Abstract

The NITRATE TRANSPORTER 1/PEPTIDE TRANSPORTER family (NPF) proteins play important roles in moving substrates such as nitrate, peptides, amino acids, dicarboxylates, malate, glucosinolates, indole acetic acid (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA), and jasmonic acid. Although a unified nomenclature of NPF members in plants has been reported, this gene family has not been studied as thoroughly in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) as it has in other species. Our objective was to provide general information about apple MdNPFs and analyze the transcriptional responses of some members to different levels of nitrate supplies. We identified 73 of these genes from the apple genome and used phylogenetic analysis to organize them into eight major groups. These apple NPFs are structurally conserved, based on alignment of amino acid sequences and analyses of phylogenetics and conserved domains. Examination of their genomic structures indicated that these genes are highly conserved among other species. We monitored 14 cloned MdNPFs that showed varied expression patterns under different nitrate concentrations and in different tissues. Among them, NPF6.5 was significantly induced by both low and high levels of nitrate. When compared with the wild type, 35S:MdNPF6.5 transgenic apple calli were more tolerant to low-N stress, which demonstrated that this gene confers greater capacity for nitrogen uptake under those conditions. We also analyzed the expression patterns of those 73 genes in various tissues. Our findings benefit future research on this family of genes.

Keywords: apple, NPF gene family, genome-wide, nitrate concentration, expression analysis

1. Introduction

Uptake, transport, and recycling of nutrients are critical processes during the plant life cycle. Nitrogen is a major component of proteins, nucleic acids, cell walls, phospholipids, chlorophyll, hormones, vitamins, enzymes/coenzymes, and alkaloids [1]. A series of pathways, including transporters and ion channels, direct nitrate uptake from the soil, its long-distance transport, source-to-sink allocations, homeostasis, and signal transduction [1,2] have been reported. These nitrate and peptide transporters have important roles in nutrient cycling [3,4,5]. Nitrate is a valuable source of nitrogen (N) for higher plants, especially in arid and semi-arid regions [6,7]. Through various mechanisms, a large part of the nitrate is absorbed from the soil by nitrate transporters (NRTs), e.g., NRT1/PTR, NRT2, and NRT3. When adapting to changing concentrations of soil nitrate, plant roots utilize different systems of absorption, including a low-affinity transport system (LATS, >1 mM) and a high-affinity transport system (HATS, 1 μM–1 mM). Two types of transportation are used—constitutive (cLATS/cHATS) and inducible (iLATS/iHATS)—that are determined by whether gene expression can be induced by a particular soil nitrate concentration [1]. The first discovered NRT member was AtNRT1.1 or CHL1 in Arabidopsis thaliana (hereafter, Arabidopsis). This dual-affinity nitrate transporter has a very wide absorption range for both high and low concentrations of nitrate [8]. It also plays a valuable role in nitrate transport from roots to stems as well as in nitrogen-regulated auxin transport and root morphology [9]. In Arabidopsis, NRT1.5 is a bi-directional transporter that is critical for the influx and efflux of root-to-shoot translocation of nitrate [10]. AtNRT1.6 is mainly responsible for moving nitrate to seeds to support their development [11], while AtNRT1.8 and AtNRT1.9 have roles in long-distance transport and in the xylem-to-phloem process of nitrate-loading [1].

NRT1 belongs to the peptide transporter (PTR) family, members of which are composed of dipeptide and tripeptide transporters that act as proton-dependent oligo peptide transporters (POTs) in plants [12,13,14]. The PTR family can be divided into several groups according to differences in substrates, with some members, such as those within the NRT subfamily, being involved in nitrate transport. All PTRs share a strong conserved sequence and 12 putative transmembrane (TM) regions, including a large hydrophilic loop between TM domains 6 and 7. Members of this PTR family tend to have 450–600 amino acids (aa). Substrate specificity means that members are classified into one of three types: di-/tripeptide transporter, nitrate transporter, or other substrate transporter [15]. The first di-/tripeptide transporter member, AtPTR2, was identified in Arabidopsis, and shows relatively higher expression levels in certain organs and at different developmental stages, e.g., three-day-old germinants, seedling roots, and young leaves [13]. In rice (Oryza sativa; Os), most OsPTR members have three highly conserved motifs [14]. Although located at different chromosomal positions, the AtPTR family members in Arabidopsis also have three conserved motifs [14]. The plant PTR family is thought to have key roles in nitrogen metabolism, tolerance to abiotic stresses, and the seed development. For example, AtPTR3 confers tolerance to NaCl stress and infections by bacterial pathogens [16,17]. Expression of AtPTR5 promotes the accumulation of peptides in pollen, ovules, and developing seeds [18].

Because NRT1 and PTR are related, the unified family—NITRATE TRANSPORTER 1/PEPTIDE TRANSPORTER (NRT1/PTR)—is named NPF, a label now used in the phylogenetic trees of 33 fully sequenced plant genomes [19]. Plant NPF proteins can transport several types of substrates, such as nitrate [15], peptides [14], dicarboxylates [20], glucosinolates [21], indole acetic acid (IAA) [9], abscisic acid (ABA) [22], and gibberellin (GA) [23]. All NPFs in higher plants share high similarity among sequences and contain 12 putative TM regions connected by short peptide loops. In between each group of six TM regions is a large hydrophilic loop. Phylogenetic analysis of NPFs in 33 fully sequenced genomes has shown that this family can be divided into eight well-defined subfamilies.

In Arabidopsis, AtNPF6.2 and AtNPF6.3 play major roles in nitrate uptake at high concentrations and AtNPF6.2 is also a low-affinity nitrate transporter [2]. AtNPF1.1 and AtNPF1.2 are more highly expressed in expanded leaves, where nitrate is transferred between xylem and phloem for optimal distribution [24]. Some sources of stress, including phytohormones ethylene and jasmonate, regulate the expression of AtNPF7.2 and AtNPF7.3, causing nitrate to accumulate in the roots [25]. Both AtNPF2.12 and AtNPF5.5 are critical in the transport of sufficient nitrate to developing seeds [26]. VvNPF3.2 is a pathogen-inducible transporter in Vitis vinifera. Some NPF genes in potato (Solanum tuberosum) are up-regulated when plants are infected by potato virus Y (PVY), which suggests that nutrient transport can enhance plant tolerance to PVY [27,28].

Several family members with highly conserved NPF domains have been identified in many plant species, including Arabidopsis [29,30], rice [31,32], Triticum aestivum [33], poplar (Populus trichocarpa) [34], Lotus japonicas [35], tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) [36], and Catalpa bungei [37]. However, only a few systematic analyses have been conducted for apple NPF genes. Here, we examined their protein and gene structures, conserved domains, phylogenetic relationships, chromosomal locations, and TM regions. We also assessed their expression in various tissues (roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruit) and 14 of them in response to different nitrate concentrations. As the first systematic study of this family in apple, our results will provide a valuable basis for selecting candidate genes to improve the efficiency of nitrogen utilization and further investigating the function of MdNPFs in that fruit crop.

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Annotation of NPF Genes in Apple

To identify the NPF genes in apple, we conducted a Blast P against its genome database. According to the 139 sequences previously identified by Léran et al. [19], 89 NPFs were retained after removing the same sequences or new sequences in the Md3.0 version for genome annotation. From those 89, 16 were then deleted because their sequences were too short or too long (Supplementary Materials, Table S1. The nomenclature of the apple NPF genes followed previously published rules, i.e., the name should be NPFX.Y, where X represents the subfamily and Y stands for the specific member within the subfamily [19]. From this, we summarized details including the chromosome location and ORF of each gene, as well as the protein length, molecular weight, and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) for each protein that an MdNPF encoded (Table 1). Each apple NPF usually encoded 400–600 aa, with molecular weights ranging from 29.89 to 76.60 kDa. The theoretical pI was distributed between 5.26 and 9.62, mainly between 6.00 and 7.00.

Table 1.

