Abstract

Gynecomastia refers to an enlargement of the male breast caused by benign proliferation of the glands ducts and stromal components including fat. It is the most common form of breast swelling seen in adolescent males. During pubertal development, gynecomastia can develop as a result of transient relative imbalances between androgens and estrogens. Pubertal gynecomastia is self-limited in 75 to 90% of adolescents and regresses over 1 to 3 years. However it may cause significant psychological stress and depression in adolescents. For boys with persistent gynecomastia that is causing substantial tenderness or embarrassment a tailored approach of close follow-up and use of anti-estrogen drugs may be recommended. These drugs block the effects of estrogens in the body and can reduce the size of the breasts somewhat. It appears that pharmacological therapy of persistent adolescent gynecomastia is reasonable effective if given early in the course of the disease and more successful in cases with small or moderate breast enlargement. However, neither of these drugs is universally approved for the treatment of gynecomastia because the risks and benefits have not been studied completely. Surgical approach may be needed under special conditions for cosmetic reasons. In this update, we review the different published trials for managing adolescent gynecomastia. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: gynecomastia, adolescents, androgens, estrogens, anti-estrogen drugs, mammary adenectomy, liposuction

Introduction

Adolescent gynecomastia is defined as a benign glandular proliferation in the male breast and is derived from the Greek terms gynec (female) and mastos (breast). The condition may be unilateral or bilateral, acute or chronic, with or without tenderness on touch (mastalgia). It should be differentiated from pseudo gynecomastia (fatty breasts) which is commonly seen in obese males due to increased fat deposition without glandular proliferation. Gynecomastia may cause significant embarrassment and emotional distress in adolescent males. In this article, the authors focus on management of adolescent gynecomastia both from the medical and surgical lines (1, 2).

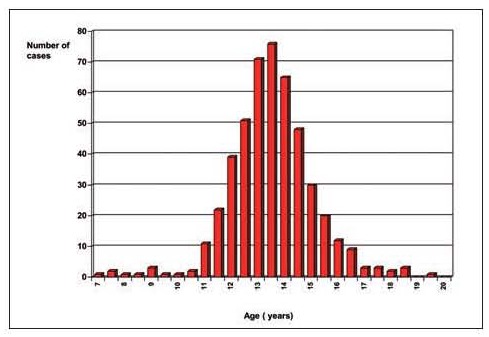

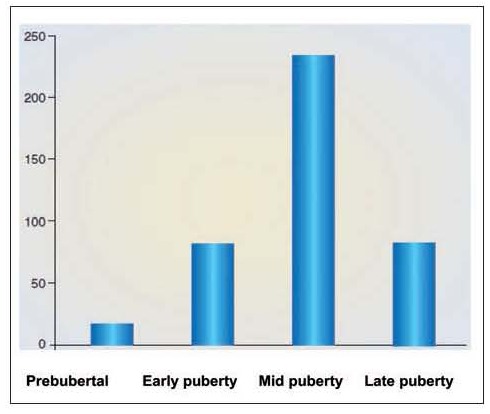

After the neonatal period, the adolescent age represents a peak incidence of gynecomastia. The reported prevalence in the literature varies widely, due to different methods of assessment and the assessments of different ages and groups of individuals. The incidence differs in many reports and ranges between 4 to 69% of palpable breast tissue. It may present as early as age 10, with a peak onset between the ages of 13 and 14 years (Figure 1). The typical onset occurs at 13 to 14 years of age, or Tanner stage 3 or 4 (Figure 2). This is followed by a decline of incidence in late teenage years. Only 10% of boys at the age of 17 years have persistent gynecomastia (3-7).

Figure 1.

Age distribution of 425 cases of gynecomastia observed in a single pediatric and adolescent endocrine clinic in Ferrara (De Sanctis V, personal observations)

Figure 2.

Distribution of 425 cases of gynecomastia in relation to pubertal status observed in a single pediatric and adolescent endocrine clinic in Ferrara (De Sanctis V, personal observations). The vertical line corresponds to the number of observed cases

Etiologies and pathogenesis

Most cases of adolescent gynecomastia (physiologic gynecomastia) have no known cause. An imbalance in the ratio of estrogen to androgens tissue levels is postulated as a major cause in the development of gynecomastia. In general, this imbalance between estrogen and androgen action occurs if there is an absolute increase in free estrogens, a decrease in endogenous production of free androgens, an increase in the free estrogen-to-free androgen ratio, androgen insensitivity, or an estrogen-like effect of drugs.

