Abstract

Background:

Promotion of positive deviant behaviors (PDBs) can be crucial to bring sustainable change as these behaviors are likely to be affordable and acceptable by the wider community.

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to assess if any PDBs exist among poorly resourced rural mothers with young children near Vadodara.

Materials and Methods:

Mothers of children <5 years (n = 160) were enrolled from four rural clusters near Vadodara based on their current growth status (weight-for-age) and were categorized as PD (n = 65) and negative deviant (ND; n = 95), as per the WHO Anthro Software. Personal interviews were conducted through household (HH) visits using a semistructured questionnaire. Data were elicited on HH socioeconomic status, infant and young child feeding practices, diet pattern, and hygiene–sanitation practices. HH dietary diversity score was calculated individually after collecting data through food frequency questionnaire.

Results:

Mothers had several significant PDBs (P < 0.05), PD group vs. ND group, less use prelacteals to children (53% vs. 71%) and had more exclusive breastfeeding rates (44% vs. 26%), provided cleaner clothing to children (52% vs. 28%), had sufficient intra-HH food distribution (30% vs. 18%), and scored better in dietary diversity at HH level (52% vs. 28%).

Conclusions:

PDBs and normal growth patterns do exist in poorly resourced areas, and these mothers can be used as “change agents” by the practicing pediatricians of rural communities for improving child health and nutrition.

Keywords: Change agents, child feeding, positive deviant behaviors, undernutrition, young children

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, there are several strategies and attempts that are being made to change the scenario of childhood undernutrition (162 million under 5 years were stunted, 52 million were severely wasted according to global nutrition report 2016). The outcome of these strategies varies from region to region and from various setups (urban, rural, or tribal) depending on the cultural practices of the community, especially their EMIC views. UNICEF (2013) reported that irrespective of the regions rural people in all over the world are much more affected by malnutrition than urban people. According to RSOC (Rapid Survey of Children) 2013–2014, in Gujarat, one of the most economically strong states of India, was still a cause of alarm, as 33.5% are underweight, 41.8% are stunted, and 18.7% are wasted.

Several reports have identified inadequate feeding practices, poor hygiene and sanitation practices, poor utilization of resources, and incorrect dietary pattern as some significant reasons for the poor nutritional status of the children in India.[1,2,3] However, amidst these poor habits and customs, there are also a few “deviant” individuals whose uncommon behaviors or practices enable them to outperform their neighbors with whom they share the same resources, and identification of them can be crucial to bring a sustainable change as their behaviors are likely to be affordable and acceptable by the wider community.[4] Positive deviance is a way of addressing childhood malnutrition by learning from scaling up what is working rather than what is not working,[5] to develop policies and programs that help transfer positive practices to the malnourished.[6]

There is a dearth of data on positive deviant behaviors among mothers of poorly resourced rural communities and its relationship with birth outcomes. The present study aimed to compare the positive deviant behaviors (PDBs) among poorly resourced rural households (HHs) of <5-year-old normal weight-for-age (WAZ >-2 standard deviation [SD]) children with those of HHs having undernourished children (WAZ ≤-2 SD) in the same age group (the WHO classification, 2010) in Western India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting and participants

This was an exploratory study, wherein four clusters with similar cultural backgrounds were purposively selected from a block of rural Vadodara, Western India. All HHs with children <5 years were enrolled with the help of the local government's Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS)-run Anganwadi center (n = 160).

Categorization of positive deviant/negative deviant based on anthropometric assessments

Anthropometric indices of the children (weight and height) were collected using standard procedures (WHO 2006). WAZ of the children was computed using the WHO Anthro software (2010), and based on their Z–scores, they were categorized into two groups: Group I with HHs having normal children (WAZ >-2 SD), named as positively deviant group and Group II with HHs having undernourished children (WAZ ≤-2 SD), named as negatively deviant group.

Household practices related to child health and nutrition

In-depth interviews at HH level were conducted to understand the socioeconomic status, age-specific infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices, HH diet pattern, and hygiene and sanitation practices as per the guidelines by the World Health Organization using semistructured questionnaire, focus group discussion, and direct observation.