Basic information about apple NPFs.

| Gene Name | Gene ID a | Chromosome Location | ORF | Protein Length (aa) | MW (kDa) | Theoretical Isoeletrical Point (pI) | GenBank Accession Numbers of Cloned Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MdNPF1 | MD15G1190800 | Chr15:15008548-15011039 | 1779 | 593 | 65.21 | 8.90 | |

| MdNPF2.1 | MD11G1122200 | Chr11:11243604-11246153 | 1656 | 552 | 60.36 | 8.14 | |

| MdNPF2.2 | MD11G1121600 | Chr11:11225429-11227624 | 1404 | 468 | 51.09 | 8.99 | |

| MdNPF2.3 | MD07G1180500 | Chr07:25970318-25972596 | 1539 | 513 | 56.69 | 9.27 | |

| MdNPF2.4 | MD01G1112600 | Chr01:22682711-22685617 | 1662 | 554 | 60.53 | 9.25 | |

| MdNPF2.5 | MD11G1122500 | Chr11:11284715-11290091 | 1698 | 566 | 61.85 | 8.86 | MG021338 |

| MdNPF2.6 | MD03G1108900 | Chr03:9496734-9500175 | 1812 | 604 | 66.37 | 8.73 | MG021345 |

| MdNPF2.7 | MD03G1108700 | Chr03:9467766-9470916 | 1683 | 561 | 61.53 | 8.96 | |

| MdNPF2.8 | MD06G1186800 | Chr06:32435102-32437373 | 1809 | 603 | 67.17 | 9.61 | |

| MdNPF2.9 | MD14G1193200 | Chr14:28393718-28396166 | 1866 | 622 | 69.34 | 8.88 | |

| MdNPF2.10 | MD04G1137500 | Chr04:22509802-22511767 | 1764 | 588 | 64.55 | 8.76 | |

| MdNPF2.11 | MD14G1193100 | Chr14:28376948-28379737 | 1746 | 482 | 64.43 | 9.00 | MG021332 |

| MdNPF2.12 | MD06G1186500 | Chr06:32427308-32429277 | 1299 | 433 | 48.04 | 8.86 | |

| MdNPF2.13 | MD16G1080100 | Chr16:5611393-5619434 | 1845 | 615 | 68.20 | 8.44 | |

| MdNPF2.14 | MD16G1079900 | Chr16:5602664-5605755 | 1818 | 606 | 66.73 | 8.14 | |

| MdNPF2.15 | MD16G1080000 | Chr16:5608051-5610469 | 1737 | 579 | 63.71 | 7.82 | |

| MdNPF3.1 | MD13G1043200 | Chr13:3030935-3034949 | 1740 | 580 | 64.10 | 8.61 | MG021337 |

| MdNPF3.2 | MD13G1043100 | Chr13:3013976-3017053 | 1776 | 592 | 65.47 | 8.61 | |

| MdNPF3.3 | MD16G1044000 | Chr16:3127680-3131016 | 1743 | 581 | 64.24 | 8.34 | |

| MdNPF4.1 | MD05G1164400 | Chr05:29316397-29322734 | 1308 | 436 | 48.37 | 7.39 | |

| MdNPF4.2 | MD10G1153900 | Chr10:24150970-24153718 | 1605 | 535 | 59.31 | 9.33 | |

| MdNPF4.3 | MD10G1154000 | Chr10:24171779-24174663 | 1602 | 534 | 59.02 | 8.26 | |

| MdNPF4.4 | MD08G1248200 | Chr08:31226687-31231330 | 1842 | 614 | 67.84 | 8.30 | MG021342 |

| MdNPF4.5 | MD15G1443100 | Chr15:54322869-54325021 | 1482 | 494 | 54.88 | 8.96 | |

| MdNPF4.6 | MD05G1000900 | Chr05:293868-298577 | 1845 | 615 | 68.08 | 8.54 | |

| MdNPF4.7 | MD13G1079300 | Chr13:5562578-5567885 | 1761 | 587 | 64.77 | 8.58 | |

| MdNPF4.8 | MD16G1079100 | Chr16:5547983-5553360 | 1761 | 587 | 64.85 | 8.70 | |

| MdNPF4.9 | MD14G1194100 | Chr14:28528146-28530941 | 1758 | 586 | 64.70 | 8.26 | |

| MdNPF4.10 | MD08G1040500 | Chr08:2990042-2993173 | 1668 | 556 | 61.30 | 8.22 | |

| MdNPF4.11 | MD04G1184500 | Chr04:27539356-27541647 | 1836 | 612 | 68.06 | 9.15 | |

| MdNPF4.12 | MD12G1197700 | Chr12:27888187-27890493 | 1653 | 551 | 61.38 | 8.67 | |

| MdNPF4.13 | MD10G1271800 | Chr10:36356975-36363499 | 1779 | 593 | 66.11 | 8.08 | |

| MdNPF4.14 | MD05G1293900 | Chr05:42659455-42665121 | 1809 | 603 | 67.05 | 8.58 | |

| MdNPF5.1 | MD07G1230600 | Chr07:30498119-30501840 | 1776 | 592 | 66.07 | 8.76 | MG021340 |

| MdNPF5.2 | MD05G1192100 | Chr05:32036536-32040692 | 1809 | 603 | 67.23 | 9.30 | |

| MdNPF5.3 | MD16G1224200 | Chr16:22556239-22559806 | 1644 | 548 | 61.45 | 8.57 | |

| MdNPF5.4 | MD13G1218900 | Chr13:21148526-21157623 | 1806 | 602 | 67.12 | 9.36 | |

| MdNPF5.5 | MD05G1342600 | Chr05:46297101-46299829 | 1779 | 593 | 66.26 | 9.22 | |

| MdNPF5.6 | MD07G1039100 | Chr07:3293256-3295279 | 873 | 291 | 32.36 | 9.39 | |

| MdNPF5.7 | MD07G1038900 | Chr07:3272734-3276872 | 1695 | 565 | 62.35 | 9.08 | |

| MdNPF5.8 | MD07G1038800 | Chr07:3237655-3247764 | 1731 | 577 | 63.70 | 8.82 | |

| MdNPF5.9 | MD07G1038600 | Chr07:3176293-3185619 | 1695 | 565 | 62.63 | 9.01 | |

| MdNPF5.10 | MD07G1039600 | Chr07:3353966-3358684 | 1731 | 577 | 63.97 | 8.71 | |

| MdNPF5.11 | MD04G1148300 | Chr04:23666705-23668537 | 1635 | 545 | 60.03 | 6.25 | |

| MdNPF5.12 | MD04G1138500 | Chr04:22623404-22627516 | 1770 | 590 | 65.59 | 8.62 | |

| MdNPF5.13 | MD12G1153900 | Chr12:23405312-23409371 | 1770 | 590 | 65.19 | 8.93 | MG021339 |

| MdNPF5.14 | MD07G1205700 | Chr07:28355985-28360202 | 1794 | 598 | 67.03 | 8.77 | MG021344 |

| MdNPF5.15 | MD01G1141500 | Chr01:25051572-25054193 | 1785 | 595 | 66.39 | 9.24 | |

| MdNPF5.16 | MD17G1041000 | Chr17:2979487-2982673 | 1632 | 544 | 60.48 | 8.35 | MG021336 |

| MdNPF5.17 | MD09G1040700 | Chr09:2607173-2618823 | 1581 | 527 | 58.64 | 8.79 | |

| MdNPF5.18 | MD08G1218300 | Chr08:28077601-28080578 | 1080 | 360 | 40.06 | 5.25 | |

| MdNPF5.19 | MD15G1406700 | Chr15:50693334-50695520 | 1317 | 439 | 48.70 | 6.36 | MG021331 |

| MdNPF5.20 | MD15G1406500 | Chr15:50682947-50684829 | 1377 | 459 | 50.92 | 5.76 | |

| MdNPF5.21 | MD07G1039200 | Chr07:3295281-3306861 | 825 | 275 | 29.88 | 8.94 | |

| MdNPF6.1 | MD08G1022500 | Chr08:1648693-1654146 | 1551 | 517 | 57.45 | 9.00 | |

| MdNPF6.2 | MD15G1019900 | Chr15:1155213-1159411 | 1869 | 623 | 69.53 | 8.46 | |

| MdNPF6.3 | MD16G1142100 | Chr16:10938991-10941873 | 1914 | 638 | 70.17 | 8.56 | MG021341 |