In adolescents with gynecomastia, endocrine investigations may include the measurement of serum concentrations of testosterone, estradiol, gonadotrophin, prolactin and thyroid function tests. Moore et al. (8) studied plasma profiles of 8 hormones over the course of prepuberty and puberty in adolescent males who developed gynecomastia and who did not. Throughout puberty, ratios of delta 4-androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate to estrone (E1) and estradiol (E2) were significantly lower in the gynecomastia group than in the control group. In contrast, ratios of plasma testosterone to E1 and E2 as well as plasma progesterone and prolactin (PRL) concentrations, were similar in both groups. Because of the adrenal origin of dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate, and of peripheral conversion of adrenal androgens to E1 and to E2, it is suggested that either decreased adrenal production of androgens and/or increased conversion of dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate and delta 4-androstenedione to estrogens cause transient gynecomastia in adolescent boys. Therefore, it appears to be a local imbalance between estrogen stimulation and the inhibitory action of androgens on breast tissue proliferation, although the majority of adolescents with gynecomastia have normal estrogen levels (9-15). This may be due to enhanced sensitivity of the breast tissue to normal circulating levels of estrogen even in the presence of normal circulating androgen concentrations. An increased aromatization of androgens to estrogens in the breast tissue itself as increased aromatase activity has been found in pubic skin fibroblasts of patients with gynecomastia (16).

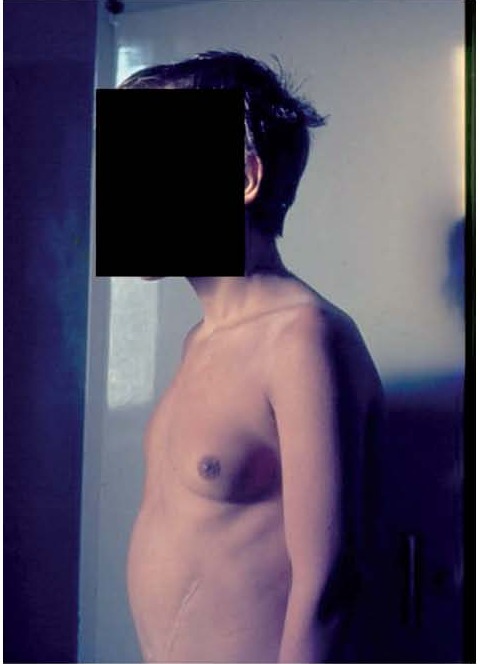

Secondary causes of gynecomastia in adolescents are relatively rare (less than 5%) and may arise from a broad array of uncommon pathological conditions (17-19). These are well described elsewhere and may include conditions such as: congenital anorchia, Klinefelter’s syndrome, testicular feminization, hermaphroditism, adrenal carcinoma, chronic liver disease, primary hypogonadism, secondary hypogonadism (Figure 3), testicular tumors, hyperthyroidism, renal disease and malnutrition (5,17-19). On the other hand, several drugs may induce proliferation of male breast tissue (20).

Figure 3.

Gynecomastia in an adolescent with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and chronic liver disease (De Sanctis V, personal observation)

Clinical assessment and diagnostic procedures are usually successful to differentiate these conditions from the common physiologic gynecomastia (17-19).

Does obesity play a role in the adolescent gynecomastia?

The prevalence of gynecomastia appears to be greater in obese adolescents. A study screened the database for young male “breast” specimens between 1997-2008. Sixty-nine patients were identified. By body mass index criteria (BMI), 51% were obese, 16% overweight and 33% normal-weighted (9).

In some studies, BMI is positively correlated with both breast diameter and the presence of gynecomastia in both adolescents and adults. Breast adipose tissue contains the aromatase enzyme complex that converts testosterone and androstenedione to E2 and E1, respectively. Peripheral androgen aromatization is enhanced with increased body mass index. Obese males show significantly increased plasma estradiol concentrations and low testosterone concentrations. Testosterone levels also improve on weight loss, which is the intervention of choice for obese men with or without low testosterone levels. In three small studies, letrozole or testolactone has been administered to morbidly obese men to improve their testosterone levels (21-23). Treatment resulted in normalization of testosterone levels in all subjects, with a concomitant suppression of the originally increased levels of estradiol. In addition, the increase in breast fat with weight gain may lead to pseudogynecomastia, which may or may not be associated with true gynecomastia (17-26).

