Abstract

Background

Humanity has become largely dependent on artemisinin derivatives for both the treatment and control of malaria, with few alternatives available. A Plasmodium falciparum phenotype with delayed parasite clearance during artemisinin-based combination therapy has established in Southeast Asia, and is emerging elsewhere. Therefore, we must know how fast, and by how much, artemisinin-resistance can strengthen.

Methods

P. falciparum was subjected to discontinuous in vivo artemisinin drug pressure by capitalizing on a novel model that allows for long-lasting, high-parasite loads. Intravenous artesunate was administered, using either single flash-doses or a 2-day regimen, to P. falciparum-infected humanized NOD/SCID IL-2Rγ−/−immunocompromised mice, with progressive dose increments as parasites recovered. The parasite’s response to artemisinins and other available anti-malarial compounds was characterized in vivo and in vitro.

Results

Artemisinin resistance evolved very rapidly up to extreme, near-lethal doses of artesunate (240 mg/kg), an increase of > 3000-fold in the effective in vivo dose, far above resistance levels reported from the field. Artemisinin resistance selection was reproducible, occurring in 80% and 41% of mice treated with flash-dose and 2-day regimens, respectively, and the resistance phenotype was stable. Measuring in vitro sensitivity proved inappropriate as an early marker of resistance, as IC50 remained stable despite in vivo resistance up to 30 mg/kg (ART-S: 10.7 nM (95% CI 10.2–11.2) vs. ART-R30: 11.5 nM (6.6–16.9), F = 0.525, p = 0.47). However, when in vivo resistance strengthened further, IC50 increased 10-fold (ART-R240 100.3 nM (92.9–118.4), F = 304.8, p < 0.0001), reaching a level much higher than ever seen in clinical samples. Artemisinin resistance in this African P. falciparum strain was not associated with mutations in kelch-13, casting doubt over the universality of this genetic marker for resistance screening. Remarkably, despite exclusive exposure to artesunate, full resistance to quinine, the only other drug sufficiently fast-acting to deal with severe malaria, evolved independently in two parasite lines exposed to different artesunate regimens in vivo, and was confirmed in vitro.

Conclusion

P. falciparum has the potential to evolve extreme artemisinin resistance and more complex patterns of multidrug resistance than anticipated. If resistance in the field continues to advance along this trajectory, we will be left with a limited choice of suboptimal treatments for acute malaria, and no satisfactory option for severe malaria.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12916-018-1156-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Malaria, P. falciparum, Artemisinin, Resistance, Artesunate, Quinine, NSG mice

Background

Artemisinin (ART) derivatives have become the keystone of malaria treatment and control [1]. ART has the advantage of killing all asexual blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum parasites, as well as affecting sexual development [2], resulting in rapid clinical and parasitological cure at an individual level, and a reduction in malaria transmission rates on a public health scale. All currently recommended first- and second-line treatments for uncomplicated malaria are a combination of ART with an unrelated antimalarial (artemisinin-based combination therapy, ACT) [1]. For severe malaria, artesunate (a type of ART; AS) is the first-line treatment, and quinine is the only available alternative [1]. Malaria control is thus highly reliant on ART, and adequate replacements are not forthcoming [3].

Historically, Southeast Asia has been the epicenter of malaria drug-resistance development – resistance to all major antimalarials has emerged there. P. falciparum resistance to ART (ART-R) given as part of ACT, was first reported from western Cambodia in 2008 [2, 4] and has already spread across the Greater Mekong subregion [5–11]. The ART-R phenotype is recognized clinically as a prolongation of parasitemia clearance as measured by peripheral blood smears (delayed parasite clearance time; DPCT) in patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Unexplained slow parasite clearance times have been reported with high frequency among Ugandan children treated with intravenous AS for severe malaria [12] and in East Africa, where residual submicroscopic parasitemia after ACT has been reported [13].

Infections with DPCT still show some therapeutic response to ART. Frank ART-R, a situation where ART would fail to cause an appreciable reduction of parasite levels in patients’ blood, has not yet been documented [5, 14]. Concerningly, reports are starting to emerge of multidrug-resistant malaria with treatment failures to ART and other key drugs, including quinine [15, 16].

Understanding ART-R has proved challenging both in the field and the laboratory [5, 6, 17–20]. In contrast to other antimalarials, no significant correlation between clinical response to ART and conventional in vitro determination of the 50% drug inhibitory concentration (IC50) is seen [5, 6]. For in vivo studies, only non-human malaria parasites that infect rodents have been available [21, 22]. Recently, however, substantial progress has been made. A series of in vitro and clinical studies have characterized the variable susceptibility of different parasite blood-stages to ART [23] and identified kelch-13 as an important P. falciparum gene associated with ART-R [10]. Besides kelch-13, these studies (including genome wide association studies; GWAS) [24], associated a number of other malaria parasite genes, such as RAD5 (which lies within 10 kb of kelch-13), ferredoxin, tetratricopeptide, and nt1, with ART-R. The altered regulation of many genes and metabolic pathways rather than a single gene polymorphism might be responsible for the ART-R phenotype [25–28]. The ring-stage survival (RSA) and trophozoite maturation inhibition assays have been developed following the observation of stage-specific susceptibility to ART, and are more sensitive at detecting decreased ART responsiveness than conventional laboratory methods [29, 30].

Despite the advances made, we have no way to foretell if P. falciparum can evolve beyond DPCT towards higher, more troublesome, levels of resistance. The successive loss of other antimalarial compounds to the rising tide of resistance, together with the remarkable potency of ART, has led to a worldwide switch to ACT. The consequences of this major shift in drug pressure on the P. falciparum genome, particularly the speed and strength with which ART-R might evolve, are difficult to gauge using available models.

Having developed a novel host that facilitates in vivo studies with P. falciparum [31, 32] – the Pf- NSG model grafted with human erythrocytes (huRBC), which allows high, long-lasting P. falciparum loads – we systematically assessed the resilience of P. falciparum in the face of defined ART exposure in vivo and characterized the resulting phenotype, particularly the drug-sensitivity profile, using both in vivo and in vitro methods concurrently.

We saw a remarkably rapid selection of very high-grade, stable resistance to ART with a delayed shift in IC50. Remarkably, despite exclusive exposure of the parasite to AS, strong co-resistance to quinine also developed in the same strain. Once again, P. falciparum has demonstrated its adaptability and proven its rank as one of humanity’s greatest challenges.

Methods

Mice

Four- to six-week-old male and female NOD/SCID IL-2Rγ−/− (NSG) mice (Charles River, France) were housed in sterile isolators and supplied autoclaved tap water with a γ-irradiated pelleted diet ad libitum. They were manipulated under pathogen-free conditions using a laminar-flux hood.

Human erythrocytes (huRBC)

HuRBC were used as host-cells for all in vitro and in vivo experiments. Packed huRBC were provided by the French Blood Bank (Etablissement Français du Sang, France) and taken from donors with no history of Malaria. HuRBC were suspended in SAGM (Saline, Adenine, Glucose, Mannitol solution) and kept at 4 °C for a maximum of 2 weeks. Before injection, huRBC were washed thrice in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 1 mg of hypoxanthine per liter (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and warmed for 10 min to 37 °C.

P. falciparum parasites and culture

The P. falciparum Uganda Palo Alto Marburg strain (FUP/CB or PAM) was used for all experiments [33]. This pan-sensitive strain is used as a laboratory reference for antimalarial assays [34, 35]. Over time, strains with different levels of ART-R were cryopreserved using the glycerol/sorbitol method as described [36]. Parasites were cultured in vitro with 5% hematocrit, at 37 °C with 5% CO2, using RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco-BRL) with 35 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich), 24 mM NaHCO3, 10% albumax (Gibco-BRL), and 1 mg/L of hypoxanthine (Sigma-Aldrich). When required, cultures were synchronized by either plasmagel (Roger Bellon, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) flotation [37] or exposure to 5% sorbitol (Sigma-Aldrich) [38]. At regular intervals, cultures were tested for Mycoplasma contamination using PCR.

In vivo replication of P. falciparum in the NSG-IV model

P. falciparum was maintained in huRBC grafted in NSG immunocompromised mice undergoing additional modulation of innate defenses using clodronate-containing liposomes, as described previously [31, 32] (‘Pf-NSG’ model). The proportion of huRBC in mouse blood (chimerism) was measured during experiments every 6 ± 4.5 days (mean ± standard deviation (SD)) by flow cytometry (Facscalibur, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) using a FITC-labeled anti-human glycophorin monoclonal antibody (Dako, Denmark). Human erythrocytes were found to constitute 77.4% ± 19.9% (mean ± SD) of erythrocytes in mouse blood during periods of drug pressure. Mice were inoculated intravenously with 300 μL of 1% non-synchronized P. falciparum-infected huRBC. Follow-up of infection was performed by daily Giemsa-stained thin blood films drawn from the tail vein. In this paper, we report parasitemia as a percentage of all erythrocytes found in mouse peripheral blood; the true percentage of huRBC parasitized in the mice is higher, proportional to the level of chimerism, because murine erythrocytes cannot be infected but were included in counts.

Estimates of the total parasite biomass in each mouse were calculated based on the mean corpuscular volume of mouse erythrocytes (45 fL), the mean corpuscular volume of huRBC (86 fL), hematocrit in the mice of 0.7, weight of NSG mice (25 g), and a conservative estimate of 5.5 mL of blood per 100 g of mouse weight using the following equation:

In vivo induction of drug resistance

Mice were initially infected with drug-naïve parasites from in vitro culture of cryopreserved stabilates and subsequently put under discontinuous sub-therapeutic AS drug pressure. Sodium AS (a gift from Sigma-Tau, Italy) was dissolved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in RPMI-1640 (stock solution 30 mg/mL) each day of injection, then diluted 10-fold in RPMI-1640, sterilized through a 0.22 μm Millex filter (Millipore, MA, USA), further diluted in sterile RPMI-1640 as appropriate, and delivered intravenously via the retro-orbital sinus.

