Abstract

The practice of kidney paired donation (KPD) is expanding annually, offering the opportunity for live donor kidney transplantation to more patients. We sought to identify if voluntary KPD networks such as the National Kidney Registry (NKR) were selecting or attracting a narrower group of donors or recipients compared to national registries. For this purpose, we merged data from the NKR database with the SRTR database from February 14, 2008 to February 14, 2017, encompassing the first 9 years of the NKR. When compared to all UNOS live donor transplants (49,610), all UNOS living unrelated transplants (23,319), and all other KPD transplants (4,236), the demographic and clinical characteristics of NKR transplants (2,037) appear similar to contemporary national trends. In particular, among the NKR patients there were a significantly (p <0.001) greater number of retransplants (25.6 vs. 11.5%), hyperimmunized recipients (22.7 vs. 4.3% were cPRA >80%), females (45.9 vs. 37.6%), black recipients (18.2 vs. 13%), and those on public insurance (49.7 vs. 41.8%) compared to controls. These results support the need for greater sharing and larger pool sizes, perhaps enhanced by entry of compatible pairs and even chains initiated by deceased donors, to unlock more opportunities for those harder to match pairs.

Introduction

The concepts and practical considerations for Kidney Paired Donation (KPD) were suggested over 3 decades ago when living kidney transplantation was almost exclusively performed between biological relatives [1]. During the last three decades, the practice of live donor kidney transplantation between spouses and unrelated individuals has matured and become standard practice in virtually all transplant centers [2]. A number of additional advances have now made the clinical practice of exchanging kidneys between patients in different transplant centers commonplace. The major pieces that needed to be tested and validated were the successful outcomes obtained when unrelated donors and recipients exchange kidneys, and the ability to safely preserve and ship living donor kidneys over distances sufficient to permit exchanges between multiple geographic regions [3–7]. The National Kidney Registry (NKR) is a voluntary network of 83 transplant centers in 32 States in the United States (US), focused on the timely transplantation of live donor kidneys through novel computational algorithms that facilitate exchanges of kidneys between member centers. At the current time this consortium has performed the largest number of KPD transplants in the US [8].

An important question to ask as kidney paired exchange continues to grow is precisely who is entered into these networks, and who are the donors and recipients actually being transplanted? The primary indications for KPD are ABO incompatibility (ABOi) and/or lymphocytotoxic crossmatch reactivity [3–7]. In addition, a smaller but growing number of patients are compatible pairs who are seeking anatomic, physiologic, or immunologic advantage from a paired exchange [9]. A second question to explore at this time is the possibility that KPD transplants are favoring one demographic group over another? On a national level the transplantation of a kidney between a donor and a recipient is governed by a set of rules that is intended to emphasize medical criteria, safety, equity, and ethical constructs [10–12]. This report will attempt to focus on these questions and identify if unintended consequences in patient selection during kidney paired exchange have emerged.

Methods and Materials

The National Kidney Registry

This study used data from the NKR, which is a non-profit, 501c organization comprised of 76 transplant centers within the U.S. participating during this study period. The NKR policies are available online [8]. Protocols for evaluating patients, performing the transplant procedures, and post-operative care are outlined by the NKR, however ultimately carried out by the participating transplant centers abiding by, and in concordance with, the individual center protocols. To date, the NKR has facilitated over 2000 KPD exchanges, greater than 80% of which involve shipping the living donor organ across the U.S. The NKR repository is updated at quarterly intervals from each of the participating transplant centers performing KPD transplants within the network. For the purpose of this report the study population comprised all NKR donors and recipients transplanted between February 14, 2008 and February 14, 2017. This represented 2,037 consecutive KPD transplants, 9 years inclusive.

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

This study also used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) external release made available in September 2017. The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, waitlist candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), and has been previously described [13]. The Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. Using SRTR, we identified 101,718 adult (age≥18) recipients (all donor sources) who underwent kidney transplantation between February 14, 2008 and February 14, 2017.

Data Linkage

Data from KPD transplants facilitated through the NKR reported in the registry were linked to the SRTR data and cross validated using encrypted unique identifiers, transplant center, transplant date, donor ABO, donor gender, recipient ABO, and recipient gender.

Statistical Analysis

These study patients were compared to three distinct control populations from which the NKR transplants were subtracted.

Control Population 1: All live donor kidney-only transplants reported to the SRTR registry between February 14, 2008 and February 14, 2017. This comprised 49,610 transplants.

Control Population 2. All living unrelated kidney-only transplants reported to the SRTR registry between February 14, 2008 and February 14, 2017. Any recipient-donor pairs who were biologically related were excluded. This comprised 23,319 transplants.

Control Population 3. All living unrelated kidney-only transplants from the SRTR registry between February 14, 2008 and February 14, 2017 that were designated as part of the UNOS or any other KPD network, excluding the NKR. Any KPD recipient-donor pair who were biologically related were excluded. This comprised 4,236 transplants.