Classification and grades of severity of gynecomastia

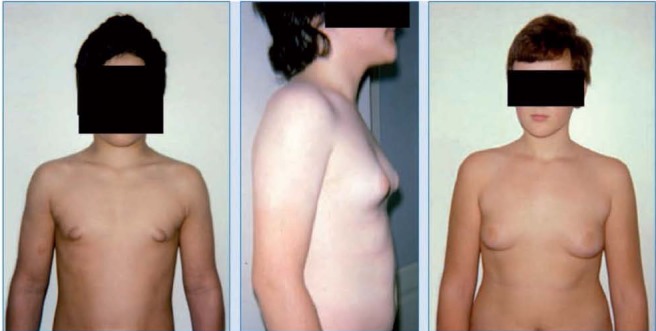

Simon et al. (9) identified four grades of gynecomastia:

Grade I: Small enlargement without skin excess

Grade IIa: Moderate enlargement without skin excess

Grade IIb: Moderate enlargement with minor skin excess

Grade III: Marked enlargement with excess skin, mimicking female breast ptosis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Different grades of gynecomastia according to Simon et al. classification (De Sanctis V, personal observations)

Rohrich et al. (10) have proposed a similar classification of gynecomastia with four grades of severity:

Grade I: Minimal hypertrophy (<250 g) without ptosis

Grade II: Moderate hypertrophy (250-500 g) without ptosis

Grade III: Severe hypertrophy (>500 g) with grade I ptosis

Grade IV: Severe hypertrophy with grade II or grade III ptosis

Bannayan et al. (27) have described three histological types of gynecomastia: florid, fibrous, and intermediate. The florid type is characterized by ductal hyperplasia and proliferation, with loose and edematous stroma. The fibrous type contains more stromal fibrosis and fewer ducts. The intermediate type of gynecomastia presents features of the two. In the majority of cases, if the duration of gynecomastia is greater than one year, the fibrous type is more prevalent and irreversible, which may limit success of medical treatments.

The course of the disease in relation to pubertal progression and severity

Pubertal gynecomastia is self-limited in 75 to 90% of adolescents and regresses over 1 to 3 years. Observation and reassurance are widely regarded as the safest and most reasonable treatment in mild cases. However, because gynecomastia in adolescents occurs at a delicate time when boys are increasingly conscious about self-image, the role of pharmacological or surgical therapies is always in question.

Zosi et al. (28) evaluated the progression with time in children with pubertal gynecomastia for a mean period of five years. Children were divided into 3 groups. Group A comprised 15 children with breast enlargement of less than 6 cm (mild gynecomastia), group B: 5 children with 6-11 cm (moderate) and group C: 5 children with breast tissue of more than 11cm (severe). This study denoted that mild gynecomastia regresses entirely in all patients, while moderate in only 20% after a 3 year duration while severe gynecomastia usually persists and requires management in 40% of cases. Pain is more common in patients with gynecomastia that is rapidly progressive or of recent onset.

In our experience, a regression of gynecomastia was observed, after a mean period of 3 years, in 84%, 47% and 20% of 220 adolescents with mild, moderate or severe gynecomastia (De Sanctis V, personal observations - unpublished data).

Investigating and managing cases of adolescent gynecomastia

The suggested diagnostic approach and treatment strategies for gynecomastia consist of expert opinion, case series, and observational studies. Therefore, the evidence is considered to be of low to very low quality. By acknowledging this low quality of evidence when discussing testing and treatment options with patients, physicians allow room in the process of decision making for consideration of other factors, such as resources, availability of services, and patients’ values and preferences (29).

For managing adolescent gynecomastia, a tailored therapy is advised.

Attentive waiting with biannual follow-up is appropriate for those with physiologic gynecomastia who are untroubled by symptoms and who have no features that suggest underlying disease. Few patients with adolescent gynecomastia need treatment for cosmesis or analgesia.

Early treatment can maximize benefit in adolescents with significant physical symptoms or emotional distress. Medical treatment appears to be more effective if used early in the course of the disease possibly after symptoms are first noted, whereas surgery can be performed at any time with similar results (30, 31).

For patients with non-physiologic gynecomastia, treatment is directed toward improving the underlying illness or discontinuing use of the contributing.

Mammography appears unnecessary in most men particularly in young male patients and should not be used as a routine imaging procedure.