For the single-dose protocol, one dose of AS (ranging from 2.4 mg/kg to 240 mg/kg) was given, then parasitemia was monitored every 24 h and allowed to recover back to pre-treatment levels (AS pressure cycle; APC) before a further dose of AS was administered. For the 2-day protocol, two doses of AS (starting at 2.4 mg/kg/injection up to 80 mg/kg/injection) were delivered 24 h apart, then parasitemia was monitored every 24 h and was allowed to recover back to pre-treatment levels (APC) before a further two doses of AS were given (i.e., for a 2-day dose of 2.4 mg/kg, the mouse was injected with a total of 4.8 mg/kg AS per APC). The length of APC varied from case to case. When parasitemia failed to drop significantly (see below) after exposure to a given dose, the concentration was increased. The parasite strain used for the 2-day protocol had already developed resistance to a single dose of 30 mg/kg AS, and was then subjected to the 2-day regimen starting at 2.4 mg/kg/injection. Parasite strains were named ART-Rx, where x is the dose of AS (in mg/kg) to which resistance was established in that strain.

To determine what should be considered a significant drop in parasitemia, the normal day-to-day fluctuation of parasitemia was calculated from 13 non-drug-exposed NSG-IV mice (geometric mean of variability ± 18.3%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 12.5–27%). Taken from this, the parasite was deemed to be resistant to a given dose when parasitemia failed to drop more than 27% by the next day (all reported measures of parasite reduction are from the day after drug administration). We analyzed the drop in parasitemia seen among five mice infected with the PAM-sensitive strain the day after a single administration of intravenous AS to define a ‘sensitive response’ to AS in this model. The mean reduction was 78.4% with a SD of 18.2%. We conservatively chose a drop in parasitemia greater than 60.2%, corresponding to the mean (1 SD) as the definition of a sensitive response to guide decisions about dosing. For definitive statistical comparisons of parasitemia responses, a paired t test was used. Stability of resistance was determined when required by re-challenging the parasite strain in its new host with the dose of drug to which it had last shown resistance. The ART-R P. falciparum strain was continuously perpetuated in vivo by sub-inoculation directly from one mouse to another by the intravenous route, except where otherwise indicated.

In vitro drug sensitivity assays

The primary technique used to determine IC50 was the double-site enzyme-linked pLDH immunodetection assay, as previously described [39]. The 3H-hypoxanthine isotopic method [40] was used as a secondary confirmatory assay. All in vitro results shown below come from the double-site enzyme-linked pLDH immunodetection assay.

For both methods, P. falciparum parasites at 0.05% parasitemia, synchronized at ring stage, were incubated at 2% hematocrit in 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc, Sigma-Aldrich) with serial dilutions of various anti-malarial drugs in 200 μL of complete culture medium at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 72 h. Non-drug-exposed wells were used as positive controls, and wells containing non-infected huRBC served as negative controls.

Stock solutions of the drugs (5 mL,1.5 mg/mL) were prepared by dissolving sodium AS (gift from Sigma-Tau), chloroquine sulphate (Rhone-Poulenc-Rorer, Vitry, France), dihydroartemisinin (DHA; Sigma-Tau), pyrimethamine (ICN Biochemicals, Aurora, Ohio), quinine hydrochloride (Sanofi, Montpellier, France), lumefantrine (Sigma-Aldrich), and mefloquine hydrochloride (Hoffman-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in 10% DMSO in RPMI-1640, whereas amodiaquine dihydrochloride and halofantrine hydrochloride were dissolved in 30% DMSO in RPMI-1640. Drug solutions were diluted 10-fold in RPMI-1640, sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 μM filter, and serially diluted in a 96-well incubation plate.

IC50 values were determined by performing a four-parameters, variable slope, non-linear regression analysis taking the least-squares fit without constraints, using Graph Pad Prism 6 software. Comparison of IC50 values and hillslopes was performed using the extra sum-of-squares F test (GraphPad, Inc., CA, USA).

In vivo co-resistance studies

Mice infected with the ART-R240 strain were given either single treatments or combinations of the following regimens: three doses of quinine hydrochloride 73 mg/kg every 8 h intravenously, four doses of halofantrine hydrochloride 1 mg/kg every 24 h intravenously, one dose of amodiaquine dihydrochloride 73 mg/kg orally (delivered by oro-gastric canula), one dose of chloroquine sulphate 73 mg/kg orally, or one dose of mefloquine hydrochloride 50 mg/kg intra-peritoneally, as previously described [41]. Stock solutions were made by dissolving 150 mg of quinine, chloroquine, and mefloquine in 5 mL of 10% DMSO, 150 mg of amodiaquine in 30% DMSO, and 60 mg of halofantrine in 30% DMSO, then dissolved 10-fold in RPMI-1640, and sterilized by filtration before being made up to the final concentration.

Determination of mouse plasma drug concentrations

Plasma concentrations of AS and DHA in blood samples (40–60 μL) collected from the retro-orbital sinus in four mice at 1, 2, and 4 h post intravenous drug administration were determined by reversed phase liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an adaptation of the previously described method [42]. Murine plasma was purified by protein precipitation with acetonitrile, evaporation, and reconstitution in 10 mM ammonium formate/methanol (1:1) adjusted to pH 3.9 with formic acid. Separations were done on a 2.1 mm × 50 mm Atlantis dC18 3 μm analytical column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The chromatographic system (CTC Analytics AG, Zwingen, Switzerland) was coupled to a triple stage quadrupole Thermo Quantum Discovery Max mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization interface (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The selected mass transitions were m/z 221.1 → 163.1, with a collision energy of 14 eV for AS and DHA, and m/z 226.2 → 168.1, with a collision energy of 20 eV for the stable isotope-labeled internal standard DHA-13CD4. Inter-assay precision obtained with plasma QC samples at 30, 300, and 3000 ng/mL of DHA and AS were 1.3, 2.1, 11.3%, and 7.3, 4.7, and 10.8%, respectively. Mean absolute deviation from nominal values of QC samples (30, 300, and 3000 ng/mL) during the analysis were 5.4, 5.9, and 1.3% and 3.8, 9.7, and 2.1%, for DHA and AS, respectively. The lower limit of quantification was 2 ng/mL. The laboratory participates in the External Quality Control program for anti-malarial drugs (http://www.wwarn.org/).

Restriction fragment length polymorphism

ART-R P. falciparum DNA was isolated from parasitized blood using QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Limburg, Netherlands). A non-synonymous point mutation of ubp1 in P. chabaudi (PCHAS020720) was reported by others [43] as being a marker of ART resistance in a rodent model. The orthologous gene in P. falciparum (PF3D7_0104300) is conserved and was amplified using the primers (500 nM) forward: 5’-TACAGGCTTTATATAGTACAGTGTC-3′, reverse: 5’-TTTTCGTTCGTACTTATAGGCACAGG-3′, and AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase (1 U) (Hoffman-La Roche). The 451 bp PCR fragment was purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Polymorphisms in PF3D7_0104300 were assessed by digesting the PCR fragment with the restriction enzymes Mae III for V3275F and Rsa I for V3306F, corresponding to V2697F and V2728F in PCHAS 020720, respectively.

Genetic sequencing

Genes of interest in P. falciparum coding for the proteins RAD5, cNBP, RPB9, PK7, FP2A, Pfg27, Pfcrt, and Pfnhe, two fragments overlapping the kelch-13 propeller domain [44–46], and Pfmdr1 gene were analyzed by PCR-sequencing. Primers used for Pfmdr1 PCR and sequencing were previously described by Basco and Ringwald [47], and Pfmdr1 gene copy analysis was performed as previously described [48]. For Pfnhe, two primer couples were designed for nested PCR on the basis of the 3D7 sequence. Control samples were taken from in vitro cultures of the P. falciparum 3D7 strain, and the sensitive progenitor PAM strain prior to any ART exposure (PAMwt); for the RAD5 experiment, additional control clinical isolates collected in the late 1990s were used from Brazil, Comoro Islands, Senegal, and Thailand. Experimental samples were recovered from P. falciparum-infected mice at various points during the ART resistance induction process (NSG415, 416, 424, 433, and 440). Genomic DNA was prepared using QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, in 50 μL of Milli-Q water; 1 μL of DNA was PCR-amplified with 500 nM of the corresponding forward and reverse primers (Additional file 1), 0.8 mM dNTPs, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Hoffman-La Roche) in a volume of 50 μL with the following cycling program: 2 min at 94 °C, 30 cycles of 15 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 57 °C, 45 s at 72 °C, and a final extension of 2 min at 72 °C. The total contents of the reaction were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The amplicons were extracted from the gel using the QIAquick® gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Concentration of the amplicons was measured by NanoDrop (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc.) at 260 nm wavelength before sequencing of both strands was performed (Plateforme de séquençage, Institut Cochin, Paris/Eurofins MWG Operon). Sequences were analyzed with DNAstar software (DNAStar, Madison, WI, USA).

