Abstract

A hallmark of higher brain function is the ability to rapidly and flexibly adjust behavioral responses based on internal and external cues. Here, we examine the computational principles that allow decisions and actions to unfold flexibly in time. We adopt a dynamical systems perspective and outline how temporal flexibility in such a system can be achieved through manipulations of inputs and initial conditions. We then review evidence from experiments in non-human primates that support this interpretation. Finally, we explore the broader utility and limitations of the dynamical systems perspective as a general framework for addressing open questions related to the temporal control of movements, as well as in the domains of learning and sequence generation.

Keywords: Dynamical systems, flexible timing, sensorimotor control, learning, movement sequences, movement planning

Toward a deeper understanding of flexible timing

Temporal aspects of sensorimotor function are strikingly flexible. Humans can anticipate events based on single observations, deliberately control movement initiation time, and flexibly adjust the duration of their movements. Although temporal flexibility is a cardinal feature of sensorimotor behavior, we do not yet understand its underlying mechanisms.

Our most detailed understanding of the neurobiology of time in sensorimotor function comes from experiments in animal models. These experiments have revealed a great deal about how neural activity in various cortical and subcortical brain areas contribute to an animal’s overall ability to produce timed behaviors [1–3]. However, most traditional experiments have focused on relatively undemanding behavioral tasks that do not require deliberate, rapid, and flexible control of timed behavior (Box 1).

Box 1. Timing tasks that do not require flexibility.

Interval timing is typically discussed under the rubrics of sensory timing and motor timing. Sensory timing is concerned with the ability to measure an interval of time. Animal models of sensory timing typically use simple tasks that require the animal to make judgments about the duration of an interval, for example, by reporting the longer of two intervals [87,88]. Making binary judgments about the duration of an interval requires a process that can explicitly or implicitly track elapsed time, but it does not demand trial-by-trial flexibility; animals can decide straightforwardly by comparing elapsed time to a fixed decision criterion. Motor timing, on the other hand, is associated with the ability to produce a desired time interval. Traditional animal models of motor timing have also relied on relatively undemanding tasks that require the animal to respond after a fixed delay, either reflexively through conditioning, or voluntarily in anticipation of movements and/or reinforcements [87,89–96]. For example, in the classical eye-blink conditioning paradigm, over the course of a few hundred trials, rabbits and rats can be conditioned to a fixed delay between a conditioned and an unconditioned stimulus (e.g., tone and an air puff to the cornea) [94–96] but the behavior is reflexive and does not involve deliberate control.

Timing has also been studied in other behavioral domains. For example, in perceptual tasks, some studies have examined the temporal control of attention. A common paradigm is to experimentally control the hazard of time for an impending stimulus; i.e., the probability that an event is about to happen [97,98]. Temporal hazards modulate sensory neural responses and can help animals detect and/or discriminate stimuli more efficiently [99,100]. Similarly, temporal organization of trials, stimuli, and reinforcement schedule modulate neural responses in higher brain areas and enable animals to optimize reaction times and choice behavior in decision making tasks [19,101–105]. However, a common feature of these experiments is that the temporal aspects of behavior emerge and adapt slowly after repeated exposures and are relatively inflexible.

Our discussion pertains to the ability to exert deliberate and flexible control over the dynamics of latent and observable behavioral variables in accordance with explicit instructions, contextual cues, sensory measurements, and environmental feedback. A number of recent experiments in animal models have begun to exploit more sophisticated behavioral tasks to investigate the computational principles and neural mechanisms that underlie flexible sensorimotor timing [4–11]. Some of these studies [5,6] as well as a growing literature in models of flexible timing [12,13] have proposed that the neural basis of flexible timing may be most suitably studied using the mathematics of dynamical systems (see Glossary). The concept of dynamical systems has its origins in Newtonian mechanics that describes how interaction between objects and forces determine the movement of objects in space. The application of this framework to neurobiology of time seeks to explain how interactions among a network of recurrently interacting neurons and inputs they receive determine the evolution of patterns of neural activity in the brain. We develop this framework in a simple but telling example in which the brain flexibly controls the time to initiate a movement, and discuss its broader utility for flexible temporal control of movements, motor sequences, learning and adaptation.

A dynamical systems framework for neural population activity

One way to describe neural activity across a population of neurons is to depict their collective pattern of activity as a point in a coordinate system where each axis corresponds to the activity of one neuron. This coordinate system is referred to as the state space and the point representing neural activity is known as the neural state, or more succinctly, the state. For example, if we have three neurons, the state at a specific time is represented by a point in a three-dimensional state space. Within the state space, changes in the pattern of neural activity is depicted as movements of the neural state, and the path along which states evolve is called a neural trajectory.

The dynamical systems theory uses rigorous mathematics to explain how neural states evolve within the state space as a function of time. To capture the full diversity of activity patterns that a population of neurons can generate, one would need an extraordinarily complex model. An important step in understanding the relationship between neurobiological details and behaviorally-relevant computations is to build simplified models. A thorough discussion of how faithfully a model should reflect the neurobiological components of a neural population is an active line of research at the intersection of neuroscience and machine learning, and is beyond the scope of this manuscript (see [14]). Here, we make a number of judicious simplifying assumptions to discuss the key computational principles that govern flexible timing. See Box 2 for a full description of these assumptions.

Box 2. Dynamical systems model assumptions.

We assumed that the state of the system, X, can be completely defined in terms of the activity of the relevant neurons. In other words, we do not explicitly model various factors such as receptor density, the states of voltage- and calcium-dependent channels, or the varying kinetics of different types of neural signaling. We also assume that the evolution of neural state, X, can be formulated as follows:

In this equation, the derivative of the neural state with respect to time (dX/dt) is specified by the sum of two factors: 1) f(X), which accounts for how activity of the neurons in the system influence each other (i.e. synaptic weights and biophysical nonlinearities), and 2) U that reflects external inputs (i.e., inputs received from neurons not represented by X).

This formulation implicitly assumes that the effect of input can be separated from interactions among neurons. Specifically, we limit the interactions between f(X) and U to be additive. If this assumption were relaxed, the dynamics would be governed by the more general equation:

Such a formulation may be necessary to capture more complex types of neural signalling, such as neuromodulation. One might also have to expand the domain of X to include additional variables such as excitability or synaptic efficacy that various signaling pathways that we have not considered might influence more directly.

