Abstract

Introduction:

Chemoimmunotherapeutic regimens using the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab improved significantly the survival rates in various B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs), including chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The next-generation CD20 antibody obinutuzumab represents an addition to the drug armamentarium used for the therapeutic management of patients with LPDs.

Areas covered:

Herein, the authors discuss the biochemical and conformational engineering of obinutuzumab to increase antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and direct cell death. They also describe the available preclinical data on obinutuzumab’s role in B-cell LPDs. Furthermore, the authors summarize the Phase I and II clinical trials of obinutuzumab, focusing on the main pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic characteristics, the most common clinically significant adverse events, dose optimization, and clinical outcomes of patients with CLL and other B-cell LPDs treated with obinutuzumab as monotherapy or in combination with other agents. To put these data in perspective, the use of obinutuzumab is compared with that of rituximab in CLL and other B-cell LPDs.

Expert opinion:

Clinical trials have demonstrated that obinutuzumab is well tolerated. The novel mechanism of action of obinutuzumab is associated with significant efficacy in CLL and other B-cell LPDs. Ongoing clinical trials are expected to determine the optimal use of obinutuzumab in these diseases.

Keywords: monoclonal antibody, CD20, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, obinutuzumab, rituximab

1. Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a B-cell chronic lymphoproliferative disorder (LPD) characterized by the accumulation of monoclonal functionally incompetent lymphocytes. It represents approximately 30 percent of all leukemias in the United States1; its incidence ranges from 3.65 to 6.75 per 100,000 population per year2. The median age at diagnosis is 70 years,3 and thus it is considered a disease of older adults, although it is can affect even young adults4. In 2017, the annual incidence of new cases of CLL in the United States is estimated to be approximately 20,0001

Clinical and biological studies have shown that CLL is a heterogeneous disease. The therapeutic management of patients with CLL varies among patients. A meta-analysis of the timing and intensity of therapy for patients with CLL showed that there is no evidence of benefit from early (at diagnosis) treatment in most patients with CLL5. When treatment is indicated, usually in symptomatic patients with “active disease” or advanced disease, the selection of treatment should take into consideration the patient’s age, clinical performance status, and comorbidities, in addition to disease characteristics. The treatment of patients with CLL usually includes (1) chemotherapeutic agents such as purine analogs (e.g. fludarabine) and alkylating agents (e.g. chlorombucil), (2) monoclonal antibodies (e.g. rituximab, ofatumumab, and obinutuzumab), and/or (3) Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (e.g. ibrutinib).

The use of chemoimmunotherapy (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab [FCR]) in patients with CLL (preferably < 70 years old) was associated in phase III clinical trials with high rates of overall and complete response, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival; and significantly longer PFS and overall survival compared to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide 6–12. In addition, durable progression-free survival (PFS) following FCR is noted in patients with IGHV mutated CLL without del17p 9. However, fludarabine-based therapy is associated with serious adverse events that include myelosuppression, resulting in infections and hemolytic anemia. Despite the prolonged duration of PFS, most patients experience disease recurrence. In addition, the treatment options for elderly patients – who are unable to tolerate fludarabine-based therapy – are limited. Therefore the therapeutic management of patients needs to be optimized using drugs with improved tolerability profile and higher efficacy.

Obinutuzumab, a CD20-directed cytolytic antibody (mAb), was engineered to improve the clinical outcomes of CD20-positive LPDs. This review focuses on the pre-clinical and clinical development of obinutuzumab, including results of clinical trials.

2. Obinutuzumab Development and Mechanism of Action

Obinutuzumab (originally GA101) is a fully humanized, a type II anti-CD20 monoclonal IgG1 antibody. The molecular weight of obinutuzumab is 146.1 kDa. In the United States, obinutuzumab is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in combination with chlorambucil for the treatment of patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia; and in combination with bendamustine followed by obinutuzumab monotherapy, for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma who relapsed after, or are refractory to, a rituximab-containing regimen. 13,14 It is also approved in Europe by the European Medicines Agency for the same indications.15.

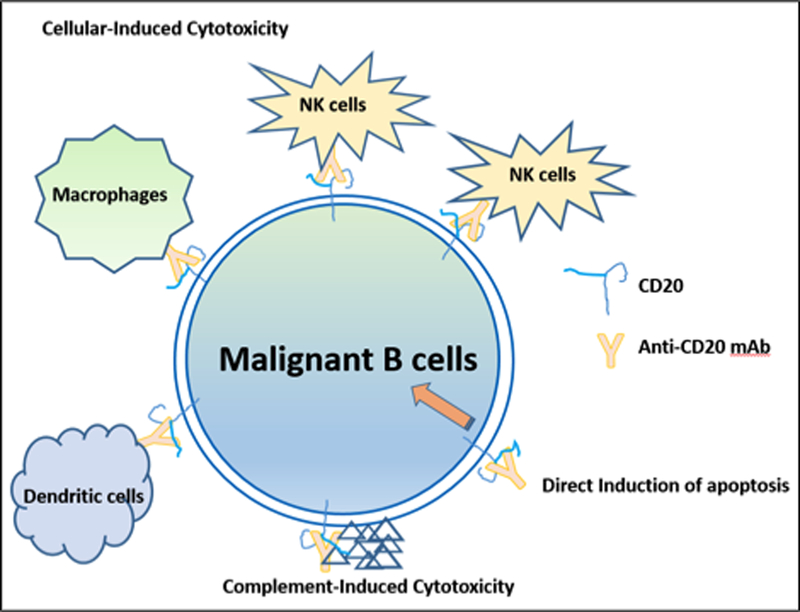

The transmembrane B-lymphocyte receptor CD20 appears to play a role in calcium entry and the store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) channels,16 which are involved in B-cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation17. Many anti-CD20 agents have been developed; these agents differ in mechanism of action, and, consequently, results 18. Once bound to CD20, type I anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (e.g. rituximab and ofatumumab) activate the process of complement-dependent cytotoxicity, stimulate apoptosis signaling, and enhance the recruitment of immune-mediator cells, leading to antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity19 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanism of Action of Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibodies

