Abstract

Introduction:

Till 2016, India was the second largest consumer of tobacco in the world, second only to China. However, in June 2017, the factsheet release of Global Adult Tobacco Survey-2 showed a 6% point decline in the prevalence of tobacco use among adults (>15 years) in the country.

Materials and Methods:

This is a form of ecological study where trends in aggregate prevalence of tobacco use at country level (using secondary data) were studied in relation to corresponding policy actions over a period of two decades.

Results:

The results have shown that initial policy actions since the cigarettes act of 1975 till prevention of food adulteration Amendment act of 1995 were largely targeting cigarettes, and so smoking prevalence among men was constantly declining. On the other hand, smokeless tobacco use was increasing among both men and women and reached a peak in 2009–2010. After that, the government took strict policy actions including Food Safety and Standards Authority of India Gutka ban in 2011. There were other persistent efforts, which are discussed in this paper. As a result, a transition has occurred in relation to tobacco epidemic in India.

Conclusion:

The paper has been concluded with a note that there is no room for complacence and we have a noncommunicable disease action goal to further decline the prevalence of tobacco use in the country to <24.22% by the year 2025.

Keywords: Global adult tobacco survey, global adult tobacco survey-2, smokeless tobacco, smokeless tobacco, smoking, tobacco use

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use is a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality worldwide. Tobacco use leads to more than 7.2 million premature deaths globally each year with the majority of these deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries.[1] In India, 28.6% of adults aged >15 years use tobacco in any form, which is 6% points lower than the prevalence of tobacco use in 2009–2010.[2] Lopez et al. in 1994 proposed a four-stage model for cigarette epidemic in developed countries.[3] The four-stage model accounts for the trends and patterns of smoking over a period of decades and centuries. In Stage 1, smoking rates are low for both men and women, but cigarettes are increasing in popularity among men. In Stage 2, countries experience a sharp increase in the prevalence of smoking among men, while women gradually begin smoking as well. In Stage 3, men's rates of smoking have peaked and are starting to decline, and women's smoking also begins to decrease, but at a much slower rate. In Stage 4, the decline in women's and men's smoking rates continue.[3] The proposed model was similar to any curve of the epidemic where there is an initial rise, the peak, and then decline. The objective of this paper is to look for trends in the prevalence of tobacco use (smoking and smokeless) in India by men and women over a period of two decades, that is, from 1995 to 2017, and how such trends relate to the corresponding actions taken by policymakers over similar time frame.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a form of ecological study where trends in aggregate prevalence of tobacco use at country level (using secondary data) were studied in relation to corresponding policy actions over a period of two decades. The prevalence of tobacco use (smoking and smokeless) by men and women in India during different time frames was taken from different data sources. Thus, the paper is a secondary data analysis. The tobacco use prevalence data during 1995–1996 was taken from 52nd round of National Sample Survey Organization (52nd round). The tobacco use prevalence data during 1998–1999 were taken from the National Family Health Survey-2 (NFHS-2). The tobacco use prevalence data during 2009–2010 was taken from Global Adult Tobacco Survey-I (GATS-1) and during 2016–2017 was taken from GATS-2. The corresponding surveys were all nationally representative surveys of all the states and union territories of India. The line graphs were created using MS Excel sheet. The patterns emerging out of these graphs were then analyzed in relation to various policy actions taken from time to time.

RESULTS

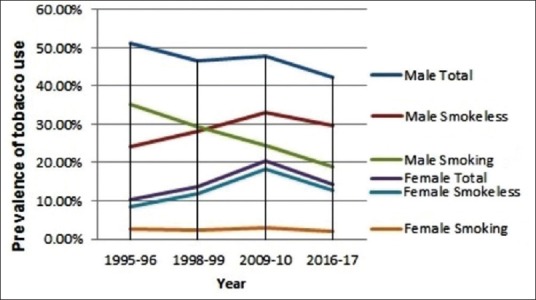

Figure 1 shows that there was a high prevalence of cigarette smoking among men in 1995–1996, with more than one-third of men (35.3%) indulged in smoking. This came down to 29.3% of men smoking cigarettes in 1998–1999, and further came down to 24.3% of men smoking cigarettes in 2009–2010 [Figure 1]. The first GATS showed a high prevalence of smokeless tobacco (SLT) use among both men and women [Figure 1]. Before that in 1998–1999, NFHS-2 also showed a high prevalence of SLT use among both men and women. The prevalence of SLT use was almost equal to the smoking prevalence among men in 1998–1999. The prevalence of SLT use among women was also high in 1998–1999 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Trends in the prevalence of tobacco use (smoking and smokeless) in India by men and women over a period of two decades, that is, from 1995 to 2017. Sources of data: 1995-96 (NSSO 52nd round); 1998-99 (NFHS 2); 2009-10 (GATS 1); 2016-17 (GATS 2)

Figure 1 further shows that the prevalence of tobacco use (total, smoking, and smokeless) among both men and women has decreased since 2009–2010. The prevalence of total tobacco use in any form, among men, has declined from 47.9% in 2009–2010 to 42.4% in 2016–2017. There is also a sharp decline in total tobacco use prevalence and SLT use, among women, since 2009–2010 [Figure 1]. The prevalence of total tobacco use in any form, among women, has declined from 20.3% in 2009–2010 to 14.2% in 2016–2017. The prevalence of SLT use among women has declined from 18.4% in 2009–2010 to 12.8% in 2016–2017 [Figure 1].