We also assume that the function f(X) does not directly depend on time. While this assumption may be permissible for understanding behaviors that require trial-by-trial flexibility [5,41,43–48], this may not be the case in general. For example, in many timing experiments, animals are instrumentally conditioned to repeatedly produce a single interval. In these situations, animals may develop highly stereotyped motor response patterns that are highly inflexible [33]. In other paradigms, animals are trained to adjust their timing behavior over blocks of trials to match new reward contingencies [106]. In these experiments, the behavior is typically non-stationary, and therefore it is conceivable that behavioral adjustments are mediated by changes in f(X).

Finally, we also assume that U has low temporal complexity. This assumption is motivated by the fact that tracking time is an internal process that does not rely on temporally complex external stimuli. Indeed, the dynamical systems perspective may be of little value if the evolution of neural states were dominated by a temporally complex input. For example, in early sensory areas such as the primary visual cortex, neurons may exhibit complex dynamics only because they are driven by a dynamic visual stimulus [107]. Accordingly, we assume that the complexity of the dynamics arises predominantly from f(X) and that the input U has low temporal complexity.

We assume that the behavior of a set of neurons that mediate flexible timing can be formulated as follows:

| Equation 1 |

In this equation, X represents the neural state. The time-independent function f(X) accounts for how activity of the neurons in the system influence each other (i.e. synaptic weights and biophysical nonlinearities). The input U reflects signals received from neurons not represented by including those driven by external stimuli. Equation 1 describes how f(X) and U together determine the time derivative of X, dX/dt, or how X changes as a function of time.

In Equation 1, the full range of dynamic behaviors that the system is capable of generating, which we refer to as the system’s latent dynamics, is specified by f(X) and U. With latent dynamics fully specified, the only additional information needed to predict the behavior of the system is its initial condition, X0, which specifies the neural state prior to generating a desired dynamic pattern of activity. Box 3 uses a simple example to illustrate how the behavior of a system may change depending on inputs and initial conditions.

Box 3. Initial conditions and inputs control dynamical system output.

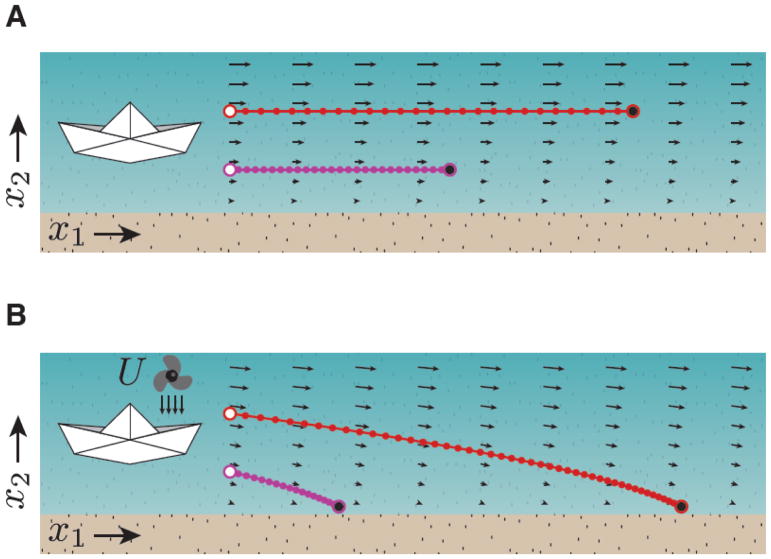

We use a simple example to build intuition on the influence of inputs and initial conditions on the behavior of a dynamical system. Consider sailing a paper boat in a stream where the strength of the current increases with distance from the shore. The horizontal arrows in Figure IA show the speed and direction the boat would move at any point on the stream (x1, x2). From a dynamical systems perspective, the arrows represent the latent dynamics of the system. Knowing the latent dynamics, the captain of the boat can control the sailing speed by choosing the appropriate initial sailing point along x2. As shown by the latent dynamics, larger x2 would lead to faster speed. The red and magenta show two distinct trajectories with two different speeds along which the state of the system can evolve. This example illustrates how choosing initial condition can exert control over the behavior of a dynamical system.

To understand the role of input, consider the same problem but this time, the captain wishes to use a portable fan to apply a tonic breeze on the boat’s port side (small downward arrows) and drive the boat toward the shore (Figure IB). In a dynamical system, this can be formulated as an external input, U. This input, which is independent of the state of the boat, alters the latent dynamics by adding a constant speed toward the bank at any given time (compare the arrows in Figure IA to those in IB). Now, the captain can choose an appropriate initial condition to control where the boat would make landfall (compare red and magenta). As demonstrated by this simple example, the boat’s trajectory can be controlled by making judicious choices about input and initial condition. These control principles can be applied more generally to dynamical systems established by network of neurons.

Figure I.

Effects of initial conditions and inputs on the position of a paper boat over time after being placed in a stream.

Application of dynamical systems framework to flexible timing

Humans and animals can track time mentally and deliberately control when to initiate a movement. How does the brain control movement initiation time? We can think of movement initiation as a change in neural activity from a “resting” state to an “action-triggering” state. Flexible motor timing then requires control of the process that determines how the system evolves from the resting to the action triggering state. Many studies found evidence of this process in various cortical and subcortical brain areas associated with sensorimotor function and motor planning [7,15–27]. An influential finding was that, while animals anticipate movement initiation, the activity of many neurons increased monotonically (i.e. ramping activity), and movement was initiated when the ramping activity reached a nearly fixed threshold. This ramp-to-threshold process is consistent with classical models of timing that assume neural circuits accumulate the ticks of a central clock, or pacemaker, initiating an action when the number of accumulated ticks reaches a predetermined threshold [28–30]. To support flexible timing, the slope of the ramping activity has to be adjusted on a trial-by-trial basis [4], consistent with a variant of the pacemaker-accumulator model in which the rate of the pacemaker is adjusted [29].

More recently, it was proposed that the brain relies on a larger diversity of neural signals than ramping to track elapsed time [12,31], and direct electrophysiological recordings revealed that ramping is one of a much wider range of response profiles that neurons exhibit in anticipation of movements [5,7,20]. Analysis of firing rates of neurons in the state space indicated that the brain adjusts the time it takes to reach terminal action-initiating state by controlling the speed with which neural states evolve along a neural trajectory [5,6,32]. Within the framework of dynamical systems (Equation 1), control of speed has a straightforward interpretation. The speed is the magnitude of the time derivative, dX/dt. Therefore, for a neural system to adjust speed, it should adjust the value of dX/dt. How can the system flexibly adjust dX/dt? According to Equation 2, dX/dt is fully determined by the input U and by f(X). Since f(X) accounts for synaptic weights and biophysical nonlinearities that typically do not change on a trial-by-trial basis, we assume that flexible and rapid control of timing does not rely on changes in f(X) (Box 2). With f(X) stationary, the only way to flexibly adjust speed is to change either U or the initial condition of the system, X0.