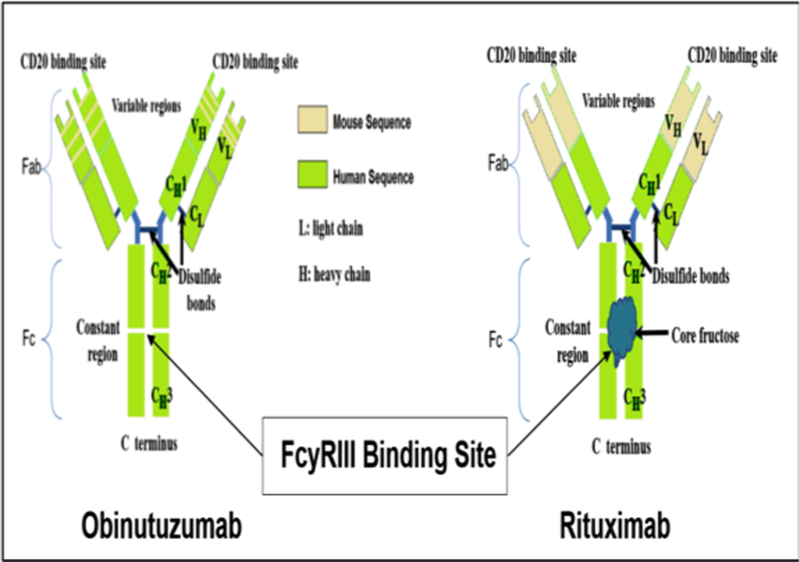

Obinutuzumab was engineered to increase immune cell killing compared to rituximab (Figure 1 & 2). It binds to the CD20 epitope that partially overlaps with the section recognized by rituximab in a unique conformation20. The biochemical characteristics of obinutuzumab allow the binding of its two Fab on the same CD20 tetramer (intra-CD20-tetramer binding vs. inter-CD20-tetramer binding of type I anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies)21. As in FcgRIIIa binding monoclonal antibodies, glycoengineering of the Fc portion of obinutuzumab reduces fucosylation, which leads to enhanced affinity for the FcγRIIIa receptor on NK cells, resulting in the activation of signaling molecules and the promotion of cytoskeletal rearrangement and degranulation. 18,22–25.

Figure 2.

Simplified Schema of Biochemical Differences Between Obinutuzumab and Rituximab

The use of rituximab induces the redistribution of CD20 into lipid rafts, which is not noted with obinutuzumab. The instability of CD20 in lipid rafts is fundamental for complement-dependent cytotoxicity and therefore, obinutuzumab is more effective at inducing B-cell death via effector cells and non-effector cells such as lysosomal-dependent programmed cell death 23,24,28. Based on the mechanism of action, obinutuzumab is theoretically expected to provide greater efficacy than rituximab or ofatumumab, 20,23.

3. Preclinical Data

The activity of obinutuzumab against malignant B-lymphocytes has been studied extensively in the preclinical setting. The anti-neoplastic effect of obinutuzumab was proven greater than that of other anti-CD20 mAbs, including rituximab. Mössner et al demonstrated higher efficacy of obinutuzumab against the aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) model (SUDHL4 cells) when compared to either rituximab or ofatumumab; obinutuzumab was found to induce complete remission (CR), which was not noted with rituximab and ofatumumab24. Herting et al demonstrated that obinutuzumab induces tumor growth control in a dose-dependent manner in rituximab-refractory DLBCL WSU-DLCL2 xenograft mouse models29. Furthermore, longer overall survival was seen in a xenograft model of mantle cell lymphoma (Z138 MCL cells in SCID mice) with obinutuzumab compared to rituximab29. The combination of obinutuzumab and chemotherapy (chlorambucil, fludarabine, bendamustine, or cyclophosphamide) had higher antitumor activity than the combination of rituximab and chemotherapy in various mouse xenograft models29,30. Finally, both obinutuzumab and rituximab were highly efficient in depleting B-lymphocytes from the peripheral blood, but only obinutuzumab depleted efficiently B-cells (except for memory B-cells and long-lived plasma cells) from the deep lymphoid tissue, such as the spleen and lymph nodes24.

4. Pharmacokinetics and Dose Selection

The pharmacokinetic data on obinutuzumab were derived mainly from the phase I/II GAUGUIN31,32 and phase IB GAUDI clinical studies33. In the GAUDI trial, the initial dose (1600 mg)/subsequent dose (800-mg) arms achieved higher mean obinutuzumab serum concentrations compared to the 400/400-mg arms, and this higher serum concentration translated into higher CR rates.

In the escalating phase of the GAUGUIN trial, patients received up to nine infusions (day 1 and 8 of the first cycle, then only day 1 of the subsequent cycles) of single-agent obinutuzumab at doses ranging from 50 mg to 2,000 mg. The first dose was only 50% of the assigned cohort dose. Pharmacokinetic data demonstrated that at cohort dose levels lower than 400/800 mg, the serum obinutuzumab concentrations were substantially lower compared to dose levels higher than 400/800 mg34. Additionally, there was a tendency for serum concentrations to increase over the treatment course. The mean Cmax and Ctrough values increased as doses increased (highest concentrations with obinutuzumab 1200/2000 mg). Interestingly, the mean Cmax and Ctrough values increased from the initial dose through the last dose without reaching a steady state concentration for any of the dose levels used31.