Pharmacological treatment

Medical treatment of gynecomastia aims to correct the estrogen-androgen imbalance by three possible pathways: (a) blocking the effects of estrogens on the breast (e.g., clomiphene, tamoxifen, raloxifene); (b) administering androgens (e.g., danazol), and (c) inhibiting estrogen production (e.g., anastrozole, testolactone) (32-49).

Data on efficacy of pharmacological treatment of gynecomastia in adolescents is mostly limited to small case series and case reports without control groups, which makes conclusions difficult to draw. A number of medications have been used to treat gynecomastia.

Tamoxifen is an antiestrogen. Its principal mechanism of action is mediated by its binding to the estrogen receptor and the blocking of the proliferative actions of estrogen on mammary epithelium. It is thought to be an effective and safe treatment for physiologic, persistent pubertal or idiopathic gynecomastia.

A systematic review to assess the efficacy of tamoxifen in the management of idiopathic pubertal gynecomastia was performed by Lapid et al. (33) fifty nine studies were selected. There were no randomized controlled studies. The studies found have methodological flaws but show promising results.

No clinical side-effects were reported or observed. They concluded that tamoxifen may be effective for the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia and it seems safe to use and randomized controlled studies are necessary to confirm this indication.

A retrospective chart review of men presenting to a breast clinic for gynecomastia found that only 13 of 220 patients required medication for treatment. Patients were treated with 10 mg of tamoxifen per day for three months, and 10 of the 13 had resolution of pain and breast enlargement (34). A randomized controlled trial of 80 participants also found that 20 mg of tamoxifen once per week is as effective as 20 mg once per day (35).

Derman et al. (36) evaluated the efficacy of the tamoxifen treatment in 37 patients with pubertal gynecomastia with a diameter of over three cm. Pain and size reduction was seen in all patients with tamoxifen treatment. No long-term side effects of tamoxifen were observed. The dose of tamoxifen was increased in three patients due to poor response. Two of the treatment group had recurrence problem at follow-up. No patient required breast surgery.

Devoto et al. (37) studied 43 patients with gynecomastia, aged 12 to 62 years. Twenty seven patients had a pubertal physiological gynecomastia. Twenty patients had mastodynia and in 33, gynecomastia had a diameter over 4 cm. All were treated with tamoxifen 20 mg/day for 6 months. Mastodynia disappeared in all patients at three months. At six months gynecomastia disappeared in 26 patients (62%), but relapsed in 27%. Fifty two percent of gynecomastias over 4 cm and 90% of those of less than 4 cm in diameter disappeared (p<0.05). Fifty six percent of gynecomastias lasting more than two years and 70% of those of a shorter duration disappeared (p=NS). They concluded that tamoxifen is safe and effective for the treatment of gynecomastia and larger lesions have a lower response to treatment.

Another two small double-blind, crossover trials found only modest benefit when compared with placebo (38,39).

Histologically, the therapeutic effect of tamoxifen appears to be satisfactory.

In three cases who reported dissatisfaction with the results of tamoxifen treatment and were therefore submitted to adenectomy preceded by liposuction. Pathology results showed adipose tissue alone, with no evidence of intraductal epithelial proliferation. The lack of residual glandular breast tissue after treatment with tamoxifen proves that it is effective in histopathologically eliminating pubertal gynecomastia (40).

The long-term safety of tamoxifen was evaluated in 10 pubertal boys treated with tamoxifen for gynecomastia for more than 3 months. They were evaluated after 2.5-7 years (mean 4.6 years) to determine the side effects of this therapy. Authors did not find any serious side effects of tamoxifen in these patients (41).

Raloxifene is a second-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM). In 34 healthy males at the dose of 60 mg/day for one month it increased serum testosterone by 20%, and slightly decreased serum estradiol. When used in eugonadal patients with gynecomastia, 75% had a reduction in the size of breast tissue of at least 50% (average, 73%) in the first two months of treatment. However, the study was small and the males have wide range of ages (42).

In thirty eight patients with persistent pubertal gynecomastia who received reassurance alone or a 3- to 9-month course of an estrogen receptor modifier (tamoxifen or raloxifene) there was a mean reduction in breast nodule diameter by 2.1 cm after treatment with tamoxifen and 2.5 cm with raloxifene. Some improvement was seen in 86% of patients receiving tamoxifen and in 91% receiving raloxifene, but a greater proportion had a significant decrease (>50%) with raloxifene (86%) than tamoxifen (41%). No side effects were seen in any patients. Authors suggested that raloxifene may be safe and effective in reducing persistent pubertal gynecomastia, with a better response compared to tamoxifen (43).