An important consideration for controlling speed through the input is whether or not the population of neurons under investigation is part of a larger closed-loop system. In closed-loop systems, the input, U, can become a function of the state of the system, X. For example, in many timing experiments, animals produce time intervals through continuous movements [33,34]. In these cases, neural circuits that produce the stream of motor commands receive inputs from concurrent reafferent signals (i.e., movement-related somatosensory and proprioceptive signals). This closed-loop interaction between internal state and external inputs makes it challenging to tease apart the relative contributions of internally generated dynamics from inputs. To avoid this complication, we have employed behavioral tasks in which animals produce time intervals by adjusting a motor plan prior to any overt movement. In this scenario, we assume X represents the population activity in premotor areas that control the motor plan and U represents an external input devoid of any reafferent signals. Speed may also be controlled flexibly by initial conditions (e.g., value of X at the beginning of a trial or a task epoch). Initial conditions do not directly modulate the time derivative of the state, but they exert their effect through X that leads to a concomitant change in the value of f(X).

Inputs and initial conditions support temporal flexibility

We highlight two studies that provide evidence that flexible control of timed behavior may indeed be achieved through adjustments of inputs and initial conditions. In the first [5], monkeys performed a "Cue, Set, Go" (CSG) task (Figure 1A). Animals initiated each trial by shifting their gaze to a central spot (fixation point) whose color provided explicit instruction ("Cue") about the desired interval. After a random delay, a stimulus flashed around the fixation point ("Set") marked the start of the interval. Animals had to initiate a saccade to a visual target either 800 or 1500 ms after Set ("Go") depending on the instruction. Importantly and unlike many previous experiments in rodents, the color of Cue varied at random on a trial-by-trial basis so that animals had to adjust their behavior based on an instruction at the beginning of each trial.

Figure 1. Flexible timing control through input adjustment.

A. Trial structure of CSG task. Animals aimed to produce either an 800 ms or 1,500 ms interval by making a saccade. Trials were randomly interleaved and were cued by the color of the fixation stimulus. A peripheral "Cue" indicated the saccadic target. After a random delay, a "Set" cue initiated the timing epoch, in which the animals’ production time was measured as the interval between Set and when the eye position reached the target ("Go"). When the produced time (tp) was generated within an acceptance window, the peripheral target turned green and the animal received a juice reward. B. The target regions in DMFC and thalamus indicated on a schematic of a parasagittal view of the monkey brain (gray). C. Population trajectories during timing epoch in DMFC (left) and thalamus (right). dimensionality reduction technique was implemented to identify the scaling subspace. The trajectories were sorted and colored according to instructed and produced intervals (see color bars, left) and projected onto their first three scaling components (SCs), which were ordered according to the degree of scaling within the population activity. D. Activity of the RNN model with an input cuing the correct tp. Network activity projected on the first three principal components across all trials. Different traces correspond to trials with different tp, following the same color scheme as the neural data. For each level of input, the network engenders a pair of initial and terminal fixed points (Circles: Finit and Fterminal). The input moves the fixed points within an "input" subspace. The corresponding trajectories for different intervals reside in a separate "recurrent" subspace. Panels C and D reproduced from [5].

Single neurons in premotor areas of the dorsomedial frontal cortex (DMFC; Figure 1B), a region implicated in initiation [24,35,36] and coordination [37–40] of movements, exhibited diverse and highly complex (e.g. non-monotonic) activity profiles. Despite this complexity however, responses of many neurons were temporally scaled with respect to the interval; i.e., the temporal profile of firing rates was compressed or stretched according to the produced interval. This temporal scaling can be evaluated across the population by examining the evolution of neural states in a state space representation. If response profiles of a group of neurons exhibit temporal scaling, it is expected that the corresponding neural trajectories would be spatially invariant, and would differ only in terms of the speed with which activity evolves along those trajectories. We therefore developed a technique that allowed us to extract the patterns of neural activity across the population that exhibited the greatest degree of temporal scaling (scaling subspace; Figure 1C). The structure of neural trajectories within this scaling subspace revealed that, as predicted, temporal flexibility was associated with an adjustment of speed of neural trajectories (Figure 1C, left).

Considering our assumption that temporal flexibility in CSG may be understood as adjustments of an input to a dynamical system, we examined the nature of thalamocortical signals that provide an input to DMFC. We found that thalamic neurons were characterized by an approximately tonic activity whose level was correlated with the Set-Go interval (Figure 1C, right). This observation provided evidence that a tonic input could control the speed of dynamics in DMFC.

To test this, we trained recurrent neural networks (RNN) to mimic behavioral performance on the CSG task. The RNNs received a tonic external input providing an explicit cue for the desired interval, and were trained to produce an output which reached a threshold at the time specified by the input (Figure 1D). Trajectories of the RNN population activity established an organization similar to those found in DMFC: different intervals were associated with adjustments of speed along similar neural trajectories. Neural trajectories associated with different intervals exhibited a form of similarity such that the relative position of each trajectory determined the speed at which its activity evolved (Figure 1D). In other words, intervals of different durations were generated by parallel neural trajectories moving through state space at different speeds [5,32].

This behavior can be readily understood in terms of the elements of a dynamical system [41,42]. A trained RNN establishes latent dynamics associated with a reservoir of speeds (i.e. different derivatives of the state). Within this reservoir, the input U drives the system along dimensions organized according to input magnitude (input subspace; Figure 1D) such that the corresponding f(x) could appropriately control the derivative of the state. This result, together with other studies exploiting RNNs to understand neural dynamics [5,41,43–48] suggest an important role for input in the flexible control of cortical dynamics.

To further test the generality of temporal flexibility in terms of inputs and initial conditions of a dynamical system, in a second study [6], we developed a context-dependent variant of a previous "Ready, Set, Go" (RSG) task [10] in which monkeys had to control saccade initiation times with a greater level of flexibility (Figure 2A). Animals had to initiate a saccade after a target interval, tt, whose duration was determined by the product of two variables, a sample interval, ts, that varied on a trial-by-trial basis, and a gain factor, g, that was either 1 or 1.5 depending on the context (i.e., tt=gts). Animals had to compute tt by combining information about the gain provided by the color of the fixation point with ts inferred from the interval between two flashes (“Ready” and “Set”). This modified RSG task thus provided a powerful testbed for assessing the role of inputs and initial conditions in flexible control of internally generated dynamics.

Figure 2. Speed control through initial conditions and input.