Based on the results of the phase 1 GAUGUIN trial in patients with CLL, in the phase II part of the study, two doses of obinutuzumab were investigated in patients with NHL32: (1) 400mg/400 mg and (2) 1600mg/800 mg. In the high-dose cohort, Ctrough reached a steady state of 300 μg/mL by cycle 3. In the low-dose cohort, Ctrough was lower throughout without reaching a steady state (100 – 200 μg/mL). In addition, differences in the blood concentration of obinutuzumab by gender and body weight (higher levels in females and patients with lower body weight) were noted in the low-dose cohort but not in the high-dose cohort.

Accumulating pharmacokinetic data of obinutuzumab demonstrate that drug elimination is faster in the first cycle compared to subsequent cycles. This observation raises the question whether a higher dose is needed during the first cycle. As the same dose for initial and subsequent administrations is more practical and desirable, 1000 mg of obinutuzumab on days 1, 8, and 15 of the first cycle and on day 1 of the subsequent cycles was used later in the phase II GAUGUIN trial in patients with CLL31. The use of pharmacokinetic simulation showed that this regimen with the single standard dose could achieve a Ctrough similar to that seen with the 1600/800 mg regimen. Therefore, the fixed dose regimen (1000 mg C1D1, D8, D15 and C1D1 for the subsequent cycles) was adopted for further clinical trial development, and it was also the FDA-approved dose. In the GAUGUIN trial, no relationship between pharmacokinetics and clinical response or tumor burden has been found owing to the small number of patients with responded to treatment. The depletion of CD19+ B-cells occurred rapidly after the first obinutuzumab infusion, but in the majority of patients B-cells recovered (>.7 × 109/L) within 24 months after the last dose31,32.

5. Clinical Trials of Obinutuzumab as Monotherapy or in Combination Regimens

The clinical development of obinutuzumab was based on studies in patients with various CD20+ LPDs. The approval of obinutuzumab in CLL was based on a phase III trial 35. The clinical trials of obinutuzumab as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy in CD20+ LPD, focusing on CLL are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Clinical Trials of Obinutuzumab in Patients with CLL

| Trials | Phase | Dose, mg | No. of Pts. | Treatment | Best Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAUGUIN25 | I | 400–1200 | 13 | O | PR 62% (n=8) SD 23% (n=3) |

| II | 1000 | 20 | O | CR 5% (n=1) PR 25% (n=5) SD 25% (n=5) |

|

| GALTON39 | Ib | 1000 | 20 | O+B | CR 20% (n=4) CRi 25% (n=5) PR 45% (n=9) |

| 21 | O+FC | CR 10% (n=2) CRi 14% (n=3) PR 38% (n=8) SD 19% (n=4) |

|||

| GAGE40 | II | 1000 | 41 | O | CR 5% (n=2) CRi 0 (n=0) PR 44% (n=18) |

| 2000 | 39 | O | CR 15% (n=6) CRi 5% (n=2) PR 46% (n=18) |

||

| CLL1135,41 | III | 1000 | 118 | C | PR 31% (n=37) |

| 333 | OC | CR 21% (n= 69) PR 58% (n= 192) |

|||

| 330 | RC | CR 7% (n= 23) PR 58% (n= 192) |

Abbreviations: O, obinutuzumab; B, bendamustine; FC, fludarabine/cyclophosphamide; R, rituximab; CR, complete remission; CRi, complete remission with incomplete marrow recovery; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; C, chlorambucil; OC, obinutuzumab and chlorambucil, RC, rituximab and chlorambucil

5.1. Phase I Clinical Trials

The first-in-human trial of obinutuzumab was a multicenter Phase I study (GAUGUIN)31,34, with a classical “3+3” design. Patients with various CD20+ LPDs were eligible; and data were reported separately in patients with NHL from those with CLL. Twenty-one heavily pretreated patients with relapsed or refractory CD20+ NHL were enrolled. There were seven dose-escalating cohorts with the following initial/subsequent doses: (1) cohort 1: 50/100 mg, (2) cohort 2: 100/200 mg, (3) cohort 3: 200/400 mg, (4) cohort 4: 400/800 mg, (5) cohort 5: 800/1,200 mg, (6) cohort 6: 1,200/2,000 mg, and (7) cohort 7: 1,600/800 mg. A total number of 9 infusions were given, each every 3 weeks. No dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were reported. IRRs were mainly mild (grade 1–2, 98%) and predominantly seen during the first infusion. The IRRs were reversible with decrease of the infusion rate, infusion interruption, and/or corticosteroids; and all patients received all the scheduled doses. Circulating cytokine levels were higher after the first infusion but became lower with subsequent infusions.

Results from patients with refractory/relapsed CLL enrolled in the GAUGUIN trial were recently reported. Of 33 patients with CLL who were enrolled on the study, 39% (n=13) received escalating doses (phase 1) ranging from 400 to 1200 mg on days 1 and 8 of cycle 1 and on day 1 of cycles 2–8. The remaining 61% (n=20) received a fixed dose (phase 2) consisting of 1000 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of cycle 1 and on day 1 of cycles 2–8. Grade 3/4 neutropenia was noted in 33% of patients (n=11, 7 in phase 1 and 4 in phase 2). All patients had IRRs, but 25% (n=5) were grade 3–4.

Another phase I trial using obinutuzumab as monotherapy was conducted in Japanese patients36. A total of 12 patients with CD20+ B-cell lymphoma were enrolled. Patients received escalating dose levels of intravenous obinutuzumab in up to nine infusions per patient. B-cell lymphopenia was observed after the initial infusion and continued throughout the duration of treatment in all patients. Overall, obinutuzumab was safe and no DLTs were reported.