Results

Determination of the lowest effective dose (LED) for ART-sensitive progenitors

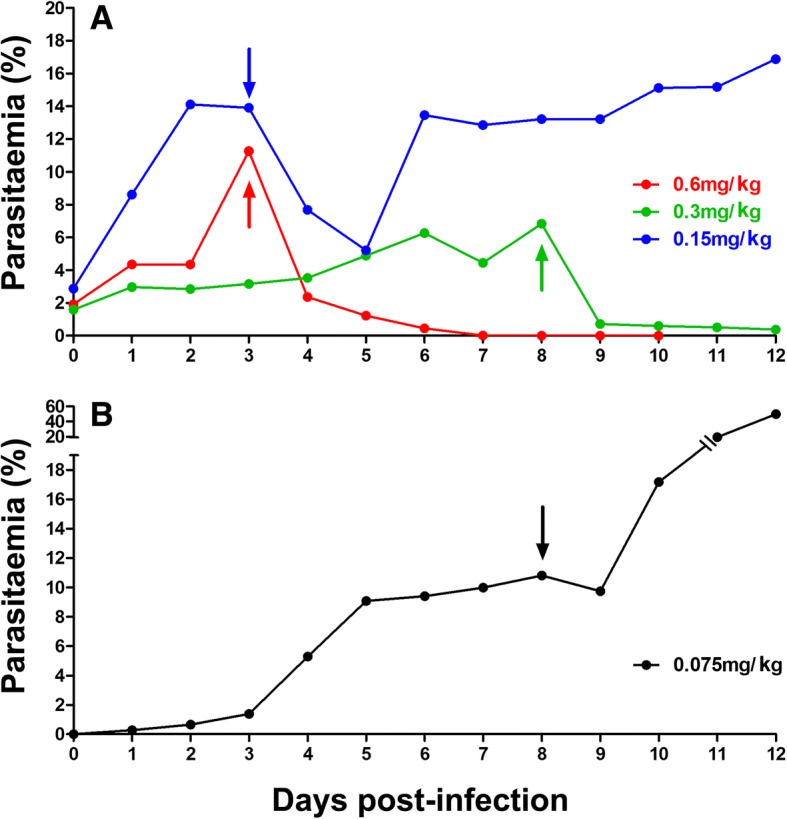

We infected seven mice with the PAM P. falciparum strain before any drug exposure to determine the LED. Single doses of 0.6, 0.3, and 0.15 mg/kg AS each caused a significant drop in parasitemia (> 27%, i.e., the upper 95% CI of normal fluctuation). Since 0.075 mg/kg AS failed to reduce parasitemia beyond normal day-to-day fluctuations, a single dose of 0.15 mg/kg AS (0.00375 mg AS/mouse) was established as the LED in this model (Fig. 1). Effective doses of AS produced pyknotic parasites as seen in humans (Additional file 2).

Fig. 1.

Determination of the lowest effective dose (LED). Parasitemia trends from individual NSG mice that each received a unique dose of (a) 0.6 mg/kg, 0.3 mg/kg, 0.15 mg/kg, or (b) 0.075 mg/kg of artesunate (AS) are shown. We infected mice with the Uganda Palo Alto Marburg (FUP/CB or PAM) progenitor strain before it was subjected to any drug pressure. Arrows indicate day of intravenous drug delivery. In panel a, day 0 represents the fourth day post-inoculation of mice. Results were reproducible in several mice treated at each dose

Rapid induction of high level ART resistance in P. falciparum

We applied intense, discontinuous, sub-curative AS drug pressure in vivo to high P. falciparum parasitemia in NSG mice using the intravenous route. After each drug exposure, parasitemia was allowed to recuperate back to pre-treatment levels (APC) and, once resistance was established, the AS dose was increased (Fig. 2 and Additional file 3). For the single-dose regimen, the median APC length was 4 days (range 2–14 days).

Fig. 2.

Examples of selection for single-dose artemisinin resistance. Demonstrative parasitemia trends as seen at different time points during the resistance-selection process are shown from mice that received single flash doses of (a) 15 mg/kg, (b) 120 mg/kg, or (c) 240 mg/kg artesunate. Arrows indicate day of intravenous drug delivery. Results were reproduced in several mice as indicated in Table 1 and Table S2A

During the single-dose regimen, after pre-conditioning of the drug-naïve parasites with 3 single doses of AS in one mouse, we passed the parasite line through 7 generations of mice by sub-inoculation, using 5, 9, 6, 1, 6, 10, and 6 mice in each generation, respectively (total 43).

In the first generation, we let parasites multiply to high parasitemias (25–35%) creating a pool of ~ 1.3 × 1010P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes. We saw resistance to 2.4 mg/kg AS after 3 APC in 1 out of 4 mice exposed to that dose, then to 3.3 mg/kg AS after 2 APCs in 1 out of 3 mice, and to 4 mg/kg AS in 2 out of 2 mice exposed to a mean 1.5 APC.

In the second generation, resistance to 3.3 mg/kg was established in another mouse (1 APC), and to 4 mg/kg in 2 further mice (mean 1.5 APC, range 1–2). Later, we confirmed 4 mg/kg resistance in a new host. Seeing as resistance was so forthcoming, we increased drug pressure readily to 15 mg/kg AS, to which indeed 4 out of 5 mice exposed became resistant (mean 5 APC, range 2–9) (Additional file 4).

Resistance to 30 mg/kg AS then emerged in 2 out of 4 mice exposed to that dose (mean 1.5 APC, range 1–2). However, it was not stable and, in the third generation, an average of 3.6 APC (range 2–5) was required before it was re-established (ART-R30). Subsequently, in 1 mouse, after applying variable-intensity drug pressure, resistance to 60 mg/kg AS was obtained (5 APC).

We confirmed the stability of resistance to 60 mg/kg AS (ART-R60) immediately after sub-inoculation into the fourth generation, and after just three further exposures to 120 mg/kg AS, the strain showed the first signs of resistance to that dose.

In the fifth generation, we observed resistance to 120 mg/kg AS (ART-R120) in all 4 mice exposed after an average of 3 APC (range 2–4). Then, in 1 mouse, the parasite went on to develop resistance against 240 mg/kg AS after 4 APC (78, 44, 60, and 13% reduction in parasitemia seen with each APC, respectively).

After sub-inoculation into the sixth generation, the parasite strain established resistance to 240 mg/kg AS in 4 out of 6 mice exposed to that dose (2.75 APC, 1–7).

In the seventh generation, resistance was immediately stable, after sub-inoculation, to 240 mg/kg AS in all 6 mice (ART-R240) (mean ± SD percentage drop in parasitemia of sensitive control 78.4% ± 18.2% vs. ART-R240 9.1% ± 6.3%; p = 0.0002).

Since further dose doubling would exceed the lethal dose for 50% of mice [41, 49], 240 mg/kg was the highest dose administered. We used NSG mice infected with the sensitive progenitor PAM strain as controls, and all treatments using the above doses were found effective. This represents a 3200-fold decrease in in vivo AS sensitivity, occurring within 51 APC over a 45-week period (Table 1, Additional file 2, Additional file 3, and Additional file 5). Further, we observed gametocytes in thin blood smears from mice infected with parasites expressing the ART-R phenotype (Additional file 6).

Table 1.

Number of artesunate pressure cycles (APC) used to select for single-dose resistance in individual mice

| Dose of Artesunate (mg/kg) | 2.4 | 3.3 | 4 | 15 | 30 | 60 | 120 | 240 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of APC required to reach resistance | 3 | 2 | 2, 3, 1, 2, 1 | 3, 9, 6, 2 | 1, 2, 4, 5, 3, 4, 2 | 5, 1 | 3, 3, 4, 2, 3, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2 | 4, 1, 7, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1 |

| Number of mice with resistance/total attempted | 1/4 | 1/3 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 7/8 | 2/2 | 11/11 | 11/15 |

The number of artesunate pressure cycles (APC) after which resistance was seen to a given dose in individual mice is tabulated. The proportion of mice with parasites that evolved resistance can be seen to increase as the resistance strengthened, and as ‘fitter’ parasites were selected out by successive sub-inoculations, until the maximum dose was reached. A full account of the selection process and evolution of ART-R for the single and 2-day regimens can be found in the supplementary information (Additional files 1, 2, 5 and 8)

Induction of resistance to a 2-day regimen

Two doses of the same AS concentration administered 24 h apart – a double dose (DD) – caused a significant reduction in parasitemia in animals in which a single dose of the same concentration had failed.

We started with a concentration of 2.4 mg/kg/dose for the DD regimen using a parasite strain already resistant to a single dose of 30 mg/kg AS. The ART-R30 strain became resistant to DD 2.4 mg/kg AS after just 1 APC. We passed the parasite line through four generations of mice with 6, 8, 3, and 4 mice in each generation, respectively. Once resistance was seen, we increased the dose concentration 2-fold, until reproducible resistance to DD 80 mg/kg AS (i.e., 160 mg/kg total) was achieved (ART-RDD80) (Fig. 3, Additional file 7, and Additional file 8) (mean ± SD percentage drop parasitemia of sensitive control 95.9% ± 5.7% vs. ART-RDD80 25.7% ± 0.6%; p = 0.03).