The demographic, immunologic, and clinical data for the transplanted donors and recipients were collected and tabulated. These included recipient date of transplant and center, age, gender, race (White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, other), years on dialysis, BMI (kg/m2), hepatitis C serology, diabetes, hypertension, prior transplants, pre-emptive transplants, education level, employment status, public/private insurance, and HLA sensitization at transplant according to calculated panel reactive antibody (cPRA 0%, 1–79%, 80–97%, and 98–100%). Donor characteristics included age, gender, race (White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, other), BMI (kg/m2), and eGFR (abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) at donation. Additional transplant characteristics included ABO compatible and ABO incompatible pairs, the number of HLA zero mismatches (HLA A, B, Dr), and the recorded total cold ischemia times (CIT) at revascularization. The study was reviewed and approved by the Cleveland Clinic IRB #16–784.

Differences in recipient, donor, and transplant characteristics between NKR and control transplants were assessed using the χ2 (categorical variables) and Mann-Whitney rank-sum (continuous variables) tests. We used a two-sided α of 0.05 to indicate a statistically significant difference. All analyses were performed using Stata 15/MP for Linux (College Station, Texas).

Results

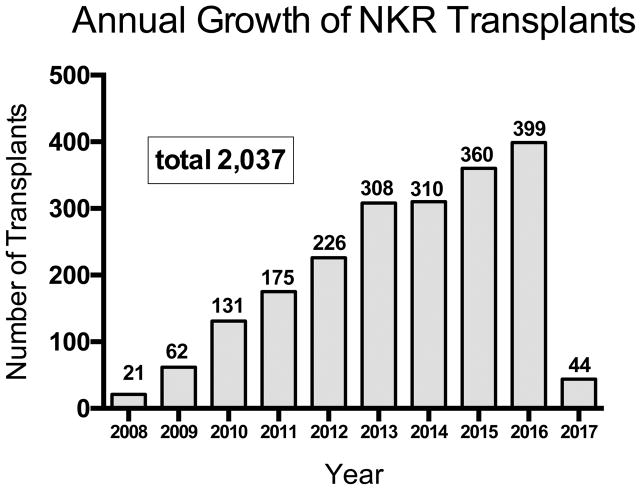

The annual growth in NKR transplants has continued through the initial 9 years of the program with 2,037 transplants performed to the study end date of February 14, 2017 (Figure 1). These exchanges have been facilitated through 416 non-directed donor-initiated chains ranging from 2–35 pairs in length, mean [SD] = 4.42 [3.78] and 86 loops, (mean [SD] = 2.34 [0.67] per chain. Kidneys were shipped between 22 states including 14.7% within centers, 4.4% within the same city under 25 miles, and 80.9% greater than 25 miles. Transport included surface transportation and both commercial and charter flights. The median CIT (hours) for the NKR transplants was 8.7 (IQR: 5.2–12.0); range 2–25; and the number of HLA A, B, DR mismatches were mean 3.85; median 4; range 0–6. The time waiting from entry into KPD to actual transplant ranged from 0–42 months and varied according to recipient ABO blood type and cPRA. Recipients with blood types AB, A, and B had shorter mean wait times in months, (1.89, 2.69, 3.73, respectively), compared with type O (6.48); all p <0.0001) (Table 1). The mean wait times in months were cPRA 0% (3.48), 1–19% (3.67), 20–79% (3.78), 80–97% (5.41), and 98–100% (9.44), p<0.0001.

Figure 1.

Annual Growth of NKR Transplants. February 14, 2008 to February 14, 2017.

Table 1.

Wait times, ABO blood types and HLA sensitization for NKR transplant recipients

| Recipients | Wait Time Registration to Transplant | cPRA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABO N | Mean months | Range months | O% | 1–19% | 20–79% | 80–97% | 98–100% |

