Abstract

Acute and chronic pain have an important socio-economical impact. In order to help physicians to choose the appropriate drug, especially for cancer pain, in 1986 WHO has developed a three-step analgesic “ladder” for cancer pain relief in adults. Later it has also been used for acute pain and chronic non-cancer pain. In step I nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are considered with or without adjuvants, in step II the use of weak opioids for mild-moderate pain, with or without NSAIDs and adjuvant, is suggested, while the step III is reserved to strong opioids for moderate-severe pain with or without non-opioids or adjuvants. In the last two decades, a better pathophysiology knowledge has improved pain management shifting our view from the pain ladder to a modern pain pyramid, in which drugs are selected not only on the basis of pain intensity, but mainly according to mechanisms underlying pain, including peripheral and spinal sensitization which is the main trigger of chronic pain. The best pharmacological approach has become multimodal, in which drugs belonging to different steps should be combined, matching the mechanisms of action with the type of pain. An important corollary of combining analgesic drugs with different mechanism of action is that proper matching achieves the same effect with lower doses, better outcome and fewer adverse effects. In this new perspective, fixed-dose pharmaceutical combinations of different drugs are very useful to fulfil pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and adherence criteria, enriching the pain pyramid of half-steps between the first and second step and between the second and third step. Hence, a new fixed combination of a NSAID with peripheral and central anti-infilammatory activities, such as dexketoprofen, and a weak opioid, such as tramadol, with double analgesic activity in the spinal cord as an opioid and, at the same time, on the descending modulatory pathways, is expected to cover a wide range of acute and recurrent painful conditions, ranging from nociceptive inflammatory pain to neuropathic pain of moderate/severe intensity. In this review we evaluate the rationale that justifies its use as new class of pharmacological modality to treat pain accordingly also to a more update view of WHO pain ladder. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: tramadol, dexketoprofen, pain, acute pain, chronic pain, pharmacological treatment

Background

Acute and chronic pain are continuing to being an issue since several years with a even higher socio-economical impact both in Europe (1) and in USA (2).

Since 1986 the WHO analgesic ladder has been developed (3) as an educational and clinical tool to treat chronic pain, at the beginning for cancer pain and subsequently used also for acute pain and chronic non cancer pain.

It is structured with the “famous” three steps of pharmacological therapy:

- step I: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen are involved with or without adjuvants,

- step II: weak opioids mild-moderate pain +/- non opioids +/- adjuvants,

- step III: strong opioids for moderate-severe pain +/- non opioids +/-adjuvants.

The purpose of the WHO ladder has been to increase awareness of the importance of treating pain using a relative limited number of inexpensive drugs in a stepwise approach. Furthermore it was designed in order to suggest the medication accordingly to the pain intensity independently of its pathophysiology. Finally, it also helped to legitimize the use of opioids and be familiar with the use, benefits, and side effect of these drugs.

In the last two decades pain management has improved a lot for a better knowledge of pain pathophysiology and for the use of new drugs more potent and effective; hence, WHO ladder has been revised and criticized in his old form (4-6) and new ways to adopt it is strongly suggested (6).

