Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that hemoglobin concentration after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is associated with neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest in patients treated with targeted temperature management.

Methods

We studied consecutive adult patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest treated with targeted temperature management between January 2009 and December 2015. We investigated the association between post ROSC hemoglobin concentrations and good neurologic outcome (defined as Cerebral Performance Category of 1 and 2) at hospital discharge using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

A total of 246 subjects were ultimately included in this study. The mean age was 54 years (standard deviation, 17); 168 (68%) subjects were male. Eighty-seven (35%) subjects had a good neurologic outcome at hospital discharge. Hemoglobin concentrations were higher in the good outcome group than in the poor outcome group (14.4±2.0 vs. 12.8±2.5 g/dL, P<0.001). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that hemoglobin concentrations were associated with good neurologic outcome at hospital discharge after adjusting for other confounding factors (adjusted odds ratio, 1.186; 95% confidence interval, 1.008 to 1.395).

Conclusion

In post ROSC patients, hemoglobin concentrations after ROSC were associated with neurologic outcome at hospital discharge.

Keywords: Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; Hemoglobin; Neurologic outcome; Hypothermia, induced

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac arrest (CA) is a worldwide major public health problem and the survival rate of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is still low [1,2]. Hypoxic ischemic brain injury is a major cause of morbidity and mortality of postcardiac arrest syndrome (PCAS). While the optimal target temperature is unknown, targeted temperature management (TTM) is well known to improve survival and neurologic outcome after CA [3-5]. In addition to TTM, the optimal PCAS care should include comprehensive packages of intensive care treatment such as early percutaneous intervention, hemodynamic optimization, oxygenation and ventilation strategies, glucose management, and seizure detection and treatment to prevent secondary injury [6-8]. Therefore, appropriate strategies and goals of optimal PCAS care should be further studied.

An imbalance between oxygen delivery and cerebral metabolic demand could worsen ischemic-reperfusion injury and lead to irreversible cell death. However, optimal cerebral oxygen delivery during PCAS care is currently unknown. The hemoglobin concentration is an essential component of oxygen delivery. Low hemoglobin concentration can impair the neurologic outcome by affecting oxygen delivery. Recent studies have demonstrated that hemoglobin levels were associated with neurologic outcome after CA [9-11]. However, previous studies on hemoglobin’s effect on that outcome have included both patients receiving TTM and those who did not. Therefore, it is necessary to demonstrate the association between hemoglobin levels and neurologic outcome after CA in those patients treated with TTM, because TTM is generally considered as the standard of care after CA.

The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that hemoglobin levels after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) are associated with neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest in patients treated with TTM.

METHODS

Patients and setting

We performed a retrospective observational study using prospectively collected data from a single tertiary educational hospital in Seoul, Korea between January 2009 and December 2015. Our hospital is a 1,350-bed tertiary care referral center that maintains a prospective database for all post OHCA patients. The inclusion criteria were patients who were older than 18 years of age, were resuscitated from OHCA, and were treated with TTM. Patients were excluded if hemorrhage such as gastrointestinal bleeding or intracranial bleeding was suspected as an etiology of their CA. This study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital, and a waiver of consent was allowed because of the retrospective nature of the study (FN: KC16RISI0670).

Postcardiac arrest care

All comatose patients who were resuscitated after CA were eligible for TTM according to our previously published postcardiac arrest care protocols [12]. An endovascular cooling device (CoolGard Thermal Regulation System; Alsius Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA) or ArticSun (Bard Medical, Louisville, CO, USA) was used to induce a target temperature of 33°C. The target temperature was maintained at least for 24 hours. After 24 hours at 33°C, the patients were slowly rewarmed to 37°C at a rate of 0.25°C/hr. An arterial line was routinely inserted into a radial artery to monitor the blood pressure and obtain blood samples.