Anastrozole, an aromatase enzyme, was used in a controlled trial of 80 patients with gynecomastia. However, the study demonstrated no statistically significant difference between anastrozole and placebo in the percentage of patients with greater than 50 percent breast volume reduction at three months (44).

Danazol is a synthetic steroid with antigonadotropic and anti-estrogenic activities that acts as an anterior pituitary suppressant by inhibiting the pituitary output of gonadotropins. It possesses some androgenic properties. Buckle et al. (45) treated 42 patients with gynaecomastia with danazol. There were 31 adults and 11 cases of pubertal gynaecomastia. Dosage schedules in adults were 300-600 mg a day and in adolescents 200-300 mg a day. In the 31 adults, marked regression of gynecomastia occurred in 18 and a moderate regression in 10, whilst in the 11 cases of puberty gynecomastia, there was a marked regression in 7 and a moderate regression in three patients. Plasma testosterone, FSH, and LH concentration fell in most patients.

Beck et al. (46) evaluated the effect of danazol treatment in pubertal boys with marked gynecomastia (breast size more than 6 cm in diameter). During danazol treatment (200 mg daily for 6 months) gonadotropin levels in response to luteinizing-hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) stimulation were blunted and testosterone values decreased. After 6 months of therapy, four of 5 boys treated so far, demonstrated a reduction of gynecomastia to a maximum of 3 cm in diameter. There were no signs of a recurrence of the marked pubertal gynecomastia in all boys after stopping danazol. These results indicate that danazol is a specific gonadotropin inhibitor acting at the hypothalamo-pituitary level. No side effects on other hormones or on the development of secondary sex characteristics were noted during and after danazol treatment.

Ting et al. (47) compared the efficacy of tamoxifen versus danazol in the treatment of 68 patients with idiopathic gynecomastia at different ages (range: 13-82 years). Medical treatment with either tamoxifen (20 mg/d) or danazol (400 mg/d) was offered and continued until a static response was achieved. Twenty-three patients were treated with tamoxifen and 20 with danazol. Complete resolution of the gynecomastia was recorded in 18 patients (78.2%) treated with tamoxifen, whereas only 8 patients (40%) in the danazol group had complete resolution. Five patients, all from the tamoxifen group, developed recurrence of breast mass. It was concluded that although the effect is more marked for tamoxifen compared with danazol, the relapse rate is higher for tamoxifen.

Plourde et al. (48) studied the effect of clomiphene citrate in 12 boys, aged 12 to 19 years, with persistent gynecomastia, at a dose of 50 mg/day by mouth for one to three months. The mean breast size decreased by 0% to 36%, with only five boys experiencing a reduction of greater than 20%. Five boys subsequently required reduction mammoplasty. Levels of urinary gonadotropins, serum testosterone, and estradiol increased significantly during therapy. The antiestrogen effects were achieved primarily at the level of breast tissue because the ratio of testosterone to estradiol remained unchanged during treatment. Authors concluded that clomiphene citrate in a dose of 50 mg/day resulted in only small decreases in persistent pubertal gynecomastia and was not a satisfactory medical therapy for the condition.

Testolactone is a non-selective, irreversible, steroidal aromatase inhibitor, thereby preventing the formation of estrogen from adrenal androstenedione and reducing endogenous estrogen levels.

Zachmann et al. (49) treated 22 boys with pubertal gynaecomastia (age 15.9±1.9 years) with testolactone (450 mg daily by mouth) for 2 to 6 months without side-effects. The mean breast gland diameter regressed from 4.4 to 3.3, 3.2 cm and 1.7 cm at 2, 4, and 6 months respectively, while pubic hair and testicular volume progressed normally. It was concluded that testolactone, an inhibitor of steroid aromatization, is an effective and safe medical treatment for pubertal gynaecomastia.

In conclusion, it appears that pharmacological therapy of persistent adolescent gynecomastia is reasonable effective if given early in the course of the disease and more successful in cases with small or moderate breast enlargement. In cases with marked enlargement with excess skin, mimicking female breast, surgery may be considered if no regression is observed after a period of observation of at least one year.