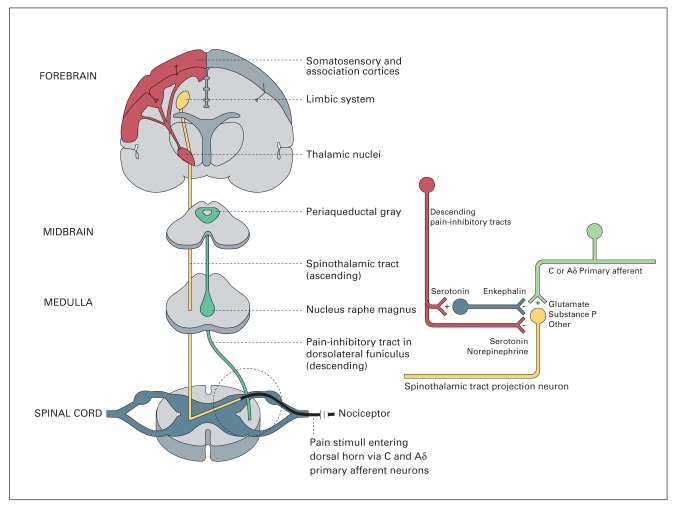

In 2010 Schaffer (7) proposed an adaptation of WHO ladder for acute pain and non-cancer pain introducing a IV step with invasive techniques such as nerve block, neurolytic and neurosurgical procedures such as brain stimuli. This adapted model also has been proposed for paediatric pain and acute postoperative pain. In her editorial in 2016, Jane Ballantyne (5) underlined all the nowadays problems related to the use of WHO ladder underlining and how it is important to look for and treat underlining pain pathophysiology and not only the pain intensity (6,8) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Different trajectories of patients reflecting different pathophysiological pain mechanisms (8)

The limitations of WHO ladder are even more evident when pain is beginning, during reacutization and after a trauma: in this case the best mechanism based approach has to address to three pathophysiological events: inflammatory response, pain control and prevention of central sensitization.

The WHO ladder would suggest to start with a drug and then change to opioids that could be increased if pain has not solved. In the “real” clinical practice, the best approach is to use a multimodal analgesia that could reduce peripheral inflammation and at the same time guarantee pain relief acting also on the spinal cord to reduce central sensitization (alsomaintained by central productionof prostaglandins (9,10) and counteracted by the release of serotonin and noradrenalin from descendent inhibitory pathways (11)). Finally, it is important that also in neuropathic pain, after an acute nervous lesion the blockade of prostaglandins peripheral hyperexpression can help to reduce pain and allodynia (12).

Hence, WHO three steps ladder is not adequate to suggest how to treat pain, especially when it begins. A “modern pain pyramid” (13) could be used to treat pain in its first phases considering to start soon with a mixed of first and second step in order to obtain all clinical effects useful not only to reduce pain, but also to better treat pain pathophysiology. It means that there are not only the three steps but also an “half-step” between first and second and between second and third one. The idea of half step (a mixed therapy with weak opioids and NSAID) could help physician to better treat a pain referred by patient as soon as it begins.

With this approach our goal is also to have a faster recovery reducing the risk of activation and maintaining of pain processes implied in chronic pain. In fact, it is well demonstrated (14,15) not only that chronic postoperative pain after acute lesion is more frequent in patients with a pro-inflammatory state, but also that in these patients tramadol and NSAIDs are better than tramadol and paracetamol to prevent chronic pain.

These clinical results are confirmed also by animal data. In mice it was demonstrated that the combination of NSAIDs and a weak opioid, such as tramadol, could decrease the postoperative hyperalgesia and prevent the pain sensitization for its anti-inflammatory activity, thanks to NSAIDs, and the inibitory activity of the descending noradrenergic pathways and the modulation of activity of microglia made by tramadol (16).

In this paper we would like to present the pathophysiological and pharmacological reasons to consider the association of dexketoprofen/tramadol as the first association for a “new” class of pharmacological treatment.

Tramadol/dexketoprofen a new combination to treat accurately pain pathophysiology. A pharmacological and clinical perspective

Tramadol/dexketoprofen is a new pharmacological association with analgesic activity. It is a combination of dexketoprofen, a NSAID with both peripheral and central antinflammatory activity, and tramadol, a weak opioid with double mechanism of action, partial agonism on the μ-opioid receptor and inhibition of monoamines (serotonine and noradrenaline) reuptake.

As the pharmacological associations currently available consist of the combination of opioids as codeine, tramadol, oxycodone with paracetamol, a molecule with minimal or clinically irrelevant peripheric antinflammatory activity, tramadol/dexketoprofen represents the first one of a new pharmacological class, in which the opioid activity has been combined with a drug with peripheral and central anti-inflammatory activity.

To understand the pharmacological profile of tramadol/dexketoprofen, it is necessary to recall the mechanism of action of the two single drugs.