Data collection

The following patient variables were abstracted: age; sex; history of hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease, end stage renal disease on hemodialysis, liver cirrhosis, and malignancy; witnessed arrest; bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation; first monitored rhythm; cause of arrest; time from collapse to ROSC; and glucose and hemoglobin concentration immediately after ROSC. The primary outcome was good neurologic status at hospital discharge defined as the Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) scores of 1 to 2 [13]. Patients were dichotomized into “good outcome” (CPC 1 to 2) and “poor outcome” (CPC 3 to 5).

Statistical analysis

Fisher exact test and the chi-square test for categorical variables, the t-test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables were used for patient characteristics and comparisons between outcome groups based on the results of normality testing. The continuous data were presented as the means±standard deviation or median (interquartile range) and categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages. Univariate analyses were performed to test the association between each variable and poor neurologic outcome at hospital discharge. Variables with P-values <0.200 in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate logistic regression model. The factors with P-values <0.05 on the multivariate logistic regression model were considered as adjusted variables. Finally, history of HTN, time from collapse to ROSC, and initial shockable rhythm were selected as adjusted variables. To evaluate the association of hemoglobin concentration with good neurologic outcome at hospital discharge, hemoglobin concentrations were divided into quintiles using the following cutoff values: ≤11.2, 11.3–12.9, 13.0–14.1, 14.2–15.4, and ≥15.5 g/dL. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with the lowest quintile as the reference. The hemoglobin concentration was examined as a continuous variable as well. We estimated receiver operating characteristic curves and compared the areas under the curves (C-statistic with 95% CI) in corresponding logistic models. Data were analyzed using the PASW Statistics ver. 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Four hundred nineteen patients with ROSC after CA were admitted to our emergency department during the study period. One hundred seventy three patients were excluded because they were not treated with TTM. A total of 246 patients were finally included in this study. Of these, 87 patients had a good neurologic outcome at hospital discharge. The respective mean ages of the good and poor outcome groups were 48.3±15.8 and 56.4±16.5 years (P<0.001). Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the patients according to neurologic outcome. The hemoglobin concentration after ROSC was higher in the good outcome group than in the poor outcome group (14.4±2.0 vs. 12.8±2.5, P<0.001). When the hemoglobin was divided into quintiles, the higher the hemoglobin concentration, the higher the ratio of good outcome. The proportions of good outcome for each quintile were 12.5%, 23.5%, 33.3%, 55.1%, and 52%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the subjects

| Characteristics | Total (n = 246) | Good outcome (n = 87) | Poor outcome (n = 159) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 54 (43–68) | 48 (38–59) | 57 (44–70) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 168 (68.3) | 63 (72.4) | 105 (66.0) | 0.320 |

| Past history | ||||

| HTN | 70 (28.5) | 16 (18.4) | 54 (34.0) | 0.012 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 49 (19.9) | 6 (6.9) | 43 (27.0) | < 0.001 |

| CAD | 28 (11.4) | 11 (12.6) | 17 (10.7) | 0.677 |

| ESRD on HD | 13 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 13 (8.2) | 0.005 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.9) | 0.554 |

| Malignancy | 9 (3.7) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (5.0) | 0.165 |

| Witnessed arrest | 179 (72.8) | 75 (86.2) | 104 (65.4) | 0.001 |

| Bystander CPR | 141 (57.3) | 57 (65.5) | 84 (52.8) | 0.060 |

| Shockable rhythm | 94 (38.2) | 64 (73.6) | 30 (18.9) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac cause of arrest | 170 (69.1) | 78 (89.7) | 92 (57.9) | < 0.001 |

| Time from collapse to ROSC (min) | 30 (17–42) | 20 (11–32) | 34 (24–48.5) | < 0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 256 (188–321) | 231 (186–286) | 273 (189–338) | 0.069 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.4 ± 2.5 | 14.4 ± 2.0 | 12.8 ± 2.5 | < 0.001 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range), number (%), or mean±standard deviation.