| A: 731 | 2.69 | 0–29 | 295 | 49 | 194 | 130 | 63 |

| B: 372 | 3.73 | 0–27 | 185 | 24 | 90 | 51 | 22 |

| O: 786 | 6.48* | 0–37 | 351 | 60 | 209 | 116 | 50(2.5%) |

| AB: 148 | 1.89 | 0–42 | 79 | 10 | 33 | 20 | 6 |

| Total | 910 | 143 | 526 | 317 | 141 | ||

| 2,037 (100%) | 44.6% | 7% | 25.8% | 15.6% | 7% | ||

O vs. all groups p<0.0001

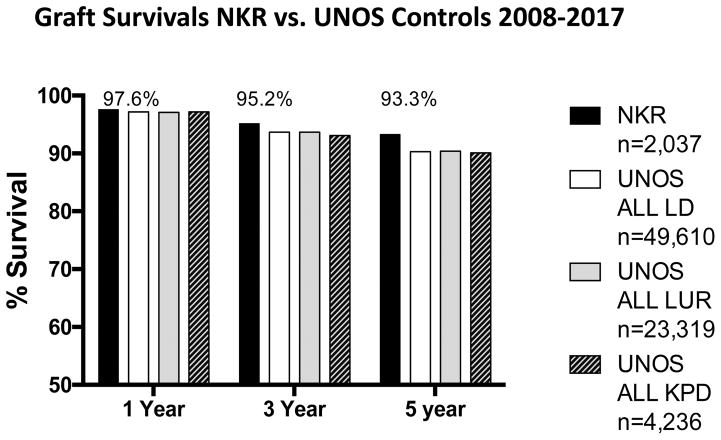

Actuarial 1-3-5-year graft survivals for the NKR transplants and the three controls groups are provided in Figure 2. The differences were not significant at 1 and three years among the groups. However, the differences did reach significance (P <0.01) at 5 years. For the NKR transplants the frequency of primary non-function (recipient never off dialysis) was 0.34% (n=7) and the frequency of delayed graft function (first week dialysis) was 4.9% (n=101).

Figure 2.

Actuarial all cause kidney transplant 1-3-5 year graft survivals for NKR vs. UNOS all live donors, UNOS living unrelated donors, and UNOS KPD donors.

Recipient Characteristics

Recipient and donor demographics are provided in Table 2 compared to the three control populations (All UNOS LD; All UNOS LUR; Other KPD transplants). The NKR recipient median age of 50 years (IQR 39–60) is comparable to the controls, while the proportion of females 45.9%, is significantly higher (p<0.001) than the three control populations. The NKR transplants had fewer of white recipients 60.8%, than the controls (p <0.001). In particular, the proportion of Black KPD recipients 18.2% was significantly larger (P <0.001) than the controls, 13%, 11.7%, 13.4%, respectively. The proportion of NKR Hispanic recipients 11.5% was somewhat less than the total UNOS LD transplants 14.7%, but similar to the other controls. The NKR recipients represented a significantly (p < 0.001) increased proportion of retransplants 25.6%, compared to the controls 11.5%, 12.3%. 17.1%, respectively, but a similar proportion of pre-emptive transplants 35.8%. Compared to controls the NKR recipients had a greater number of years on dialysis (median 1.3 vs. 0.5, 0.6, 0.9, respectively, p < 0.001) prior to transplant. The BMI was within 1kg/m2 for the entire population. A lower proportion 44.3%, (p < 0.001) of the NKR recipients were employed at the time of transplant than the controls 48.6%, 52.3%, and 46.4%, respectively. In addition, a greater proportion 49.7%, (p < 0.001) of the NKR recipients were on public health insurance plans at the time of transplant compared to the controls 41.8%, 39.2%, and 45.3%, respectively.

Table 2.

Recipient and Donor Characteristics

| Recipient Characteristics | National Kidney Registry | All UNOS non-NKR Living Donor Transplants |

p value | All UNOS non-NKR Living Unrelated Donor Transplants |

p value | All UNOS non-NKR KPD Living Donor Transplants |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2,037 | 49,610 | 23,319 | 4,236 | |||

| Median (IQR) Age | 50.0 (39.0–60.0) | 49.0 (36.0–59.0) | <0.001 | 50.0 (40.0–59.0) | 0.5 | 50.0 (39.0–59.0) | 0.2 |

| % Female | 45.9 | 37.6 | <0.001 | 34.7 | <0.001 | 42.7 | <0.02 |

| % White | 60.8 | 66.3 | <0.001 | 70.8 | <0.001 | 67.6 | <0.001 |

| % African-American | 18.2 | 13 | <0.001 | 11.7 | <0.001 | 13.4 | <0.001 |

| % Hispanic | 11.5 | 14.7 | <0.001 | 11.5 | 1.0 | 12.4 | 0.3 |

| % Asian | 8.4 | 4.7 | <0.001 | 4.7 | <0.001 | 4.7 | <0.001 |

| % Other | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 0.1 |

| % Previous Transplant | 25.6 | 11.5 | <0.001 | 12.3 | <0.001 | 17.1 | <0.001 |

| % Pre-emptive Transplant | 35.8 | 35.1 | <0.001 | 35.3 | <0.001 | 27.8 | <0.01 |

| Median (IQR) Years on Dialysis | 1.3 (0.0–2.9) | 0.5 (0.0–1.6) | <0.001 | 0.6 (0.0–1.7) | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.0–2.3) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) BMI | 26.6 (23.3–31.0) | 27.1 (23.5–31.4) | 0.01 | 27.5 (23.9–31.7) | <0.001 | 27.4 (23.7–31.7) | <0.001 |

| % College Educated | 64.3 | 59.6 | <0.001 | 65.2 | 0.4 | 63.1 | 0.4 |

| % Employed | 44.3 | 48.6 | <0.001 | 52.3 | <0.001 | 46.4 | 0.1 |

| % Public Insurance | 49.7 | 41.8 | <0.001 | 39.2 | <0.001 | 45.3 | <0.01 |

| % Diabetes | 19 | 20.4 | 0.1 | 21.1 | 0.03 | 20.3 | 0.2 |

| % Hypertension | 15.8 | 16.1 | 0.7 | 15.3 | 0.6 | 15.9 | 0.9 |

| % HCV | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 0.8 |

| Donor Characteristics | |||||||

| Median (IQR) Age | 45.0 (35.0–53.0) | 42.0 (33.0–51.0) | <0.001 | 45.0 (35.0–53.0) | 0.5 | 44.0 (34.0–52.0) | <0.01 |