However, before 2009–2010, there was a sharp rise in the prevalence of SLT use among both men and women [Figure 1]. The smoking rates among women were rather constant around 2%–3% since 1995–1996 till 2016–2017, whereas the smoking rates among men were constantly on decline since 1995–1996 till 2016–2017. However, there is a decline in the prevalence of smoking among women from 2.9% in 2009–2010 to 2% in 2016–2017 [Figure 1].

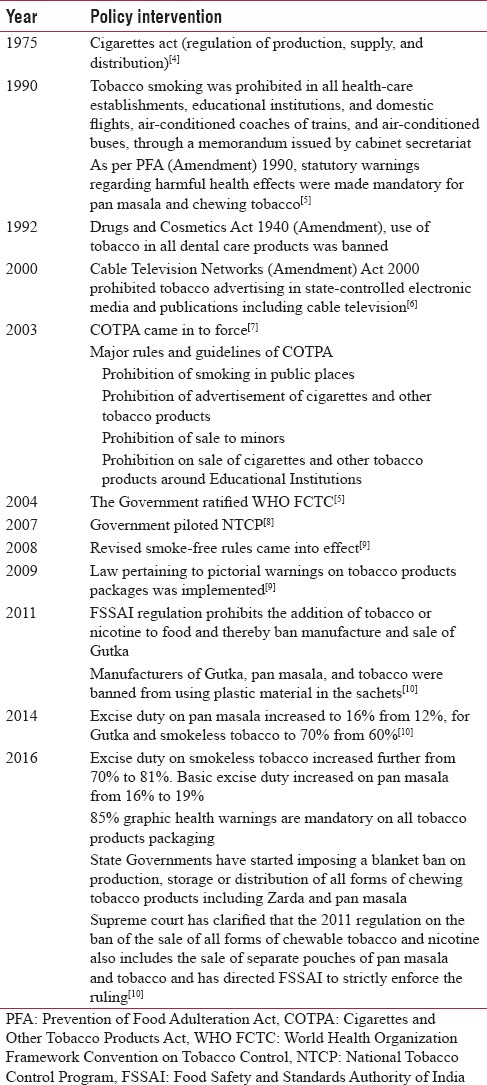

Table 1 shows a timeline of various policy interventions related to tobacco use in India, implemented since 1975 till 2017 [Table 1]. The next section discusses these interventions in detail, in relation to prevalence of tobacco use during the past two decades.

Table 1.

Timeline of various policy interventions related to tobacco use in India, from 1975 to 2016

DISCUSSION

These results are indicative of a transition in tobacco epidemic in India, from peak to declining limb along the curve of tobacco epidemic [Figure 1]. The results are also indicative of the success of tobacco control policy initiatives taken from time to time, especially after 2009–2010. However, it is a cumulative effect of all the policy initiatives taken since the formulation of Cigarettes Act in 1975,[4] because it takes persistent efforts over decades, for the results to show up.

As shown in Table 1, all the initial tobacco control legislations were targeting cigarettes, as a result cigarette smoking among men declined sharply [Figure 1]. After declining smoking rates among men, the tobacco industry started targeting women by projecting cigarette smoking among women as being fashionable, modern, independent, and empowered.[11] The industry envisaged huge potential in this naïve market segment, and thus, the industry adopted the strategy of products specifications according to market segmentation.[11] As a result, there was an increased prevalence of tobacco use among females/women during this period (1995–1996 and 2009–2010). The SLT use among females is comparatively acceptable in Indian society, whereas cigarette smoking among females has always been a taboo. It has always been perceived that “only bad girls smoke.”[12] Therefore, SLT use among females increased sharply, whereas smoking among females was rather constant [Figure 1].

The major concern for tobacco control activists in the 21st century was rising SLT use among both men and women [Figure 1]. However, there was an intention to quit among tobacco users. GATS India 2009–2010 showed that about 38% smokers and 35% SLT users made an attempt to quit within 1 year before the survey.[13]

To address these concerns in India, the central government started contemplating some comprehensive tobacco control legislation. Meanwhile, many state-level governments in India moved ahead with state laws imposing different types of tobacco control legislation.