A. “Ready, Set, Go” task. On each trial, after a random delay following fixation, rectangular stimuli termed "Ready" and then "Set" were flashed. The time interval between Ready and Set demarcated a sample interval, ts. The monkey’s task was to generate a saccade (“Go”) to a visual target such that the interval between Set and Go (produced interval, tp) was equal to a target interval, tt, equal to ts multiplied by a gain factor, g (tt=gts). The animal had to perform the task in two behavioral contexts, one in which tt was equal to ts (g=1 context, bottom), and one in which tt was 50% longer than ts (g=1.5 context, top). The context was cued throughout the trial. B. Neural population activity recorded in DMFC activity in the Set-Go epoch. Data plotted using targeted dimensionality reduction. Top: neural trajectories within each context for different tp bins were ordered along an "initial condition" axis with different initial conditions and remained separate and ordered as they evolved toward the response along the "time" axis. Bottom: across the two contexts, neural trajectories were separated along an orthogonal dimension, which we illustrate as the "input" axis, without altering their relative organization as a function of tp. These features were consistent with control of speed through initial condition within context, and across context via a tonic (i.e. persistent and constant) external input. Filled circles depict states along each trajectory at a constant fraction of the trajectory length, illustrating speed differences across trajectories (circles are more closely spaced for the longer intervals associated with slower speed). C. Activity of RNNs, plotted as in B. Left: RNNs with a tonic input reproduced the key geometrical structure observed in the DMFC data, with trajectories separated according to initial condition and an orthogonal input axis. Right: In contrast, trajectories generated by a transient-input RNN were better described as coalescing towards a single structure parameterized by initial condition. Panels B and C reproduced from [6].

After verifying that monkeys were able to combine gain and interval on a trial by trial basis, we analyzed how these factors influenced the dynamics of neural activity in DMFC. Activity in the Set-Go epoch of the RSG task displayed qualitatively similar features to that in the CSG task. Neural trajectories were similar but advanced at different speeds (Figure 2B). This result provided additional evidence that the brain adjusts the derivative of firing rates to control movement initiation time (Figure 2B). However, unlike CSG in which speed had to be determined by a single cue, in RSG, speed had to be adjusted by two distinct factors, g and ts. Remarkably, this distinction was readily evident in the organization of neural trajectories (Figure 2B). The relative position of trajectories varied along two distinct dimensions in the state space, one associated with the duration of the interval (Figure 2B, top) and one associated with the value of the gain (Figure 2B, bottom). We therefore asked whether these two modes of flexibility could be understood in terms of adjustments of inputs and initial conditions.

We first focused on trajectories within each gain context. Like in CSG, these trajectories were organized systematically along a dimension associated with different speeds (Figure 2B, top), even though there was no external cue that could serve as an input U directly dependent on ts. Therefore, ts-dependent adjustment of speed in the Set-Go epoch must have resulted from a parametric control of initial conditions, X0, at the time of Set [49,50], which is controlled by the terminal point of the neural trajectory in the Ready-Set epoch [12,51]. In other words, the terminal point of activity in the Ready-Set epoch determines the initial condition, X0, of the neural trajectory in the ensuing Set-Go epoch. Changing X0 leads to changes in f(X0) and can thus adjust the derivative of the firing rates that corresponds to the speed of dynamics.

Across the two gain contexts, trajectories formed two similar structures that were displaced in state space along a dimension which was nearly orthogonal to the structure associated with each context (Figure 2B, bottom). Because the gain contexts were cued explicitly and persistently throughout the trial by the color of the fixation point, we reasoned that the effect of gain on neural structures might be due to adjustments of a gain-dependent input to DMFC. To test this possibility, we trained two families of RNNs to perform the RSG task, one in which the gain information was provided by a tonic input, and another in which the gain determined the network’s initial condition (i.e., transient gain input). The RNN with the tonic gain-dependent input displayed activity with strikingly similar structure to that of the DMFC data (Figure 2C), supporting our interpretation that flexibility with respect to gain is likely to be supported by a gain-dependent input. Together, these results indicate that various dimensions of temporal flexibility associated with movement initiation (e.g., with respect to ts and g) can be understood in terms of adjustments made to the initial conditions and/or inputs of a dynamical system.

In these two studies, we found that adjustments of movement initiation time were accompanied by changes to the speed at which internal states evolved over time. The larger insights however, came from analyzing these results within the framework of dynamical systems. Results indicated that patterns of activity are highly structured and evolve over time with a speed that is controlled by two complementary factors: the external input to neural system and the system’s initial conditions before the unfolding of dynamics associated with the control of movement initiation time.

Beyond movement initiation: learning, movement speed, and sequences

So far, our discussion has focused on the utility of dynamical systems for understanding flexible and deliberate control of movement initiation time. However, many other aspects of sensorimotor function demand temporal control. Therefore, an important question is whether the dynamical systems perspective could generate insights into the temporal control of behavior more generally. Here, we briefly explore the role of inputs and initial conditions in the context of a number of sensorimotor behaviors including learning of temporal statistics, control of overt movement speed, and the coordination of multiple movements through time.

Learning temporal statistics across contexts

The mechanisms that enable the brain to track time intervals are noisy [52,53]. To mitigate the uncertainty associated with noisy measurements of time, humans and animals rely on their prior beliefs of the temporal statistics they encounter, in accordance with Bayesian integration theory [10,54–56]. While humans can adapt their behavior to different temporal statistics [10,54–57], it usually takes time to update prior beliefs when the environmental statistics change [54,57,58]. Surprisingly, humans have difficulty simultaneously learning the temporal statistics of two randomly interleaved contexts even when the context is explicitly cued, for example by a color or sensory modality [59,60]. The same problem has been reported in other sensorimotor domains. For example, humans find it difficult to adapt to two randomly interleaved perturbations applied to the same movement [61–63], even when those perturbations are paired with explicit cues [64–66]. The key challenge appears to be an interference between the conditions that have to be learned.

To understand the source of this interference from the perspective of a dynamical system, let us examine the changes in Equation 1 that would allow the system to exhibit different behaviors for different contexts. Consider a situation in which the two contexts are not associated with different inputs or initial conditions. In this case, the only way to change the system’s latent dynamics and therefore its behavior, is to alter f(X). However, when the inputs and initial conditions are the same, the neural states associated with the two contexts would overlap in the state space. Since the same region of the state space cannot simultaneously represent two different latent dynamics [6,67], changes of f(X) needed to accommodate one context would naturally hinder learning associated with the other context. By inference, we conclude that the reason certain explicit cues do not facilitate simultaneous learning of multiple contexts is that the brain cannot use those cues to readily modulate either the input to of initial condition of the neural substrates that support learning and adaptation. Furthermore, a slower learning process in these situations may be a reflection of the brain finding ways to transform an ineffective cue to an appropriate input that would “untangle” the two contexts [67] and allow learning to proceed in parallel in two different regions of the state space.