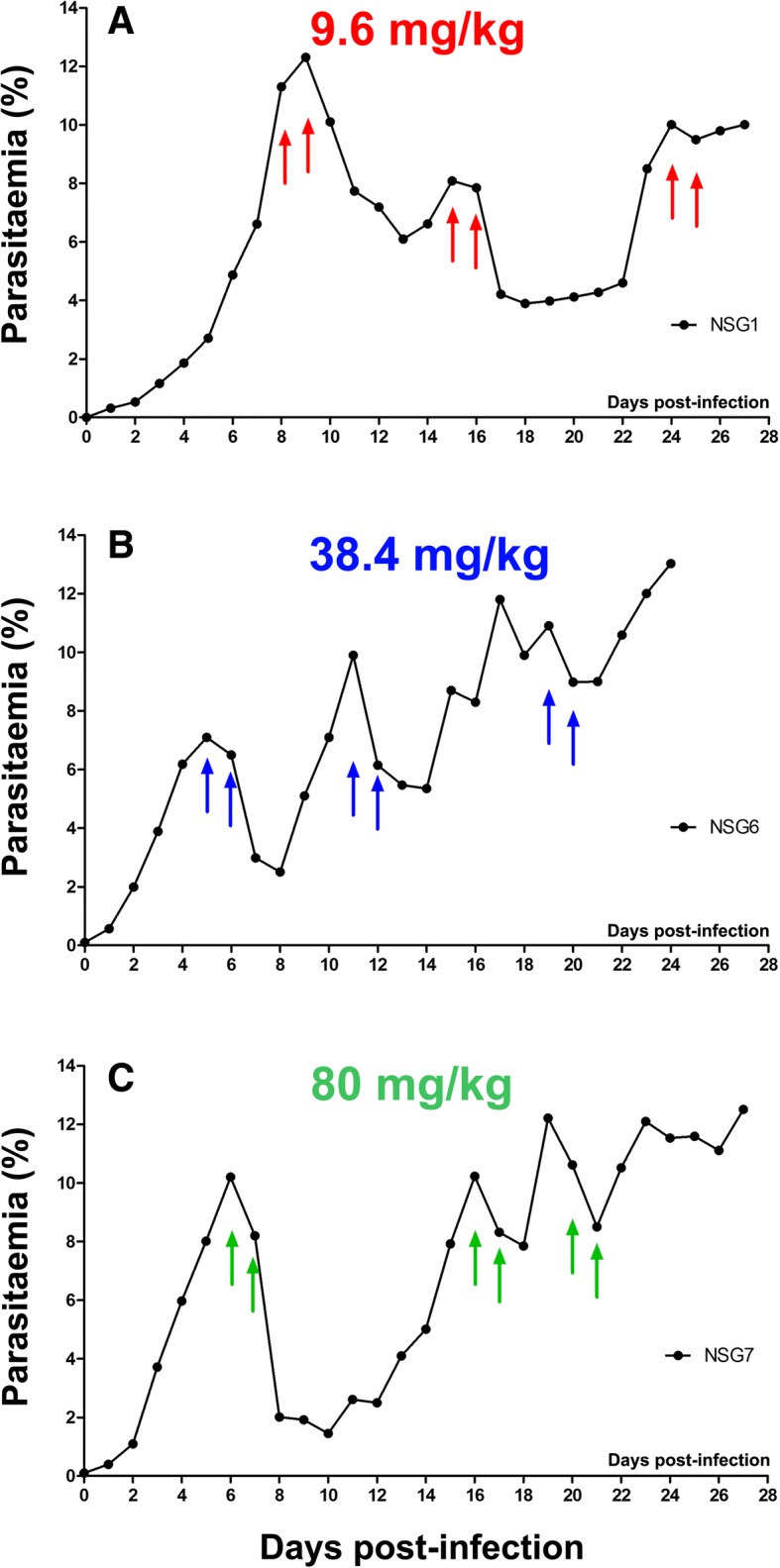

Fig. 3.

Examples of selection for double-dose artemisinin resistance. Demonstrative parasitemia trends as seen at different time points during the resistance selection process are shown from mice that received a 2-day regimen comprising two doses 24 h apart of (a) 9.6 mg/kg, (b) 38.4 mg/kg, or (c) 80 mg/kg artesunate (i.e., total of 19.2 mg/kg, 86.8 mg/kg, or 160 mg/kg AS per APC). Arrows indicate day of intravenous drug delivery. Results were reproduced in several mice as indicated in Table S2B

It was possible to select for resistance to the highest dose used in 41% of the mice that survived the 2-day protocol, in contrast with 80% of mice that underwent the single-dose protocol (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of mice used and outcome for both dosing regimens

| Total number of mice | Died before interpretable | Resistance seen against highest dose | Resistance not seen against highest dose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single dose No. | 43 | 8 | 28 | 7 |

| %a | 80% | 20% | ||

| Double dose No.b | 21 | 4 | 7 | 10 |

| %a | 41.2% | 58.8% |

aPercentages calculated excluding mice that died before significance

bDouble dose regimen began using parasites resistant to single dose 30 mg/kg

The total number of mice used to select for resistance against both single and 2-day doses of artesunate across all dose concentrations, and the proportion of mice in which resistance emerged to the highest dose used, are tabulated. In instances where mice were sub-inoculated with the parasite strain but either died before receiving any drug treatment or died within 24 h of drug treatment (precluding meaningful measurement of their parasitemia), they were termed to have died before becoming experimentally interpretable. Parasites subjected to the 2-day regimen of artesunate were less likely to become resistant

Verification of DHA concentration in mouse plasma

We measured levels of AS and DHA at 1 and 2 h post injection of 120 mg/kg AS in four ART-R120-infected mice (Additional file 9). Serum concentrations of DHA at 1 h were 3159, 3219, 1573, and 2423 ng/mL in each mouse, respectively, and we confirmed resistance to these levels on blood films drawn the following day. The mean t1/2 of DHA in the infected NSG-IV model was 36 min (range 20.9–53.2 min).

Stability of the ART-resistant phenotype

Stability was assessed in three different manners:

Transmission to new animals: The parasite was found to maintain stable AS resistance after sub-inoculation into fresh mice for 60 mg/kg AS in 1 out of 1 mouse, 120 mg/kg AS in 5 out of 11 mice, and 240 mg/kg AS in 6 out of 6 mice (Additional file 3).

Cryopreservation and in vitro growth: At various points, parasites resistant to a given AS concentration were cryopreserved and stored for 1–6 months, thawed, and then cultured in vitro for 8 to 12 days. After inoculation of cultured parasites into new mice, the ART-R30, ART-R120, and ART-R240 strains maintained their pre-freezing resistant phenotype (Fig. 4a, b).

Prolonged in vivo replication in the absence of drug pressure: We infected three mice with the ART-R120 strain, and confirmed resistance by administration of 120 mg/kg AS. The parasites were then allowed to grow in vivo without any drug pressure for 1 month. Upon re-treatment of the two surviving mice with 120 mg/kg AS, they both showed the same resistant response as had been seen 1 month prior (mean ± SD percentage drop in parasitemia, start: 10% ± 14.1% vs. end: 8.4% ± 11.8%; p = 0.94). The in vitro response also remained unchanged (IC50 AS: F = 0.03, p = 0.87; IC50 DHA: F = 1.1, p = 0.3) (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

Evidence for stability of artemisinin resistance. a Following cryopreservation of resistant parasites with unchanged IC50: parasitemia trends from mice infected with the ART-R30 strain following cryopreservation and cultivation in vitro are shown. Arrows indicate day of re-challenge with 30 mg/kg AS. b Following cryopreservation of parasites with increased IC50: parasitemia trends from animals infected with ART-R120 (orange) and ART-R240 (purple, pink) following cryopreservation and cultivation in vitro. Arrows indicate the day of re-challenge with either 120 or 240 mg/kg artesunate (AS). c In vitro response following in vivo replication without drug pressure: In vitro sensitivities for AS and dihydroartemisinin (DHA) measured for ART-R120 parasites grown ex vivo, that were sampled before and after 1 month of drug pressure-free in vivo replication (see d), are tabulated. d In vivo following drug free replication: We maintained the ART-R120 parasite in vivo for 4 weeks without drug pressure in three mice; parasitemia trends of the two mice that survived are shown (red, blue). Challenges performed before and after treatment with 120 mg/kg AS (arrows) show stability of the resistant phenotype. We employed a lower intensity huRBC grafting protocol for this experiment to increase mouse survival, which caused a drop in parasitemia in the interim

In vitro drug sensitivity profiles of ART-R parasites show a two-step pattern

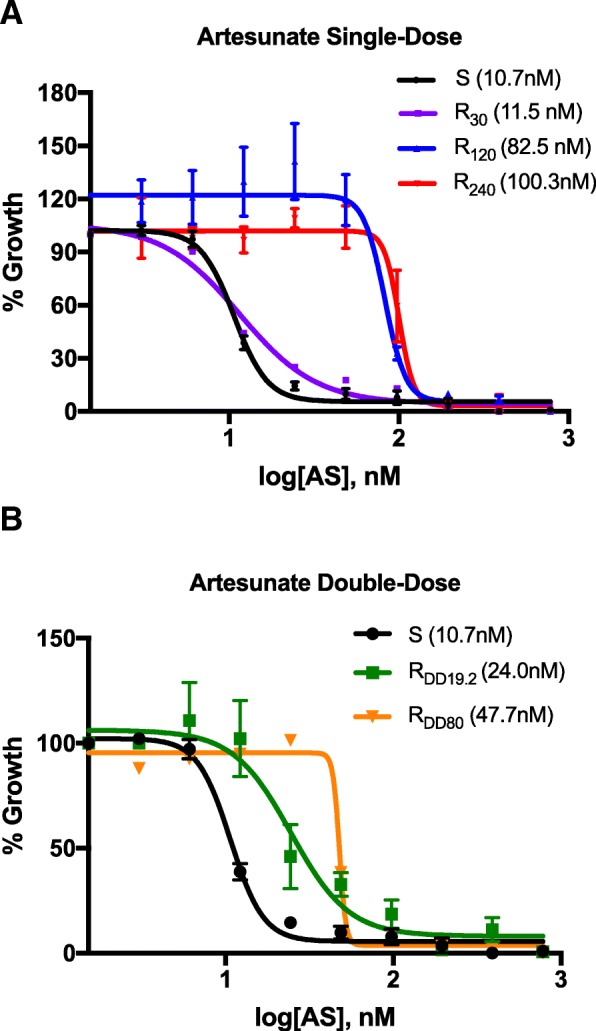

We monitored 50% IC50 values over the course of resistance development for both single-dose and 2-day regimens, and compared them to the sensitive progenitor.

The initial IC50 (95% CI) values for the sensitive strain to AS and DHA were 10.7 nM (10.2–11.2) and 13.8 nM (12.9–14.6), respectively. The ART-R30 strain did not show any increase in IC50 for AS (11.5 nM (6.6–16.9); F = 0.525, p = 0.47); however, there was a significant change in the slope of the curve compared to the sensitive control (hillslope − 4.4 (–6 to –3.6) vs. − 1.9 (–6.4 to –0.8); F = 7.5, p = 0.008). It was not until the strain became resistant to 120 mg/kg AS in vivo that the IC50 rose sharply for both AS (to 82.5 nM (69.5–95.8); F = 191.3, p < 0.0001) and DHA (to 54.6 nM (51.6–57.6); F = 300.3, p < 0.0001). The ART-R240 strain reached an IC50 of 100.3 nM (92.9–118.4) (F = 304.8, p < 0.0001) for AS.

In parasites submitted to a 2-day regimen, we saw the same pattern, with a delayed shift in IC50 (Fig. 5 and Additional file 10).

Fig. 5.

