Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to estimate the efficacy of elagolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist, for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain.

Methods

This was a phase II, randomized, placebo-controlled parallel group study conducted at 37 US centers, consisting of an 8-week double-blind period followed by a 16-week open-label period. Patients were 137 women aged 18 to 49, with laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis and moderate to severe nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea, who were administered elagolix 150 mg daily or placebo. The primary outcomes of the study were the daily assessment of dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia using a modified Biberoglu-Behrman scale.

Results

During the double-blind period, there were significantly greater mean reductions from baseline to week 8 in dysmenorrhea (-1.13 ± 0.11 vs. −0.37 ± 0.11, p<0.0001), nonmenstrual pelvic pain (-0.47 ± 0.07 vs. −0.19 ± 0.07, p = 0.0066), and dyspareunia scores (-0.61 ± 0.10 vs. −0.23 ± 0.10, p = 0.0070) in the elagolix group compared with placebo. Continued improvements were observed during the open-label treatment regardless of initial treatment allocation. Elagolix treatment was also associated with significant improvements in quality-of-life measures during the double-blind and open-label periods. The most common adverse events occurring with elagolix were nausea, headache and hot flush, each in 9.9% of patients.

Conclusion

Elagolix effectively reduced endometriosis-associated pelvic pain over a 24-week period and was well-tolerated.

Keywords: Elagolix, Endometriosis, GnRH antagonists, Pelvic pain

Introduction

Endometriosis is a prevalent disease estimated to affect 10% of women of reproductive age, up to 50% of women with pelvic pain, and 20%-50% of women with reduced fertility (1). The most common symptom is pelvic pain, which presents as dysmenorrhea in over 98% of patients with symptomatic endometriosis and also nonmenstrual pelvic pain. Pelvic pain associated with endometriosis varies greatly in intensity, frequency and duration from patient to patient. Nonmenstrual pelvic pain is usually chronic (lasting >6 months), and it can be intermittent throughout the menstrual cycle or continuous and may present as dull, throbbing, or sharp pain (2, 3). In addition, the pain related to endometriosis has been shown to impair both work-related and non-work-related daily activities (4-6).

Current treatment options for the management of pain associated with endometriosis include medical therapies and surgical interventions, most frequently laparoscopic excision of endometriotic lesions. Oral contraceptives are frequently used as first-line therapy for endometriosis-associated pain. In the case of patients who do not have consistent symptom improvements with oral contraceptives, or when oral contraceptives are contraindicated for safety reasons, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists are often considered. In addition, endometriosis is a chronic, progressive disease, and as a result many patients will eventually require second-line therapy, including treatment with GnRH agonists. GnRH agonists are effective in reducing pelvic pain, even in patients who have become unresponsive to other treatments, but are associated with significant hypoestrogenic side effects, including unacceptable bone loss, which limit their long-term use (7, 8). Hormonal add-back therapy reduces bone loss and vasomotor symptoms (9), but is prescribed in only one third of women taking GnRH agonists (10).

Elagolix sodium is an oral, short-acting, nonpeptide, GnRH antagonist that has been demonstrated to suppress ovarian estrogen production in a dose-dependent manner (11, 12). Daily administration of oral doses of placebo or elagolix 50 mg or 150 mg in healthy women for 42 days was associated with median estradiol values of 120 pg/mL, 53 pg/mL and 30 pg/mL, respectively (data on file). These phase I data were informative for dose selection in subsequent phase II studies.

Phase II studies in women with endometriosis, including a 6-month, active comparator study (using leuprolide acetate), which evaluated the effects of various doses of elagolix on bone mineral density (BMD) and estradiol levels in women with endometriosis (13) have been conducted. These studies demonstrated that elagolix 150 mg reduces endometriosis-associated pain, partially suppresses estradiol and results in minimal changes in BMD. Notably, the 6-month active comparator trial utilized a monthly composite scale to assess signs and symptoms of endometriosis, similar to studies with previously approved medications for the treatment of endometriosis (14, 15). These monthly recall scales are known to have a recall bias that may not accurately reflect day-to-day pain variability (16). Similar problems have been reported with weekly recall scales when compared with daily pain diaries (17). Because of these issues and in response to recommendations received from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the traditional Biberoglu-Behrman scale components of dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia with the 30-day recall period were modified to capture the daily experience of endometriosis-related pain based on focus group interviews and assessed on a daily basis using an electronic diary (e-Diary) in this study. The e-Diary has been partially validated according to the FDA guidelines on patient-reported outcomes (18). The full validation study will be published separately.

This report presents the clinical data from the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with these modified Biberoglu-Behrman pain scales in patients with surgically confirmed endometriosis. The primary objective of the study was to estimate the efficacy of elagolix for reducing dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia using daily pain scales. The duration of the placebo-controlled treatment period (8 weeks) was chosen as the minimum time necessary to assess treatment effect on the primary outcome measure without excessive dropout in the placebo group. The 6-month duration of the overall treatment period reflects the standard in most endometriosis pain trials; patients initially randomized to placebo went on to receive active treatment for the 16-week remainder of the trial.