Tramadol

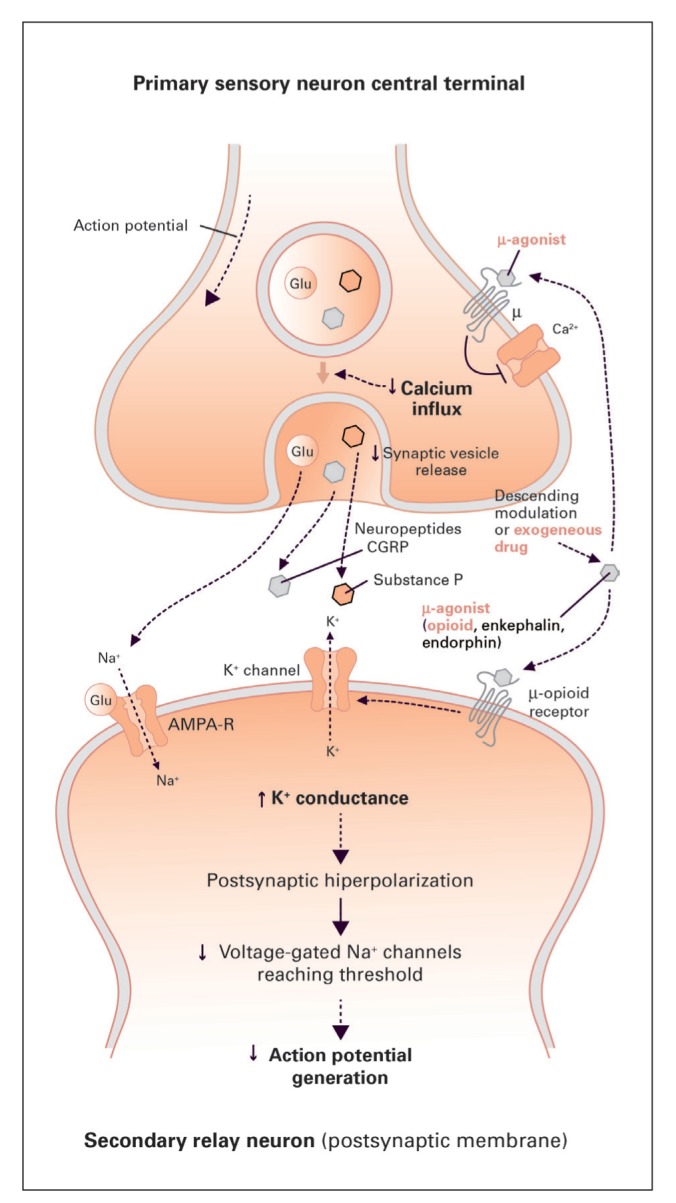

Tramadol has a double mechanism of action: activation of the μ-opioids receptors and inhibition of the reuptake of serotonine and noradrenaline (17,18). The effect on the μ-receptors is related to the main metabolite of tramadol, called O-desmetyl-tramadol, also known as M1, formed by citocrome P450 CYP2D6 (19). The affinity of M1 with receptor is lower compared to morphine, and it acts as a partial agonist, less effective than morphine, but safer in terms of adverse effects, such as respiratory depression and constipation. M1 acts on the μ-receptors localized in the posterior horns of spinal cord, where there is the synapsis between the nociceptive neuron, coming from the periphery, and the spino-thalamic neurons. The peripheral activation of peripheral nociceptive neurons leads to release of glutamate in the synapse, activating glutamate receptors on the spino-thalamic neuron, with consequent transmission of the nociceptive impulses towards the thalamus. The stimulation of μ-opioids receptors causes the inhibition of this synapsis, through both a pre-synaptic inhibition of the release of the neuro-transmettiters and an hyperpolarization of the spino-thalamic neuron, causing a stabilization and a partial refractoriness to peripheral stimuli (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of M1 on the spinal synapse. Through the activation of pre- and post-synaptic μ-receptors, M1 inhibits the transmission of nociceptive impulses coming from the periphery