In vitro artesunate sensitivities at different levels of in vivo resistance. In vitro artesunate (AS) dose–response curves, with SD error bars, are shown for parasites resistant in vivo to (a) single dose AS 30 mg/kg (purple), 120 mg/kg (blue), and 240 mg/kg (red) or (b) 2-day regimen AS 19.2 mg/kg/dose (green) and 80 mg/kg/dose (orange), and compared to the artemisinin-sensitive progenitor strain (black). Mean IC50 values (nM) are indicated in parentheses

ART-R parasites are also resistant to quinine, amodiaquine, and halofantrine both in vivo and in vitro

Despite exclusive exposure to AS, the ART-R240 parasite strain showed markedly decreased responses to quinine, amodiaquine, and halofantrine. Indeed, the IC50 increased by 4.6-fold to quinine (49.7 nM (46.6–52.8) vs. 226.9 nM (145.8–392.1); F = 23.12, p < 0.0001), 3.8-fold to halofantrine (7.9 nM (7.3–8.6) vs. 30.4 nM (25.9–34.9); F = 159.3, p < 0.0001), and 11.7-fold to amodiaquine (11.3 nM (10.6–12.1) vs. 132.4 nM (5.5–149.3); F = 243.7, p < 0.0001); similarly, the DD ART-RDD80 strain increased its IC50 2.1-fold to quinine (F = 98.9, p < 0.0001) and 4.5-fold to amodiaquine (F = 152.5, p < 0.0001). Sensitivities to chloroquine (50.1 nM (46.5–53.7) vs. 53 nM (42.7–68.3); F = 0.39, p = 0.54), mefloquine (41.7 nM (39.1–44.4) vs. 39.1 nM (34.1–44.5); F = 0.82, p = 0.37), lumefantrine (7.5 nM (6.3–8.7) vs. 7.8 nM (6.2–9.8); F = 0.13, p = 0.72), and pyrimethamine (16.2 nM (13.8–18.8) vs. 19.9 nM (16.5–24.6); F = 4.75, p = 0.05) remained unchanged (Fig. 6 and Additional file 10).

Fig. 6.

In vitro drug sensitivity profile of the ART-R240 strain. In vitro dose–response curves, with 95% CI error bands, of the ART-R240 strain (red) to (a) dihydroartemisinin (DHA), (b) amodiaquine, (c) mefloquine, (d) chloroquine, (e) quinine, (f) halofantrine, (g) lumefantrine, and (h) pyrimethamine are shown and compared to the sensitive progenitor strain (ART-S) used as a control in each experiment (black). Results were reproducible in several independent experiments. Mean IC50 values (nM) are indicated in parentheses. The probability (p) of these IC50 values being from curves measured using the same strain of parasite, as determined by the extra sum-of-squares F test, are shown for each drug

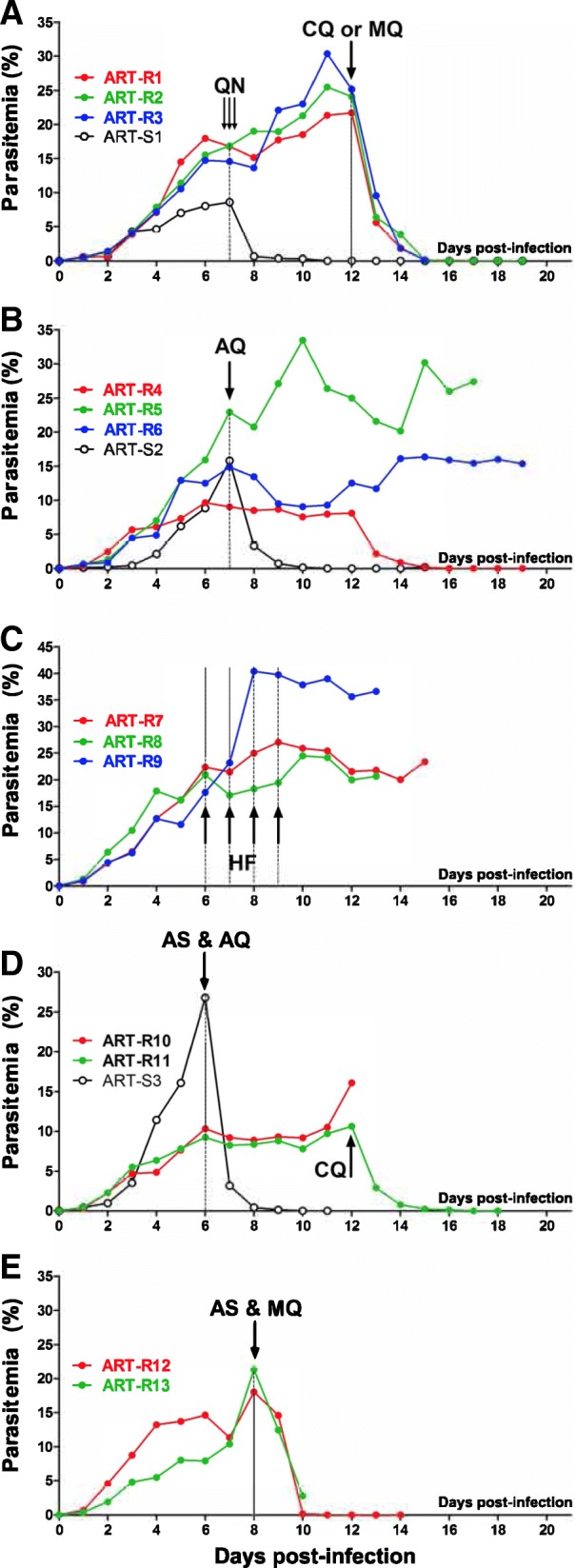

Since the model accommodates simultaneous in vitro and in vivo studies with P. falciparum, this pattern of in vitro co-resistance to main-stream anti-malarial drugs could also be analyzed in vivo (Fig. 7). Therapeutic doses of 219 mg/kg quinine did not induce any decrease in parasitemia in vivo using ART-R240 strain (n = 4, mean ± SD percentage drop in parasitemia 4.8% ± 6.8%); the same dose was effective for the sensitive strain (n = 2, mean ± SD percentage drop in parasitemia 92.2% ± 0.01%; p = 0.03). In addition, we confirmed in vivo resistance to amodiaquine in 4 mice (mean ± SD percentage drop in parasitemia sensitive control 76.6% ± 5.2% vs. ART-R240 9.3% ± 0.14%; p = 0.03), and halofantrine in 3 mice (median, range percentage increase in parasitemia after 3 days of treatment 16.9%, 15.9–114.4%). Conversely, we observed in vivo susceptibility to treatment with mefloquine (2 mice, mean ± SD percentage drop in parasitemia 67.5% ± 7.8%; p = 0.005, compared to normal day-to-day fluctuation) and chloroquine (3 mice, mean ± SD percentage drop in parasitemia 73.3% ± 0.7%; p < 0.001, compared to normal day-to-day fluctuations).

Fig. 7.

In vivo co-resistance of ART-R240 parasites to quinine, amodiaquine, and halofantrine. The ART-R240 strain, which had shown various patterns of co-resistance to other anti-malarials in vitro, was assessed in vivo with the same compounds either alone or in combination with artesunate. a The ART-R240 parasites showed full in vivo resistance to quinine (QN) 219 mg/kg (three doses of 73 mg/kg every 8 h IV). However, the same parasites in the same mice were sensitive to either chloroquine (CQ) (73 mg/kg PO) or mefloquine (MQ) (50 mg/kg i.p.). b, c In vivo resistance to amodiaquine (AQ) (73 mg/kg PO) and halofantrine (HF) (1 mg/kg IV per day, 4 consecutive days) confirmed in vitro indications. d As expected, resistance was seen to a combination of artesunate (AS) and amodiaquine (AQ), whereas parasites in the same animal remained susceptible to chloroquine. e Susceptibility to the artesunate-mefloquine combination was seen in keeping with in vitro results

We also addressed the in vivo response of ART-R240 to two critical combinations in clinical use: AS plus amodiaquine was ineffective (mean ± SD percentage drop in parasitemia 13.1% ± 0.14% vs. 76.5% in the sensitive control), while AS plus mefloquine was effective (mean ± SD percentage drop in parasitemia 66.8% ± 33.6%; p = 0.004, compared to normal day-to-day fluctuations) (Fig. 7d, e).

Thus, in vivo findings mirrored the in vitro sensitivity profiles.

Molecular markers

Restriction fragment length polymorphism assessment of two putative polymorphisms, V3275F and V3306F, in the P. falciparum orthologue of the ubp1 gene revealed no such mutation in the ART-R240, ART-RDD38.4, or parent PAM strain.

Genetic sequencing of PF3D7_1343400 (RAD5 homolog) encoding a putative DNA-repair protein identified the non-synonymous a3392t SNP (MAL13–1718319) in all of the ART-R P. falciparum samples recovered from experimental mice, wherein they had shown resistance to single doses of 38.4 mg/kg, 120 mg/kg, and 240 mg/kg AS, and to a 2-day regimen of 80 mg/kg/day AS. This RAD5 mutation was not identified in the wild type progenitor PAM strain prior to undergoing ART exposure (PAMwt), nor in any of four control clinical P. falciparum isolates collected from Brazil, Senegal, Comoro Islands, and Thailand in the late 1990s. We did not identify any mutation of cNBP in the PAMwt control or ART-R parasites (Additional file 11).

Sequencing of the putative Kelch-13 propeller domain in PF3D7_1343700 (kelch-13) showed no difference between control (3D7, PAMwt) and ART-R strains; it revealed none of the 20 non-synonymous SNPs that have been reported from clinical isolates, nor the SNP identified in P. falciparum that evolved in vitro ART tolerance (M476I) after being cultured for 5 years under artemisinin pressure [45] (Additional file 11). None of the other non-synonymous SNPs in RPB9, PK7, FP2a, or Pfg27 reported in association with the in vitro ART tolerance seen in that strain were found either [45]. Sequencing of exon two of PfCRT revealed the rare CVIKT haplotype [50] linked to moderate resistance to chloroquine in agreement with the in vitro response (chloroquine IC50 = 53 nM).