| % Female | 62.3 | 62.1 | 0.9 | 65.4 | <0.01 | 61.8 | 0.7 |

| % African-American | 10.5 | 11.1 | 0.4 | 7.7 | <0.001 | 7.5 | <0.001 |

| % Hispanic | 10.1 | 14.4 | <0.001 | 10.5 | 0.6 | 10.1 | 1.0 |

| % ABO Incompatible | 2.2 | 1.6 | 0.04 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 0.9 |

| % Zero HLA mismatch | 0.8 | 7.3 | <0.001 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Median (IQR) Cold Ischemia hr | 8.7 (5.2–12.0) | 1.0 (0.7–2.0) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.7–2.0) | <0.001 | 1.4 (0.8–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) BMI | 26.2 (23.3–28.9) | 26.7 (23.8–29.7) | <0.001 | 26.6 (23.8–29.6) | <0.001 | 26.3 (23.6–29.3) | 0.03 |

| Median (IQR) eGFR cc/min | 102.2 (85.8–115.1) | 104.0 (87.8–117.2) | <0.01 | 103.4 (87.4–116.1) | 0.02 | 102 (85.8–115.0) | 0.9 |

| % Biologically Related | 5.5 | 53 | <0.001 | 0 | <0.001 | 0 | <0.001 |

Donor Characteristics

Donor demographics are also provided in Table 2 compared to the same three control populations. The median NKR donor age of 45 years (IQR 35–53) was similar to the UNOS LUR and other KPD donors, but three years older than all UNOS LD donors (p < 0.001). The NKR had a similar proportion of female donors 62.3% compared to the control populations (62.1%, 64.4%, and 61.8%, respectively). The proportion of NKR donors that were black (10.5%), was similar to all UNOS living donors (11.1%, p=0.4), but significantly greater than all UNOS LUR (7.7%, p<0.001) and all UNOS KPD (7.5%, p <0.001). The proportion of NKR Hispanic donors (10.1%) was similar to all UNOS LUR (10.5%) and all UNOS KPD (10.1%) donors, but significantly less than all UNOS living donors (14.4%, p <0.001). Only 2.2% of the NKR transplants were ABO incompatible (ABOi), but similar to the three controls (1.6%, 1.8%, and 2.2% respectively). Of these 46 NKR ABOi donors 32 were A to O (29 A2 to O); A to B=2; B to A=1; B to O=4; AB to A=2; and AB to B=5.

At the present time about 53% of all live donor kidney transplants in the US are performed using biologically related donors. Controls 2 and 3 were selected for only living unrelated donor recipient transplants. The NKR cohort included 5.5% that were biologically related pairs, which most often represented local loops or chain ends.

The BMI of the NKR donors 26.2 kg/m2 was essentially the same as the three controls 26.7, 26.6, and 26.3 kg/m2, respectively. In addition, the median eGFR of the NKR donors 102.2 cc/min. was similar to all UNOS LUR donors 103.4 cc/min. and all UNOS KPD donors 101.9 cc/min., but slightly lower than all UNOS donors 104 cc/min. (p <0.01). For NKR donors the 24-hour urine protein excretion ranged between undetectable to 252 mg/day. The left kidney was donated in 89.4% of transplants and the right 10.5%. There were 21% two and 2% three renal artery kidneys donated.

