Abstract

Background and aim of the study:

Physical performance is the result of a complex combination of several factors such as genetic and anthropometric aspects, nutrition and hormonal status. In the past few years many studies have considered the impact of vitamin D on muscular strength and athletic performance. The aim of the present study was to assess the anthropometric measures impacting on physical performance in a group of professional rugby athletes. As a secondary aim we investigated a possible relationship between baseline vitamin D status and athletic performance status in these subjects.

Methods:

All rugby players completed a test–retest reliability study on performance measures, as 70kg jump squat and body weight (BW) jump squat to assess musculoskeletal performance. Additionally at the time point we collected a blood sample of every athletes for the assessment of serum vitamin D.

Results:

We found that lean mass was an important independent predictor of performance score in 70kg jump squat (p=0.007, R2=0.74) and BW jump squat (p=0.010, R2=0.66) in these well trained athletes. No statistically significant association was present between performance score and serum vitamin D in this specific setting.

Conclusions:

We demonstrate a positive interaction between lower limb lean mass and performance score, but we have not been able to identify any statistically significant association between worsening in performance measures and decrease of serum 25 OH Vitamin D. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: athletic performance, rugby, lean mass, vitamin D

Blackground

Rugby is a high-intensity sport, intermittent in nature, that combines a variety of physical abilities including aerobic power, speed, agility and muscular strength (1-4) Traditionally, especially in top level professional rugby players, forwards and backs require different physical attributes, although being both involved in contacts and tackles. Specifically, forwards are involved in scrumming so that high level of strength is required and tend to have a higher body mass (2), because they are involved in scrumming, whereas backs perform a higher frequency of sprints per match compared to those required by forwards (5).

Physical performance is the result of the complex combination of several factors (6) including genetic components, anthropometric features, nutrition and physiological hormonal status that are likely to limit and contribute to effective athletic performance. In fact the literature is quite limited and outdated and reports different analyses of anthropometric characteristics as well as body composition in relation to physical tests (7-10).

Furthermore, because of the highly intermittent nature of rugby, it is difficult to define an optimal body composition that encompasses all elite players, because of the differences that exist within players and teams, in playing positions (11).

The assessment of body composition in professional rugby players is frequently performed as part of their routine monitoring procedures (12) in order to optimize competitive performance and to monitor the success of training regimens. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is an universally accepted method for the assessment of body composition in the athletic population since it allows the acquisition of regional and total body composition without the need for costly or not sensitive medical imaging techniques (13). It uses a 3-compartment model and currently is a validated, reliable, and safe technique that forward detail information regarding the levels of body mass (BM), fat mass (FM), lean mass (LM), bone mineral content (BMC) and bone mineral density (BMD) in different body segments (14).

Indeed, in the past two decades evidence has shown a correlation between vitamin D, a secosteroid hormone (15), and athletic performance (16-19). 25(OH)D exert an effect on muscle by modifying the expression of several genes involved in muscle protein synthesis affecting muscle strength and size, reaction time, balance, coordination, endurance, inflammation, and immunity, all impacting on athletic performance (16, 17).

Aim of the work

We conducted this study in well trained professional male rugby players who were active in the top division of Italian rugby during season 2012-13, living in Northern Italy. The aim of the present study was to assess the anthropometric measures impacting on physical performance in professional rugby athletes. In order to achieve this aim BM, FM, LM, and BMC were assessed by the gold standard evaluation method (DXA). As a secondary aim we investigated a possible relationship between baseline vitamin D status and athletic performance in these subjects.

Methods

Study subjects

The study was performed in April at the end of the 2012/2013 season in healthy professional male rugby players, playing in the Italian Major Rugby League (Eccellenza). Athletes trained for over 30 hours per week and at the time of blood drawing they were free from illness or injury, as determined by a pre-season medical examination and periodical clinical evaluation during the following months. All participants received a clear explanation of the study and provided written informed consent prior to participating in the study, and the protocol was approved by the local ethic committee.

None of the athletes was taking any medications potentially interfering with vitamin D metabolism such as glucocorticoids, barbiturates, anticonvulsants or any Vitamin D supplements, and none was a regular sunbed user. This allow to eliminate potentially confounding variables

Anthropometric parameters were measured (height, weight), and Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2).

All participants were regular first team players of the same rugby league club performing similar training regimes, with small individual variations in training program based on playing position and individual physical abilities.

Study design

In April all athletes had venous blood sample drawn at the time point for the assessment of total 25(OH)D. Additionally, all rugby players completed a test–retest reliability study on the various performance measures, as body weight (BW) jump squat and 70 kg jump squat to assess musculoskeletal performance.