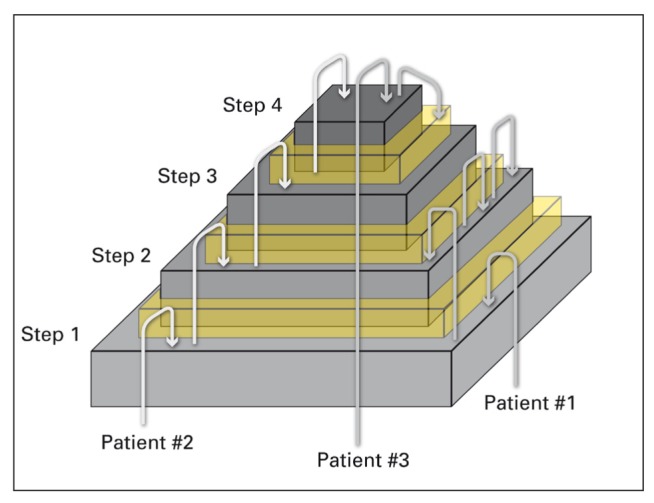

The second mechanism of action, mainly supported by the parental molecule of tramadol, is related to the inhibition of reuptake of the monoamines released by the descending tracts. Serotonine and noradrenaline act directly on their receptors located on the pre- and post-synaptic neurons or throught the activation of interneurons that release GABA or entogenous opioids inhibit synaptic transmission at the spinal level. Monoamines activity is stopped by their reuptake from the transporters, localised on the neurons AND on the glial cells. Hence, the inhibition of their reuptake causes a persistency of the monoamines in the synapse and of their analgesic effect (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Descending pathway releasing serotonine and noradrenaline

The double mechanism of action of tramadol is probably the key of its good analgesic activity not only in nociceptive pain, but also in neuropathic pain, where the involvement of the descending pathway in the attempt of counteracting ascending nociceptive impulses is relevant. In a recent metanalysis of the treatment of the neuropathic pain in adults, tramadol results as one of the most effective drug, immediately following tricyclic antidepressants and strong opioids, even if they were suggested only as third line, because of their higher adverse effects (20).

Dexketoprofen

Dexketoprofen, a non-selective NSAID, is the S(+)-enantiomer of ketoprofen. Compared to racemic ketoprofen, dexketoprofen has a greater antiflammatory activity and its ED50 dose is half of that needed with the racemic mixture (21). As ketoprofen, the pharmacological properties of dexketoprofen are of a moderate inhibition of COX-2 and an strong inhibition of COX-1 that allows the drug to have antinflammatory effects in the peripheral tissue and in spinal cord (22) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Anti-inflammatory activity of different NSAIDs through the evaluation of affinity with COX-1 and COX-2

| Drugs | IC80-COX-1 (μM) | IC80-COX-2 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 8.0 | >100 |

| Celecoxib | 28 | 6.0 |

| Diclofenac | 1.0 | 0.27 |

| Ibuprofen | 58 | 67 |

| Indomethacin | 0.46 | 5.0 |

| Ketoprofen | 1.0 | 22 |

| Ketorolac | 0.0034 | 0.4 |

| Naproxen | 110 | 260 |

| Nimesulide | 41 | 7.0 |

| Rofecoxib | >100 | 6.0 |

IC80-drug concentration required to inhibit 80% of COX-1 and COX-2 activity

Post-operative pain sperimental models demonstrated the inhibitory effect on the COX-1 in the spinal cord glial cells (23). As spinal cord glial cells activation contributes to the spinal sensitisation that can bring to the development of pain chronification, the central effect of dexketoprofen can be used not only in post-operative pain, but also whenever pain begins (i.e. acute and recurrent pain) and there is an high risk of chronicity.

Hence, dexketoprofen is a complete antinflammatory with peripheral action mainly through COX2 inhibition (22) (as it is well known that COX-2, overexpressed during peripheral inflammatory state, are the therapeutic target to modulate inflammation), and central action at spinal cord and glial cells through COX-1 inhibition (23).

