Abstract

Background:

Dyspnoea-12 is a valid and reliable scale to assess dyspneic symptom, considering its severity, physical and emotional components. However, it is not available in Italian version due to it was not yet translated and validated. For this reason, the aim of this study was to develop an Italian version Dyspnoea-12, providing a cultural and linguistic validation, supported by the quantitative and qualitative content validity.

Methods:

This was a methodological study, divided into two phases: phase one is related to the cultural and linguistic validation, phase two is related to test the quantitative and qualitative content validity. Linguistic validation followed a standardized translation process. Quantitative content validity was assessed computing content validity ratio (CVR) and index (I-CVIs and S-CVI) from expert panellists response. Qualitative content validity was assessed by the narrative analysis on the answers of three open-ended questions to the expert panellists, aimed to investigate the clarity and the pertinence of the Italian items.

Results:

The translation process found a good agreement in considering clear the items in both the six involved bilingual expert translators and among the ten voluntary involved patients. CVR, I-CVIs and S-CVI were satisfactory for all the translated items.

Conclusions:

This study has represented a pivotal step to use Dyspnoea-12 amongst Italian patients. Future researches are needed to deeply investigate the Italian version of Dyspnoea-12 construct validity and its reliability, and to describe how dyspnoea components (i.e. physical and emotional) impact the life of patients with cardiorespiratory diseases. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: breathlessness, dyspnea, scale, translation, validity

Introduction

Dyspnoea is a subjective symptomatic manifestation, typically defined as a complex and multidimensional experience (1, 2). It is commonly described as a distressing symptom, which is often associated with a wide range of physical and emotional consequences (e.g. pain perception, fatigue, depression and anxiety), affecting patients overall quality of life (QoL) (1-5). Hence, dyspnoea assessment is a key element of its management and identification of correct clinical pathways of patients with cardiorespiratory diseases (6, 7). Thus, dyspnoea is considered a cardinal symptom for its prognostic value (6), and even considering that its correct management has an impact on the disease treatment efficacy (8).

Dyspnoea is typically assessed using direct or indirect approaches. The most common direct assessments are represented by visual analogue scales or by the modified Borg index (9). However, such approaches are limited by the mono-dimensional nature of the measurements, which often use single-item scales that do not capture the complexity of this multidimensional symptom. Indirect approaches assess the level of physical activities that patients are not able to accomplish due to their dyspnoeic symptomatology (2) or capture the impact of dyspnoea to the patients QoL (10). Such scales provide useful information but they do not measure dyspnoea per se.

More recently, the development of the Dyspnoea-12, a brief self-report scale has addressed the abovementioned limitations to provide a measure of dyspnoea that incorporates its multidimensional components. Dyspnoea-12 was developed using dyspnoea descriptors identified in a comprehensive literature review of the language used by patients to describe the experience of breathlessness (2). The initial pool of 81 items was reduced to 12, using hierarchical methods and Rach analysis (2). Dyspnoea-12 has been validated for use in different clinical situations and across many cardiorespiratory conditions (2, 3, 11).

Dyspnoea-12 is currently available for English speaking populations (i.e. original version) (2) and in Arabic (11) and others not yet published (JY personal correspondence). Although many scales are available to assess dyspnoea in patients with different cardiorespiratory diseases (e.g. HF, COPD, cancer, asthma) (9, 14-17), Dyspnoea-12 has a number of advantages: (a) scale briefness (2); (b) clear reliability and psychometrics proprieties (i.e. construct validity) in COPD (2), asthma (12), interstitial lung disease (13), lung cancer (1), and pulmonary hypertension (3); (c) it is the unique single scale which measure not only the symptom severity, but also the physical and emotional symptom components (2, 3, 11, 12, 13).

The aim of the current study was to develop an Italian version Dyspnoea-12 and assess its content validity.

Methods

This was a methodological study, divided into two phases: phase one is related to the cultural and linguistic validation, phase two is related to test the quantitative and qualitative content validity.

Scale description

Dyspnoea-12 uses 12 items (i.e. symptom descriptors) to assess the overall severity of dyspnoea, also giving a quantification of its physical and psychological dimensions (i.e. scale domains). Each item is rated using a four-point Likert scale (from zero to three), and the dyspnoea severity is computed summing each item response. Thus, Dyspnoea-12 total score ranges from 0 to 36, where higher values indicate more severe dyspnoeic symptoms. The physical domain is computed summing the first seven items, while the psychological one (i.e. emotional domain) is computed summing the items 8-12 (2, 3, 12, 13).