Assessment of total 25(OH)D concentration

All athletes underwent a blood tests to evaluate the assessment of serum 25(OH)D as previously described (20). Blood samples were collected early in the morning in sterile tubes and delivered to the laboratory of the Parma University Hospitals where they were centrifuged and the serum was harvested and stored at a temperature of -30° for further evaluation. 25(OH) D concentrations were determined by chemiluminescence immunoassay CLIA (LIASON® 25 OH Vitamin D TOTAL Assay). The measurement of serum 25(OH)D is the most valid indicator of vitamin D status (normal values: > 30 ng/dl) (21).

Performance tests

Performance testing took place on the same day of blood collection to exclude a potential time-of-day effect. All athletes were familiar with the testing procedures as part of their regular strength training routine. Three measurements were completed for each test consecutively and the best score was recorded. During the execution of these tests, the players were verbally encouraged to give their maximal effort.

Body weight squat jump and 70 kg squat jump are an expression of lower limb explosive power. BW squat jump was performed following a standardized warm-up and without counter movement; the athlete takes a squat position with static phase of about 2, then moves on to a jump trying to use the full power of the lower limbs. 70 kg squat jump was performed in the same ways, but an overload was positioned on athletes’ shoulders. A microcomputer system for strength diagnostic and feedback monitoring of weight training was used (Tendo Unit, Slovack Republic).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were normally distributed and were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). To test the correlation between performance score and other clinical variables, Pearson correlation test was performed. Variables significantly correlated with performance in a univariate analysis were included as independent variables in a multiple linear regression analysis, to determine which accounted for performance score (dependent variable). Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS version 21.0) for Windows.

Results

The study population included twenty-one healthy professional male rugby players (age 25±4 years), twenty Caucasians and one of Hispanic heritage. Anthropometric, biochemical and performance variables are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects (n=21)

| Variable | Mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25±4 |

| Weight (kg) | 96±15 |

| Height (cm) | 182±5 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 28,9±3,7 |

| Fat mass (g)* | 18771±6579 |

| Lean mass (g)* | 75111±8769 |

| Fat mass (%)* | 18.9±3.9 |

| 25(OH)D (ng/ml) | 19.1±5.3 |

| 70 kg jump squat performance score | 3540±437 |

| BW jump performance score | 3269±442 |

data obtained from DXA Total Body analysis

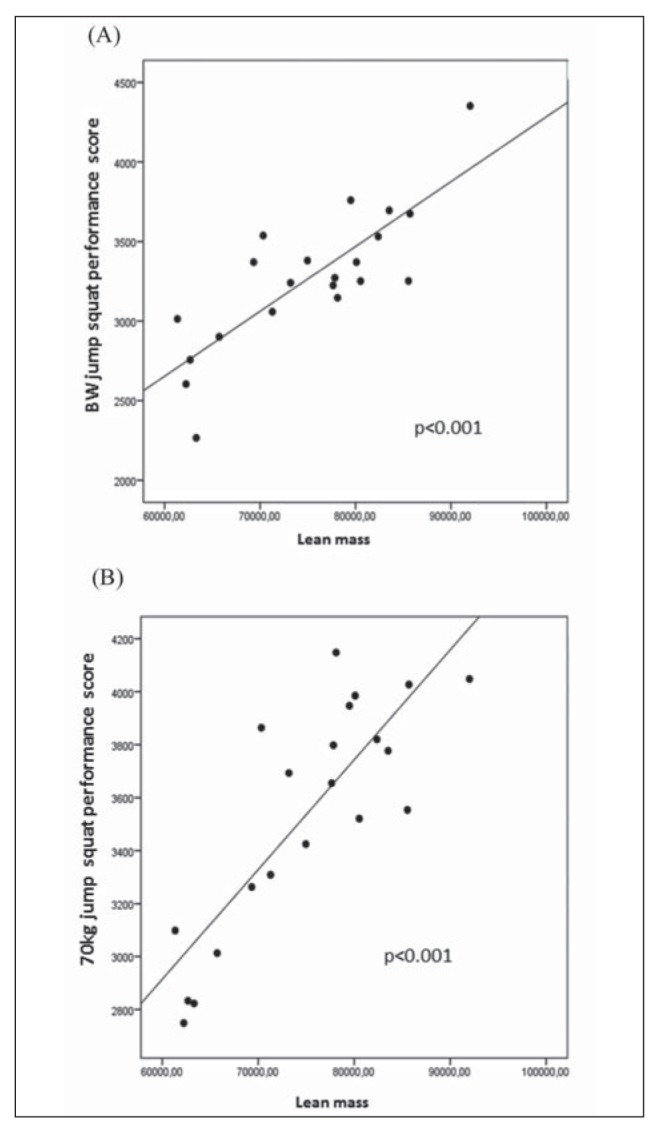

BW jump squat scores were significantly directly correlated with weight (r=0,78, p=<0.001), BMI (r=0,64, p=0,003), lean mass (r=0,81, p<0.001) and rugby players’ position (t=3,00, p=0.007) (Table 2; Fig. 1A).