Clinical synergistic effect of the association: 1+1=3

The obvious question arising from a pharmacological combination is whether the analgesic effect is the result of the sum of the effects of the single active principles or if it’s more: 1+1=3

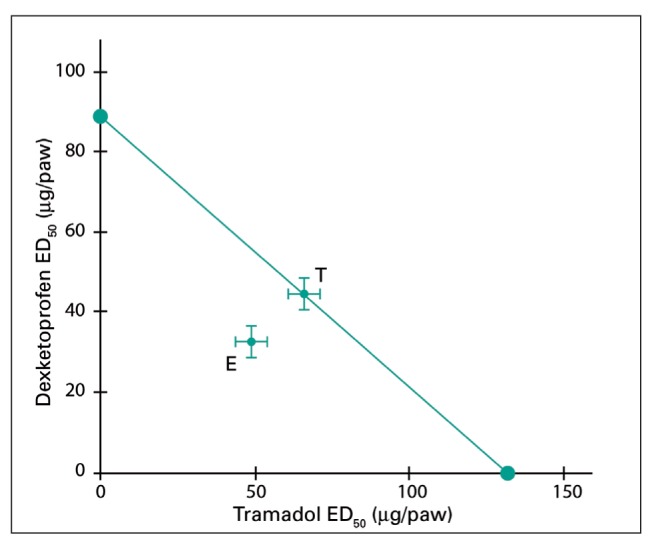

In the experimental setting, the demonstration of an additive/synergic effect of a combination passes through the construction of an isobologram, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of sinergistic effect of the association between dexketoprofen and tramadol (taken from Isiorda-Espinoza et al. 2014). Legend: T = theorical; E= Experimental

An isobologram is built as it follows: In the experimental setting we need to verify the necessary dose to obtain, for every single drug, a 50% reduction of pain (intercepta on the X axis for TRM and intercepta on the Y axis for DEX). We need to calculate which should be the theorical dosage (T) of the active drugs when combined in order to have a synargistic effect that is not only additive but rather multiplicative. Then, we need to evaluate which is the dosage of the two drugs in the experimental setting. If the interaction is synergistic, the dosage of individual drugs will correspond to a lower value than that shown in picture. So, to obtain the same analgesic effect we can use lower dosage of the single active ingredients, reducing the risk of adverse reactions.

In 2012, Miranda et al (25) demonstrated the synergy of tramadol and dexketoprofen on different parameters of nociceptive inflammatory pain in pre-clinical experimental models.

Clinical evidence of sinergistic effect of dexketoprofen/tramadol

Association of dexketoprofen/tramadol 25/75mg has shown clinically its synergistic effect in three clinical trials of acute postoperative pain (26-28) with also large sample size (more than 600 patients) (27).

Considering the type of surgery (hip arthroplasty, third molar extraction and hysterectomy) in which it was used, we can argue that its synergistic effect has been proven in all situation in which pain is related to a lesion and consequent mild inflammatory response.

These randomized double blind trials found a strong evidence of efficacy of the association of oral dexketoprefen/tramadol in fixed dose to treat moder-ate-to-severe acute pain. At the same time the safety profile of the association was in line with what previously known for the single drugs in monotherapy.

Another important aspect underlined by these trials is the rapid onset of this oral drug with a long lasting analgesic activity. It can be argued that the blockade of peripheral and central inflammation together with an opioid drug (furthermore with central activity on descending pathway) demonstrates its synergistic effect not only in reducing pain but also in prolonging the analgesia as it is also treating the causes of pain by itself.

The evidence of the synergistic effect of this association in acute pain has been also confirmed in the last months also by a meta-analysis (29).

These data underline how could be important to start with a fixed therapy that can act on all three aspects of pain whenever it begins, overcoming the WHO 3 steps ladder and adopting the “half step” ladder.

Conclusion

In this article we have reviewd the reasons why the fixed combination dexketoprofen/tramadol has a triple mechanism of action fighting against the peripheral inflammation, reducing the central sensitization and enhancing the activities of the antinociceptive descending paths.