Materials and Methods

Study design

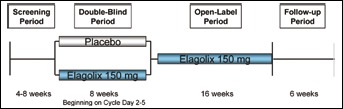

This phase II, randomized, multicenter, parallel group study evaluated the efficacy of elagolix 150 mg administered once daily in the treatment of moderate to severe endometriosis-associated pain at 37 US centers from October 2009 to September 2010, and also explored elagolix's tolerability at this dose. The study consisted of up to 8 weeks of screening with data collection to establish baseline pain, an 8-week double-blind placebo-controlled treatment period, a 16-week open-label treatment period with all patients receiving elagolix 150 mg once per day, and a 6-week posttreatment follow-up period (Fig. 1). The study protocol was approved by a central independent review board (Shulman IRB) or a site's local IRB and was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (19).

Fig. 1.

Study design.

Efficacy measures

The primary efficacy measures included the daily assessment of dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia on a 4-point modified Biberoglu-Behrman scale (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe) using an e-Diary. Additional efficacy measures included daily reporting of analgesic use on an e-Diary. Patients recorded the use of any analgesics, if the analgesic was prescribed or not and, if prescribed, whether the medication was a narcotic (examples of narcotics were provided, and patients were asked to request permission from the study site prior to taking any prescription medications). Monthly means were calculated with a “month” defined as the interval of time between consecutive scheduled clinic visits (approximately 28 days). Monthly assessments of pain symptoms were performed at screening and at treatment weeks 8 and 24 using the composite pelvic signs and symptoms score (CPSSS) with 5 components addressing dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, nonmenstrual pelvic pain, pelvic tenderness and pelvic induration, according to the original 4-point Biberoglu-Behrman scale (20). The total CPSSS was calculated as the sum of the total component scores at a given visit. Additional patient-reported efficacy measures included assessment of quality of life using the Endometriosis Health Profile-5 (EHP-5) (21) core questionnaire, and overall improvement was assessed using the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) on a 7-point scale (1 = very much improved, 2 = much improved, 3 = minimally improved, 4 = not changed, 5 = minimally worse, 6 = much worse, 7 = very much worse).

Safety

The incidence and severity of adverse events were recorded throughout the study. Vital signs and standard clinical laboratory assessments were performed by a central laboratory (ICON Laboratories, Farmingdale, NY, USA). Patients recorded the occurrence and intensity of their uterine bleeding in an e-Diary from screening through the follow-up visit using the following guidelines: light = spotting, moderate = normal flow, heavy = heavy flow with flooding and/or clotting.

Patients

Eligible patients were women aged 18 to 49 years, with a laparoscopically documented diagnosis of endometriosis within 8 years of screening who had moderate to severe endometriosis-related pain during the screening period. This included a total CPSSS >6 at initial screening, at least 14 days of e-Diary entries during screening with at least 1 dysmenorrhea assessment of at least moderate (score >2) and at least 1 nonmenstrual pelvic pain assessment of at least moderate (score >2), and who had moderate or severe dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pelvic pain (assessed using the Baseline Assessment of Dysmenorrhea and Nonmenstrual Pelvic Scale) at baseline. A minimum interval of 1 month was required between surgery and the beginning of screening, to be included in the study. Eligible participants were also required to use 2 forms of nonhormonal contraception (such as condom and spermicide).

Patients were excluded if they were administered a GnRH agonist, a GnRH antagonist other than elagolix, or danazol within 6 months of screening, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate within 3 months of screening, or had used hormonal contraception or other hormonal therapy within 1 month of screening. Women who had chronic pelvic pain that was not caused by endometriosis (as judged by the investigator) were also excluded. In addition, women had to have a history of regular menstrual cycles (28 ± 5 days) within 6 months of screening.

Randomization and blinding

After screening, patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive a daily tablet of elagolix 150 mg or matching placebo, beginning within 2-5 days of their menstrual cycle and continuing for the first 8 weeks of treatment. Patients were randomized using an interactive voice response system (IVRS). A computer-generated randomized treatment schedule was used to assign treatments immediately prior to the first dose of study drug. After 8 weeks, all active patients received open-label elagolix 150 mg treatment for an additional 16 weeks. Patients, the investigator and all study personnel were blinded to the patient's double-blind period treatment assignment throughout the study. Results were unblinded at the group level (i.e., individual patient's treatment allocations were not unblinded) after all patients completed week 8, for an interim efficacy analysis. This analysis was conducted by an independent statistician to estimate the efficacy of elagolix 150 mg for the planning of future efficacy studies.