Phase one: cultural and linguistic validation

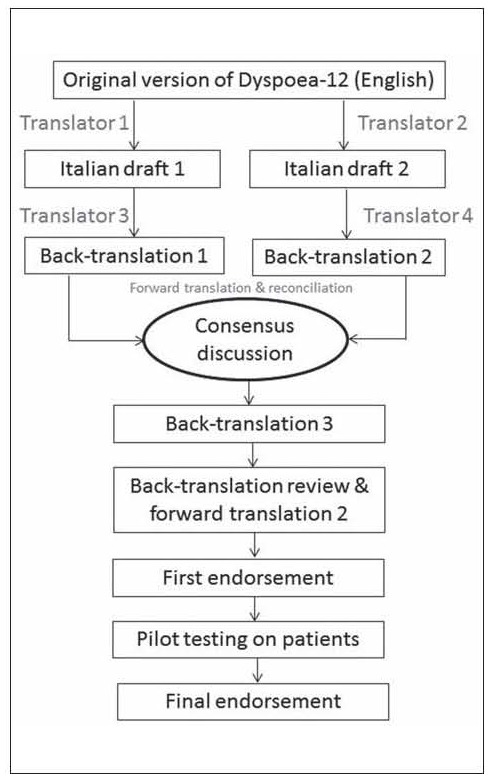

Importing Dysponea-12 for the Italian use has required a considerable effort by researchers to maintain the quality of translation, for this reason the methodology of this phase strictly followed an adaptation of the Brislin’s classic translation model (18), which was described by Jones et al. (19). According to Jones et al. (2001), this phase was performed with a combined translation technique which uses a group approach when applying the back-translation method and bilingual technique. The setting of phase one was a teaching hospital of northern Italy, and this phase was performed from August to October 2016. The translation process is schematically described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic flow chart of the standardized translation process of the Dyspnoea-12

At the beginning of the process, a project manager (RC) was identified by the research team to control the rigor of the overall translation. Then, two bilingual experts (one physician and one nurse) have prepared two translated versions of Dyspoea-12 from English to Italian. Each Italian version was blindly back translated to the English by two other bilingual experts (one physician and one psychologist). The four bilingual experts had a consensus group discussion, involving other two bilingual members (another nurse and one patient), and aimed to ensure the best cultural equivalence, using the most comprehensible Italian wording for each translated item, identifying the possible differences between the Italian and English versions. At the end of the consensus discussion, the project manager has assessed the degree of consensus by the use of an inter-rater agreement index (i.e. Fleiss’ Kappa), asking to the experts to rate each Italian-translated item with a Likert scale from one to five (1=completely not agree; 5=completely agree). The consensus was considered good when the agreement among raters was higher than 0,80.

Then, Italian Dyspnoea-12 version was backtranslated into English again by an independent native English speaker translator (nurse), but even speaking a certified fluent Italian language. The back-translation is reviewed against the English version of the Dyspnoea-12 by the project manager (i.e. back translation review). The project manager has passed the back translation review report to the correspondence author of the original scale to receive any suggestions or possible issues, which should be solved to refine the translation.

After the endorsement on the back translation review, given by the correspondence author of the original scale (JY), the Italian scale version was tested on voluntary patients to ensure that the language and concepts expressed were clearly understandable (i.e. pilot testing). Thus, the translation was given to ten voluntary outpatients, using a convenience sampling. The patients have filled the translated Dyspnoea-12. Then, they have rated the clarity of each item, using a Likert scale from one to five (1=completely not clear; 5=completely clear). Further, the project manager has also asked them four questions aimed to check their comprehension of each translated items. The questions were: (a) Do you understand this? (b) What does this mean to you? (c) Can you explain it in your own words? (d) Can you suggest any alternative wordings?

The answers to these questions, along with any other relevant comments and suggestions, were transcribed Verbatim and analysed using a narrative analysis technique (20) to summarize the main emerging themes into a report. The project manager has reviewed the pilot-testing report and any eventual issues. When each issue was solved, the translation was formatted into the same format as the English version, and sent to the correspondence author of the original scale for her final endorsement.

Phase two: quantitative and qualitative content validity

The translated Dyspnoea-12 was also tested for quantitative and qualitative content validity.