The third phase I trial using obinutuzumab as monotherapy in relapsed/refractory CD20+ NHL or CLL was the GAUSS trial37. In this trial, 22 patients were enrolled at escalating dose levels (initial dose/subsequent doses): 100/200 mg, 200/400 mg, 400/800 mg, 800/1,200 mg, 1,200/2,000 mg, and 1,000/1,000 mg. The trial had an induction phase (weekly infusions for 4 weeks) followed by a maintenance phase (infusions once every 3 months). The maximum number of infusions administered was eight. Of 22 patients, 21 completed the induction phase and eight started the maintenance phase. Overall, 86% (13 of 19) of patients were rituximab-refractory (no response within 6 months of treatment). There were no DLTs and the majority of the adverse events were grade 1/2 IRRs. Grade 4 IRRs were reported in one patient with CLL, leading to discontinuation of treatment during the first infusion. Grade 1/2 infection was noted in 32% of patients during the induction phase. Grade 3 respiratory infection was reported in the maintenance phase, not requiring drug discontinuation.

In a phase 1B trial in previously untreated patients with follicular lymphoma (GAUDI), the combination of obinutuzumab and chemotherapy (CHOP and bendamustine) was safe and overall well tolerated 33,38. In another parallel-cohort, non-randomized, phase 1B, multicenter study, the combinations of obinutuzumab and bendamustine or obinutuzumab and FC were studied in treatment-naïve patients with CLL (the GALTON trial) 39. A total of 41 patients were enrolled. Patients were to receive up to six cycles (mean, 5.7 and 5.1 cycles for the bendamustine and FC combination, respectively) and were assigned to either the bendamustine combination regimen (n = 20) or the FC combination regimen (n = 21). Obinutuzumab was administered IV (100 mg on day 1, 900 mg on day 2, and 1000 mg on day 8 and day 15 of cycle 1; 1000 mg on day 1 of cycles 2–6). The chemotherapy regimens were administered as follows: fludarabine 25 mg/m2 IV and cyclophosphamide 250 mg/m2 IV on days 2–4 of cycle 1 and days 1–3 of subsequent cycles; bendamustine 90 mg/m2 IV on days 2–3 of cycle 1 and days 1–2 of subsequent cycles. The most common AEs were IRR (grade 3–4, 20%) and neutropenia (grade 3–4, 55% and 48% in the bendamustine and FC combination, respectively).

5.2. Phase II / III Clinical Trials

The efficacy of monotherapy obinutuzumab in CLL and dosage optimization were investigated in another randomized phase II trial (GAGE)40. Eighty previously untreated patients with CLL were randomized to receive obinutuzumab in (1) a low-dose arm consisting of 100 mg on day 1, 900 mg on day 2, and 1000 mg on days 8 and 15 of cycle 1 and 1000 mg on the first day of each subsequent cycle 2–8 or (2) a high-dose arm consisting of 100 mg on day 1, 900 mg on day 2, 1000 mg on day 3, and 2000 mg on days 8 and 15 of cycle 1 and 2000 mg on the first day of each subsequent cycle 2–8. The demographic characteristics of patients were similar in the two groups; 10% had del 17p and 41% had high-risk Rai disease. Obinutuzumab was safe. The high-dose arm was associated with higher overall response rates than the low-dose arem (67% vs. 49%, p=.08 and CR 20% vs. 5%, p<0.05). However, no difference in the PFS duration was noted between the two arms, indicating that the dose-response relationship should be further investigated.

A pivotal, multinational, phase III trial, CLL11, was designed by the German group GCLLSG35. Previously untreated patients with CLL and significant comorbidities (cumulative illness rating scale score of >6 and/or 30 mL/min < creatinine clearance < 70 mL/min) were randomized to receive (1) obinutuzumab in combination with chlorambucil (OC), (2) chlorambucil alone (C), or (3) chlorambucil in combination with rituximab (RC). Obinutuzumab was administered at 1000 mg IV on days 1, 8, and 15 of the first cycle and the first day of each subsequent cycle to a maximum of six cycles. Both rituximab and chlorambucil were administered at standard doses: (1) rituximab 375 mg/m2 IV on day 1 of the first cycle and 500 mg/m2 on day 1 of the subsequent five cycles and (2) chlorambucil 0.5 mg/kg on days 1 and 15 of each cycle. To improve tolerability and decrease IRRs, the protocol was amended to deliver the first dose of obinutuzumab in 2 days: 100 mg on day 1 and 900 mg on day 2.

Overall, 781 patients (median age, 73 years) were enrolled. The treatment arms C, OC, and RC included 118, 238, and 233 patients, respectively. Initial pairwise combinations among the three groups demonstrated that the addition of anti-CD20 antibody (whether rituximab or obinutuzumab) was associated with increased clinical benefit compared to chlorambucil monotherapy. The overall response rates were 31% (no CR), 77% (22% CR), and 66% (7% CR) in the C, OC, and RC arms, respectively (p<0.001). The highest rate of minimal residual disease was seen in the OC treatment arm. The highest median PFS duration (median follow-up, 23 months) was 29 months in the OC arm; 15 months in the RC arm; and 11 months in the C arm (p<0.001). After the initial analysis, more patients were enrolled in the OC (n=333) and RC (n=330) treatment arms. A head-to-head comparison of both arms showed that the overall response rate was significantly higher in the OC arm (78% vs. 65%; CR: 21% vs. 7%, p<0.001). The rate of negative testing for minimal residual disease was higher in the OC arm than in the RC arm (bone marrow: 20% vs. 3%; peripheral blood: 38% vs. 3%, p<0.001); and PFS duration was longer in the OC arm compared to the RC arm (27 months vs. 15 months, p<0.001). Despite the clinical benefit seen in the OC arm, overall survival was not statistically different between the two treatment arms (hazard ratio (HR) = .6, p=.08), but it improved when obinutuzumab was added to chlorambucil (OC vs. C; HR: .4, p=0.002). Recent updates of CLL11 with longer follow-up confirmed the above findings with significant delay to the next treatment (38 months in the RC arm vs. 51 months in the OC arm, p< 0.0001)41.