Surgical treatment

Surgical management of pubertal gynecomastia may be considered in non-obese male adolescents who present persistent breast enlargement after a period of observation of at least 12 months, breast pain or tenderness, and/or significant psychosocial distress. Obesity is not a contraindication to surgical approach. Liposuction techniques are helpful in those patients with considerable fat deposition in the breast during the removal of the glandular component. The aim of surgical treatment is to achieve a normal appearance of the masculine thorax with the smallest possible scar. Surgical treatment of gynecomastia requires an individualized approach.

The most commonly used technique is subcutaneous mastectomy that involves the direct resection of the glandular tissue using a periareolar or transareolar approach with or without associated liposuction. Skin resection is needed for more advanced cases (50, 51).

In grade I, the enlargement is caused solely by glandular proliferation without adipose accumulation. Surgical correction involves mammary adenectomy performed by a semicircular inferior periareolar incision. Liposuction is not required. Grade II is characterized by excessive glandular tissue and local adiposity. In these cases, liposuction and surgical excision must be combined in the same operation. Mammary adenectomy without liposuction leads to unsatisfactory outcomes, with an uneven surface or asymmetry. In grade III, the operation begins with liposuction and is followed by glandular excision with periareolar removal of the tissue. It is necessary to detach the excess skin to obtain a good chest silhouette. The hallmarks of grade IV are severe ptosis and a large amount of redundant skin. One of the techniques for reduction mastoplasty is used to remove gland and skin and flatten the chest outline (30).

The most frequent early complication following surgical management of gynecomastia is hematoma. Seroma, overresection with saucer-type deformity, underresection, unappealing scarring and infections are also observed. Patients and their parents or guardians should be well informed about possible risks, as some complications are managed surgically.

Figure 5.

Right areola-nipple necrosis following surgical management of gynecomastia. Tattoo was placed to achieve a “normal” areolar shape (De Sanctis V, personal observation)

Ultrasound-assisted liposuction (UAL) is another modified method that may facilitate the removal of tougher sub-areola glandular tissue at the time of liposuction. Care is needed with this technique to avoid the potential complication of thermal injury to the overlying skin. Standard liposuction or UAL in combination with gland resection through a minimal caudal semicircular periareolar incision and conventional liposuction effectively corrects most grades of gynecomastia (52).

An alternative modification to the simple liposuction is the power-assisted liposuction technique. This is performed to contour the breast tissue without having to exert as much physical force as standard liposuction with a syringe and cannula. The cannula reciprocates at a controlled but surgeon adjustable rate, with separate precise control of the suction pressure. This technique works very effectively in combination with a tumescent and super tumescent approach.

The aspirate volume from liposuction can range from 50 to over 1,000 mL. In contrast the excision of the fibroglandular tissue can range from a few grams to over 1,000 g. This illustrates the different degrees of gynecomastia for which surgery is used (53-55).

The use of mammotome is a minimal invasive tool that appears safe and ensures reasonable cosmesis and patient satisfaction rates, although there are only limited reports of its use in gynecomastia and no long-term follow-up data (56). The potential risk of skin injury and hemorrhage may limit the use of mammotome.

In general, surgical treatment produces good cosmesis and is well tolerated. Nevertheless invasive techniques that require minimal surgical incision have recently emerged and may offer faster recovery and lower rates of local complications. Histologic analysis is recommended in true gynecomastia corrections to rule out unexpected histologic findings.

In conclusion, adolescent gynecomastia has a favorable prognosis with spontaneous complete or partial resolution. Small percent have persistent gynecomastia after the end of pubertal development and some adolescents have concerns about the cosmetic correction. Therefore, the decision to perform surgery depends on the degree to which this condition has affected the quality of life and on their desire for cosmetic correction (57-59).