NKR Transplants

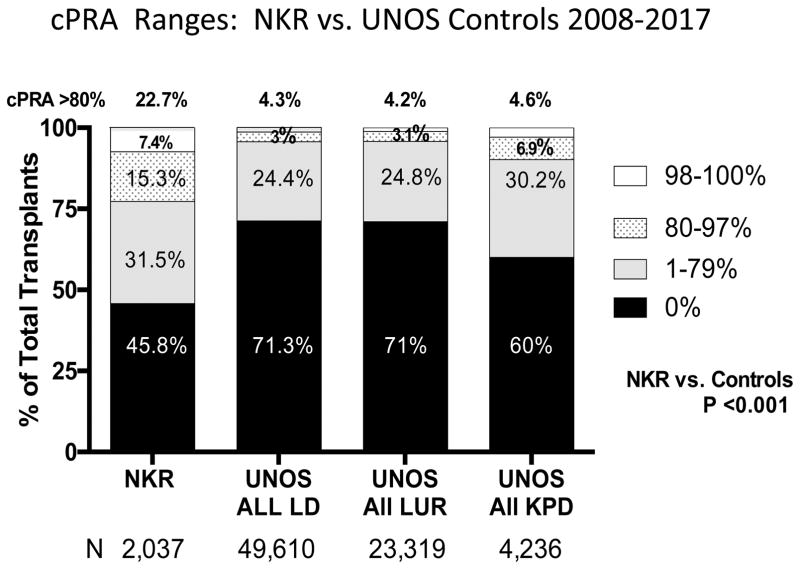

The NKR transplants were performed on a significantly greater proportion of HLA hyperimmunized patients, Figure 3 and Table 1. Only 45.8% of the NKR recipients had a pretransplant cPRA of zero, while the control populations represented 71.3%, 71%, and 60% unsensitized recipients (p <0.001). The NKR transplants representing the hard to match cPRA ranges of 80–97%, were accomplished for 15.3% of the recipients, while the three controls represented only 3%, 3.1%, and 6.9% (p <0.001). Only 0.8% of the NKR transplants were between zero HLA mismatched pairs, which was significantly fewer than all UNOS LD transplants 7.3% (p <0.001). The NKR transplants representing the extremely hard to match cPRA >98%, were accomplished for 7.4% of the recipients, while the three controls represented only 1.3%, 1.1%, and 2.9% (p <0.001). In summary, 22.7% of the NKR transplants were done in hard and/or extremely hard to match recipients; recalling that these patients had not received a zero mis-matched deceased donor kidney from the UNOS national sharing program as well.

Figure 3.

The distribution of cPRA at transplant for NKR kidney recipients vs. recipients of UNOS all live donors, UNOS living unrelated donors, and UNOS KPD donors.

Among the 2,037 NKR transplants 11.7% were reported to have undergone desensitization by the transplant centers; 222 for donor specific crossmatch activity and 17 for ABOi. The treatments employed for desensitization are represented in Table 3. While the use of intravenous immunoglobulins and plasmapheresis were the most common interventions, the doses and timing of the various agents utilized were not recorded in the NKR database. In addition, the stringency of the incompatibilities or the specific post-transplant management protocols employed by the centers were not available.

Table 3.

Methods of Desensitization used by NKR transplant centers for ABO and/or HLA incompatible Recipients. 2,037 Recipients over 9 years.

| Treatment | Number of Patients Given Each Therapy |

|---|---|

| I.V. Immunoglobulin/CMV-IG | 207 |

| Plasmapheresis | 86 |

| Thymoglobulin | 51 |

| Bortezomib | 6 |

| Rituximab | 39 |

| Eculizumab | 4 |

| Splenectomy | 1 |

Between the starting and ending dates of this study there were 59 donor-recipient pairs enrolled and transplanted as compatible pairs. The reasons given for entering paired exchange were to receive a younger aged kidney 27%; receive a larger kidney 21%; overcome low level DSA 13%; receive a better HLA match 22 %; avoid complex donor kidney anatomy 5%; and to help more patients (altruism) 12%. Among the enrolled compatible pairs 37% were biologically related; 32% were spouses, and 31% were unrelated. More important, of these compatible pairs 82% of the donors were blood group O, enrolling an additional 48 into the matching pool. For the compatible pairs the mean age (yrs.) for donors was 49.2; for recipients was 38.9, and for actual kidney donors was 40.1. For those seeking a younger donor as the reason to enter as a compatible pair the mean age difference between the paired and actual donors was 23.1 (range 11–42) years. The remaining pairs seeking anatomical or HLA advantage, or the absence of DSA, were successfully matched. By entering these compatible pairs 146 additional transplants were facilitated, and of these 43 recipients were transplanted with a cPRA >80%.

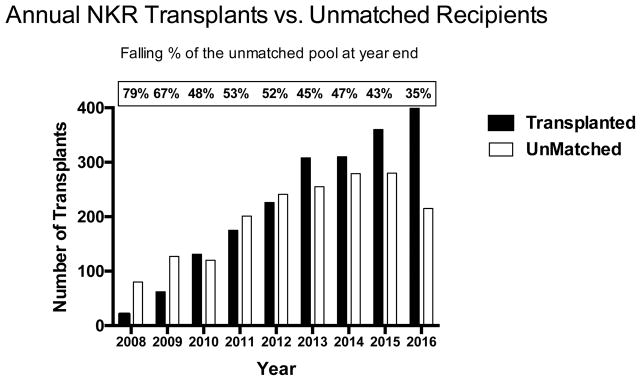

UnTransplanted Patients

When reporting actual KPD results it is important to identify who was not transplanted once entered into paired exchange. At the end of February 2017 there were 280 unmatched recipients active for transplant. Not surprisingly, the majority were blood group O and were hyperimmunized. The actual distribution was ABO: O (74%); A (14%); B (11%); and AB (1%). Those unmatched by cPRA% were: 0 (23%); 1–79 (22%); 80–95 (8%); 95–99 (18%); and 100 (29%). A better metric for tracking the accumulation of those recipients difficult to match for transplant may be the number of untransplanted recipients as a % of those actually transplanted at the end of each calendar year. As provided in Figure 4 since inception NKR has experienced a peak in unmatched recipients in year two (79%) that has fallen but leveled off at 35–40% during the last three years. In addition, the number of broken chains has diminished each year to about 3% annually, Table 4. These often occur after the logistics for a swap have been made, but intervening conditions such as a change in donor or recipient medical status emerges. Some of these can be repaired by bridging a donor or with advanced donation [14]. More worrisome, but infrequent, are the number of real time swap failures occurring after swaps have commenced on the day of exchanges. Since inception of the NKR program there have been 8 (0.4%). These real time swap failures were repaired within the network by end of chain paybacks according to established policy [8, 15].

