 ± 0.000 | 0.994 | <0.001 |

| Gravies and savory sauces | 27 | 0.6 ± 1.3 | 27 | 0.8 ± 1.8 2 | 33 | 0.6 ± 2.0 3 | 0.006 ± 0.000 | 0.098 | <0.001 |

| Poultry based dishes | 28 | 0.6 ± 2.2 | 33 | 0.6 ± 2.2 | 19 | 1.5 ± 4.9 2,3 | 0.038 ± 0.001 | 0.341 | <0.001 |

1 Ptrend from linear regression test for trends in means of the three surveys. 2 p < 0.001 compared with 1995NS. 3 p < 0.001 compared with 2007NS.

Table A3.

Per consumer mean ± SD comparison of the highest contributors to glycemic load in the three surveys—all subjects included.

| Food Groups | 1995NS | 2007NS | 2012NS | β ± SE | R2 | Ptrend 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Mean ± SD | % 1 | Rank | Mean ± SD | % 1 | Rank | Mean ± SD | % 1 | ||||

| Flour, cereals and starches | 1 | 23.0 ± 15.7 | 13.7 | 1 | 22.6 ± 15.8 | 18.3 | 1 | 27.1 ± 16.6 4 | 16.9 | 0.144 ± 0.009 | 0.138 | <0.001 |

| Bread and bread rolls | 2 | 21.8 ± 12.6 | 84.2 | 2 | 20.5 ± 12.0 3 | 76.4 | 3 | 21.2 ± 12.0 | 72.5 | −0.038 ± 0.001 | 0.126 | <0.001 |

| Cereal-based dishes | 3 | 16.5 ± 11.8 | 23.7 | 6 | 16.0 ± 11.4 | 22.6 | 2 | 24.1 ± 14.5 3,4 | 40.8 | 0.431 ± 0.010 | 0.395 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (hot porridge) | 4 | 16.1 ± 8.3 | 2.7 | 3 | 18.2 ± 13.0 | 3.3 | 8 | 15.3 ± 10.8 | 5.3 | −0.050 ± 0.006 | 0.145 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 5 | 16.0 ± 9.4 | 56.6 | 4 | 17.3 ± 10.2 3 | 52.3 | 7 | 15.9 ± 9.3 4 | 43.9 | 0.046 ± 0.001 | 0.193 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened beverages | 6 | 15.5 ± 11.8 | 37.8 | 11 | 12.4 ± 9.3 3 | 31.4 | 18 | 10.9 ± 12.0 3 | 36.9 | −0.258 ± 0.001 | 0.919 | <0.001 |

| Potatoes | 7 | 14.9 ± 10.8 | 50.2 | 9 | 13.4 ± 9.5 3 | 42.5 | 10 | 12.9 ± 10.6 3 | 33.7 | −0.157 ± 0.000 | 0.996 | <0.001 |

| Batter-based products | 8 | 14.5 ± 9.7 | 7.0 | 10 | 13.2 ± 10.3 | 12.5 | 11 | 12.7 ± 8.6 | 7.2 | −0.125 ± 0.000 | 0.986 | <0.001 |

| Cake-type desserts | 9 | 14.3 ± 10.8 | 22.2 | 8 | 14.2 ± 9.8 | 21.1 | 4 | 19.1 ± 12.6 3,4 | 20.2 | 0.204 ± 0.007 | 0.278 | <0.001 |

| Fruit and vegetable juices | 10 | 14.2 ± 10.3 | 70.7 | 14 | 11.1 ± 8.5 3 | 58.4 | 16 | 11.6 ± 8.1 3 | 39.8 | −0.180 ± 0.001 | 0.807 | <0.001 |

| Pastas | 11 | 14.1 ± 9.2 | 15.3 | 5 | 16.0 ± 9.9 | 26.2 | 5 | 17.7 ± 10.6 3 | 10.0 | 0.128 ± 0.000 | 0.998 | <0.001 |

| Fancy breads | 12 | 13.1 ± 7.8 | 10.1 | 7 | 15.3 ± 10.1 | 18.0 | 6 | 17.6 ± 10.7 3,4 | 14.8 | 0.204 ± 0.005 | 0.548 | <0.001 |

| Pastries | 13 | 10.8 ± 8.1 | 17.6 | 12 | 12.1 ± 8.4 | 16.7 | 12 | 12.7 ± 8.9 | 14.0 | 0.168 ± 0.000 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Extruded snacks | 14 | 9.9 ± 7.4 | 8.6 | 18 | 8.9 ± 6.4 | 2.5 | 17 | 11.1 ± 8.5 | 4.7 | 0.037 ± 0.005 | 0.101 | <0.001 |

| Other confectionery | 15 | 8.8 ± 9.5 | 21.3 | 13 | 12.1 ± 11.8 3 | 21.1 | 34 | 7.0 ± 6.7 4 | 17.7 | 0.100 ± 0.005 | 0.162 | <0.001 |