Household dietary diversity score calculation

HH dietary diversity was estimated by a food frequency questionnaire which included a list of common Western Indian foods in groups of 11 (cereals, pulses and legumes, roots and tubers, green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, fruits, nuts and oilseeds, milk and milk products, nonvegetarian foods, fats and oil, and sugar). Consumption patterns were recorded based on their intakes (daily, weekly, fortnightly, monthly, occasional, or seasonal). Based on the data, HH Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) was calculated for each mother–child pair using a revised version of FAO guidelines,[7] wherein the households (HHs) which consumed half or more than half of the foods frequently in each food group scored as 1 and others scored as 0. The HHSs which had a HDDS ≥4 (i.e., consumption of four or more food groups per day) were considered positive and HHs with a score <4 were grouped as negative.

Data management and analysis

All data were entered in Microsoft Excel 2010 and analyzed using statistical software (SPSS23), whereas anthropometric data were calculated at the WHO Anthro software for WAZ analysis. Comparison between PD and ND groups was done using Chi-square test.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Food and Nutrition Department of the University (Approval No: IECHR/2015/16). Local community leaders were informed about the aim and procedures of the study. All the study participants gave their verbal consent to participate after the study objectives were explained to them.

RESULTS

Categorization of positive deviant/negative deviant groups based on anthropometric indices

Among 160 children, only 40% (n = 65) were normal as per (WAZ >-2 SD) and categorized as PD group, and 60% (n = 95) were undernourished children (WAZ <-2 SD) and categorized as negative deviant group (ND group).

Birth weight and age of positive deviant/negative deviant groups

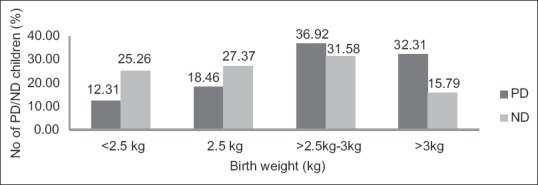

Birth weight was a major predictor of PD children (only 12% were <2.5 kg at birth vs. 25% LBW in ND group) [Figure 1], which corroborates with the findings that limited resources in poor communities may lead to chronic undernutrition during pregnancy and may result in poor birth outcomes.

Figure 1.

Birth weight versus child undernutrition (P < 0.05)*

In the ND group, 54.73% were >2 years versus 45.25% who were <2 years, while 6.31% were <6 months of age indicating the onset of undernourishment due to chronic energy deprivation. In the PD group, 40% were >2 years and a majority of 60% were <2 years [Table 1], revealing that undernutrition rate is higher among older children who do not depend on breastfeeding anymore and who require diversified diet and healthy diet pattern.

Table 1.

Infant and young child feeding practices of mothers having <5 year-old-children: Comparing positive deviant with negative deviant children

Socioeconomic status of positive deviant/negative deviant groups

Result reveals that among 65 PD children 53.8% were boys as compared to 50.5% in ND group, which indicates that undernutrition was prevalent in both the genders. Type of family had no positive influence on nutritional status of children as almost equal percentage of children belonged to joint family (69% PD and 68% ND). However, children from the family having 5 or <5 members were more prone to be malnourished (ND, 47.3%). Although the percentage of illiterate parents was more among ND children (11.5% mothers and 9.4% fathers) than PD children (9.2% mothers and 4.6% fathers), parent's educational status had no significant correlation with child undernutrition in the present study. Percentage of unemployed fathers was higher among ND. There was also poor status of agricultural practices in the area due to pollution caused by nearby industries which deteriorated the soil quality and resulted in less family income due to agriculture and indirectly leading to food insecurity and poor child nutrition. Family income of majority (61%) of ND children was ≤5000 rupees as compared to 47% PD children, indicating that family income can contribute to better nutritional status of the child as it increases the affordability of nutritious food.