Figure 4.

End of year number of actual NKR transplants vs. those unmatched candidates remaining in the pool.

Table 4.

Broken Chains Each Year

| Year | Bridge Donors | Broken Chains | % Broken per Year | Real Time Swap Failures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 9 | 3 | 33% | 0 |

| 2009 | 29 | 2 | 7% | 1 |

| 2010 | 61 | 2 | 3% | 0 |

| 2011 | 75 | 0 | 0% | 0 |

| 2012 | 54 | 4 | 7% | 0 |

| 2013 | 37 | 3 | 8% | 3 |

| 2014 | 49 | 4 | 8% | 2 |

| 2015 | 53 | 1 | 2% | 1 |

| 2016 | 68 | 2 | 3% | 1 |

| 2017 | 64 | 1 | 3% | 0 |

| Totals | 499 | 22 | 8 (0.4%) |

Discussion

During the last 15 years there has been a substantial effort to increase live donor kidney transplantation through KPD, beginning as single center internal swaps to organized networks such as the NKR [3–7, 16, 17]. These swaps have primarily been composed of 2– 3 or more simultaneous exchanges (loops), and non-simultaneous chains driven by non-directed donors. As reported to UNOS national KPD numbers have increased from less than 10 in 2002, to 450 in 2010, to 587 in 2015 to 642 in 2016 [18]. The underlying motivation for this effort is to transplant more recipients with compatible live donor kidneys, which have been demonstrated to result in less delayed graft function, better measured kidney function, longer graft survival, and to diminish deceased donor candidate rolls [18, 19]. The NKR is a voluntary program available to transplant centers governed by a Medical Board that establishes rules for sharing kidneys that are compliant with current national regulations and policies for living kidney donation and transplantation. These regulations and sharing paradigms are transparent and publically available at https://kidneyregistry.org/transplant_center.php#policies).

The evolution of the NKR has been a continual process of introducing innovations and solutions to problems as they arise to ensure an efficient workflow. These advances are first suggested; then modeled in small test series; then validated in real time practice; and finally approved by the NKR Medical Board. Once implemented new policies are posted on the NKR website and educational programs are provided for the member centers. Five examples of major policy changes that have streamlined the practice of KPD and removed logistical barriers that delayed or cancelled actual transplants are the following. First, the use of a donor pre-select function on the website to accept or decline all potential donors in the pool for a newly enrolled recipient. By excluding donors with anatomical, physiological, or immunological incompatibilities, undesirable matches are avoided by centers that could disrupt chains. Second, the implementation of a cryopreserved bank of donor cells for each enrolled kidney donor. This permits repetitive cross matching and exploratory cross matching of highly sensitized recipients without depending on the acquisition additional blood from donors. Third, the introduction of large server capacity to store all donor CT scan imaging on the website, available when kidney donors are first enrolled. This permits rapid decision making by recipient centers as to donor anatomy and acceptability when the matches are first made. Duplicate imaging, separate consent for imaging, time for shipping images, etc. is thus eliminated. Discussions between donor and recipient surgeons is also facilitated. Fourth, the introduction of the Advanced Donation and Voucher programs have permitted the repair of many short-term chain disruptions and helped support donors in completing their individual decisions to proceed with kidney donation (14, 31). Fifth, applying strict deadlines for logistic calls and kick off calls between the centers and the NKR facilitators in order to detect and repair any disruptions as the swaps unfold.

An important feature of NKR is the participation of small, medium, and large kidney transplant programs in all regions of the United States. The participating centers also represent densely urban, suburban, and rural populations, and both academic and community based programs that include a broad spectrum of donors, recipients and clinical practices. Therefore, is the population of patients transplanted through the NKR in some way different or narrowly selected compared to other live donor transplants at the current time? Are changes needed to detect and manage discrepancies or the lack of opportunities for potential recipients and donors?

The answer to these questions appears to be no (Table 2). The demographics of the NKR recipients and donors demonstrate similar diversity to the overall numbers in the United States for all live donor transplants, for all LUR transplants, and for other KPD exchanges. In particular, the proportion of patients that are older aged, female, racial minorities, or those on public insurance are similar or over represented in the NKR compared to the other control populations used in this study. This is perhaps not surprising considering the inclusion of transplant centers from all geographic regions and population density previously mentioned. It would appear that the same clinical selection criteria and financial screening practices that govern in-center live donor kidney transplantation apply to KPD on a national level [10]. It is important to emphasize that selection criteria and eligibility characteristics for donors and recipients are made by each transplant center, not by a centralized body. No group of ESRD patients appear to be restricted from the opportunity for paired exchange.