Pfmdr1 analysis showed a duplication of gene copy number from 1 to 2 copies, and acquisition of the N86Y mutation after in vivo artemisinin drug pressure. No sequence changes were found in the 611 bp PfNHE fragment gene, flanking the DNNND repeat, which is related to quinine resistance [51].

Discussion

Our results indicate that the P. falciparum human malaria parasite can evolve levels of resistance to ART that are much higher than the DPCT phenotype currently observed, and which could carry much graver consequences both for individual patients and global public health. The mechanisms of this stronger resistance are likely distinct from those underlying DPCT.

Progressive drug pressure in this model selected for high-level, stable resistance to ART in vivo rapidly and reproducibly. Parasites were characterized both in vivo and in vitro, yielding convergent data. The most concerning findings are (1) the degree of resistance selected for and (2) co-resistance to quinine, the only alternative for severe malaria. These results justify concerns about the potential of ART-R strengthening to insurmountable levels in patients, particularly if alternative treatments do not make it through the development pipeline fast enough to offset the prevailing ART drug pressure.

The Pf-NSG model – borne out of our malaria vaccine development project [31, 32] – includes a number of key features that facilitated the selection of ART-R P. falciparum. Mice had parasite biomasses ranging from 2.5 × 109 to 3.8 × 109 per mouse, which is in the range seen in an uncomplicated human infection [52]. These parasites were exposed to AS and its bio-active metabolites (primarily DHA) under similar pharmacokinetics to human infection through metabolic factors that cannot be accounted for in vitro. Drug disposition in these mice (DHA t½ of 36 min) is comparable to patients with malaria [53, 54]. While our drug administration protocol was designed to hasten the evolution of ART-R in vivo with single doses, it is not unrealistic to expect ART mono-therapy [55], poor treatment compliance [56, 57], and counterfeit products [58–60] to lead to similarly sub-therapeutic, resistance-selective dosing schedules in the field.

Notable differences between this model and human malaria are that both sexual recombination of parasite genes in the vector and effects of host immunity are by-passed through direct sub-inoculation between mice devoid of an adaptive immune system.

The model allowed us to exert progressive AS pressure, rapidly selecting for ART-R and to characterize resistant strains by their pattern of response to a range of antimalarial drugs in vivo and in vitro. Two stages could be distinguished during the evolution of ART-R. First, parasites showed substantial resistance to AS in vivo (up to absence of response to a single dose 30 mg/kg, i.e., 400-fold decrease in sensitivity) without an associated shift in IC50. This discrepancy between early in vivo resistance and conventional in vitro assays fits with the DPCT pattern seen in humans [6, 7, 61–63], supporting the relevance of this model. It confirms that IC50 is not a reliable marker of ART-R.

The phenotype of the second stage of ART-R in this model is in stark contrast to the clinical manifestations of DPCT. This extreme phenotype is clearly different as (1) there is a complete absence of response to very high doses of intravenous AS (240 mg/kg, i.e., 3200-fold decrease in sensitivity), (2) a major shift in DHA-IC50 was demonstrated, and (3) the parasites demonstrated full co-resistance to quinine. The second stage was further characterized as having reproducible stability.

Only two clinical cases of ART-R with increased DHA IC50 (14.0 nM and 14.4 nM) have been reported [62]; the absolute increase of DHA IC50 that we observed (99.9 nM) is far greater, confirming that it differs substantially from DPCT. We can expect that measuring conventional IC50 in the field will continue to fail to unmask in vivo ART-R, even if resistance strengthens to considerably higher levels. The novel RSA could provide a more sensitive means for detecting the early emergence of ART-R, although it is technically challenging [29, 30]. As IC50 did increase in our model, in contrast to the more moderately resistant parasites in the field, the need to perform RSA was less evident, although this could be of interest.

Not only is the degree of resistance achieved alarming, but also the ease with which ART-R selection occurred, specifically 80% of attempts with single-dose and 41% with 2-day treatments. The 2-day regimen was less efficient at inducing ART-R, the shift in IC50 was lower, and co-resistance was less pronounced. This suggests that measures, such as intensified schedules, higher doses and improved compliance with anti-malarial therapy may retard the advancement of ART-R but, ultimately, are unlikely to be sufficient.

The most burning question that remains is, what point along the road to stable, high-level ART-R, as seen in this model, are we currently witnessing in humans? AS is administered at 4 mg/kg/day for uncomplicated malaria as part of a 3-day ACT course. In areas where ART-R has emerged in humans, the percentage parasite reduction rate after 24 h in patient’s blood after drug treatment has decreased only modestly, from 99% to 85–91% [64]. We selected for a strain that showed no significant drop in parasitemia at 24 h (i.e., percentage parasite reduction rate after 24 h, 0–27%) after exposure to the human dose of 4 mg/kg AS. This full-resistance phenotype was maintained throughout a step-wise strengthening of the dose up to 240 mg/kg AS, leaving a frightening margin for increase in resistance in the field. Thus, if wild parasites evolve along the same trajectory as observed in our P. falciparum experimental model, we are currently only seeing the tip of the iceberg in the clinic. The absence of adaptive immunity and reduced innate immunity in these mice makes it difficult to extrapolate our findings to human hosts, particularly the speed at which similar resistance may arise.

In the search for a molecular surveillance marker, genetic studies of well-defined clinical isolates from Southeast Asia have demonstrated an association between the DPCT phenotype and non-synonymous mutations of the propeller region in kelch-13 [10, 11, 45, 46, 65, 66] and, to a lesser extent, an SNP in RAD5, which ranked first in one GWAS [44] and fourth in a meta-analysis of relevant GWAS [46]. In a recent GWAS from the China-Myanmar border, RAD5 was significantly associated with ART-R, while kelch-13 was not flagged at all [24]. In our highly ART-R strains we found no kelch-13 mutation; conversely, we found selection of the exact same RAD5 SNP identified in clinical samples [44, 46]. A limitation is that we refrained from performing whole genome sequencing, which would likely reveal numerous mutations, the roles of which would require lengthy investigation and could be the focus of future studies.

The significance of the many kelch-13 mutations is not as straightforward as was once thought [67]. In the original Southeast Asia focus of ART-R, approximately 30 different SNPs have been found in kelch-13, circa 20 of which are in the paddle region. Mutations in this region have been confirmed by four distinct GWAS to be significantly associated with DPCT in Southeast Asian parasites [26, 44, 46, 68]. However, a substantial number of isolates with the same mutations (in the locations with high DPCT prevalence) showed no sign of delayed clearance and, perhaps more importantly, a number of isolates with the wild type genotype showed DPCT [10, 45]. Data from Africa are even more puzzling – in the absence of any clear DPCT phenotype, an unexpectedly large number of kelch-13 propeller SNPs were found in parasites from 14 African sites, some at high frequency; 15 of these 24 SNPs were novel, but 3 have previously been associated with DPCT in Southeast Asia [69]. Thus, we are now faced with a number of kelch-13 mutant alleles of uncertain clinical significance. On the other hand, SNPs in RAD5 are extremely rare outside Asia [70], yet one was selected for in our parasites of African origin under ART pressure.

Our results add a further layer of complexity, showing that far stronger ART-R can exist in P. falciparum without kelch-13 propeller domain mutations, implying that other ART-R genes or mechanisms exist and will need to be characterized. The two strains and the novel in vivo model we developed provide the tools to do so. In practical terms, ART-R should no longer be considered excluded just because there is an absence of kelch-13 mutations. This has important consequences for ART-R surveillance in Africa.

Our results are in keeping with a recent study that relates ART-R to an interaction of dihydroartemisinin with phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate kinase, and indicates that elevated phosphatidyl-inositol-3 phosphate can be associated with resistance in the absence of kelch-13 mutations [71]. kelch-13 is not a direct target of ART [27, 28]. Indirect effects of kelch-13 mutations on phosphatidyl-inositol-3 phosphate and glutathione may counteract ART [28], but it is unlikely to be the only player. Whatever the mechanism, the suggestion that far stronger resistance might yet evolve stealthily in humans calls for urgent and radical measures to monitor and contain ART-R.

We did not run a control group in parallel. During our experience with P. falciparum in successive mouse models [32], using both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant parasites [41], and more recently in the NSG model [31], we never observed a spontaneous change in drug response. These models were developed for our vaccine development project; the many animals infected by P. falciparum either contributed to understanding innate defense against malaria [31, 72] or were passively immunized to screen vaccine candidates [32, 73]. In this context, the parasite employed for the present study had already been passaged in mice for 7 months and proved to have maintained sensitivity to ART derivatives and other drugs both in vivo (Figs. 1 and 7) and in vitro (Figs. 5 and 6), where it served as the sensitive reference. However, a control parasite line should have been maintained in mice, in parallel, without drug exposure – this is a limitation of the study.

We repeatedly find ourselves on the back-foot in the campaign against malaria as there is a lack of tools to help us anticipate how the parasite will adapt to policy changes. GWAS, which have been extensively used, have major limitations. They can only characterize resistant parasites after they have emerged and merely provide circumstantial, rather than causative, evidence. One practical suggestion could be the application of novel models, such as the one presented here, to study the evolution and analyze the phenotypic adaptation of malaria parasites to drug pressure in vivo. While clinical efficacy data should remain the gold standard, the model presented here could be used as a tool to assess the phenotype of isolates with given genotypes (e.g., novel kelch-13 mutations identified in Africa). Patient isolates can readily grow in the Pf-NSG model [31], allowing in vitro and in vivo methods to be used concurrently on clinical isolates. The model may also be used to characterize in vivo responses to experimental molecules at a preclinical level, and to trial alternative drug combinations (including triple therapy) that might bridle the evolution of ART-R [3]. This will allow an estimation of the time to resistance evolution for each compound or combination, without the impractical delays seen using in vitro methods [23].