The efficacy of obinutuzumab was also studied in both DLBCL and follicular lymphoma. In the GOYA trial, 1,418 previously untreated patients with DLBCL were randomized to CHOP regimen in combination with either obinutuzumab (G-CHOP, n=706) or rituximab (R-CHOP, n= 712)42. The primary endpoint (PFS) was not met. The 3-year PFS rates were 66% and 69% in R-CHOP and G-CHOP, respectively. In the GALLIUM study, 1202 previously untreated patients with follicular lymphoma were randomized to either (1) obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy followed by obinutuzumab maintenance (O-chemo) or (2) rituximab plus chemotherapy with rituximab maintenance (R-chemo). Chemotherapeutic regimens included CHOP, CVP, or bendamustine43. The difference in the 3-year PFS rate between the two groups was statistically significant (80% vs. 73% in O-chemo and R-chemo, respectively) and translated into a 34% reduction in the risk of progression or death (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51, 0.85; p=0.001). In another multicenter, phase III trial (GADOLIN), 396 patients with rituximab-refractory indolent NHL were randomized to receive either bendamustine or bendamustine with obinutuzumab. PFS was significantly longer in the obinutuzumab with bendamustine arm (median not reached vs. 14.9 months; HR, 55; p=0·0001)44.

6. Expert Opinion

Despite the significant improvement in the treatment of patients with CLL, as evidenced by durable responses and increased overall survival with effective chemoimmunotherapy, complications of CLL remain the most common cause of death in these patients. Targeting the pan B-cell antigen CD20 receptor with rituximab has clearly improved the clinical outcomes and has is an overall acceptable toxicity profile. Obinutuzumab enhances the immune cell killing compared to rituximab, likely owing to improved antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

The clinical development of obinutuzumab is evolving. The initial data suggest that obinutuzumab is associated with a higher objective response rate compared to rituximab. However, results of rituximab and obinutuzumab should be interpreted with caution, taking into consideration that obinutuzumab is administered at higher doses compared to rituximab. Although some earlier clinical studies of rituximab were disappointing 45,46, subsequent trials demonstrated that higher doses of rituximab were associated with improved efficacy. 47,48

An important challenge with obinutuzumab is the development of IRRs, which was the main reason for treatment discontinuation in the CLL11 study. Treatment discontinuation was more frequent compared to that of prior phase I and II trials. The frail patient population in CLL11 could partially explain the higher rate of treatment discontinuation. Although the explanation is unclear, the release of significant amounts of cytokines such as TNF, IL-6, and IL-8 may explain the higher rate of IRRs noted with obinutuzumab compared to rituximab 23,49–51. No clinical or biological biomarkers have been identified to predict IRR development and its severity with the first infusion. The risk of IRRs can be minimized by adopting the following measures: (1) administration of the first dose over 2 days (100 mg on day 1; and 900 mg on day 2), (2) adequate hydration, (3) access to a second intravenous cannula and a resuscitation equipment, (4) avoidance of antihypertensive medications 12 hours prior to the initiation and until at least 1 hour after completion of the infusion, and (5) pre-medication with corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 80 mg or dexamethasone 20 mg), antihistamine and paracetamol 52. If IRRs occur, the infusion rate should be decreased with close monitoring, supplemental oxygen, and treatment for fevers, chills and/or rigor52. If grade 4 IRRs occur, the infusion should be stopped permanently; re-challenge is hazardous and not recommended.

Ongoing phase II trials will determine the efficacy and tolerability of obinutuzumab in combination with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide or bendamustine in treatment-naïve and pretreated patients with CLL (NCT02071225, NCT02320487 and NCT02320383). A phase IIIB multicenter, open-label trial is exploring the safety and efficacy of obinutuzumab alone or in combination with chemotherapy (bendamustine, chlorambucil, or cyclophosphamide/fludarabine) in fit and unfit untreated or pretreated patients with CLL (NCT01905943) (GREEN trial). A preliminary analysis on 158 patients in previously untreated patients with CLL (74 fit, 84 non-fit) who received obinutuzumab and bendamustine demonstrated that this combination is well tolerated; and most adverse events were expected and manageable including IRRs (56%) and neutropenia (50%). The observed ORR was 79% (CR+incomplete CR, 32%)53. In recent years, novel agents for the treatment of CLL, including the small molecule kinase inhibitors such as ibrutinib (Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor), idelalisib (PI-3 kinase inhibitor), and venetoclax (Bcl-2 inhibitor), has transformed the therapeutic and clinical landscape of CLL54. The preliminary data of ongoing trials that combine obinutuzumab with newer agents are summarized in Table 3. The use of ibrutinib has shown favorable clinical responses in naïve, relapsed/refractory CLL patients and those with unfavorable mutations55; keeping in mind that preclinical data suggest that ibrutinib might inhibit antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity which is a key function of CD20 mAb56. On the other hand, in vitro data have shown that targeting CLL with obinutuzumab is not affected by the presence of BCR signaling pathway inhibitors (e.g. ibrutinib and idelalisib)57,58. Preliminary data of a phase IB/II clinical trial of ibrutinib in combination with obinutuzumab showed that this regimen is safe, it is associated with favorable clinical and hematological responses 59. Currently, obinutuzumab is undergoing investigation in a phase II clinical trial in combination with ibrutinib (NCT02345863); and in other studies combined with idelalisib (NCT02445131) or venetoclax (NCT02242942).

Table 3.