Use of analgesics

Mild analgesics (e.g., naproxen, celecoxib, ibuprofen, mefenamic acid, and acetaminophen) and strong analgesics (e.g., hydrocodone, acetaminophen and codeine, acetaminophen and hydrocodone, and ketorolac) were permitted on an as-needed basis and were documented by the patients in their e-Diaries. Use of analgesics with a long half-life (e.g., controlled-release oxycodone) and prophylactic use of analgesics were prohibited.

Subjects were not allowed to be on prophylactic analgesics but were allowed as-needed analgesics for endometriosis-related pain during the baseline data collection period and during the treatment periods of the study. Investigator clinical judgment was the basis for any change in prescription but use of as-needed medication was determined by the subject.

Statistical analysis

The sample size calculation was based on efficacy measures from a previous study (data on file). Based on an effect size of at least 0.54, it was determined that 60 patients per treatment group would yield an 80% power to detect a treatment difference after accounting for a 10% dropout rate.

The safety analysis set included all patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug. The intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis set included all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug and had at least 10 evaluable e-Diary reports during the double-blind period.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the monthly mean assessment of dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia; percentage days of analgesic use; and responses to the EHP-5. Changes from baseline in these assessments were analyzed by an ANCOVA model with treatment as a fixed effect and the baseline value as a covariate. The percentage of patients with at least a 30% reduction from baseline in pain was compared between treatment groups using the Pearson chi-squared test. Descriptive statistics were calculated for PGIC scores, and comparisons between treatment group mean scores were performed using a 1-way ANOVA.

Results

Patient characteristics

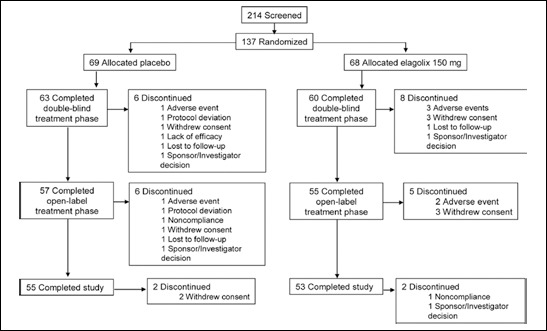

Overall, 137 patients were randomized, 123 patients completed the double-blind period and 112 patients completed the open-label period of the study. Patient disposition and reasons for study discontinuation are presented in Figure 2. Demographic and baseline characteristics, including depth and stage of endometriosis were similar between treatment groups (Tab. I). Overall, 38% of patients had previously participated in an elagolix study with treatment assignment to elagolix, placebo or DMPA. In this study, 36% of patients randomized to placebo and 40% of patients randomized to elagolix had previous elagolix trial experience. None had received elagolix within the preceding year and there were no selection criteria based on prior use of elagolix or response.

Fig. 2.

Patient disposition.

Table I.

PATIENT DEMOGRAPHICS AND BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 69) | Elagolix 150 mg (n = 68) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (range) | 33.0 (21-47) | 33.0 (21-47) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||

| White | 57 (82.6%) | 55 (80.9%) |

| Black | 7 (10.1%) | 6 (8.8%) |

| Hispanic | 5 (7.2%) | 5 (7.4%) |

| Other | 0 | 2 (3.0%) |

| Weight, kg, median (range) | 73.03 (50.0-131.5) | 75.52 (45.1-117.8) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (range) | 26.10 (18.9-45.0) | 28.25 (15.9-38.9) |

| Dysmenorrhea score, median (range) | 3.0 (2.0-3.0) | 3.0 (2.0-3.0) |

| Nonmenstrual pelvic pain score, median (range) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 2.0 (2.0-3.0) |

| Stage of endometriosis, *,† no. (%) | ||

| I | 10 (14.5%) | 13 (19.1%) |

| II | 15 (21.7%) | 18 (26.5%) |

| III | 24 (34.8%) | 18 (26.5%) |

| IV | 8 (11.6%) | 9 (13.2%) |

| Unknown | 12 (17.4%) | 10 (14.7%) |

| Depth of endometriosis,†no. (%) | ||

| Superficial | 28 (40.6%) | 24 (35.3%) |

| Infiltrative | 19 (27.5%) | 17 (25.0%) |

| Unknown | 22 (31.9%) | 27 (39.7%) |

| Months since diagnosis of endometriosis, ‡median (range) | 53.80 (0.7-247.3) | 51.90 (0.7-167.6) |

| Months since last laparoscopy, ‡median (range) | 40.30 (0.7-120.2) | 38.00 (0.7-132.3) |

| Prior treatment for endometriosis, §no. (%) | ||

| Overall | 46 (66.7%) | 48 (70.6%) |

| Investigational drug | 4 (5.8%) | 3 (4.4%) |

| Estrogens | 3 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Gonadotropins and other ovulation stimulants | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Hormonal contraceptives | 33 (47.8%) | 32 (47.1%) |

| GnRH agonists | 21 (30.4%) | 22 (32.4%) |

| Danazol | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.5%) |

| Progestogens | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.5%) |

| Progestogen and estrogen combinations | 11 (15.9%) | 11 (16.2%) |

Stage of endometriosis (according to Revised ASRM endometriosis classification): I: minimal, few or superficial implants are evident; II: mild, more implants and deeper involvement; III: moderate, more implants, with ovaries affected and the presence of adhesions; IV: severe, as with stage III, but with multiple and more dense adhesions.