| Dried fruit, preserved fruit | 16 | 8.8 ± 8.3 | 4.8 | 19 | 8.8 ± 8.1 | 6.7 | 20 | 9.7 ± 8.1 | 4.9 | 0.041 ± 0.002 | 0.377 | <0.001 |

| Pretzels and other snacks | 17 | 8.4 ± 10.8 | 0.7 | 36 | 6.3 ± 5.7 | 5.2 | 37 | 6.9 ± 6.7 | 4.9 | −0.094 ± 0.002 | 0.813 | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuit | 18 | 8.2 ± 6.2 | 34.1 | 20 | 8.7 ± 7.0 | 30.5 | 21 | 9.6 ± 7.8 3 | 33.7 | 0.061 ± 0.001 | 0.728 | <0.001 |

| Confectionery-based dishes | 19 | 8.0 ± 6.7 | 12.4 | 23 | 8.4 ± 6.8 | 9.0 | 26 | 8.3 ± 6.3 | 11.7 | 0.064 ± 0.000 | 0.997 | <0.001 |

| Savory biscuit | 20 | 7.6 ± 6.3 | 20.2 | 16 | 9.9 ± 7.6 3 | 26.5 | 15 | 11.7 ± 9.8 3,4 | 26.0 | 0.187 ± 0.001 | 0.953 | <0.001 |

| Frozen milk products | 21 | 7.5 ± 5.5 | 31.8 | 34 | 6.5 ± 5.0 3 | 24.3 | 36 | 6.9 ± 4.8 | 21.5 | −0.043 ± 0.001 | 0.462 | <0.001 |

| Tropical and subtropical fruit | 22 | 7.3 ± 5.0 | 19.1 | 27 | 8.1 ± 5.2 | 23.9 | 23 | 9.1 ± 5.4 3 | 21.4 | 0.086 ± 0.000 | 0.998 | <0.001 |

| Milk and milk products based dishes | 23 | 6.9 ± 4.7 | 11.5 | 29 | 8.1 ± 5.0 | 6.3 | 30 | 7.3 ± 5.7 | 5.2 | 0.056 ± 0.004 | 0.194 | <0.001 |

| Fruit dishes | 24 | 6.9 ± 3.7 | 0.5 | 15 | 10.9 ± 7.1 | 0.4 | 35 | 6.9 ± 8.5 | 0.5 | -0.069 ± 0.055 | 0.038 | 0.217 |

| Infant formulae / breast milk | # | 6.7 ± 15.8 | 0.0 | 24 | 8.4 ± 8.7 | 0.6 | 9 | 15.3 ± 15.6 | 0.5 | 0.113 ± 0.058 | 0.292 | 0.057 |

| Chocolates | 25 | 6.4 ± 6.1 | 26.5 | 22 | 8.4 ± 8.4 3 | 24.7 | 27 | 7.7 ± 7.5 | 19.0 | 0.061 ± 0.000 | 0.891 | <0.001 |

| Fruit combinations | 26 | 6.4 ± 6.4 | 2.5 | 28 | 8.1 ± 5.5 | 3.0 | 22 | 9.6 ± 7.3 | 3.3 | 0.200 ± 0.001 | 0.988 | <0.001 |

| Flavored milks | 27 | 6.4 ± 4.2 | 6.5 | 32 | 7.6 ± 4.3 | 8.1 | 14 | 12.7 ± 9.0 3,4 | 8.5 | 0.246 ± 0.007 | 0.649 | <0.001 |

| Potato snacks | 28 | 6.1 ± 4.3 | 18.4 | 33 | 7.1 ± 6.1 | 16.7 | 32 | 7.1 ± 6.6 | 17.2 | 0.021 ± 0.000 | 0.935 | <0.001 |

| Infant foods | 29 | 6.1 ± 5.8 | 0.6 | 35 | 6.4 ± 5.0 | 0.4 | # | 9.3 ± 7.2 | 0.2 | 0.081 ± 0.005 | 0.878 | <0.001 |

| Cereal-, fruit-, nut-, and seed-bars | 30 | 6.0 ± 3.6 | 15.9 | 17 | 9.4 ± 5.7 3 | 14.2 | 19 | 10.6 ± 5.5 3,4 | 17.7 | 0.243 ± 0.000 | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Fish and seafood products | 31 | 5.8 ± 5.1 | 5.0 | 44 | 3.9 ± 3.0 3 | 5.2 | 31 | 7.2 ± 5.5 4 | 3.7 | 0.028 ± 0.007 | 0.028 | <0.001 |

| Other fruits | 32 | 5.8 ± 6.1 | 9.9 | 30 | 7.9 ± 6.7 3 | 16.1 | 38 | 6.3 ± 5.4 4 | 15.2 | 0.083 ± 0.004 | 0.230 | <0.001 |