Selected Trials of Obinituzumab and Other Agents

| Trials | Phase | Dose* (mg) | Number | Treatment Arms | AE’s | Best Overall Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher K et. al. 63 (CLL14 Trial) | III | O: 1000 mg V: 20–400 mg |

13 | O+V | Neutropenia: 66.7% (G 3/4: 58%) IRRs: 75% (G 3/4: 8%) |

ORR: 100% CR: 58% MRD 92% |

| Amaya-Chanaga CI et al. 59 | IB/II | O: 1000 mg I: 420 mg |

9 | O+I | Neutropenia: 33% (G 3/4: 22%) IRRs: 11% (G 3/4: 0) |

CR: 50% (N=1) PR:50% (N=1) |

| Von Tresckow J et al. 64 (CLL2-BIG trial) | II | O: 1000 mg I: 420 mg |

66 | O+I | Neutropenia: 19% (G 3/4: 14%) IRRs: 33% (G 3/4: 2%) |

ORR: 100% CR: 46% PR: 54 % |

| Cramer P. et al. 65 (CLL2-BAG Trial) | II | B: 70 mg/m2 O: 1000 mg V: 20–400 |

66 | B→O/V | Neutropenia: 11% IRRs: 9% |

ORR: 97% CR: 38% |

| Jain N et al. 66 (iFCG Trial) |

II |

FC O: 1000 mg I: 420 mg |

23 | iFCO | Neutropenia (G 3/4): 48% | ORR: 100% CR: 39% |

Abbreviations: O/G, obinutuzumab; V, venetoclax; I, ibrutinib; B, bendamustine; FC, fludarabine/cyclophosphamide; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; ORR, objective response rate; MRD, minimal residual disease; IRRs, infusion-related reactions.

Finally, emerging data suggest that obinutuzumab is cost effective. In patients with previously untreated CLL, the combination of obinutuzumab with chlorambucil was associated with an increase of 0.83 life years and 0.79 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) compared to ofatumumab 60. In another study in patients with CLL, obinutuzumab and chlorambucil was found to be cost-effective compared to rituximab and chlorambucil; ofatumumab with chlorambucil; or chlorambucil62. In patients with relapsed/refractory rituximab-based therapy follicular lymphoma, the use of obinutuzumab with bendamustine followed by obinutuzumab monotherapy compared to bendamustine monotherapy, was cost-effective by increasing QALYs 61.

In conclusion, obinutuzumab is a promising drug with activity against clinical B-cell LPDs. It appears to have higher potency than other anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. It is associated with a favorable toxicity profile, as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy. Results of ongoing clinical trials, especially in combination with novel agents are expected to determine the role of obinutuzumab, in an effort to optimize the therapeutic management of patients with CLL and other B-cell LPDs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Type I and II Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibodies

| Type I | Type II | |

|---|---|---|

| Drugs | Rituximab, Ofatumumab | Obinutuzumab |

| Fc modification | No | Yes |

| Glyco-engineered | No | Yes |

| ADCC | ↑↑ | ↑↑↑ |

| ADCP | ↑↑ | ↑↑↑ |

| CDC | ↑↑↑ | - |

| DCD | ↑ | ↑↑↑ |

Abbreviations: ADCC, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity; ADCP, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis; CDC, complement-dependent cytotoxicity; DCD, direct cell death; FC fragment crystallizable region

Drug Summary Box.

| Drug name | Obinutuzumab |

| Phase | III |

| Indication | In combination with chlorambucil for the treatment of patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia; and in combination with bendamustine followed by obinutuzumab monotherapy, for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma who relapsed after, or are refractory to, a rituximab-containing regimen. |

| Pharmacology description | Obinutuzumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets the CD20 antigen expressed on the surface of pre B- and mature B-lymphocytes. Upon binding to CD20, it mediates B-cell lysis through (1) engagement of immune effector cells, (2) by directly activating intracellular death signaling pathways (direct cell death), and/or (3) activation of the complement cascade. The immune effector cell mechanisms include antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis. |

| Route of administration | Intravenous |

| Pivotal trial(s) | [35] [44] |

Acknowledgments

Funding:

The authors are supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Grant No. P30CA016672

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- 1.Medhanie GA, Fedewa SA, Adissu H, et al. Cancer incidence profile in sub-Saharan African-born blacks in the United States: Similarities and differences with US-born non-Hispanic blacks. Cancer 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto JF, Goodman MT. Patterns of leukemia incidence in the United States by subtype and demographic characteristics, 1997–2002. Cancer causes & control : CCC 2008; 19(4): 379–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, et al. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. British journal of cancer 2011; 105(11): 1684–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez JA, Land KJ, McKenna RW. Leukemias, myeloma, and other lymphoreticular neoplasms. Cancer 1995; 75(1 Suppl): 381–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sant M, Allemani C, Tereanu C, et al. Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: results of the HAEMACARE project. Blood 2010; 116(19): 3724–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating MJ, O’Brien S, Albitar M, et al. Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(18): 4079–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tam CS, O’Brien S, Plunkett W, et al. Long-term results of first salvage treatment in CLL patients treated initially with FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab). Blood 2014; 124(20): 3059–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badoux XC, Keating MJ, Wang X, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemoimmunotherapy is highly effective treatment for relapsed patients with CLL. Blood 2011; 117(11): 3016–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson PA, Tam CS, O’Brien SM, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab treatment achieves long-term disease-free survival in IGHV-mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2016; 127(3): 303–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cazin B, Divine M, Lepretre S, et al. High efficacy with five days schedule of oral fludarabine phosphate and cyclophosphamide in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. British journal of haematology 2008; 143(1): 54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010; 376(9747): 1164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer K, Bahlo J, Fink AM, et al. Long-term remissions after FCR chemoimmunotherapy in previously untreated patients with CLL: updated results of the CLL8 trial. Blood 2016; 127(2): 208–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GAZYVA (obinutuzumab) Prescribing Information Revised 2013. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/125486s000lbl.pdf last accessed September 1, 2017.