There was a major barrier to include all tobacco products under single legislation; as the different tobacco products fall under the separate legislative purview of the central and state governments, in the federal structure. The cigarettes were in the concurrent list and the central governments could make a legislation regarding them which was already there in the form of “Cigarettes Act” of 1975.[14] The tobacco products other than cigarettes fall under state list and thus the central government needed resolutions from at least two state legislatures to make a law covering other tobacco products. Subsequently, the states of Goa, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab passed resolutions in their state legislatures and thus authorized the central parliament to formulate comprehensive tobacco control legislation.[14]

In February 2001, then Prime Minister Vajpayee's Union Cabinet introduced the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply, and Distribution) Bill, a multifaceted antitobacco legislation, to replace the Cigarettes Act of 1975.[15] This bill covered most tobacco products including not only cigarettes but also bidis, cigars, cheroots, pipe tobacco, hookah tobacco, chewing tobacco, gutka, and pan masala.[7]

The crossroads for SLT was Environment Ministry's Plastic Waste (Management and Handling) Rules, 2011, that prohibited the use of plastic materials in sachets for storing, packing, or selling gutka, tobacco, and pan masala. The rules came into effect from February 2011. This increased the price of gutka and pan masala for consumers. Yet, not all manufacturers followed this ban and many of them were still selling in plastic packaging.[9] Furthermore, in the same year, Food Safety and Standards (Prohibition and Restriction on sales), regulation 2011, explicitly stated that “Product not to contain any substance which may be injurious to health: Tobacco and nicotine shall not be used as ingredients in any food products.”[9] This was a central legislation in effect from August 5, 2011, and needed to be implemented through state governments. State governments have started imposing a blanket ban on production, storage, or distribution of all forms of chewing tobacco products including zarda and pan masala. Supreme court has clarified that the 2011 regulation on the ban of the sale of all forms of chewable tobacco and nicotine also includes the sale of separate pouches of pan masala and tobacco and has directed Food Safety and Standards Authority of India to strictly enforce the ruling.[10]

The government also increased the size of pictorial warnings on tobacco products to 85% of the packet size from the previous 40%.[10] Furthermore, the excise duty on SLT increased further from 70% to 81%. Basic excise duty increased on pan masala from 16% to 19%.[10] Although the GATS-2 survey was also conducted during the same year (August 2016–February 2017), and therefore, these policy interventions taken during 2016 itself might NOT have impacted the prevalence of tobacco use during this period. These policy interventions may have long-term effects and the results will be reflected in the next survey. However, still GATS-2 has showed that India has made a mark in the history of global tobacco control.

CONCLUSION

Although India has reached on the descending limb of tobacco epidemic, there is no room for complacence. High SLT use prevalence among women is a major concern which should be dealt with in a gender-sensitive context. There is a global target of 30% relative reduction in the prevalence of current tobacco use in persons aged 15 years and above by 2025 in the noncommunicable disease Action Plan. For India, it will be 30% relative reduction in GATS-1 tobacco use prevalence, which comes out to be 24.22% or less. The prevalence of tobacco use in GATS-2 that is, 2016–2017 is 28.6%. Thus, by 2025, it is possible to lower it down further to <24.22%. It shows we have set specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound objectives for our tobacco control efforts. At the same time, it is important to take care of all the stakeholders, by strengthening “alternative livelihoods” component of our tobacco control policies.

Limitation

The limitation of this study is that it used prevalence rates for tobacco use in different years from different surveys which had different sampling methodologies and used different criteria for the definition of tobacco use.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1659–724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GATS – 2 (Global Adult Tobacco Survey – 2) Factsheet. India 2016-17. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India. World Health Organisation; Tata Institute of Social Sciences. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 14]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/india/mediacentre/events/2017/gats2_india.pdf?ua=1 .

- 3.Lopez AD, Collishaw NE, Piha T. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob Control. 1994;3:242. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of India. The Cigarettes Act (Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution) 1975. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 15]. Available from: http://www.indianrailways.gov.in/railwayboard/uploads/directorate/security/rpf/Files/law/BareActs/cigaretts_act1975.html .

- 5.Kaur J, Jain DC. Tobacco control policies in India: Implementation and challenges. Indian J Public Health. 2011;55:220–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.89941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Cable Television Networks Act, 1995. Government of India. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. [Last accessed on 2017 Jun 16]. Available from: http://www.mib.nic.in/information&b/media/acts&rules/1995.htm .

- 7.The Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and regulation of Trade and Commerce, production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003; An Act enacted by the Parliament of Republic of India by Notification in the Official Gazette. (Act 32 of 2003) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Government of India. National Tobacco Control Programme. 2007-08. [Last accessed on 2018 Jun 4]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in .

- 9.Arora M, Madhu R. Banning smokeless tobacco in India: Policy analysis. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:336–41. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.107724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A Report Compiled by Euromonitor International for World Health Organization. New Delhi: Euromonitor International; 2016. Euromonitor Consulting. Smokeless Tobacco in India. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amos A, Haglund M. From social taboo to “torch of freedom”: The marketing of cigarettes to women. Tob Control. 2000;9:3–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruhil R. Gender and tobacco use in India. In: Pratap P, editor. Socioeconomic Empowerment. New Delhi: Stadium Press; 2018. pp. 224–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruhil R. Correlates of the use of different tobacco cessation methods by smokers and smokeless tobacco users according to their socio-demographic characteristics: Global adult tobacco survey (GATS) India 2009-10. Indian J Community Med. 2016;41:190–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.183598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy KS, Gupta PC. Report on Tobacco Control in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimkhada R, Peabody JW. Tobacco control in India. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:48–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]