Stage and depth of endometriosis were based on evaluation at the time of laparoscopy not at baseline.

Number of months relative to the date of first screening procedure.

Patients may have had more than one medication per category.

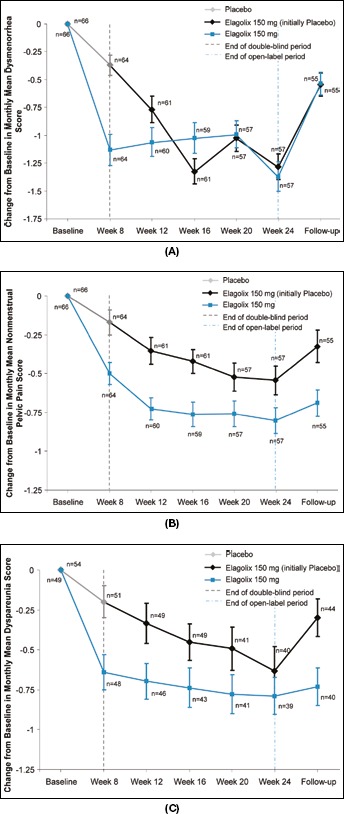

Pelvic pain assessments

Monthly mean scores and changes from baseline for the primary outcome measures of dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia are shown in Figure 3A-C, respectively. There were significantly greater mean reductions from baseline to week 8 in dysmenorrhea (-1.13 ± 0.11 vs. −0.37 ± 0.11, p<0.0001), nonmenstrual pelvic pain (-0.47 ± 0.07 vs. −0.19 ± 0.07, p = 0.0066) and dyspareunia (-0.61 ± 0.10 vs. −0.23 ± 0.10, p = 0.0070) in patients treated with elagolix compared with placebo. Furthermore, there was a higher percentage of patients treated with elagolix who had at least a 30% reduction in pain scores from baseline to week 8 for dysmenorrhea (62.5% vs. 32.8%, p = 0.0008), nonmenstrual pelvic pain (62.5% vs. 32.8%, p = 0.0008) and dyspareunia (57.8% vs. 34.0%, p = 0.0223).

Fig. 3.

Change from baseline in monthly mean dysmenorrhea scores (A), nonmenstrual pelvic pain scores (B) and dyspareunia scores (C).

At the conclusion of the open-label period, the mean changes from baseline were similar in both groups for dysmenorrhea (-1.4 ± 0.1 vs. −1.3 ± 0.1), nonmenstrual pelvic pain (-0.8 ± 0.1 vs. −0.5 ± 0.1) and dyspareunia (-0.8 ± 0.1 vs. −0.6 ± 0.2), for patients initially randomized to elagolix and placebo, respectively. At the week 30 visit (6 weeks posttreatment), the mean reductions from baseline for dysmenorrhea (-0.5 ± 0.1 and −0.5 ± 0.1), nonmenstrual pelvic pain (-0.7 ± 0.1 and −0.3 ± 0.1) and dyspareunia (-0.7 ± 0.1 and −0.3 ± 0.1) were less, compared with those observed during the open-label period for both treatment groups.

A sensitivity analysis was performed on efficacy measures for the double-blind period in patients without prior elagolix trial experience. Results were similar to the overall efficacy results, but the effect size was slightly smaller in these patients. For example, mean dysmenorrhea scores at baseline were 2.08 ± 0.08 for the placebo group (n = 43) and 2.03 ± 0.09 for elagolix (n = 40). After 8 weeks of treatment, the mean changes from baseline, in dysmenorrhea scores were −0.41 ± 0.14 for placebo group and −1.05 ± 0.14 for elagolix group (p = 0.001).

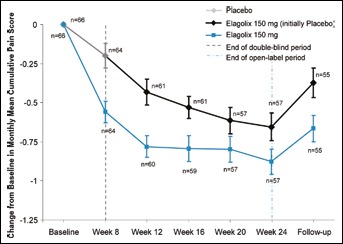

The monthly mean cumulative pain scores were consistent with the results observed for dysmenorrhea, non-menstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia (Fig. 4). During the double-blind period, there were significantly greater mean reductions from baseline to week 8, in cumulative pain in patients treated with elagolix compared with placebo (-0.55 ± 0.1 vs. −0.21 ± 0.1, p = 0.0011). At the conclusion of the open-label period, the change from baseline was similar in both groups for cumulative pain (-0.88 ± 0.1 vs. −0.66 ± 0.1, for patients initially randomized to elagolix and placebo, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Change from baseline in monthly mean cumulative pain scores.