- 14.GAZYVA (obinutuzumab) Prescribing Information Revised 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/125486s013lbl.pdf, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- 15.Gazyvaro Product Information. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002799/WC500171594.pdf last accessed September 1, 2017.

- 16.Polyak MJ, Li H, Shariat N, et al. CD20 homo-oligomers physically associate with the B cell antigen receptor. Dissociation upon receptor engagement and recruitment of phosphoproteins and calmodulin-binding proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry 2008; 283(27): 18545–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheson BD, Leonard JP. Monoclonal antibody therapy for B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The New England journal of medicine 2008; 359(6): 613–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartron G, Watier H. Obinutuzumab: what is there to learn from clinical trials? Blood 2017; 130(5): 581–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herter S, Herting F, Mundigl O, et al. Preclinical activity of the type II CD20 antibody GA101 (obinutuzumab) compared with rituximab and ofatumumab in vitro and in xenograft models. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2013; 12(10): 2031–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bologna L, Gotti E, Manganini M, et al. Mechanism of action of type II, glycoengineered, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody GA101 in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia whole blood assays in comparison with rituximab and alemtuzumab. Journal of immunology 2011; 186(6): 3762–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederfellner G, Lammens A, Mundigl O, et al. Epitope characterization and crystal structure of GA101 provide insights into the molecular basis for type I/II distinction of CD20 antibodies. Blood 2011; 118(2): 358–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu SD, Chalouni C, Young JC, et al. Afucosylated antibodies increase activation of FcgammaRIIIa-dependent signaling components to intensify processes promoting ADCC. Cancer immunology research 2015; 3(2): 173–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golay J, Da Roit F, Bologna L, et al. Glycoengineered CD20 antibody obinutuzumab activates neutrophils and mediates phagocytosis through CD16B more efficiently than rituximab. Blood 2013; 122(20): 3482–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mossner E, Brunker P, Moser S, et al. Increasing the efficacy of CD20 antibody therapy through the engineering of a new type II anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced direct and immune effector cell-mediated B-cell cytotoxicity. Blood 2010; 115(22): 4393–402. ** This article describes the development of GA101 as the first Fc-engineered, type II humanized IgG1 antibody against CD20 and it shows that relative to rituximab, GA101 has increased direct and immune effector cell-mediated cytotoxicity and exhibits superior activity in cellular assays and whole blood B-cell depletion assays. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein C, Lammens A, Schafer W, et al. Epitope interactions of monoclonal antibodies targeting CD20 and their relationship to functional properties. mAbs 2013; 5(1): 22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janas E, Priest R, Wilde JI, et al. Rituxan (anti-CD20 antibody)-induced translocation of CD20 into lipid rafts is crucial for calcium influx and apoptosis. Clinical and experimental immunology 2005; 139(3): 439–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polito L BM, Maiello S, Battelli MG, et al. Rituximab and other new anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treatment. EMJ Oncol. 2014;2:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Domagala A BM, Stachura J, Siernicka M, Mrowka P, Dwojak M, Pyrzynska B, Firczuk M and Winiarska M. Lysosomal disruption augments obinutuzumab-induced direct cell death. Blood 2016. 128:2766. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herting F, Friess T, Bader S, et al. Enhanced anti-tumor activity of the glycoengineered type II CD20 antibody obinutuzumab in combination with chemotherapy in xenograft models of human lymphoma. Leukemia & lymphoma 2014; 55(9): 2151–5160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalle S, Reslan L, Besseyre de Horts T, et al. Preclinical studies on the mechanism of action and the anti-lymphoma activity of the novel anti-CD20 antibody GA101. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2011; 10(1): 178–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cartron G, de Guibert S, Dilhuydy MS, et al. Obinutuzumab in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: final data from the phase 1/2 GAUGUIN study. Blood 2014; 124(14): 2196–202. * This study demonstrated the safety and efficacy of obinutuzumab monotherapy in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salles GA, Morschhauser F, Solal-Celigny P, et al. Obinutuzumab in patients with relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma: results from the phase II GAUGUIN study. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(23): 2920–6. * This study demonstrated the safety and efficacy of obinutuzumab monotherapy in relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radford J, Davies A, Cartron G, et al. Obinutuzumab plus CHOP or FC in relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma: results of the GAUDI study (BO21000). Blood 2013; 122(7): 1137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salles G, Morschhauser F, Lamy T, et al. Phase 1 study results of the type II glycoengineered humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody obinutuzumab (GA101) in B-cell lymphoma patients. Blood 2012; 119(22): 5126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. The New England journal of medicine 2014; 370(12): 1101–10. ** This phase 3, randomized trial demonstrated that combining an anti-CD20 antibody with chemotherapy improved outcomes in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. In this patient population, obinutuzumab was superior to rituximab when each was combined with chlorambucil. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogura M, Tobinai K, Hatake K, et al. Phase I study of obinutuzumab in Japanese patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer science 2013; 104(1): 105–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sehn LH, Assouline SE, Stewart DA, et al. A phase 1 study of obinutuzumab induction followed by 2 years of maintenance in patients with relapsed CD20-positive B-cell malignancies. Blood 2012; 119(22): 5118–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyer MJ GA, Díaz MG, Dreyling M, et al. Obinutuzumab in combination with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone) or bendamustine for the first-line treatment of follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Final results from the maintenance phase of the phase Ib GAUDI study. Blood 2014;124:1743–43. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown JR, O’Brien S, Kingsley CD, et al. Obinutuzumab plus fludarabine/cyclophosphamide or bendamustine in the initial therapy of CLL patients: the phase 1b GALTON trial. Blood 2015; 125(18): 2779–85. * This stydy demonstrated that obinutuzumab with either fludarabine/cyclophosphamide or bendamustine shows manageable toxicity and has promising activity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Byrd JC, Flynn JM, Kipps TJ, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of obinutuzumab monotherapy in symptomatic, previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2016; 127(1): 79–86. * This study demonstrated that although exploratory, an obinutuzumab dose-response relationship may exist, but its relevance to improving progression-free survival is unclear and requires further follow-up. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goede V FK, Bosch F, Follows G, et al. Updated Survival Analysis from the CLL11 Study: Obinutuzumab Versus Rituximab in Chemoimmunotherapy-Treated Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 2015; 126: 1733.26450950 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vitolo U, Trněný M, Belada, et al. Obinutuzumab or rituximab plus CHOP in patients with previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final results from an open-label, randomized phase 3 study (GOYA). American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; December 3–6, 2016; San Diego, CA: Abstr. 470. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcus RE DA, Ando K, et al. Obinutuzumab-based induction and maintenance prolongs progression-free survival in patients with previously untreated follicular lymphoma: primary results of the randomized phase 3 GALLIUM study; American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; San Diego, CA, 2016, Abstr. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sehn LH, Chua N, Mayer J, et al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2016; 17(8): 1081–93. ** This study demonstrated that obinutuzumab plus bendamustine followed by obinutuzumab maintenance has improved efficacy over bendamustine monotherapy in rituximab-refractory patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with manageable toxicity, and is a new treatment option for patients who have relapsed after or are no longer responding to rituximab-based therapy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLaughlin P, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Link BK, et al. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16(8): 2825–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen DT, Amess JA, Doughty H, et al. IDEC-C2B8 anti-CD20 (rituximab) immunotherapy in patients with low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and lymphoproliferative disorders: evaluation of response on 48 patients. European journal of haematology 1999; 62(2): 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Byrd JC, Murphy T, Howard RS, et al. Rituximab using a thrice weekly dosing schedule in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma demonstrates clinical activity and acceptable toxicity. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19(8): 2153–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Brien SM, Kantarjian H, Thomas DA, et al. Rituximab dose-escalation trial in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19(8): 2165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winkler U, Jensen M, Manzke O, et al. Cytokine-release syndrome in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and high lymphocyte counts after treatment with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab, IDEC-C2B8). Blood 1999; 94(7): 2217–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freeman CL, Morschhauser F, Sehn L, et al. Cytokine release in patients with CLL treated with obinutuzumab and possible relationship with infusion-related reactions. Blood 2015; 126(24): 2646–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freeman CL, Dixon M, Houghton R, et al. Role of CD20 expression and other pre-treatment risk factors in the development of infusion-related reactions in patients with CLL treated with obinutuzumab. Leukemia 2016; 30(8): 1763–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tam C, Kuss B, Opat S, et al. Management of patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with obinutuzumab and chlorambucil. Internal medicine journal 2017; 47 Suppl 4: 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stilgenbauer S IO, Woszczyk D, Renner C, et al. Safety and efficacy of obinutuzumab plus bendamustine in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: subgroup analysis of the GREEN study. Blood 2015. 126:493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cramer P, Hallek M, Eichhorst B. State-of-the-Art Treatment and Novel Agents in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Oncology research and treatment 2016; 39(1–2): 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naive and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood 2015; 125(16): 2497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kohrt HE, Sagiv-Barfi I, Rafiq S, et al. Ibrutinib antagonizes rituximab-dependent NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Blood 2014; 123(12): 1957–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yasuhiro T, Sawada W, Klein C, et al. Anti-tumor efficacy study of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, ONO/GS-4059, in combination with the glycoengineered type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody obinutuzumab demonstrates superior in vivo efficacy compared to ONO/GS-4059 in combination with rituximab. Leukemia & lymphoma 2017; 58(3): 699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cramer P, Langerbeins P, Hallek M. Combination of Targeted Drugs to Control Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Harnessing the power of new monoclonal antibodies in combination with ibrutinib. Cancer journal 2016; 22(1): 62–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amaya-Chanaga CI, Choi MY, Nguyen N, et al. A Phase Ib/II study of ibrutinib in combination with obinutuzumab as first-line treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia > 65 years old or with coexisting conditions. Blood 2016; 128: 2048. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reyes C, Gazauskas G, Becker U, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of obinutuzumab versus ofatumumab for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2014. 124:1324. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guzauskas GF, Masaquel A, Reyes C, et al. What is the cost-effectiveness of obinutuzumab plus bendamustine followed by obinutuzumab monotherapy for the treatment of follicular lymphoma patients who relapse after or are refractory to a rituximab-containing regimen in the US? Blood 2016. 128:3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blommestein HM, de Groot S, Aarts MJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of obinutuzumab for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in the Netherlands. Leukemia research 2016; 50: 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Fink AM, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2017; 129(19): 2702–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Von Tresckow J, Cramer P, Bahlo J, et al. CLL2-BIG - A novel treatment regimen of bendamustine followed by GA101 and ibrutinib followed by ibrutinib and GA101 maintenance in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of a phase II trial. Blood 2016; 128:640. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cramer P VT, Bahlo J, Robrecht S, et al. Bendamustine (B), followed by obinutuzumab (G) and venetoclax (A) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): CLL2 ‐BAG trial of the German CLL study group (GCLLSG). Hematological Oncology Volume 35, Issue Supplement S2 June 2017. Pages 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jain N TP, Burger J , Borthakur G , et al. Ibrutinib, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and obinutuzumab for previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with mutated IGHV and non-del (17p). J Clin Oncol 35, no. 15_suppl (May 2017) 7522–22. [Google Scholar]