Consistent with this viewpoint, learning of temporal statistics is improved when behavioral reports associated with different temporal contexts are made by different motor effectors [60] or are initiated from different positions [59]. A similar observation has been made for motor adaptation. Humans better adapt to distinct movement perturbations when those perturbations are coupled with different executed or planned “follow-through” movements [65,68]. How can these improvements be understood from the perspective of dynamical systems? As we discussed previously, adjustments to inputs U and initial conditions X0 can confer flexibility to the dynamics generated by a neural system. This indicates that altering either the motor effector or the initial movement position can serve as effective inputs and/or initial conditions for separating neural trajectories in the state space and facilitating the simultaneous learning of two contexts. The same logic could explain why different planned follow-throughs help humans learn multiple movement perturbations more effectively. The preparatory activity related to each follow-through might set up different initial conditions [49,50] and therefore lead to different paths through state space for identical initial movements. These examples extend the utility of the dynamical system perspective to studies of learning and suggest that control via inputs and initial conditions may facilitate simultaneous learning of different behavioral contexts.

Control of overt movement speed

Can the dynamical system perspective lend insight into how the brain might control the speed of overt actions? One complication for controlling the speed of movements is that the spatial and temporal aspects of movements tend to be encoded jointly [69], possibly by the same neural populations [70]. As a result, it may be difficult to change speed without changing movement trajectory. To keep the trajectory invariant, the system has to find a speed-modulating input U or set of initial conditions X0 that would not modulate neural activity in dimensions that control the spatial aspects of the movement. In other words, the effects of the control signals should be restricted to a subspace that is independent of the motor readout, also referred to as the "null" subspace [71]. In practice, it would perhaps suffice that modulation be restricted to task-irrelevant kinematic dimensions [72,73] such that the movement perturbations associated with speed do not adversely affect task performance.

In some cases, it may be useful to change the speed of an ongoing movement. The associated change in neural trajectory would require a modulating input U. However, determining the input needed to precisely and flexibly change the duration of an ongoing movement that is subject to sensory feedback may be challenging. As we previously noted, closing the sensorimotor loop results in U becoming dependent on X. Because movements create an internally-generated time-dependent, U augmenting U to flexibly adjust overt action would require knowledge of the precise latent dynamics in the vicinity of the movement trajectory. This raises an intriguing question. Can the nervous system flexibly adjust U during closed-loop control? For example, can the brain make on-the-fly adjustments to the speed of a movement? To do so, the system has to take into account the fact that the same change in U at different points in time could lead to very different changes of speed along the movement trajectory. Indeed, even for simple movements such as rotation of a wrist, instructions to change speed can cause complex changes in the speed profile [74]. These considerations suggest that humans may find it particularly challenging to control the duration of movements flexibly if the instruction is provided at random times after the movement is initiated. This may explain, for example, why expert soccer players rely heavily on early planning while executing penalty kicks [75]; inputs and initial conditions may be more controllable before the movement has initiated.

Planning and execution of movement sequences

Another consideration in temporal control of behavior is how actions are coordinated in time. Human speech, for example, requires the flexible arrangement of many motor patterns in time. Classical ideas about behavior suggest that the final state of one action can be used to trigger the initiation of the next action (i.e. f(X) is learned to transition seamlessly from the final state of one action to the initial state of the next action) [76]. However, this would lead to rigid action patterns incapable of replicating the flexibility of human behavior. More recently, it has been suggested that coordination of movement sequences may benefit from a flexible modular organization [77,78]. How might such modularity be instantiated in a dynamical system? In executing a single movement, physiological experiments indicate that changes in neural state related to planning occur in the null subspace [71]. This idea can readily be applied to action sequences: application of inputs to the motor system that modulate activity in this “null” subspace could be used to strategically set up the initial conditions for the next action in a sequence, allowing a seamless transition to one of many candidate actions. This predicts that changes in neural activity related to planning the next action would occur along dimensions in state space that are unrelated to the execution of the current action. Further, we expect to see a dichotomy in the control of actions with different effectors that are executed concomitantly and those that are organized into discrete chunks.

Actions that are executed concomitantly will require f(X) to control each effector jointly, resulting in the movement speed between separate effectors becoming yoked [80]. In contrast, discrete actions could potentially be planned in a sequence with different inputs or initial conditions, allowing independent speed control. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that recovery from timing perturbations is faster and more precise for discrete in comparison with continuous movements [81,82].

Concluding remarks

Mental functions such as those that involve temporal coordination, deliberation, and planning exhibit a great deal of flexibility. The mechanisms by which the brain controls such flexible behaviors remain poorly understood. A fundamental challenge is that these behaviors rely on functions at multiple scales, from the activity of individual neurons and specific cell types to coherent brain-wide interactions. This complexity brings into focus the need for a suitable level of abstraction at which one could hope to infer computational principles with a certain degree of invariance across tasks and conditions. Because networks of interacting neurons naturally form dynamical systems [70,83–86], we have adopted the perspective that computations related to the flexible control of behavior may be suitably characterized using the language of dynamical systems [5,12,13,31,41,43–48]. In this “computation-through-dynamics” framework, behaviorally relevant variables and computations are explained in terms of states and state transitions of a dynamical system established by recurrent interactions between neurons.