| MdNPF6.4 | MD13G1131800 | Chr13:10003867-10006664 | 1914 | 638 | 70.08 | 7.70 | |

| MdNPF6.5 | MD15G1173800 | Chr15:13572779-13576346 | 1746 | 582 | 63.62 | 9.30 | MG021346 |

| MdNPF6.6 | MD04G1086400 | Chr04:12553185-12555016 | 1011 | 337 | 36.83 | 8.33 | |

| MdNPF6.7 | MD17G1103000 | Chr17:8745481-8748650 | 1773 | 591 | 65.11 | 9.24 | MG021333 |

| MdNPF7.1 | MD11G1017300 | Chr11:1392309-1395225 | 1866 | 622 | 67.81 | 5.82 | |

| MdNPF7.2 | MD03G1016700 | Chr03:1321170-1324060 | 2022 | 674 | 73.81 | 7.30 | |

| MdNPF7.3 | MD03G1016400 | Chr03:1307373-1311107 | 1782 | 594 | 65.21 | 6.59 | |

| MdNPF7.4 | MD07G1082700 | Chr07:8103711-8110134 | 1815 | 605 | 67.04 | 7.80 | |

| MdNPF7.5 | MD02G1228800 | Chr02:27110155-27115346 | 1815 | 605 | 67.22 | 7.64 | |

| MdNPF7.6 | MD06G1029400 | Chr06:3504379-3509435 | 1791 | 597 | 66.37 | 7.89 | |

| MdNPF7.7 | MD16G1277800 | Chr16:37688341-37693389 | 1788 | 596 | 66.44 | 6.71 | |

| MdNPF8.1 | MD12G1160700 | Chr12:24039618-24042029 | 1707 | 569 | 63.32 | 8.60 | MG021334 |

| MdNPF8.2 | MD04G1147500 | Chr04:23563075-23568217 | 2061 | 687 | 76.60 | 8.76 | |

| MdNPF8.3 | MD11G1081100 | Chr11:6913320-6915864 | 1728 | 576 | 63.96 | 8.11 | |

| MdNPF8.4 | MD11G1081200 | Chr11:6931888-6934707 | 1749 | 583 | 64.77 | 8.62 | |

| MdNPF8.5 | MD16G1010600 | Chr16:814341-817396 | 1758 | 586 | 64.39 | 7.18 |

a Gene ID in apple genome (https://www.rosaceae.org/organism/Malus/x-domestica).

2.2. Phylogenetic Tree of NPF in Apple

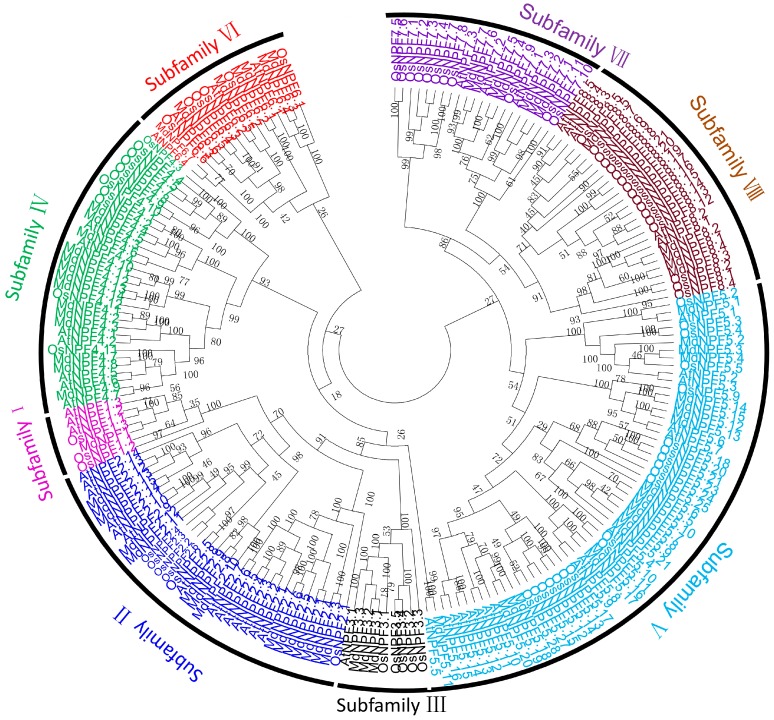

We examined the phylogenetic relationship and function divergence of MdNPF genes by constructing a phylogenetic tree for protein sequences for 73 of them. This tree showed that the MdNPFs could be divided into eight major clades (I–VIII) according to the unified nomenclature. Each clade was considered to be one sub-family. To identify the order of every gene within a subfamily, we gave a second number to each gene. Evolutionary analysis suggested that the eight subfamilies in apple were similar to those found in Arabidopsis and rice (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree and subfamily information for MdNPFs, AtNPFs, and OsNPFs. Neighbor-Joining method was used in tree construction with MEGA 5 software for 205 full-length amino acid sequences from apple, Arabidopsis, and rice. Eight subfamilies are indicated with Roman numerals. The numbers at nodes of the phylogenetic tree indicate the bootstrap values expressing branching probability per 1000 replicates; the bootstrap values of the confidence levels are shown as percentages.

Subfamilies I and II were more closely related to each other, as were subfamilies VI and VIII. Subfamilies I–VIII contained 1, 15, 3, 14, 21, 7, 7, and 5 members, respectively. The 15 NPF members in subfamily II were further divided into two groups (Figure 1).

2.3. Chromosomal Localization Analysis of NPFs in Apple

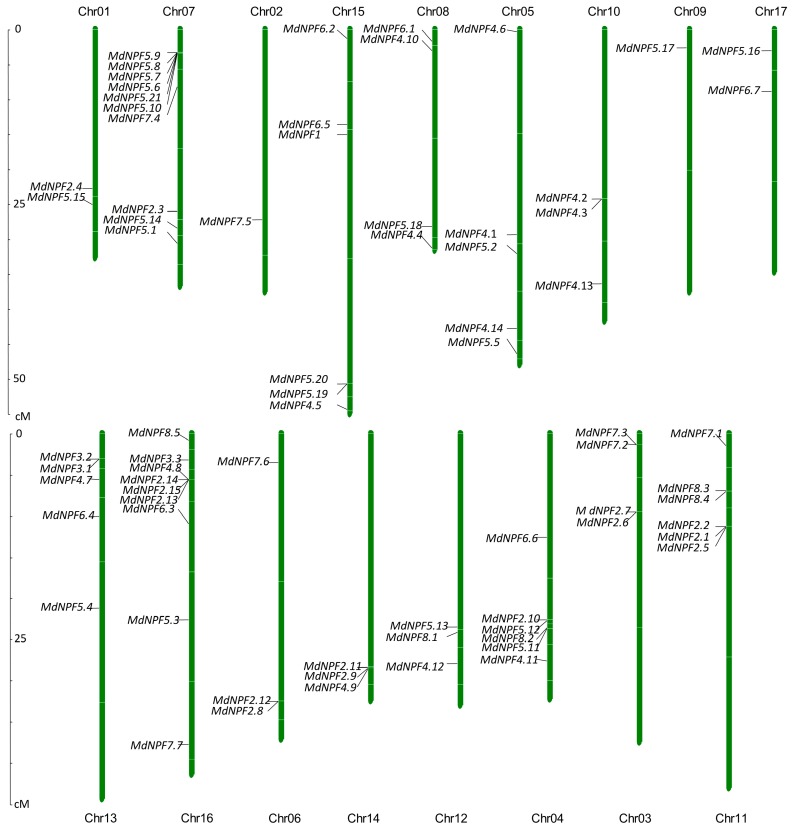

We confirmed the chromosomal location of each NPF according to mapping coordinates for the apple genomic sequence. The 73 MdNPFs were distributed unevenly on 17 apple chromosomes, with Chromosome (Chr) 07 containing 10 genes (MdNPF5.9, MdNPF5.8, MdNPF5.7, MdNPF5.6, MdNPF5.21, MdNPF5.10, MdNPF7.4, MdNPF2.3, MdNPF5.14, and MdNPF5.1), Chr16 having nine (MdNPF8.5, MdNPF3.3, MdNPF4.8, MdNPF2.14, MdNPF2.15, MdNPF2.13, MdNPF6.3, MdNPF5.3, and MdNPF7.7), and Chr02 and Chr09 each having one, i.e., MdNPF7.5 and MdNPF2.17, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Chromosome positions for MdNPF genes, marked with solid black lines. Scale on left is in Mb. Chromosome numbers are indicated on top of bar.