The concomitant development of full resistance to quinine, halofantrine, and amodiaquine in the ART-R240 strain, despite exclusive exposure to AS, was unforeseen. However, it is not all too surprising as in vitro resistance to quinine has previously been reported after exclusive exposure to ART [74]. Resistance to structurally unrelated antimalarials has been linked to changes in the Pfmdr1 gene, which encodes the P-glycoprotein pump essential for parasite detoxification [75]. In this study, the ART-R120 strain and ART-R240 had an amplified pfmdr gene, in agreement with the high level of resistance developed towards AS, quinine, halofantrine, and amodiaquine [48]. An association of AS-mefloquine treatment failure with increased pfmdr copy number has been reported in north-western Cambodia [76].

The phenomenon of multidrug resistance despite single drug exposure is well recognized in microbiology and, in some instances, is mediated by up-regulation of a pro-mutagenic DNA repair response [77]. Parasites from Cambodia have a pro-mutagenic phenotype, favoring acquisition of new mutations [78]. Intense oxidative stress caused by AS exposure could stimulate this process [79]. It remains to be seen if the mutation in RAD5, a gene encoding a DNA post-replication repair protein [80], contributes to a pro-mutagenic state and development of multidrug resistance, or if it improves DNA repair.

Co-resistance to IV quinine and to one of the most widely used ACTs (AS-amodiaquine) – two critical weapons in the anti-malaria armamentarium – was fully verified both in vivo and in vitro. Resistance to quinine also arose using the DD regimen, indicating it has unlikely occurred by chance. Though high quinine IC50 values have occasionally been reported ex vivo (e.g., 829 nM and 1019 nM) [29, 41], to our knowledge, frank resistance to treatment with a 219 mg/kg dose, as seen here, has not been reported from the clinic. Given the widespread use of ACT worldwide, the suggestion that ART pressure might also favor quinine resistance is of major concern.

Conclusion

These results were obtained in vivo using P. falciparum maintained in huRBC. Should clinical resistance to ART and ACT evolve further along the trajectory seen here, with co-resistance to quinine and other antimalarials, we would be left abruptly with no satisfactory option for treating severe malaria and a compromised choice of treatments for uncomplicated malaria [3]. Indeed, the current dependence on ARTs for both uncomplicated and severe malaria, together with a lack of viable therapeutic alternatives, leaves decision-makers with very limited options. This would have dire consequences not only in the management of individual cases, but would cripple efforts to achieve malaria control globally.

Additional files

Details of genes, regions and primers used in genetic sequencing of P. falciparum artemisinin-resistant and control strains. (PDF 83 kb)

Morphological changes of artemisinin-resistant parasites under treatment. (PDF 181 kb)

Selection schema for single-dose resistant strain. (PDF 160 kb)

Schematic representation of use of drug pressure to select for single-dose resistance in one mouse. (PDF 204 kb)

Number and intensity of artesunate drug pressure cycles required to select for artemisinin resistance using single doses of artesunate. (PDF 97 kb)

Gametocytes developing from artemisinin resistant parasites. (PDF 108 kb)

Selection schema for 2-day dose resistant strain. (PDF 140 kb)

Number and intensity of artesunate drug pressure cycles required to select for artemisinin resistance using a 2-day artesunate regimen. (PDF 93 kb)

Mouse plasma dihydroartemisinin (DHA) concentrations measured after intravenous administration of artesunate. (PDF 108 kb)

In vitro IC50 (95% CI) values at different stages of artemisinin resistance (ART-R). (PDF 69 kb)

Genetic sequencing of RAD5, cNBP, and K-13. (PDF 1419 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the financial contributions received from the Vac4All Initiative. We are indebted to Nicolas Widmer for performing pharmacokinetic calculations. We thank Christian Roussilhon, Geneviève Milon, Karima Brahimi, and Edgar Badell for their advice and contributions. We are grateful to Dr. Nico van Rooijen, Antion Longo (Sigma-Tau), and Philippe Brasseur for their generous gifts of essential materials.

Funding

This work was funded by the Vac4All Initiative. The initial mouse model employed was developed by the Bio-Medical Parasitology Unit at Institut Pasteur. Vac4all thereafter covered the expenses of personnel, reagents, animals, molecular studies, rent, and sundries required to gather the results presented.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. The resistant strains are available on request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ACT

artemisinin-based combination therapy

- APC

artesunate pressure cycle

- ART

artemisinin

- ART-R

artemisinin resistance of any level

- AS

artesunate

- CI

confidence interval

- DD

double dose

- DHA

dihydroartemisinin

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DPCT

delayed parasite clearance time

- GWAS

genome wide association study

- huRBC

human erythrocytes

- IC50

50% inhibitory concentration

- LED

lowest effective dose

- NSG

NOD/SCID IL-2Rγ−/− mice

- PAM

Uganda Palo Alto Marburg strain of P. falciparum

- RSA

ring-stage survival

- SD

standard deviation

Authors’ contributions

RKT performed in vivo and in vitro experiments. PJG performed in vitro experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to writing manuscript. LA performed in vivo experiments and designed methods. LD determined plasma DHA concentrations. RT performed molecular studies. EP performed molecular studies. JLP and PO analyzed data and contributed to writing the manuscript. PD designed experiments, analyzed results, and supervised writing manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were carried out in line with European Community Council Directive, 24th November 1986 (86/609/EEC), and European Union guidelines. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Pasteur Institute Animal ethical committee (approval number A 75 15–27).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Organisation WH . 2nd edition: World Health Organisation; 2010. 2011. Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria. [Google Scholar]