Hence, the analgesic activity is the result of a synergic interaction between the two drugs, that can lead to spare few dose dependent adverse effects because of the lower doses needed of the single molecules

The peripheral antinflammatory effects of dexketorpofen and the good central activity of tramadol in neuropathic pain, make tramadol/dexketoprofen combination a very flexible tool for the treatment of different painful conditions with particular emphasis to the mixed forms of pain that are a relavant part of the clinical cases.

Furthermore, the central antinflammatory activity of dexketorpofen, associated with the inhibition of the activity of the spinal synapse by tramadol, make tramadol/dexketoprofen combination an ideal drug to be used to promptly treat whenever form of acute and recurrent pain of moderate/severe intensity, in order to counteract the establishment of processes that lead to chronic pain.

Finally, the use of a drug with 3 mechanisms of action could justify a new approach in treating pain as soon as it begins, adopting a new class of therapeuthical management overcoming the “classical” approach of WHO pain ladder. Traditionally WHO pain ladder suggests to start with a NSAIDs passing to opioids only after having demonstrated that it is not clinical effective. It implies that if patient continues to referring pain firstly we should increase the dosages of NSAID increasing the risks of side effects. With this fixed activity, we suggest, following Raffa et al suggestions (13), to adopt an “half ladder” between first and second step of WHO ladder, adopting a therapeuthical strategy that would like not only to reduce pain but also to move to a mechanism based approach to pain (8) as soon as pain begins through “half step ladder WHO”.