Certain genes were closely aligned on the chromosomes, such as MdNPF5.9, MdNPF5.8, MdNPF5.7, and MdNPF5.6 on Chr07; MdNPF4.2 and MdNPF4.3 on Chr10; and MdNPF8.3 and MdNPF8.4 on Chr11. The distribution pattern of various genes revealed that a particular region of a chromosome or certain chromosomes had a relatively higher density. Their sequence lengths and genetic structure were very similar, which may have indicated serial replication within the apple NPF family.

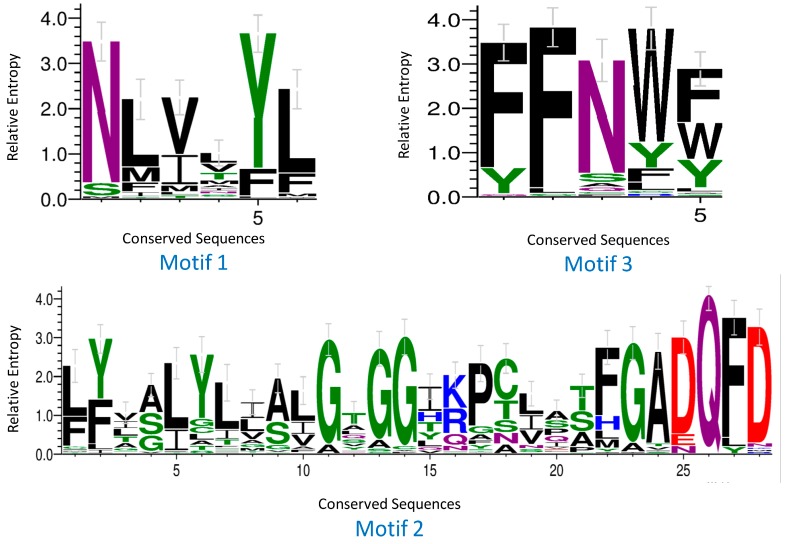

2.4. Analyses of Conserved Domains and TM Regions

Protein sequence analysis demonstrated that each apple NPF contained a complete, conserved NPF domain. The MdNPFs generally possessed 12 TM regions (400–600 aa) that were connected by short peptide loops. A large hydrophilic loop (approximately 100 aa) occurred between the sixth and seventh TM region in each gene (Supplementary Materials, Figure S1. After aligning the protein sequences, we detected three highly conserved motifs in most of the MdNPFs. Motif 1 (NLVxYL) was found between the first and second TM region; Motif 2 (LYxxLYLxALGxGGxK(R)PCxxXFGADQFD) in the fourth TM region; and Motif 3 (FFNWF) at the beginning of the fifth TM region (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sequence analysis of conserved domains from apple NPF proteins. X-axis, sequence of conserved motif; Y-axis, relative entropy that reflects rate of conservation for each amino acid.

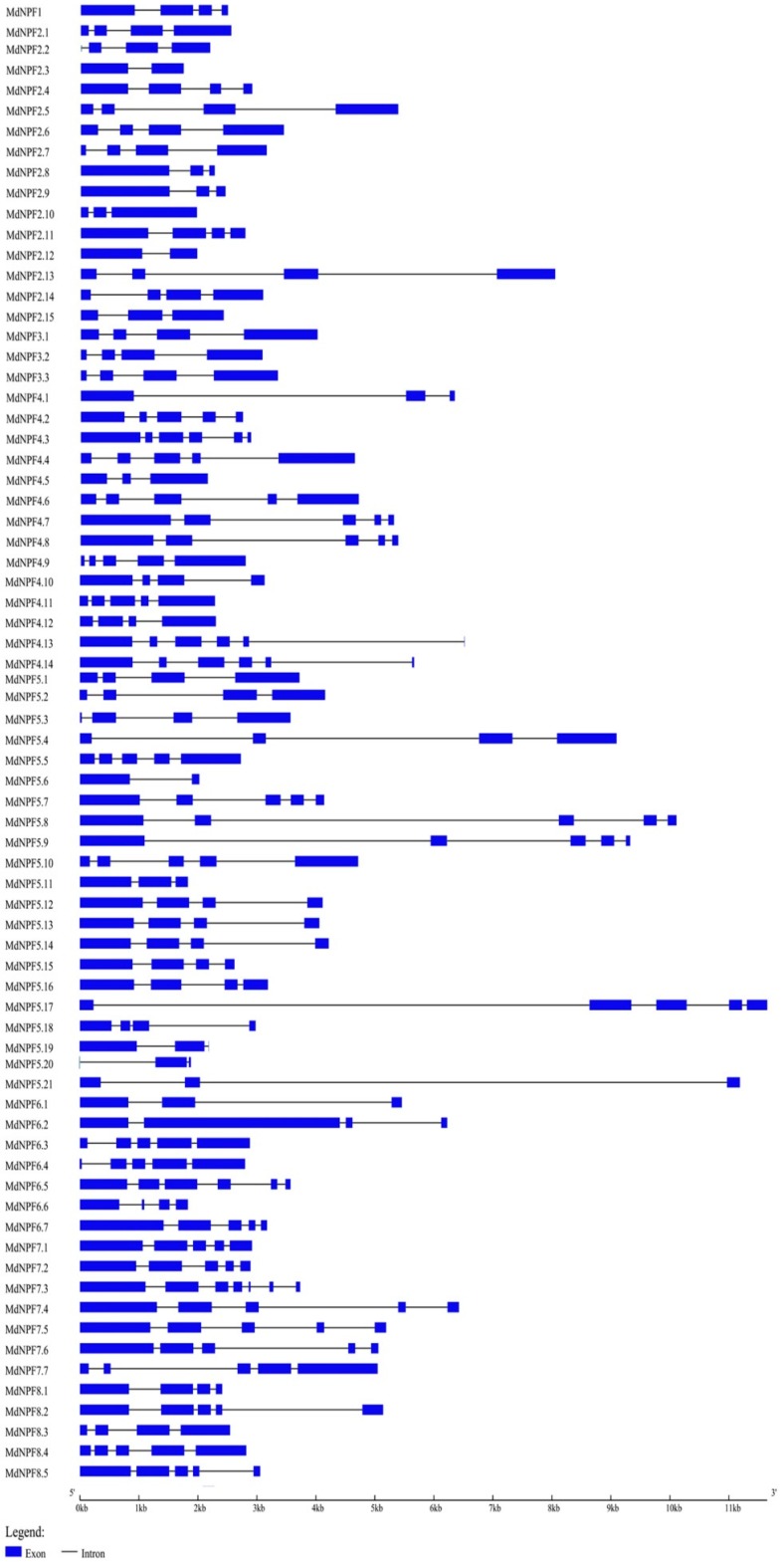

2.5. Comparison of Exon‒Intron Structures for NPF Genes in Apple and Other Species

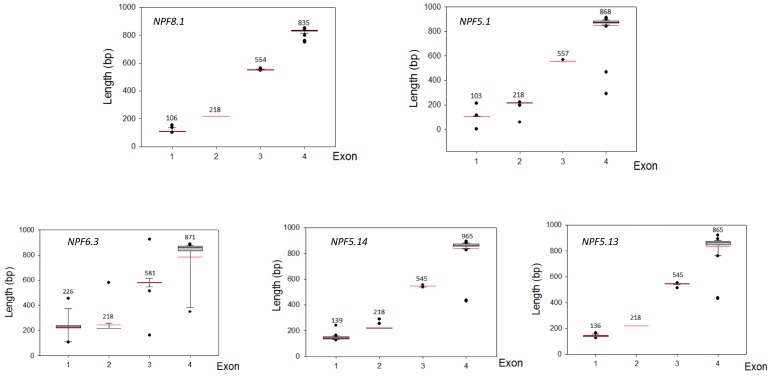

We analyzed the exon‒intron organization of coding sequences for MdNPFs and those genes in some other species. The structures were mapped according to the exon location and gene length of the coding regions (Figure 4). Within the eight clades of MdNPFs, the number of exons was not evenly distributed, but ranged from two to seven. In total, 29 genes (40% of all MdNPFs) had four exons each. In particular, all members of subfamilies I and III contained four exons. Twenty-five genes, mainly in subfamilies IV, V, VII, and VIII, had five exons. The exception was MdNPF7.3, which was the only gene containing seven exons. Genes containing six exons appeared only in subfamilies IV and VI, and included MdNPF4.3, MdNPF4.13, MdNPF4.14, and MdNPF6.5. Three other members in subfamilies II and V—MdNPF2.3, MdNPF2.12, and MdNPF5.6—each had two exons. For the other species, the number of exons was highly consistent, with nearly all containing four exons each, including NPF5.1, NPF5.13, NPF5.14, NPF6.3, and NPF8.1 (Figure 5 and Supplementary Materials, Table S2).