The quantitative content validity followed the methodology developed in the 1970s by Lawshe (21). The aim was to assess agreement among raters regarding how pertinent is each item in relation to the objective of its measurement. Qualitative content validity (i.e. face validity) aimed to explore patients understanding of the items and their views about the overall concept that they purport to measure (22).

The quantitative content validity was assessed using the viewpoints of a panel of experts, consisting in 20 raters (i.e. 12 physicians, eight nurses). Their evaluation was firstly based on a three-point Likert scale (1= not necessary; 2=useful but not essential; 3=essential) to computed the content validity ratio (CVR). Its formula is CVR=(Ne - N/2)/(N/2), in which the Ne is the number of raters indicating “essential” and N is the total number of raters (21). CVR could varies between +1 and -1. Higher score indicates further agreement among raters on the necessity to keep the evaluated item in the scale. Secondly, the panel of experts was asked to rate translated Dysponea-12 items in terms of its relevancy to the construct underlying the scale using a four-point ordinal scale (1=not relevant; 2=somewhat relevant; 3=quite relevant; 4=highly relevant). CVI was calculated both for the items level (I-CVIs) and for the scale-level (S-CVI). To obtain the relevancy of each item (I-CVIs), the number of those judging the item as relevant (i.e. ratings ≥3) was divided by the number of content experts. Thus, I-CVIs were computed as the number of experts giving a rating 3 or 4 to the relevancy of each item, divided by the total number of experts, and expressing the proportion of agreement on the relevancy of each item, where the index could range between zero and one (23). Furthermore, S-CVI was defined as the proportion of total items judged content validity (23), and it was computed as the average of the I-CVIs.

To obtain the qualitative content validity, the authors asked to the same panel of expert (n=20) to answer to three open-ended questions, transcribed Verbatim. The questions were aimed to explore the difficulty level of the items’ wording, desired relationship between items and the main objective of Dyspnoea-12, eventually to discuss about ambiguity and misinterpretations of items. All the answers were analysed using a narrative analysis (20) to summarize the main emerging themes.

Ethical considerations

This study obtained the approval from the Research & Ethical Committee of Ospedale San Raffaele (Italy) (Protocol n.112/INT/2016). The research methodology was in full accordance with international ethical principles, Italian legal and research ethics requirements for non-interventional studies. All the participants (i.e. patients, nurses, physicians, translators) were informed about the aims and the method of the study, and they were asked to provide written informed consent, as required in the Italian Legislative Decree n. 196 of 30th June 2003. Participants of each phase were also informed about the confidentiality of their responses and anonymity in data elaboration for the final report of the study.

Results

Phase one: cultural and linguistic validation

The consensus discussion lasted approximately 90 minutes. The characteristics of participants included in the consensus discussion are shown in Table 1. Participants were mainly male (n=5; 83,3%) and median age was 44,8 years (IQR=9,1). According to the combined translation technique (19), participants discussed the two prior translations and back-translations, trying to ensure the equivalence of the concepts. Finally, participants rated each translated item to assess consensus in the items’ wording choice. All ratings were higher than four on a five-point Likert scale (1=completely not agree; 5=completely agree). As shown in Table 2, the Fleiss’ K was 0,95 and it was computed considering two categories (i.e. 4 and 5 rates), 12 cases (i.e. items) and six raters.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics (Phase 1)

| N | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus discussion participants n = 6 | Gender | Male | 5 | 83,3 |

| Female | 1 | 16,7 | ||

| Profession Physician | 2 | 33,3 | ||

| Psychologist | 1 | 16,7 | ||

| Nurse | 2 | 33,3 | ||

| Retired | 1 | 16,7 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 6 | 100 | |

| Education | Master Degree | 4 | 66,6 | |

| Ph.D. | 2 | 33,4 | ||

| Median | IQR | |||

| Age (years) | 44,8 | 9,1 | ||

| N | % | |||

| Pilot testing participants n = 10 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 6 | 60 | |

| Female | 4 | 40 | ||

| Profession | Retired | 7 | 70 | |

| Employed | 3 | 30 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 8 | 80 | |

| Unmarried | 2 | 20 | ||

| Education | University | 4 | 40 | |

| High school | 4 | 40 | ||

| Lower than higher school | 2 | 20 | ||

| Principal disease | HF | 6 | 60 | |

| COPD | 4 | 40 | ||

| Median | IQR | |||

| Age (years) | 66,4 | 6,2 | ||

Table 2.