References

- 1.Nuttall FQ. Gynecomastia as a physical finding in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;48:338–340. doi: 10.1210/jcem-48-2-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nydick M, Bustos J, Dale JH Jr, Rawson RW. Gynecomastia in adolescent boys. JAMA. 1961;178:449–454. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040440001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma NS, Geffner ME. Gynecomastia in prepubertal and pubertal men. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:465–470. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328305e415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bembo SA, Carlson HE. Gynecomastia: its features, and when and how to treat it. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71:511–517. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.71.6.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:490–495. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302183280708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgiadis E, Papandreou L, Evangelopoulou C, Aliferis C, Lymberis C, Panitsa C, Batrinos M. Incidence of gynaecomastia in 954 young males and its relationship to somatometric parameters. Ann Hum Biol. 1994;21:579–587. doi: 10.1080/03014469400003582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Hanlon DM, Kent P, Kerin MJ, Given HF. Unilateral breast masses in men over 40: a diagnostic dilemma. Am J Surg. 1995;170:24–26. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore DC, Schlaepfer LV, Paunier L, Sizonenko PC. Hormonal changes during puberty: V. Transient pubertal gynecomastia: abnormal androgen-estrogen ratios. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;58:492–499. doi: 10.1210/jcem-58-3-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon BE, Hoffman S, Kahn S. Classification and surgical correction of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;51:48–52. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohrich RJ, Ha RY, Kenkel JM, Adams WP Jr. Classification and management of gynecomastia: defining the role of ultrasound-assisted liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:909–923. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000042146.40379.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma NS, Geffner ME. Gynecomastia in prepubertal and pubertal men. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:465–470. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328305e415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abaci A, Buyukgebiz A. Gynecomastia: review. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2007;5:489–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee PA. The relationship of concentrations of serum hormones to pubertal gynecomastia. J Pediatr. 1975;86:212–215. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaFranchi SH, Parlow AF, Lippe BM, Coyotupa J, Kaplan SA. Pubertal gynecomastia and transient elevation of serum estradiol level. Am J Dis Child. 1975;129:927–931. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1975.02120450035007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bidlingmaier F, Knorr D. Plasma testosterone and estrogens in pubertal gynecomastia. Z Kinderheilkd. 1973;115:89–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00438995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bulard J, Mowszowicz I, Schaison G. Increased aromatase activity in pubic skin fibroblasts from patients with isolated gynecomastia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:618–623. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-3-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass AR. Gynecomastia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23:825–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biro FM, Lucky AW, Huster GA, Morrison JA. Hormonal studies and physical maturation in adolescent gynecomastia. J Pediatr. 1990;116:450–455. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82843-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen H, Webb ML, DiVasta AD, Greene AK, Weldon CB, Kozakewich H, Perez-Atayde AR, Labow BI. Adolescent gynecomastia: not only an obesity issue. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:688–690. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181dba827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sansone A, Romanelli F, Sansone M, Lenzi A, Di Luigi L. Gynecomastia and hormones. Endocrine. 2017;55:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-0975-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Ronde W, de Jong FH. Aromatase inhibitors in men: effects and therapeutic options. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011 Jun 21;9:93. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-93. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zumoff B, Miller LK, Strain GW. Reversal of the hypogonadotropic hypogonadism of obese men by administration of the aromatase inhibitor testolactone. Metabolism. 2003;52:1126–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(03)00186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loves S, Ruinemans-Koerts J, de Boer H. Letrozole once a week normalizes serum testosterone in obesity-related male hypogonadism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:741–747. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al Qassabi SS, Al-Harthi SM, Al-Osali ME. Mixed gynecomastia. Saudi Med J. 2015;36:1115–1117. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.9.11778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venkata Ratnam B. How important is “pseudogynecomastia”? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35:668–669. doi: 10.1007/s00266-010-9629-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yazici M, Sahin M, Bolu E, Gok DE, Taslipinar A, Tapan S, Torun D, Uckaya G, Kutlu M. Evaluation of breast enlargement in young males and factors associated with gynecomastia and pseudogynecomastia. Ir J Med Sci. 2010;179:575–583. doi: 10.1007/s11845-009-0345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bannayan GA, Hajdu SI. Gynecomastia: clinicopathologic study of 351 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1972;57:431–437. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/57.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zosi P, Karakaidos D, Triantafyllidis G, Milioni N, Franglinos P, Karis C. Natural course of pubertal gynecomastia. Endocrine Absstact. 2002;4:P18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swiglo BA, Murad MH, Schünemann HJ, Kunz R, Vigersky RA, Guyatt GH, Montori VM. A case for clarity, consistency, and helpfulness: state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines in endocrinology using the grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:666–673. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barros AC, Sampaio Mde C. Gynecomastia: physiopathology, evaluation and treatment. Sao Paulo Med J. 2012;130:187–197. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802012000300009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson RE, Murad MH. Gynecomastia: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:1010–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60671-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordt CA, Di Vasta AD. Gynecomastia in adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:375–382. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328306a07c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lapid O, van Wingerden JJ, Perlemuter L. Tamoxifen therapy for the management of pubertal gynecomastia: a systematic review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2013;26:803–807. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2013-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanavadi S, Baneq’ee D, Monypenny IJ, Mansel RE. The role of tamoxifen in the management of gynaecomastia. Breast. 2006;15:276–280. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bedognetti D, Rubagotti A, Conti G, Francesca F, De Cobelli O, Canclini L, Gallucci M, Aragona F, Di Tonno P, Cortellini P, Martorana G, Lapini A, Boccardo F. An open, randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial comparing the efficacy of two tamoxifen schedules in preventing gynaecomastia induced by bicalutamide monotherapy in prostate cancer patients. Eur Urol. 2010;57:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derman O, Kanbur NO, Kutluk T. Tamoxifen treatment for pubertal gynecomastia. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2003;15:359–363. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2003.15.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devoto CE, Madariaga AM, Lioi CX, Mardones N. Influence of size and duration of gynecomastia on its response to treatment with tamoxifen. Rev Med Chil. 2007;135:1558–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker LN, Gray DR, Lai MK, Levin ER. Treatment of gynecomastia with tamoxifen: a double-blind crossover study. Metabolism. 1986;35:705–708. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDermott MT, Hofeldt FD, Kidd GS. Tamoxifen therapy for painful idiopathic gynecomastia. South Med J. 1990;83:1283–1285. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199011000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akgül S, Kanbur N, Güçer S, Safak T, Derman O. The histopathological effects of tamoxifen in the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25:753–755. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2012-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Derman O, Kanbur N, Kilic I, Kutluk T. Long-term follow-up of tamoxifen treatment in adolescents with gynecomastia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2008;21:449–454. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2008.21.5.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan HN, Blamey RW. Endocrine treatment of physiological gynaecomastia. BMJ. 2003;327:301–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7410.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawrence SE, Faught KA, Vethamuthu J, Lawson ML. Beneficial effects of raloxifene and tamoxifen in the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia. J Pediatr. 2004;145:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plourde PV, Reiter EO, Jou HC, Desrochers PE, Rubin SD, Bercu BB, Diamond FB Jr, Backeljauw PF. Safety and efficacy of anastrozole for the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4428–4433. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckle R. Danazol therapy in gynaecomastia; recent experience and indications for therapy. Postgrad Med J. 1979;55(Suppl 5):71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beck W, Stubbe P. Endocrinological studies of the hypothalamo-pituitary gonadal axis during danazol treatment in pubertal boys with marked gynecomastia. Horm Metab Res. 1982;14:653–657. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1019110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ting AC, Chow LW, Leung YF. Comparison of tamoxifen with danazol in the management of idiopathic gynecomastia. Am Surg. 2000;66:38–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plourde PV, Kulin HE, Santner SJ. Clomiphene in the treatment of adolescent gynecomastia. Clinical and endocrine studies. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137:1080–1082. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1983.02140370040013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zachmann M, Eiholzer U, Muritano M, Werder EA, Manella B. Treatment of pubertal gynaecomastia with testolactone. Acta Endocrinol Suppl (Copenh) 1986;279:218–226. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.112s218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Webster MH. Plastic surgery of the breast. Practitioner. 1980;224:406–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Webster DJ. The male breast. Br J Clin Pract. 1989;68:137–142. discussion 157-158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang WT, Whitman GJ, Yuen EH, Tse GM, Stelling CB. Sonographic features of primary breast cancer in men. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:413–416. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lista F, Ahmad J. Power-assisted liposuction and the pull through technique for the treatment of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:740–747. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000299907.04502.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramon Y, Fodor L, Peled IJ, Eldor L, Egozi D, Ullmann Y. Multimodality gynecomastia repair by cross-chest power-assisted superficial liposuction combined with endoscopic-assisted pullthrough excision. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:591–594. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000189664.88464.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hammond DC, Arnold JF, Simon AM, Capraro PA. Combined use of ultrasonic liposuction with the pull-through technique for the treatment of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:891–895. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000072254.75067.F7. discussion 896-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iwuagwu OC, Calvey TA, Ilsley D, Drew PJ. Ultrasound guided minimally invasive breast surgery (UMIBS): a superior technique for gynecomastia. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52:131–133. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000095441.40759.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Courtiss EH. Gynecomastia: analysis of 159 patients and current recommendations for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:740–753. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prado AC, Castillo PF. Minimal surgical access to treat gynecomastia with the use of a power-assisted arthroscopicendoscopic cartilage shaver. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:939–942. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000153237.35202.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu J, Huang J. Surgical management of gynecomastia under endoscope. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Techniq A. 2008;18:433–437. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]