At baseline, the total CPSSS was similar in the elagolix and placebo groups (9.5 ± 0.2 and 9.5 ± 0.3, respectively). There was a significantly greater mean improvement in the CPSSS in the elagolix group compared with placebo during the double-blind period (-4.5 ± 0.4 vs. −2.2 ± 0.4, p<0.0001). After open-label treatment with elagolix, both treatment groups had improvements over baseline in their mean CPSSS (-5.4 ± 0.4 and −5.6 ± 0.5, for patients initially treated with elagolix and placebo, respectively).

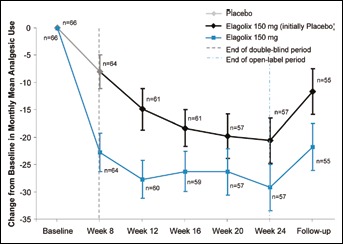

Use of analgesic medications

The use of analgesics decreased in both groups during the double-blind period, but the reduction was significantly greater in patients treated with elagolix compared with placebo (p = 0.0019). The mean change from baseline in the percentage of days per month with any analgesic use is shown in Figure 5. Elagolix treatment produced greater mean reductions in the percentage of days with analgesic use from baseline to week 8, compared with placebo for prescription (-7.2% ± 1.8% vs. −0.8% ± 1.8%, p = 0.0141), narcotic (-4.7% ± 1.4% vs. −1. 2% ± 1.4%, p = 0.0720) and any analgesic use (-21.6% ± 2.8% vs. −9.2% ± 2.8%, p = 0.0019). During the open-label period, analgesic use continued to be reduced from baseline, and the percentage of days with any usage was similar in both groups (-29.2% ± 4.2% vs. −20.6% ± 4.2% at week 24, for patients initially randomized to elagolix and placebo, respectively). At the follow-up visit (week 30), there was an increase in analgesic use from the open-label period, although the percentage of days with analgesic use was still less than baseline (any −21.8% ± 4.3% and −11.6% ± 4.2%, prescription −6.1% ± 2.3% and −0.7% ± 3.1% and narcotic −3.6% ± 1.7% and 0.75% ± 2.7%; for patients initially randomized to elagolix and placebo, respectively).

Fig. 5.

Change from baseline in the monthly mean percentage of days with any analgesic use.

A sensitivity analysis examining responders and nonresponders after classifying any patients with increased analgesic use as nonresponders demonstrated similar results as the overall data set for the proportion of patients achieving at least a 30% reduction in pain scores during the double-blind period.

Quality-of-life measures

During the double-blind period, the mean reduction from baseline to week 8 was significantly greater with elagolix treatment compared with placebo for 4 of the 5 EHP-5 dimensions: pain (-28.3 ± 2.9 vs. −13.0 ± 2.9, p = 0.0003); control and powerlessness (-34.0 ± 3.2 vs. −14.1 ± 3.2, p<0.0001); emotional well-being (-16.8 ± 2.7 vs. −10.6 ± 2.7, p = 0.1115); social support (-26.0 ± 3.4 vs. −14.9 ± 3.4, p = 0.0232); self-image (-22.2 ± 3.1 vs. −8.3 ± 3.1, p = 0.0021). After open-label treatment with elagolix, both groups experienced similar improvements to those observed in patients receiving elagolix treatment in the double-blind period, in all 5 dimensions of the EHP-5.

Patient global impression of change

Patients who received elagolix during the double-blind period also had significantly lower mean PGIC scores compared with placebo-treated patients (2.4 ± 0.2 vs. 3.4 ± 0.2, p = 0.0002), indicating greater improvement. At week 8, 60.3% of patients treated with elagolix reported being “much improved” or “very much improved” compared with 30.2% of placebo-treated patients.

During the open-label treatment period, PGIC scores continued to improve over baseline and were similar in both groups (1.8 ± 0.1 vs. 2.0 ± 0.2 at week 24, for patients initially randomized to elagolix and placebo, respectively); with 86.0% of patients initially randomized to elagolix reporting “much improved” or “very much improved” compared with 73.7% of patients initially randomized to placebo.

Safety

Elagolix was generally well-tolerated. A summary of adverse events occurring during the study is shown in Table II. The incidence of adverse events was similar between the elagolix 150 mg group and the placebo group, during the double-blind period. Over 24 weeks of treatment, the most commonly occurring adverse events in patients who received elagolix were nausea, headache and hot flush, each of which occurred in 9.9% of patients.

Table II.