Consensus discussion and pilot testing Items’ ratings (Phase 1)

| N of rating=4 | N of rating=5 | Fleiss’ K# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus discussion items ratings | Item 1 | 0 | 6 | 0,95 | |

| (6 participants) | Item 2 | 0 | 6 | ||

| Item 3 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Item 4 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Item 5 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Item 6 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Item 7 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Item 8 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Item 9 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Item 10 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Item 11 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Item 12 | 0 | 6 | |||

| N of rating=3 | N of rating=4 | N of rating=5 | Fleiss’ K§ | ||

| Pilot testing items ratings (10 participants) | Item 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0,81 |

| Item 2 | 0 | 1 | 9 | ||

| Item 3 | 0 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Item 4 | 0 | 1 | 9 | ||

| Item 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Item 6 | 0 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Item 7 | 0 | 1 | 9 | ||

| Item 8 | 1 | 0 | 9 | ||

| Item 9 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Item 10 | 0 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Item 11 | 0 | 1 | 9 | ||

| Item 12 | 0 | 0 | 10 | ||

Legend:

# Fleiss’ K was computed considering 2 categories (i.e. rating=4; rating=5), 12 cases (i.e. 12 items) and 6 raters

§ Fleiss’ K was computed considering 3 categories (i.e. rating=3; rating=4; rating=5), 12 cases (i.e. 12 items) and 10 raters

Back-translation by an independent native English speaker did not show any significant differences with the original scale; thus the original scale developer endorsed the translated items. Pilot testing provided further information about the clarity of the wording of individual items (see table 1 for participant characteristics). The ratings indicated high agreement between the English and Italian meaning for each item (Fleiss’ K=0,81). Moreover, participants commented on the ‘simplicity’ in understanding the meaning of each item. The translated items of Phase 1 are show in Table 4 (i.e. items in italics).

Table 4.

CVR calculation

| Expert panel (N=20) | Ne | CVR | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

item 1 My breath does not go in all the way | |||

| (Non mi sento capace di respirare apieni polmoni) | 19 | 0,90 | Relevant |

|

item 2 My breathing requires more work | |||

| (Devo forzare il respiro per riempire i polmoni) | 18 | 0,80 | Relevant |

|

item 3 I feel short of breath | |||

| (Sento di avere il fiato corto) | 18 | 0,80 | Relevant |

|

item 4 I have difficulty catching my breath | |||

| (Ho difficoltà nel trattenere il respiro) | 18 | 0,80 | Relevant |

|

item 5 I cannot get enough air | |||

| (Non riesco a prendere aria a sufficienza) | 19 | 0,90 | Relevant |

|

item 6 My breathing is unconfortable | |||

| (Il mio respiro à fastidioso) | 20 | 1,00 | Relevant |

|

item 7 My breathing is exhausting | |||

| (Il mio respiro mi stanca) | 18 | 0,80 | Relevant |

|

item 8 My breathing makes me feel depressed | |||

| (Il mio respiro mi butta giù di morale) | 17 | 0,70 | Relevant |

|

item 9 My breathing makes me feel miserable | |||

| (Il mio respiro mi fa sentire di cattivo umore) | 19 | 0,90 | Relevant |

|

item 10 My breathing is distressing | |||

| (Il mio respiro mi stressa) | 20 | 1,00 | Relevant |

|

item 11 My breathing makes me agitated | |||

| (Il mio respiro non mi fa riposare bene) | 19 | 0,90 | Relevant |

|

item 12 My breathing is irritating | |||

| (Il mio respiro mi rende irritabile) | 20 | 1,00 | Relevant |

Note: Italian version is in italics

Phase two: quantitative and qualitative content validity

Twenty patients participated in phase two (see table 3 for characteristics). The first quantitative content validity was assessed by CVR calculation and indicted that all the items were considered relevant (all CVRs higher than 0,70) and appropriate (see table 5).

Table 3.

Participants characteristics (Phase 2)

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 11 | 55 |

| Female | 9 | 45 | |

| Profession | Physician | 12 | 60 |

| Nurse | 8 | 40 | |

| Marital status | Married | 17 | 85 |

| Unmarried | 3 | 15 | |

| Median | IQR | ||

| Age | 41,6 | 6,3 | |

Table 5.