The characteristics for the actual NKR kidney donors also do not appear to be substantially different from the national controls (Table 2). The median age, BMI, eGFR, % females and minorities, were all within similar clinical ranges. Although a few statistical differences emerged between black donors NKR 10.5% vs. all LUR 7.7%, p <0.001 and fewer female donors NKR 62.3% vs. all LUR 65.4%, P <0.01.

The results reported here would suggest that the NKR is actually transplanting a somewhat more difficult to match population of recipients. The NKR recipients represented a significantly (p < 0.001) increased number of retransplants 25.6% compared to the controls (11.5, 12.3. 16.1%), even though the number of pre-emptive (dialysis-free) transplants of 35% are about the same. While comparing the risk for medical morbidity is limited in such a registry analysis, surrogate markers such as % diabetics, hypertensives, hepatitis C disease, and age were about the same for all groups. The reported outcomes for the NKR transplants equaled or exceeded the control groups for all cause graft survival, Figure 2. This may be explained by the fact that the majority of NKR transplants were both ABO compatible and HLA crossmatch negative. When KPD exchanges produce compatible transplants, excellent results have been reported in both the US and other parts of the world [7, 20–23]. In addition, as recently reported in depth, the shipping of kidneys during paired exchange has not been associated with inferior transplant outcomes [24]. Although the number with primary non-function, 0.34% was low, the numbers with first week dialysis 4.9% is higher than in-center exchanges. Some have suggested that live donor kidneys >55 years of age may be more susceptible to extra cold ischemia times [25].

As reported in Figure 3, the NKR recipients were significantly (P <0.001) more sensitized to HLA, perhaps related to the greater numbers of retransplants, than the controls. Notably, 22.7% of NKR recipients had a cPRA >80%, 7.4% >98%, and 2.5% were both blood group O and had a cPRA >98%. Many of these recipients were unable to find a suitable deceased donor kidney as well. While HLA sensitization leading to donor specific crossmatch reactivity is a primary indication to enter paired exchange, it is also a leading indicator of waiting time once enrolled. The NKR has not intentionally limited or discouraged entering highly sensitized recipients into the network. While the number of KPD transplants that were ABOi 2.2% (excluding A2 into O), or were intentionally desensitized 11.7%, were not common, this may be an area for future growth [26, 27].

Some have speculated that the accumulation of hyperimmunized O recipients with non-O donors will overwhelm paired exchange networks [28], but these concerns appear to be unwarranted, Figure 4. The unmatched pool of candidates at years end has in fact declined to about 35–40% of those transplanted, although the predominant characteristics of those unmatched candidates were 74% ABO blood type O, and 29% cPRA=100%. While the difficulty to find donors for these hard to match recipients has thus far depended on the entry of blood type O non-directed donors for chain initiation, future expansion of KPD via increasing network pool sizes, compatible pair enrollments [9], the possibility of deceased donor chain initiation [29], and global sharing [30] may further expand these opportunities.

The limitations of this study are similar to those present in any registry-based analysis. While some data were not collected or lacked granularity, by merging both the national and local (NKR) datasets, we were able to capture a wide array of relevant covariates. Although such a merge may be redundant for some variables (i.e. race, gender, insurance), it reduced missing data to <2% for each category. On a center level, it is not known how many potential KPD patients were evaluated and ultimately excluded based on local medical or psychosocial criteria. There were certainly center level decisions made for donor acceptance criteria such as the degree of allosensitization, or anatomic or physiologic risk/benefit determinations for a particular swap.

In conclusion, the practice of KPD in general and the NKR network in particular is expanding annually, offering the opportunity for compatible live donor kidney transplantation to more patients. The demographic and clinical characteristics of those actually transplanted appear similar with contemporary national trends. However, analysis such as this do not fully capture the enormous number of logistic considerations that need to be accommodated between patients, families, and transplant centers. These results encourage broader sharing and larger pool sizes in order to unlock more opportunities for those harder to match pairs.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK); grant numbers F30DK116658 (PI: Ashton Shaffer), K01DK114388 (PI: Macey Henderson), and K24DK101828 (PI: Dorry Segev).