HTN, hypertension; CAD, coronary artery disease; ESRD, end stage renal disease; HD, hemodialysis; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the subjects according to hemoglobin quintiles

| Characteristics | 1st quintile | 2nd quintile | 3rd quintile | 4th quintile | 5th quintile | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤11.2 g/dL (n = 48) | 11.3–12.9 g/dL (n = 51) | 13.0–14.1 g/dL (n = 48) | 14.2–15.4 g/dL (n = 49) | ≥15.5 g/dL (n = 50) | ||

| Mean age (yr) | 60.8 ± 15.1 | 60.6 ± 16.7 | 51.9 ± 16.9 | 52.0 ± 14.5 | 42.6 ± 13.1 | < 0.001 |

| Male | 25 (52.1) | 29 (56.9) | 30 (62.5) | 39 (79.6) | 45 (90.0) | < 0.001 |

| Past history | ||||||

| HTN | 14 (29.2) | 19 (37.3) | 15 (31.3) | 14 (28.6) | 8 (16.0) | 0.080 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (45.8) | 13 (25.5) | 3 (6.3) | 6 (12.2) | 5 (10.0) | < 0.001 |

| CAD | 6 (12.5) | 8 (15.7) | 4 (8.3) | 8 (16.3) | 2 (4.0) | 0.244 |

| ESRD on HD | 10 (20.8) | 3 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.005 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.554 |

| Malignancy | 4 (8.3) | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) | 0.165 |

| Witnessed arrest | 34 (70.8) | 37 (72.5) | 32 (66.7) | 40 (81.6) | 36 (72.0) | 0.575 |

| Bystander CPR | 29 (60.4) | 27 (52.9) | 25 (52.1) | 30 (61.2) | 30 (60.0) | 0.726 |

| Shockable rhythm | 7 (14.6) | 12 (23.5) | 16 (33.3) | 29 (59.2) | 30 (60.0) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac cause of arrest | 30 (62.5) | 33 (64.7) | 30 (62.5) | 39 (79.6) | 38 (76.0) | 0.045 |

| Time from collapse to ROSC (min) | 32.5 ± 17.4 | 33.5 ± 21.3 | 29.2 ± 19.8 | 28.7 ± 14.6 | 32.5 ± 19.8 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 275.7 ± 103.4 | 271.4 ± 158.3 | 273.9 ± 103.4 | 252.1 ± 98.6 | 251.8 ± 88.6 | 0.069 |

| Good outcome | 6 (12.5) | 12 (23.5) | 16 (33.3) | 27 (55.1) | 26 (52.0) | < 0.001 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

HTN, hypertension; CAD, coronary artery disease; ESRD, end stage renal disease; HD, hemodialysis; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

In the univariate analyses, age; history of HTN and diabetes mellitus; witnessed arrest; cardiac cause of arrest; time from collapse to ROSC; and shockable rhythm showed statistically significant associations with good neurologic outcome at hospital discharge. Variables with P-values <0.200 on univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate logistic regression model. History of HTN, time from collapse to ROSC and initial shockable rhythm were finally selected as adjusted variables (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis for factors associated with good neurologic outcome at hospital discharge

| Variable | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 0.970 | 0.954–0.986 | < 0.001 | 0.983 | 0.957–1.009 | 0.200 |

| Sex, male | 1.350 | 0.761–2.395 | 0.305 | |||

| Hypertension | 0.438 | 0.232–0.826 | 0.011 | 0.385 | 0.151–0.984 | 0.046 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.200 | 0.081–0.492 | < 0.001 | 0.438 | 0.145–1.320 | 0.143 |

| CAD | 0.827 | 0.369–1.856 | 0.645 | |||

| Witnessed arrest | 3.305 | 1.655–6.599 | 0.001 | 1.472 | 0.553–3.920 | 0.439 |

| Bystander CPR | 1.696 | 0.988–2.913 | 0.055 | 1.073 | 0.491–2.346 | 0.860 |

| Cardiac cause of arrest | 6.312 | 2.956–13.474 | < 0.001 | 2.678 | 0.976–7.345 | 0.056 |

