Abstract

Background:

Community participation is one of the core principles of primary healthcare. The village health nutrition and sanitation committee (VHNSC), one of the elements in implementation of the National Health Mission (NHM), is an example of community participation. There are not many studies conducted to assess the actual participation of VHNSC in health-care delivery at the village level.

Objective:

The objective of the study is to develop a VHNSC Maturity Index (VMI) and pilot it to assess the institutional maturity of VHNSC.

Materials and Methods:

This community-based, cross-sectional study was conducted in 83 villages under four Primary Health Centres (PHCs) of the Wardha Community Development block. VMI was developed, Through several discussion sessions with VHNSC members and staff of the DCM; observations of VHND; attending VHNSC monthly meetings; the VMI was finalized after piloting it in all the four PHC areas.

Results:

All the 83 VHNSCs were constituted as per norms led down under NHM. Forty-eight (57.8%) VHNSCs had developed an annual Village Health Action Plan, 72 (86.7%) VHNSCs had ≥4 meetings held in the past 6 months, and ≥70% attendance in the past 6 months was observed in 40 (48.2%) VHNSCs. A majority of 82 (98.8%) VHNSCs helped in organizing the village health and nutrition day, 59 (71.1%) VHNSCs monitored the implementation of national health programs. The entire untied fund received in the previous year was utilized by 68 (81.9%) VHNSCs.

Conclusion:

The study shows that VMI can be used for continuous monitoring and assessment tool for VHNSC to evaluate and plan different health activities.

Keywords: Community participation, decentralization, health committee, National Health Mission, village health nutrition and sanitation committee

INTRODUCTION

Community participation is one of the core principles of primary healthcare. The World Health Organization suggested that the development should be more people-centered and should more directly promote people's participation.[1]

The government of India under the National Health Mission (NHM) (earlier National Rural Health Mission [NRHM]) stated to involve local communities in assessing progress on the health action plans. Public participation in monitoring is mediated through representatives of community-based organizations. One of the key elements in the implementation of the NHM is the Village Health Nutrition and Sanitation Committee (VHNSC). VHNSCs are formed at revenue village level and act as subcommittee of Gram Panchayat. They are particularly envisaged as being central to the “local level community health action” under NHM, which would develop to support the process of decentralized health planning. Thus, VHNSCs are expected to act as leadership platforms for improving awareness and access of community for health services, support the healthcare providers, develop village health plans specific to the local needs, and serve as a mechanism to promote community action for health.[2] In Maharashtra, a total of 39,955 VHNSC have been established in revenue villages.[3]

Community participation is also practiced in others countries with positive outcomes in terms of health-care services. The Village Health Committees and Health Centre Management Committees were set up for Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and Community Health Centres under Communitization in Nagaland,[4,5] which showed improvement in attendance of health staff, their behavior with patients, attendance of patients, and drug availability in public health facilities. Local committees for health administration were set up in Peru[6] (33% representation of elected members from the community) and facilities with these committees reported better user satisfaction and better access to the poor.

One of the objectives of VHNSC is to provide an institutional mechanism for planning and monitoring of health services. The process of empowering of VHNSCs for delivering decentralized health-care needs to be adequately studied. There are neither many studies conducted to assess the actual participation of VHNSC in health-care delivery at the village level nor a continuous monitoring and assessment tool for VHNSC to evaluate and plan different health activities. Therefore, the present research study was conducted to assess the functioning and maturity of the VHNSC in the study area by developing a VHNSC Maturity Index (VMI) and piloting it to assess the institutional maturity of VHNSC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted in 83 villages under four PHC areas – Waifad, Anji, Kharangana gode, and Talegaon lying in the field practice area of the Department of Community Medicine (DCM) of the Medical College in a district of Maharashtra. The study population comprised of members of all 83 VHNSCs under the four selected PHC and the health-care providers in the respective PHC. The maturity index developed for VHNSC was applied to 83 VHNSCs by the researcher and data collected.