Calculation of I-CVI and S-CVI.

| Expert panel (N=20) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant (ratings ≥3) | Not Relevant (ratings ≤2) | I-CVI | Interpretation | S-CVI | |

| item 1 | 18 | 2 | 0,90 | Appropriate | |

| item 2 | 17 | 3 | 0,85 | Appropriate | |

| item 3 | 18 | 2 | 0,90 | Appropriate | |

| item 4 | 17 | 3 | 0,85 | Appropriate | |

| item 5 | 19 | 1 | 0,95 | Appropriate | |

| item 6 | 20 | 0 | 1,00 | Appropriate | 0,90 |

| item 7 | 16 | 4 | 0,80 | Appropriate | |

| item 8 | 19 | 1 | 0,95 | Appropriate | |

| item 9 | 17 | 3 | 0,85 | Appropriate | |

| item 10 | 18 | 2 | 0,90 | Appropriate | |

| item 11 | 19 | 2 | 0,95 | Appropriate | |

| item 12 | 18 | 2 | 0,90 | Appropriate | |

The narrative analysis on the experts’ answers to the three open-ended questions shows two main themes: ‘usefulness’ and ‘outrightness’. For example, a comment (expert SC) that has shaped the theme ‘usefulness’ was: “[...] we need a scale like the one you are validating, due to it could be very useful to rapidly assess dyspnoea in our patients, identifying both the physical and emotional aspects, besides its severity”. Another example of comment that has shaped the theme ‘outrifhtness’ was (expert OG): “[...] Its brilliant, items are immediately understandable and direct”.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop and assess content validity of the Italian version of Dyspnoea-12. Thus, the methodology of this study was designed to ensure the best cultural and linguistic translation, maintaining the original concept equivalence (19). Indeed, the assessment of quantitative and qualitative Italian version content validity supported the translated version, providing a solid basis for future implementations in clinical and research settings.

The core of the standardized translation process (19) was the consensus discussion, where the experts forward-translated the previous two back-translated versions, discussing about the best cultural equivalence of the Italian translation. This methodology was in line with a previous Arabic translation of Dyspnoea-12 (11) , and as even in Italian translation there were no items or terms problematic to translate. This could be explained because Dyspnoea-12 items are easy to understand with clear concept elaboration and definitions shared between the author of the original version and the project manager of the target language. Moreover, the pilot testing confirmed the clarity of the translation.

Considering CVR evaluation, item 8 was the only item with a borderline value (i.e. 0,70), but considered to be relevant by from the panellists perspective. Furthermore, all items were high rated by the panellists for their pertinence evaluation (I-CVI and S-CVI). These results provide solid support to the Italian translated Dyspnoea-12. As with every cross-cultural and international collaborative studies, Dyspnoea-12 translation also required assessment for its qualitative content validity (24); which showed a good response from the panellists.

The main limitation of the adopted methodology is previously described in relation to the possible difficulty to reach agreement during the consensus discussion (25). However, we did not experience such difficulty since our consensus discussion reached a very good agreement level (Fleiss’ K=0,95). The main limitation is related to the nature of bilingual technique translation. It could be related to the possibility that bilingual people are acculturated to their host culture, so they could report different response from monolingual people during consensus discussion (25).

Future investigations could are needed to provide evidence of the Italian version of Dyspnoea-12, psychometric properties. Following that work, the validate Dyspnoea-12 Italian version may be used to investigate the relationships between dyspnoea and QoL, and other important psychosocial outcomes in patients with cardiorespiratory diseases, such as anxiety, depression and fatigue. It could be very useful especially when the direct measurement of dyspnoea is difficult, such the context of palliative care (e.g. patients with walking difficulties).

Conclusion

This study has represented a pivotal step to use Dyspnoea-12 amongst Italian patients. The translated Dyspnoea-12 was the main result of this study, assessed by a robust methodological translation and supported by a good quantitative and qualitative validity. This scale could have a number of future implication for both clinical practice (e.g., its use in outpatients or inpatients settings), and for researches purposes. Healthcare professionals should objectively assess their patients’ symptoms to implement tailored clinical pathways (26). Hence, future researches are needed to deeply investigate the Italian version of Dyspnoea-12 construct validity and its reliability, and to describe how dyspnoea components (i.e. physical and emotional) impact the life of patients with cardiorespiratory diseases.