Table 2.

Correlation (Univariate analysis) between performance scores (PS) and variables

| Variables | 70 kg jump squat PS | BW jump squat PS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson r | p value | Pearson r | p value | |

| Age (years) | 0.14 | n.s. | 0.08 | n.s. |

| Weight (kg) | 0.72 | <0.001 | 0.78 | <0,001 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 0.62 | 0.003 | 0.64 | 0.002 |

| Fat mass (%) | 0.37 | n.s. | 0.43 | n.s. |

| Lean mass (g) | 0.83 | <0.001 | 0.81 | <0.001 |

| 25(OH)Vit. D (ng/ml) | -0.11 | n.s. | -0.02 | n.s. |

| t Student | p value | t Student | p value | |

| Rugby players’ position Forward=0 Back=1 | 4.24 | <0.001 | 3.00 | 0.007 |

Figure 1.

Linear correlation between performance score and lean mass. (A) BW jump squat; (B) 70 kg jump squat

70kg jump squat scores were significantly directly correlated with weight (r=0,72, p<0.001), BMI (r =0,62, p Z 0,003), lean mass (r=0,83, p <0.001) and rugby players’ position (t=4,24, p<0.001) (Table 2; Fig. 1B).

A multiple linear regression analysis, after adjustment for age, BMI, total lean mass and rugby players’ position indicated total lean mass, as the only independent predictor of performance score in BW jump squat (p=0.010, R2=0.66) and 70 kg jump squat (p=0.007, R2=0.74). (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis between performance scores (PS) and variables

| Independent variable | 70 kg jump squat PS | BW jump squat PS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beta | t | p value | beta | t | P value | |

| Age (years) | 0.033 | 0.236 | 0.11 | -0.53 | -0.326 | 0.75 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | -0.221 | -0.931 | 0.36 | -0.91 | -0.336 | 0.74 |

| Lean mass (g) | 0.812 | 3.098 | 0.007 | 0.881 | 2.935 | 0.010 |

| Rugby players’ position Forward=0 Back=1 | -0.282 | -1.532 | 0.14 | -0.014 | -0.066 | 0.95 |

Discussion and conclusions

We investigated the physiological and anthropometric characteristics of rugby league players and their association with performance scores, like 70 kg jump squat and BW jump squat. First of all, in literature we could not find any study that used these performance scores in a similar population.

Our results suggest two important findings. We demonstrated a positive association between lower limb lean mass and performance score. This group of athletes is engaged in high-resistance strength training able to enhance physical performance and increase muscle-skeletal mass (22). Chronic exposure to this type of activity is known to induce marked increase in muscular strength, due to a set of neurological and morphological adaptations (23). This may suggest that modifications and improvements in lower body muscularity are required to obtain a well-developed physical performance and may facilitate greater repeated high-intensity effort work rates in rugby players (24, 25). Furthermore, the presence of this significant association after adjustment for age, BMI, total lean mass and playing role, supports this conclusion.

We failed to identify any statistically significant association between performance measures and serum 25(OH)D. Many observational studies, mainly in elderly populations, indicate that vitamin D status is positively associated with muscle strength and physical performance (26, 27). Clinically, vitamin D deficiency induces myopathy that is usually characterized by proximal muscle weakness or by nonspecific patterns, such as hypotonia, waddling gait, impaired physical function, uniform generalized muscle wasting, and bone pains (28, 29). It is possible that the benefits of an intensive training may outweigh the negative impacts of 25(OH)D deficiency, at least in the short term or in particular in this so highly training subjects, raising the hypothesis that the same level of vitamin D exert different effects according to the specific population considered. Further, given the myopathy associated with vitamin D deficiency typically presents as a proximal muscle weakness, we can’t exclude the existence of a different sensibility to vitamin D among several muscle group. Therefore, we may speculate that we are facing a false negative observation, because we evaluated only lower muscle group. Finally, a cross sectional study design with the relatively small sample size employed, may not be sensitive enough to formally evaluate this question.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that players’ performance in fitness training should be always monitored and improved in order to develop a winning team in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the rugby athletes who participate in this study.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding/support

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant by Abiogen Pharma, Pisa-Italy and by grant FIL 2012 to Giovanni Passeri and grant FIL 2013 to Giovanni Passeri both from University of Parma.