Developing village health nutrition and sanitation committee maturity index

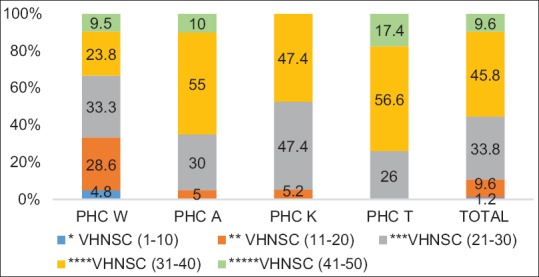

The Institutional Maturity Index (IMI) for the VHNSC was developed to access the effectiveness of VHNSCs and was named as VMI. Through several discussion sessions with VHNSC members, community-based organizations, Gram Panchayat members, staff of the PHC, and staff of the DCM, the VMI was finalized after piloting it in all the four PHC areas. The draft VMI was developed and was piloted in all the four PHCs (three randomly selected VHNSCs from each PHC). It was observed that all the 10 activity/characteristics need to be allotted equal weightage for the assessment of VHNSC. Further to be precise in assessing each activity/characteristic, five observations under each activity/characteristics were confirmed. One point each was allotted if a particular observation was fulfilled by the VHNSCs and no point was given if the particular observation was not fulfilled. According to the VMI, each VHNSC was scored on a “maturity” scale of 1–50. The pilot-tested VMI was then applied to 83 VHNSCs under four PHCs. Each VHNSC was then categorized according to VMI scores as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Maturity and categorization of Village Health Nutrition and Sanitation Committees as per Village Health Nutrition and Sanitation Committee Maturity Index scores, (figures in parenthesis indicates Village Health Nutrition and Sanitation Committee Maturity Index Scores)

It was a cross-sectional study where the quantitative method was used to study the role of VHNSCs in decentralized healthcare delivery in the study area. VMI was developed, Through several discussion sessions with VHNSC members and staff of the DCM; observations of VHND; attending VHNSC monthly meetings; the VMI was finalized after piloting it in all the four PHC areas. The VMI was then used to assess the institutional maturity of all the 83 VHNSCs in the study area.

RESULTS

Developing and piloting of village health nutrition and sanitation committee maturity index

The VMI was developed considering NHM guidelines for VHNSC. The IMI, which was developed for Village Coordination Committee during the Community Led Initiatives for Child Survival project implemented by DCM, was used as a reference.[7,8] VMI thus included the following: constitution of VHNSC, village health planning, VHNSC monthly meeting, facilitating service delivery and service providers in the village, organize local collective action (in last 6 months), community monitoring of health-care facilities, VHNSC coordination with others, monitoring and facilitating access to essential public services, record maintenance, and utilization of untied fund.

Assessment of village health nutrition and sanitation committees by village health nutrition and sanitation committee maturity index

The VMI was used to assess VHNSCs with respect to their activity and maturity.