Figure 4.

Structure analysis of apple MdNPF family. Rectangle filled with blue, exon; solid black line, intron. Scale at bottom is in kb.

Figure 5.

Exon-length distribution for NPF5.1, NPF6.3, NPF5.13, NPF5.14, and NPF8.1 in different plant species. Analysis was based on Boxplot depictions in SigmaPlot 12.0 program. Each box represents exon size range in which 50% of values for particular exon are grouped. Mean value is indicated by long red line.

2.6. Analysis of Expression for 14 MdNPFs in Response to Different Nitrate Concentrations

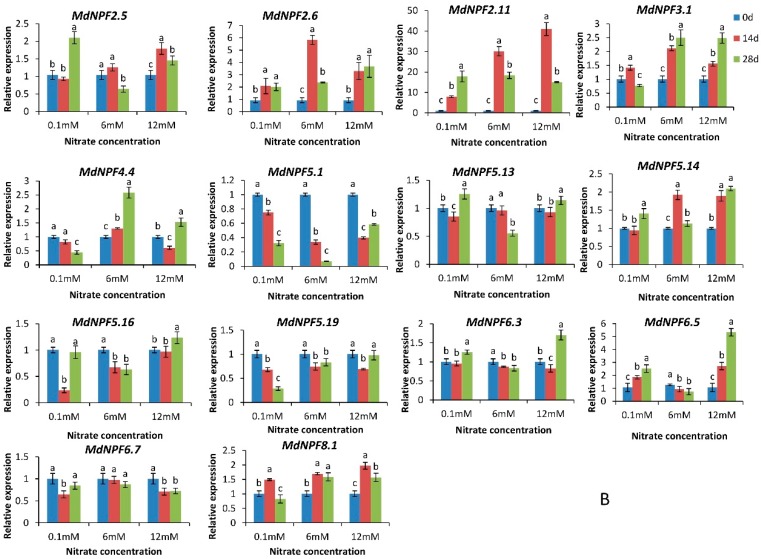

The MdNPFs were constitutively expressed in the roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruit, but transcription levels in specific tissues also varied according to developmental stage (Supplementary Materials, Figure S2). For functional analysis, we cloned 14 MdNPFs (Table 1) and monitored their expression profiles in response to different nitrate concentrations (Figure 6A). Whereas MdNPF2.6, MdNPF3.1, MdNPF5.1, and MdNPF5.9 were induced by low-N treatment, MdNPF2.11 and MdNPF6.7 were up-regulated by high-N conditions when compared with the control plants. In addition, expression of MdNPF3.1 and MdNPF6.5 was up-regulated by both low-and high-nitrate concentrations in 14-day-old roots. When compared with the control, expression of MdNPF3.1 and MdNPF5.1 was up-regulated by almost seven-fold in response to low-N treatment.

Figure 6.

Relative expression levels for 14 cloned apple NPFs under different nitrate concentrations, calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method with respect to control samples (i.e., 6 mM NO3−): (A) the relative expression levels for 14 cloned apple NPFs of roots under different nitrate concentrations; and (B) the relative expression levels for 14 cloned apple NPFs of leaves under different nitrate concentrations. Different letters on the bars within a group indicate significant differences (p < 0.05), based on Tukey’s multiple range tests.

In the leaves, MdNPF2.5 and MdNPF2.6 were up-regulated by more than two-fold under the low-nitrate concentration when compared with the control. Under high-N treatment, MdNPF2.11, MdNPF5.14, MdNPF6.3, and MdNPF8.1 were up-regulated, with transcript levels of MdNPF2.11 increasing by 40-fold. Expression of MdNPF6.5 was up-regulated in both roots and leaves under either nitrate concentration (Figure 6B).

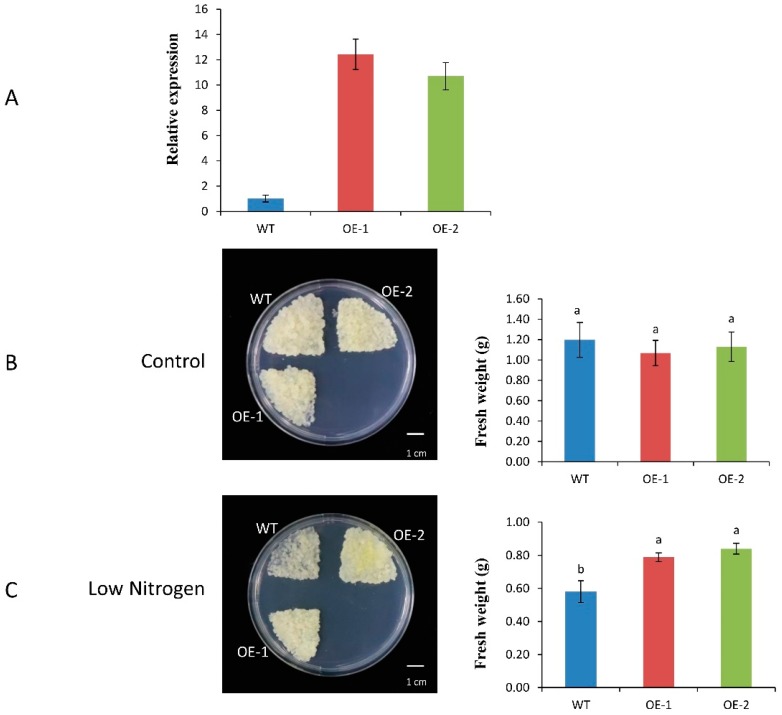

2.7. Effect of Low-Nitrogen Treatment on Growth by Apple Calli Tissue

Two lines of transgenic (35S:MdNPF6.5) apple calli showed relatively higher expression levels (inductions of 11- and 12-fold) when compared with the control (Figure 7A). Whereas growth rates on the MS media were similar among those overexpression calli and the WT (Figure 7B), their phenotypes differed between the control and transgenic lines when transferred to low-N MS media. Biomass production was also significantly greater from the transgenics than from the WT (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Influence of overexpression by MdNPF6.5 on tolerance by apple calli to low-nitrogen supply. (A) Quantitative real time RT-PCR of samples from WT and MdNPF6.5-overexpressors. (B) Assay of low-nitrogen tolerance by WT and MdNPF6.5-overexpressors. Calli were transferred to MS medium or low-nitrogen medium, and photographed at 20 days after treatment began. (C) Comparison of fresh weights from WT and MdNPF6.5-overexpressors in response to low nitrogen. Values are means ± standard deviation. Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences (p < 0.05), based on Tukey’s multiple range tests.

3. Discussion

The NPF genes encode numerous proteins that comprise a large family of members broadly distributed in prokaryotes and eukaryotes [14,38]. As one of the most important fruit crops, apple is widely cultivated in China and around the world due to its high economic and nutritional value. Sequencing of the apple genome has facilitated the identification and analysis of putative apple gene families genome-wide. The encoded proteins include members of the DREB [39], MYB [40], MADS-box [41], PHT [42], RAD23 [43], UGTs [44], SnRK2 [45] and WRKY families [46,47]. Although NPFs have been identified in other species, this family is not as well-understood in apple.