References

- 1.Gabbett TJ, King T, Jenkins D. Applied physiology of rugby league. Sports medicine. 2008;38:119–38. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker DG, Newton RU. Comparison of lower body strength, power, acceleration, speed, agility, and sprint momentum to describe and compare playing rank among professional rugby league players. Journal of strength and conditioning research. 2008;22:153–8. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31815f9519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meir R, Newton R, Curtis E, Fardell M, Butler B. Physical fitness qualities of professional rugby league football players: Determination of positional differences. Journal of strength and conditioning research. 2001;15:450–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor D. Physiological characteristics of professional rugby league players. Strength conditioning coach. 1996;4:21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appleby B, Newton RU, Cormie P. Changes in strength over a 2-year period in professional rugby union players. Journal of strength and conditioning research. 2012;26(9):2538–46. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823f8b86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tucker R, Collins M. What makes champions? A review of the relative contribution of genes and training to sporting success. British journal of sports medicine. 2012;46(8):555–61. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell W. Anthropometry of the young adult college rugby player in Wales. British journal of sports medicine. 1973;7:298–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell W. Body composition of rugby union football players. British journal of sports medicine. 1979;13:19–23. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.13.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maud PJ. Physiological and anthropometric parameters that describe a rugby union team. British journal of sports medicine. 1983;17:16–23. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.17.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid R, Williams C. A concept of fitness and its measurement in relation to rugby union football. British journal of sports medicine. 1974;8:96–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabbett TJ. Science of rugby league football: A review. Journal of sports sciences. 2005;23:961–76. doi: 10.1080/02640410400023381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harley JA, Hind K, O’hara JP. Three-compartment body composition changes in elite rugby league players during a super league season, measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Journal of strength and conditioning research. 2011;25(4):1024–29. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181cc21fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ackland TR, Lohman TG, Sundgot-Borgen J, Maughan RJ, Meyer NL, Stewart AD, Müller W. Current status of body composition assessment in sport: review and position statement on behalf of the ad hoc research working group on body composition health and performance, under the auspices of the I.O.C. Medical Commission. Sports Medicine. 2012;42:227–49. doi: 10.2165/11597140-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laskey MA. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and body composition. Nutrition. 1996;12:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0899-9007(95)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen CJ. Vitamin D deficiency. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364:248–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1009570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannell J, Hollis B, Sorenson M, et al. Athletic performance and Vitamin D. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2009;41(5):1102–10. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181930c2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceglia L. Vitamin D and its role in skeletal muscle. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2009;12(6):628–33. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328331c707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dirks-Naylor AJ, Lennon-Edwards S. The effects of vitamin D on skeletal muscle function and cellular signaling. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2011;125:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wacker M, Holick MF. Sunlight and Vitamin D: A global perspective for health. Dermatoendocrinology. 2013;5(1):51–108. doi: 10.4161/derm.24494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caroli B, Pasin F, Aloe R, Gnocchi C, Dei Cas A, Galli C, Passeri G. Characterization of skeletal parameters in a cohort of North Italian rugby players. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2014;37(7):609–17. doi: 10.1007/s40618-014-0070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binkley N, Krueger DC, Morgan S, Wiebe D. Current status of clinical 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurement: an assessment of between laboratory agreements. Clinical Chimica Acta. 2010;14:1976–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston RD, Gabbett TJ, Jenkins DG. Applied sport science of rugby league. Sports medicine. 2014;44(8) doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0190-x. 10871100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folland JP, Williams AG. The adaptations to strength training: morphological and neurological contributions to increased strength. Sports medicine. 2007;37(2):145–68. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabbett TJ. Physiological characteristics of junior and senior rugby league players. British journal of sports medicine. 2002;36(5):334–9. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.5.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Lacey J, Brughelli ME, McGuigan MR, Hansen KT. Strength, speed and power characteristics of elite rugby league players. Journal of strength and conditioning research. 2014;28(8):2372–5. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dietrich T, Orav EJ, Hu FB, Zhang Y, Karlson EW, et al. Higher 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with better lower-extremity function in both active and inactive persons aged > or ¼60 y. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2004;80:752–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visser M, Deeg DJ, Lips P. Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone levels as determinants of loss of muscle strength and muscle mass (sarcopenia): the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88:5766–72. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schott GD, Wills MR. Muscle weakness in osteomalacia. The Lancet. 1976;1(7960):626–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skaria J, Katiyar BC, Srivastava TP, Dube B. Myopathy and neuropathy associated with osteomalacia. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 1975;51:37–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1975.tb01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]