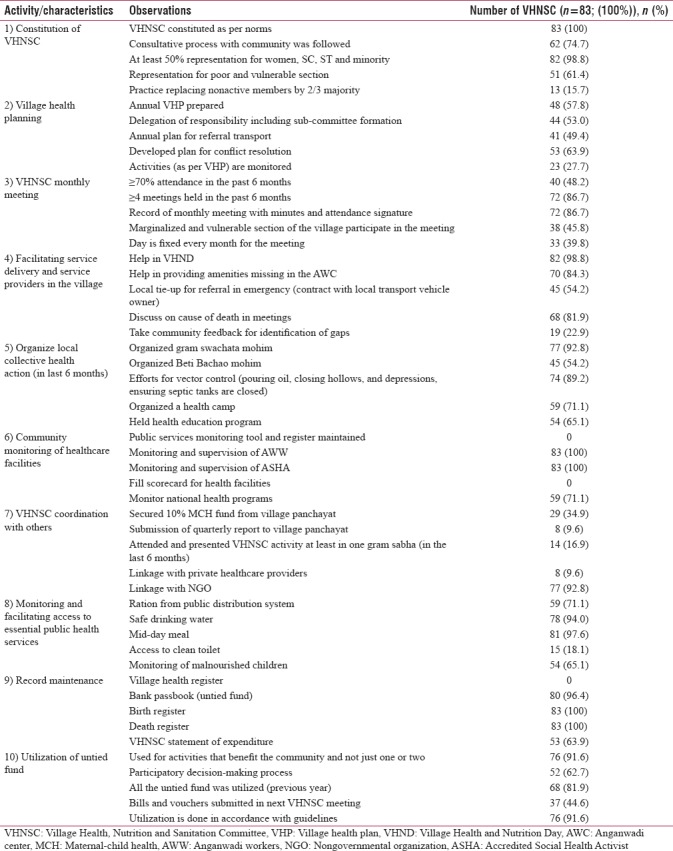

Activity of VHNSCs [Table 1]: It was observed that all the VHNSCs were constituted as per norms led down by NHM and more than half had developed an annual village health plan. It was further observed that most of the VHNSCs had more than or equal to four meetings held in the past 6 months and majority also helped in organizing village health and nutrition day and providing amenities missing in the AWC. Around half of the VHNSCs had tie up with local vehicle owner for emergency transport.

Table 1.

Activity of Village Health, Nutrition and Sanitation Committees as assessed by Village Health, Nutrition and Sanitation Committee Maturity Index

All VHNSCs did monitoring and supervision of AWW and ASHA while most VHNSCs monitored implementation of national health programs. Coordination of VHNSC with other organizations was assessed and showed that the majority of VHNSCs were monitored and facilitated access to essential public services such as ration from public distribution system, safe drinking water, mid-day meal, and monitoring of malnourished children.

However, only few VHNSCs practiced replacing the nonactive members in the committee. None of the VHNSCs filled scorecard for health facilities, while only few worked on access to clean toilet.

The maintenance of record and utilization of untied fund was assessed. All VHNSCs maintained birth and death register, bank passbook. Most of the VHNSCs had participatory decision-making process for utilization of fund.

Maturity of VHNSCs [Figure 1]: Based on the VMI scores, each VHNSC was then categorized as one star (poor performing) to five stars (best performing).

According to the average VMI score of all VHNSCs in a PHC, the overall functioning of VHNSCs in PHC Talegaon (36) and PHC Anji (35) was better than PHC Kharangana gode (29) and PHC Waifad (27). Figure 1 shows PHC-wise maturity of all 83 VHNSCs according to VMI scale from one to five star categories. Only one VHNSC from PHC Waifad was in the one-star category (VMI score of 1–10). Eight (9.6%) of the VHNSCs were in the five-star category (VMI score of 41–50). Most of the VHNSCs remained either in the three-star category (VMI score of 21–30) or four-star category (VMI score of 31–40) during the assessment. Most of the VHNSCs from PHC Talegaon and PHC Anji remained in the four-star category.

DISCUSSION

Local communities having a role in tackling their health problems is not a new concept. In the 1950s and 1960s, urban and rural community development initiatives sought to involve local people in management and decision-making. However, with the advancement in technologies and centralization of health services, more of these services became responsibility of health-care workers. The Alma-Ata conference recognized the need to halt this trend if effective health services are to be extended to all.[9]

VHNSC is a step taken to involve local communities in addressing social determinants of health in a participatory manner. In the present study, an attempt has been made to develop a tool to assess the maturity of VHNSCs according to the functions specified by NRHM.

Almost all (98.8%) VHNSC under the present study were constituted as per norms led down by NRHM and this finding is similar to the study conducted by Srivastava et al.[10] in Jharkhand and Orissa. However, the study by Singh and Purohit[11] in the Northwestern state of India indicated many problems and gaps in composition, formation, and functioning of VHSC. Apart from the constitution of committee according to guidelines, the present study also included activities such as following of consultative process with the community during constitution of the committee and practicing replacement of nonactive member by two-third majority which would promote maximum participation and effective functioning of VHNSCs.