| Time from collapse to ROSC | 0.956 | 0.938–0.973 | < 0.001 | 0.942 | 0.920–0.964 | < 0.001 |

| Shockable rhythm | 11.965 | 6.473–22.251 | < 0.001 | 9.842 | 4.128–23.462 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose | 0.998 | 0.996–1.001 | 0.200 | |||

| Hemoglobin | 1.352 | 1.191–1.535 | < 0.001 | 1.186 | 1.008–1.395 | |

| Hemoglobin, quintile | ||||||

| 1st quintile | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| 2nd quintile | 2.154 | 0.737–6.295 | 0.161 | 2.150 | 0.585–7.909 | |

| 3rd quintile | 3.500 | 1.231–9.951 | 0.019 | 2.813 | 0.793–9.969 | |

| 4th quintile | 8.591 | 3.085–23.920 | < 0.001 | 4.398 | 1.229–15.742 | |

| 5th quintile | 7.583 | 2.736–21.021 | < 0.001 | 3.870 | 1.042–14.372 | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CAD, coronary artery disease; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

After adjusting for history of HTN, time from collapse to ROSC, and initial shockable rhythm, hemoglobin concentrations were associated with good neurologic outcome at hospital discharge. Patients in the 4th quintile of hemoglobin were 4.398 times more likely to have a good neurologic outcome compared with those in the lowest quintile of hemoglobin (Table 3). The adjusted ORs for 5th quintile was 3.870 (95% CI, 1.042 to 14.372). When examined as a continuous variable, hemoglobin concentrations after ROSC still showed an association with good neurologic outcome at hospital discharge (adjusted OR, 1.186; 95% CI, 1.008 to 1.395).

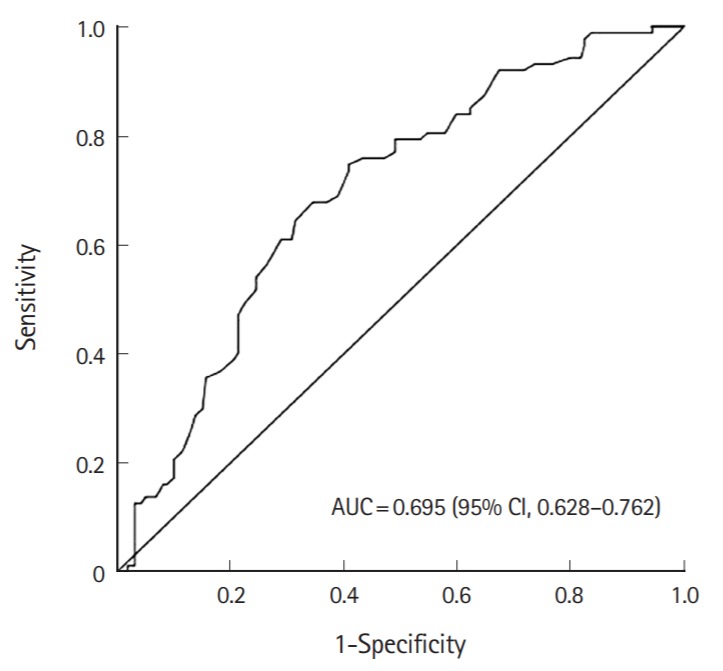

The association between different post ROSC hemoglobin levels and good neurological outcome at hospital discharge was assessed using the receiver operating characteristic curve. The area under the curve was 0.695 (95% CI, 0.628 to 0.712) and a post ROSC hemoglobin level >13.3 g/dL had a sensitivity of 74.7% and specificity of 59.1% for predicting good outcome (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for hemoglobin concentration for prediction of good neurologic outcome at hospital discharge. AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this retrospective cohort study is that hemoglobin concentrations after ROSC are associated with neurologic outcome at hospital discharge. The results of this study were similar to previous studies that have included both patients receiving TTM and those who did not.