SUMMARY OF ADVERSE EVENTS OVER 24 WEEKS OF TREATMENT

| Summary of adverse events during the double-blind period (weeks 1-8) | Placebo (n = 69) | Elagolix 150 mg (n = 68) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients experiencing, no. (%) | ||

| Any adverse event | 34 (49.3%) | 35 (51.5%) |

| Any serious adverse events | 3 (4.3%) | 0 |

| Any adverse event leading to | 1 (1.4%) | 3 (4.4%) |

| discontinuation of study drug | ||

| Adverse events in >1 patient | ||

| Hot flush | 1 (1.4%) | 7 (10.3%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 4 (5.8%) | 5 (7.4%) |

| Nausea | 3 (4.3%) | 5 (7.4%) |

| Headache | 3 (4.3%) | 4 (5.9%) |

| Sinusitis | 5 (7.2%) | 2 (2.9%) |

| Summary of adverse events over 24 weeks of treatmenta | Elagolix 150 mg (n = 131) | |

| Patients experiencing, no. (%) | ||

| Any adverse event | 91 (69.5%) | |

| Any severe adverse event | 16 (12.2%) | |

| Any serious adverse event | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Any adverse event leading to discontinuation of study drug | 6 (4.6%) | |

| Deaths | 0 | |

| Adverse events in ≥5% of patients, no. (%) | ||

| Headache | 13 (9.9%) | |

| Hot flush | 13 (9.9%) | |

| Nausea | 13 (9.9%) | |

| Sinusitis | 8 (6.1%) | |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 8 (6.1%) | |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (5.3%) |

Table includes patients who received elagolix in the double-blind period and all patients from the open-label period.

There were no deaths during the study; serious adverse events were experienced by 6 patients (3 placebo patients during double-blind treatment, 1 patient receiving elagolix during open-label treatment and 2 patients posttreatment), none of which were judged by the Investigator to be related to study drug (1 patient with suicidal depression, 2 patients with spontaneous abortion [described below], 1 patient with lower abdominal pain, 1 patient with bipolar disorder and 1 patient with seizures). The only serious adverse event experienced during elagolix treatment was appendicitis, which occurred during the open-label period.

The mean percentage of days with any uterine bleeding was reduced from 23.0% at screening, to 14.0% during double-blind treatment with elagolix, while the mean percentage of days with any uterine bleeding did not decrease in patients treated with placebo (24.3% vs. 23.9%). The overall reduction in uterine bleeding with elagolix was primarily due to reductions in the percentage of days with moderate to heavy bleeding. Based on bleeding data from the e-Diary, 17 patients (25.8%) in the elagolix group were amenorrheic during the 8-week placebo-controlled treatment period, but of those patients, only 5 (7.6%) maintained amenorrhea during the 24 weeks of treatment. No patients discontinued from the study as a result of their uterine bleeding pattern. In most women, treatment with elagolix resulted in regular cycles associated with longer intervals between menses and a low rate of breakthrough bleeding and spotting (data not shown). After discontinuation of treatment, the median number of days to first menstruation was 24 days (range 1 to 45 days).

There were 5 pregnancies during the study: 3 during the treatment period (1 placebo patient and 2 patients receiving elagolix therapy) and 2 during the posttreatment follow-up period. The 1 placebo patient and 1 of the patients who became pregnant during the posttreatment period had spontaneous abortions. The 3 other pregnancies (all in the elagolix arm, with 2 during treatment and 1 during follow-up) resulted in delivery of 3 healthy full-term infants.

There were no clinically meaningful changes in laboratory results, vital sign measurements or ECG readings during the study. No significant changes in low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) or total cholesterol were noted.

Discussion

In this study, during the double-blind period, treatment with elagolix 150 mg daily was associated with statistically significant reductions in endometriosis-associated dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia, using daily pain scales. In addition, the statistically significant change of −4.5 from baseline in CPSSS for elagolix-treated patients during the double-blind period represented a robust 47% improvement with elagolix treatment. These effects were maintained during the open-label phase for up to 24 weeks. This was the first study to use these modified daily Biberoglu-Behrman pain scales for endometriosis-associated pain. Consistent with previous studies of endometriosis, a reduction in pelvic pain was also observed in the placebo group (22). However, the consistent, significantly higher level of improvement in the elagolix group across multiple outcome measures demonstrated the efficacy of the compound.

In addition to beneficial reductions in pelvic pain, elagolix was associated with a significant reduction in analgesic use and positive improvements in quality-of-life assessments. Recent studies have highlighted the impact of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain as a major driver in loss of work productivity. Those studies have demonstrated the importance of showing improvement in quality-of-life and work productivity end points in endometriosis trials (5, 6).