Village health planning is one of the functions of VHNSC, and the present study showed that annual village health plan was prepared in almost half of the VHNSCs, while some studies reported as 74% of VHSNCs in Chhattisgarh and 83% in Odisha, while only 8% in Jharkhand had a VHP.[10,12]

The study showed that though the meetings were held regularly, more than 70% attendance was seen in 40 (48.2%). Srivastava et al.,[10] in her study, found that VHNSCs in the Eastern part of India struggled in arranging regular meetings with full attendance, whereas Semwal et al.,[13] in his study, reported that among all 18 VHNSCs, meetings were organized irregularly. Regarding the members attending meetings, Pandey and Singh[14] reported that around 61% of ASHAs, 53% of the community members, and 41% of PRI members attended the VHSNC meetings; however, the present study also looked for participation of marginalized and vulnerable section which was only in 38 (45.8%) VHNSCs.

The present study showed that almost all VHNSCs utilized untied fund for previous year, and similar observation were made by Manjit Das et al.[15] in rural Assam, where a majority of (67.93%) VHSNCs utilized more than 90% of the funds allotted to them.

VHNSCs are expected to address issues related to sanitation. A nongovernmental organization led community participatory approach in Bangladesh showed how a community can play a remarkable role in expanding sanitation coverage. It showed that sanitary latrine use was significantly higher (P < 0.01) among household involved in program than the comparable nonprogram target households.[16] The present study also showed that more than half (65.1%) of the VHNSCs organized health education programs to increase awareness on sanitation. Similarly, a community participatory approach in Nepal indicated that the community people are prepared to spend as much as 75% of the building cost of constructing sanitary toilets when they were convinced that health will improve as a result.[17]

Involvement of community in the planning process can lead to effective utilization of resources. Community-based monitoring and planning in Maharashtra indicated that involvement of community in the process led to more appropriate use of RKS funds based on the priorities of the community.[18] While in the present study, the united fund in previous year was utilized by 68 (81.9%) VHNSCs and Srivastava et al. reported that the utilization was by 57% in Jharkhand.[10]

Communities can be effectively involved to promote awareness of health services, plan community needs assessment, carry out village level health activities and foster trust between the community and the health services. The Foundation for Research in Health Systems conducted in 2000 an 18-month pilot project in one block of Mysore district showed that community participation led to improvements in health outcomes including in institutional deliveries, treatment seeking for reproductive tract infections, and weighing of babies at birth.[19] There are several studies indicating positive outcomes in health when the local communities were involved in the process. In Bolivia, women's organizations in the communities were engaged in the process of “auto-diagnosis” under Warmi project[20] which showed an impressive decrease in perinatal mortality from 117 to 43.8 per 1000 births. Representation for women and marginalized sections in Health Watch Committees, Bangladesh[21] had increased the awareness about health services and attendance in health facilities and of health providers.

Thus, community participation has a great potential to address health issues; however, it requires capacity building and hand holding. The present study was a community-based study, and the VMI was developed in a participatory manner thus making it easy to use, more acceptable by the VHNSC members, which can be used for continuous quality monitoring of the functioning of VHNSC. Further, the VMI covers most of social determinants of health which the VHNSC is expected to address.

However, the findings of the study should be interpreted considering the limitations that the study was conducted in PHCs, selected for feasibility, in the field practice area of the DCM which has already been working on community mobilization, and hence, these VHNSCs may not be a representative of other VHNSCs of rural India. This study also does not explore the detail reasons for low performance of VHNSC on VMI scale.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

VHNSC has a vital role in decentralized health planning and monitoring. NHM envisaged VHNSC to function adequately with involvement of community members and promote people's participation in the planning process. However, there should be a tool which facilitates in planning, implementation according to village specific health plan, and community monitoring of health services at the village level. The VMI developed in this study is such a tool which could be easily administered to identify the areas requiring improvement in VHSNCs and help in proper delivery of healthcare services covering many of the social determinants of health.

Using the VMI, further studies could be carried out to know the exact barriers in functioning of VHNSC which will help us to develop a strong institutional mechanism for planning and monitoring of health services.