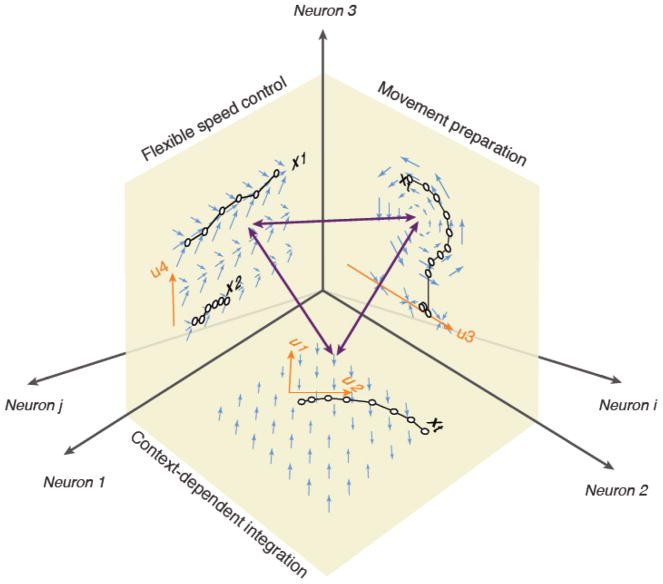

The main focus of our review was on flexible temporal control of behavior. We therefore used the dynamical systems perspective to ask how the nervous system might flexibly control temporal aspects of behavioral computations. The broader utility of the dynamical systems perspective depends on whether it could lend insight into the relationship between cortical function and behavior. This in turn, would depend on the degree to which one can parsimoniously characterize the dynamics generated by networks of cortical neurons in terms of contributions to recurrent dynamics, initial conditions and external inputs (see Outstanding Questions). This approach may prove insufficient for analyzing more complex and temporally extended behaviors such as thinking and speaking. Indeed, it is conceivable that for such complex behaviors, a more abstract representation may be more suitable for inferring invariant computational principles. However, our hope is that such complex behavior can be divided into invariant computational modules, and that each module is associated with the behavior of a dynamical system in a specific region of the state space (Figure 3). In this view, inputs and initial conditions may confer flexibility in a hierarchical fashion, with certain inputs selecting among various courses of action, certain others organizing the relevant actions within a sequence, and yet others, allowing each action to be performed flexibly. This would allow the dynamical systems perspective to serve not only as a means for understanding flexibility at the lowest level of hierarchy but also serve as a bridge between neurobiology and cognition.

Outstanding questions box.

What experimental or computational innovations are required to identify more direct neurobiological evidence for control via inputs and initial conditions, and what anatomical substrates might provide ideal targets? We have discussed recent work that leads us to hypothesize that flexible behavior is achieved by modifying inputs and initial conditions of a fixed recurrent system, but critical evaluation of this hypothesis will require experimental titration of the contributions of each component to behavior.

Can the dynamical systems perspective be used to link microscopic plasticity mechanisms identified at the level of single neurons to learning of latent dynamics that supports behaviorally-relevant computations? A crucial unknown is how the brain shapes the synaptic connections governing the intrinsic dynamical interactions, which we termed f(X).

How might our inferences change if we relax the constraints we have imposed in our dynamical model? For example, additional elements such as short-term plasticity could be incorporated into the state X and additional external influences such as neuromodulation may be incorporated into the input U. What can we hope to learn about computational principles by utilizing a more comprehensive model of neural function?

Figure 3. Subspaces could serve as modules enabling different computations.

The high dimensional neural state space is depicted through axes labeled ‘Neuron 1”, “Neuron 2”, etc. Three subspaces are shown as three orthogonal planes. Each plane represents a different computational module. The subspace spanned by Neuron 1 and 2 represents a dynamical system capable of performing context-dependent integration of information. In the example shown, the latent dynamics shown by blue arrows control the behavior of the network such that the state, X, integrates input u2 while ignoring another concurrent input u1. This computational scheme was suggested by a recent study of context-dependent decision making based on recordings from the population of neurons in the prefrontal cortex of monkeys [42]. The subspace spanned by Neuron 2 and 3 corresponds to a dynamical systems interpretation of the activity of populations of neurons in premotor and motor cortex responsible for the control of ballistic reach movements toward specific target locations [108]. The input u3 provided by a reach target sets the initial state of the system and the movement is associated with rotational dynamics governed by the system’s latent dynamics. According to this model, the muscle activity is derived from the state of the system, X, along a “movement-potent” subspace (not shown). The subspace spanned by Neuron 1 and 3 shows a system that uses input u4 to flexibly adjust the time derivative of the state (length of blue arrows), and therefore is capable of exerting flexible temporal control over the behavior [5]. The three double-sided arrows correspond to directions that have the capacity to select between different computations established by distinct subspaces. By depicting different sensorimotor and cognitive behaviors as latent dynamics within distinct subspaces, the figure aims to highlight a putative solution for how multiple computations might be hierarchically and/or modularly organized and flexibly selected from the state space established by higher brain circuits.

Highlights.

Flexible motor timing relies on controlling the speed at which neural activity evolves through state space

Setting inputs to and initial conditions of a network of cortical neurons could provide the means for selecting between multiple behaviorally-relevant computations

A dynamical systems perspective may provide a unified framework for understanding the computational principles of temporal flexibility in a wide range of sensorimotor behaviors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexandra Christine Ferguson for insightful discussions regarding dynamical systems. M.J. is supported by NIH (NINDS-NS078127), the Sloan Foundation, the Klingenstein Foundation, the Simons Foundation, the McKnight Foundation, the Center for Sensorimotor Neural Engineering, and the McGovern Institute. D.N. has received funding from the Rubicon grant by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (446-18-008) and from the European Union under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Grant (PredOpt 796577).

Glossary

- Closed-loop

A system whose output may influence its input.

- Dynamical system

A mathematical description of a system in which a set of differential equations determine how the state variables in the system change over time.

- Initial condition

The state of a dynamical system at a specific time after which the behavior of the system is analyzed. Here, we represent initial condition by the vector X0.

- Input

Factors not included in the description of a dynamical system that can influence the behavior of the system, represented by U.

- Latent dynamics

All the various ways in which inputs and interactions between the state variables of the system constrain the behavior of the system.

- Neural trajectory

A geometrical depiction of neural states visited over a specific interval of time through state space.

- Neural state

The value of all of the variables in a dynamical system, represented here by the vector X. Also referred to simply as the “state”

- Ramping activity

A monotonic change in the instantaneous firing rate of a neuron over time.

- Recurrent neural network (RNN)

A class of computational models comprised of interacting units. Each unit represents a neuron that can receive external inputs as well as inputs from other units in the network.

- Speed

The magnitude of the derivative of neural state as a function of time.

- State space

A Euclidean coordinate system where each axis corresponds to a state variable.

- Subspace

A subset of the full state space, in which the state can be described by a vector of reduced dimensionality.