Abbreviations

- ABOi

ABO incompatibility

- CIT

cold ischemia time

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- KPD

kidney paired donation

- NKR

National Kidney Registry

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

References

- 1.Rapaport FT. The case for a living emotionally related international kidney donor exchange registry. Transplant Proc. 1986;18:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terasaki PI, Cecka JM, Gjertson DW, Takemoto S. High survival rates of kidney transplants from spousal and living unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(6):333–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508103330601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery RA, Zachary AA, Ratner LE, Segev DL, Hiller JM, Houp J, et al. Clinical results from transplanting incompatible live kidney donor/recipient pairs using kidney paired donation. JAMA. 2005 Oct 5;294(13):1655–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.13.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth AE, Sonmez T, Unver MU, Delmonico FL, Saidman SL. Utilizing list exchange and non-directed donation through ‘chain’ paired kidney donations. Am J Transplant. 2006 Nov;6(11):2694–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpkins CE, Montgomery RA, Hawxby AM, et al. Cold ischemia time and allograft outcomes in live donor renal transplantation: Is live donor organ transport feasible? Am J Transplant. 2007;7:99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melcher ML, Leeser DB, Gritsch HA, Milner J, Kapur S, Busque S, et al. Chain transplantation: initial experience of a large multicenter program. Am J Transplant. 2012 Sep;12(9):2429–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole EH, Nickerson P, Campbell P, Yetzer K, Lahaie N, Zaltzman J, et al. The Canadian kidney paired donation program: a national program to increase living donor transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99(5):985–90. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [Accessed December 31, 2017];The National Kidney Registry. https://kidneyregistry.org/transplant_center.php#policies.

- 9.Cuffy M, Ratner L, Siegler M, Woodle ES. Equipoise: ethical, scientific, and clinical trial design considerations for compatible pair participation in kidney exchange programs. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(6):1484–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1200/optn_policies.pdf#nameddest=Policy_08

- 11.LaPointe RD, Hays R, Baliga P, Cohen DJ, Cooper M, Danovitch GM, et al. Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: recommendations to optimize education, access, and care. Am J Transplant. 2015 Apr;15(4):914–22. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reese PP, Boudville N, Garg AX. Living kidney donation: outcomes, ethics, and uncertainty. Lancet. 2015 May 16;385(9981):2003–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62484-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massie AB, Kuricka LM, Segev DL. Big Data in Organ Transplantation: Registries and Administrative Claims. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:1723–30. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flechner SM, Leeser D, Pelletier R, Morgievich M, Miller K, Thompson L, McGuire S, Sinacore J, Hil G. The Incorporation of an Advanced Donation Program into Kidney Paired Exchange: initial experience of the National Kidney Registry. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(10):2712–17. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowan N, Gritsch H, Nassiri N, Sinacore J, Veale J. Broken Chains and Reneging: A Review of 1748 Kidney Paired Donation Transplants. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:2451–57. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bingaman AW, Wright FH, Jr, Kapturczak M, Shen L, Vick S, Murphey CL. Single-center kidney paired donation: the Methodist San Antonio experience. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(8):2125–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gentry SE, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Kidney paired donation: fundamentals, limitations, and expansions. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(1):144–51. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data#

- 19.Matas AJ, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Thompson B, Gustafson SK, Schnitzler MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2012 Annual Data Report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(Suppl 1):11–44. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park K, Moon JI, Kim SI, Kim YS. Exchange Donor Program in Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;67(2):336–38. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199901270-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantwell L, Woodroffe C, Holdsworth R, Ferrari P. Four years of experience with the Australian kidney paired donation programme. Nephrology. 2015;20(3):124–31. doi: 10.1111/nep.12369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jha PK, Sethi S, Bansai SB, et al. Paired Kidney Exchange Transplantation: Maximizing the donor pool. Indian J Nephrol. 2015;25(6):349–354. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.150721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kute VB, Patel HV, Shah PR, et al. Impact of single center kidney paired donation transplantation to increase donor pool in India: a cohort study. Transplantation International. 2017;30:679–688. doi: 10.1111/tri.12956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treat E, Chow E, Peipert J, Waterman A, Kwan L, Massie AB, Thomas A, Leeser D, Flechner SM, Melcher M, Kapur S, Segev D, Veale J. Shipping Living Donor Kidneys and Transplant Recipient Outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2017 Nov 22; doi: 10.1111/ajt.14597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnan AR, Wong G, Chapman JR, et al. Prolonged Ischemic Time, Delayed Graft Function, and Graft and Patient Outcomes in Live Donor Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant. 2016;9:2714–23. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montgomery RA, Lonze BE, Jackson AM. Using donor exchange paradigms with desensitization to enhance transplant rates among highly sensitized patients. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2011 Aug;16(4):439–43. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32834897c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orandi BJ, Luo X, Massie AB, Garonzik-Wang JM, Lonze BE, Ahmed R, et al. Survival Benefit with Kidney Transplants from HLA-Incompatible Live Donors. N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 10;374(10):940–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Stegall MD, Dean PG, Casey ET, Reddy KS, Khamash HA, et al. Assessing the efficacy of kidney paired donation--performance of an integrated three-site program. Transplantation. 2014;98(3):300–5. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melcher ML, Roberts JP, Leichtman AB, Roth AE, Rees MA. Utilization of Deceased Donor Kidneys to Initiate Living Donor Chains. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(5):1367–70. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connolly JS, Terasaki PI, Veale JL. Paired Donation-the Next Step. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:868–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1106996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veale JL, Capron AM, Nassiri N, Danovitch G, et al. Vouchers for Future Kidney Transplants to Overcome “Chronological Incompatibility” Between Living Donors and Recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101:2115–2119. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]