In the present study, an attempt has been made to develop a tool to assess the maturity of VHNSCs and thus can be concluded that the VMI can be used as continuous monitoring and assessment tool for VHNSC to evaluate and plan different health activities. However, the VMI requires further validation by many such studies in different parts of the country.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research work was a part of larger ICMR project conducted for piloting community-owned health management information system.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organisation. The World Health Report: Health Systems: Principled Integrated Care. Ch. 7. [Last accessed on 2018 Apr 08]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2003/chapter7!en/index1.html .

- 2.Government of India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Rural Health Mission. Guidelines for Village Health Nutrition and Sanitation Committees (VHNSC) [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/communitisation/vhnsc/orderguidelines/guidelinesforcommunity processes2014 .

- 3.Government of Maharashtra. State Health Society. Maharashtra: National Rural Health Mission, Village Health Nutrition Water Supply and Sanitation Committee. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.nrhm.maharashtra.gov.in/vhswsc.htm .

- 4.Bahl A. Communitisation of Grassroot Health Services. Nagaland: Policy Reforms Options Database Reference Number: 128. 2005. [Last accessed on 2017 Jan 02]. Available from: http://www.hsprodindia.nic.in/ret.asp .

- 5.Presentation on Communitisation. Improving Public Services: The Nagaland Experience. Government of Nagaland. 2013. [Last accessed on 2017 Jan 02]. Available from: http://www.gad.bih.nic.in/Gallery/Dr-Toko-Presentation-on-Communitization.pdf .

- 6.Iwami M, Petchey R. A CLAS act? Community-based organizations, health service decentralization and primary care development in Peru. Local Committees for Health Administration. J Public Health Med. 2002;24:246–51. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/24.4.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutta SS, Garg BS. To Assess the Effectiveness of VCC in Decentralized Health Care Delivery in Rural Area. Nasik: MUHS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Community Medicine. Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences Sewagram. Community Led Initiatives for Child Survival Program (CLICS) Annual Report. 2014:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oakley P, Kahssay HM. Community Involvement in Health Development: A Review of the Concept and Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srivastava A, Gope R, Nair N, Rath S, Rath S, Sinha R, et al. Are village health sanitation and nutrition committees fulfilling their roles for decentralised health planning and action? A mixed methods study from rural Eastern India. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:59. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2699-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh R, Purohit B. Limitations in the functioning of village health and sanitation committees in a north western state in India. Int J Med Public Health. 2012;2:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committees (VHSNCs) An Assessment State Health Resource Centre. Raipur, Chhattisgarh: Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committees; 2013. pp. 31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semwal V, Jha SK, Rawat CM, Kumar S, Kaur A. Assessment of village health sanitation and nutrition committee under NRHM in Nainital district of Uttarakhand. Indian J Community Health. 2013;25:472–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandey A, Singh V. Tied, Untied Fund? Assessment of Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committee, Involvement in Utilization of Untied Fund in Rajasthan. 2012. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 24]. pp. 1–4. Available from: http://www.chsj.org/uploads .

- 15.Das M, Ojah J, Baruah R. The functioning of the village health sanitation and nutrition committee. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2016;5:2052–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadi A. A participatory approach to sanitation: Experience of Bangladeshi NGOs. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:332–7. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upadhya DP. Community participation in improving environmental situation – A case study of Panchkhal. Part II. JOICFP Rev. 1983;6:25–31. Spring. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maharashtra State Health Department and SATHI-CEHAT. Community Based Monitoring and Planning of Health Services in Maharashtra Supported by NRHM. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.cbmpmaharashtra.org .

- 19.Murthy N, Vasan A. Community Involvement in Reproductive Health: Findings from an Operations Research Project in Karnataka, India. Ahmedabad: Foundation for Research in Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Rourke K, Howard-Grabman L, Seoane G. Impact of community organization of women on perinatal outcomes in rural Bolivia. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1998;3:9–14. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891998000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahmud S. Spaces for participation in health systems in rural Bangladesh: The experience of stakeholder community groups. In: Cornwall A, Coelho VS, editors. Spaces for Change? The Politics of Citizen Participation in New Democratic Arenas. 1st ed. London and New York: Zed Books; 2006. pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]