The number of NPF family members varies greatly among species. For example, 51, 53, 68, 80, and 93 genes have been reported for Capsella rubella [19], Arabidopsis [15], poplar [48], Medicago truncatula [49] and rice [19], respectively. By comparison, the apple genome contains 139 NPF genes, making this family much more prominent there than in other species [19]. Using the latest database of apple (version Md3.0), we identified 89 MdNPFs and performed a comprehensive analysis with 73 of them. Examination of the entire genome sequence dataset, sequence alignments, and gene expression provided insight into the apple NPF family.

Our comparison of NPF members among various species revealed that some of those genes have disappeared while others have been duplicated. Such duplication plays a vital role in gene family evolution and diversity, which occurs via three main mechanisms: segmental duplication, tandem duplication, or retro-position. For example, rice contains OsNRT1.1A and OsNRT1.1B, both of which are simultaneously expressed, although the former is mainly expressed in the roots and has a higher transcription level than the latter [50]. Those two genes function similarly to AtNRT1.1 from Arabidopsis [5]. In contrast, three AtNRT1.1-like genes found in grasses may have arisen as a consequence of either a single-based mutation or gene duplication following the dicot‒monocot split [50]. Poplar carries only one AtNRT1.1-like gene and no AtNRT1.4-like gene [5,50]. Although a degraded pseudogene version related to NRT1.6 and NRT1.7 exists in the genome of Sorghum bicolor, no ESTs have been found in any database for that species. The situation is similar for Brachypodium and Zea mays [50]. Therefore, we might hypothesize that these significant contrasts in NRT members between apple and other species is due to gene duplications and deletions in the apple genome, all of which have driven the evolution of MdNPFs to adapt to changes in soil nitrate concentrations.

The MdNPFs are highly and structurally conserved, based on our comprehensive analyses of amino acid sequence alignments, phylogenetics, and conserved domains (Figure 1 and Figure 3 and Supplementary Materials, Figure S1). Similar results have been reported for Arabidopsis [15], rice [14], legume plants such as Medicago [49,51], and poplar [48]. For example, apple NPF2.11, NPF5.1, NPF5.13, NPF6.3, and NPF8.1 share the same exon‒intron structures and exon lengths with members found in other species. Some genes, e.g., NPF5.1 and NPF5.14, have a different number of exons but which are all the same length, probably due to a split or merger during the evolutionary process (Supplementary Materials, Table S2). Consistent with previous findings by Léran et al. [19], our examination revealed that many MdNPF members contain 12 TM regions, with a large hydrophilic loop in the middle and six TMs at either side (Supplementary Materials, Figure S1). We also noted three conserved motifs during our analysis of conserved domains in the apple NPFs. Although rice PTRs also contain three motifs [14], two of their conserved domains differ slightly from those of apple. These findings suggest that the variability in amino acid residues outside the conserved domain might determine the different functions by MdNPF members.

In many species, the expression of some NPF genes can be induced by changes in soil nitrate concentrations [24], external K+ concentrations [52], or other factors [53]. For example, AtNPF6.3 (At NRT1.1) can have one of two Km values, depending upon the nitrate concentration. In Arabidopsis, when the level of nitrate is higher than 1 mM, AtNPF6.3 can behave as a low-affinity transporter but can then switch to a high-affinity mode when that concentration goes below 1 mM, all due to the phosphorylation of intracellular threonine by kinase CIPK23 [54]. Both ZmNPF7.10 and OsNPF7.9 show increased relative expression in the presence of high K+ when compared with performance in response to a low-K+ concentration [52]. Some Arabidopsis NPFs, including NPF1.1, NPF1.2, NPF2.3, NPF2.7, NPF2.9, NPF2.12, NPF2.13, NPF4.6, NPF5.5, NPF6.2, NPF7.2, and NPF7.3, are strictly LATS genes [1]. Our study results indicated that the expression of MdNPFs in roots and leaves fell into one of three categories: Type I, responsive to low-N conditions; Type II, responsive to high-N conditions; or Type III, no concentration-related differences in response. In particular, the Type I genes were MdNPF2.5, MdNPF2.6, MdNPF3.1, MdNPF5.1, MdNPF5.9, and MdNPF6.5, while Type II included MdNPF2.11, MdNPF5.14, MdNPF6.3, MdNPF6.5, and MdNPF8.1. The remaining genes belonged to Type III. Consistent with our results, NPF3.1 and NPF5.14 in Arabidopsis are involved in the transport of NO3− [1]. Expression of MdNPF6.5 (MdNRT1.1) was elevated under both low- and high-N treatment, which suggested that this gene encodes a dual-affinity nitrate transporter such as AtNRT1.1 [54,55]. Therefore, all of these findings demonstrate that NPF genes have important physiological roles and are expressed at different levels depending upon the soil nitrate concentration.

As shown from our experiments, overexpression of MdNPF6.5 can increase apple biomass production under low-N conditions. This is consistent with results from studies of Arabidopsis and rice [5,15]. Taken together, our research confirms that MdNPF6.5 is a promising candidate gene for improving nitrogen uptake and the tolerance of apple plants to low nitrate supplies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of Apple NPF Genes

The Arabidopsis NPF family database was downloaded from the TAIR website (available online: http://www.arabidopsis.org/) [56]. Information about 53 Arabidopsis NPF proteins and the consensus protein sequences of the NPF domain was used for our BlastP search (available online: http://www.rosaceae.org/tools/ncbi_blast) against predicted apple proteins. We then searched all of those NPF sequences against the apple genome database (available online: https://www.rosaceae.org/gb/gbrowse/malus_x_domestica/) with HMMER v3.0 and BlastP [56]. The Pfam database (available online: http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/search) and NCBI-Conserved Domain Search (NCBI-CDD; available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) were used to confirm the reliability of those protein sequences [41].

4.2. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

We used DNAMAN 6.0 (Lynnon Biosoft, San Ramon, CA, USA ) with default parameters to align the multiple sequences of 73 MdNPF protein sequences. A phylogenetic tree of the MdNPF gene family was constructed by MEGA 5.2 software (available online: http://www.megasoftware.net) and the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method, bootstrapping with 1000 replicates. This analysis was based on the amino acid sequences of MdNPF proteins as well as NPF proteins from Arabidopsis and rice [57].

4.3. Analyses of Exon‒Intron Structure and Genome Distribution

Genomic sequences and distributions of chromosomes and NPF genes were downloaded from the apple genome database. Exon‒intron information for orthologs of MdNPF5.1, MdNPF5.13, MdNPF5.14, MdNPF6.3, and MdNPF8.1 in various species were downloaded from PLAZA 3.0 (available online: http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/plaza/) [58]. The exon‒intron structures of MdNPF genes were drawn by gene structure display server 2.0 (available online: http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/). A map of chromosomal positions was completed with MapInspect (available online: www.plantbreeding.wur.nl/UK/software_mapinspect.html) [41].

4.4. Sequence Logo and Prediction of TM Regions

Sequence logos for the conserved domains of MdNPFs were generated by the application WebLogo (available online: http://weblogo.threeplusone.com) [59]. We predicted the TM regions for MdNPFs by using TMHMM Server v.2.0 (available online: http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/).

4.5. Plant Materials and Nitrogen Treatments

To monitor gene expression, we conducted a hydroponics experiment during the growing season in 2017. Seedlings of Malus hupehensis were first cultured in the mixture of sand and soil, with a volume ratio 1:1, until they were 15 cm tall. They were then placed in a hydroponics environment to grow for three weeks in a 1/2 Hoagland nutrient solution consisting of 3.47 mM Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 5.0 mM KNO3, 1.0 mM K2HPO4, 2.0 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 2.5 mM FeSO4·7H2O, 2.5 mM EDTA-Na, 0.046 mM H3BO3, 0.0067 mM MnCl2·4H2O, 0.00077 mM ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.00032 mM CuSO4·5H2O, and 0.00011 mM H2MoO4·H2O (pH 6.0). Afterwards, the seedlings were cultivated in a modified Hoagland nutrient solution containing either 0.01 (low-N) or 12 mM nitrate (high-N). As the control treatment, we used a 6 mM nitrate solution. Young roots and leaves were collected on Days 0, 14, and 28 of treatment to examine the effects of different nitrate concentrations on MdNPF expression. All samples were frozen immediately in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C prior to RNA extraction.