| Pome fruits | 33 | 5.7 ± 4.0 | 34.8 | 37 | 6.0 ± 4.1 | 37.9 | 33 | 7.1 ± 4.2 3,4 | 37.2 | 0.053 ± 0.001 | 0.390 | <0.001 |

| Soups | 34 | 5.7 ± 5.9 | 6.1 | 25 | 8.3 ± 6.5 3 | 6.6 | 42 | 5.3 ± 6.2 4 | 5.0 | 0.064 ± 0.008 | 0.101 | <0.001 |

| Legume and legume-based dishes | 35 | 5.5 ± 6.0 | 4.2 | 42 | 4.6 ± 4.5 | 4.7 | 40 | 6.1 ± 6.6 | 3.3 | -0.026 ± 0.003 | 0.201 | <0.001 |

| Vegetable-based dishes | 36 | 5.5 ± 5.7 | 1.6 | 49 | 2.8 ± 6.1 | 7.0 | 56 | 1.5 ± 4.7 3 | 13.4 | -0.251 ± 0.004 | 0.854 | <0.001 |

| Corn snacks | 37 | 5.3 ± 5.7 | 6.5 | 21 | 8.6 ± 7.6 3 | 7.5 | 28 | 7.3 ± 7.8 | 6.8 | 0.102 ± 0.003 | 0.568 | <0.001 |

| Yogurt | 38 | 4.7 ± 4.3 | 8.1 | 41 | 4.8 ± 3.9 | 19.6 | 47 | 4.1 ± 5.1 | 18.2 | -0.048 ± 0.002 | 0.257 | <0.001 |

| Sugar, honey and syrups | 39 | 4.7 ± 4.5 | 45.1 | 39 | 5.1 ± 4.8 | 36.0 | 39 | 6.2 ± 5.3 3,4 | 26.3 | 0.058 ± 0.001 | 0.598 | <0.001 |

| Fish and seafood based dishes | 40 | 4.5 ± 4.0 | 2.3 | 51 | 2.1 ± 2.4 | 0.4 | 24 | 8.8 ± 11.2 | 1.1 | 0.059 ± 0.022 | 0.062 | 0.010 |

| Canned condensed soup | # | 4.4 ± 5.7 | 0.1 | 45 | 3.9 ± 4.6 | 0.4 | 13 | 12.7 ± 8.6 | 0.4 | 0.762 ± 0.205 | 0.310 | <0.001 |

Post-hoc analysis was not performed for food group with any group having less than 2 consumers (infant foods and infant formulae/breast milk). Groups with less than 10 consumers were excluded from the ranking (marked with #). 1 Percentage of participants who consumed foods in the food group; 2 Ptrend from linear regression test for trends in medians of the three surveys; 3 p < 0.001 compared with 1995NS; 4 p < 0.001 compared with 2007NS.

Table A4.

The contribution of the top 20 GL food groups to inter-individual variations in dietary glycaemic index (dGI) and glycaemic load (dGL) in 1995NS (n = 2658, all subjects included).

| Food Groups | dGI | dGL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value | β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value | |

| Model R2 = 0.433 | Model R2 = 0.912 | |||||

| Bread and bread rolls | 2.03 ± 0.13 | 0.082 | <0.001 | 17.23 ± 0.69 | 0.191 | <0.001 |

| Fruit and vegetable juices | −0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.014 | <0.001 | 3.21 ± 0.12 | 0.218 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 3.01 ± 0.22 | 0.066 | <0.001 | 32.73 ± 1.15 | 0.234 | <0.001 |

| Potatoes | 1.62 ± 0.08 | 0.133 | <0.001 | 6.64 ± 0.42 | 0.086 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened beverages | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.026 | <0.001 | 4.20 ± 0.15 | 0.227 | <0.001 |

| Cereal based dishes | 0.34 ± 0.07 | 0.009 | <0.001 | 3.96 ± 0.37 | 0.042 | <0.001 |

| Cake-type dessert | −0.30 ± 0.15 | 0.002 | 0.045 | 9.93 ± 0.78 | 0.058 | <0.001 |

| Flours, cereals and starches | 1.06 ± 0.09 | 0.053 | <0.001 | 10.67 ± 0.45 | 0.173 | <0.001 |

| Dairy milk | −0.44 ± 0.03 | 0.079 | <0.001 | −1.03 ± 0.15 | 0.017 | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuits | 0.10 ± 0.34 | <0.001 | 0.776 | 9.23 ± 1.78 | 0.010 | <0.001 |

| Frozen milk products | −0.77 ± 0.09 | 0.026 | <0.001 | 1.52 ± 0.48 | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| Pastas | −0.93 ± 0.09 | 0.036 | <0.001 | 2.45 ± 0.49 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| Sugar, honey and syrups | 1.75 ± 0.48 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 28.88 ± 2.51 | 0.048 | <0.001 |