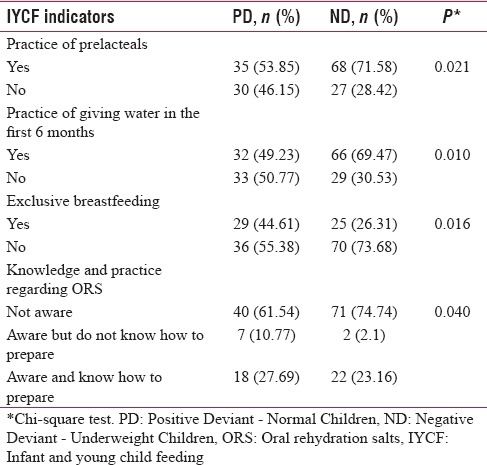

Child feeding practices of positive deviant/negative deviant groups

Among 65 PD children, 73.8% were initiated breastfeeding within 1 day after birth compared to 65.2% ND children [Table 1]. Although the incidence of colostrum feeding was higher among ND children (68.42% ND and 61.5% PD), practice of giving prelacteals (P < 0.05), water (P < 0.01), and top milk within the first 6 months was higher among ND children (71.5%, 69.4%, and 20%, respectively) compared to PD children (53.8%, 49.2%, and 13.8%, respectively). ND mother said – “I breastfed the child for exclusive breastfeeding practice within the first 6 months after birth was significantly (P < 0.05) higher among PD children (44.6% PD, 26.3% ND).” This result signifies that even though initial child feeding practices were followed as per standard guidelines, child can still become undernourished at a later age if other important positive child feeding behaviors such as exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) (not providing any kind of prelacteals water or food) for the first 6 months are not practiced appropriately.

Other child feeding practices such as continued breastfeeding up to 2 years, breastfeeding during illness, and practice of initiation of complementary feeding after 6 months were satisfactory for both PD and ND groups, and packaged food consumption was higher among both the groups. Among 160 children, mothers of 74.7% ND children were not at all aware of oral rehydration salt (ORS) treatment compared to 61.5% PD children (P < 0.05). Therefore, proper knowledge regarding ORSs and its practice during diarrheal infection can create a difference in child nutrition as incidence of frequent diarrheal infection leads to weight reduction and poor nutritional status.

Household dietary pattern of positive deviant/negative deviant groups

There was a significant difference observed (P < 0.05) in intra-HH food distribution and HH dietary diversity. Only men were fed well in the majority of ND HHs (PD 4.61% and ND 11.5%). Consumption of breakfast was poor in both PD and ND groups as only tea or very little snacks were consumed in the majority of the HHs. Four meals were consumed in higher percentage of PD HHs (PD 30.7% and ND 22%). HDDS was significantly correlated (P < 0.01) with child undernutrition as higher percentage of PD children (52.3%) scored positive DDS compared to ND children (28.4%).

Hygiene and sanitation practices of positive deviant/negative deviant groups

As regards hygiene and sanitation practices, significant difference (P < 0.01) was observed in case of cleanliness of clothes. Clothes were dirty (42%) and very dirty (25%) for majority of ND children as compared to PD children (30.7% and 16.9%, respectively). Practice of hand wash with soap during food handling (PD 49% and ND 35%) and presence of sanitary latrine with water facility (PD 29% and ND 17%) were higher among PD children. Clean nails were observed among 46% PD children as compared to only 31% ND children. This result reveals that hygiene and sanitation practices may affect child undernutrition, and in the present study cleanliness of clothes significantly contributing child nutritional status and hence need to be promoted through PD mothers.

DISCUSSION

Our study highlights several PDB in these marginalized communities, indicating that amidst the poor resources, these “deviant” practices such as desirable IYCF behaviors, especially EBF practices, no practice of prelacteals, no practice of giving water in the first 6 months, and knowledge and practice of ORS treatment during diarrheal infections exist leading to normal growth patterns of children. Intra-HH food distribution, HH dietary diversity, and clean clothing were some other factors identified which are likely to have contributed to the better nutritional status (higher WAZ) seen in PD children.

Previous studies in rural India, in villages of UP,[4] West Bengal,[8] and Tamil Nadu[9] have stated that positive deviance and normal growth of children were enhanced under conditions of small family size <5, parity below 3, family support to mother, timely initiation of breastfeeding, and higher frequency of breastfeeding. Studies in urban slums have indicated HH factors such as smaller family size, higher maternal literacy, lower parity of child, better environmental hygiene, fewer morbidity episodes (mainly diarrhea), and desirable IYCF practices such as frequent breastfeeding, timely initiation of complementary food, active feeding, and giving foods of thicker consistency.[10] Thus, whether rural or urban, several “deviant” behaviors exist.[11]

Another important factor recorded in our study was adequate dietary diversity score at HH level which is a major factor to affect child nutrition in poor communities. Therefore, efforts should also be made to improve the variety of staple food production and use of locally available indigenous foods or their biofortification[12] along with nutrition communication.[13] Nutrition education based on positive deviance approach and supplementary nutrition helps to improve the nutritional status of the Anganwadi children[14] and PDA could be a community-based solution to improve child's nutritional status. Nutritional surveys are needed to identify most significant malnutrition determinants to see adoption of new behaviors and sustainability of outcomes,[15] and such promotion of indigenous positive correlates of child growth and community wisdom through people who promote positive practices can be done.[16,17]