Elagolix was well-tolerated over 24 weeks of treatment with very few discontinuations due to adverse events. Treatment-related adverse events were generally mild-to-moderate and were consistent with the drug's mechanism of action. In contrast to progestins (15, 23, 24), there was no irregular uterine bleeding or overall increase in bleeding with the use of elagolix therapy. Patients who received elagolix experienced an overall reduction in bleeding, with fewer days of moderate to heavy bleeding. In addition, most women who received elagolix had regular but prolonged cycles (longer interval between menses) with a low rate of breakthrough bleeding and spotting. Also contrary to injectable GnRH agonists or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, which may be associated with a delay in the return of regular menses (24-26), resumption of menses was rapid after discontinuation of elagolix, which may be desirable in women who wish to conceive. Elagolix treatment was associated with a low incidence of hot flush and did not alter serum lipids, changes which have been reported with the use of other hormonal therapies.

One limitation of the current study was the short duration of the double-blind treatment period; however, the length of the double-blind treatment period did allow detection of treatment differences between elagolix and placebo for reducing dysmenorrhea, nonmenstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia, which were the main outcomes of this study. Maintaining patients who are experiencing moderate to severe pain on placebo for longer durations is challenging and may have resulted in a higher dropout rate and weaker power to detect treatment differences (14). An additional limitation was the inclusion of patients with previous elagolix trial experience, although the overall efficacy results were similar in patients with and without previous trial experience.

In addition, because this was a phase II study specifically designed to evaluate efficacy using new daily pain scales, hormone levels were not measured; therefore, correlations between the efficacy of elagolix and hormone levels could not be assessed. In a previous phase I study, patients who were 7 ± 1 days after the onset of menses (cohorts of 6 patients each) received elagolix 50 mg once daily (q.d.), elagolix 100 mg q.d., elagolix 200 mg q.d., elagolix 100 mg twice daily (b.i.d.) or placebo for 7 days (11). In the placebo group, estradiol concentrations were initially between 24 and 75 pg/mL (patients synchronized at cycle day 2-7) and continued to increase consistent with the normal rise of estradiol during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (11). In contrast, in patients who received elagolix for 7 days, mean estradiol concentrations remained within 34 to 68 pg/mL, even with 2 escapes skewing the higher end of the range (1 each from the 100 mg and 200 mg q.d. groups) (11). In the 100 mg b.i.d. group, estradiol was highly suppressed, with mean estradiol during days 1-7 only reaching 17 pg/mL (11). In addition, elagolix delivered at doses of 150 mg was demonstrated to maintain estradiol in the low-normal range in previous phase II studies (12, 13), and it is expected that estradiol was similarly suppressed in the current study, although demonstration of estradiol suppression was not an objective. However, consistent with partial estradiol suppression, a relatively low incidence of hypoestrogenic side effects, including hot flush (9%), was observed. All reports of hot flush were mild or moderate, and none led to discontinuation.

BMD was not measured in this study. However, previous elagolix phase II studies of 6-month duration showed a minimal BMD loss at the target dose of 150 mg, which was not clinically meaningful (Neurocrine Biosciences, data on file). These studies will be reported separately.

Despite the protocol requirement to use dual nonhormonal contraception, there were 3 pregnancies that occurred during the treatment period of this study (1 placebo patient and 2 patients receiving elagolix therapy). The pregnancy occurring in the placebo patient resulted in a spontaneous abortion, and the 2 occurring in the elagolix treatment arm resulted in full-term healthy deliveries, without complications. An additional pregnancy in the elagolix arm that occurred during follow-up also resulted in a full-term healthy delivery without complications, while the remaining pregnancy (during follow-up) in the placebo arm resulted in a spontaneous abortion.

A review of all of the data from the early clinical development program of elagolix to date estimates an annualized pregnancy rate of ∼3%-5% for those receiving the 250 mg q.d. dose and 150 mg q.d. dose, respectively (AbbVie, data on file). Preclinical studies with elagolix have revealed no teratogenic effects at all doses studied (×30-×98 the clinically relevant dose; AbbVie, data on file). This study was a phase II study and was not designed to detect low-frequency adverse events. Additional studies are warranted to determine the long-term safety and efficacy of elagolix for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pelvic pain.

In conclusion, in this study, elagolix showed an acceptable safety and tolerability profile, as well as the potential to reduce chronic pelvic pain for up to 24 weeks of treatment in women with a history of endometriosis. Elagolix is in clinical development as a potential treatment option for women with endometriosis.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Amanda J. Fein, PhD, of AbbVie and Elaine Hanna, MA, contracted by AbbVie. The authors would also like to thank the following investigators: Micah Harris, MD; Parke J. Hedges, MD; William D. Koltun, MD, FACOG; Richard A. Krause, MD; Robin Kroll, MD; Franklin G. Morgan, Jr., MD; R. Lamar Parker, MD; Prescott W. Prillaman, MD; Ishrat Rafi, MD, MPH; Jose M. Ruiz, MD; Robert L. Smith, Jr., MD; Michael L. Twede, MD, FACOG; Noel Williams, MD; Edward Zbella, MD.