| Pome fruit | −0.93 ± 0.07 | 0.058 | <0.001 | 1.51 ± 0.38 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| Pastries | −0.42 ± 0.11 | 0.006 | <0.001 | −0.12 ± 0.56 | <0.001 | 0.830 |

| Other confectionery | 3.96 ± 0.39 | 0.039 | <0.001 | 46.65 ± 2.01 | 0.169 | <0.001 |

| Chocolates | −1.56 ± 0.30 | 0.010 | <0.001 | 4.03 ± 1.58 | 0.002 | 0.011 |

| Savory biscuits | 2.30 ± 0.48 | 0.009 | <0.001 | 13.79 ± 2.50 | 0.011 | <0.001 |

| Tropical and subtropical fruit | −0.70 ± 0.15 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 4.52 ± 0.80 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| Fancy breads | 1.37 ± 0.31 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 12.33 ± 1.62 | 0.022 | <0.001 |

β ± SE calculated using multiple linear regression, with energy and the food groups as the predictor variables. β expressed as change in dGI or dGL per 100 g increase in intake of the corresponding food group.

Table A5.

The contribution of the top 20 GL food groups to inter-individual variations in dietary glycaemic index (dGI) and glycaemic load (dGL) in 2007NS (n = 4828, all subjects included).

| Food Groups | dGI | dGL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value | β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value | |

| Model R2 = 0.362 | Model R2 = 0.881 | |||||

| Bread and bread rolls | 2.58 ± 0.12 | 0.084 | <0.001 | 15.88 ± 0.55 | 0.149 | <0.001 |

| Breakfast cereals (ready to eat) | 4.11 ± 0.18 | 0.094 | <0.001 | 35.86 ± 0.82 | 0.284 | <0.001 |

| Fruit and vegetable juices | 0.05 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.113 | 3.12 ± 0.14 | 0.093 | <0.001 |

| Potatoes | 1.79 ± 0.08 | 0.092 | <0.001 | 7.74 ± 0.36 | 0.087 | <0.001 |

| Pastas | −0.55 ± 0.06 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 5.01 ± 0.29 | 0.060 | <0.001 |

| Flours, cereals and starches | 1.65 ± 0.08 | 0.089 | <0.001 | 13.60 ± 0.34 | 0.249 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened beverages | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 2.91 ± 0.12 | 0.115 | <0.001 |

| Dairy milk | −0.36 ± 0.03 | 0.034 | <0.001 | −0.61 ± 0.12 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| Cereal based dishes | −0.01 ± 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.819 | 3.91 ± 0.27 | 0.042 | <0.001 |

| Cake-type dessert | 0.07 ± 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.643 | 8.65 ± 0.69 | 0.031 | <0.001 |

| Fancy breads | 1.60 ± 0.20 | 0.013 | <0.001 | 13.96 ± 0.9 | 0.047 | <0.001 |

| Sweet biscuits | 1.56 ± 0.32 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 17.29 ± 1.43 | 0.029 | <0.001 |

| Savory biscuits | 3.92 ± 0.39 | 0.020 | <0.001 | 20.87 ± 1.75 | 0.029 | <0.001 |

| Other confectionery | 5.20 ± 0.26 | 0.075 | <0.001 | 49.42 ± 1.18 | 0.268 | <0.001 |

| Pome fruit | −0.86 ± 0.06 | 0.036 | <0.001 | 2.11 ± 0.29 | 0.011 | <0.001 |

| Chocolates | −0.14 ± 0.26 | <0.001 | 0.595 | 11.97 ± 1.18 | 0.021 | <0.001 |

| Pastries | 0.11 ± 0.10 | <0.001 | 0.264 | 2.67 ± 0.43 | 0.008 | <0.001 |

| Tropical and subtropical fruit | −0.44 ± 0.10 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 3.74 ± 0.46 | 0.014 | <0.001 |

| Sugar, honey and syrups | 2.04 ± 0.46 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 32.06 ± 2.07 | 0.048 | <0.001 |

| Batter-based product | 2.79 ± 0.22 | 0.033 | <0.001 | 16.39 ± 0.97 | 0.056 | <0.001 |

β ± SE calculated using multiple linear regression, with energy and the food groups as the predictor variables. β expressed as change in dGI or dGL per 100 g increase in intake of the corresponding food group.

Table A6.

The contribution of the top 20 GL food groups to inter-individual variations in dietary glycaemic index (dGI) and glycaemic load (dGL) in 2012NS (n = 2374, all subjects included).

| Food Groups | dGI | dGL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value | β ± SE | Partial R2 | p Value | |

| Model R2 = 0.303 | Model R2 = 0.871 | |||||