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of apple “Orin” calli tissue was performed by using the open reading frame (ORF) cDNA of MdNPF6.5 and cloning into vector pBI121 to produce the overexpression construct. The callus tissue was genetically transformed as described by Hu et al. [60]. Following identification, the transgenic calli were cultured on 11/12 MS medium without nitrogen and 1/12 MS medium for low N treatment. Other growth conditions remained the same. Photographs were taken and fresh weights recorded after 20 days of N-deficient treatment.

4.6. Quantitative Real Time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and Gene-Cloning

Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissues with a Wolact® Plant RNA Isolation kit (Vicband, Hong Kong, China). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized by adding 2 μg to the reaction mixture. For the qRT-PCR assays, reverse-transcription was performed with 1 μg of total RNA from each sample, followed by PCR-amplification of 1 μL of the product. Previously prepared cDNA was used for qRT-PCR assays conducted in a 20-µL reaction system that included 10 µL of SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (TaKaRa, Kyoto, Japan) and used a QuantStudio®5 instrument (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as described before [61].

The Primers used for quantitative real time RT-PCR amplifications are listed in Supplementary Materials, Table S3. The RT-PCR amplifications involved an initial 95 °C for 3 min; 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 15 s; 3 min at 72 °C; and 81 cycles of 7 s each that increased by an increment of 0.5 °C, from 55 °C to 95 °C. Three biological replicates were set up for each assay and the ΔCt values were calculated by using MdMDH as the endogenous control [62]. The values of relative quantification were calculated based on the 2−ΔΔCt method [63] and dissociation curve analysis was used to determine the specificity of the amplifications.

The PCR reaction conditions for gene-cloning were 32 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 10 s, and 72 °C for 2 min, followed by 2 min extension at 72 °C. Primers used for gene-cloning are shown in Supplementary Materials, Table S4.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed with SPSS 16.0 software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s tests were used to compare the results under different nitrate concentrations versus the control.

5. Conclusions

We identified 73 MdNPFs in the apple genome and determined their expression patterns that varied according to tissue type and concentration of nitrate in nutrient solution. These results provide new information that can be applied to further investigations into the functions of apple NPFs when plants are responding to changes in nitrate levels. In particular, MdNPF6.5 shows potential for research efforts to improve tolerance to nitrogen deficiencies by apple and, possibly, other crops.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Zhengwei Ma for management of the apple trees.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials can be found at http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/9/2761/s1.