Footnotes

Financial Support: This study was designed and funded by Neurocrine Biosciences. Elagolix is being developed by AbbVie and Neurocrine Biosciences. Neurocrine Biosciences, AbbVie and all authors participated in data analysis and interpretation. AbbVie provided funding for writing support. All authors contributed to the development of the content. The authors and AbbVie reviewed and approved the manuscript; the authors maintained control over the final content.

Conflicts of Interest: B.C. has received grant support from Neurocrine Biosciences and has been a consultant for AbbVie (formerly Abbott), and also received research grants from Syneract and Evofem. L.G. was a consultant to Neurocrine Biosciences and AbbVie; currently nothing to disclose. W.P.D. has been a consultant for Neurocrine Biosciences and AbbVie. J.B., R.J. and C.O.B. are Neurocrine Biosciences employees and own Neurocrine Biosciences stock. K.C., S.H., M.F. and P.J. are AbbVie employees and own AbbVie stock.

References

- 1.Carr B.R., ed. Endometriosis. In: Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, et al., eds. Williams gynecology. 2nd ed. Chap. 10. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins – Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 51: chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 103(3): 589–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2008; 90(5)(Suppl): S260–S269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao X., Yeh Y.C., Outley J., Simon J., Botteman M., Spalding J. Health-related quality of life burden of women with endometriosis: a literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006; 22(9): 1787–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fourquet J., Báez L., Figueroa M., Iriarte R.I., Flores I. Quantification of the impact of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life and work productivity. Fertil Steril. 2011; 96(1): 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nnoaham K.E., Hummelshoj L., Webster P. et al. ; World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women's Health Consortium. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011; 96(2): 366, e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batzer F.R. GnRH analogs: options for endometriosis-associated pain treatment. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006; 13(6): 539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olive D.L. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359(11): 1136–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surrey E.S. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and add-back therapy: what do the data show? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 22(4): 283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuldeore M.J., Marx S.E., Chwalisz K., Smeeding J.E., Brook R.A. Add-back therapy use and its impact on LA persistence in patients with endometriosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010; 26(3): 729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Struthers R.S., Xie Q., Sullivan S.K. et al. Pharmacological characterization of a novel nonpeptide antagonist of the human gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor, NBI-42902. Endocrinology. 2007; 148(2): 857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Struthers R.S., Nicholls A.J., Grundy J. et al. Suppression of gonadotropins and estradiol in premenopausal women by oral administration of the nonpeptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist elagolix. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009; 94(2): 545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imani R., Thai-Cuarto D., Jimenez R., Burke J., Kroll R., O'Brien C. Petal study: safety, tolerability and effectiveness of elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3): S111–S112. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dlugi A.M., Miller J.D., Knittle J.; Lupron Study Group. Lupron depot (leuprolide acetate for depot suspension) in the treatment of endometriosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Fertil Steril. 1990; 54(3): 419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlaff W.D., Carson S.A., Luciano A., Ross D., Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous injection of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate compared with leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2006; 85(2): 314–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams D.A., Gendreau M., Hufford M.R., Groner K., Gracely R.H., Clauw D.J. Pain assessment in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a consideration of methods for clinical trials. Clin J Pain. 2004; 20(5): 348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giske L., Sandvik L., Røe C. Comparison of daily and weekly retrospectively reported pain intensity in patients with localized and generalized musculoskeletal pain. Eur J Pain. 2010; 14(9): 959–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009. Available at: http://www.ispor.org/workpaper/FDA%20PRO%20Guidance.pdf.

- 19.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. Good clinical practice. Available at: http://ichgcp.net/. Accessed June 28, 2011.

- 20.Biberoglu K.O., Behrman S.J. Dosage aspects of danazol therapy in endometriosis: short-term and long-term effectiveness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981; 139(6): 645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones G., Jenkinson C., Kennedy S. Development of the Short Form Endometriosis Health Profile Questionnaire: the EHP-5. Qual Life Res. 2004; 13(3): 695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hrobjartsson A., Gotzsche P.C. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; CD003974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crosignani P.G., Luciano A., Ray A., Bergqvist A. Subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate versus leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Hum Reprod. 2006; 21(1): 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vercellini P., Fedele L., Pietropaolo G., Frontino G., Somigliana E., Crosignani P.G. Progestogens for endometriosis: forward to the past. Hum Reprod Update. 2003; 9(4): 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arias R.D., Jain J.K., Brucker C., Ross D., Ray A. Changes in bleeding patterns with depot medroxyprogesterone acetate subcutaneous injection 104 mg. Contraception. 2006; 74(3): 234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surrey E.S., Hornstein M.D. Prolonged GnRH agonist and add-back therapy for symptomatic endometriosis: long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 99(5 Pt 1): 709–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]