References

- 1.Tan J-Y, Yorke J, Harle A, Smith J, Blackhall F, Pilling M, et al. Assessment of Breathlessness in Lung Cancer: Psychometric Properties of the Dyspnea-12 Questionnaire. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(2):208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yorke J, Moosavi SH, Shuldham C, Jones PW. Quantification of dyspnoea using descriptors: development and initial testing of the Dyspnoea-12. Thorax. 2010;65(1):21–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.118521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yorke J, Armstrong I. The assessment of breathlessness in pulmonary arterial hypertension: Reliability and validity of the Dyspnoea-12. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014 Dec;13(6):506–14. doi: 10.1177/1474515113514891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuman A, Gunnbjörnsdottir M, Tunsäter A, Nyström L, Franklin KA, Norrman E, et al. Dyspnea in relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression: A prospective population study. Respir Med. 2006;100(10):1843–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cully JA, Graham DP, Stanley MA, Ferguson CJ, Sharafkhaneh A, Souchek J, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbid anxiety or depression. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(4):312–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khadawardi H, Mura M. A simple dyspnoea scale as part of the assessment to predict outcome across chronic interstitial lung disease. Respirology. 2016;21(8) doi: 10.1111/resp.12945. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishiyama O, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, Kimura T, Kato K, Kataoka K, et al. A simple assessment of dyspnoea as a prognostic indicator in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(5):1067–72. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00152609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland AE, Hill CJ, Conron M, Munro P, McDonald CF. Short term improvement in exercise capacity and symptoms following exercise training in interstitial lung disease. Thorax. 2008;63(6):549–54. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.088070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fierro-Carrion G, Mahler DA, Ward J, Baird JC. Comparison of Continuous and Discrete Measurements of Dyspnea During Exercise in Patients With COPD and Normal Subjects. Chest. 2004;125(1):77–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A Self-complete Measure of Health Status for Chronic Air-flow Limitation: The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145(6):1321–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Gamal E, Yorke J, Al-Shwaiyat MKEA. Dyspnea-12-Arabic: Testing of an instrument to measure breathlessness in Arabic patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Hear Lung J Acute Crit Care. 2014;43(3):244–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yorke J, Russell A-M, Swigris J, Shuldham C, Haigh C, Rochnia N, et al. Assessment of dyspnea in asthma: validation of The Dyspnea-12. J Asthma. 2011;48(6):602–8. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.585412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yorke J, Swigris J, Russell A-M, Moosavi SH, Ng Man Kwong G, Longshaw M, et al. Dyspnea-12 Is a Valid and Reliable Measure of Breathlessness in Patients With Interstitial Lung Disease. Chest. 2011;139(1):159–64. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lareau SC, Meek PM, Roos PJ. Development and testing of the modified version of the pulmonary functional status and dyspnea questionnaire (PFSDQ-M) Heart Lung. 1998;27(3):159–68. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(98)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka K, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Nishiwaki Y, Uchitomi Y. Development and validation of the Cancer Dyspnoea Scale: a multidimensional, brief, self-rating scale. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(4):800–5. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uronis HE, Shelby RA, Currow DC, Ahmedzai SH, Bosworth HB, Coan A, et al. Assessment of the psychometric properties of an English version of the cancer dyspnea scale in people with advanced lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(5):741–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chavez CA, Ski CF, Thompson DR. Psychometric Properties of the Cardiac Depression Scale: A Systematic Review. Hear Lung Circ. 2014;23(7):610–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brislin RW. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1(3):185–216. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones PS, Lee JW, Phillips LR, Zhang XE, Jaceldo KB. An adaptation of Brislin’s translation model for cross-cultural research. Nurs Res. 2001;50(5):300–4. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorne S. Data analysis in qualitative research. Evid Based Nurs. 2000;3(3):68–70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawshe C. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. 1975;28:563–75. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holden RR, Holden R. R. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. Face Validity. In: The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. 4th ed; pp. 637–638. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35(6):382–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maneesriwongul W, Dixon JK. Instrument translation process: a methods review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(2):175–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cha E-S, Kim KH, Erlen JA. Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: issues and techniques. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(4):386–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caruso R, Fida R, Sili A, Arrigoni C. Towards an integrated model of nursing competence: an overview of the literature reviews and concept analysis. Prof Inferm. 2016;69(1):35–43. doi: 10.7429/pi.2016.691035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]