Optimal cerebral oxygen delivery is critical to the injured brain. Oxygen delivery is determined by cardiac output and arterial oxygen content, which is dependent on hemoglobin concentration, oxygen saturation and partial pressure of arterial oxygen. There is a slight debate, but some observational studies have demonstrated that supranormal arterial oxygen tension could worsen outcome after CA [14-19]. The main detrimental effect of hyperoxia after CA is due to the increased reactive oxygen species and vasoconstriction of cerebral blood vessels [20-22]. Therefore, a strategy is needed to optimize oxygen delivery while avoiding the deleterious effects of hyperoxia. However, the most effective way to minimize oxidative damage while optimizing oxygen delivery is not yet known and should be further studied.

There is no specific study indicating that increasing hemoglobin concentration could improve neurologic outcome in patients with CA. However, hemoglobin concentration has been studied in several populations of critically ill patients [23-26]. Most studies stated that a restrictive strategy of red cell transfusion is similar to a liberal transfusion strategy except in acute myocardial infarction. Thus, transfusions are generally accepted when the hemoglobin concentration is below 7 g/dL in non-bleeding critically ill patients. However, it is questionable whether this transfusion strategy should be applied equally to post CA patients. In our cohort, the good outcome rate of the first quintile of hemoglobin concentration is lowest among the five quintiles. Moreover, the 3 patients with hemoglobin less than 7 g/dL all died during their hospital stay. Furthermore, of the 25 patients with hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL only one patient survived. However, since transfusion was not investigated in this study, the effect of transfusion requires further investigation.

There have been some studies on hemoglobin concentration and outcome after CA [23-27]. Previous studies have consistently asserted that there is a relationship between hemoglobin concentration and outcome after CA, which is the same as in our study. However, most previous studies have included both patients receiving TTM and those who did not. The rate of patients with hemoglobin concentration less than 10 g/dL is significantly different between the study from Albaeni et al. [11] and our study (33% vs. 10%, respectively). Patients who were not treated with TTM are likely to have more comorbidities and this could be a potential bias. Therefore, we excluded the patients not treated with TTM. Nonetheless, hemoglobin concentration was associated with neurologic outcome, which is evidence that cerebral oxygenation is an important factor to improve outcome in patients after CA.

Ameloot et al. [27] demonstrated that hemoglobin concentration had a strong linear relationship with mean cerebral oxygenation and hemoglobin concentration below 10 g/dL generally resulted in lower cerebral oxygenation. They also suggested that hemoglobin concentration below 12.3 g/dL during the 1st day of intensive care unit stay were associated with worse outcome after CA. The compensatory mechanism in post CA patients may be insufficient and anemia could aggravate the ischemic-reperfusion brain injury at higher hemoglobin thresholds [28]. Additionally, the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve shifted leftward during therapeutic hypothermia. Thus, cerebral oxygenation depends even more on hemoglobin concentration.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a single-center study, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Second, this is a retrospective study that should be confirmed by a larger prospective multicenter study. Third, most of our patients were managed with therapeutic hypothermia at 33°C, irrespective of their initial rhythm. Therefore, our findings may not apply to patients who are treated with different management strategies. Fourth, only hemoglobin concentration at the time of admission was examined. Moreover, the impact of transfusion on patient survival is still unknown because transfusion during hospital stay was not investigated. This is major limitation of this study; the effect of transfusions should be further explored.

In conclusion, hemoglobin concentrations after ROSC are associated with neurologic outcome at hospital discharge. Future research to examine the association between hemoglobin levels and neurologic outcome after CA is warranted.