At programmatic level, grassroot-level workers of government programs such as ICDS need to focus on adolescent girls, pregnant, and lactating mothers and make regular home visits. Services such as iron–folic acid tablet distribution and antenatal care of pregnant mothers were available, but still low birth weight rate was quite high in the study area.[18] PDBs regarding health-care practices and ICDS utilization were not assessed in the present study, which is one of the limitations of the study and is highly recommended in future studies as such evaluations can identify gaps and plan nutrition health education.[19]

CONCLUSIONS

Practicing health-care workers including practicing pediatricians should encourage these “deviant” behaviors of the mothers amidst poor habits and customs which enable them to outperform their neighbors with whom they share the same resources.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by University Grant Commission (Junior research fellowship) and CSR cell of Transpek - Silox Industries Private Limited, Vadodara, Gujarat, India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was not possible without the active cooperation of the community mothers and caregivers along with their children in the process of data collection. We are thankful to our entire research team Ms. Rujuta Desai, Ms. Tanya Khanna, and Ms. Madhusree Banerjee for their constant support and cooperation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghosh S, Shah D. Nutritional problems in urban slum children. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:682–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramji S. Impact of infant & young child feeding & caring practices on nutritional status & health. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:624–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sreedhara MS, Banapurmath CR. A study of nutritional status of infants in relation to their complementary feeding practices. Curr Pediatr Res. 2013;18:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sethi V, Kashyap S, Seth V, Agarwal S. Encouraging appropriate infant feeding practices in slums: A positive deviance approach. Pak J Nutr. 2003;2:164–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schooley J, Morales L. Learning from the community to improve maternal-child health and nutrition: The positive deviance/Hearth approach. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52:376–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeitlin M. Nutritional resilience in a hostile environment: Positive deviance in child nutrition. Nutr Rev. 1991;49:259–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1991.tb07417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary Diversity. FAO. 2010. [Last accessed on 2017 Feb 02]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i1983e.pdf .

- 8.Mustaphi P. Addressing Malnutrition through Surveillance and Innovative Community Based Strategy: UNICEF Knowledge Community on Children in India. 2005:16–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shekar M, Habicht JP, Latham MC. Use of positive-negative deviant analyses to improve programme targeting and services: Example from the Tamil Nadu integrated nutrition project. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:707–13. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanani S, Popat K. Growing normally in an urban environment: Positive deviance among slum children of Vadodara, India. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:606–11. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nambiar VS, Desai R, Dhaduk JJ. Iron status of women of reproductive age living in pearl millet consuming areas of Banaskantha, Gujarat. Indian J Community Health. 2015;27(Suppl):S1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nambiar VS, Bhadalkar K, Daxini M. Drumstick leaves as source of Vitamin A in ICDS-SFP. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:383–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02723611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imran M, Subramanian M, Subrahmanyam G, Seeri J, Pradeep C, Jayan M. Positive deviance approach and supplementary nutrition under ICDS scheme on improvement of nutritional status of 2–6 year children in rural Bangalore. Natl J Community Med. 2014;5:109–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hidayat S. The Influence of Positive Deviance Approach on Nutrition (POS GIZI) Outcomes in Children Under 5 Years (CU-5) in Aceh Besar District, Aceh Province, Indonesia. 45th International Course in Health Development. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sethi V, Kashyap S, Aggarwal S, Pandey RM, Kondal D. Positive deviance determinants in young infants in rural Uttar Pradesh. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:594–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saha C, Chowdhury AR, Nambiar VS. Effect of personalized counseling as a tool for behaviour change communication for improving the nutritional status and IYCF practices of children (0-5 years) in under 5 clinic and day care centre, South 24 Parganas, West Bengal. Int J Food Nutr Sci. 2015;4:86–96. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nambiar VS, Roy K, Patel N, Saha C. Vitamin A deficiency and anemia: Alarming public health problems among the tribal Rathwa adolescents of Chhota Udaipur, Gujarat, Western India: A cross-sectional study. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2015;4:1504–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai RK, Nambiar VS. Coordinated school health approach in Indian schools may prevent the occurrence of dual burden of malnutrition among school children. J Community Nutr Health. 2015;4:26–33. [Google Scholar]