- Time derivative

Rate of change as a function of time, represented here by the operator d/dt.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mauk MD, Buonomano DV. The neural basis of temporal processing. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:307–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finnerty GT, et al. Time in Cortical Circuits. J Neurosci. 2015;35:13912–13916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2654-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merchant H, et al. Neural basis of the perception and estimation of time. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2013;36:313–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062012-170349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jazayeri M, Shadlen MN. A Neural Mechanism for Sensing and Reproducing a Time Interval. Curr Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, et al. Flexible timing by temporal scaling of cortical responses. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:102–110. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0028-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remington ED, et al. Flexible Sensorimotor Computations through Rapid Reconfiguration of Cortical Dynamics. Neuron. 2018;98:1005–1019e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merchant H, et al. Measuring time with different neural chronometers during a synchronization-continuation task. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19784–19789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112933108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeya R, et al. Predictive and tempo-flexible synchronization to a visual metronome in monkeys. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6127. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06417-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohmae S, et al. Temporally specific sensory signals for the detection of stimulus omission in the primate deep cerebellar nuclei. J Neurosci. 2013;33:15432–15441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1698-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jazayeri M, Shadlen MN. A Neural Mechanism for Sensing and Reproducing a Time Interval. Curr Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García-Garibay O, et al. Monkeys Share the Human Ability to Internally Maintain a Temporal Rhythm. Front Psychol. 2016:7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karmarkar UR, Buonomano DV. Timing in the absence of clocks: encoding time in neural network states. Neuron. 2007;53:427–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laje R, Buonomano DV. Robust timing and motor patterns by taming chaos in recurrent neural networks. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:925–933. doi: 10.1038/nn.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jazayeri M, Afraz A. Navigating the Neural Space in Search of the Neural Code. Neuron. 2017;93:1003–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romo R, Schultz W. Role of primate basal ganglia and frontal cortex in the internal generation of movements. III Neuronal activity in the supplementary motor area. Exp Brain Res. 1992;91:396–407. doi: 10.1007/BF00227836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romo R, Schultz W. Neuronal activity preceding self-initiated or externally timed arm movements in area 6 of monkey cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1987;67:656–662. doi: 10.1007/BF00247297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schultz W, Romo R. Role of primate basal ganglia and frontal cortex in the internal generation of movements. I Preparatory activity in the anterior striatum. Exp Brain Res. 1992;91:363–384. doi: 10.1007/BF00227834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanes DP, Schall JD. Neural control of voluntary movement initiation. Science. 1996;274:427–430. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roitman JD, Shadlen MN. Response of neurons in the lateral intraparietal area during a combined visual discrimination reaction time task. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9475–9489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09475.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami M, et al. Neural antecedents of self-initiated actions in secondary motor cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1574–1582. doi: 10.1038/nn.3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maimon G, Assad JA. A cognitive signal for the proactive timing of action in macaque LIP. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:948–955. doi: 10.1038/nn1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komura Y, et al. Retrospective and prospective coding for predicted reward in the sensory thalamus. Nature. 2001;412:546–549. doi: 10.1038/35087595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuphorn V, et al. Role of supplementary eye field in saccade initiation: executive, not direct, control. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:801–816. doi: 10.1152/jn.00221.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okano K, Tanji J. Neuronal activities in the primate motor fields of the agranular frontal cortex preceding visually triggered and self-paced movement. Exp Brain Res. 1987;66:155–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00236211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen TW, et al. A Map of Anticipatory Activity in Mouse Motor Cortex. Neuron. 2017;94:866–879e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider BA, Ghose GM. Temporal production signals in parietal cortex. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunimatsu J, et al. Different contributions of preparatory activity in the basal ganglia and cerebellum for self-timing. Elife. 2018:7. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Treisman M. Temporal discrimination and the indifference interval: Implications for a model of the“ internal clock. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied. 1963;77:1. doi: 10.1037/h0093864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Killeen PR, Fetterman JG. A behavioral theory of timing. Psychol Rev. 1988;95:274–295. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.95.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meck WH. Neuropharmacology of timing and time perception. Cognitive Brain Research. 1996;3:227–242. doi: 10.1016/0926-6410(96)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buonomano DV, Maass W. State-dependent computations: spatiotemporal processing in cortical networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:113–125. doi: 10.1038/nrn2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shinomoto S, et al. Deciphering elapsed time and predicting action timing from neuronal population signals. Front Comput Neurosci. 2011;5:29. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2011.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawai R, et al. Motor cortex is required for learning but not for executing a motor skill. Neuron. 2015;86:800–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gouvêa TS, et al. Ongoing behavior predicts perceptual report of interval duration. Front Neurorobot. 2014;8:10. doi: 10.3389/fnbot.2014.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunimatsu J, Tanaka M. Alteration of the timing of self-initiated but not reactive saccades by electrical stimulation in the supplementary eye field. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;36:3258–3268. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fried I, et al. Functional organization of human supplementary motor cortex studied by electrical stimulation. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3656–3666. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03656.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis PA, et al. Brain activity correlates differentially with increasing temporal complexity of rhythms during initialisation, synchronisation, and continuation phases of paced finger tapping. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:1301–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shima K, Tanji J. Neuronal activity in the supplementary and presupplementary motor areas for temporal organization of multiple movements. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:2148–2160. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.4.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isoda M, Hikosaka O. Switching from automatic to controlled action by monkey medial frontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:240–248. doi: 10.1038/nn1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu X, et al. A neural correlate of oculomotor sequences in supplementary eye field. Neuron. 2002;34:317–325. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sussillo D, Barak O. Opening the black box: low-dimensional dynamics in high-dimensional recurrent neural networks. Neural Comput. 2013;25:626–649. doi: 10.1162/NECO_a_00409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mante V, et al. Context-dependent computation by recurrent dynamics in prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2013;503:78–84. doi: 10.1038/nature12742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mante V, et al. Context-dependent computation by recurrent dynamics in prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2013;503:78–84. doi: 10.1038/nature12742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sussillo D, et al. A neural network that finds a naturalistic solution for the production of muscle activity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1025–1033. doi: 10.1038/nn.4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hennequin G, et al. Optimal control of transient dynamics in balanced networks supports generation of complex movements. Neuron. 2014;82:1394–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaisangmongkon W, et al. Computing by Robust Transience: How the Fronto-Parietal Network Performs Sequential, Category-Based Decisions. Neuron. 2017;93:1504–1517e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song HF, et al. Training Excitatory-Inhibitory Recurrent Neural Networks for Cognitive Tasks: A Simple and Flexible Framework. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1004792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rajan K, et al. Stimulus-dependent suppression of chaos in recurrent neural networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2010;82:011903. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.011903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Churchland MM, et al. Cortical preparatory activity: representation of movement or first cog in a dynamical machine? Neuron. 2010;68:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Churchland MM, et al. Neural population dynamics during reaching. Nature. 2012;487:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature11129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gouvêa TS, et al. Striatal dynamics explain duration judgments. ELife. 2015;4:e11386. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malapani C, Fairhurst S. Scalar Timing in Animals and Humans. Learn Motiv. 