References

- 1.Breivik H, Eisenberg E, O’Brien T. OPENMinds. The individual and societal burden of chronic pain in Europe: the case for strategic prioritisation and action to improve knowledge and availability of appropriate care. BMC Public Health. 2013 Dec;24(13):1229. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain. 2012 Aug;13(8):715–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson. Effectiveness of the World Health Organization cancer pain relief guidelines: an integrative review. Journal of Pain Research. 2016;9:515–34. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S97759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballantyne JC, Kalso E, Stannard C. WHO analgesic ladder: a good concept gone astray. BMJ. 2016 Jan 6;352:i20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guiloff R. WHO analgesic ladder and Chronic pain: the need to search for treatable causes. BMJ. 2016;352:i597. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaffer Is the WHO analgesic ladder still valid? Canadian Family Physician. 2010;56 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vardeh D, Mannion RJ, Woolf CJ. Toward a Mechanism-Based Approach to Pain Diagnosis. J Pain. 2016 Sep;17(9 Suppl):T50–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson T, Narumiya S, Zeilhofer HU. Contribution of peripheral versus central EP1 prostaglandin receptors to inflammatory pain. Neurosci Lett. 2011 May 16;495(2):98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telleria-Diaz A, Schmidt M, Kreusch S, Neubert AK, Schache F, Vazquez E, Vanegas H, Schaible HG, Ebersberger A. Spinal antinociceptive effects of cyclooxygenase inhibition during inflammation: Involvement of prostaglandins and endocannabinoids. Pain. 2010 Jan;148(1):26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee YC1, Nassikas NJ, Clauw DJ. The role of the central nervous system in the generation and maintenance of chronic pain in rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011 Apr 28;13(2):211. doi: 10.1186/ar3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma W, Eisenach JC. Morphological and pharmacological evidence for the role of peripheral prostaglandins in the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurosci. 2002 Mar;15(6):1037–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raffa RB, Pergolizzi JV Jr. A modern analgesics pain ‘pyramid’. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014 Feb;39(1):4–6. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bugada D, Lavand’homme P, Ambrosoli AL, Cappelleri G, Saccani Jotti GM, Meschi T, Fanelli G, Allegri M. Inflammatory Status and Comorbidities on Pain Resolution and Persistent Postsurgical Pain after Inguinal Hernia Repair. Mediators Inflamm 2016. 2016:5830347. doi: 10.1155/2016/5830347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bugada D, Lavand’homme P, Ambrosoli AL, Klersy C, Braschi A, Fanelli G, Saccani Jotti GM, Allegri M. SIMPAR group. Effect of postoperative analgesia on acute and persistent postherniotomy pain: a randomized study. J Clin Anesth. 2015 Dec;27(8):658–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero Alejo. Antihypealgesic effect of dexketoprofen and tramadol in a model postoperative pain in mice effect on glial cell activation. Journal of Pharmacy And Pharmacology. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beakley BD, Kaye AM, Kaye AD. Tramadol, Pharmacology, Side Effects, and Serotonin Syndrome: A Review. Pain Physician. 2015 Jul-Aug;18(4):395–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minami K, Ogata J, Uezono Y. What is the main mechanism of tramadol? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2015 Oct;388(10):999–1007. doi: 10.1007/s00210-015-1167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minami K, Sudo Y, Miyano K, Murphy RS, Uezono Y. μ-Opioid receptor activation by tramadol and O-desmethyltramadol (M1) J Anesth. 2015 Jun;29(3):475–9. doi: 10.1007/s00540-014-1946-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, Gilron I, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Kamerman PR, Lund K, Moore A, Raja SN, Rice AS, Rowbotham M, Sena E, Siddall P, Smith BH, Wallace M. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Feb;14(2):162–73. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbanoj MJ, Antonijoan RM, Gich I. Clinical pharmacokinetics of dexketoprofen. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(4):245–62. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGurk M, Robinson P, Rajayogeswaran V, De Luca M, Casini A, Artigas R, Muñoz G, Mauleón D. Clinical comparison of dexketoprofen trometamol, ketoprofen, and placebo in postoperative dental pain. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998 Dec;38(12 Suppl):46S–54S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romero-Alejo E, Puig MM, Romero A. Antihyperalgesic effects of dexketoprofen and tramadol in a model of postoperative pain in mice effects on glial cell activation. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2016 Aug;68(8):1041–50. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isiordia-Espinoza MA, Pozos-Guillén A, Pérez-Urizar J, Chavarría-Bolaños D. Involvement of nitric oxide and ATP-sensitive potassium channels in the peripheral antinoceptive action of a tramadol-dexketoprofen combination in the formalin test. Drug Dev Res. 2014 Nov;75(7):449–54. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miranda HF, Romero MA, Puig MM. Antinociceptive and anti-exudative synergism between dexketoprofen and tramadol in a model of inflammatory pain in mice. Fundam-ClinPharmacol. 2012 Jun;26(3):373–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2010.00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McQuay HJ, Moore RA, Berta A, Gainutdinovs O, Fülesdi B, Porvaneckas N, Petronis S, Mitkovic M, Bucsi L, Samson L, Zegunis V, Ankin ML, Bertolotti M, Piza-Vallespir B, Cuadripani S, Contini MP, Nizzardo A. Randomized clinical trial of dexketoprofen/tramadol 25 mg/75 mg in moder-ate-to-severe pain after total hip arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2016 Feb;116(2):269–76. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev457. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore RA, Gay-Escoda C, Figueiredo R, Tóth-Bagi Z, Dietrich T, Milleri S, Torres-Lagares D, Hill CM, García-García A, Coulthard P, Wojtowicz A, Matenko D, Peñarrocha-Diago M, Cuadripani S, Piza-Vallespir B, Guerrero-Bayón C, Bertolotti M, Contini MP, Scartoni S, Nizzardo A, Capriati A, Maggi CA. Dexketoprofen/tramadol: randomised double-blind trial and confirmation of empirical theory of combination analgesics in acute pain. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:541. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore RA, McQuay HJ, Tomaszewski J, Raba G, Tutunaru D, Lietuviete N, Galad J, Hagymasy L, Melka D, Kotarski J, Rechberger T, Fülesdi B, Nizzardo A, Guerrero-Bayón C, Cuadripani S, Pizà-Vallespir B, Bertolotti M. Dexketoprofen/tramadol 25 mg/75 mg: randomised double-blind trial in moderate-to-severe acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. BMC Anesthesiol. 2016 Jan;22(16):9. doi: 10.1186/s12871-016-0174-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derry S, Cooper TE, Phillips T. Single fixed-dose oral dexketoprofen plus tramadol for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Sep 22;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012232.pub2. CD012232 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]