Author Contributions

C.L. (Changhai Liu) and Q.D. designed the experiments; Q.W. and D.H. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; C.L. (Cuiying Li) provided materials; F.M. and P.L. contributed reagents and instrument; and Q.W. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final submission.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0201100/30) and by the earmarked fund for the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-27).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.O’Brien J.A., Vega A., Bouguyon E., Krouk G., Gojon A., Coruzzi G., Gutiérrez R.A. Nitrate transport, sensing, and responses in plants. Mol. Plant. 2016;9:837–856. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krapp A. Plant nitrogen assimilation and its regulation: A complex puzzle with missing pieces. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015;25:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willmann A., Thomfohrde S., Haensch R., Nehls U. The poplar NRT2 gene family of high affinity nitrate importers: Impact of nitrogen nutrition and ectomycorrhiza formation. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014;108:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu B., Wang W., Ou S.J., Tang J.Y., Li H., Che R.H., Zhang Z.H., Chai X.Y., Wang H.R., Wang Y.Q., et al. Variation in NRT1.1B contributes to nitrate-use divergence between rice subspecies. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:834–838. doi: 10.1038/ng.3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W., Hu B., Yuan D.Y. Expression of the nitrate transporter gene OsNRT1.1A/OsNPF6.3 confers high yield and early maturation in rice. Plant Cell. 2018;30:638–651. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claussen W. Growth, water use efficiency, and proline content of hydroponically grown tomato plants as affected by nitrogen source and nutrient concentration. Plant Soil. 2002;247:199–209. doi: 10.1023/A:1021453432329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang L.L., Li M.J., Zhou K., Sun T.T., Hu L.Y., Li C.Y., Ma F.W. Uptake and metabolism of ammonium and nitrate in response to drought stress in Malus prunifolia. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018;127:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldmann K.A. The herbicide sensitivity gene CHL1 of Arabidopsis encodes a nitrate-inducible nitrate transporter. Cell. 1993;72:705–713. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90399-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mounier E., Pervent M., Ljung K., Gojon A., Nacry P. Auxin-mediated nitrate signalling by NRT1.1 participates in the adaptive response of Arabidopsis root architecture to the spatial heterogeneity of nitrate availability. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37:162–174. doi: 10.1111/pce.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin S.H., Kuo H.F., Canivenc G., Lin C.S., Lepetit M., Hsu P.K., Tillard P., Lin H.L., Wang Y.Y., Tsai C.B., et al. Mutation of the Arabidopsis NRT1.5 nitrate transporter causes defective root to-shoot nitrate transport. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2514–2528. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almagro A., Lin S.H., Tsay Y.F. Characterization of the Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.6 reveals a role of nitrate in early embryo development. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3289–3299. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulsen I.T., Skurray R.A. The POT family of transport proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1994;19:404. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner H.Y., Naider F., Becker J.M. The PTR family: A new group of peptide transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;16:825–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao X.B., Huang J.Y., Yu H.H. Genomic survey, characterization and expression profile analysis of the peptide transporter family in rice (Oryzasativa L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsay Y.F., Chiu C.C., Tsai C.B., Ho C.H., Hsu P.K. Nitrate transporters and peptide transporters. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2290–2300. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karim S., Lundh D., Holmström K.O., Mandal A., Pirhonen M. Structural and functional characterization of AtPTR3, a stress-induced peptide transporter of Arabidopsis. J. Mol. Model. 2005;11:226–236. doi: 10.1007/s00894-005-0257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karim S., Holmström K.O., Mandal A., Dahl P., Hohmann S., Brader G., Palva E.T., Pirhonen M. AtPTR3 a wound-induced peptide transporter needed for defence against virulent bacterial pathogens in Arabidopsis. Planta. 2007;225:1431–1445. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komarova N.Y., Thor K., Gubler A., Meier S., Dietrich D., Weichert A., Grotemeyer M.S., Tegeder M., Rentsch D. AtPTR1 and AtPTR5 transport dipeptides in planta. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:856–869. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.123844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Léran S., Varala K., Boyer J.C., Chiurazzi M., Crawford N., Daniel-Vedele F., David L., Dickstein R., Fernandez E., Forde B., et al. A unified nomenclature of NITRATE TRANSPORTER 1/PEPTIDE TRANSPORTER family members in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jørgensen M.E., Xu D.Y., Crocoll C., Ramírez D., Motawia M.S., Olsen C.E., Nour-Eldin H.H., Kiba T., Feria-Bourrellier A.B., Lafouge F., et al. The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT2.4 plays a double role in roots and shoots of nitrogen-starved plants. Plant Cell. 2012;24:245–258. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.092221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nour-Eldin H.H., Andersen T.G., Burow M., Madsen S.R., Jørgensen M.E., Olsen C.E., Dreyer I., Hedrich R., Geiger D., Halkier B.A. NRT/PTR transporters are essential for translocation of glucosinolate defence compounds to seeds. Nature. 2012;488:531–534. doi: 10.1038/nature11285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boursiac Y., Léran S., Corratgé-Faillie C., Gojon A., Krouk G., Lacombe B. ABA transport and transporters. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tal I., Zhang Y., Jorgensen M.E., Pisanty O., Barbosa I.C.R., Zourelidou M., Regnault T., Crocoll C., Olsen C.E., Weinstain R., et al. The Arabidopsis NPF3 protein is a GA transporter. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11486–11496. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu P.K., Tsay Y.F. Two phloem nitrate transporters, NRT1.11 and NRT1.12, are important for redistributing xylem-borne nitrate to enhance plant growth. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:844–856. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.226563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang G.B., Gong J.M. The Arabidopsis ethylene/jasmonic acid-NRT signaling module coordinates nitrate reallocation and the trade-off between growth and environmental adaptation. Plant Cell. 2014;26:3984–3998. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.129296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Léran S., Garg B., Boursiac Y., Corratgé-Faillie C., Brachet C., Tillard P., Gojon A., Lacombe B. AtNPF5.5, a nitrate transporter affecting nitrogen accumulation in Arabidopsis embryo. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:7962. doi: 10.1038/srep07962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pike S., Gao F., Kim M.J., Kim S.H., Schachtman D.P., Gassmann W. Members of the NPF3 transporter subfamily encode pathogen-inducible nitrate/nitrite transporters in grapevine and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:162–170. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen S., Li F.X., Liu D., Jiang C.H., Cui L.J., Shen L.L., Liu G.S., Yang A.G. Dynamic expression analysis of early response genes induced by potato virus Y in PVY-resistant Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:297–311. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chopin F., Orsel M., Dorbe M.F., Chardon F., Truong H.N., Miller A.J., Krapp A., Daniel-Vedele F. The Arabidopsis AtNRT2.7 nitrate transporter controls nitrate content in seeds. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1590–1602. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan S.C., Lin C.S., Hsu P.K., Lin S.H., Tsay Y.F. The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT1.7, expressed in phloem, is responsible for source-to-sink remobilization of nitrate. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2750–2761. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia X.D., Fan X.R., Wei J. Rice nitrate transporter OsNPF2.4 functions in low-affinity acquisition and long-distance transport. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:317–331. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan X.R., Tang Z., Tan Y., Zhang Y., Luo B., Yang M., Lian X.M., Shen Q.R., Miller A.J., Xu G.H. Overexpression of a pH-sensitive nitrate transporter in rice increases crop yields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:7118–7123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525184113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang S.Y., Sun J.Y., Tian Z.W., Hu H., Michel E.J.S., Gao J.W., Jiang D., Cao W.X., Dai T.B. Root extension and nitrate transporter up-regulation induced by nitrogen deficiency improves nitrogen status and plant growth at the seedling stage of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017;141:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo J., Li H., Liu T.X., Polle A., Peng C.H., Luo Z.B. Nitrogen metabolism of two contrasting poplar species during acclimation to limiting nitrogen availability. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:4207–4224. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valkov V.T., Rogato A., Alves L.M., Sol S., Noguero M., Léran S., Lacombe B., Chiurazzi M. The nitrate transporter family protein LjNPF8.6 controls the N-fixing nodule activity. Plant Physiol. 2017;175:1269–1282. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu Y.L., Yi H.Y., Bao J., Gong J.M. LeNRT2.3 functions in nitrate acquisition and long-distance transport in tomato. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1072–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi H.L., Ma W.J., Song J.Y., Lu M., Rahman S.U., Bui T.T.X., Vu D.D., Zheng H.F., Wang J.H., Zhang Y. Physiological and transcriptional responses of Catalpa bungei to drought stress under sufficient- and deficient-nitrogen conditions. Tree Physiol. 2017;247:1–12. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpx090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saier M.H., Jr. Families of transmembrane transporters selective for amino acids and their derivatives. Microbiology. 2000;146:1775–1795. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao T., Liang D., Wang P., Liu J.Y., Ma F.W. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of the DREB transcription factor gene family in Malus under abiotic stress. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2012;287:423–436. doi: 10.1007/s00438-012-0687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao Z.H., Zhang S.Z., Wang R.K., Zhang R.F., Hao Y.J. Genome wide analysis of the apple MYB transcription factor family allows the identification of MdoMYB121 gene conferring abiotic stress tolerance in plants. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e69955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian Y., Dong Q.L., Ji Z.R., Chi F.M., Cong P.H., Zhou Z.S. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MADS-box gene family in apple. Gene. 2015;555:277–290. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun T.T., Li M.J., Shao Y., Yu L.Y., Ma F.W. Comprehensive genomic identification and expression analysis of the phosphate transporter (PHT) gene family in apple. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:426. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang N., Gong X.Q., Ma F.W. Genome-wide identification of the radiation sensitivity protein-23 (RAD23) family members in apple (Malus×domestica Borkh.) and expression analysis of their stress responsiveness. J. Integr. Agric. 2017;16:820–827. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(16)61517-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou K., Hu L.Y., Li P.M., Gong X.Q., Ma F.W. Genome-wide identification of glycosyltransferases converting phloretin to phloridzin in Malus species. Plant Sci. 2017;265:131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shao Y., Qin Y., Zou Y.J., Ma F.W. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of the SnRK2 gene family in Malus prunifolia. Gene. 2014;552:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gu Y.B., Ji Z.R., Chi F.M., Qiao Z., Xu C.N., Zhang J.X., Dong Q.L., Zhou Z.S. Bioinformatics and expression analysis of the WRKY gene family in apple. Scient. Agric. Sin. 2015;48:3221–3238. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meng D., Li Y.Y., Bai Y., Li M.J., Cheng L.L. Genome-wide identification and characterization of WRKY transcriptional factor family in apple and analysis of their responses to waterlogging and drought stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016;103:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bai H., Euring D., Volmer K., Janz D., Polle A. The nitrate transporter (NRT) gene family in poplar. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pellizzaro A., Alibert B., Planchet E., Limami A.M., Morère-Le Paven M.C. Nitrate transporters: An overview in legumes. Planta. 2017;246:585–595. doi: 10.1007/s00425-017-2724-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plett D., Toubia J., Garnett T., Tester M., Kaiser B.N., Baumann U. Dichotomy in the NRT gene families of dicots and grass species. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e72126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang H.B., Krishnakumar V., Bidwell S., Rosen B., Chan A., Zhou S.G., Gentzbittel L., Childs K.L., Yandell M., Gundlach H., et al. An improved genome release (version Mt4.0) for the model legume Medicago truncatula. BMC Genom. 2014;15:312. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H., Yu M., Du X.Q., Wang Z.F., Wu W.H., Quintero F.J., Jin X.H., Li H.D., Wang Y. NRT1.5/NPF7.3 functions as a proton-coupled H+/K+ antiporter for K+ loading into the xylem in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2017;29:2016–2026. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drechsler N., Courty P.E., Brulé D., Kunze R. Identification of arbuscular mycorrhiza-inducible Nitrate Transporter 1/Peptide Transporter Family (NPF) genes in rice. Mycorrhiza. 2018;28:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s00572-017-0802-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu K.H., Tsay Y.F. Switching between the two action modes of the dual-affinity nitrate transporter CHL1 by phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2003;22:1005–1013. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu K.H., Huang C.Y., Tsay Y.F. CHL1 is a dual-affinity nitrate transporter of Arabidopsis involved in multiple phases of nitrate uptake. Plant Cell. 1999;11:865–874. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.5.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He Z., Li L., Luan S. Immunophilins and parvulins. Superfamily of peptidyl prolyl isomerases in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1248–1267. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.031005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szklarczyk D., Franceschini A., Wyder S., Forslund K., Heller D., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Roth A., Santos A., Tsafou K.P., et al. STRING v10: Protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:447–452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bailly A., Sovero V., Vincenzetti V., Santelia D., Bartnik D., Koening B.W., Mancuso S., Martinoia E., Geisler M. Modulation of P-glycoproteins by auxin transport inhibitors is mediated by interaction with immunophilins. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:21817–21826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crooks G.E., Hon G., Chandonia J.M., Brenner S.E. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu D.G., Li M., Luo H., Dong Q.L., Yao Y.X., You C.X., Hao Y.J. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of MdSOS2 reveals its involvement in salt tolerance in apple callus and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31:713–722. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dong Q.L., Zhao S., Duan D.Y., Tian Y., Wang Y.P., Mao K., Zhou Z.S., Ma F.W. Structural and functional analyses of genes encoding VQ proteins in apple. Plant Sci. 2018;272:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perini P., Pasquali G., Margis-Pinheiro M., Oliviera P.R.D., Revers L.F. Reference genes for transcriptional analysis of flowering and fruit ripening stages in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) Mol. Breed. 2014;34:829–842. doi: 10.1007/s11032-014-0078-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.