- 2.White NJ. Qinghaosu (artemisinin): the price of success. Science. 2008;320(5874):330–334. doi: 10.1126/science.1155165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phyo AP, von Seidlein L. Challenges to replace ACT as first-line drug. Malar J. 2017;16(1):296. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1942-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dondorp AM, Yeung S, White L, Nguon C, Day NP, Socheat D, von Seidlein L. Artemisinin resistance: current status and scenarios for containment. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(4):272–280. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phyo AP, Nkhoma S, Stepniewska K, Ashley EA, Nair S. McGready R, ler Moo C, Al-Saai S, Dondorp AM, Lwin KM et al: Emergence of artemisinin-resistant malaria on the western border of Thailand: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2012;379(9830):1960–1966. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60484-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Lwin KM, Ariey F, Hanpithakpong W, Lee SJ, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, Smith BL, Socheat D, Fukuda MM. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(24):2619–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hien TT, Thuy-Nhien NT, Phu NH, Boni MF, Thanh NV, Nha-Ca NT. Thai le H, Thai CQ, Toi PV, Thuan PD et al: In vivo susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to artesunate in Binh Phuoc Province, Vietnam. Malar J. 2012;11:355. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyaw MP, Nyunt MH, Chit K, Aye MM, Aye KH, Aye MM, Lindegardh N, Tarning J, Imwong M, Jacob CG, et al. Reduced susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to artesunate in southern Myanmar. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, Anderson JM, Mao S, Sam B, et al. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(5):411–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menard D, Khim N, Beghain J, Adegnika AA, Shafiul-Alam M, Amodu O, Rahim-Awab G, Barnadas C, Berry A, Boum Y, et al. A Worldwide Map of Plasmodium falciparum K13-Propeller Polymorphisms. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(25):2453–2464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkes M, Conroy AL, Kain KC. Spread of artemisinin resistance in malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1944–1945. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1410735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beshir KB, Sutherland CJ, Sawa P, Drakeley CJ, Okell L, Mweresa CK, Omar SA, Shekalaghe SA, Kaur H, Ndaro A, et al. Residual Plasmodium falciparum parasitemia in Kenyan children after artemisinin-combination therapy is associated with increased transmission to mosquitoes and parasite recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(12):2017–2024. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dondorp AM, Fairhurst RM, Slutsker L, Macarthur JR, Breman JG, Guerin PJ, Wellems TE, Ringwald P, Newman RD, Plowe CV. The threat of artemisinin-resistant malaria. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1073–1075. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1108322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dell'Acqua R, Fabrizio C, Di Gennaro F, Lo Caputo S, Saracino A, Menegon M, L'Episcopia M, Severini C, Monno L, Castelli F, et al. An intricate case of multidrug resistant Plasmodium falciparum isolate imported from Cambodia. Malar J. 2017;16(1):149. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1795-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imwong M, Hien TT, Thuy-Nhien NT, Dondorp AM, White NJ. Spread of a single multidrug resistant malaria parasite lineage (PfPailin) to Vietnam. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(10):1022–1023. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwansa-Bentum B, Ayi I, Suzuki T, Otchere J, Kumagai T, Anyan WK, Osei JH, Asahi H, Ofori MF, Akao N, et al. Plasmodium falciparum isolates from southern Ghana exhibit polymorphisms in the SERCA-type PfATPase6 though sensitive to artesunate in vitro. Malar J. 2011;10:187. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phompradit P, Wisedpanichkij R, Muhamad P, Chaijaroenkul W, Na-Bangchang K. Molecular analysis of pfatp6 and pfmdr1 polymorphisms and their association with in vitro sensitivity in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the Thai-Myanmar border. Acta Trop. 2011;120(1-2):130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pillai DR, Lau R, Khairnar K, Lepore R, Via A, Staines HM, Krishna S. Artemether resistance in vitro is linked to mutations in PfATP6 that also interact with mutations in PfMDR1 in travellers returning with Plasmodium falciparum infections. Malar J. 2012;11:131. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jambou R, Legrand E, Niang M, Khim N, Lim P, Volney B, Ekala MT, Bouchier C, Esterre P, Fandeur T, et al. Resistance of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates to in-vitro artemether and point mutations of the SERCA-type PfATPase6. Lancet. 2005;366(9501):1960–1963. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afonso A, Hunt P, Cheesman S, Alves AC. Cunha CV, do Rosario V, Cravo P: Malaria parasites can develop stable resistance to artemisinin but lack mutations in candidate genes atp6 (encoding the sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase), tctp, mdr1, and cg10. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(2):480–489. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.480-489.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puri SK, Chandra R. Plasmodium vinckei: selection of a strain exhibiting stable resistance to arteether. Exp Parasitol. 2006;114(2):129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witkowski B, Lelievre J, Barragan MJ, Laurent V, Su XZ, Berry A, Benoit-Vical F. Increased tolerance to artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum is mediated by a quiescence mechanism. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(5):1872–1877. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01636-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Cabrera M, Yang J, Yuan L, Gupta B, Liang X, Kemirembe K, Shrestha S, Brashear A, Li X, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies genetic loci associated with resistance to multiple antimalarials in Plasmodium falciparum from China-Myanmar border. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33891. doi: 10.1038/srep33891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mok S, Ashley EA, Ferreira PE, Zhu L, Lin Z, Yeo T, Chotivanich K, Imwong M, Pukrittayakamee S, Dhorda M, et al. Population transcriptomics of human malaria parasites reveals the mechanism of artemisinin resistance. Science. 2014;47(6220):431–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1260403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheeseman IH, Miller BA, Nair S, Nkhoma S, Tan A, Tan JC, Al Saai S, Phyo AP, Moo CL, Lwin KM, et al. A major genome region underlying artemisinin resistance in malaria. Science. 2012;336(6077):79–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1215966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Zhang CJ, Chia WN, Loh CC, Li Z, Lee YM, He Y, Yuan LX, Lim TK, Liu M, et al. Haem-activated promiscuous targeting of artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10111. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siddiqui G, Srivastava A, Russell AS, Creek DJ. Multi-omics Based Identification of Specific Biochemical Changes Associated With PfKelch13-Mutant Artemisinin-Resistant Plasmodium falciparum. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(9):1435–1444. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Khim N, Sreng S, Chim P, Kim S, Lim P, Mao S, Sopha C, Sam B, et al. Novel phenotypic assays for the detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: in-vitro and ex-vivo drug-response studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(12):1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70252-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chotivanich K, Tripura R, Das D, Yi P, Day NP, Pukrittayakamee S, Chuor CM, Socheat D, Dondorp AM, White NJ. Laboratory detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(6):3157–3161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01924-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnold L, Tyagi RK, Meija P, Swetman C, Gleeson J, Perignon JL, Druilhe P. Further improvements of the P. falciparum humanized mouse model. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e18045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badell E, Oeuvray C, Moreno A, Soe S, van Rooijen N, Bouzidi A, Druilhe P. Human malaria in immunocompromised mice: an in vivo model to study defense mechanisms against Plasmodium falciparum. J Exp Med. 2000;192(11):1653–1660. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fandeur T, Bonnefoy S, Mercereau-Puijalon O. In vivo and in vitro derived Palo Alto lines of Plasmodium falciparum are genetically unrelated. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;47(2):167–178. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siddiqui WA, Schnell JV, Geiman QM. A model in vitro system to test the susceptibility of human malarial parasites to antimalarial drugs. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1972;21(4):393–399. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1972.21.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Lucia S, Tsamesidis I, Pau MC, Kesely KR, Pantaleo A, Turrini F. Induction of high tolerance to artemisinin by sub-lethal administration: A new in vitro model of P. falciparum. PloS One. 2018;13(1):e0191084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe AW, Eyster E, Kellner A. Liquid nitrogen preservation of red blood cells for transfusion; a low glycerol-rapid freeze procedure. Cryobiology. 1968;5(2):119–128. doi: 10.1016/S0011-2240(68)80154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lambros C, Vanderberg JP. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J Parasitol. 1979;65(3):418–420. doi: 10.2307/3280287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reese RT, Langreth SG, Trager W. Isolation of stages of the human parasite Plasmodium falciparum from culture and from animal blood. Bull World Health Organ. 1979;57(Suppl 1):53–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Druilhe P, Moreno A, Blanc C, Brasseur PH, Jacquier P. A colorimetric in vitro drug sensitivity assay for Plasmodium falciparum based on a highly sensitive double-site lactate dehydrogenase antigen-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2001;64(5-6):233–241. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Desjardins RE, Canfield CJ, Haynes JD, Chulay JD. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16(6):710–718. doi: 10.1128/AAC.16.6.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moreno A, Badell E, Van Rooijen N, Druilhe P. Human malaria in immunocompromised mice: new in vivo model for chemotherapy studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(6):1847–1853. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.6.1847-1853.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodel EM, Zanolari B, Mercier T, Biollaz J, Keiser J, Olliaro P, Genton B, Decosterd LA. A single LC-tandem mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous determination of 14 antimalarial drugs and their metabolites in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877(10):867–886. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunt P, Afonso A, Creasey A, Culleton R, Sidhu AB, Logan J, Valderramos SG, McNae I. Cheesman S, do Rosario V et al: Gene encoding a deubiquitinating enzyme is mutated in artesunate- and chloroquine-resistant rodent malaria parasites. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65(1):27–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takala-Harrison S, Clark TG, Jacob CG, Cummings MP, Miotto O, Dondorp AM, Fukuda MM, Nosten F, Noedl H, Imwong M, et al. Genetic loci associated with delayed clearance of Plasmodium falciparum following artemisinin treatment in Southeast Asia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(1):240–245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211205110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, Kim S, Duru V, Bouchier C, Ma L, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505(7481):50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takala-Harrison S, Jacob CG, Arze C, Cummings MP, Silva JC, Dondorp AM, Fukuda MM, Hien TT, Mayxay M, Noedl H, et al. Independent emergence of artemisinin resistance mutations among Plasmodium falciparum in Southeast Asia. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(5):670–679. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Basco LK, Ringwald P. Molecular epidemiology of malaria in Yaounde, Cameroon. III. Analysis of chloroquine resistance and point mutations in the multidrug resistance 1 (pfmdr 1) gene of Plasmodium falciparum. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1998;59(4):577–581. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Price RN, Uhlemann AC, Brockman A, McGready R, Ashley E, Phaipun L, Patel R, Laing K, Looareesuwan S, White NJ, et al. Mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and increased pfmdr1 gene copy number. Lancet. 2004;364(9432):438–447. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16767-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nontprasert A, Pukrittayakamee S, Nosten-Bertrand M, Vanijanonta S, White NJ. Studies of the neurotoxicity of oral artemisinin derivatives in mice. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2000;62(3):409–412. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagesha HS, Casey GJ, Rieckmann KH, Fryauff DJ, Laksana BS, Reeder JC, Maguire JD, Baird JK. New haplotypes of the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (pfcrt) gene among chloroquine-resistant parasite isolates. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2003;68(4):398–402. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menard D, Andriantsoanirina V, Khim N, Ratsimbasoa A, Witkowski B, Benedet C, Canier L, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Durand R. Global analysis of Plasmodium falciparum Na(+)/H(+) exchanger (pfnhe-1) allele polymorphism and its usefulness as a marker of in vitro resistance to quinine. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2013;3:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White NJ, Pongtavornpinyo W, Maude RJ, Saralamba S, Aguas R, Stepniewska K, Lee SJ, Dondorp AM, White LJ, Day NP. Hyperparasitaemia and low dosing are an important source of anti-malarial drug resistance. Malar J. 2009;8:253. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melendez V. Metabolic profile of artesunate and DHA using human plasma, liver, and hepatocytes. In: Annual progress report. Pennsylvania. USA: Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences; 2003. p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davis TM, Phuong HL, Ilett KF, Hung NC, Batty KT, Phuong VD, Powell SM, Thien HV, Binh TQ. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous artesunate in severe falciparum malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(1):181–186. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.181-186.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeung S, Van Damme W, Socheat D, White NJ, Mills A. Access to artemisinin combination therapy for malaria in remote areas of Cambodia. Malar J. 2008;7:96. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen JL, Yavuz E, Morris A, Arkedis J, Sabot O. Do patients adhere to over-the-counter artemisinin combination therapy for malaria? evidence from an intervention study in Uganda. Malar J. 2012;11:83. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lemma H, Lofgren C, San Sebastian M. Adherence to a six-dose regimen of artemether-lumefantrine among uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum patients in the Tigray Region, Ethiopia. Malar J. 2011;10:349. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Newton PN, McGready R, Fernandez F, Green MD, Sunjio M, Bruneton C, Phanouvong S, Millet P, Whitty CJ, Talisuna AO, et al. Manslaughter by fake artesunate in Asia--will Africa be next? PLoS Med. 2006;3(6):e197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sengaloundeth S, Green MD, Fernandez FM, Manolin O, Phommavong K, Insixiengmay V, Hampton CY, Nyadong L, Mildenhall DC, Hostetler D, et al. A stratified random survey of the proportion of poor quality oral artesunate sold at medicine outlets in the Lao PDR - implications for therapeutic failure and drug resistance. Malar J. 2009;8:172. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.El-Duah M, Ofori-Kwakye K. Substandard artemisinin-based antimalarial medicines in licensed retail pharmaceutical outlets in Ghana. Journal of vector borne diseases. 2012;49(3):131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amaratunga C, Sreng S, Suon S, Phelps ES, Stepniewska K, Lim P, Zhou C, Mao S, Anderson JM, Lindegardh N, et al. Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Pursat province, western Cambodia: a parasite clearance rate study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(11):851–858. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70181-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Noedl H, Se Y, Sriwichai S, Schaecher K, Teja-Isavadharm P, Smith B, Rutvisuttinunt W, Bethell D, Surasri S, Fukuda MM, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Cambodia: a clinical trial designed to address an emerging problem in Southeast Asia. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;51(11):e82–e89. doi: 10.1086/657120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leang R, Barrette A, Bouth DM, Menard D, Abdur R, Duong S, Ringwald P. Efficacy of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in Cambodia, 2008 to 2010. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(2):818–826. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00686-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Das D, Tripura R, Phyo AP, Lwin KM, Tarning J, Lee SJ, Hanpithakpong W, Stepniewska K, Menard D, Ringwald P, et al. Effect of high-dose or split-dose artesunate on parasite clearance in artemisinin-resistant falciparum malaria. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;56(5):e48–e58. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]