2002;33:156–176. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibbon J. Scalar expectancy theory and Weber’s law in animal timing. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:279. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyazaki M, et al. Testing Bayesian models of human coincidence timing. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:395–399. doi: 10.1152/jn.01168.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jazayeri M, Shadlen MN. Temporal context calibrates interval timing. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1020–1026. doi: 10.1038/nn.2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Acerbi L, et al. Internal representations of temporal statistics and feedback calibrate motor-sensory interval timing. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Narain D, et al. A cerebellar mechanism for learning prior distributions of time intervals. Nat Commun. 2018;9:469. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02516-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Narain D, et al. Sensorimotor priors in nonstationary environments. J Neurophysiol. 2013;109:1259–1267. doi: 10.1152/jn.00605.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagai Y, et al. Acquisition of multiple prior distributions in tactile temporal order judgment. Frontiers in. 2012 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00276. at < http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc3418635/>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Roach NW, et al. Generalization of prior information for rapid Bayesian time estimation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:412–417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610706114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karniel A, Mussa-Ivaldi FA. Does the motor control system use multiple models and context switching to cope with a variable environment? Exp Brain Res. 2002;143:520–524. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brashers-Krug T, et al. Consolidation in human motor memory. Nature. 1996;382:252–255. doi: 10.1038/382252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caithness G, et al. Failure to consolidate the consolidation theory of learning for sensorimotor adaptation tasks. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8662–8671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2214-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cothros N, et al. Visual cues signaling object grasp reduce interference in motor learning. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:2112–2120. doi: 10.1152/jn.00493.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Howard IS, et al. The value of the follow-through derives from motor learning depending on future actions. Curr Biol. 2015;25:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Howard IS, et al. Gone in 0.6 seconds: the encoding of motor memories depends on recent sensorimotor states. J Neurosci. 2012;32:12756–12768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5909-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Russo AA, et al. Motor Cortex Embeds Muscle-like Commands in an Untangled Population Response. Neuron. 2018;97:953–966e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sheahan HR, et al. Motor Planning, Not Execution, Separates Motor Memories. Neuron. 2016;92:773–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Conditt MA, Mussa-Ivaldi FA. Central representation of time during motor learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11625–11630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shenoy KV, et al. Cortical control of arm movements: a dynamical systems perspective. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2013;36:337–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaufman MT, et al. Cortical activity in the null space: permitting preparation without movement. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:440–448. doi: 10.1038/nn.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Todorov E, Jordan MI. Optimal feedback control as a theory of motor coordination. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1226–1235. doi: 10.1038/nn963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scholz JP, Schöner G. The uncontrolled manifold concept: identifying control variables for a functional task. Exp Brain Res. 1999;126:289–306. doi: 10.1007/s002210050738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hoffman DS, Strick PL. Step-tracking movements of the wrist in humans. I Kinematic analysis. J Neurosci. 1986;6:3309–3318. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-11-03309.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van der Kamp J. A field simulation study of the effectiveness of penalty kick strategies in soccer: late alterations of kick direction increase errors and reduce accuracy. J Sports Sci. 2006;24:467–477. doi: 10.1080/02640410500190841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sherrington CS. CUP Archive. 1966. The Integrative Action of the Nervous System. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kornysheva K. Encoding Temporal Features of Skilled Movements—What, Whether and How? In: Laczko J, Latash ML, editors. Progress in Motor Control: Theories and Translations. Springer International Publishing; 2016. pp. 35–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Diedrichsen J, Kornysheva K. Motor skill learning between selection and execution. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Diedrichsen J, et al. Dissociating timing and coordination as functions of the cerebellum. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:6291–6301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0061-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Elliott MT, et al. Being discrete helps keep to the beat. Exp Brain Res. 2009;192:731–737. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1646-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Repp BH, Steinman SR. Simultaneous event-based and emergent timing: synchronization, continuation, and phase correction. J Mot Behav. 2010;42:111–126. doi: 10.1080/00222890903566418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hopfield JJ. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1982;79:2554–2558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fetz EE. Are movement parameters recognizably coded in the activity of single neurons? Behav Brain Sci. 1992 doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00072599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang XJ. Probabilistic decision making by slow reverberation in cortical circuits. Neuron. 2002;36:955–968. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Izhikevich EM. Dynamical Systems in Neuroscience. MIT Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mello GBM, et al. A scalable population code for time in the striatum. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1113–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leon MI, Shadlen MN. Representation of time by neurons in the posterior parietal cortex of the macaque. Neuron. 2003;38:317–327. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Matell MS, et al. Interval timing and the encoding of signal duration by ensembles of cortical and striatal neurons. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:760–773. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bakhurin KI, et al. Differential Encoding of Time by Prefrontal and Striatal Network Dynamics. J Neurosci. 2017;37:854–870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1789-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Namboodiri VMK, et al. Visually Cued Action Timing in the Primary Visual Cortex. Neuron. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shuler MG, Bear MF. Reward timing in the primary visual cortex. Science. 2006;311:1606–1609. doi: 10.1126/science.1123513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schultz W, et al. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McCormick DA, Thompson RF. Neuronal responses of the rabbit cerebellum during acquisition and performance of a classically conditioned nictitating membrane-eyelid response. J Neurosci. 1984;4:2811–2822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-11-02811.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Steinmetz JE, et al. Classical conditioning in rabbits using pontine nucleus stimulation as a conditioned stimulus and inferior olive stimulation as an unconditioned stimulus. Synapse. 1989;3:225–233. doi: 10.1002/syn.890030308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.ten Brinke MM, et al. Evolving Models of Pavlovian Conditioning: Cerebellar Cortical Dynamics in Awake Behaving Mice. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1977–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Luce RD. Response Times: Their Role in Inferring Elementary Mental Organization. Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nobre A, et al. The hazards of time. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ghose GM, Maunsell JHR. Attentional modulation in visual cortex depends on task timing. Nature. 2002;419:616–620. doi: 10.1038/nature01057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jaramillo S, Zador AM. The auditory cortex mediates the perceptual effects of acoustic temporal expectation. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:246–251. doi: 10.1038/nn.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Riehle A, et al. Spike synchronization and rate modulation differentially involved in motor cortical function. Science. 1997;278:1950–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Janssen P, Shadlen MN. A representation of the hazard rate of elapsed time in macaque area LIP. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:234–241. doi: 10.1038/nn1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shadlen MN, Newsome WT. Motion perception: seeing and deciding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:628–633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hanks T, et al. A neural mechanism of speed-accuracy tradeoff in macaque area LIP. Elife. 2014:3. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brody CD, et al. Timing and neural encoding of somatosensory parametric working memory in macaque prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:1196–1207. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Xu M, et al. Representation of interval timing by temporally scalable firing patterns in rat prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:480–485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321314111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Seely JS, et al. Tensor Analysis Reveals Distinct Population Structure that Parallels the Different Computational Roles of Areas M1 and V1. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1005164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Churchland MM, et al. Neural population dynamics during reaching. Nature. 2012;487:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature11129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]