Capsule Summary

What is already known

Hemoglobin concentration is associated with outcome after cardiac arrest. Transfusion is generally indicated in non-bleeding critically ill patients with a hemoglobin concentration of <7 g/dL

What is new in the current study

Hemoglobin concentration is associated with neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest in patients treated with targeted temperature management.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2016 update. A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn KO, Shin SD, Suh GJ, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes from non-traumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Korea: a nationwide observational study. Resuscitation. 2010;81:974–81. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:549–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:557–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, et al. Targeted temperature management at 33°C versus 36°C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2197–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunde K, Pytte M, Jacobsen D, et al. Implementation of a standardised treatment protocol for post resuscitation care after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2007;73:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaieski DF, Fuchs B, Carr BG, et al. Practical implementation of therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Hosp Pract (1995) 2009;37:71–83. doi: 10.3810/hp.2009.12.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callaway CW, Donnino MW, Fink EL, et al. Part 8: post-cardiac arrest care. 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132(18 Suppl 2):S465–82. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wormsbecker A, Sekhon MS, Griesdale DE, Wiskar K, Rush B. The association between anemia and neurological outcome in hypoxic ischemic brain injury after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2017;112:11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson NJ, Rosselot B, Perman SM, et al. The association between hemoglobin concentration and neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. J Crit Care. 2016;36:218–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albaeni A, Eid SM, Akinyele B, Kurup LN, Vaidya D, Chandra-Strobos N. The association between post resuscitation hemoglobin level and survival with good neurological outcome following out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;99:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youn CS, Kim SH, Oh SH, Kim YM, Kim HJ, Park KN. Successful implementation of comprehensive packages of postcardiac arrest care after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a single institution experience in South Korea. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag. 2013;3:17–23. doi: 10.1089/ther.2012.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rittenberger JC, Raina K, Holm MB, Kim YJ, Callaway CW. Association between Cerebral Performance Category, Modified Rankin Scale, and discharge disposition after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1036–40. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilgannon JH, Jones AE, Shapiro NI, et al. Association between arterial hyperoxia following resuscitation from cardiac arrest and in-hospital mortality. JAMA. 2010;303:2165–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilgannon JH, Jones AE, Parrillo JE, et al. Relationship between supranormal oxygen tension and outcome after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2011;123:2717–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janz DR, Hollenbeck RD, Pollock JS, McPherson JA, Rice TW. Hyperoxia is associated with increased mortality in patients treated with mild therapeutic hypothermia after sudden cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:3135–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182656976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee BK, Jeung KW, Lee HY, et al. Association between mean arterial blood gas tension and outcome in cardiac arrest patients treated with therapeutic hypothermia. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elmer J, Scutella M, Pullalarevu R, et al. The association between hyperoxia and patient outcomes after cardiac arrest: analysis of a high-resolution database. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3555-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmerhorst HJ, Roos-Blom MJ, van Westerloo DJ, de Jonge E. Association between arterial hyperoxia and outcome in subsets of critical illness: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of cohort studies. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1508–19. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Globus MY, Busto R, Lin B, Schnippering H, Ginsberg MD. Detection of free radical activity during transient global ischemia and recirculation: effects of intraischemic brain temperature modulation. J Neurochem. 1995;65:1250–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazelton JL, Balan I, Elmer GI, et al. Hyperoxic reperfusion after global cerebral ischemia promotes inflammation and long-term hippocampal neuronal death. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:753–62. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornet AD, Kooter AJ, Peters MJ, Smulders YM. The potential harm of oxygen therapy in medical emergencies. Crit Care. 2013;17:313. doi: 10.1186/cc12554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy GJ, Pike K, Rogers CA, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:997–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holst LB, Haase N, Wetterslev J, et al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1381–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ameloot K, Genbrugge C, Meex I, et al. Low hemoglobin levels are associated with lower cerebral saturations and poor outcome after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2015;96:280–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hare GM, Mazer CD, Hutchison JS, et al. Severe hemodilutional anemia increases cerebral tissue injury following acute neurotrauma. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;103:1021–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01315.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]